ABSTRACT

Strictureplasty in patients with Crohn's disease is an option in the colorectal surgeon's armamentarium for fibrostenotic obstructive disease. Common types include the Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty, Finney strictureplasty, and the side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty. The procedure has potential for significant morbidity; therefore, it should be chosen for the patient carefully. Strictureplasty complements bowel resection in Crohn's disease; it is an excellent procedure to reduce the risk of developing short-bowel syndrome and its associated complications.

Keywords: Crohn's disease, strictureplasty, obstruction

Crohn's disease is considered an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which was first described by Crohn, Ginzburg, and Oppenheimer in 1932 as a transmural inflammatory condition of the terminal ileum.1 The exact etiology of Crohn's disease remains largely unknown; however, it is generally agreed that Crohn's disease is likely due to a complex interrelationship between genetics,2 autoimmunity,3 and environmental factors. Crohn's disease occurs more commonly in Caucasians, especially those from northern Europe.4 Recent studies have demonstrated an increasing incidence of Crohn's disease.5 As the incidence of the disease increases, interest in the disease also increases, thus leading to new strategies to treat the disease.

TREATMENT OF CROHN'S DISEASE

Medical Management

The treatment of Crohn's disease is mostly medical, particularly in the early stages without complications. The medical treatment traditionally consists of aminosalicylates for mild-to-moderate disease and steroids for more severe disease. Newer immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine have also been employed based on the idea that the disease is an autoimmune condition. Recently, monoclonal antibody therapy directed against tumor necrosis factor-α (infliximab) has been used with success in the treatment of Crohn's disease.6 These therapies and others unfortunately only provide disease control; none has been shown to provide a cure.

Surgical Management

Surgical treatment of Crohn's disease is usually reserved for complications or failure of medical management. Complications from Crohn's disease include abscess, perforation, fistulae, and obstruction. It should be noted that unlike mucosal ulcerative colitis where total proctocolectomy is usually curative except for a few extraintestinal manifestations, surgical resection in Crohn's disease does not provide a cure, but rather symptom control and regression of disease, which is often temporary. Complicated cases of Crohn's disease are usually best managed by a multidisciplinary medical and surgical approach to the disease.

Despite surgery being a second-line treatment, ~90% of patients with Crohn's disease will ultimately require some type of surgical intervention.7 As mentioned earlier, one of the manifestations of Crohn's disease is bowel obstruction. Bowel obstructions may be caused by adhesions in the patient who has had prior abdominal surgery, but more likely small bowel strictures if the patient has never had a previous abdominal operation or has recurrence of disease. The obstruction may also be caused by inflammation, not necessarily a stricture. In the acute phase, bowel obstruction in this patient population can be treated similarly to a non-Crohn's adhesive small bowel obstruction. Patients are admitted to the hospital for bowel rest, intravenous hydration, and nasogastric tube decompression, with the major difference being the addition of intravenous steroid administration. Failure of medical management with the above measures will require surgical exploration. In Crohn's patients, the traditional 24- to 48-hour observation period for adhesive small bowel obstruction is usually increased, unless there are any signs of bowel compromise that would require immediate exploration.

BOWEL RESECTION

Surgical treatment for intestinal Crohn's disease manifestations can be separated into two groups, resection and bowel-sparing interventions. Traditionally, bowel resection or small bowel bypass to grossly normal-appearing bowel was undertaken. The lost absorptive surface of the small bowel can have significant nutritional consequences for the patient. If large areas of the jejunum are resected or bypassed, there is little consequence in terms of nutrition8; however, if large segments of the ileum are resected, significant nutritional deficiencies may develop. These deficiencies include decreased absorption of bile salts and vitamins A, D, E, K, and B12.8 Fat absorption may also be decreased with large amounts of ileal resections.8 Diarrhea also develops in these patients adding to their already decreased nutritional status.

INTESTINAL STRICTUREPLASTY

Concerns over short-bowel syndrome due to multiple resections and large segment resections have led to the use of bowel-sparing techniques, namely, strictureplasty. Intestinal strictureplasty was first described in India over 25 years ago by Katariya et al9 for multiple tubercular strictures causing bowel obstruction. This was followed by Lee and Papaioannou10 who published their results on strictureplasty for Crohn's disease patients. Their patient group underwent either strictureplasty alone or combined strictureplasty and resection, both of which were shown to be safe and efficacious.10 Multiple studies have been published since that time describing the safety and efficacy of strictureplasty in Crohn's disease.

Recently, nonsurgical endoscopic methods for dealing with Crohn's disease strictures have been advocated to decrease surgery, specifically, endoscopic balloon dilation.11 Couckuyt et al12 reported long-term success in 34 out of 55 patients undergoing endoscopic balloon dilation12; however, there are significant limitations to this method. It is generally accepted that strictures greater than 4 cm in length are not amenable to balloon dilation.11 Strictures beyond the reach of the endoscope, from upper or lower endoscopy, are also not candidates for endoscopic balloon dilation as the endoscope will not be able to safely reach the stricture.11 Complications, including perforation and hemorrhage, are similar to balloon dilation for other pathologies. Endoscopic balloon dilation is an effective treatment option; however, its application in the majority of Crohn's disease patients is still limited.

Indications and Contraindications for Strictureplasty

As discussed earlier, the concern over short-bowel syndrome and the associated nutritional deficiencies in Crohn's disease patients has led to an increased use of bowel-sparing techniques, namely strictureplasty. It should be noted that not all patients are candidates for bowel-preserving procedures. It was originally believed that strictureplasty should only be performed in short-length strictures, but this idea was challenged by Michelassi.13 Now the length of a stricture is not a significant variable when planning strictureplasty except for determining which type of procedure to perform. Another change in practice has been in dealing with strictures at active disease sites.8 Historically, only nonacute fibrotic strictures were considered amenable to strictureplasty, but this procedure has been shown to be safe and effective in cases of active disease.8 The main indications for strictureplasty are bowel procedures in a patient with multiple prior resections with impending short-bowel syndrome. The main contraindications for strictureplasty in Crohn's disease patients are based on nutritional status and type of disease. Table 1 provides a summary of both indications and contraindications for strictureplasty in Crohn's patients.14

Table 1.

Indications and Contraindications for Strictureplasty

| Indications |

| • Multiple strictures over large length of bowel |

| • Previous significant small bowel resection |

| • Patient with short bowel syndrome |

| • Stricture without associated phlegmon or fistula |

| Contraindications |

| • Preoperative malnutrition (albumin < 2.0 g/dL) |

| • Perforated bowel |

| • Multiple strictures over short length of bowel |

| • Stricture short distance from area of resection |

| • Bleeding from planned strictureplasty site |

Stricture formation in Crohn's disease can be separated into three categories: gastroduodenal, intestinal, and anastomotic. The management of each of these conditions warrants discussion. The basic principles of surgical management of Crohn's disease remain true when dealing with any of these etiologies.

GASTRODUODENAL CROHN'S STRICTURE DISEASE

Gastroduodenal involvement of Crohn's disease is a rare condition. The incidence has been reported to be ~0.5 to 4.0% of patients.15 These patients are usually diagnosed very late in their disease state and sometimes after years of symptoms because they are often misdiagnosed and treated for other medical conditions such as acid reflux. Therefore, in patients with a known diagnosis of Crohn's disease, gastroduodenal involvement should be suspected in individuals with any upper gastrointestinal symptoms. The mainstay of therapy for gastroduodenal Crohn's disease remains medical. However, surgical intervention is required in cases of perforation, hemorrhage, and obstruction. In the case of hemorrhage, the principles of non-Crohn's disease upper intestinal hemorrhage management should be followed and endoscopic management is usually successful.

Gastroduodenal obstruction is another indication for surgery in these patients. Patients may often be conservatively managed with nasogastric tube decompression, intravenous hydration, and intravenous steroid therapy. However, this treatment is usually only successful in cases of acute, active disease. Chronic fibrotic disease, such as a stricture, will not respond to these conservative measures. Nonsurgical treatment of gastroduodenal Crohn's disease stricture can be attempted by endoscopic balloon dilation as discussed earlier.11

Surgical Treatment

BYPASS

Surgical treatment of gastroduodenal Crohn's disease stricture is basically separated into two categories: bypass and strictureplasty. Resection, involving possible pancreaticoduodenectomy, in this patient population involves a potentially unacceptable morbidity and mortality for a nonmalignant pathology. Bypass of the involved area was the original way to deal with these patients. Multiple reports of success with bypass using gastrojejunostomy have been reported.16,17,18 Concerns over bypass include nutritional concerns with the decreased absorption of iron, but also involve the physiological consequences associated with gastrojejunostomy. These problems include, but are not limited to, bile reflux gastritis, dumping syndrome, marginal ulceration, and blind-loop syndrome.19 The concern over marginal ulceration has led many surgeons to include a vagotomy19 during the gastrojejunostomy, which can add time and morbidity to the operation. Concerns over using jejunum that may be involved with Crohn's disease to make the gastrojejunostomy anastomosis have also been reported.19 Resection or bypass of a short segment of duodenum with gastroduodenostomy or duodenojejunostomy is also another option that may potentially avoid some of the complications of gastrojejunostomy, but published experience is minimal.19,20

STRICTUREPLASTY

The concerns over gastrojejunostomy in these patients led to the introduction of strictureplasty. Similar procedures in this region had been performed for years in patients without Crohn's disease in the form of pyloroplasty. Indications to perform strictureplasty in the gastroduodenal region include short-segment strictures, strictures in the proximal portions of the duodenum (strictures more distal are not a contraindication), and an adequate nutritional status. Contraindications, although some relative, include poor nutritional status, long-segment strictures, multiple strictures, sepsis, associated abscess or phlegmon, and perforation. Severe inflammation surrounding the tissue may make the mobilization of the duodenum difficult and dangerous; therefore, great care must be employed during the dissection.19 It may be considered a relative contraindication to strictureplasty.

The choice of strictureplasty in the gastroduodenal region is limited to two forms, the Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty and the Finney strictureplasty. The Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty is the choice for short-segment strictures throughout the duodenum; however, the Finney strictureplasty may be more suitable for larger segment strictures, especially when more proximal.19 Other types of strictureplasties may be performed8; however, these two are the most common. If the stricture is involving the pylorus as well as the proximal first portion of the duodenum, the pylorus may be incorporated into the strictureplasty incision and the procedure performed as a pyloroplasty.

To perform a duodenal strictureplasty, a full Kocher maneuver is recommended.19 This mobilization allows for complete inspection of the duodenum and makes the strictureplasty easier to perform. The actual details of the procedure will be discussed later in this review. Another important maneuver that should be undertaken in all strictureplasties in this region is a judicious search for other strictures in this region, either proximally or distally, as these should be dealt with at the time of operation. Simultaneous strictures can easily be missed, especially at the junction of the third and fourth portion of the duodenum.19 One accepted method to detect these occult strictures is performed by passing a deflated urinary catheter distal to the jejunum and then withdrawing the catheter with the balloon inflated, thus detecting any occult strictures during the withdrawal.19 The balloon is usually inflated with 5 cc of fluid that would provide approximately a 2.5 cm diameter, which would be adequate to rule out a stricture. The maneuver is then repeated in the same manner by passing the catheter proximally to detect the presence of any occult proximal strictures.

As the experience with gastroduodenal strictureplasty has increased, there have been variations in the accompanying procedures. For example, early experience included routine use of gastrostomy tube placement at the time of strictureplasty, but this is no longer used.19 The use of vagotomy for cases requiring surgical intervention, whether bypass or strictureplasty, has also changed, but remains an issue of debate.20 Earlier, vagotomy was routinely used in all of these patients; however, it has been used less frequently in more recent experiences with favorable outcomes.19 H2-blockers and proton pump inhibitors decreased the risk of acid-induced marginal ulcers.

Strictureplasty is a safe and viable option for gastroduodenal Crohn's disease refractory to medical management. However, the short- and long-term outcomes are still not consistent among different reports. Worsey et al19 report a 7% recurrence rate (1 out 13 patients) after strictureplasty in this region; however, Yamamoto et al20 report a 46% recurrence rate (6 out of 13 patients) after strictureplasty. The follow-up was 3.5 years and 9 years, respectively. This difference in follow-up may explain the large difference in recurrence rate as more patients in the Worsey group may develop recurrences over time. The world literature on outcomes for strictureplasty for gastroduodenal Crohn's remains small, as this manifestation of Crohn's remains relatively rare. As the experience with strictureplasty for gastroduodenal Crohn's disease grows, a better understanding of the long-term success of strictureplasty will be gained.

SMALL BOWEL STRICTURE DISEASE

Crohn's disease involving the small bowel (jejuno-ileum) is the most common form of the disease despite its pan-intestinal nature. Within the small bowel, the terminal ileum is the most commonly involved area. Clinically, small bowel Crohn's disease may manifest as mild-to-severe abdominal pain, obstruction, fistulae, diarrhea, malnutrition, to perforation and sepsis. Although all of the mentioned manifestations can be severe and debilitating, the focus here will be on obstructive disease secondary to strictures.

Small bowel obstruction due to Crohn's disease can be due to adhesions, secondary to the inflammatory nature of the disease, acute inflammation, and fibrostenotic strictures. All etiologies may be initially treated similarly to non-Crohn's disease bowel obstruction with the addition of intravenous steroids, as mentioned earlier. Patients with adhesive and acute inflammatory disease may have resolution; however, patients with stricture disease will likely not completely recover. The failure of conservative management is one indication that a stricture may be present. Other diagnostic tests that may be beneficial include computed tomography (CT) scan with oral and intravenous contrast and small bowel series with oral contrast. Nuclear white blood cell scans can also be used to determine stricture versus active disease. The small bowel series may be delayed until the acute discomfort of the obstruction has resolved because many patients will not tolerate the multiple positions often required for an adequate study. The small bowel series is also a useful test for patients who have chronic, intermittent obstructive symptoms as it may delineate small bowel strictures and potentially serve as a road map for surgery.

Patients found to have small bowel strictures will usually require interventions because they will subsequently develop bowel obstructions, either from the stricture itself or from a bolus of food obstructing at the stricture site. The bolus of food is more likely to cause the obstruction if the stricture is located more proximally in the small bowel. Conservative management for strictures is usually unsuccessful; therefore, more invasive methods are required.

Surgical Treatment

Surgery remains the mainstay of therapy for strictures in Crohn's disease patients. The surgery consists of resection of the strictured portion of small bowel or bowel sparing surgery. Small bowel stricture disease can also be endoscopically approached if the stricture is accessible to the endoscope; however, most small bowel strictures are not accessible to the endoscope. In addition, endoscopic balloon dilation of Crohn's disease-related strictures is associated with the risk of perforation and sepsis11 and can only be performed on strictures less than 4 cm in length.

RESECTION

Resectional therapy was the traditional mainstay of treatment for Crohn's disease-associated strictures for some time; however, the concern of short-bowel syndrome led to the use of bowel-sparing procedures. The actual length of small bowel remaining in patients is an important consideration in this and all patient groups. Long-term parenteral nutrition will be required if less than 100 cm of bowel is preserved.21 Patients with larger amounts of small bowel length may also suffer from malabsorption and therefore, malnutrition. It is accepted that the less small bowel present, the greater the degree of these complications. Small length isolated resection is usually well tolerated as the remaining small bowel adapts by undergoing structural and functional changes22; but with larger resections, the adaptations are not sufficient to overcome the malabsorption. Although patients may survive with short-bowel syndrome, these patients will usually require partial or total parenteral nutrition, which can have high morbidity and mortality in the long term, as well as a cost of up to $100,000 per year.22 Therefore, in patients with Crohn's disease and any other patients where short-bowel syndrome may be a concern, bowel-preserving procedures should be entertained.

STRICTUREPLASTY

The main bowel-saving procedure for patients with Crohn's disease is strictureplasty. The indications and contraindications for performing strictureplasty are discussed above and summarized in Table 1. Patients with strictures who are not candidates for strictureplasty should undergo resection, keeping in mind that with each resection, there is a higher chance of developing short-bowel syndrome. In this patient population, strictures found incidentally should not be resected as they are not symptomatic and this would further increase the amount of bowel resected. If preoperative nutritional status is a concern, patients can be placed on preoperative parenteral nutrition, as long as the surgery can be safely delayed, as is often the case.

Strictureplasty may be safely undertaken alone or concomitantly with resection.23 If the above criteria are met, especially nutritional criteria, patients having a resection or strictureplasty should also be evaluated for additional asymptomatic strictures. If present, strictureplasty may be performed on these strictures to prevent future symptom occurrence.24

The choices for type of strictureplasty performed in the jejuno-ileal region are greater than the gastro-duodenal region. For short-segment strictures, less than 5 to 10 cm, the Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty remains the procedure of choice.25 For longer segment strictures, the Finney or Jaboulay methods are often employed. Prior to the mid-1990s, long-segment strictures (> 20 cm) were considered indications for resection. In 1996, Michelassi introduced a technique for long strictures and multiple strictures over a limited area as an alternative to resection.13 This method was further supported by a prospective study reported in 2000.26 The technical aspects of these procedures will be described later in the review. Other procedures described include variations of stapled strictureplasty,27,28 which is in essence the creation of a side-to-side anastomosis. It is most useful when several short fibrotic strictures are close together in a patient with an imminent danger of short bowel syndrome. This technique is also useful in the treatment of anastomotic strictures. Variations of the procedure described by Michelassi13 have also been reported.29

There have been multiple studies reporting their experience with strictureplasty. These studies include patients who have undergone different types of strictureplasty and report their outcomes and recurrence rates, some of which are summarized in Table 2.23,30,31,32,33,34,35,36 Overall, it is accepted that strictureplasty of the small bowel is a safe and beneficial alternative to resection in the appropriate patient. It should be noted that over time the recurrence rate can be quite high, but studies have shown no statically significant difference in recurrence after strictureplasty versus resection.37

Table 2.

Series in the Literature Regarding Strictureplasty

| Author | Strictureplasties | Follow-up (Months) | Morbidity (%) | Recurrence (%) | Reoperation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fazio et al23 | 452 | 36 | 23 | 24 | 15 |

| Serra et al30 | 154 | 54 | 19 | 40 | 33 |

| Yamamoto et al31 | 285 | 90 | 18 | 54 | 44 |

| Hurst and Michelassi32 | 109 | 38 | 12 | 22 | 12 |

| Tonelli and Ficari33 | 174 | 50 | 7 | 44 | 23 |

| Dietz et al34 | 1124 | 90 | 18 | 37 | 34 |

| Futami and Arima35 | 293 | 80 | 10 | n/a | 44 |

| Fearnhead et al36 | 479 | 85 | 23 | n/a | 56 |

Tichansky et al38 performed a meta-analysis for strictureplasty for Crohn's disease where they reviewed 15 retrospective studies. The meta-analysis included a review of 506 patients who underwent 1,825 strictureplasties.38 Indications for surgery included recurrent small bowel obstruction (92%), weight loss, chronic pain, fistula, narcotic dependence, and gastrointestinal bleeding. Ninety percent of the strictures were less than 10 cm in length. Stricture sites included jejuno-ileal, duodenal, and anastomotic sites. Fifty-six patients underwent only strictureplasty; the remaining patients underwent strictureplasty along with bowel resection. Heineke–Mikulicz and Finney were the most common method of strictureplasty (85 and 13%, respectively).38 Tichansky et al38 reported 74 complications in 66 patients for an overall morbidity of 13%. Approximately 25% of patients required reoperation and the overall recurrence rate was 25.5% requiring an additional 132 procedures. From this meta-analysis, Tichansky et al concluded that strictureplasty for Crohn's disease is a safe surgical option.38 In 2004, Roy and Kumar reviewed the more recent literature on strictureplasty and found the morbidity and recurrence rates to be similar to this meta-analysis.8

ANASTOMOTIC STRICTURE DISEASE

Surgical Treatment

RESECTION

Crohn's disease is often treated with ileocolic resection, as the ileum is the segment of intestine most often affected. Most patients will have symptomatic improvement of their disease after ileocolic resection; however, this is not curative and recurrence of disease is common. This is often in the form of stricture at the anastomotic site regardless of whether the original anastomosis was performed hand-sewn or stapled. Endoscopically, up to 72% of patients will develop recurrence at the anastomosis site within one year of surgery.39

Many of these patients require reoperation, usually involving reresection; however, many of these patients will develop multiple recurrences and require multiple surgeries. As discussed earlier, the potential for developing short-bowel syndrome increases with each resection. This fear has led again to the use of bowel-sparing techniques for anastomotic recurrences.

STRICTUREPLASTY

Anastomotic stricture is the form of recurrence that is most amenable to bowel-sparing surgery, namely strictureplasty. The indications for anastomotic strictureplasty are the same as for strictureplasty in other regions and the contraindications also mirror the ones for strictureplasty in other regions. The choice of strictureplasty in this region is between Heineke–Mikulicz and Finney, with Heineke–Mikulicz being the most commonly performed.40 Technically, the strictureplasty is performed in the standard fashion depending on the choice of procedure. Some differences in this region include the need to adequately mobilize the colon to facilitate a tension-free closure.40 The surgeon should also be prepared for an extensive lysis of adhesions as the patients have had previous surgery in the same location. Caution must be employed when using electrocautery in this region as the patient has had a previous anastomosis, possibly with staples. The staples can transmit heat to the tissues40 and a thermal injury may occur. Biopsy of the diseased segment with frozen section can perhaps be used when strictureplasty is performed to exclude occult malignancy.

The experience with anastomotic strictureplasty is limited relative to small bowel disease as the application to anastomotic strictures is more recent and the incidence of the disease in this region is not as common. Tjandra and Fazio40 reported a series of 22 patients with no mortalities, no major morbidities, and a recurrence rate of 9%. Yamamoto and Keighley41 reported 42 patients who underwent anastomotic strictureplasty with no mortalities, no major complications, 21% minor complications, with a 57% recurrence rate. The high recurrence rate is consistent with a long median follow-up of 99 months.41 This report along with others42 demonstrates that strictureplasty at anastomotic sites is a safe and efficacious procedure and should be considered an option in any patient who is a candidate.

STRICTUREPLASTY TECHNIQUES

The technical aspects of three types of strictureplasties will be discussed here including Heineke–Mikulicz, Finney, and the side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty. The most important variable in the decision of which specific procedure to perform is the length of the stricture. Short-length strictures are best treated with Heineke–Mikulicz. Intermediate length strictures (10 to 20 cm) are best treated with the Finney, and long strictures or multiple strictures in an isolated length of bowel should be treated with the side-to-side isoperistaltic procedure described by Michellassi.13 All strictureplasty sites should be marked with a titanium clip for future radiographic evaluation and localization.

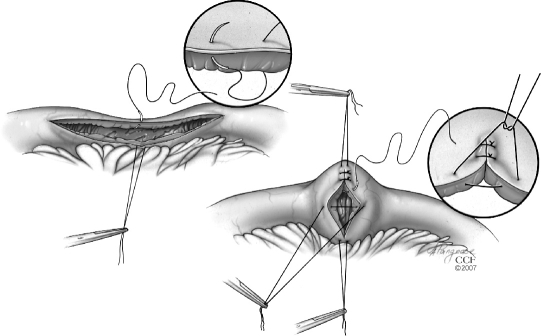

The Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty is performed the same way as the pyloroplasty. A longitudinal enterotomy is made over the stricture on the antimesenteric border of the bowel and is extended 1 to 2 cm onto either side of normal bowel. The enterotomy may be made using the scalpel or cautery. The enterotomy is then closed transversely with interrupted, seromuscular absorbable sutures (Fig. 1). The closure may be performed in one or two layers. Care must be taken to ensure that there is no tension on the closure.

Figure 1.

Heineke–Mikulicz strictureplasty. Reprinted with the permission of The Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2007. All Rights Reserved.

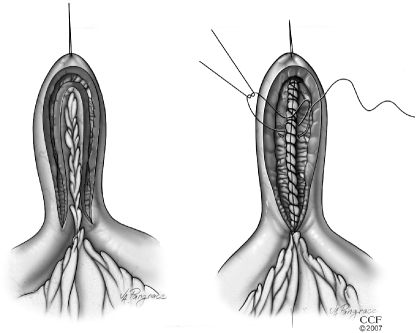

The Finney strictureplasty is performed for intermediate length strictures. First, a stay suture is placed at the midpoint of the stricture (Fig. 2). The enterotomy is made through the stricture as in the Heineke–Mikulicz, again extending 1 to 2 cm onto normal bowel, then the strictured segment is folded onto itself to form a U-shape. Another stay suture is placed on the normal side of the bowel to hold the U-shape in place. The posterior edges are then sutured in a continuous fashion using an absorbable suture. The anterior edges are then closed with an absorbable suture in an interrupted fashion.

Figure 2.

Finney strictureplasty. Reprinted with the permission of The Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2007. All Rights Reserved.

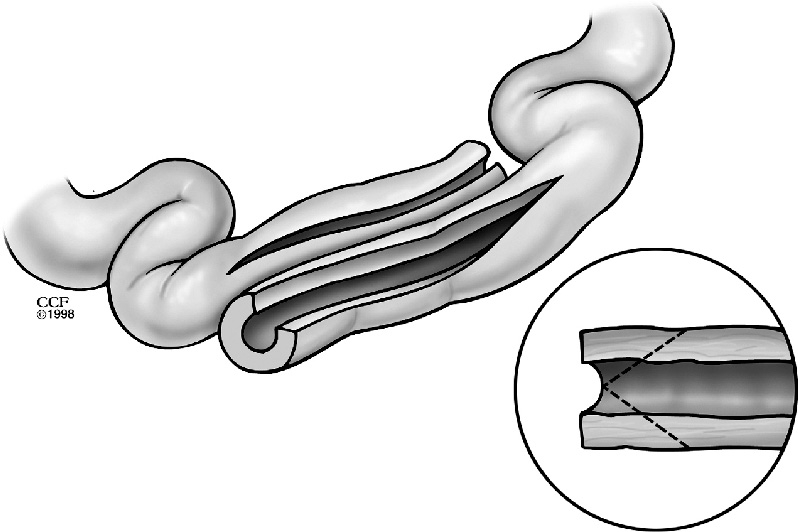

The side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty, as described by Michelassi,13 is performed for longer length strictures, usually greater than 20 to 25 cm. In this procedure, the length of strictured bowel is lifted up and the mesentery for this region is divided at the midpoint. Next, the diseased bowel is divided between atraumatic bowel clamps at the midpoint of the stricture. The proximal end of the cut bowel is brought over the distal end in a side-to-side fashion. The two loops of bowel are then approximated with a single layer of interrupted nonabsorbable sutures. Next, the enterotomy is made longitudinally for the length of the stricture. The ends of the bowel are spatulated to avoid blind ends. Next, an inner layer of running, full-thickness absorbable sutures are placed and continued anteriorly as a running Connell stitch. This anterior layer is then followed by a layer of interrupted, nonabsorbable seromuscular sutures (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty. Reprinted with the permission of The Cleveland Clinic Center for Medical Art & Photography © 2007. All Rights Reserved.

As described earlier, many variations of the above procedures have been described. These variations usually involve either the use of stapling devices or combining parts of each procedure. Despite these innovations, the three procedures described here remain the most commonly used and the most commonly studied. Stapled side-to-side functional end-to-end strictureplasty is probably the most common variation. Indications we described earlier in this text and the procedure should be familiar to all surgeons.

In all types of strictureplasties, postoperative hemorrhage is a concern. Ozuner and Fazio43 reported a postoperative hemorrhage rate of 9.3%. In their series, all patients were managed nonoperatively with close observation and transfusion except for two patients who were treated with angiography. Prior to closing, adequate hemostasis should be attempted; however, slight oozing is expected in these procedures. Despite this concern of hemorrhage, strictureplasty remains a safe procedure.43

CARCINOMA AND STRICTUREPLASTY

Despite the overall success of strictureplasty for Crohn's disease strictures, one concern that has been highlighted in recent years is that of cancer at the strictureplasty site. Marchetti et al44 reported the first case of carcinoma at a strictureplasty site in 1996. Since then, a few more cases have been reported at strictureplasty sites.45,46 The concern stems over the point of leaving known diseased bowel in the form of strictureplasty rather than the traditional resection, as this diseased bowel may be the point of origin for carcinoma. The relative risk of developing small bowel carcinoma in Crohn's disease patients is greater than the general population;46 however, the reported incidence of carcinoma at a strictureplasty site is quite low. In 1996, ~1500 cases of strictureplasty were reported with only two cases of carcinoma reported at the strictureplasty site.46 This may change as the follow-up periods for these patients increases to decades rather than years, but currently there is no indication that strictureplasty should not be performed on these patients. Patients should have biopsies with frozen sections performed on proposed sites of strictureplasty.

CONCLUSION

Strictureplasty in patients with Crohn's disease is an option in the colorectal surgeon's armamentarium for fibrostenotic obstructive disease. The procedure, regardless which one specifically, carries significant morbidity and therefore should be carefully chosen for optimal results. Strictureplasty should not be viewed as a replacement to bowel resection in Crohn's disease, but rather as a complement. This being said, strictureplasty is an excellent procedure to reduce the risk of developing short-bowel syndrome and its associated complications.

REFERENCES

- 1.Crohn B B, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer G D. Regional ileitis: a pathologic and clinical entity. JAMA. 1984;251:73–79. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(52)90025-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Del Gaudio A, Panettiere P, Marchetti L, Accorsi D, Fuzzi N. The impact of genetics on Crohn's disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:784–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snook J. Are the inflammatory bowel diseases autoimmune disorders? Gut. 1990;31:961–963. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.9.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirsner J B, Shorter R G. Recent developments in nonspecific inflammatory bowel disease (second of two parts) N Engl J Med. 1982;306:837–848. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198204083061404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nunes G C, Ahlquist R E. Increasing incidence of Crohn's disease. Am J Surg. 1983;145:578–581. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ricart E, Panaccione R, Loftus E V, Tremaine W J, Sandborn W J. Infliximab for Crohn's disease in clinical practice at the Mayo Clinic: the first 100 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:722–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whelan G, Farmer R G, Fazio V W, Goormastic M. Recurrence after surgery in Crohn's disease. Relationship to location of disease (clinical pattern) and surgical indication. Gastroenterology. 1985;88:1826–1833. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roy P, Kumar D. Strictureplasty. Br J Surg. 2004;91:1428–1437. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katariya R N, Sood S, Rao P G, Rao P L. Stricture-plasty for tubercular strictures of the gastro-intestinal tract. Br J Surg. 1977;64:496–498. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800640713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee E C, Papaioannou N. Minimal surgery for chronic obstruction in patients with extensive or universal Crohn's disease. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1982;64:229–233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erkelens G W, Deventer S J van. Endoscopic treatment of strictures in Crohn's disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2004;18:201–207. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Couckuyt H, Gevers A M, Coremans G, et al. Efficacy and safety of hydrostatic balloon dilation of ileocolonic Crohn's strictures: a prospective longterm analysis. Gut. 1995;36:577–580. doi: 10.1136/gut.36.4.577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michelassi F. Side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty for multiple Crohn's strictures. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:345–349. doi: 10.1007/BF02049480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strong S A. Bowel-sparing techniques. Colorectal Dis. 2001;3(s2):47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nugent F W, Roy M A. Duodenal Crohn's disease: an analysis of 89 cases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Murray J J, Schoetz D J, Jr, Nugent F W, Coller J A, Veidenheimer M C. Surgical management of Crohn's disease involving the duodenum. Am J Surg. 1984;147:58–65. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(84)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farmer R G, Hawk W A, Turnbull R B. Crohn's disease of the duodenum (transmural duodenitis): clinical manifestations. Report of 11 cases. Am J Dig Dis. 1972;17:191–198. doi: 10.1007/BF02232289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross T M, Fazio V W, Farmer R G. Long-term results of surgical treatment for Crohn's disease of the duodenum. Ann Surg. 1983;197:399–406. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198304000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Worsey M J, Hull T, Ryland L, Fazio V. Strictureplasty is an effective option in the operative management of duodenal Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:596–600. doi: 10.1007/BF02234132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamamoto T, Bain I M, Connolly A B, Allan R N, Keighley M RB. Outcome of strictureplasty for duodenal Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1999;86:259–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundaram A, Koutkia P, Apovian C M. Nutritional management of short bowel syndrome in adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;34:207–220. doi: 10.1097/00004836-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson J S, Langnas A N, Pinch L W, Kaufman S, Quigley E M, Vanderhoof J A. Surgical approach to short-bowel syndrome. Ann Surg. 1995;222:600–607. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199522240-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fazio V W, Tjandra J J, Lavery I C, Church J M, Milsom J W, Oakley J R. Long-term follow-up of strictureplasty in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:355–361. doi: 10.1007/BF02053938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spencer M P, Nelson H, Wolff B G, Dozois R R. Strictureplasty for obstructive Crohn's disease: the Mayo experience. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61609-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Futami K, Arima S. Role of strictureplasty in surgical treatment of Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:35–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02990577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Michelassi F, Hurst R D, Melis M, et al. Side-to-side isoperistaltic strictureplasty in extensive Crohn's disease, a prospective longitudinal study. Ann Surg. 2000;232:401–408. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bufo A J, Feldman S, Daniels G A, Lieberman R C. Stapled strictureplasty for Crohn's disease. A new technique. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:664–667. doi: 10.1007/BF02054131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deutsch A A, Stern H S. Stapler strictureplasty for Crohn's disease. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1989;169:458–460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sasaki I, Shibata C, Funayama Y, et al. New reconstructive procedure after intestinal resection for Crohn's disease: modified side-to-side isoperistaltic anastomosis with double Heineke-Mikulicz procedure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:940–943. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0517-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Serra J, Cohen Z, McLeod R S. Natural history of strictureplasty in Crohn's disease: 9-year experience. Can J Surg. 1995;38:481–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamamoto T, Bain I M, Allan R N, Keighley M R. An audit of strictureplasty for small-bowel Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1999;42:797–803. doi: 10.1007/BF02236939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hurst R D, Michelassi M D. Strictureplasty for Crohn's disease: techniques and long-term results. World J Surg. 1998;22:359–363. doi: 10.1007/s002689900397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tonelli F, Ficari F. Strictureplasty in Crohn's disease. Surgical option. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:920–926. doi: 10.1007/BF02237351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietz D W, Laureti S, Strong S A, et al. Safety and longterm efficacy of stricture in 314 patients with obstructing small bowel Crohn's disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:330–337. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00775-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Futami K, Arima S. Role of strictureplasty in surgical treatment of Crohn's disease. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:35–39. doi: 10.1007/BF02990577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fearnhead N S, Chowdhury R, Box B, George B D, Jewell D P, Mortensen N J. Long-term follow-up of strictureplasty for Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 2006;93:475–482. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sayfan J, Wilson D A, Alexander-Williams J. Recurrence after strictureplasty or resection for Crohn's disease. Br J Surg. 1989;76:335–338. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800760406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tichansky D, Cagir B, Yoo E, Marcus S M, Fry R D. Strictureplasty for Crohn's disease: meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:911–918. doi: 10.1007/BF02237350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, et al. Natural history of recurrent Crohn's disease at the ileocolonic anastomosis after curative surgery. Gut. 1984;25:665–672. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.6.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tjandra J J, Fazio V W. Strictureplasty for ileocolic anastomotic strictures in Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:1099–1104. doi: 10.1007/BF02052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto T, Keighley M RB. Long-term results of strictureplasty for ileocolonic anastomotic recurrence in Crohn's disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 1999;3:555–560. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80112-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sharif H, Alexander-Williams J. Strictureplasty for ileo-colic anastomotic strictures in Crohn's disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1991;6:214–216. doi: 10.1007/BF00341394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozuner G, Fazio V W. Management of gastrointestinal bleeding after strictureplasty for Crohn's disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:297–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02055607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marchetti F, Fazio V W, Ozuner G. Adenocarcinoma arising from a strictureplasty site in Crohn's disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1315–1321. doi: 10.1007/BF02055130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jaskowiak N T, Michelassi F. Adenocarcinoma at a strictureplasty site in Crohn's disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:284–287. doi: 10.1007/BF02234306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menon A M, Mirza A H, Moolla S, Morton D G. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel arising from a previous strictureplasty for Crohn's disease: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:257–259. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0771-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]