Abstract

Background

Although nearly 2 million people live with HIV in Latin America and the Caribbean, mortality rates after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) have not been well-described.

Methods

5,152 HIV-infected, antiretroviral-naïve adults from clinics in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, and Peru starting HAART during 1996–2007 were included. First-year mortality rates and their association with demographics, regimen, baseline CD4, and clinical stage were assessed.

Results

Overall 1-year mortality rate was 8.3% (95% confidence interval [CI]:7.6–9.1%), although variable across sites: 2.6, 3.7, 6.0, 13.0, 10.8, 3.5, and 9.8% for clinics in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, and Peru, respectively. 80% of deaths occurred within the first 6 months. Median baseline CD4 was 107 cells/μL, ranging from 79 (Peru) to 163 (Argentina). Mortality estimates adjusting for CD4 were similar across sites (1.1–2.8% for CD4=200), except for Haiti, 7.5%, and Honduras, 7.0%. Death was associated with lower CD4 (adjusted hazard ratio [HR] for CD4=200 vs CD4=50 was 0.58; 95% CI:0.40–0.85) and clinical AIDS (HR=3.1; 95% CI:2.1–4.5).

Conclusions

Mortality rates were similar to those reported elsewhere for resource-limited settings. Disease stage at HAART initiation, treatment eligibility criteria, program age, and background mortality rates may explain some variability in prognosis between sites.

Keywords: Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active, Low-Income Population, HIV, South America, Caribbean, Treatment Outcome, Cohort

INTRODUCTION

Although the HIV epidemic in Latin America and the Caribbean has been overshadowed by the more dramatic picture in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia, an estimated 1.9 million people in these countries are living with HIV, comprising 5.7% of all infected persons worldwide [1]. At the end of 2007, approximately 315,000 persons in the region were receiving antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, which represents a notable 72% coverage of those eligible according to current HIV treatment guidelines, in contrast to only 31% in most parts of the developing world [2]. While these numbers represent a remarkable achievement, little is known about the impact of such strategies on HIV-associated mortality in these communities. Multinational collaborations such as ART-CC [3], TAHOD [4] and ART-LINC [5] have allowed assessment of short- and long-term outcomes in resource-rich and -limited settings, but Latin America and the Caribbean have been largely underrepresented, or not represented at all, in these cohort studies.

In 2005, the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA; www.iedea-hiv.org) program was established to develop an international consortium of cohorts collecting high-quality HIV data to address research questions that could not be answered by single cohorts alone. The Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV Research (CCASAnet; www.ccasanet.vanderbilt.edu) collaboration is IeDEA Region 2 and includes sites from seven nations: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, and Peru. Here we report on the first year mortality rates of HIV-infected adults initiating HAART, assess prognostic factors, and discuss potential country-specific issues associated with risk of death at these CCASAnet sites.

METHODS

Participants and Settings

The CCASAnet cohort profile has been described elsewhere [6]. Briefly, the collaboration was set up in 2006 to create and support a network of participating sites in the Caribbean and Central and South America for sharing data related to the epidemiology of HIV and related disorders. The combined sample size currently includes data from 7 sites: Fundación Huesped in Buenos Aires, Argentina (FH-Argentina); Hospital Universitário Clementino Fraga Filho in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (HUCFF-Brazil); Fundación Arriarán in Santiago, Chile (FA-Chile); Le Groupe Haïtien d’Etude du Sarcome de Kaposi et des Infections Opportunistes in Port-au-Prince, Haiti (GHESKIO-Haiti); Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social and Hospital de Especialidades in Tegucigalpa, Honduras (IHSS/HE-Honduras); El Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán in Mexico City, Mexico (INNSZ-Mexico); and Instituto de Medicina Tropical Alexander von Humboldt in Lima, Peru (IMTAvH-Peru).

Data for this study were sent to the central data repository at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA, and checked for errors and inconsistencies. Data audits then were performed at each site by a team from the Vanderbilt Data Coordinating Center (VDCC). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained locally for each participating site as well as for the VDCC. All data were de-identified by local centers prior to being transmitted to the VDCC. The present analysis used available data collected through June 2008 and included antiretroviral-naïve HIV-infected patients prescribed HAART at age 18 years or older.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality within the first year of HAART initiation. Time was measured from the start of HAART and ended at the earliest of the date of death, the date of last follow-up visit, or 365 days after starting HAART. Patients were considered lost to follow-up if their status (alive or dead) 365 days after HAART initiation was not known and if their last visit occurred more than 365 days before the closing date of the database [5]. The closing date was defined separately for each site as the date of the most recent follow-up recorded in the database. Intent-to-continue treatment analysis was used, ignoring changes, interruptions, or termination of treatment.

Data Sources and Measurements

Baseline CD4 count was defined as the measurement closest to HAART initiation but not more than 6 months prior to, or 7 days after, the date of HAART start. Baseline HIV-1 plasma viral load (PVL) was defined as the pre-HAART measurement closest to, but not more than 6 months prior to, HAART initiation. Baseline weight and hemoglobin were defined as the measurements closest to HAART initiation within +/− 30 days. HAART was defined as protease inhibitor (PI)-based (one ritonavir-boosted or unboosted PI plus two nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors [NRTI]), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase (NNRTI)-based (one NNRTI plus two NRTIs), or other combinations (including triple NRTI regimens and any other regimen containing a minimum of three drugs). Results were similar when 20 patients on non-standard HAART regimens were excluded (data not shown). Clinical stage of disease was defined as AIDS (WHO stage 4, CDC stage C, or 1986 CDC stage 4), non-AIDS, or unknown.

Statistical Analysis

Kaplan-Meier estimates were used to compute mortality and mortality/loss-to-follow-up probabilities per site during the first year. The relationship between time to death and baseline variables was assessed using Cox proportional hazards models applied separately for each site. The primary multivariable analyses only included baseline predictors routinely collected at all sites. Secondary, site-specific multivariable analyses included other routinely collected predictors with >50% non-missing data. In the multivariable analyses, missing values of baseline predictors were accounted for using multiple imputation techniques applied separately within each site [7]. Specifically, the predictive distributions of variables with missing data conditional on all other variables in the model (including follow-up time, death, and an interaction between follow-up time and death) were estimated using multiple logistic or linear regression for each site; values for the missing variables were drawn from these predictive distributions; site-specific multivariable Cox analyses were performed using these imputed values; and the process was repeated 10 times for each site, with the variation between replications incorporated in the resulting 95% confidence intervals. Multiple imputation accounts for differences of other observed characteristics between those who are and who are not missing data. CD4 count and year of HAART initiation were included in models as continuous variables and expanded using restricted cubic splines to avoid linearity assumptions [8]. The combined hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were computed based on the results of the site-specific hazard ratios using the meta-analysis approach of DerSimonian and Laird, a random effects method which makes no assumption regarding proportional hazards across sites [9, 10]. Baseline characteristics of those alive, lost, and dead at the end of one year were compared using rank sum and chi-square tests. Cox proportional hazards models examined the association between date of HAART initiation and loss to follow-up, censoring those individuals who died and not including those who started HAART within two years of the database close date. Site-specific mortality rates were also estimated accounting for baseline differences between those lost and remaining in the study using inverse probability weighted methods [11] and averaging across multiple imputations. All analyses were performed using R statistical software, version 2.4.1 (available at http://www.r-project.org). Analysis scripts are available at http://ccasanet.vanderbilt.edu/links.php.

RESULTS

Data sources and patient characteristics

A total of 5,152 antiretroviral therapy-naïve patients who initiated HAART were included in this study: 794 (15%) from FH-Argentina, 522 (10%) from HUCFF-Brazil, 547 (11%) from FA-Chile, 1672 (32%) from GHESKIO-Haiti, 328 (6%) from IHSS/HE-Honduras, 416 (8%) from INNSZ-Mexico, and 873 (17%) from IMTAvH-Peru. Patient characteristics at HAART initiation are summarized by site in Table 1. Across all sites, 35% were female, ranging from 53% females in GHESKIO-Haiti to 13% females in INNSZ-Mexico and FA-Chile. The median age at HAART initiation was approximately 37 years at all sites. Likely routes of HIV infection varied. FA-Chile and INNSZ-Mexico had the highest rates of men who have sex with men (70 and 64%, respectively), whereas FH-Argentina was the only site with a substantial percentage of individuals with history of IDU (13%), and the likely route of infection was not documented for subjects at GHESKIO-Haiti.

Table 1.

Summary of Patient Characteristics at HAART Initiation

| FH-Argentina (n=794) |

HUCFF-Brazil (n=522) |

FA-Chile (n=547) |

GHESKIO-Haiti (n=1672) |

IHSS/HE- Honduras y(n=328) |

INNSZ-Mexico (n=416) |

IMTAvH-Peru (n=873) |

Combined (n=5152) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | 233 (29.3%) | 175 (33.5%) | 70 (12.8%) | 893 (53.4%) | 129 (39.3%) | 52 (12.5%) | 260 (29.8%) | 1812 (35.2%) |

| Age | 35 (30, 43)a | 37 (32, 45) | 36 (30, 42) | 39 (33, 45) | 37 (31, 41) | 35 (29, 42) | 34 (28, 41) | 37 (31, 43) |

| Route of Infection | ||||||||

| Missing | 214 (27%) | 170 (32.6%) | 6 (1.1%) | 1672 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (0.7%) | 2068 (40.1%) |

| Heterosexual | 278 (47.9%)b | 219 (62.2%) | 161 (29.8%) | - | 327 (99.7%)c | 149 (35.8%) | 594 (68.5%) | 1728 (56%)c |

| IVDU | 77 (13.3%) | 7 (2%) | 2 (0.4%) | - | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 87 (2.8%) |

| MSM | 222 (38.3%) | 106 (30.1%) | 378 (69.9%) | - | 0 (0%) | 264 (63.5%) | 272 (31.4%) | 1242 (40.3%) |

| Other | 3 (0.5%) | 20 (5.7%) | 0 (0%) | - | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.7%) | 1 (0.1%) | 27 (0.9%) |

| Clinical Stage | ||||||||

| Missing | 4 (0.4%) | 160 (25.4%) | 2 (0.3%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (2.2%) | 12 (2.1%) | 39 (2.9%) | 227 (4.6%) |

| not AIDS | 541 (68.5%) | 95 (26.2%) | 302 (55.4%) | 954 (57.1%) | 189 (59.4%) | 226 (55.9%) | 312 (37.4%) | 2619 (53.2%) |

| AIDS | 249 (31.5%) | 267 (73.8%)d | 243 (44.6%) | 718 (42.9%) | 129 (40.6%) | 178 (44.1%) | 522 (62.6%) | 2306 (46.8%)d |

| CD4 (cells/μL) | 163 (55, 250) | 153 (53, 240) | 116 (32, 193) | 102 (37, 191) | 105 (55, 185) | 88 (33, 192) | 79 (32, 166) | 107 (39, 201) |

| Missing | 107 (13.5%) | 190 (36.4%) | 108 (19.7%) | 224 (13.4%) | 68 (20.7%) | 18 (4.3%) | 170 (19.5%) | 885 (17.2%) |

| < 50 | 160 (23.3%) | 80 (24.1%) | 142 (32.3%) | 445 (30.7%) | 49 (18.8%) | 137 (34.4%) | 260 (37%) | 1273 (29.8%) |

| 50–99 | 91 (13.2%) | 51 (15.4%) | 65 (14.8%) | 262 (18.1%) | 76 (29.2%) | 74 (18.6%) | 147 (20.9%) | 766 (18%) |

| 100–199 | 178 (25.9%) | 78 (23.5%) | 133 (30.3%) | 410 (28.3%) | 79 (30.4%) | 96 (24.1%) | 168 (23.9%) | 1142 (26.8%) |

| 200–349 | 179 (26.1%) | 102 (30.7%) | 91 (20.7%) | 284 (19.6%) | 48 (18.5%) | 84 (21.1%) | 100 (14.2%) | 888 (20.8%) |

| ≥ 350 | 79 (11.5%) | 21 (6.3%) | 8 (1.8%) | 47 (3.2%) | 8 (3.1%) | 7 (1.8%) | 28 (4%) | 198 (4.6%) |

| CD4<200 or AIDS | ||||||||

| Missing | 2 (0.3%) | 59 (11.3%) | 2 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (2.4%) | 1 (0.2%) | 12 (1.4%) | 84 (1.6%) |

| not Advanced | 293 (37%) | 116 (25.1%) | 96 (17.6%) | 347 (21.7%) | 72 (22.5%) | 74 (17.8%) | 132 (15.3%) | 1130 (22.2%) |

| Advanced | 499 (63%) | 347 (74.9%) | 449 (82.4%) | 1310 (78.3%) | 248 (77.5%) | 341 (82.2%) | 729 (84.7%) | 3938 (76.1%) |

| HIV-1 RNA (log10) | 5 (4.4, 5.4) | 4.7 (3.6, 5.2) | 5.1 (4.7, 5.5) | - | 5 (4.7, 5) | 4.9 (4.9, 4.9) | 5.2 (4.7, 5.5) | 5 (4.6, 5.4) |

| Missing | 236 (29.7%) | 371 (71.1%) | 162 (29.6%) | 1672 (100%) | 234 (71.3%) | 58 (13.9%) | 383 (43.9%) | 3116 (60.5%) |

| < 10,000 | 208 (37.3%) | 45 (29.8%) | 139 (36.1%) | - | 25 (26.6%) | 267 (74.6%) | 132 (26.9%) | 816 (40.1%) |

| 10,000–99,999 | 76 (13.6%) | 49 (32.5%) | 22 (5.7%) | - | 12 (12.8%) | 15 (4.2%) | 59 (12%) | 233 (11.4%) |

| ≥ 100,000 | 274 (49.1%) | 57 (37.7%) | 224 (58.2%) | - | 57 (60.6%) | 76 (21.2%) | 299 (61%) | 987 (48.5%) |

| Weight (kg) | 65 (58, 74) | 65 (58, 74) | 64 (56, 72) | 53 (46, 60) | 59 (51, 65) | 61 (53, 71) | 57 (50, 64) | 56 (49, 64) |

| Missing | 715 (90.1%) | 399 (76.4%) | 326 (59.6%) | 99 (5.9%) | 95 (29%) | 106 (25.5%) | 217 (24.9%) | 1957 (38%) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 13.7 (11.9, 14.6) | 11.7 (10, 13.7) | 12.3 (10.7, 13.7) | 10 (9, 11) | 12.3 (10.8, 13.5) | 14.1 (11.8, 15.7) | 11.3 (10.1, 12.7) | 11 (9.8, 12.9) |

| Missing | 770 (97%) | 267 (51.1%) | 343 (62.7%) | 541 (32.4%) | 147 (44.8%) | 165 (39.7%) | 696 (79.7%) | 2929 (56.9%) |

| Calendar Year | ||||||||

| 1996–1999 | 6 (0.8%) | 136 (26.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.9%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (0.6%) | 150 (2.9%) |

| 2000–2001 | 43 (5.4%) | 124 (23.8%) | 35 (6.4%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (1.5%) | 3 (0.7%) | 11 (1.3%) | 221 (4.3%) |

| 2002–2003 | 232 (29.2%) | 118 (22.6%) | 290 (53%) | 709 (42.4%) | 104 (31.7%) | 147 (35.3%) | 50 (5.7%) | 1650 (32%) |

| 2004–2005 | 355 (44.7%) | 80 (15.3%) | 222 (40.6%) | 939 (56.2%) | 100 (30.5%) | 161 (38.7%) | 525 (60.1%) | 2382 (46.2%) |

| 2006–2007 | 158 (19.9%) | 64 (12.3%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (1.4%) | 116 (35.4%) | 105 (25.2%) | 282 (32.3%) | 749 (14.5%) |

| Initial Regimen | ||||||||

| NNRTI | 513 (64.6%) | 288 (55.2%) | 510 (93.2%) | 1594 (95.3%) | 315 (96%) | 289 (69.5%) | 806 (92.3%) | 4315 (83.8%) |

| PI | 28 (3.5%) | 167 (32%) | 24 (4.4%) | 15 (0.9%) | 10 (3%) | 16 (3.8%) | 21 (2.4%) | 281 (5.5%) |

| Boosted PI | 205 (25.8%) | 43 (8.2%) | 4 (0.7%) | 7 (0.4%) | 2 (0.6%) | 106 (25.5%) | 37 (4.2%) | 404 (7.8%) |

| Other | 48 (6%) | 24 (4.6%) | 9 (1.6%) | 56 (3.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | 5 (1.2%) | 9 (1%) | 152 (3%) |

Continuous variables are reported as medians (interquartile range).

Percentages are computed using the number of patients with a non-missing value.

IHSS/HE-Honduras did not differentiate between heterosexual and MSM routes of infection. All are listed here as heterosexual.

HUCFF-Brazil classified most patients with CD4<200 as having clinical AIDS.

Across all cohorts, the median CD4 count at HAART initiation was 107 cells/μL (interquartile range [IQR]: 39 to 201), ranging from a high of 163 cells/μL for FH-Argentina to a low of 79 for IMTAvH-Peru. Approximately 47% of subjects had clinical AIDS at HAART initiation, ranging from 74% in HUCFF-Brazil (likely due to over-diagnosis because most patients with CD4<200 were classified as having clinical AIDS at this site) to 32% in FH-Argentina. Defining advanced disease as CD4 count <200 cells/μL or a clinical diagnosis of AIDS, 63% were advanced in FH-Argentina, 75% in HUCFF-Brazil, 82% in FA-Chile, 78% in GHESKIO-Haiti, 77% in IHSS/HE-Honduras, 82% in INNSZ-Mexico, and 85% in IMTAvH-Peru. Median baseline HIV-1 PVL and weight were approximately 100,000 copies/mL (IQR: 40,000 to 250,000) and 56 kg (IQR: 49 to 64), respectively, although both variables were missing for a high percentage of subjects.

Patients initiated HAART as early as June 1996 (HUCFF-Brazil), although the majority (78%) started therapy between 2002 and 2005. It should be noted that year of HAART initiation does not necessarily reflect the year of HAART availability in each particular country. NNRTI-based therapy was the most common initial regimen (84%), although PI- and boosted PI-based regimens were not uncommon in FH-Argentina, HUCFF-Brazil, and INNSZ-Mexico (29%, 40%, and 29%, respectively).

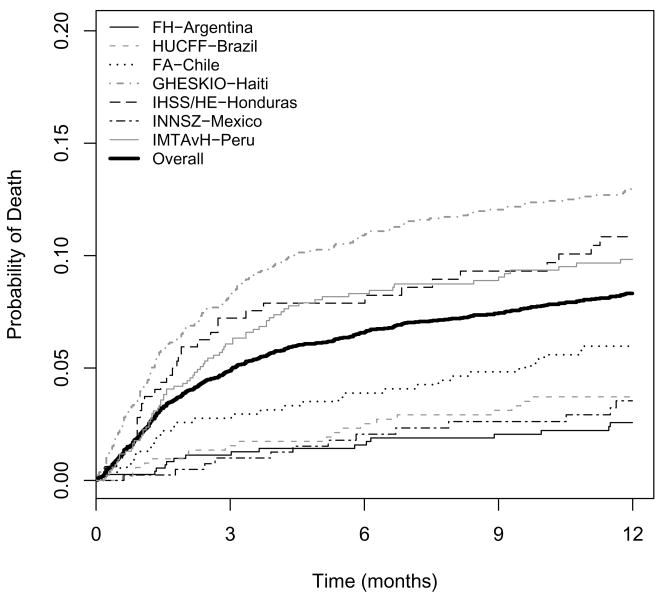

Mortality during the first year

A total of 399 (7.7%) subjects were known to have died within the first year after initiating HAART (Table 2). Of the 399 deaths known to have occurred, 241 (60.4%) were in the first 3 months and 321 (80.5%) were in the first 6 months. Figure 1 shows Kaplan-Meier plots of mortality during the first year. The 1-year probability of death for the combined cohort was 8.3% (95% CI: 7.6 to 9.1%), although this was highly variable across regions: 2.6% (95% CI: 1.6 to 4.1%) for FH-Argentina, 3.7% (95% CI: 2.4 to 5.8%) for HUCFF-Brazil, 6.0% (95% CI: 4.3 to 8.3%) for FA-Chile, 13.0% (95% CI: 11.4 to 14.7%) for GHESKIO-Haiti, 10.8% (95% CI: 7.8 to 14.9%) for IHSS/HE-Honduras, 3.5% (95% CI: 2.1 to 6.0%) for INNSZ-Mexico, and 9.8% (95% CI: 7.9 to 12.2%) for IMTAvH-Peru. The mortality rate was highest during the first months after HAART initiation: 3- and 6-month probabilities of death for the combined cohort were 4.9% (95% CI: 4.3 to 5.5%) and 6.6% (95% CI: 5.9 to 7.3%), respectively. The probability of death between 6 and 12 months was similar for all sites, ranging from 1.0% (FH-Argentina) to 3.0% (IHSS/HE-Honduras).

Table 2.

Number of Patients Lost to Follow-up and Dead during First Year after HAART Initiation

| FH-Argentina (n=794) |

HUCFF-Brazil (n=522) |

FA-Chile (n=547) |

GHESKIO-Haiti (n=1672) |

IHSS/HE- Honduras (n=328) |

INNSZ-Mexico (n=416) |

IMTAvH-Peru (n=873) |

Combined (n=5152) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lost | 135 (17%) | 27 (5.2%) | 20 (3.7%) | 64 (3.8%) | 2 (0.6%) | 22 (5.3%) | 27 (3.1%) | 297 (5.8%) |

| Death within 3 months | 8 (1.0%) | 8 (1.5%) | 15 (2.7%) | 133 (8%) | 23 (7%) | 4 (1.0%) | 50 (5.7%) | 241 (4.7%) |

| Death within 6 months | 11 (1.4%) | 13 (2.5%) | 21 (3.8%) | 176 (10.5%) | 25 (7.6%) | 8 (1.9%) | 67 (7.7%) | 321 (6.2%) |

| Death within 12 months | 17 (2.1%) | 19 (3.6%) | 32 (5.9%) | 208 (12.4%) | 33 (10.1%) | 13 (3.1%) | 77 (8.8%) | 399 (7.7%) |

| Death within 12 months when baseline CD4<50 cells/μL | 11 (6.9%) | 4 (5.0%) | 14 (9.9%) | 84 (18.9%) | 3 (6.1%) | 4 (2.9%) | 44 (16.9%) | 164 (12.9%) |

Figure 1.

Crude mortality rates during the first year after HAART initiation.

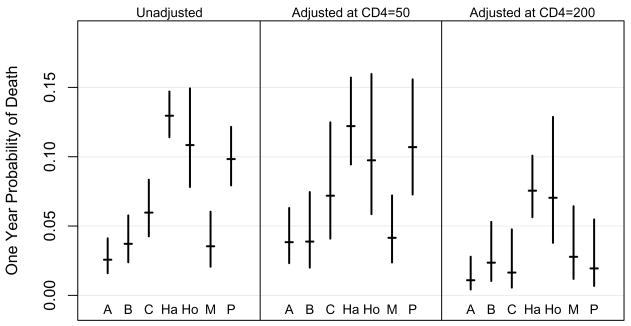

The estimated 1-year mortality rates and confidence intervals for each site at specific baseline CD4 counts are shown in Figure 2. The estimated 1-year mortality probability for an individual starting HAART with CD4 count = 200 cells/μL was quite similar between sites (1.1 to 2.8%), except for GHESKIO-Haiti and IHSS/HE-Honduras, where the mortality rates were estimated as 7.5 and 7.0%, respectively (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Probability and 95% confidence intervals for death at one year (left panel), and estimated for subjects in each cohort initiating HAART with CD4=50 (middle panel), and CD4=200 (right panel). Study sites in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, and Peru are represented by A, B, C, Ha, Ho, M, and P, respectively.

Table 3 shows adjusted hazard ratios for mortality during the first year, for each cohort and combined across cohorts. Higher CD4 count at HAART initiation was associated with a lower hazard of death after adjusting for sex, age, clinical stage, calendar year, and type of regimen. Using CD4 count = 50 cells/μL as a reference, the hazard ratios were 0.79 (95% CI: 0.67 to 0.92), 0.58 (95% CI: 0.40 to 0.85), and 0.43 (95% CI: 0.22 to 0.84) for CD4 counts of 100, 200 and 350 cells/μL, respectively. After adjusting for other variables, the hazard of death was 3.1 times higher for a person with clinical AIDS prior to HAART initiation than a person without (95% CI: 2.1 to 4.5), and older patients were more likely to die within one year of HAART initiation (HR=1.12 per 10 years, 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.25).

Table 3.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) for Mortality in First Year

| FH-Argentina | HUCFF-Brazil | FA-Chile | GHESKIO-Haiti | IHSS/HE- Honduras |

INNSZ-Mexico | IMTAvH-Peru | Combined | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1.47 (0.42, 5.12) | 2.60 (0.75, 8.97) | 0.47 (0.19, 1.14) | 1.04 (0.79, 1.36) | 1.94 (0.86, 4.39) | 1.41 (0.18, 11.1) | 0.92 (0.55, 1.55) | 1.09 (0.79, 1.49) |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.22 (0.73, 2.05) | 1.48 (0.98, 2.24) | 0.97 (0.66, 1.43) | 1.06 (0.91, 1.23) | 1.24 (0.86, 1.77) | 1.42 (0.86, 2.36) | 1.12 (0.89, 1.41) | 1.12 (1.01, 1.25) |

| Clinical AIDS | 9.53 (2.01, 45.19) | 5.41 (0.69, 42.44) | 3.39 (1.27, 9.09) | 2.31 (1.71, 3.12) | 2.09 (1.01, 4.32) | 8.19 (1.59, 42.18) | 4.70 (2.02, 10.94) | 3.10 (2.13, 4.51) |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) | ||||||||

| 100 vs. 50 | 0.73 (0.52, 1.02) | 0.94 (0.71, 1.23) | 0.72 (0.54, 0.95) | 0.73 (0.66, 0.81) | 0.98 (0.77, 1.24) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.62) | 0.57 (0.48, 0.69) | 0.79 (0.67, 0.92) |

| 200 vs. 50 | 0.47 (0.21, 1.06) | 0.86 (0.44, 1.66) | 0.45 (0.23, 0.88) | 0.57 (0.45, 0.73) | 0.94 (0.53, 1.69) | 1.29 (0.52, 3.22) | 0.26 (0.17, 0.41) | 0.58 (0.40, 0.85) |

| 350 vs. 50 | 0.29 (0.08, 1.09) | 0.78 (0.26, 2.30) | 0.27 (0.09, 0.81) | 0.48 (0.28, 0.83) | 0.91 (0.35, 2.37) | 1.53 (0.34, 6.85) | 0.11 (0.05, 0.23) | 0.43 (0.22, 0.84) |

| Year of HAART Initiation | ||||||||

| 2003 (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2004 | 1.12 (0.77, 1.61) | 0.86 (0.71, 1.04) | 0.78 (0.58, 1.05) | 0.69 (0.57, 0.85) | 1.17 (0.94, 1.44) | 1.15 (0.78, 1.68) | 5.82 (2.26, 15.02) | 1.04 (0.64, 1.69) |

| 2005 | 1.25 (0.60, 2.58) | 0.74 (0.50, 1.07) | 0.60 (0.33, 1.10) | 0.48 (0.32, 0.72) | 1.36 (0.88, 2.08) | 1.31 (0.61, 2.83) | 16.89 (3.50, 81.38) | 0.99 (0.52, 1.89) |

| 2006 | 1.39 (0.47, 4.15) | 0.63 (0.36, 1.11) | -- | 0.33 (0.18, 0.61) | 1.58 (0.83, 3.01) | 1.51 (0.48, 4.75) | 7.45 (1.72, 32.15) | -- |

Overall, there were no consistent trends between date of HAART initiation and mortality. At GHESKIO-Haiti, patients initiating HAART in later years had lower CD4 counts (p<0.001) and were more likely to have clinical AIDS (p<0.001) at baseline (data not shown); however, after adjusting for these and the other factors given in Table 3, initiating HAART in later years was associated with improved one-year survival (HR=0.64 per 1-year difference in date of HAART initiation, eg. 2005 vs. 2004, 95% CI: 0.56 to 0.84). In contrast, patients at HUCFF-Brazil and FA-Chile tended to be less immunosuppressed at HAART initiation over time (p=0.16 and 0.007 for CD4 and clinical stage, respectively, for HUCFF-Brazil and p=0.07 and 0.08 for FA-Chile). After adjusting for these and other predictors, there was a trend towards improved survival at HUCFF-Brazil (HR=0.88, 95% CI: 0.71 to 1.10), and FA-Chile (HR=0.79, 95% CI: 0.58 to 1.07).

Multivariable analyses including hemoglobin, weight, and HIV-1 RNA were also performed for sites which routinely collected this data and are shown in Table 4. Higher baseline hemoglobin was associated with a lower risk of mortality for GHESKIO-Haiti, IHSS/HE-Honduras, and INNSZ-Mexico. Higher baseline weight also was predictive of a decreased mortality risk for GHESKIO-Haiti and IMTAvH-Peru, but was not statistically associated with risk of death for IHSS/HE-Honduras or INNSZ-Mexico. Baseline PVL was not an independent predictor of mortality in any of the sites which routinely collected PVL. In FH-Argentina, the hazard of death was 2.5 times higher for subjects with history of IDU.

Table 4.

Adjusted Hazard Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) for Mortality in First Year including routinely collected predictors for each site

| FH-Argentina | HUCFF-Brazil | FA-Chile | GHESKIO-Haiti | IHSS/HE-Honduras | INNSZ-Mexico | IMTAvH-Peru | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 1.27 (0.36, 4.54) | 2.53 (0.73, 8.72) | 0.45 (0.18, 1.11) | 1.58 (1.18, 2.12) | 1.97 (0.83, 4.66) | 2.84 (0.30, 26.98) | 1.42 (0.82, 2.46) |

| Age (per 10 years) | 1.28 (0.75, 2.21) | 1.48 (0.98, 2.24) | 0.95 (0.64, 1.41) | 1.08 (0.93, 1.25) | 1.24 (0.86, 1.78) | 1.65 (0.94, 2.90) | 1.11 (0.89, 1.39) |

| Clinical AIDS | 8.42 (1.79, 39.68) | 5.20 (0.66, 40.80) | 3.02 (1.13, 8.06) | 1.78 (1.31, 2.43) | 1.64 (0.77, 3.52) | 2.26 (0.35, 14.58) | 3.83 (1.62, 9.02) |

| CD4 count (cells/μL) | |||||||

| 100 vs. 50 | 0.71 (0.50, 1.00) | 0.94 (0.71, 1.23) | 0.71 (0.53, 0.95) | 0.79 (0.72, 0.87) | 0.93 (0.73, 1.19) | 1.26 (0.82, 1.93) | 0.65 (0.53, 0.79) |

| 200 vs. 50 | 0.44 (0.19, 1.01) | 0.86 (0.44, 1.66) | 0.44 (0.22, 0.89) | 0.57 (0.45, 0.72) | 0.84 (0.46, 1.53) | 1.75 (0.62, 4.90) | 0.35 (0.22, 0.57) |

| 350 vs. 50 | 0.26 (0.06, 1.02) | 0.78 (0.26, 2.31) | 0.26 (0.08, 0.82) | 0.40 (0.27, 0.58) | 0.75 (0.28, 2.01) | 2.50 (0.45, 13.80) | 0.18 (0.08, 0.39) |

| Year of HAART Initiation | |||||||

| 2003 (ref) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2004 | 1.19 (0.81, 1.75) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.10) | 0.81 (0.71, 1.10) | 0.70 (0.57, 0.85) | 1.18 (0.95, 1.46) | 0.90 (0.57, 1.42) | 4.49 (1.73, 11.62) |

| 2005 | 1.42 (0.66, 3.04) | 0.79 (0.51, 1.22) | 0.65 (0.35, 1.19) | 0.48 (0.32, 0.73) | 1.39 (0.90, 2.14) | 0.82 (0.33, 2.03) | 10.91 (2.25, 52.93) |

| 2006 | 1.69 (0.54, 5.31) | 0.70 (0.36, 1.34) | NA | 0.34 (0.18, 0.62) | 1.64 (0.86, 3.13) | 0.74 (0.19, 2.90) | 5.05 (1.16, 21.96) |

| HIV-1 RNA (per log10) | 0.83 (0.50, 1.37) | NA | 1.38 (0.83, 2.31) | NA | NA | 3.76 (0.93, 15.11) | 1.10 (0.80, 1.51) |

| Weight (per 10 Kg) | NA | NA | NA | 0.62 (0.52, 0.72) | 1.23 (0.86, 1.77) | 0.82 (0.45, 1.49) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.73) |

| Hemoglobin (per g/dL) | NA | NA | NA | 0.88 (0.82, 0.94) | 0.79 (0.65, 0.96) | 0.51 (0.37, 0.70) | NA |

| Injection Drug Use | 2.46 (0.84, 7.17) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

NA: not applicable because this variable was not regularly collected.

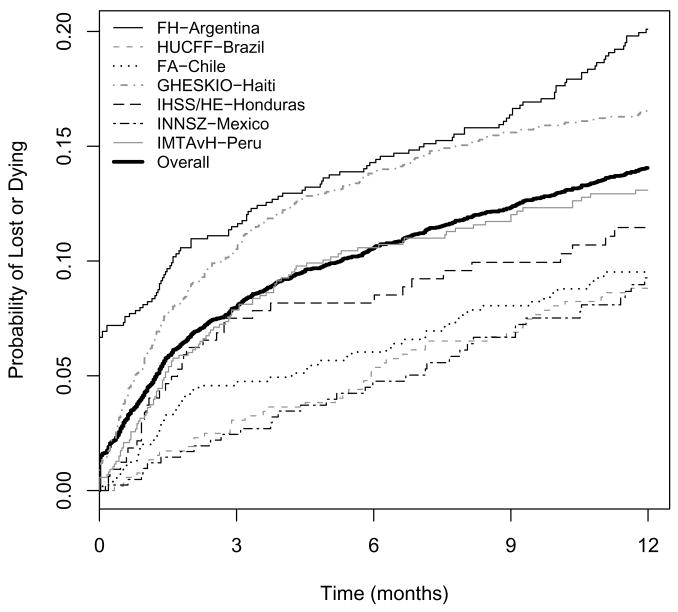

Loss to Follow-up

The percentage of patients lost to follow-up during the first year shown in Table 2 was approximately 6%, ranging from less than 1% (IHSS/HE-Honduras) to 17% (FH-Argentina). The probability of being lost to follow-up or dying during the first year after HAART initiation is shown in Figure 3 for all sites. More than 6% of HAART initiators in FH-Argentina were lost after their first visit. In FH-Argentina, those lost in the first year (n=135) had baseline characteristics more similar to those known to be alive after one year (n=642) than those known to be dead (n=17). The median CD4 count at HAART initiation for those alive, lost, and dead was 162, 190, and 33 cells/μL, respectively (p < 0.001 comparing all three groups, p=0.26 for alive vs lost, and p<0.001 for dead vs lost). The percentage of patients with baseline AIDS for those alive, lost, and dead in FH-Argentina was 30%, 33% and 98% respectively (p<0.001 comparing all three groups, p=0.59 for alive vs lost, and p<0.001 for dead vs lost). For patients who reported IDU as a risk factor for contracting HIV, the percentage of those alive, lost, and dead was 9%, 12%, and 29%, respectively (p=0.03 comparing all three groups, p=0.57 for alive vs. lost, and p=0.12 for dead vs. lost). In FA-Chile, INNSZ-Mexico, and IMTAvH-Peru, those who were lost to follow-up tended to be intermediate between those who died and those who were alive after 1 year in terms of rates of clinical AIDS at HAART initiation, and baseline CD4 count, weight (INNSZ-Mexico and IMTAvH-Peru), and hemoglobin values (INNSZ-Mexico). At GHESKIO-Haiti, those who were lost tended to be more similar at HAART initiation to those who subsequently died during the first year than to those who lived in terms of AIDS (39%, 53%, 66%, for those alive, lost, and dead, respectively), median CD4 count (110, 90, 48 cells/μL), median weight (54, 46, 47 kg), and median hemoglobin (10, 9, 9 g/dL) (p<0.001 comparing all three groups for all four variables; p=0.034, 0.065, <0.001, and <0.001 comparing lost vs alive for AIDS, CD4, weight, and hemoglobin, respectively; and p=0.09, 0.11, 0.72, and 0.63 comparing lost vs dead). In most sites, the rate of loss to follow-up tended to be higher for patients initiating HAART in more recent years. The combined unadjusted hazard of being lost to follow-up during the first year after HAART initiation increased 49% per calendar year (HR=1.49, 95% CI: 1.29 to 1.71).

Figure 3.

Crude rates of loss to follow-up or death during the first year after HAART initiation.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the extent to which loss to follow-up rates might have introduced bias in our 1-year mortality estimates. After accounting for differences in baseline characteristics between those lost and those remaining in care, resulting 1-year mortality estimates were very similar to original estimates: 2.6% (original=2.6%) for FH-Argentina, 3.7% (original=3.7%) for HUCFF-Brazil, 6.0% (6.0%) for FA-Chile, 13.1% (13.0%) for GHESKIO-Haiti, 3.8% (3.5%) for INNSZ-Mexico and 9.9% (9.8%) for IMTAvH-Peru.

DISCUSSION

This is the first multi-cohort study to describe one-year prognosis after HAART initiation in Latin America and the Caribbean. Overall mortality rates were similar to that of lower-income countries with active follow-up, as reported by the ART-LINC Collaboration [5]. However, substantial inter-country differences in mortality rates were observed, suggesting country- and region-specific factors may influence the effectiveness of HAART in these settings.

Consistent with reports from other large collaborations, low CD4 count at therapy initiation and more advanced disease were strong predictors of mortality in the first year [3, 5]. Across sites, cohorts with lower median CD4 count at HAART initiation (GHESKIO-Haiti, IHSS/HE-Honduras, and IMTAvH-Peru) tended to have higher mortality rates than clinics with higher baseline median CD4 count (FH-Argentina, HUCFF-Brazil, and FA-Chile). The one exception was the site in Mexico, where patients presented with low CD4 counts but tended to have high survival rates. Different stages of disease at HAART initiation across sites may be indicative of later presentation for care and/or different criteria for treatment initiation. Later presentation for care may reflect programmatic challenges to detect treatment candidates at earlier stages of disease. In GHESKIO-Haiti, one study showed that lower socioeconomic status and older age, were associated with late access to care [12]. Stigma and discrimination related to HIV/AIDS are reported reasons for refraining from seeking HIV testing among some Latin communities [13]. Different disease stages at HAART initiation also could reflect local treatment guidelines. For example, GHESKIO-Haiti’s treatment program followed contemporary WHO recommendations to treat patients with an AIDS-defining illness or a CD4 count under 200 cells/μL [14], whereas since 1998 HUCFF-Brazil has adopted the strategy of considering treatment for patients with CD4 counts <350 cells/μL.

Sites located in countries with newer treatment programs tended to have patients with higher degrees of immunodeficiency and subsequent mortality. Haiti and Peru began providing free ARV treatment to HIV-infected patients in 2003 and 2004, respectively, in contrast to Brazil and Argentina, where free ARV therapy was offered as early as 1996 and 1997, respectively. Age of program, in turn, may be a proxy for infra-structure development, drug procurement and delivery systems, waiting time and quality of clinical care [15]. Indeed, the probability of death in the first year after HAART initiation tended to be lower for those starting HAART in later years in HUCFF-Brazil, FA-Chile, and GHESKIO-Haiti. Observed trends at HUCFF-Brazil and FA-Chile suggest that HAART has been initiated at less-advanced disease stages in more recent years. In contrast, the opposite was observed in GHESKIO-Haiti, where patients starting HAART in later years tended to have lower CD4 counts and were more likely to have AIDS. Despite this, there was decreased mortality in later years of HAART initiation at GHESKIO-Haiti, suggesting an improvement in care over time. Structural factors, such as interruptions in drug supply [16] and shortage of staff [17] in Peru and bureaucracy and delays in Chile [15], may have affected program effectiveness.

The higher mortality rates in GHESKIO-Haiti and IHSS/HE-Honduras, independent of baseline CD4 count, may be a reflection of higher mortality rates in the general population. Nation-wide estimates for life expectancy at birth are lower for Haiti (61.3 years) and Honduras (70.4 years) than the other five countries with participating sites (75.5, 72.6, 78.7, 76.4, and 71.7 years for Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Peru, respectively), although such data may not accurately represent background mortality in the specific locations of our clinic[18]. Higher mortality rates may be indicative of chronic poverty and malnutrition. In both men and women, weight and hemoglobin at therapy initiation were consistently lower for patients in GHESKIO-Haiti than in other sites. Several previous studies, including ones conducted in Haiti, have demonstrated the deleterious effect of malnutrition on AIDS progression in resource-poor settings [14, 19–22]. Consistent with other studies [23, 24], we observed strong associations between weight and mortality in GHESKIO-Haiti and IMTAvH-Peru, and between hemoglobin and mortality in GHESKIO-Haiti, IHSS/HE-Honduras, and INNSZ-Mexico.

Unfortunately, data on causes of death were not available for most sites and therefore were not examined.

The high mortality rate reported here in the first few months following HAART initiation is in agreement with other reports from resource-limited countries [5, 25–27] and highlights the need to determine causes of early death so that specific public health strategies may be developed.

With the exception of FH-Argentina, rates of loss to follow-up were fairly low (≤5%) across sites. The high rate of lost-to-follow-up in FH-Argentina raises concerns regarding its low mortality estimate. However, because those lost tended to have characteristics at HAART initiation similar to those alive after one year, and because the mortality estimate adjusted for baseline covariates was nearly identical to the unadjusted estimate, it seems likely that the mortality rate in FH-Argentina is not significantly higher than estimated in Figure 1. The high rate of loss to follow-up in FH-Argentina may reflect patients seeking care at clinics not included in this cohort, as there are many treatment/clinic options in Buenos Aires. In contrast, patients lost to follow-up at other sites tended to have baseline characteristics intermediate between those alive and those dead after one year (FA-Chile, INNSZ-Mexico, and IMTAvH-Peru) or similar to those dead (GHESKIO-Haiti). Although the latter observation is consistent with recent data reported from lower-income countries in Africa, Asia, and South America [28], the present study suggests that losses to follow-up may have different meanings in different settings. Similar to the findings of Brinkhof et al., we observed higher rates of loss to follow-up for patients initiating HAART in more recent years. This may reflect rapid scale-up paired with inability to retain patients [28]. It should be recognized that our definition of loss to follow-up was chosen to ensure comparability with other studies that have estimated one-year mortality in developing countries [5]. Other definitions of loss to follow-up (e.g., 3 months without a visit) are likely to be more meaningful when evaluating other clinical outcomes or clinic programmatic performance.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the impact of adherence to therapy, a well-known prognostic factor demonstrated in several studies [29–31], was not addressed. In contrast to developed countries, factors influencing adherence to antiretroviral therapy have been less studied in resource-limited settings [32, 33]. Second, on-site data audits revealed data errors for all CCASAnet sites, although none serious enough to warrant site exclusion. Specific results of the audits, which appear to be unique among multi-cohort observational HIV studies, are beyond the scope of this study and will be presented elsewhere. Tendency towards over-diagnosis of AIDS was observed in HUCFF-Brazil, indicating a possible classification bias. This may reflect local practices and partially explains the imprecise hazard estimates for this variable in the multivariable model. Although we only used routinely collected variables and employed statistical techniques to account for differences between those with and without missing measurements, hazard ratios could still be biased due to missing data. Finally, additional heterogeneity between cohorts may be present due to differences in population genetics or infecting HIV subtypes, factors which were not considered in the present analysis.

The results reported here have important public health implications. The finding of a large number of patients starting HAART at advanced stages of disease with consequent impact on mortality rates has implications for public health planning and HIV prevention. The overall rate of late diagnosis in our cohort (76%), defined as CD4 count <200 cells/μL or AIDS at baseline, is nearly twice as high as that observed in developed countries. For example, using the same definition, studies from France and Italy reported rates of late diagnosis of 36% and 39%, respectively [34, 35]. In addition, the rate of patients starting HAART at advanced stages of disease did not appear to be improving with time at most CCASAnet sites. Late presenting patients are more likely to require hospitalization and experience multiple opportunistic conditions simultaneously [36], and to utilize more health care resources [37]. From a prevention perspective, it is likely that late diagnosis increases risk of HIV transmission, as studies suggest that transmission is associated with lack of knowledge about HIV status [38], and high plasma viral load [39].

In conclusion, in the first multi-cohort study to describe prognosis after HAART initiation in Latin America and the Caribbean, we found that despite considerable variability between sites, the overall mortality rate at one year is similar to that reported in other resource-limited settings. Differences across sites may reflect, at least in part, diverse background mortality rates, local practices and/or national programmatic characteristics. Further operations research is necessary to elucidate this important issue.

Writing Commitee: Suely H. Tuboi1, Mauro Schechter1, Catherine C. McGowan2, Carina Cesar3, Alejandro Krolewiecki3, Pedro Cahn3, Marcelo Wolff4, Jean W. Pape5, Denis Padgett6, Juan Sierra Madero7, Eduardo Gotuzzo8, Daniel R. Masys2, Bryan E. Shepherd2

1Projeto Praça Onze, Hospital Universitario Clementino Fraga Filho and Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

2Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA

3Fundación Huesped and Hospital Fernandez, Buenos Aires, Argentina

4Fundación Arriaran and Facultad de Medicina, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile

5Les Centres GHESKIO, Port-au-Prince, Haiti

6Instituto Hondureño de Seguridad Social and Universidad Autónoma de Honduras, Tegucigalpa, Honduras

7Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Medicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubiran, México City, México

8Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia Facultad de Medicina and Instituto de Medicina Tropical Alexander von Humboldt, Lima, Perú

CCASAnet Steering Group: Pedro Cahn (Argentina), Mauro Schechter (Brazil), Marcelo Wolff (Chile), Jean William Pape (Haiti), Denis Padgett (Honduras), Juan Sierra Madero (Mexico), Eduardo Gotuzzo (Peru), Daniel Masys (USA).

References

- 1.UNAIDS. AIDS epidemic update, December 2007. WHO; 2007. Available at http://www.unaids.org/en/HIV_data/2007EpiUpdate/default.asp. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. Geneve: 2007. Towards Universal Access Progress Report. Available at http://www.who.int/hiv/mediacentre/universal_access_progress_report_en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egger M, May M, Chene G, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou J, Kumarasamy N, Ditangco R, et al. The TREAT Asia HIV Observational Database: baseline and retrospective data. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;38:174–179. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000145351.96815.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, et al. Mortality of HIV-1-infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet. 2006;367:817–824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68337-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGowan CC, Cahn P, Gotuzzo E, et al. Cohort Profile: Caribbean, Central and South America Network for HIV research (CCASAnet) collaboration within the International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS (IeDEA) programme. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:969–976. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shafer JL. Analysis of Incomplete Multivariate Data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrell FEJ. Regression Modeling Strategies With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic Regression, and Survival Analysis. New York: Springer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith-Warner SA, Spiegelman D, Ritz J, et al. Methods for pooling results of epidemiologic studies: the Pooling Project of Prospective Studies of Diet and Cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1053–1064. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robins JM, Finkelstein DM. Correcting for noncompliance and dependent censoring in an AIDS Clinical Trial with inverse probability of censoring weighted (IPCW) log-rank tests. Biometrics. 2000;56:779–788. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Louis C, Ivers LC, Smith Fawzi MC, et al. Late presentation for HIV care in central Haiti: factors limiting access to care. AIDS Care. 2007;19:487–491. doi: 10.1080/09540120701203246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Infante C, Zarco A, Cuadra SM, et al. [HIV/AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: the case of health care providers in Mexico] Salud Publica Mex. 2006;48:141–150. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342006000200007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Severe P, Leger P, Charles M, et al. Antiretroviral therapy in a thousand patients with AIDS in Haiti. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2325–2334. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolff MJ, Beltran CJ, Vasquez P, et al. The Chilean AIDS cohort: a model for evaluating the impact of an expanded access program to antiretroviral therapy in a middle-income country--organization and preliminary results. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:551–557. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000185573.98472.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Echevarria J, Lopez de Castilla D, Seas C, et al. Scaling-up highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in Peru: problems on the horizon. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:625–626. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000242460.35768.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sebastian JL, Munoz M, Palacios E, et al. Scaling up HIV treatment in Peru: applying lessons from DOTS-Plus. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic Ill) 2006;5:137–142. doi: 10.1177/1545109706291394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.PAHO. Edited by Health Surveillance DPaC. World Health Organization; 2008. Health situation in the americas. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fawzi WW, Msamanga GI, Spiegelman D, et al. A randomized trial of multivitamin supplements and HIV disease progression and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:23–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fawzi W, Msamanga G, Spiegelman D, et al. Studies of vitamins and minerals and HIV transmission and disease progression. J Nutr. 2005;135:938–944. doi: 10.1093/jn/135.4.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta S, Fawzi W. Effects of Vitamins, Including Vitamin A, on HIV/AIDS Patients. Vitam Horm. 2007;75:355–383. doi: 10.1016/S0083-6729(06)75013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paton NI, Sangeetha S, Earnest A, et al. The impact of malnutrition on survival and the CD4 count response in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2006;7:323–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stringer JS, Zulu I, Levy J, et al. Rapid scale-up of antiretroviral therapy at primary care sites in Zambia: feasibility and early outcomes. Jama. 2006;296:782–793. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.7.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moh R, Danel C, Messou E, et al. Incidence and determinants of mortality and morbidity following early antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV-infected adults in West Africa. Aids. 2007;21:2483–2491. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f09876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johannessen A, Naman E, Ngowi BJ, et al. Predictors of mortality in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy in a rural hospital in Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis. 2008;8:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-8-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lawn SD, Myer L, Harling G, et al. Determinants of mortality and nondeath losses from an antiretroviral treatment service in South Africa: implications for program evaluation. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:770–776. doi: 10.1086/507095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zachariah R, Fitzgerald M, Massaquoi M, et al. Risk factors for high early mortality in patients on antiretroviral treatment in a rural district of Malawi. Aids. 2006;20:2355–2360. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32801086b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Myer L, et al. Early loss of HIV-infected patients on potent antiretroviral therapy programmes in lower-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:559–567. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.044248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wood E, Montaner JS, Chan K, et al. Socioeconomic status, access to triple therapy, and survival from HIV-disease since 1996. Aids. 2002;16:2065–2072. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200210180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, et al. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4+ cell count is 0.200 to 0.350 × 10(9) cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:810–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hogg RS, Heath K, Bangsberg D, et al. Intermittent use of triple-combination therapy is predictive of mortality at baseline and after 1 year of follow-up. Aids. 2002;16:1051–1058. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200205030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofer CB, Schechter M, Harrison LH. Effectiveness of Antiretroviral Therapy Among Patients Who Attend Public HIV Clinics in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:967–971. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delpierre C, Dray-Spira R, Cuzin L, et al. Correlates of late HIV diagnosis: implications for testing policy. Int J STD AIDS. 2007;18:312–317. doi: 10.1258/095646207780749709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Girardi E, Aloisi MS, Arici C, et al. Delayed presentation and late testing for HIV: demographic and behavioral risk factors in a multicenter study in Italy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;36:951–959. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200408010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sabin CA, Smith CJ, Gumley H, et al. Late presenters in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: uptake of and responses to antiretroviral therapy. Aids. 2004;18:2145–2151. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200411050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krentz HB, Auld MC, Gill MJ. The high cost of medical care for patients who present late (CD4 <200 cells/microL) with HIV infection. HIV Med. 2004;5:93–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2004.00193.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. Aids. 2006;20:1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castilla J, Del Romero J, Hernando V, et al. Effectiveness of highly active antiretroviral therapy in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40:96–101. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000157389.78374.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]