ABSTRACT

Stoma creation is a mental and technical exercise, often straightforward without any difficulty. However, creation of a protruding, tension free, well-vascularized stoma in an obese individual with a thick abdominal wall and short, thickened mesentery can be a substantial challenge. Preoperative planning including stoma site marking, thoughtful consideration of all alternatives, and attention to technical detail will help create a stoma that will serve the ostomate well. The technical tips provided in this article should facilitate the process of selecting the appropriate intestinal segment, identifying the correct stoma site, and creating a functional stoma even in the most challenging situations.

Keywords: Colostomy, ileostomy, technical, pseudo-loop stoma, end-loop stoma

Intestinal stomas, although often a minor component of a major operation from the surgeon's viewpoint, essentially always leave the most lasting impact upon the patient. When the patient has been discharged from the hospital, when the pain has subsided, when the wound has healed the dominant memory and change in the patient's lifestyle will be directly caused by the stoma. Whether temporary or permanent, the ileostomy or colostomy will require more of the patient's attention than any other affects brought on by surgery. That lasting change should be remembered and emphasized throughout the entire process of stoma creation. The process not only involves the manual act of making the stoma, but also involves choosing the correct stoma site and identifying the appropriate intestinal segment. The process must begin prior to the operation, whether elective or emergent, and must involve understanding an individual's lifestyle, clothing preferences, bowel function, and disabilities (if any). The stoma's purpose and the likelihood it will be temporary or permanent, also play important roles in stoma selection. The patient's body habitus and prior surgical scars will also influence stoma site selection and must be evaluated.

Understanding all the components necessary for creation of a successful stoma that will have minimal impact on an ostomate's life is the first and most important step. Without this thought process, it is unlikely an appropriate stoma will be created. In many individuals, these components are simple and require only a few passing moments in a surgeon's operative process. However, in complex and difficult situations, often during urgent operations, this process can be quite complex and will demand much of the surgeon's attention.

The following paragraphs will emphasize the important components of creating a stoma in difficult situations and hopefully provide useful tips that will result in the fashioning of a well-formed stoma from the appropriate intestinal segment, located in the appropriate place on the abdominal wall, designed to perform the function it was intended to do.

Relegating the process of stoma creation to an unsupervised junior resident, often with minimal experience, and only developing technical skills is never appropriate. This delegation of responsibility implies that the surgeon may be concerned about “saving the patient's life,” but not the “quality of his or her life.” The creation of a colostomy or an ileostomy requires a team approach including the operating surgeon, surgical trainees, an enterostomal therapist, and surgical support staff. It is an excellent opportunity for education and if well done, will be a learning experience for the surgical team and have minimal impact on the future ostomate's quality of life.

AVOIDING STOMAS

Although this is a technical chapter detailing stoma creation, a few words concerning avoiding a stoma bear merit. When planning for a temporary or permanent stoma one should ask, “Is this stoma necessary?” Or perhaps a better question, “Will the stoma provide the best possible functional result for my patient in this situation?” In addition, “Am I creating the stoma that will lead to the simplest, safest future reversal if appropriate?”

Current data challenges the need for stomas in urgent operations with unprepped bowel. In some circumstances, a primary anastomosis may be safer than creation of a stoma. That discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, but should be remembered and carefully considered before creating any stoma.

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

All preoperative conversations involve informed consent; this is particularly important when a stoma may be created, especially in emergency situations when a patient is likely to be completely unaware that he or she may need an ileostomy or colostomy. The conversation must extend beyond this to assess disabilities, clothing styles, occupation, and living circumstances. For example, an elderly person living alone with poor vision or with significant arthritis may not be able to care for a stoma and therefore may lose his or her ability to live independently. Alternatively, a carpenter may have significant difficulty wearing a tool belt if his stoma is placed improperly, preventing him from working. These factors contribute not only to stoma siting, but also to the decision whether or not to create a stoma. In some cases, a primary anastomosis, with slightly greater operative risk, may be preferable to a stoma that severely impacts a patient's lifestyle. These risks and benefits cannot be properly assessed without taking the time to understand a patient's living situation.

In addition to lifestyle considerations, bowel habits must be evaluated. Individuals with modest impairments in continence may become totally incontinent after rectal resection and low pelvic anastomosis. In these situations, a stoma will likely achieve the best functional results.

In elective situations, many patients are able to meet with an enterostomal therapist for preoperative education and stoma site selection. However, in urgent situations (or if an enterostomal therapist is not available), the surgeon must select and mark the stoma site. This should almost always be done prior to surgery; marking in the operating room cannot be done properly.

In routine situations, marking begins with identifying the “ostomy triangle” bounded by the anterior superior iliac spine, the pubic tubercle, and the umbilicus. The stoma, ileostomy traditionally on the right and colostomy on the left, is placed in the center of this triangle, through the rectus muscle slightly below the umbilicus. The site should be 5 cm away from skin folds, prior scars or bony prominences, and the patient's belt line. This will allow for proper fitting of the stoma appliance. However, in difficult situations, such as a large patient, with a thick abdominal wall (particularly if there is a large abdominal pannis) marking superior to the umbilicus will facilitate both stoma creation (there is less fat above the umbilicus allowing for easier stoma construction) and stoma care (it is very difficult for obese patients to see stomas below their umbilicus). Individuals with disabilities, such as a spinal cord injury, should be marked in the position they spend most time, as this will facilitate appliance fitting and care.

Once a site has been selected in the supine position, the patient should sit, and if possible stand, to ensure no significant skin folds or crevasses have developed. If the previously identified site now lies in a crease or fold, an alternative site should be selected.

PREPARING FOR THE FUTURE

This selection applies to the creation of “temporary stomas” and involves selection of the proper intestinal segment, stoma location, and stoma type. At the time of primary operation (usually emergency surgery), the surgeon thinks primarily about solving the immediate problem at hand (i.e., obstructed colon or perforated diverticulitis); nevertheless he or she must also think about the patient's life after surgery. When the patient recovers, what type of stoma he or she will be left with, is it likely to be permanent, and what will be necessary for stomal reversal are issues to be considered. These factors may seem unimportant in a patient with intraabdominal sepsis, but they will seem very important 3 months later at the time of contemplated stoma takedown. How often do we hear or say, “If I had only taken a few more minutes to …, it would have made this second operation so much easier”.

The first important choice involves selection of the intestinal segment for stoma creation. If the stoma might be permanent due to age or comorbidity (even though it is initially created as a “temporary” stoma), the intestinal segment most likely to result in the best stoma should be used. For example, if a left colectomy from the mid-transverse colon to the distal sigmoid colon is necessary for ischemic colitis, a stoma could possibly be created from the proximal transverse colon. However, if the stoma is more likely to be permanent than temporary, resecting the remaining right colon with creation of an end ileostomy is more appropriate as an ileostomy in the right lower quadrant is much preferred to a mid-transverse colostomy in the upper abdomen.1

Alternatively, if stoma reversal is likely and intestinal length is important (i.e., patients with chronic diarrhea or marginal continence) then intestine should be preserved at the expense of a less desirable stoma. For example, if an otherwise healthy patient with chronic diarrhea requires a left colectomy for colonic ischemia similar to the prior patient, then the right colon and ileocecal valve should be preserved with a resulting mid-transverse colostomy. Even though this stoma is undesirable, the additional intestinal length will be important following the likely reestablishment of intestinal continuity.

DIVIDED-LOOP STOMAS

When creating a temporary stoma it is always preferable, if possible, to bring the proximal and distal bowel loops through the same trephine in the abdominal wall. Among other advantages, this will allow for stoma takedown without a formal laparotomy. With standard loop stomas, this occurs by definition, but in other circumstances it only occurs through proper technique. Divided-loop stomas2 can be created with remote intestinal segments following bowel resection. They consist of a divided-loop ileo-ileostomy, ileo-colostomy, or colo-colostomy. As an example, a right colectomy is performed for right colonic trauma and anastomosis is deemed unsafe due to hemodynamic instability, the stapled end of the transverse colon is traditionally left in the abdominal cavity and the terminal ileum is brought out as an end ileostomy in the right lower quadrant. To reestablish intestinal continuity, a laparotomy is required. A better alternative would be to bring the terminal ileum and the antimesenteric corner of the stapled transverse colon through a single trephine on the right side of the abdominal wall, an end-loop ileo-colostomy (see Fig. 1). With this technique, intestinal continuity can be reestablished through the stoma site without the need for laparotomy. Similar stomas can be performed following small bowel or left colon resections.

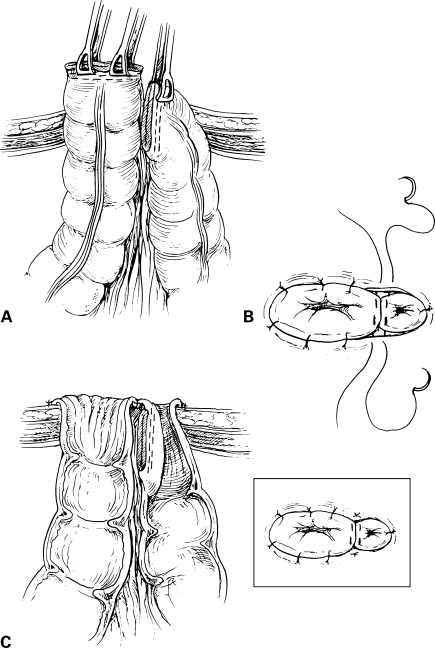

Figure 1.

End loop cstoma (Prasad). (A) The entire divided edge of the proximal limb and the antimesenteric corner of the distal limb are gently drawn through the opening in the abdominal wall. After the abdomen has been closed, the staple line of the proximal limb is excised completely and only the antimesenteric corner of the distal staple line is removed. (B) The proximal limb is matured flush with the skin by suturing the deep dermal skin to full-thickness colon with absorbable sutures. Transition sutures may be placed to help mature the mucous fistula, which has the appearance of a “mini-stoma”. (C) Sagittal view of the completed end-loop colostomy. Note the portion of the distal staple line in the subcutaneous tissue.

PREPARATION FOR HARTMANN TAKEDOWN

Henri Hartmann's operation, sigmoid colostomy, oversewing of the rectal stump, and creation of an end descending colostomy, has been the mainstay of urgent surgery for left colonic emergencies since the mid-1900s. However, it is slowly being replaced by other alternatives, mostly due to the difficulty of the Hartmann takedown. Hartmann reversal is never an easy operation, but there are several maneuvers that can be performed at the time of the primary operation, which will help facilitate the second surgery.

At the time of stoma reversal, essentially all the difficulty surrounds identification and preparation of the rectal stump for reanastomosis. To facilitate that process, if possible, the distal segment should be brought through the same stoma trephine as the proximal segment creating a divided-loop colostomy. This will alleviate the need for laparotomy at the time of reversal. If this is not possible, the distal transection site should be sewn to the underside of the anterior abdominal wall in the left lower quadrant, as close to the colostomy site as possible. With both ends in proximity, a mini-laparotomy with limited adhesiolysis may be possible for reversal.

Unfortunately, in most Hartmann operations, a short rectal stump will preclude both of the above options. Despite a short rectal segment, several maneuvers will be beneficial. First, avoid dissection of the extraperitoneal rectum. This is rarely necessary. Leaving these planes undissected at the primary operation will prevent extraperitoneal scarring, which can lead to shortening and retraction of the rectal stump. This will make the rectum difficult to identify and subsequent passage of the transanal circular stapler very challenging. Second, sew the rectum, on stretch, to the sacral promontory; this will minimize retraction of the rectal staple line into the deep pelvis. Third, mark the rectal transection line with long, nonabsorbable sutures. There will often be multiple small bowel loops adherent in the pelvis and early identification of the rectum will eliminate confusion and avoid unnecessary dissection. Finally, the application of Seprafilm® (Genzyme Corp., Cambridge, MA) in the pelvis and under the anterior abdominal wall may minimize adhesions, making dissection at the time of the second surgery less difficult.

THE DISTENDED COLON

Stomas are often created in cases of a large bowel obstruction. The distended, obstructed colon presents three problems relating to stoma construction. First, the obstructed colon is by nature ischemic; therefore, it is difficult to assess stoma vascularity. Second, the mobility of an obstructed colonic segment is impaired, making it challenging to create a stoma that protrudes appropriately through the abdominal wall. Third, the dilated colon only passes through a large abdominal wall orifice, which can eventually lead to a parastomal hernia.

Decompression of the obstructed segment corrects all these difficulties. In extreme situations, this can be accomplished prior to passing the bowel through the abdominal wall. However, most often this can be performed after passing the intestinal segment through the abdominal wall stoma site.

In this situation, it is beneficial to mature the stoma prior to closing the abdominal incision. The colon is passed through the previously created stoma site. The staple line is resected and the bowel decompressed after protecting the operative field with towels. Once the bowel has been decompressed, it becomes more mobile and can be advanced further out of the abdomen. Its viability can be assessed. If the stoma's vascularity is adequate, it can be matured in standard fashion. If not, the colon can be further mobilized (as the abdomen is still open) and a well-perfused segment matured. This technique does increase the risk of intraabdominal contamination, but can be helpful in select situations.

THE DIFFICULT COLOSTOMY

The classic situation leading to difficult colostomy creation occurs following emergency diverticular resection in an obese man with a shortened, thickened mesentery and a very thick abdominal wall. In this situation, creation of a well-perfused protruding colostomy can be very challenging. As previously mentioned, preoperative stoma site marking, particularly a site above the umbilicus, can be beneficial. The well-mobilized descending colon will often protrude through the upper abdominal wall with less tension compared to the lower abdomen. In addition, there is often significantly less adipose tissue above the umbilicus. Finally, obese individuals manage upper abdominal stomas better than lower abdominal stomas because of better visibility.

The following steps will facilitate stoma creation in most circumstances:

Is there any safe alternative to colostomy creation? i.e., in some individuals a primary anastomosis may, in fact, be safer than creation of a difficult left-sided colostomy (a diverting ileostomy can be considered following creation of an anastomosis if necessary).

All inflamed sigmoid colon should be excised.

The segment of colon used for the colostomy should be free of inflammation, thickening, or edema.

The lateral peritoneal reflection should be taken-down completely leaving the left colon attached only by its midline mesentery.

Medial peritoneal attachments at the base of the colonic mesentery should be transected to increase mobility.

The splenic flexure should be fully mobilized.

The inferior mesenteric artery proximal to the take off of the left colic artery can be ligated if necessary to provided additional length.

“Windows” can be created in the medial and lateral aspects of the mesocolon to increase length.

The mesentery adjacent to the terminal left colon can be trimmed provided that a 1-cm segment of mesentery containing the marginal artery is left attached to the colon wall.

An oversized abdominal trephine will often allow passage of a thick colonic mesentery, preventing venous congestion and subsequent stomal ischemia.

A stoma site above the umbilicus, as previously mentioned, will decrease the thickness of the abdominal wall through which the colon must pass and often further decrease tension as mobilized left colon reaches most easily to the abdominal wall above the umbilicus.

In rare circumstances, despite all the previously mentioned maneuvers, it remains impossible to create a well-perfused, tension-free colostomy. If appropriate, an ileostomy may be possible when a colostomy is not. However, when an ileostomy is not a viable alternative a “pseudo-loop colostomy” can be created (see Fig. 2).3 The previously mentioned 11 steps should be followed. A segment of the colon several centimeters proximal to the stapled portion is selected. An oversized trephine is created in the portion of the abdominal wall that results in the least colonic tension. Next, only the antimesenteric boarder of the previously selected colonic segment is passed through the abdominal wall. A small colotomy is made in the protruding bowel and the antimesenteric boarder is primarily matured to the skin without eversion (see Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The “pseudo-loop” (end loop) colostomy can be employed in rare cases when no other stoma can reach the abdominal skin.

This will create a “less than ideal” stoma that will function appropriately as the patient recovers from his or her emergency surgery. Later, revision may be required.

DIFFICULT ILEOSTOMY

Creating a well-perfused, tension-free ileostomy, whether end or loop is rarely as difficult as fashioning a challenging left-sided colostomy. However, obese abdominal walls and short thickened mesenteries can make even an ileostomy difficult. The following guidelines should prove beneficial in these situations.

Supraumbilical placement, particularly in the obese individual is often beneficial.

Mobilization of the small bowel mesentery to the base of the duodenum as done for an ileal-pouch anal anastomosis often results in substantial mobility.

Ileocolic artery can nearly at always be ligated at its origin without subsequent stomal ischemia.

An oversized abdominal wall trephine is beneficial in decreasing tension and improving perfusion in thickened bowel with short mesentery.

Although not ideal, a “noneverted” ileostomy can be created in an emergency situation.

Very rarely, despite these maneuvers, it is impossible to create a viable ileostomy. Again, a “pseudo-loop ileostomy” may provide the answer. A pseudo-loop ileostomy is created similar to the previously described pseudo-loop colostomy (see Fig. 2), substituting the ileum several centimeters proximal to the end ileal staple line. Management and pouching of this stoma will be difficult for the patient and the enterostomal therapist. If the stoma is created for temporary diversion, early takedown may be necessary. If designed to be permanent, revision will certainly be necessary following appropriate postoperative recovery.

In challenging situations, risk benefit ratios must be evaluated, and choices made; ideal bowel segment versus ideal stoma versus ideal stoma location. When weighing these issues, we should all remember an important lesson taught to us by our stoma therapists and by our ostomates. “Better to create an ugly stoma in a good location, than to create a pretty stoma in an ugly location,” or as the realtors remind us when buying a home, “location, location, location.”

ASSESSING THE COMPROMISED STOMA

Despite best efforts, stomas with marginal viability are created and must be evaluated and managed in the perioperative period. Nearly all early postoperative stoma-related problems are due to ischemia. Ischemia can be mucosal, muscular, or full-thickness. Any of these degrees of ischemia can be suprafascial of subfascial.

The degree of ischemia predicts the natural repair process and the final anatomic result. Mucosal ischemia will resolve without sequelae, muscular ischemia will result in fibrosis and subsequent stenosis. Suprafascial ischemia can be managed electively regardless of its degree, whereas full-thickness, subfascial ischemia must be treated urgently or intraabdominal fecal leakage and its sequelae will develop.

A simple, bedside test will help differentiate the different degrees and locations of intestinal ischemia. A lubricated tube is passed into the stoma orifice and illuminated with a pen light or an ophthalmoscope. If the mucosa is pink no further evaluation is necessary; the ischemia will resolve and the stoma recover fully. If the mucosa appears dark below the fascial level, then the depth of ischemia must be assessed. The stoma should be pricked with a needle, if bright red bleeding appears, the muscle is well perfused and the ischemia is likely to resolve without sequelae. If muscular ischemia exists below the fascia, revision is mandatory. If it is superficial, then two options exist.

If the stoma is designed to be temporary, a stenosis is likely to develop, but can be managed until the time of stoma reversal. However, if a permanent stoma was created, revision will ultimately be necessary, and early postoperative revision is often the best option provided that the patient's medical condition is appropriate.

CONCLUSIONS

Stoma creation is often the last component of a long and difficult operation, and may seem trivial when compared with the essential portions of the surgery. Yet the stoma may be the only lasting effect reminding the patient of his or her medical condition and surgery. It will have the largest impact on our patient's quality of life.

Therefore, stomas, whether permanent or temporary, should be constructed to last a lifetime. Each stoma is an enterocutaneous anastomosis and the principles important in any anastomosis extend to stoma creation. Thoughtful, technically correct stoma creation will lead to well-fashioned stomas that will have minimal impact upon the quality of life of ostomates. Hopefully the technical tips provided in this chapter will facilitate successful stoma creation even in difficult circumstances. Prior to creating any stoma, the surgeon should review these considerations: Can the stoma be safely avoided? Is the stoma in the best possible location, using the most appropriate intestinal segment? Has everything been done to facilitate stoma reversal and reestablishment of intestinal continuity? Have I created a stoma that (even if designed to be temporary) will last a lifetime?

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams N S, Nasmyth D G, Jones D, et al. Defunctioning stomas: a postoperative controlled trial comparing loop ileostomy with loop transverse colostomy. Br J Surg. 1986;73:566–570. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Unti J A, Abcarian H, Pearl R K, et al. Rodless end-loop stomas: a seven–year experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 1991;34:999–1004. doi: 10.1007/BF02049964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cataldo P A. Technical tips for the difficult stoma. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2002;15:183–190. [Google Scholar]