Abstract

Purpose

To assess the long-term stability of improvements in symptoms and signs in 9- to 17-year-old children enrolled in the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial who were asymptomatic after treatment for convergence insufficiency (CI).

Methods

Seventy-nine patients who were asymptomatic after a 12-week therapy program for CI were followed for 1 year [33/60 in office-based vergence/accommodative therapy (OBVAT), 18/54 in home-based pencil push-ups (HBPP), 12/57 in home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy and pencil push-ups (HBCVAT+), and 16/54 in office-based placebo therapy (OBPT)]. Symptoms and clinical signs were measured 6 months and 1 year after completion of the 12-week therapy program. The primary outcome measure was the mean change on the CI Symptom Survey (CISS). Secondary outcome measures were near point of convergence (NPC), positive fusional vergence at near (PFV), and proportions of patients who remained asymptomatic or who were classified as successful or improved based on a composite measure of CISS, NPC, and PFV.

Results

One-year follow-up visit completion rate was 89% with no significant differences between groups (p=0.26). There were no significant changes in the CISS in any treatment group during the 1-year follow-up. The percentage who remained asymptomatic in each group was 84.4% (27/32) for OBVAT, 66.7% (10/15) for HBPP, 80% (8/10) for HBCVAT+, and 76.9% (10/13) for OBPT. The percentage who remained either successful or improved 1-year post-treatment was 87.5% (28/32) for OBVAT, 66.6% (10/15) for HBPP, 80% (8/10) for HBCVAT+, and 69.3% (9/13) for OBPT.

Conclusions

Most children aged 9 to 17 years who were asymptomatic after a 12-week treatment program of OBVAT for CI maintained their improvements in symptoms and signs for at least 1 year after discontinuing treatment. Although the sample sizes for the home based and placebo groups were small, our data suggest that a similar outcome can be expected for children who were asymptomatic after treatment with HBPP and HBCVAT+.

Keywords: convergence insufficiency, asthenopia, vision therapy, orthoptics, vergence/accommodative therapy, pencil push-ups, computer vergence/accommodative therapy, placebo therapy, exophoria, eyestrain, symptom survey

Recently completed randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that 12 weeks of office-based vergence/accommodative therapy with home reinforcement (OBVAT) is more effective than home-based pencil push-ups therapy (HBPP), home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy and pencil push-ups (HBCVAT+), or office-based placebo therapy (OBPT) in improving both the symptoms and clinical signs associated with symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children 9 to 17 years old.1,2 These data are important because they represent the first results from randomized clinical trials comparing the effectiveness of the three most commonly prescribed forms of vision therapy/orthoptics for convergence insufficiency. However, these previously reported findings only provided information about results immediately after treatment completion. They did not indicate whether the treatment effect is sustained over time.

The literature on the long-term effectiveness of vision therapy/orthoptics for convergence insufficiency consists of a small number of studies with significant design limitations including retrospective design, small sample size, variable lengths of follow-up, unmasked examiners, and adult patient populations.3–6 In addition, previous research has only addressed home-based vision therapy/orthoptics. Thus, there are no well-controlled prospective studies on the long-term effectiveness of vision therapy/orthoptics for successfully treated children with symptomatic convergence insufficiency.

We conducted a randomized trial of 221 children ages 9 to 17 years old with symptomatic convergence insufficiency.2 Patients were randomized to 12 weeks of OBVAT, HBPP, HBCVAT+, or OBPT. All patients were followed for 12 months after completion of the 12-week treatment program regardless of the outcome. Patients who demonstrated sufficient improvement on the CI Symptom Survey (CISS)7,8 were considered “asymptomatic” (i.e., CISS score <16) at the 12-week outcome. Herein, we report long-term follow-up results for these patients who were asymptomatic post treatment with an emphasis on within group analysis.

METHODS

The tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki were followed throughout the study. The institutional review boards of all participating centers approved the protocol and informed consent documents. The parent or guardian (subsequently referred to as “parent”) of each study patient gave written informed consent and each patient assented to participate. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) authorization was obtained from the parent. Study oversight was provided by an independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (see Acknowledgments). This study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as the Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial (CITT). The design and results of the randomized trial have been published in separate manuscripts2,9 and are only partially described herein.

Eligibility

Major eligibility criteria for the original trial included children ages 9 to 17 years, a Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Score (CISS ) score of ≥16, an exodeviation at near at least 4 prism diopters (Δ) greater than at far, a receded NPC break (6 cm or greater), and insufficient positive fusional vergence at near (PFV) (convergence amplitudes). Insufficient PFV was considered either Sheard’s criterion (PFV less than twice the near phoria)10 or minimum PFV of ≤15Δ base-out blur or break).

Eligible patients who consented to participate were stratified by site and randomly assigned with equal probability using a permuted block design to HBPP, HBCVAT+, OBVAT, or OBPT.

Long-Term Follow-up

At completion of the 12 week treatment program, patients were classified as either asymptomatic (CISS score < 16) or symptomatic (CISS score ≥ 16). Symptomatic patients were offered alternative treatment at no cost. Asymptomatic patients were assigned home maintenance therapy (described below) for 15 minutes per week for the initial 6 months following treatment discontinuation. No home therapy was prescribed between the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits. An examiner masked to the patients’ original treatment group performed a sensorimotor examination and administered the CISS at the follow-up visits scheduled 6 and 12 months after treatment completion.9

Maintenance Therapy

Patients in each group were instructed to perform 15 minutes of maintenance therapy once per week for the first 6 months following completion of treatment. The OBVAT group performed one convergence technique (Brock String or Barrel Card) and one fusional vergence technique (Eccentric Circles or Lifesaver Cards). Patients in the HBPP were asked to do pencil push-ups for 15 minutes while those in the HBCVAT+ group did 5 minutes of pencil push-ups and 10 minutes of computer vergence therapy. The patients in the OBPT group were instructed to use the TV Trainer (watch television covered by a neutral density filter while wearing Polaroid glasses) for 10 minutes and work with playing cards (plays cards while wearing Polaroid glasses) for 5 minutes.

Masking & Therapy Adherence

At completion of the 6- and 12-month examinations, the examiners continued to be masked to the patients original treatment group and were asked to indicate if they thought they were able to identify the patient’s treatment group before the testing was completed; however, the examiner was not asked to try to identify the treatment group.

At the 6-month follow-up visit, therapists were asked to estimate the percentage of time they thought that their patients adhered to the prescribed maintenance therapy using possible responses options of “0%”, “1–24%”, “25–49%”, “50–74%”, “75–99%” and “100%.” The therapists’ estimate was based on a discussion with the patient about home therapy.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the mean change in the CISS score from the 12-week outcome visit to the 6- and 12-month follow-up examinations. The CISS, described in detail in other publications,7,8 is a questionnaire consisting of 15 items. The examiner reads the questions while the child views a card with 5 possible response options (never, infrequently, sometimes, fairly often, always). Each response is scored as 0 to 4 points, with 4 representing the highest frequency of symptom occurrence (i.e., always). The 15 items are summed to obtain the total CISS score. The lowest possible score (least symptoms) is 0 and the highest is 60 (most symptomatic). The CISS was administered before any clinical testing and repeated after the sensorimotor examination was completed; the average of the 2 CISS scores was used for analysis. Based on our previous work,7,8 a CISS score of less than 16 is considered “asymptomatic” and a decrease of at least 10 or more points is considered an “improved” symptom level.

Secondary outcome measures were the mean change in NPC and PFV from treatment discontinuation to the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits. Near point of convergence was measured by bringing a target (a single column of 20/30 equivalent letters at 40 cm) slowly towards the child until the child reported that the letters became double or the examiner observed loss of fusion. Positive fusional vergence was measured with a horizontal prism bar while the patient fixated a target with a single column of 20/30 equivalent letters at 40 cm. NPC and PFV were administered three times with the average of the 3 measures used for analysis. A “normal” NPC was defined as less than 6 cm and an “improved” NPC was defined as an improvement (decrease) in NPC of more than 4 cm. To be classified as having “normal” PFV a patient had to pass Sheard’s criteria and have a PFV blur/break of more than 15Δ. Improvement in PFV was defined as an increase of 10Δ or more.

A composite measure of both symptoms and signs (CISS, NPC and PFV) was used to classify a patient’s treatment outcome as successful, improved, or nonresponsive to treatment (i.e., a nonresponder). A “successful” outcome was defined as a CISS score of <16 and achievement of both a normal NPC (i.e., less than 6 cm) and normal PFV (i.e., greater than 15Δ and passing Sheard’s criterion). Treatment outcome was considered to be “improved” when the CISS score was <16 or there was a 10-point decrease from baseline in the CISS score, and at least one of the following was present: a normal NPC, improvement from baseline in NPC of more than 4 cm, normal PFV, or a 10Δ or greater increase from baseline in PFV. Patients who did not meet the criteria for a “successful” or “improved” outcome were considered “non-responders.” The proportion of patients who were classified as successful or improved was determined at 6 and 12 months after completion of treatment.

Statistical Methods

The 6- and 12-month follow-up data in this report includes all asymptomatic patients (at the 12-week outcome examination) who were examined 6 months and 12 months post-treatment. Asymptomatic patients who received alternative treatment (i.e., treatment other than that to which they were assigned) were classified as symptomatic for analysis of symptom level at 6- and 12-months and as non-responders for analysis of the composite measure.

We limited our statistical analysis to within-group changes rather than between-group changes because of the small sample size and low power to detect differences. Comparisons between the asymptomatic patients who attended and those who missed their 12-month follow-up visit were performed using Wilcoxon rank sum and chi-square tests. Analysis of covariance models were used to estimate the adjusted mean change in each outcome measure from treatment discontinuation (week 12 examination) to the 6- and 12-month follow-up visits. The only covariate included in the model was the value of the outcome measure (CISS, NPC or PFV) at the 12-week outcome examination. The estimated variance from the ANCOVA model was used to calculate 95% confidence intervals (CI) for the adjusted mean change in the CISS score, NPC, and PFV. Change was calculated so that values greater than zero indicate improvement while values less than zero indicate a decline. All analyses were performed using SAS (Cary, NC; version 9.1.3).

RESULTS

Patient Follow-up

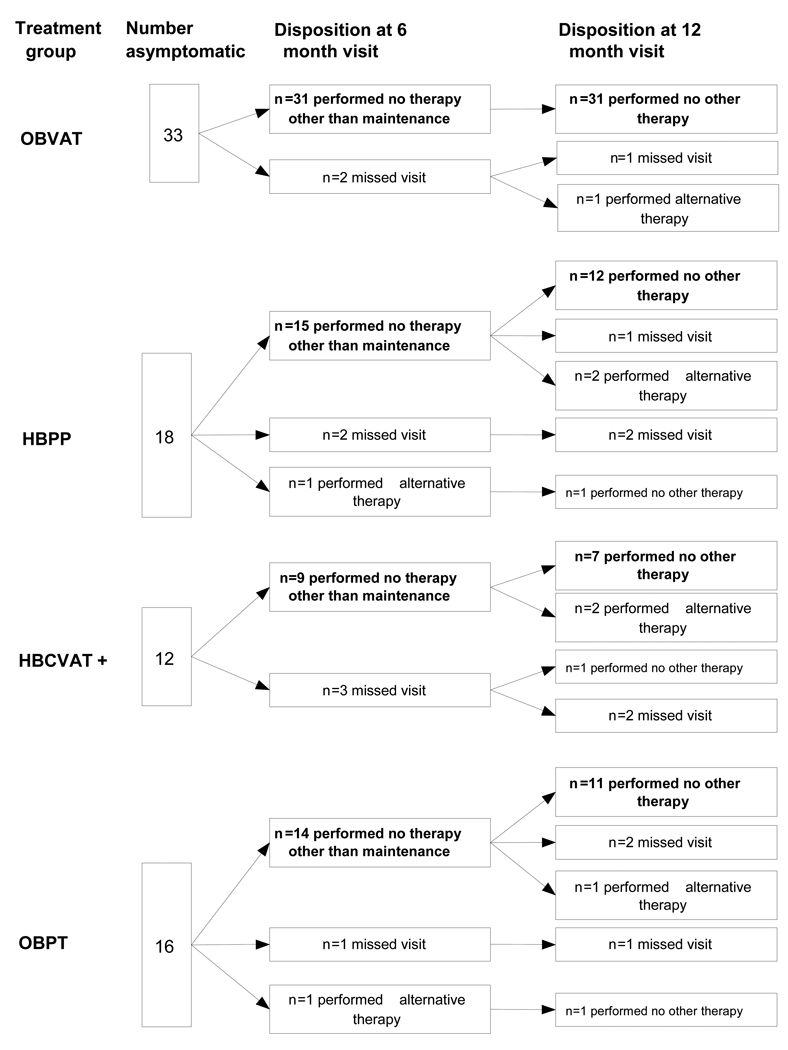

As shown in Figure 1, 90% (71/79) of the patients who were asymptomatic after treatment completed the 6-month visit. Two of these patients (1 HBPP and 1 OBPT) reported receiving alternative therapy prior to the 6-month follow-up visit. Seventy of the original 79 (89%) who were asymptomatic after treatment returned for the 12-month follow-up visit. An additional 6 patients (1 assigned to OBVAT, 2 to HBPP, 2 to HBCVAT+, and 1 to OBPT) reported that they received alternative treatment between the 6- and 12-month visits. There were no significant differences in the completion rate between treatment groups at either the 6- or 12-month follow-up visit (p = 0.28 and 0.26, respectively). Although fewer children (1 of 32 or 3%) in the OBVAT group reported seeking alternative treatment in contrast to 20% (3 of 15), 20% (2 of 10), and 15% (2 of 13) for the HBPP, HBCVAT+ and OBPT groups, respectively, these differences are statistically non-significant (p=0.12).

Figure 1.

Patient follow-up by Treatment Group.

Comparisons were made between the patients who returned (n=70) and those who did not return (n=9) for their 12-month examinations (Table 1) Patients of Hispanic ethnicity (100% versus 30%, p < 0.001) and males (68.6% versus 33.3%, p = 0.038) were less likely to return for their 12-month visit. There were no other differences between the two groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of characteristics between post-treatment asymptomatic CITT patients who completed the 12-month follow-up visit and those who did not.

| Characteristic | Completed visit (n=70) |

Missed visit (n=9) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (std) age (years) | 12.0 (2.4) | 13.0 (2.7) | 0.26 |

| % female | 68.6 | 33.3 | 0.038 |

| % White | 54.3 | 55.6 | 0.94 |

| % Hispanic | 30.0 | 100.0 | <0.001 |

| % with parent-reported ADHD | 5.7 | 22.2 | 0.18 |

| Mean (std) CISS score | |||

| At eligibility | 25.6 (8.1) | 25.6 (9.7) | 0.22 |

| At week 12 | 8.6 (4.8) | 7.1 (4.5) | 0.33 |

| Mean (std) NPC break (cm) | |||

| At eligibility | 13.3 (6.3) | 11.7 (6.6) | 0.27 |

| At week 12 | 5.1 (3.4) | 6.8 (6.3) | 0.94 |

| Mean (std) PFV (Δ) | |||

| At eligibility | 11.2 (3.8) | 11.2 (1.6) | 0.92 |

| At week 12 | 25.9 (11.1) | 24.9 (11.3) | 0.82 |

| Mean (std) accommodative amplitude (D) | |||

| At eligibility | 9.8 (3.6) | 10.4 (3.1) | 0.49 |

| At week 12 | 15.1 (5.2) | 12.8 (4.3) | 0.22 |

| Mean (std) accommodative facility (cpm) | |||

| At eligibility | 7.2 (4.3) | 6.3 (4.6) | 0.41 |

| At week 12 | 14.2 (5.6) | 11.2 (5.6) | 0.17 |

| Mean (std) phoria at near (Δ) | |||

| At eligibility | 9.4 exo (4.5) | 7.3 exo (2.8) | 0.20 |

| At week 12 | 7.8 exo (5.3) | 6.9 exo (3.5) | 0.76 |

ADHD: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

CISS: Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey

NPC: Near Point of Convergence

PFV: Positive Fusional vergence at near

Masking and Adherence with Maintenance Therapy

None of the examiners felt that they were able to identify group assignments at the 6-month visit; one examiner indicated that he thought he knew the patient’s treatment group at the 12-month visit. At the 6-month visit, patient adherence of at least 75% to the prescribed home maintenance therapy was judged by the therapist for 45%, 64%, 60%, and 44% of the patients assigned to OBVAT, HBPP, HBCVAT+, and OBPT, respectively. These estimates were not significantly different from each other (p = 0.83).

Office-based Vergence/Accommodative Therapy with Home Reinforcement

As shown in Figure 1, 31/33 of the OBVAT group completed the 6-month visit and none of these patients had received alternative therapy prior to that visit. The mean change in the CISS was 0.2 (95% CI of −1.6, +2.1) (Table 2). Twenty-eight of the 31 (90%) patients remained asymptomatic. The mean change in NPC break was significantly different than zero (mean = 1.0cm; 95% CI +0.2 cm, +1.9 cm). There was no change in PFV (mean = 2.3 Δ; 95% CI −1.0Δ, +5.5Δ) (Table 2). Using the composite outcome classification, 90% of the 31 patients were classified as either successful (21) or improved (7) at the 6-month follow-up visit (Table 3).

Table 2.

Mean adjusted change* and 95% confidence interval in each outcome measure at 6- and 12-months, by treatment group for asymptomatic CITT patients post-treatment who did not receive alternative treatment prior to the follow-up visit.

| Outcome/Visit | OBVAT | HBPP | HBCVAT+ | OBPT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Convergence Insufficiency Symptom Survey | ||||

| 6 Month | 0.2 (−1.6, +2.1) |

−5.8 (−12.4, +0.8) |

0.2 (−3.4, +3.8) |

−2.0 (−5.0, +1.1) |

| 12 Month | −0.6 (−3.1, +1.8) |

−1.9 (−5.9, +2.0) |

0.1 (−4.8, +4.9) |

2.0 (−2.1, +6.1) |

| Near Point Convergence break (cm) | ||||

| 6 Month | 1.0 (+0.2, +1.9) |

−0.1 (−1.2, +1.1) |

−0.9 (−2.4, +0.5) |

0.4 (−0.9, +1.6) |

| 12 Month | 0.2 (−0.9, +1.3) |

0.1 (−1.6, +1.8) |

0.5 (−1.6, +2.6) |

0.3 (−1.7, +2.3) |

| Positive Fusional Vergence (Δ) | ||||

| 6 Month | 2.3 (−1.0, +5.5) |

−3.5 (−8.0, +1.0) |

−2.2 (−8.0, +3.5) |

0.1 (−4.6, +4.9) |

| 12 Month | 3.0 (+0.04, +5.9) |

−0.3 (−4.9, +4.3) |

0.6 (−4.9, +6.2) |

−1.3 (−6.1, +3.5) |

Change adjusted for measurement obtained at the week 12 visit and calculated such that values greater than zero indicate improvement while values less than zero indicate a decline/deterioration.

OBVAT: Office-based vergence/accommodative therapy with home reinforcement

HBPP: Home-based pencil push-up therapy

HBCVAT+: Home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy and pencil push-ups

OBPT: Office-based placebo therapy with home reinforcement

Table 3.

Number (%) of patients in each category of the composite measure of outcome, at 6- and 12-month follow-up visit.

| Category | OBVAT | HBPP | HBCVAT+ | OBPT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 12 Masked Examination | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 33 | 18 | 12 | 16 |

| 6-month follow-up visit | ||||

| Completed visit | 31 | 16 | 9 | 15 |

| Received additional treatment? | ||||

| No | 31 (100) | 15 (93.8) | 9 (100) | 14 (93.3) |

| Yes | 0 | 1 (6.2) | 0 | 1 (6.7) |

| Symptom level | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 28 (90.3) | 10 (62.5) | 8 (88.9) | 12 (80.0) |

| Symptomatic | 3 (9.7) | 6 (37.5) | 1 (11.1) | 3 (20.0) |

| Composite Outcome | ||||

| Successful | 21 (67.7) | 4 (25.0) | 5 (55.6) | 6 (40.0) |

| Improved | 7 (22.6) | 7 (43.8) | 3 (33.3) | 5 (33.3) |

| Non-responder | 3 (9.7) | 5 (31.2) | 1 (11.1) | 4 (26.7) |

| 12-month follow-up visit | ||||

| Completed visit | 32 | 15 | 10 | 13 |

| Received additional treatment? | ||||

| No | 31 (96.9) | 12 (80.0) | 8 (80.0) | 11 (84.6) |

| Yes | 1 (3.1) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (20.0) | 2 (15.4) |

| Symptom level | ||||

| Asymptomatic | 27 (84.4) | 10 (66.7) | 8 (80.0) | 10 (76.9) |

| Symptomatic | 5 (15.6) | 5 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | 3 (23.1) |

| Composite outcome | ||||

| Successful | 18 (56.3) | 5 (33.3) | 3 (30.0) | 5 (38.5) |

| Improved | 10 (31.2) | 5 (33.3) | 5 (50.0) | 4 (30.8) |

| Non-responder | 4 (12.5) | 5 (33.3) | 2 (20.0) | 4 (30.8) |

OBVAT: Office-based vergence/accommodative therapy with home reinforcement

HBPP: Home-based pencil push-up therapy

HBCVAT+: Home-based computer vergence/accommodative therapy and pencil push-ups

OBPT: Office-based placebo therapy with home reinforcement

All 31 patients who had attended their 6-month visit returned for their 12-month follow-up visit and reported no additional therapy during the latter 6 months (Figure 1). One subject who missed the 6-month visit but returned for the 12-month visit reported receiving other therapy since treatment discontinuation at the end of the trial.

The mean change in the CISS at the 12-month follow-up visit was not significantly different from zero (mean = −0.6, 95% CI of −3.1, +1.8) and 27 (84%) patients were still considered asymptomatic. There was no significant change in NPC (mean = 0.2cm, 95% CI −0.9, +1.3). A statistically significant improvement was noted in PFV (mean = 3.0Δ, 95% CI +0.04, +5.9) (Table 2) with the majority of this improvement occurring in the first 6 months of follow-up (mean = 2.3Δ at the 6-month visit). Using the composite outcome classification, 87% (28/31) the patients remained either successful (56%) or improved (31%) at the 12-month follow-up visit (Table 3).

Home-based and Office-based Placebo Therapy Groups

Because HBPP, HBVACT+, and OBPT were less effective than OBVAT, there were fewer asymptomatic patients (Figure 1) eligible for long-term follow-up. Among the 31 patients (12 HBPP, 8 HBCVAT+, and 11 OBPT) who returned for follow-up at 12 months and had not received alternative treatment, there were no significant changes in the mean CISS score, NPC, or PFV in either of the home-based treatments or the placebo therapy group (Table 2).

In the HBPP group, the mean change in the CISS score at the 12-month follow-up visit was −1.9 (95% CI −5.9, +2.0) and 10 (66.7%) patients were still considered asymptomatic. There was no significant change in NPC (mean = 0.1cm, 95% CI −1.6, +1.8) or PFV (mean = −0.3Δ, 95% CI – 4.9, +4.3) (Table 2). Using the composite outcome classification, 67% (10/15) of the patients remained either successful (5/15, 33.3%) or improved (5/15, 33.3%) (Table 3).

The mean change in the CISS score at the 12-month follow-up visit for the HBCVAT+ group was 0.1 (95% CI −4.8, +4.9) and 8 (80%) patients were still considered asymptomatic. There was no significant change in NPC (mean = 0.5cm, 95% CI −1.6, +2.6) or PFV (mean = 0.6Δ, 95% CI −4.9, +6.2) (Table 2). Using the composite outcome classification, 80% (8/10) the patients remained either successful (3/10, 30%) or improved (5/10, 50%) (Table 3).

In the OBPT group, the mean change in the CISS score at the 12-month follow-up visit was 2.0 (95% CI −2.1, +6.1) and 10 (77%) patients were still considered asymptomatic. There was no significant change in NPC (mean = 0.3cm, 95% CI −1.7, +2.3) or PFV (mean = −1.3Δ, 95% CI −6.1, +3.5) (Table 2). Using the composite outcome classification, 69% (9/13) of the patients remained either successful (5/13, 39%) or improved (4/13, 31%) (Table 3).

Comparison between Baseline and Week 12 Characteristics for Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Children at the 12-month Examination

Although there were no baseline characteristics that were associated with an increase in symptoms at 12 months, the mean CISS score after discontinuation of the original treatment was significantly different between those who remained asymptomatic and those who were symptomatic at 12 months (<0.001). The mean CISS score upon completion of the 12 week treatment program was 7.6 (± 4.5) in the 55 children who remained asymptomatic at 12 months compared to 12.2 (± 4.0) in the group of 15 children who became symptomatic (5 in OBVAT, 5 in HBPP, 2 in HBCVAT+, and 3 in OBPT).

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of 79 children aged 9 to 17 years who were asymptomatic after completing 12 weeks of therapy for symptomatic convergence insufficiency, the improvements that occurred in symptoms and clinical signs in all 4 treatment groups were generally sustained for one year after the treatment program was discontinued. The overall 1-year probability of symptoms or signs recurring varied from a high of 33% in the HBPP group to a low of 16% in the OBVAT group. The modest recurrence rate in the OBVAT group cannot be compared with that reported in previous studies3–6 because those studies only included adult patients and investigated home-based vision therapy/orthoptics. Moreover, these studies had other design issues such as small sample sizes, high dropout rates, variable lengths of follow up, varying criteria for successful treatment, or retrospective investigations. There are also no previous studies with long-term follow-up for either HBPP or HBCVAT+ in children that could be used for comparisons.

The patient cohort in the current study included formerly symptomatic children with convergence insufficiency who were asymptomatic upon completion of a 12-week treatment program and performed maintenance therapy for 6 months following completion of treatment. Because OBVAT was found to be significantly more effective than the HBPP, HBVACT+, and OBPT, there were considerably more patients who were assigned to OBVAT who were asymptomatic post-treatment and hence eligible for the long-term follow-up aspect of the CITT. In this group, the mean symptom score was remarkably stable as were the mean clinical measures of NPC and PFC with no significant changes occurring for the worse or for the better. The number of children who remained asymptomatic 1 year later was high (84%). When taking both the NPC and PFV into consideration with the CISS score, 87% of the children who were asymptomatic after 12 weeks of OBVAT remained either successful or improved 1-year post-treatment. These data show there is long-term benefit to OBVAT for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children.

Sixty-seven to 80% of children who were asymptomatic after a 12-week treatment program of home-based therapy or office-based placebo therapy maintained their improvements in symptoms and signs for at least 1 year after discontinuing treatment. However, the sample size for the two home-based therapy and the office-based placebo therapy groups was small and thus, caution is necessary when interpreting the long-term data for these groups. Because of the small sample sizes in the home-based therapy and placebo groups we have emphasized within-group analysis, rather than between-group comparisons.

The patients who remained successful or improved in the placebo therapy group represent patients who improved due to the placebo effect, natural history of the disease, or regression to the mean. Because similar numbers of successful or improved patients were found in the home-based therapy groups (HBPP and HBCVAT+) and the placebo group, this suggests that additional studies are necessary to determine if home-based therapy is any more effective than placebo treatment.

There were differences among the 4 groups in the percentage of patients who received alternative treatments. Although these differences are statistically non-significant due to small sample size, a trend in the percentages is apparent. Only 3% of subjects in the OBVAT group reported seeking alternative therapy in contrast to 20%, 20%, and 15% for the HBPP, HBCVAT+, and OBPT groups, respectively. In future research we plan to ask parents why they chose to seek alternative therapy.

Our study design included the prescription of maintenance therapy for the first 6 months and we do not know whether the long-term success would have been similar if the patients had not been prescribed maintenance therapy. It is also not clear what role the different types of maintenance therapy had on the study results and what proportion of patients adhered with the prescribed treatments.

We could identify no source of bias or confounding factors to explain our findings. The overall follow-up rate was high and there were no significant differences in the follow up between groups at the 12-month visits. While Hispanic subjects and males were less likely to return for their 12-month follow-up visit, neither ethnicity nor gender has been shown to be related to symptoms, NPC, or PFV. The investigators performing examinations were masked to the patients’ treatment group and the patients in the two office-based treatment groups were effectively masked as well.2

CONCLUSIONS

Most children aged 9 to 17 years who were asymptomatic after a 12-week treatment program of OBVAT for convergence insufficiency maintained their improvements in symptoms and signs for at least 1 year after discontinuing treatment. Although the sample sizes for the home based and placebo groups were small, our data suggest that a similar effect can be expected for children who were asymptomatic after treatment with HBPP and HBCVAT+.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Supported through a cooperative agreement from the National Eye Institute.

THE CONVERGENCE INSUFFICIENCY TREATMENT TRIAL INVESTIGATOR GROUP

Writing Committee

Lead Authors: Mitchell Scheiman, OD; Marjean Kulp, OD, MS, Susan Cotter, OD,MS, Gladys Lynn Mitchell, MAS, Michael Rouse, OD, MS, Richard Hertle, MD

Additional Writing Committee Members: (Alphabetical): Jeffrey Cooper, MS, OD, Rachel Coulter, OD, Michael Gallaway, OD, Kristine Hopkins, OD, Brian G. Mohney, MD, Susanna Tamkins, OD

Clinical Sites

Sites are listed in order of the number of patients enrolled in the study with the number of patients enrolled is listed in parentheses preceded by the site name and location. Personnel are listed as (PI) for principal investigator, (SC) for coordinator, (E) for examiner, and (VT) for therapist.

Study Center: Bascom Palmer Eye Institute (35)

Susanna Tamkins, OD (PI); Hilda Capo, MD (E); Mark Dunbar, OD (E); Craig McKeown, MD (CO-PI); Arlanna Moshfeghi, MD (E); Kathryn Nelson, OD (E); Vicky Fischer, OD (VT); Adam Perlman, OD (VT); Ronda Singh, OD (VT); Eva Olivares (SC); Ana Rosa (SC); Nidia Rosado (SC); Elias Silverman (SC)

Study Center: SUNY College of Optometry (28)

Jeffrey Cooper, MS, OD (PI); Audra Steiner, OD (E, Co-PI); Marta Brunelli (VT); Stacy Friedman, OD (VT); Steven Ritter, OD (E); Lily Zhu, OD (E); Lyndon Wong, OD (E); Ida Chung, OD (E); Kaity Colon (SC)

Study Center: UAB School of Optometry (28)

Kristine Hopkins, OD (PI); Marcela Frazier, OD (E); Janene Sims, OD (E); Marsha Swanson, OD (E); Katherine Weise, OD (E); Adrienne Broadfoot, MS, OTR/L (VT, SC); Michelle Anderson, OD (VT); Catherine Baldwin (SC)

Study Center: NOVA Southeastern University (27)

Rachel Coulter, OD (PI); Deborah Amster, OD (E); Gregory Fecho, OD (E); Tanya Mahaphon, OD (E); Jacqueline Rodena, OD (E); Mary Bartuccio, OD (VT); Yin Tea, OD (VT); Annette Bade, OD (SC)

Study Center: Pennsylvania College of Optometry (25)

Michael Gallaway, OD (PI); Brandy Scombordi, OD (E); Mark Boas, OD (VT); Tomohiko Yamada, OD (VT); Ryan Langan (SC), Ruth Shoge, OD (E); Lily Zhu, OD (E)

Study Center: The Ohio State University College of Optometry (24)

Marjean Kulp, OD, MS (PI); Michelle Buckland, OD (E); Michael Earley, OD, PhD (E); Gina Gabriel, OD, MS (E); Aaron Zimmerman, OD (E); Kathleen Reuter, OD (VT); Andrew Toole, OD, MS (VT); Molly Biddle, MEd (SC); Nancy Stevens, MS, RD, LD (SC)

Study Center: Southern California College of Optometry (23)

Susan Cotter, OD, MS (PI); Eric Borsting, OD, MS (E); Michael Rouse, OD, MS (E); Carmen Barnhardt, OD, MS (VT); Raymond Chu, OD (VT); Susan Parker (SC); Rebecca Bridgeford (SC); Jamie Morris (SC); Javier Villalobos (SC)

Study Center: University of CA San Diego: Ratner Children's Eye Center (17)

David Granet, MD (PI); Lara Hustana, OD (E); Shira Robbins, MD (E); Erica Castro (VT); Cintia Gomi, MD (SC)

Study Center: Mayo Clinic (14)

Brian G. Mohney, MD (PI); Jonathan Holmes, MD (E); Melissa Rice, OD (VT); Virginia Karlsson, BS, CO (VT); Becky Nielsen (SC); Jan Sease, COMT/BS (SC); Tracee Shevlin (SC)

CITT Study Chair

Mitchell Scheiman, OD (Study Chair); Karen Pollack (Study Coordinator); Susan Cotter, OD, MS (Vice-Chair); Richard Hertle, MD (Vice-Chair); Michael Rouse, OD, MS (Consultant)

CITT Data Coordinating Center

Gladys Lynn Mitchell, MAS, (PI); Tracy Kitts, (Project Coordinator); Melanie Bacher (Programmer); Linda Barrett (Data Entry); Loraine Sinnott, PhD (Biostatistician); Kelly Watson (student worker); Pam Wessel (Office Associate)

National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD

Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH

CITT Executive Committee

Mitchell Scheiman, OD; G. Lynn Mitchell, MAS; Susan Cotter, OD, MS; Richard Hertle, MD; Marjean Kulp, OD, MS; Maryann Redford, DDS, MPH; Michael Rouse, OD, MSEd

Data and Safety Monitoring Committee

Marie Diener-West, PhD, Chair; Rev. Andrew Costello, CSsR; William V. Good, MD; Ron D. Hays, PhD; Argye Hillis, PhD (Through March 2006); Ruth Manny, OD, PhD

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00338611

REFERENCES

- 1.Scheiman M, Mitchell GL, Cotter S, Cooper J, Kulp M, Rouse M, Borsting E, London R, Wensveen J. A randomized clinical trial of treatments for convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:14–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. Randomized clinical trial of treatments for symptomatic convergence insufficiency in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126:1336–1349. doi: 10.1001/archopht.126.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wick B. Vision training for presbyopic nonstrabismic patients. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1977;54:244–247. doi: 10.1097/00006324-197704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patano FM. Orthoptic treatment of convergence insufficiency: a two year follow-up report. Am Orthop J. 1982;32:73–80. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen AH, Soden R. Effectiveness of visual therapy for convergence insufficiencies for an adult population. J Am Optom Assoc. 1984;55:491–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grisham JD, Bowman MC, Owyang LA, Chan CL. Vergence orthoptics: validity and persistence of the training effect. Optom Vis Sci. 1991;68:441–451. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199106000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borsting E, Rouse MW, De Land PN The Convergence Insufficiency and Reading Study (CIRS) Group. Prospective comparison of convergence insufficiency and normal binocular children on CIRS symptom surveys. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76:221–228. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199904000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borsting EJ, Rouse MW, Mitchell GL, Scheiman M, Cotter SA, Cooper J, Kulp MT, London R. Validity and reliability of the revised convergence insufficiency symptom survey in children aged 9 to 18 years. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80:832–838. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200312000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Convergence Insufficiency Treatment Trial Investigator Group. The convergence insufficiency treatment trial: design, methods, and baseline data. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15:24–36. doi: 10.1080/09286580701772037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sheard C. Zones of ocular comfort. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom. 1930;7:9–25. [Google Scholar]