ABSTRACT

The benign serrated architecture of the hyperplastic polyp has now been recognized in morphologically similar lesions with potential for transformation to colorectal carcinoma: the sessile serrated adenoma (SSA), traditional serrated adenoma (TSA), and mixed polyp. These represent a group of serrated polyps with potential to evolve into colorectal cancer through a different molecular pathway than the traditional adenoma–carcinoma sequence, called the serrated pathway. Genetic characteristics involve a defect in apoptosis caused by BRAF and K-ras mutations that create distinct histologic characteristics of atypia in serrated architectural distortion of the crypts. An evidence-based algorithm for the clinical management of this polyp has yet to be determined. Current recommendations suggest these lesions be managed similar to conventional adenomas. The histology of serrated polyps is reviewed, as well as the common characteristics, and implications for treatment and surveillance.

Keywords: Hyperplastic polyp, sessile serrated adenoma, traditional serrated adenoma, mixed polyp, management

Serrated polyp of the large intestine, until recently, was recognized as a common benign lesion, with the small innocuous hyperplastic polyp (HP) as the prototype. Hyperplastic polyps are nondysplastic, have little potential for malignant transformation,1,2 and are considered distinct from adenomas. Recent evidence shows serrated variants similar in morphology to HP, but with malignant potential. Reports of adenocarcinoma of the colon arising from polyps with serrated configuration allude to such variants.3,4 Others have shown that over half of patients with the serrated polyp syndrome (numerous large serrated polyps) have synchronous colon cancers, indicating that giant serrated lesions are precursors to cancer.5 A new category of serrated polyps is now recognized and is biologically different from hyperplastic polyps. These are called serrated adenomas, and include traditional serrated adenoma (TSA), mixed polyp, and sessile serrated adenoma (SSA)— all of which have malignant potential without the villous architecture of classic adenoma.

The majority of colon and rectal cancers are not hereditary, and are defined as sporadic. Up to 80% of sporadic colon and rectal cancers are caused by a sequence of genetic mechanisms called the adenoma–carcinoma sequence, which involves the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene.6,7,8 The serrated pathway to colorectal cancer differs from the classical adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) adenoma–carcinoma sequence. It involves different mutations, namely the v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) and KRAS mutations, creating an architecturally distinct serrated precursor to colon cancer from adenoma. Colon cancer arising from the serrated pathway is not as common, but still accounts for up to 20% of sporadic colorectal cancers.

The three variants of serrated adenomas have subtle architectural differences, but all have carcinogenic potential. Fengolio-Preiser was the first to identify serrated polyps with dysplastic histopathology, specifically the traditional serrated adenoma and mixed polyp.9 The TSA can contain both low- and high-grade dysplasia of the crypt surface epithelium. The mixed serrated polyp contains a combination of serrated architecture seen in HP, but with associated dysplasia characteristic of adenoma. SSA is the most recently identified variant of serrated adenoma, described by Torlakovic et al in 2003.10 It is characterized by morphologic characteristics that lie between the classic hyperplastic polyp and the traditional serrated polyp. It maintains the sessile configuration of HP, but has crypt dilation at the base, branching, and lateral growth along the muscularis mucosa. These features are nondysplastic because there is no evidence of cellular hyperproliferation; this has elicited confusion in recognizing its mutagenic potential. However, SSA has recently been recognized as a precursor to dysplastic serrated adenoma and adenocarcinoma.11 This is significant because SSA are the most prevalent of the serrated adenomas.12 The biological and pathological features of these polyps are just beginning to be characterized, and the natural history of disease progression not well defined. The genetic basis for transformation from SSA to cancer is through the serrated pathway. Understanding this pathway provides insight into the clinical significance of SSA and provides evidence supporting treatment, and surveillance for patients with these lesions.13,14,15

THE SERRATED ADENOMA PATHWAY

The serrated adenoma pathway is distinct from the adenoma–carcinoma sequence in colorectal cancer. In the serrated pathway, there are two arms that involve acquired genetic mutations, BRAF and KRAS. The BRAF oncogene is the most commonly acquired genetic mutation in this pathway and is associated with high CpG-island methylation phenotype (CIMP-H) and high microsatellite instability (MSI-H).16,17 In this pathway, microsatellite instability is due to hypermethylation of the promoter region in MLH1 and is distinctly different from the hereditary mutation of this found in hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer syndromes. The BRAF mutation is most strongly associated with SSA and mixed serrated polyp, each of which have been shown to have loss of expression of MLH1,18 and is found in approximately two thirds of serrated adenomas. Clinically, patients with serrated adenomas in this arm of the pathway are predominantly middle-aged women who manifest with right-sided colon lesions. Morphologically, these lesions are pale, flat, and exhibit an architectural pattern of serration at the base of dilated crypts.14

The second less-common pathway involves the KRAS mutation, which is found in 30% of serrated adenomas, and is more commonly associated with the traditional serrated adenoma subtype. This pathway exhibits low levels of methylation and microsatellite instability (MSI-L). These lesions are more commonly found in the distal colon.19 Architectural features are similar to adenomatous polyps and exhibit absent or less-pronounced crypt serration.

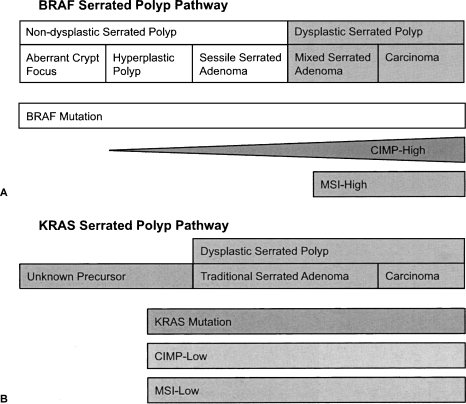

The relationship between the benign hyperplastic polyp as a precursor to serrated adenoma and colorectal cancer is unclear. Some have postulated that in the BRAF pathway, transformation occurs from an aberrant crypt focus to hyperplastic polyp, to SSA with degeneration into dysplastic serrated adenoma and adenocarcinoma.19 However, the precursor in the KRAS pathway has yet to be determined. The BRAF and KRAS serrated polyp pathways depict this progression, as illustrated in Fig. 1.20

Figure 1.

(A) The v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1 (BRAF) serrated polyp pathway begins with an aberrant crypt focus. As the BRAF mutation accumulates, the polyp evolves to a sessile serrated adenoma, a nondysplastic precursor to serrated adenoma and cancer. These lesions are characteristically microsatellite instability H (MSI-H) and CpG-island methylation phenotype H (CIMP-H) as they evolve into cancer. (B) The v-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) polyp pathway begins with an unknown precursor. As the KRAS mutation accumulates, dysplastic serrated polyp evolves with CIM) low, MSI low characteristics. Modified from O'Brien.20

Diagnostic Features of Serrated Polyps

Hyperplastic polyp and serrated adenoma have overlapping architectural features of saw-tooth pattern with subtle variations. The predominance of location and size also varies and is reviewed below.

HYPERPLASTIC POLYP

The benign hyperplastic polyp accounts for 80 to 90% of serrated polyps. It lacks dysplastic architectural distortion and mutagenic potential for transformation to cancer, and does not represent risk for developing neoplasia.21,22 Endoscopic characteristics favor a small (< 3 to 5 mm) sessile lesion that is pale, often multiple, and located predominantly in the left colon at the rectosigmoid area, usually in older patients.1 It is the most common polyp encountered on flexible sigmoidoscopy. Pathophysiology implicates a failure in epithelial cellular apoptosis, or programmed cell death, such that cells mature normally, but heap up on the mucosal surface appearing as small sessile elevations. Microscopic appearance reveals cellular crowding with serration in the upper to mid crypt, and a predominance of mature goblet cells. Chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine and magnification reveals a star-like pit pattern that differentiates it from the irregular surface grove pattern of the adenomatous polyp.23 Narrow band imaging reveals a honeycomb capillary pattern characteristic of this benign lesion.23 Management of HP involves at most confirmation by biopsy on colonoscopy.

SESSILE SERRATED ADENOMA

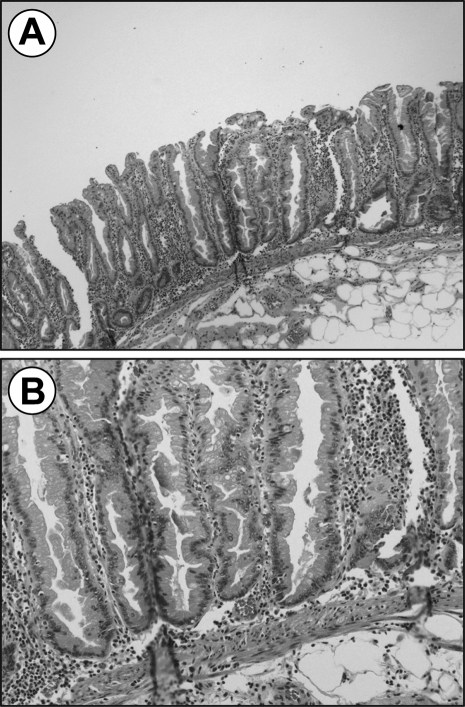

SSA is recognized as the most common of the serrated adenomas accounting for 15 to 20% serrated polyps compared with TSA, which is less than 1%. SSA has been difficult to diagnose due to the absence of dysplasia, which traditionally refers to abnormal cell growth on histology. These polyps display alterations of the proliferation zone, producing characteristic “architectural” changes noted by abnormalities in the lower crypts. Microscopic appearance reveals dilation of the crypts at the base, often with lateral extension parallel to the muscularis mucosae, or herniation through it giving the appearance of invasive tumor (Fig. 2).24 Serration is also often seen at the base of the crypts. The proliferation zone is asymmetric with mitoses found in the upper portion of the crypts. Although atypia may be seen, it is not a diagnostic criteria, as this lesion is considered to be primarily nondysplastic. Even so, SSA has the potential to evolve into dysplastic serrated adenoma, and is therefore considered an aggressive lesion.

Figure 2.

The architectural features of sessile serrated adenoma are shown here in (A) low power field and (B) high power field illustrating the branching dilated crypts at the lower base parallel to the muscularis mucosa creating an inverted T or L shape.

Endoscopic appearance of SSA is typically a pale, large, sessile lesion that rests on the crest of the mucosal folds. A SSA is predominantly found in the proximal colon of middle-aged women and grows to larger sizes than other serrated adenomas. It is strongly associated with the BRAF mutation that is MSI-H and CIMP-H, and considered to be a precursor to dysplastic serrated adenomas and serrated adenocarcinoma.24 The time frame for progression from dysplasia to cancer is unknown. When a SSA is seen in conjunction with carcinoma, there is typically a transition zone of adenomatous epithelium that resembles the villous structure of adenomatous lesions. These lesions are mixed serrated polyps, and may represent the evolution of SSA to dysplasia. Additionally, it has been suggested that here may be some “fusion” of BRAF and KRAS pathways where the accrual of these mutations creates cellular dysplasia and serrations with adenomatous features that overlap with the traditional adenoma pathway to colon cancer.25

TRADITIONAL SERRATED ADENOMA

The TSA is very rare, constituting less than 1% of all colorectal polyps. It is characterized by epithelial dysplasia with serration of the crypt luminal surface and prominent infolding of the epithelium. Other cytological features include central, elongated nuclei, mild pseudostratification, and eosinophilic cytoplasm.24 Gross appearance favors a pedunculated lesion on the left side of the colon that is easily identified on colonoscopy. Variations in gross appearance may overlap with those of adenomatous polyps. It is most strongly associated with KRAS mutation that is MSI-L and CIMP-L.10

MIXED POLYP

The mixed polyp variant displays features of hyperplastic polyp and SSA, and a dysplastic component resembling conventional adenoma. These polyps tend to occur in the right side of the colon, are smaller in size, and show a predominance of BRAF mutation with MSI-H and CIMP-H profile. They may represent a SSA evolving to cytological dysplasia and carcinoma because a mixed serrated and adenomatous transition zone is commonly noted when SSA is found in conjunction with carcinoma.24

The histologic and genetic characteristics of serrated polyps are reviewed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Histologic and Genetic Characteristics of Serrated Polyps

| Polyp | Size | Location | Dysplasia | Malignant Potential | Mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF, v-raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B1; KRAS, v-Ki-ras2 Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog. | |||||

| Hyperplastic polyp | < 5 mm | Distal | No | Minimal | |

| Mixed polyp | > 5 mm | Proximal | Yes | Yes | KRAS |

| Traditional serrated | > 5 mm | Distal | Yes | Yes | KRAS |

| Sessile serrated | > 5 mm | Proximal | No | Yes | BRAF |

Management of Serrated Adenoma

Management of serrated adenomas is inconclusive due to lack of evidence-based data for this new classification of polyps. Furthermore, the natural history of serrated adenoma is not well defined. Although the recurrence rate and rate of progression to carcinoma remain unknown, it is clear that serrated adenomas are a precursor to adenocarcinoma of the colon and rectum. Therefore, it has been suggested that these lesions be managed in a similar way to patients with conventional adenomas.26

The most recent guidelines by the U.S. National Task Force on Colon Cancer recognize the association between the serrated polyp pathway and potentially aggressive lesions such as the SSA, but fall short of making specific recommendations for management. Despite uncertainties about this disease, recommendations for management have been offered.26,27 A far right-sided SSA without evidence of dysplasia should be removed endoscopically if possible with a negative margin. Close surveillance follow-up should be considered (2 to 6 months) to verify complete removal versus evidence of progression to cytologic dysplasia. Once complete removal has been established, subsequent surveillance needs to be individualized based on the endoscopist's judgment and patient risk factors, such as polyp size, number of polyps, personal history of colon or rectal cancer, or family history of colon cancer. Presence of dysplasia on initial or subsequent endoscopic evaluation should prompt consideration for surgical excision based on margin status, surgical risk factors, or patient compliance with follow-up.

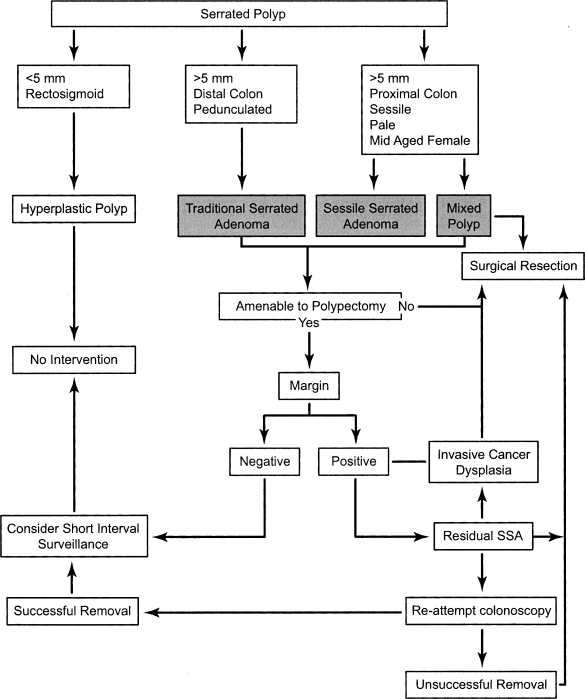

A SSA is less commonly found on the left side or distal colon. In this location, these lesions are typically smaller and are, therefore, more amenable to polypectomy. Similar principles apply to surveillance versus surgical resection based on margin of resection and presence of dysplasia. Figure 3 illustrates an algorithm of suggested management of the serrated poly based on histology, size, common location of presentation, and therapeutic outcome.

Figure 3.

Algorithm suggesting possible management pathways for serrated polyps: hyperplastic polyp, traditional serrated adenoma, sessile serrated adenoma, and mixed polyp.

Diagnostic or therapeutic biopsies must obtain adequate tissue to improve the accuracy of the histologic diagnosis. The diagnostic features differentiating HP from the dysplastic variants are largely architectural, thus superficial biopsies should be avoided. Complete endoscopic resection of SSA may be assisted using the saline lift technique. The margin of SSA may be deep, and invade past the muscularis mucosae. Failure to endoscopically resect this lesion in its entirety maintains cancer risk, and warrants short surveillance interval with repeat therapeutic attempt, or definitive resection. Polyps too large to remove endoscopically or in a difficult position should be surgically removed.

Endoscopic discrimination between nondysplastic HP and SSA versus dysplastic SSA, TSA, and mixed polyp may be improved using adjuncts to visualization of pit and capillary pattern differences. High-definition colonoscopy with the use of indigo carmine and narrow band imaging can help differentiate between the star-like pit pattern and honeycomb capillary pattern of HP versus the irregularly organized pits and elongated and dilated capillary pattern seen in adenoma.28 Use of these adjunct techniques may help in gross determination of a negative margin based on the mucosal pattern surrounding the excision site, or diagnosis of invasive cancer mandating surgical resection.

Discrimination between hyperplastic polyps and SSA has proven to be highly variable, even among gastrointestinal pathologists due to subtle differences in architectural variation and absence of dysplasia in SSA.29 The diagnosis of a hyperplastic polyp larger than 1 cm and located in the right colon represents an atypical presentation and should be revisited by the surgeon and pathologist to determine if this is SSA. An error in diagnosis may have serious implications in providing proper treatment or surveillance for this patient.

SUMMARY

The serrated pathway to colon cancer is a newly identified and clinically significant mechanism by which sporadic colon cancers develop. Variant polyps of the serrated adenoma family have been recognized as precursor lesions with serious mutagenic potential for conversion to cancer, the most common of which is the SSA. Although the natural history of this serrated adenoma is unclear, recognition of its biological potential supports management of this lesion in a similar way to conventional adenomas. Further studies are needed to determine duration of serrated neoplasia progression, and implications for assessment of risk and surveillance for affected individuals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Estrada R G, Spjut H J. Hyperplastic polyps of the large bowel. Am J Surg Pathol. 1980;4:127–133. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198004000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldman H, Ming S, Hickock D F. Nature and significance of hyperplastic polyps of the human colon. Arch Pathol. 1970;89:349–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azimuddin K, Stasik J J, Khubchandani I T, et al. Hyperplastic polyps: “more than meets the eye”? Report of sixteen cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1309–1313. doi: 10.1007/BF02237443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warner A S, Glick M E, Fogt F. Multiple large hyperplastic polyps of the colon coincident with adenocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:123–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeevaratnam P, Cottier D S, Browett P J, et al. Familial giant hyperplastic polyposis predisposing to colorectal cancer: a new hereditary bowel cancer syndrome. J Pathol. 1996;179:20–25. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199605)179:1<20::AID-PATH538>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leggett B A, Devereaux B, Biden K, et al. Hyperplastic polyposis: association with colorectal cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:177–184. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200102000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torlakovic E, Snover D C. Serrated adenomatous polyposis in humans. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:748–755. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogelstein B, Fearon E R, Hamilton S R, et al. Genetic alterations during colorectal-tumor development. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:525–532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Longacre T A, Fenoglio-Preiser C M. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 1990;14:524–537. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199006000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Torlakovic E, Skovlund E, Snover D C, Torlakovic G, Nesland J M. Morphologic reappraisal of serrated colorectal polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:65–81. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein N S, Bhanot P, Odish E, Hunter S. Hyperplastic-like colon polyps that preceded microsatellite-unstable adenocarcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:778–796. doi: 10.1309/DRFQ-0WFU-F1G1-3CTK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spring K J, Zhao Z Z, Karamatic R, et al. High prevalence of sessile serrated adenomas with BRAF mutations: a prospective study of patients undergoing colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1400–1407. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jass J R. Serrated route to colorectal cancer: back street or super highway? J Pathol. 2001;193:283–285. doi: 10.1002/1096-9896(200103)193:3<283::AID-PATH799>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jass J R. Hyperplastic-like polyps as precursors of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;119:773–775. doi: 10.1309/UYN7-0N9W-2DVN-9ART. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jass J R, Whitehall V L, Young J, Leggett B A. Emerging concepts in colorectal neoplasia. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:862–876. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan T L, Zhao W, Leung S Y, Yuen S T. BRAF and KRAS mutations in colorectal hyperplastic polyps and serrated adenomas. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4878–4881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koinuma K, Shitoh K, Miyakura Y, et al. Mutations of BRAF are associated with extensive hMLH1 promoter methylation in sporadic colorectal carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2004;108:237–242. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iino H, Jass J R, Simms L A, et al. DNA microsatellite instability in hyperplastic polyps, serrated adenomas, and mixed polyps: a mild mutator pathway for colorectal cancer? J Clin Pathol. 1999;52:5–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Brien M J, Yang S, Mack C, et al. Comparison of microsatellite instability, CpG island methylation phenotype, BRAF and KRAS status in serrated polyps and traditional adenomas indicates separate pathways to distinct colorectal carcinoma end points. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1491–1501. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213313.36306.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Brien M J. Hyperplastic and serrated polyps of the colorectum. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2007;36(4):947–968 vii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bensen S P, Cole B F, Mott L A, et al. Colorectal hyperplastic polyps and risk of recurrence of adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Polyps Prevention Study. Lancet. 1999;354:1873–1874. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04469-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bond J H. Polyp guideline: diagnosis, treatment, and surveillance for patients with colorectal polyps. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3053–3063. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kudo S, Hirota S, Nakajima T, et al. Colorectal tumours and pit pattern. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:880–885. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.10.880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harvey N T, Ruszkiewicz A. Serrated neoplasia of the colorectum. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3792–3798. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i28.3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jass J R, Baker K, Zlobec I, et al. Advanced colorectal polyps with the molecular and morphological features of serrated polyps and adenomas: concept of a ‘fusion’ pathway to colorectal cancer. Histopathology. 2006;49:121–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2006.02466.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snover D C. Serrated polyps of the large intestine. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2005;22:301–308. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snover D C, Jass J R, Fenoglio-Preiser C, Batts K P. Serrated polyps of the large intestine: a morphologic and molecular review of an evolving concept. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:380–391. doi: 10.1309/V2EP-TPLJ-RB3F-GHJL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sano Y, Yoshida S. In: Cohen J, editor. Advanced Digestive Endoscopy: Comprehensive Atlas of High Resolution Endoscopy and Narrowband Imaging. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. Optical chromoendoscopy using NBI during screening colonoscopy: its usefulness and application. pp. 123–131.

- 29.Farris A B, Misdraji J, Srivastava A, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma: challenging discrimination from other serrated colonic polyps. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:30–35. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318093e40a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]