ABSTRACT

Fecal impaction is a common gastrointestinal problem and a potential source of major morbidity. Prompt identification and treatment minimize the risks of complications. Treatment options include manual extraction and proximal or distal washout. Following treatment, possible etiologies should be sought and preventive therapy instituted.

Keywords: Fecal impaction, constipation

Fecal impaction is a common gastrointestinal disorder and a source of significant patient suffering with potential for major morbidity.1 Despite a multimillion dollar laxative industry in our bowel-conscious society, fecal impaction remains an overlooked condition. The incidence of fecal impaction increases with age and dramatically impairs the quality of life in the elderly.2 Read and colleagues found that 42% of patients in a geriatric ward had a fecal impaction.3

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The etiologic factors responsible for constipation can also lead to fecal impaction as an acute complication. Most of these factors are listed in Table 1.2,4 One of the most important risk factors is inadequate dietary fiber and water. An increase in fiber intake to 30 g/day coupled with adequate hydration helps prevent constipation and fecal impaction by poorly diluted fiber. Lack of mobility because of aging or spinal cord injury may also cause fecal impaction related to reduction of colonic mass movements and an inability to use abdominal muscles to assist in defecation. Medications known to retard gastrointestinal motility include opiate analgesics, anticholinergic agents, calcium channel blockers, antacids, and iron preparations.2 Paradoxically, laxative abuse is associated with constipation and fecal impaction. The laxative-dependent patient is unable to produce a normal response to colonic distention and progressively requires higher doses to achieve a bowel movement.5 Congenital and acquired conditions of the colon and rectum, including Hirschsprung's disease and Chagas' disease, can also cause fecal impaction.6 In addition to these etiologic factors, anatomic and functional abnormalities of the anorectum should be considered and excluded.7

Table 1.

Etiologies of Fecal Impaction

| Chronic constipation |

| Anatomic |

| Metabolic |

| Dietary |

| Medications |

| Neurogenic |

| Anatomic anorectal abnormalities |

| Megarectum |

| Anorectal stenosis |

| Neoplasm |

| Functional anorectal abnormalities |

| Increased rectal compliance |

| Abnormal rectal sensation |

CLINICAL PRESENTATION AND EVALUATION

The typical presenting symptoms of fecal impaction are similar to those found in intestinal obstruction from any cause, including abdominal pain and distention, nausea, vomiting, and anorexia.6 These are summarized in Table 2.2 A retrospective review by Gurll and Steer revealed that 39% of patients with fecal impaction had a history of prior impactions.8 These symptoms result from hardened stool impacted in the rectum or distal sigmoid colon with subsequent obstruction. Additional complications such as stercoral ulceration, rectovaginal fistula, megacolon, and colonic perforation may ensue.9 Elderly or institutionalized patients with dementia or psychosis may present with paradoxic diarrhea and fecal incontinence.6

Table 2.

Symptoms Associated with Fecal Impaction

| Constipation |

| Rectal discomfort |

| Anorexia |

| Nausea |

| Vomiting |

| Abdominal pain |

| Paradoxic diarrhea |

| Fecal incontinence |

| Urinary frequency |

| Urinary overflow incontinence |

Following a complete history and physical examination, plain abdominal films are indicated to search for intraluminal feces or signs of obstruction (Fig. 1). The presence of bowel obstruction as evidenced by dilated small bowel or colon with air-fluid levels contraindicates attempts at proximal softening or washout using oral solutions. Examination of the abdomen may reveal a malleable, tubular structure indicating a stool-filled rectosigmoid. Signs of perforation (tenderness or peritoneal signs) are generally absent.4 Although most impactions occur in the rectal vault, the absence of palpable stool does not rule out a fecal impaction.6

Figure 1.

Abdominal radiograph showing fecal impaction.

TREATMENT

Treatment is aimed at relieving the major complaint and correcting the underlying pathophysiology to prevent recurrence. Fecal impaction in the rectum often requires digital fragmentation and mechanical removal.1

Manual Disimpaction

If hardened stool is palpable in the rectum, it may require manual fragmentation or disimpaction. A lubricated, gloved index finger is inserted into the rectum and the hardened stool is gently broken up using a scissoring motion. The finger is then moved in a circular manner, bent slightly and removed, extracting stool with it. This maneuver is repeated until the rectum is cleared of hardened stool. Manual disimpaction may be aided by the use of an anal retractor (i.e., Hill-Ferguson retractor).4

Distal Softening or Washout

Softening of hardened stool and stimulation of evacuation with enemas and suppositories is often helpful. A variety of enema solutions are available, and each has characteristics that may be useful in selected patients. Most enema solutions contain water and an osmotic agent. One such combination contains water, docusate sodium syrup (Colace; Shire US Inc, Florence, KY), and sorbitol. Docusate sodium is a surface-active agent that helps soften the stool as it mixes with water.4 Sorbitol is a sugar alcohol that acts as an osmotic agent. Rectally administered solutions mechanically soften the impacted stool and the additional volume gently stimulates the rectum to evacuate.

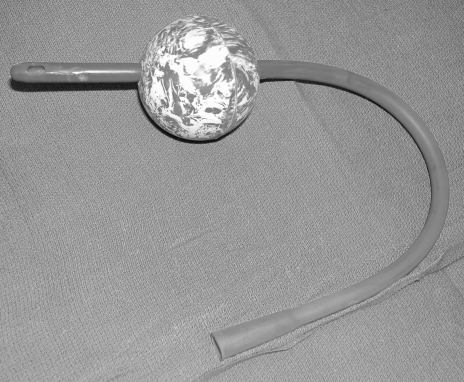

During enema administration, the patient is placed in the Sims' position with a plastic bag under the hips. The enema is given using a 24 French rubber catheter that is passed through a rubber ball (i.e., tennis ball, Fig. 2). The ball allows the administrator to maintain a seal against the patient's anus. Balloon-tipped catheters are not used as they may damage the distal rectum and generally do not maintain an adequate seal.4 The pressure and volume of enema administration must be appropriate. Enema pressure is controlled by the height of the solution reservoir. Limiting the reservoir height to 3 feet above the anus maintains an adequate pressure limit. The volume and rate of fluid administration are guided by the size of the patient's rectum and the degree of fullness symptoms. Administration of smaller volumes (1–2 L) may be more beneficial than a single large-volume enema. A slower rate of enema administration produces less patient discomfort, aids in mixing of solution, and allows instillation of a larger volume. The patient's sensation of fullness is a helpful guide during enema instillation. Volumes or rates that produce discomfort in the patient are avoided.4

Figure 2.

Catheter suitable for enema administration.

When administration is complete, a few minutes are allowed for the solution to mix with and soften the stool. Gentle massaging of the lower abdomen often aids in mixing the combination. The patient then voluntarily evacuates the enema-stool mixture. Additional, gentle abdominal manipulation often helps in evacuation. Ambulatory patients can evacuate more efficiently by using a commode. This process is repeated until the symptoms are relieved and returns are clear.4

Proximal Softening or Washout

Oral lavage with polyethylene glycol solutions containing electrolytes (GoLYTELY or NuLytely, Braintree Laboratories, Braintree, MA; CoLyte, Schwartz Pharma, Milwaukee, WI) may be used to soften or wash out proximal stool.3 Such solutions without electrolytes (MiraLax, Braintree Laboratories, Braintree, MA) have also been used. This technique is contraindicated when a bowel obstruction exists.

The volume and rate of oral lavage are dependent on the patient's size. To treat childhood fecal impaction, Youssef and coworkers recommend 1 to 1.5 g/kg/day of polyethylene glycol solution (PEG 3350, MiraLax).7 For adults, oral regimens vary from 1 to 2 L of polyethylene glycol with electrolytes or 17 g of PEG 3350 in 4 to 8 oz of water every 15 minutes until the patient begins passing stool or eight glasses have been consumed.10 Development of nausea, vomiting, or significant abdominal discomfort prompts cessation of fluid intake.

Other osmotic laxatives such as oral sodium phosphate (Fleet® Phopho-Soda, C.B. Fleet, Lynchburg, VA) have also been used for proximal lavage. Fifteen milliliters of sodium phosphate orally with 4 oz of clear liquids every 4 to 8 hours is a common regimen. Phosphate-containing solutions are contraindicated in patients with renal insufficiency and congestive heart failure.

SPECIAL SITUATIONS

Barium Impaction

Following barium radiographic studies (barium enema and upper gastrointestinal studies), the barium may be retained in the colon and become impacted with stool. Barium is not water soluble and becomes inspissated in the colon when the water is absorbed. Anatomic or functional abnormalities of the lower gastrointestinal tract can predispose to such impactions.

Patients undergoing barium studies should ingest additional fluids following the examination to prevent a barium impaction. Use of a laxative such as milk of magnesia may also be beneficial. Medical advice should be sought if no bowel movement occurs within 48 hours of the radiologic examination or symptoms of fecal impaction develop.

The presence of a barium impaction is readily apparent on plain films. An anteroposterior or lateral abdominal film reveals the amount and location of the retained barium. The absence of signs of perforation (contrast extravasation or free air) or bowel obstruction should also be confirmed. Perforation generally requires operative management. In the absence of perforation or obstruction, removal of barium impaction should proceed as outlined earlier.

Anorectal Surgery

Fecal impaction following anorectal surgery is a rare but serious complication. Buls and Goldberg reported a 0.4% incidence of impaction after operative hemorrhoidectomy.11 Fecal impaction occurring after anorectal surgery is multifactorial. Opiates used for pain relief in the postoperative period have significant constipating action. Anal canal edema and sphincter spasm also compound the problem. Patients' fear of pain associated with bowel movements may lead to deference of bowel movements, resulting in hardened, impacted stool. The presence of a significant impaction is suggested by a history of infrequent bowel movements and perineal pressure and pain.

Mild impactions are relieved with the gentle administration of a retention enema. Posthemorrhoidectomy patients with significant impactions often require disimpaction under anesthesia. An anal block can be administered in the operating room or the endoscopy suite in combination with conscious sedation. Xylocaine 0.5% or 1% with or without epinephrine is injected around the anus and into the anal sphincter complex. A small anal retractor is helpful in guiding needle placement. The fecal impaction may be gently digitally removed once the local anesthetic takes effect.4

After removal of the impaction, the patient should be placed on additional stool softeners and laxatives and advised on the importance of regular bowel movements.

Post-Treatment Evaluation and Prevention

When the impaction has been adequately treated, possible etiologies are explored. A total colonic evaluation (colonoscopy or barium enema) should be performed to reveal anatomic abnormalities (stricture or malignancy). Endocrine and metabolic screening, including thyroid function tests, is also indicated.6

In the absence of an anatomic abnormality, a bulking agent (psyllium, methylcellulose) or an osmotic agent such as polyethylene glycol (MiraLax®) is administered to produce soft regular bowel movements. Other risk factors such as depression, immobility, lack of exercise, and inadequate access to toilet facilities should also be corrected.2

SUMMARY

In summary, fecal impaction is a common gastrointestinal problem. Prompt identification and treatment minimize patients' discomfort and potential morbidity. Treatment options include digital disimpaction and proximal or distal washout. Following treatment, possible etiologies should be found and preventive therapy instituted to avoid recurrence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tracey J. Fecal impaction: not always a benign condition. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30:228–229. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Lillo A R, Rose S. Functional bowel disorders in the geriatric patient: constipation, fecal impaction, and fecal incontinence. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:901–905. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01926.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Read N W, Abouzekry L, Read M G, Howell P, Ottewell D, Donnelly T C. Anorectal function in elderly patients with fecal impaction. Gastroenterology. 1985;89:959–966. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90194-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck D E. Fecal impaction. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;6:41–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reichel W. The Geriatric Patient. New York: HP Publishing Co; 1978. p. 78.

- 6.Wrenn K. Fecal impaction. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:658–662. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909073211007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Youssef N N, Peters J M, Henderson W. Dose response of PEG 3350 for the treatment of childhood fecal impaction. J Pediatr. 2002;141:410–414. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.126603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurll N, Steer M. Diagnostic and therapeutic considerations for fecal impaction. Dis Colon Rectum. 1975;18:507–511. doi: 10.1007/BF02587220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwartz J, Rabinowitz H, Rozenfeld V, Leibovitz A, Stelian J, Habot B. Rectovaginal fistula associated with fecal impaction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992;40:641. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb02121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DiPalma J A, Smith J R, Cleveland M. Overnight efficacy of polyethylene glycol laxative. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1776–1779. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buls J G, Goldberg S M. Modern management of hemorrhoids. Surg Clin North Am. 1978;58:469–478. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)41530-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]