ABSTRACT

Premalignant and malignant lesions of the anal margin are rare. Understanding anal anatomy and performing a biopsy of any suspicious lesions are essential in avoiding a delay in diagnosis and appropriately treating these tumors. Wide local excision continues to remain the treatment of choice for many of these lesions. Combined multimodality treatment has come to play an important role in managing patient with more advanced or metastatic disease.

Keywords: Anus neoplasms, Bowen's disease, Paget's disease, squamous cell cancer

Perianal neoplasms are a rare entity. They include basal cell cancer, extramammary Paget's disease, Bowen's disease, malignant melanoma, and squamous cell cancer. Together they account for 3 to 4% of all anorectal neoplasms.1,2 Often, lesions in this area are misdiagnosed and consequently treatment delayed. Considerable progress has been made in the treatment of premalignant and malignant lesions over the past several decades. These advances have resulted in decreased treatment-related morbidity and significant improvement in mortality. The diagnosis and management of perianal premalignant neoplasms, Bowen's and Paget's diseases, and squamous cell carcinoma of the anal margin are described.

ANATOMY OF THE ANUS

The anatomy of the anal canal is a determining factor in the management of patients with specific types of perianal and anal lesions. Traditionally, the “surgical” anal canal has been defined as extending from the anorectal ring (upper portion of the levator complex) to the anal verge. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines the anal canal as extending from the upper to the lower border of the internal anal sphincter. Based upon its epithelial lining, the anal canal can be further divided into three zones: the colorectal zone, which is proximally lined by columnar epithelium; the anal transitional zone (ATZ), which extends 1 cm proximal from the dentate line and is lined by a mixture of epithelial variants; and the squamous zone, which extends from the dentate line to the anal verge. The ATZ with its mixed epithelial lining is considered important in maintaining fecal continence. The anal verge is defined as the point where the squamous epithelium of the anal canal meets the hair-bearing perianal skin. The anal margin refers to the perianal skin extending about 5 cm from the anal verge.3,4 The focus of this review is on tumors limited to the anal margin.

The pattern of lymphatic drainage of the anal canal plays a crucial role in tumor spread. Drainage from the colorectal zone and the ATZ is cephalad to the inferior mesenteric nodes through the superior rectal lymphatics but may also occur to the inguinal-femoral lymph nodes through the middle and inferior rectal lymphatics. Lymphatic drainage between the dentate line and anal verge is predominately to the inguinal-femoral lymph nodes. Secondary drainage can occur through the inferior rectal lymphatics to the ischioanal nodes and internal iliac nodes. Drainage from the perianal skin is entirely to the inguinal nodes.3

PREMALIGNANT LESIONS

Bowen's disease and Paget's disease are the two main premalignant lesions of the anal margin. These lesions are rare and often misdiagnosed because of the nonspecific nature of symptoms.

Bowen's Disease

Bowen's disease, first described by John T. Bowen5 in 1912, is an intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma (carcinoma in situ) that occurs most frequently on the face, hands, and trunk, with the perianal location being the least common.6 Perianal Bowen's disease is considered a rare, slow-growing, premalignant lesion and probably represents severe anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN). It is estimated to progress to invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in 2 to 6% of cases.1,7,8,9,10

Bowen's disease, like AIN and SCC, is associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) infection types 16 and 18. HPV 16 has been found in 60 to 80% of patients with Bowen's disease.3 It has been observed that HPV-associated malignancies, including anal in situ cancers, occur more frequently in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Frisch et al examined invasive and in situ HPV-associated cancers among patients with HIV from 5 years prior to the date of AIDS onset to 5 years after onset. The authors found an increased risk of in situ and invasive anogenital cancers in the HIV/AIDS population when compared with the expected number of cancers. When analyzing the 10-year span of AIDS onset, the relative risk (RR) for in situ anal cancers increased significantly from 5 years prior to 5 years after the onset of AIDS. However, the RR for invasive anal cancer changed little over this span, suggesting that immune status did not seem to have as important a role in progression from in situ to invasive malignancy.11

Bowen's disease has the highest incidence during the sixth and seventh decades of life. Common symptoms include itching, burning, and occasionally bleeding.1,7,10 Because of the nonspecific nature of complaints, the diagnosis is often made incidentally with pathology obtained for another anorectal procedure. In a study of 33 patients with Bowen's disease by the Cleveland Clinic, 61% of patients presented with symptoms whereas 39% of individuals were found to have the condition after undergoing a hemorrhoidectomy.12

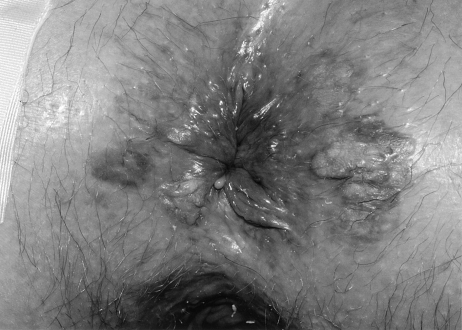

Clinically, the lesion often appears as a well-defined erythematous, scaly plaque (Fig. 1). Diagnosis is made by obtaining several full-thickness biopsy specimens from the central portion and edges of the lesion. Histologically, the lesion demonstrates epithelial hyperkeratosis, atypical epithelial cells with mitotic figures and loss of polarity, and full-thickness epidermal involvement. The characteristic finding is the Bowen cell, which appears as a large, atypical cell with a haloed, hyperchromatic nucleus. These cells are periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) negative.1,6,10

Figure 1.

Bowen's disease.

Wide local excision has been the treatment of choice in patients with Bowen's disease, despite the relatively high rate of recurrence.12,13,14 Marchesa et al retrospectively compared patients who had undergone wide local excision versus those with negative microscopic margins to conservative treatment (local excision with gross macroscopic margins and CO2 laser vaporization) and found a significantly lower recurrence rate in the wide local excision group (53.3% versus 23.1%). However, the recurrence rate in the wide local excision group was still 23.1%.14 Because of the inability to determine the extent of disease by gross inspection, frozen section analysis is needed to ensure negative margins. Mapping has been advocated as an effective way to determine the extent of disease.12 Mapping consists of performing a systematic four-quadrant biopsy of the anal canal, anal verge, and perianal skin in addition to performing biopsies of any suspicious or abnormal areas. The involved area is widely excised based on the results of the biopsies. A formal mapping procedure does not preclude recurrence.15

Often, extensive excisions are required, resulting in large wounds that may be difficult to close. Treatment for these wounds has included primary closure, healing by secondary intention, staged excision with split-thickness skin grafts, advancement rotation flaps, myocutaneous flaps, and V-Y island flaps. Flaps and skin grafts have been used primarily in the treatment of large wounds.16

Because of the need for wide local excisions with large wounds and the relative low rate of developing an invasive SCC, less aggressive treatment options have been used. These more conservative treatment regimens that have been described have included cryotherapy, argon laser therapy, photodynamic therapy, radiation, 5-fluorouracil cream, infrared coagulation, and close observation.17,18,19,20,21,22 A recent study reported good outcomes with the use of 5% 5-fluorouracil treatment in patients with extensive perianal Bowen's disease.23 Currently, wide local excision remains the treatment of choice.

Follow-up in patients for Bowen's disease remains unclear. Generally, it has been recommended that patients undergo annual physical examination, proctosigmoidoscopy, and biopsies of prior resection margins and any new lesions. If recurrent disease is found, wide local excision is again the treatment of choice. Patients should be observed for longer than 5 years because of the possibility of late recurrences.14

There has been considerable controversy over whether Bowen's disease is associated with a risk of developing internal malignancies. Initial reports indicated that there was an association; however, more recent studies have indicated that that seems not to be the case.24,25,26 In a Danish, population-based cohort study of 1147 patients, the authors did not find that patients with Bowen's disease were at increased risk for developing internal malignant neoplasms; however, they did confirm earlier reports of the higher incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancers among patients with Bowen's disease.25

Perianal Paget's Disease

In 1874, Sir James Paget first described this pathologic lesion in breast tissue. Paget's disease is an intraepithelial adenocarcinoma (adenocarcinoma in situ) thought to arise from dermal apocrine sweat glands. Extramammary Paget's disease refers to tumor in locations other than the breast where apocrine glands are found. Perianal Paget's disease was first described in 1893 by Darier and Coullillaud and represents about 20% of extramammary lesions.1,6,7 Although Paget's disease of the nipple is almost always associated with an underlying invasive tumor, perianal Paget's disease is not. There has been a much stronger correlation with an associated malignancy for Paget's disease than Bowen's disease. These underlying malignancies include apocrine or eccrine carcinoma, rectal adenocarcinoma, and anal carcinoma. The reported incidence of associated malignancies ranges from 38 to 69%.1,8,27

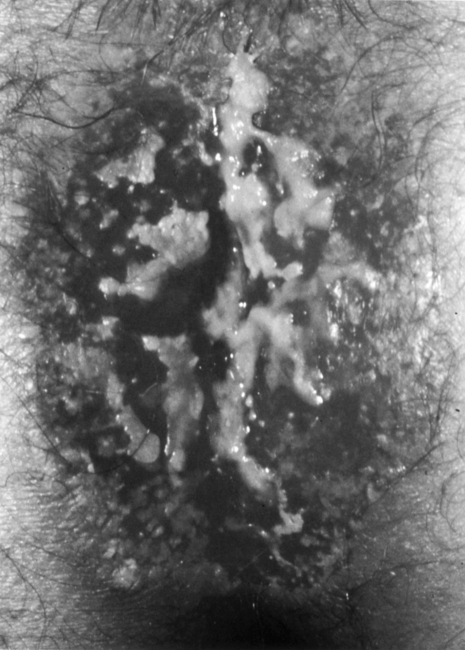

Patients with Paget's disease have an average age in their 60s, with women having a higher incidence than men.1,7 The most common symptom of Paget's disease is itching. Patients may also present with discharge, ulceration, and occasional bleeding and pain. On gross examination, the lesions appear erythematous, raised, crusty, and plaquelike (Fig. 2). Diagnosis is made by biopsy with histology revealing Paget's cells. These large, pale, vacuolated cells contain large nuclei with high mucin content, which, unlike those in Bowen's disease, can be identified by PAS stain. Hyperkeratosis, parakeratosis, and acanthosis are also frequently present.

Figure 2.

Perianal Paget's disease.

As in Bowen's disease, full-thickness biopsies of the lesion as well as mapping are generally performed.28 Treatment is dependent on the presence or absence of underlying invasive adenocarcinoma. As with Bowen's disease, wide local excision with mapping is the treatment of choice for noninvasive disease.28 Wide local excision compared with local excision has been shown to reduce the rate of recurrence and improve overall survival.29,30 McCarter et al reviewed the outcomes of 27 patients with perianal Paget's disease, most of whom were treated by wide local excision (74%). Local recurrence occurred in 37% of all patients and 30% of patients treated by wide local excision with 44% of patients having an invasive component. The overall survival and disease-free survival at 5 years were 59 and 64%, respectively, which decreased to 33 and 39%, respectively, at 10 years.29 With large defects, skin grafting or rotational flaps may need to be performed. For circumferential perianal Paget's disease, staged excision with split-thickness skin graft has been reported to have good functional outcomes.31

Unlike the situation in Bowen's disease, which has a low incidence of development to invasive carcinoma, invasive carcinoma has been reported in up to 40% of patients with untreated Paget's disease and historically carries a poor prognosis.1,29 Thus, for patients with invasive disease, aggressive therapy should be considered. In patients with invasive disease without metastasis, treatment may include an abdominoperineal resection (APR) or adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation, or both.1,29 Long-term survivors have been reported after APR in patients with invasive Paget's disease without metastasis.7 The role of chemoradiation in treatment of patients with invasive Paget's disease remains undefined.29 Patients should be observed in the long term because of the risk of late recurrence and undergo proctosigmoidoscopy and anoscopy to assess for an associated underlying malignancy.27

SQUAMOUS CELL CARCINOMA OF THE ANAL MARGIN

Squamous cell cancer of the perianal area behaves in a similar manner to tumors in other cutaneous locations. Carcinoma of the anal margin is anatomically and clinically distinct from tumors in the anal canal. It is a rare and at least fivefold less common than carcinomas of the anal canal.32 As noted previously, the perianal region or anal margin refers to a 5-cm region extending around the anal verge. It is important to differentiate between perianal and anal canal carcinoma because of their different prognoses and treatments. The literature has been somewhat confusing because of the grouping of perianal cancer with anal canal cancer.

Multiple risk factors for developing anal cancer have been studied. As with cervical cancer, infection with HPV, especially types 16 and 18, has a strong association with perianal and anal canal cancer.33 Frisch et al, in a population-based study, found that 88% of anal cancer specimens were positive for HPV infection with 73% of specimens positive for HPV type 16 infection.34 Additional risk factors with strong supporting evidence include a history of receptive anal intercourse, history of sexually transmitted diseases, more than 10 sexual partners, a history of other anogenital cancer (cervical, vulvar, or vaginal), and immunosuppression after solid-organ transplantation.2

SCC lesions are usually hard, ulcerated, and raised with rolled, everted edges (Fig. 3). Most patients present in the seventh and eighth decades of life with an approximately equal male-to-female predominance.4,32 Symptoms are nonspecific and include bleeding, pain, drainage, and pruritus. Because of the nonspecific complaints and the mistaking of the lesions as benign disease, the diagnosis if often delayed.35

Figure 3.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal margin.

Pathologically, the lesions are well differentiated and keratinized. Lesions usually grow slowly with lymphatic spread mainly to the superficial inguinal lymph nodes and much less commonly to the mesenteric or internal iliac nodes. Tumor size and lymph node involvement have been demonstrated to be important prognostic factors in patients with perianal SCCa.36,37 Metastasis to the inguinal nodes occurs in 15 to 25% of patients and is related to the size and differentiation of the primary tumor. Papillon and Chassard reported that tumors 2 to 5 cm and 5 cm or larger had 24% and 67% rates, respectively, of having nodal involvement at presentation.37 Staging of SCCa of the anal margin is performed according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and follows staging for other skin cancers.32,38

The goal of treatment of perianal disease is to cure the patient while maximally preserving anal function. Prior to the report in 1974 of treating anal canal cancers with multimodality treatment by Nigro and colleagues,39 the standard of treatment for perianal and anal canal cancers was surgical and consisted of wide local excision or APR. With the success of chemoradiation therapy for the treatment of anal canal cancer, there have been many reports of treating anal margin cancers in a similar fashion, especially for larger and more advanced lesions, thus avoiding an APR. Several studies have included both perianal and anal canal SCC patients, making it difficult to delineate the outcomes of various treatments. Therapy for small lesions in the perianal area consists mainly of wide local excision, which is consistent with treatment for SCC in other cutaneous locations. Patients with T1 (< 2 cm) and T2 (2 to 5 cm) lesions can be successfully treated with single-modality therapy using either radiotherapy alone or local excision.40,41 Wide local excision is performed by ensuring a 1-cm margin around the lesion. For T2 and T3 (> 5 cm) lesions, prophylactic radiation to the groin is recommended because of the increased risk of inguinal lymph node involvement.37,41 Patients with large tumors, nodal involvement, or invasion of the sphincter appear to be most effectively treated with combined modality therapy. Cummings and Couture reported local control with preservation of sphincter function by combined modality therapy in 80% of patients with perianal cancers 3 cm or more in diameter.42 Residual or recurrent cancer can be treated with additional trials of chemoradiation, local excision, or an APR. Grabenbauer et al evaluated whether tumor site predicted outcome in patients with anal carcinoma treated by radiochemotherapy. Patients with small (< 2 cm) perianal lesions were excluded from the study. The authors found that patients with anal margin cancer alone had a less favorable outcome with a 5-year overall survival and colostomy-free survival of 54 and 69%, respectively, compared with patients with anal canal carcinoma with or without perianal skin infiltration.43

SUMMARY

Anal neoplasms are rare. Any suspicious or persistent lesions of the anus should be biopsied to avoid a delay in diagnosis. Perianal Paget's disease and Bowen's disease both carry a risk of invasive carcinoma, and the standard of treatment for both is wide local excision with negative margins. Of concern is the high recurrence rate despite wide local excision. For anal SCC, considerable progress has been made in the management of these tumors, especially anal canal cancer. Success with combined multimodal therapy for anal canal cancer has led to studies demonstrating good outcomes for patients with advanced perianal SCC. For small lesions, wide local excision continues to remain the standard of care. With timely diagnosis and current treatment, good outcomes can be achieved with neoplasms of the anus.

REFERENCES

- 1.Strauss R J, Procaccino J A, Moffa M A. In: Fazio VW, Church JM, Delaney CP, editor. Current Therapy in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. Bowen's disease and Paget's disease. pp. 75–78.

- 2.Gervasoni J E, Jr, Wanebo H J. Cancers of the anal canal and anal margin. Cancer Invest. 2003;21:452–464. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120018238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore H G, Guillem J G. Anal neoplasms. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1233–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(02)00057-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skibber J, Rodriguez-Bigas M A, Gordon P H. Surgical considerations in anal cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2004;13:321–338. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen J T. Precancerous dermatoses: a study of 2 cases of chronic atypical epithelial proliferation. J Cutan Dis. 1912;30:241–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Billingsley K G, Stern L E, Lowy A M, Kahlenberg M S, Thomas C R., Jr Uncommon anal neoplasms. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2004;13:375–388. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck D E, Wexner S D. In: Beck DE, Wexner SD, editor. Fundamentals of Anorectal Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998. Anal neoplasms. pp. 261–277.

- 8.Beck D E, Timmcke A E. Anal margin lesions. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2002;15:277–284. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleary R K, Schaldenbrand J D, Fowler J J, et al. Perianal Bowen's disease and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:945–951. doi: 10.1007/BF02237107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corman M L. Colon and Rectal Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 657–663.pp. 1063–1065.

- 11.Frisch M, Biggar R J, Goedert J J. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1500–1510. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.18.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beck D E, Fazio V W, Jagelman D G, Lavery I C. Perianal Bowen's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:419–422. doi: 10.1007/BF02552608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarmiento J M, Wolff B G, Burgart L J, Frizelle F A, Ilstrup D M. Perianal Bowen's disease: associated tumors, human papillomavirus, surgery and other controversies. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:912–917. doi: 10.1007/BF02051198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marchesa P, Fazio V W, Oliart S, Goldblum J R, Lavery I C. Perianal Bowen's disease: a clinicopathologic study of 47 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:1286–1293. doi: 10.1007/BF02050810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margenthaler J A, Dietz D W, Mutch M G, Birnbaum E H, Kodner I J, Fleshman J W. Outcomes, risk of other malignancies, and need for formal mapping procedures in patients with perianal Bowen's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1655–1661. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0662-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassan I, Horgan A F, Nivatvongs S. V-Y island flaps for repair of large perianal defects. Am J Surg. 2001;181:363–365. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Holt P J. Cryotherapy for skin cancer: results over a 5-year period using liquid nitrogen spray cryosurgery. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119:231–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boynton K K, Bjorkman D J. Argon laser therapy for perianal Bowen's disease: a case report. Lasers Surg Med. 1991;11:385–387. doi: 10.1002/lsm.1900110412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones C M, Mang T, Cooper M, Wilson B D, Stoll H L. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of Bowen's disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;27:979–982. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(92)70298-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Runfola M A, Weber T K, Rodriguez-Bigas M A, Dougherty T J, Petrelli N J. Photodynamic therapy for residual neoplasms of the perianal skin. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:499–502. doi: 10.1007/BF02237193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramos R, Salinas H, Tucker L. Conservative approach to the treatment of Bowen's disease of the anus. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:712–715. doi: 10.1007/BF02554979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldstone S E, Kawalkek A Z, Huyett J W. Infrared coagulator: a useful tool for treating anal squamous intraepithelial lesions. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1042–1054. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0889-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham B D, Jetmore A B, Foote J E, Arnold L K. Topical 5-fluorouracil in the management of extensive anal Bowen's disease: a preferred approach. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:444–450. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbesman H, Ransohoff D F. Is Bowen's disease a predictor for the development of internal malignancy? A methodological critique of the literature. JAMA. 1987;257:516–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaeger A B, Gramkow A, Hjalgrim H, Melbye M, Frisch M. Bowen disease and risk of subsequent malignant neoplasms: a population-based cohort study of 1147 patients. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:790–793. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.7.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chute C G, Chuang T Y, Bergstralh E J, Su W P. The subsequent risk of internal cancer with Bowen's disease: a population-based study. JAMA. 1991;266:816–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen S L, Sjolin K E, Shokouh-Amiri M H, Hagen K, Harling H. Paget's disease of the anal margin. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1089–1092. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800751113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beck D E, Fazio V W. Perianal Paget's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:263–267. doi: 10.1007/BF02556169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCarter M D, Quan S H, Busam K, Paty P P, Wong D, Guillem J G. Long-term outcome of perianal Paget's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:612–616. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6618-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchesa P, Fazio V W, Oliart S, Goldblum J R, Lavery I C, Milsom J W. Long-term outcome of patients with perianal Paget's disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:475–480. doi: 10.1007/BF02303671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lam D T, Batista O, Weiss E G, Nogueras J J, Wexner S D. Staged excision and split-thickness skin graft for circumferential perianal Paget's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:868–870. doi: 10.1007/BF02234711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newlin H E, Zlotecki R A, Morris C G, Hochwald S N, Riggs C E, Mendenhall W M. Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal margin. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:55–62. doi: 10.1002/jso.20054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjorge T, Engeland A, Luostarinen T, et al. Human papillomavirus infection as a risk factor for anal and perianal skin cancer in a prospective study. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:61–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frisch M, Glimelius B, den Brule A JC van, et al. Sexually transmitted infection as a cause of anal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711063371904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jensen S L, Hagen K, Harling H, et al. Long-term prognosis after radical treatment for squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal canal and anal margin. Dis Colon Rectum. 1988;31:273–278. doi: 10.1007/BF02554359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chawla A K, Willett C G. Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal and anal margin. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:321–344. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70215-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Papillon J, Chassard J L. Respective roles of radiotherapy and surgery in the management of epidermoid carcinoma of the anal margin. Series of 57 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:422–429. doi: 10.1007/BF02049397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Joint Committee on Cancer AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1997. pp. 31–46.

- 39.Nigro N D, Vaitkevicius V K, Considine B. Combined therapy for cancer of the anal canal. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:354–356. doi: 10.1007/BF02586980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuchshuber P R, Rodriguez-Bigas M, Weber T, Petrelli N J. Anal canal and perianal epidermoid cancers. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185:494–505. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00094-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendenhall W M, Zloteck R A, Vauthey J N, Copeland E M., III Squamous cell carcinoma of the anal margin treated with radiotherapy. Surg Oncol. 1996;5:29–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cummings B J, Couture J. In: Fazio VW, Church JM, Delaney CP, editor. Current Therapy in Colon and Rectal Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. Anal carcinoma. pp. 83–88.

- 43.Grabenbauer G G, Kessler H, Matzel K E, Sauer R, Hohenberger W, Schneider I HF. Tumor site predicts outcome after radiochemotherapy in squamous-cell carcinoma of the anal region: long-term results of 101 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1742–1751. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0098-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]