Abstract

The ventricle of the salmonid heart consists of an outer compact layer of circumferentially arranged cardiomyocytes encasing a spongy myocardium that spans the lumen of the ventricle with a fine arrangement of muscular trabeculae. While many studies have detailed the anatomical structure of fish hearts, few have considered how these two cardiac muscle architectures are attached to form a functional working unit. The present study considers how the spindle-like cardiomyocytes, unlike the more rectangular structure of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes, form perpendicular connections between the two muscle layers that withstand the mechanical forces generated during cardiac systole and permit a simultaneous, coordinated contraction of both ventricular components. Therefore, hearts of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) and sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) were investigated in detail using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and various light microscopic techniques. In contrast to earlier suggestions, we found no evidence for a distinct connective tissue layer between the two muscle architectures that might ‘glue’ together the compact and the spongy myocardium. Instead, the contact layer between the compact and the spongy myocardium was characterized by a significantly higher amount of desmosome-like (D) and fascia adhaerens-like (FA) adhering junctions compared with either region alone. In addition, we observed that the trabeculae form muscular sheets of fairly uniform thickness and variable width rather than thick cylinders of variable diameter. This sheet-like trabecular anatomy would minimize diffusion distance while maximizing the area of contact between the trabecular muscle and the venous blood as well as the muscle tension generated by a single trabecular sheet.

Keywords: adhering junction, compact myocardium, desmosome, fascia adhaerens, fish heart, rainbow trout, sockeye salmon, spongy myocardium, trabeculation

Introduction

Salmonids are intensely studied in countries such as Canada, Norway and Scotland in the UK largely because of their great economic and ecological significance (Cooke et al. 2006). In addition, they are very important model systems for studying the evolution of the vertebrate cardiovascular system and comparative aspects of cardiac physiology (Farrell & Jones, 1992; Farrell, 2002; Shiels et al. 2002; Sandblom & Axelsson, 2007). More recently, it has been suggested that cardiac anatomy of salmon can be linked to their swimming performance (Claireaux et al. 2005) and that the cardiac performance may be the weak link in the tolerance of salmon to elevated temperature (Clark et al. 2008; Farrell et al. 2008; Steinhausen et al. 2008). Furthermore, veterinarian studies on farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) have shown that cardiac pathological diseases contribute to financial losses (Ferguson et al. 1990; Brun et al. 2003; Poppe et al. 2003). Therefore there is a broad interest in the anatomy, physiology and pathology of the salmonid heart.

Salmonids are characterized as being very athletic, with some species migrating thousands of kilometres and through difficult river rapids during their 3–5-year life history (Hinch et al. 2006). Such an athletic life style demands a cardiac structure that supports these activities. Therefore the salmonid ventricle shares features in common with other athletic fishes: it consists of an outer layer of circumferentially arranged cardiomyocytes (the compact myocardium) that encases a spongy myocardium, characterized by a fine arrangement of muscular trabeculae that span the lumen of the ventricle (termed a type-2 heart morphology; Tota, 1983; Davie & Farrell, 1991; Farrell & Jones, 1992). A similar anatomical arrangement is present during early developmental stages of avian and mammalian hearts (Sedmera et al. 2000). The trabeculae remaining prominent until the proportion of compact myocardium increases during late fetal and early neonatal development and the inner trabecular arrangements are reduced during the compaction process (Sedmera et al. 2000). Interestingly, a described malformation of the human myocardium is characterized by the pathologic disease state of ventricular ‘noncompaction’ (see Freedom et al. 2005; Hruda et al. 2005; Anderson, 2008) also referred to as a cardiomyopathic ‘persisting spongy myocardium’ (Dusek et al. 1975; Winer et al. 1998).

In contrast to the athletic fishes, it has been estimated that two thirds of all fish species lack a compact myocardium and have only one muscular architecture in their ventricle (which is termed a type-1 heart morphology; Santer, 1985).

During salmonid growth, the compact myocardial layer increases in amount and thickness (Poupa et al. 1974; Farrell et al. 1988), but rarely exceeds 50% of the total ventricular mass. Salmonids show considerable species-specific differences in life histories and habitats, including non-migratory (e.g. lake trout Salvelinus namaycush, or brown trout Salmo trutta) and anadromous (e.g. most of the salmon species), semelparous (e.g. most of the Pacific salmon species) and iteroparous species (e.g. Atlantic salmon Salmo salar or Pacific steelhead trout Oncorhynchus mykiss; see also Santer, 1985; Crespi & Teo, 2002). Species and intraspecific differences are emerging regarding both ventricular mass and the percentage of compact myocardium among salmonids and some of this variability appears to be related to the varying needs for athleticism. Interestingly, veterinarian studies of farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) revealed heart malformations characterized by a poor development or absence of the outer compact myocardium, resulting in circulatory disturbances in the affected fishes (Poppe & Taksdal, 2000). Fish that are more active than salmonids tend to have an even greater proportion of compact myocardium, exceeding 50% but never more than 75% of the total ventricular mass, such as bigeye tuna (Thunnus obesus), anchovy (Engraulis encrasicolus) and Pacific tarpon (Megalops pacificus; Santer & Greer-Walker, 1980; Farrell et al. 2007).

Despite the attention given to the general anatomical structure of fish hearts, no one to our knowledge has investigated how the two cardiac muscle layers in the salmonid heart ventricle might be connected to form a functional contractile chamber. We now know that unlike the rather rectangular structure of adult mammalian cardiomyocytes, fish cardiomyocytes are spindle-like with tapered ends (see e.g. Vornanen et al. 2002; Haverinen & Vornanen, 2007; Di Maio & Block, 2008). These tapered ends represent an obvious problem for a functional interaction between the spongy and compact cardiomyocytes because of their essentially perpendicular arrangement. Consequently, the present work considers how spindle-shaped cardiomyocytes of these two muscle layers form connections that withstand the mechanical forces generated during cardiac systole and permit coordinated contraction of both ventricular muscle components. With this aim, we investigated the distribution of adhering junctions between cardiomyocytes in ventricles of sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). In addition to detailed histological and scanning electron microscopic (SEM) observations, a comparison was made with hearts lacking a compact myocardium, such as hearts from tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus× mossambicus× hornorum) and the Pacific staghorn sculpin (Leptocottus armatus).

Our focus on the adhering junctions was founded on previous discoveries for mammalian ventricular cardiomyocytes, which are connected via bipolar organized intercalated disks (IDs) that are responsible for cell adhesion and force transmission during heart muscle contraction, as well as electrophysiological and metabolic coupling (Fawcett & McNutt, 1969; McNutt & Fawcett, 1969; Severs, 1989; Tandler et al. 2006; Shimada et al. 2004). Recent studies have revealed that IDs contain area composita adhering junctions (≥ 90% of the ID area) which represent mixed-type intercellular contacts composed of typical desmosomal and fascia adhaerens constituents (Borrmann et al. 2006; Franke et al. 2006, 2007; Goossens et al. 2007; Pieperhoff & Franke, 2007; Pieperhoff et al. 2008; for reviews see Holthöfer et al. 2007; Waschke, 2008). In contrast, cardiomyocytes of lower vertebrates are connected for the most part by separated, intermediate filament-binding desmosome-like and actin microfilament-binding fascia adhaerens-like adhering junctions (Pieperhoff & Franke, 2008). Although these junctions are typically organized on the lateral sides of each spindle-like cardiomyocyte of various amphibian and fish species, they occasionally resemble the mammalian mixed-type adhering junctions and some colocalization of typical desmosomal and fascia adhaerens proteins can occur (Franke et al. 2006; Pieperhoff & Franke, 2008).

The present study will help future analyses of cardiac structure–function relationships in fish (for zebrafish heart see also Hu et al. 2000), in particular those that consider cardiac muscle development and regeneration (Poss et al. 2002; Ausoni & Sartore, 2009; Martin et al. 2009).

Materials and methods

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka, ± 100 g, n = 10); rainbow trout (Oncorynchus mykiss, ± 150 g, n = 10), tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus× mossambicus× hornorum, ± 500 g, n = 4) and Pacific staghorn sculpin (Leptocottus armatus, 120–270 g, n = 4) were sacrificed by percussion to the forehead. The hearts were immediately dissected and perfused with isotonic buffer to rinse out blood before being perfusion fixed using 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 1.6% formaldehyde in isotonic 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer. Each whole heart was then incubated for another 4 h in the same fixative before being cut in half with a sharp razor blade and left overnight to fix completely. The specimens were post-fixed in three steps using sodium cacodylate buffered 2% osmium tetroxide, followed by aqueous thiocarbohydrazide (TCH) and then 2% aqueous osmium tetroxide, each for 30 min. The heart specimens were dehydrated in an ethanol series, followed by a gradual exchange of the highest ethanol concentration by hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS), drying, mounting on stubs and coating with a 12-nm layer of gold particles using a sputter coater (Cressington, Watford, UK). Images were obtained using a Hitachi S-2600N Variable Pressure Scanning Electron Microscope (VPSEM, Hitachi High-Technologies, Toronto, ON, Canada).

Histology and light microscopy

All fish were killed as described above. Hearts from mature sockeye salmon (3–4 kg, n = 20), rainbow trout (± 300 g, n = 10), tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus× mossambicus×hornorum, ± 500 g, n= 2) and Pacific staghorn sculpin (Leptocottus armatus, 120–270 g, n= 2) were cut in half and fixed in 10% acetate buffered formalin (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada). They were subsequently dehydrated in an ethanol series and embedded in paraffin wax. Paraffin tissue blocks were sectioned at 5–8 μm and sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome (Masson, 1929) to differentiate between connective tissue and muscle tissue. Sirius red staining of extracellular matrix material such as collagen bundles was performed as described by Puchtler et al. (1964) and Llewellyn (1970). Images were taken using an Axioplan 2 wide field imaging microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) in combination with a 12-bit, cooled CCD camera (QImaging, Surrey, Canada).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described previously (Pieperhoff & Franke, 2007, 2008). Frozen tissues from all four fish species were examined. Immunofluorescence labelling was performed using monoclonal antibodies specific for either the desmosomal plaque protein, desmoplakin (murine mAb, clone DP447; Progen Biotechnik, Heidelberg, Germany), or for fascia adhaerens markers such as N-cadherin (mAb clone 32, BD Biosciences Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany) in addition to an antibody specific for plakoglobin (clone PG 5.1.; Progen Biotechnik), known to be a plaque protein of both types of adhering junctions (Cowin et al. 1986; Franke et al. 1989).

Trout cardiomyocyte were prepared as described by Vornanen (1998). The cells were fixed for 10 min in 10% acetate buffered formalin and stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol (DAPI; Serva, Heidelberg) as described previously (Pieperhoff et al. 2008).

Results

Scanning electron microscopy

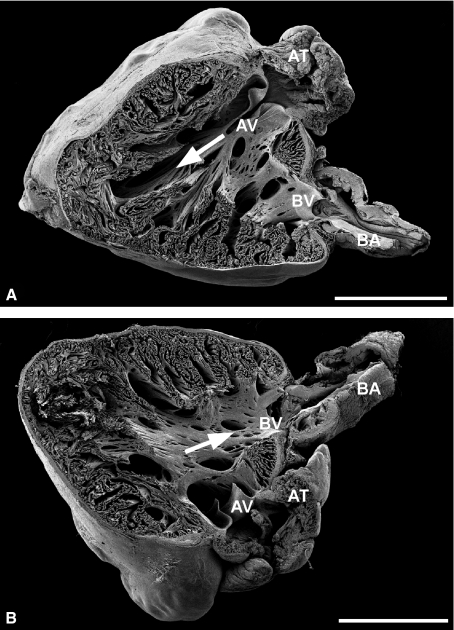

As clearly seen in Fig. 1, the sockeye salmon heart has a pyramidal shape. The atrium (AT), the atrioventricular valve (AV), the single ventricle, the bulboventricular valve (BV; also suggested to be called conus valve; Icardo, 2006) and the bulbus arteriosus (BA) are visible (for cardiac valves in other fish species see e.g. Sans-Coma et al. 1995; Icardo et al. 2003; for mammalian cardiac valves see e.g. Icardo et al. 1993; Icardo & Colvee, 1995a,b; for adhering junctions connecting interstitial cells of mammalian cardiac valves see Barth et al. 2009). Blood flow directions are indicated by arrows for diastolic filling from the atrium (Fig. 1A) and for systolic emptying to the bulbus (Fig. 1B). The compact myocardium encases the spongy myocardium and contains coronary vessels (arrows in Fig. 2). However, due to a processing artefact the compact myocardium occasionally detached focally from the spongy myocardium (Fig. 2B). Such detachments revealed a clear and very thin but continuous layer of cardiomyocytes, probably not more than one or two cell layers thick, associated with the outer spongy myocardium (Fig. 2A, B). We interpret this layer as being formed by the spindle-like cardiomyocytes of the trabeculae terminally bending to various degrees to form this continuous layer. Similar findings were made for rainbow trout hearts of slightly smaller size (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Scanning electron micrographs show left (A) and right (B) half of the same adult sockeye salmon heart. (A,B) Highly trabeculated inner spongy and the outer compact myocardium (better seen in Fig. 2). The highly organized trabecular arrangements recess intratrabecular pockets and a trabeculae-free lumen allowing fast directed blood in (arrow in A) and outflow (see arrow in B). AT, atrium; BA, bulbus arteriosus; AV, atrioventricular valve; BV, bulboventricular valve; bars: 2 mm.

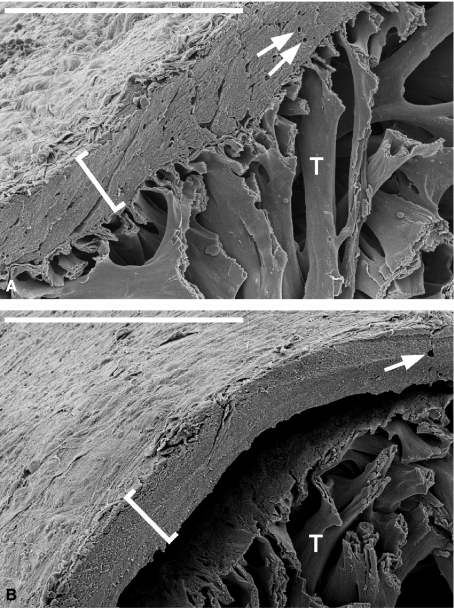

Fig. 2.

Higher magnification scanning electron micrograph of the dorsal part (apex) of the left half of a sockeye salmon heart (see also Fig. 1A). (A) Highlights the composition of the salmonid heart and clearly shows the existence of two different muscular systems (compact and spongy myocardium) directly attached to each other. The trabeculae seem to bend in two directions to allow the lateral connection of the spindle-like fish cardiomyocytes to the outer compact myocardium (compare with Fig. 6). (B) Due to processing of the heart tissue the spongy myocardium is somewhat detached from the compact myocardium in a defined area, supporting the idea of a weak point in this attachment region. Note the clearly separated spongy and compact myocardium in (B) and that the trabecular arrangements seem to bend to attach to the compact myocardium in (A; compare with Fig. 6). Brackets: compact myocardium, T: trabeculae of spongy myocardium, arrows indicate the coronary blood vessels (in this case small capillaries), bars: 200 μm.

The network of trabecular muscle fibers in the sockeye salmon ventricle shows several important features. Intratrabecular pockets are clearly recessed, resulting in distinct portions of the lumen that are trabecula-free, as similarly shown for frog hearts (Sedmera et al. 2000). Also, the trabeculae span almost the entire inner spongy layer in both halves of the salmon heart (see Figs 1–3A). In addition, individual trabeculae can attain an impressive size (Figs 1–3), but usually appear as a flat sheet of cardiomyocytes that has a limited depth and a variable, sometimes large, width (Fig. 3). This sheet-like tissue arrangement could provide advantages for directing blood flow by increasing the cross-sectional area of an individual trabecula to improve tension development without greatly increasing the maximal diffusion distance.

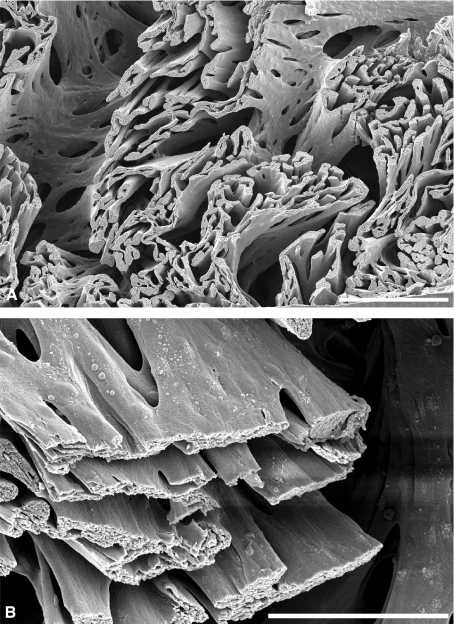

Fig. 3.

(A) Trabecular arrangements in the inner spongy myocardium of the sockeye salmon heart forming channel-like structures to allow directed blood flow; the trabeculae often seem to be flattened to minimize diffusion distance. (B) Higher magnification of several flattened trabeculae. Bar in (A) 250 μm, bar in (B) 100 μm.

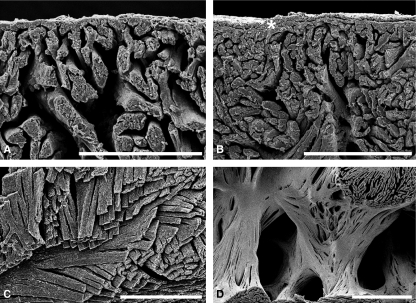

The ventricles from tilapia and Pacific staghorn sculpin obviously exhibit no compact myocardium, but the cardiomyocyte arrangements still seem to bend to build a thin, outer layer (e.g. Fig. 4; for another species see also Icardo et al. 2005). The sheet-like appearance of trabeculae was less evident in the spongy myocardium of tilapia and Pacific staghorn sculpin (Fig. 4C), with the result that in these species the depth of individual trabeculae was slightly greater than in sockeye salmon. However, variations in individual age and body size (see Material and methods) could easily contribute to such dimensional differences.

Fig. 4.

Scanning electron micrograph of a tilapia heart (A,C) and sculpin heart (B,D) longitudinal section. (A,B) Note the complete absence of an outer compact myocardium (compare with Fig. 2). The epicardium denoted by an asterisk in (B) may often be detached during tissue processing (A). The trabeculae form flattened cardiomyocyte arrangements of increased width but constant depth (see in C–D) in both hearts exhibiting no pronounced compact myocardium. Bars in (A,B) 100 μm, bar in (C) 250 μm, bar in (D) 500 μm.

Histology

Sections through the paraffin-embedded hearts of sockeye salmon, rainbow trout (data not shown) and tilapia were stained with Masson’s trichrome to differentiate connective tissue from cardiac muscle tissue (see Fig. 5A,B). In the mature sockeye salmon heart, the compact and the spongy myocardium were easily discernible and were directly apposed with each other, without an intervening distinctive layer of connective tissue (Fig. 5A). In contrast, connective tissue elements (blue staining patterns) are clearly defined in the outer epicardium and alongside a large coronary vessel filled with nucleated red blood cells (asterisk). Similar findings were made for rainbow trout (data not shown). Pronounced intramyocardial extracellular matrix material or interstitial connective tissue was observed in the tilapia ventricle and more infrequently in the salmonid ventricles (Fig. 5B; see also Sanchez-Quintana et al. 1996), which usually increases with age (as described by Santer, 1985). In contrast, the tilapia heart lacked a compact myocardium and, similar to the salmon ventricle, the epicardium contained a distinctive connective tissue layer (outer blue staining pattern, see Fig. 5B).

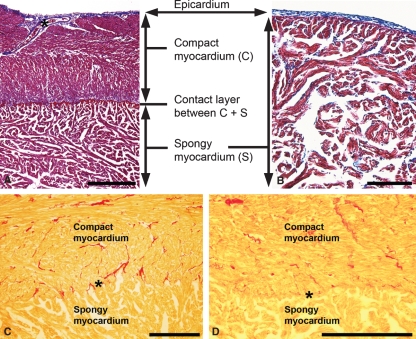

Fig. 5.

Light microscopic images of Masson’s trichrome stained (A, B) and Sirius red stained (C,D) paraffin sections through the adult sockeye salmon heart (A,C), through the tilapia heart (B) and through the rainbow trout heart (D). Note the blue staining (A,B) of the connective tissue as a part of the outermost epicardium, a coronary vessel surrounded by connective tissue (asterisk in A) and the dark-red trichrome staining pattern of the heart muscle tissue. Intramyocardial connective tissue is stained with the two different staining techniques (blue in A,B; red in C,D). The pronounced compact myocardium (C) in the mature sockeye salmon heart (A) is obviously absent in the tilapia heart (B). Using Sirius red staining technique, extracellular matrix material (such as collagen, red) can be seen sparsely dispersed throughout the sockeye salmon (C) and rainbow trout (D) ventricles. Occasionally such material is enriched, but it is discontinuous in the area where the compact and the spongy myocardium are attached (asterisks in C and D). No pronounced continuous connective tissue layer separating the two muscular architectures was observed with either staining technique. Bar in (A) 4 mm, bar in (B) 1 mm, bars in (C,D) 100 μm.

Sirius red staining, which specifically stains extracellular matrix material such as collagen fibres, revealed similar results as the Masson’s trichrome stain. Intramyocardial extracellular matrix material was dispersed sparsely throughout the salmonid ventricle (Fig. 5C,D), often located close to coronary blood vessels of various sizes. Occasionally, intramyocardial extracellular matrix material was enriched at the junction of trabeculae and compact myocardium (Fig. 5C).

Immunofluorescence microscopy

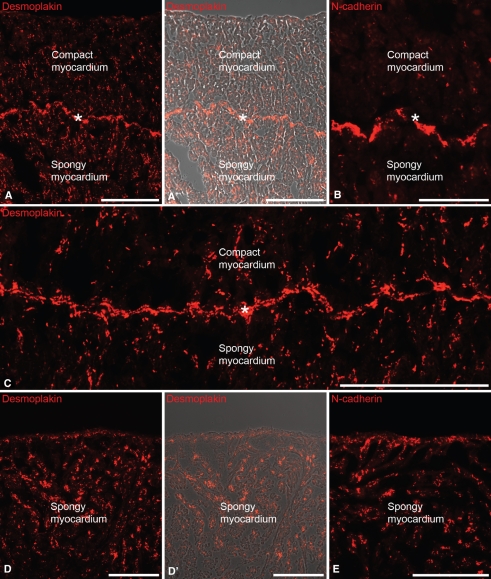

The spatial distribution of typical desmosomal markers, such as the desmosomal plaque protein desmoplakin (Franke et al. 1981; Cowin et al. 1985) and typical fascia adhaerens markers such as N-cadherin (Geiger et al. 1983; Volk & Geiger, 1984), were investigated in the four fish species. In the past such studies were limited by the fact that almost no fish-reactive or fish-specific antibodies existed for these adhering junction constituents. However, we used recently generated monoclonal and polyclonal antibodies that are reactive with these junctional proteins (Pieperhoff & Franke, 2008) to localize desmosome-like (positive for desmoplakin) and fascia adhaerens-like (positive for N-cadherin) junctions, with a special focus on the border between the compact and spongy myocardium in the salmonid ventricle. Both markers were evenly distributed throughout both the spongy and the compact myocardia (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, we observed a distinct and continuous local enrichment of desmoplakin and N-cadherin immunofluorescence staining in junctions located at the border between the compact and spongy myocardia (asterisks in Fig. 6A–C).

Fig. 6.

Immunofluorescence micrographs of cryostat sections through the sockeye salmon heart (A,B), rainbow trout heart (C) and tilapia heart (D,E). Shown are immunofluorescence micrographs using a monoclonal antibody specific for the desmosomal plaque protein desmoplakin (A,A’,C,D,D’) and the fascia adhaerens protein N-cadherin (B,E). (A’,D’) Merged phase contrast images of (A,D). Note the significantly high amount of desmoplakin-positive and N-cadherin-positive adhering junctions located in the contact layer of compact and spongy myocardium (asterisks). Bars in (A,C–E) 100 μm; bar in (B) 50μm.

In tilapia and sculpin hearts both junctional constituents showed an even distribution throughout the spongy myocardium (Fig. 6D,E). Occasionally a moderate enrichment of both junction components was observed in the outermost cardiac muscle layer (see Fig. 6E).

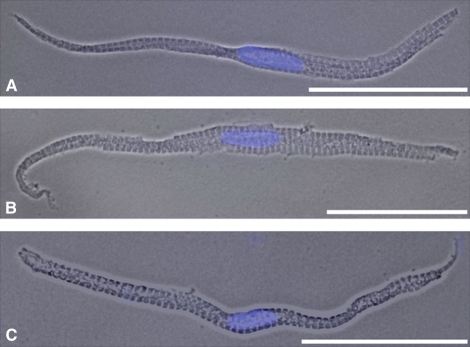

Phase contrast images of isolated trout cardiomyocytes showed their spindle-like shape and the clearly stained nuclei (DAPI staining, blue; compare Fig. 7 with Fig. 8). The surface of the cardiomyocytes was slightly ragged in appearance, which may be explained by incubating too long in the isolation or digestion solution (i.e. an ‘overdigestion’ artefact).

Fig. 7.

(A–C) Light microscopic phase contrast images of different isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes of rainbow trout shown with merged DAPI staining of the nucleus (blue). Note the spindle-like but slightly different shapes and the tapered ends of the different cardiomyocytes shown. The cells look slightly ragged, which might be explained by overdigestion. Bars: 50 μm.

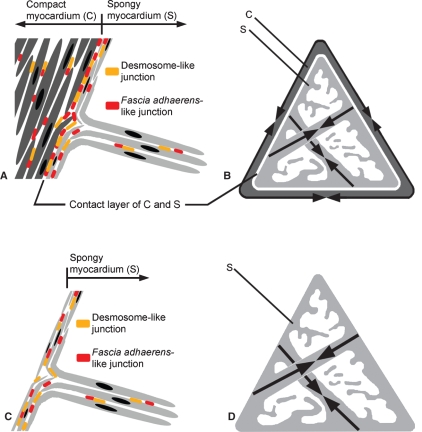

Fig. 8.

(A–D) Scheme indicating the hypothetical cardiomyocyte arrangements, adhering junction localizations and muscle contraction directions (arrows in B,D) in the pyramidal- shaped fish ventricle (drawn in cross-sectional view) exhibiting a compact myocardium and a spongy myocardium (A,B) and for those exhibiting only a spongy myocardium (C,D). The spindle-like cardiomyocytes might bend to laterally attach to the outer compact myocardium and most of the desmosome-like and fascia adhaerens-like junctions are localized where the two heart muscle systems are connected (A; compare with Fig. 6). In the fish heart without any compact myocardium, occasionally a slightly larger number of adhering junctions may be localized in the outer portion of the myocardium where single trabeculae are connected (C; compare with Fig. 6E). Species-specific differences may occur and will have to be investigated in future analyses.

Discussion

Interestingly, throughout this study we observed only small amounts of intramyocardial extracellular matrix material and connective tissue elements in the fish ventricle (e.g. Fig. 5; see also Sanchez-Quintana et al. 1996). The exception was the focal material associated with coronary blood vessels and the epicardium. Nevertheless, there are some reports and suggestions of a connective tissue layer separating the two muscular systems (e.g. Poupa et al. 1974; Tota, 1978), which would be easy to envisage as acting as the ‘glue’ for the necessary associations of the two different muscular architectures. Here we provide several lines of evidence that lead us to reject this concept. The most critical piece of evidence is the simple fact that we did not detect a distinct, continuous, intervening connective tissue layer in the sockeye salmon and rainbow trout ventricle (Fig. 5), despite the fact that the two staining techniques readily identified a band of connective tissue in the epicardial layer of all four fish species, as also stated by Santer (1985). Intramyocardial connective tissue or extracellular matrix material was occasionally and intermittently enriched in the border area of the spongy and the compact myocardium (especially in mature salmon; see Sirius red staining in Fig. 5C,D).

In the absence of a pronounced connective tissue, an architectural mechanism has to be advanced to explain how spindle-shaped transluminal cardiomyocytes organized in the trabeculae of the spongy myocardium can firmly attach to the circumferentially arranged cardiomyocytes of the compact myocardium. We suggest that the outer cardiomyocytes of the spongy myocardium may bend to a certain degree at their tips to create a parallel attachment surface. These bent tips would serve for attachment with either the encasing outer compact muscular system in salmonid ventricles or with the outer cardiomyocytes of the tilapia and Pacific staghorn sculpin ventricles (Fig. 8). Support for this idea comes from light microscopic and scanning electron microscopic observations in these border areas of salmonid (Figs 2A and 5A), tilapia and Pacific staghorn sculpin ventricles (Figs 4A,B and 5B; compare to Fig. 8).

We further envisage that while contraction of the circumferentially arranged compact myocardium acts as a muscle system that functionally compresses the volume of the ventricle, the transluminal trabeculae represent a separate but coordinated muscular system that act as contractile ‘girders’ pulling the compact myocardium inwards during contraction. In other words, the directional vector for contraction of the compact myocardium and the spongy myocardium differs (Fig. 8B). Without bent ends, contracting trabeculae would act on specific focal points of the compact myocardium, which would greatly increase the force per unit area generated. Obviously, a greater area of contact as a result of bent myocyte ends at the border area would not only reduce the force per unit area to prevent separation of the two muscular architectures, but would also increase the potential surface area where intercellular adhering junctions can be located (see Fig. 2A; compare with Fig. 8A; this proposed scheme could perhaps work equally well if the myocyctes in the compact myocardial layer were similarly bent to line up with trabecular myocytes, see Fig. 8). Under such an anatomical scheme, it is perhaps no surprise that the border area has a distinct and impressive band of enrichment of desmosome-like structures positive for desmoplakin immunostaining (Fig. 6A,C) and fascia adhaerens-like elements positive for N-cadherin immunostaining (Fig. 6B). Most cardiomyocytes in the compact and spongy myocardium are for the most part laterally connected by adhering junctions, as reported previously for various teleost fish and amphibian species (Pieperhoff & Franke, 2008). The parallel cardiomyocytes in the border region allow lateral cell adhesion via both types of cadherin-mediated cardiac adhering junctions known to be responsible for ‘robust’ cell adhesion and force transmission during heart muscle contraction (Pieperhoff & Franke, 2008). This combination of both types of muscle architectures via densely packed cardiomyocytes exhibiting high amounts of intermediate filament-binding desmosomes and actomyosin filament-binding fasciae adhaerentes may also be prominent in other athletic fishes with even higher amounts of compact myocardium such as tuna, anchovy or shark (Tota, 1983; Davie & Farrell, 1991) which need to be included in future investigations. The sparse enrichment of intramyocardial extracellular matrix material in the border area may have an important additional supporting function (see Fig. 5C).

Despite the clear enrichment of adhering junctions in the layer between the compact and the spongy myocardium of the salmonid heart, this region must still be considered a potential weak linkage in this type of lower vertebrate heart morphology. Foremost, the two layers often spontaneously separated during SEM preparation, although we do not know why this occurred. Moreover, the two layers can be easily separated in tissue fixed in 70% ethanol, as has recently been recognized when estimating the relative proportions of compact and spongy myocardium (Farrell et al. 2007). After fixation, the compact layer could be peeled off the spongy myocardium. Previously, it was suggested that the ease with which this was possible can be explained by the presence of an intervening layer of connective tissue. However, this is certainly not the case for the salmonid ventricle based on the present results. Interestingly, the hearts of dogfish (Scyliorhinus canicula) and tuna (Thunnus thunnus) are less amenable to this peeling technique (Farrell et al. 2007). Whether this difficulty reflects a more robust intercellular adhering junctional system between the two types of muscle architectures, or both types are to some degree ‘interwoven’, is unclear. However, these species-specific differences are certainly worthy of further studies, and future experiments controlling the preparative steps by transmission electron microscopy will be needed.

Another important discovery made here for the salmonid ventricle is that the trabecular network both is highly organized and tends to span the inner wall of the myocardium to varying degrees (see Fig. 1, for other teleost hearts see Munshi et al. 2001; Icardo et al. 2005). The resulting trabecula-free lumen, as already shown for frog hearts (Sedmera et al. 2000) and other teleost species (see e.g. Hu et al. 2000; Munshi et al. 2001; Icardo et al. 2005), may allow a more directional and controlled inflow and outflow of blood (see arrows in Fig. 1), at the same time reducing the frictional resistance to blood flow as compared with a more trabecular arrangement. Furthermore, trabeculae that act as contractile girders may facilitate the high ejection fraction (about 77%) that is characteristic of the rainbow trout heart (Franklin & Davie, 1992), as compared with the adult mammalian heart (about 50–65%) with its more defined lumen that largely lacks trabeculae. Indeed, a potential reason for the retention of a spongy myocardium in all fish (i.e. compact myocardium never exceeds 70% of ventricular mass) may be necessary for a very high ejection fraction to void the heart almost entirely of the venous blood during each systolic contraction, and allow as much fresh blood as possible to enter with each heart beat.

Fish ventricles appear to grow isometrically with body mass (Farrell et al. 1988). As a result, both the compact and the spongy myocardia increase in mass, despite a disproportionately greater increase in compact myocardium. The compact myocardium simply increases its thickness and coronary vascularity. However, the spongy myocardium must increase the number of trabeculae and their cross-sectional area. The general problem of an excessive oxygen diffusion distance for cardiac trabeculae, which obtain oxygen by diffusion from the venous blood, has already been noted (e.g. Davie & Farrell, 1991; O’Brien et al. 2000; and references cited therein). Rather than thicker, rounded trabeculae, we observed that the spongy cardiomyocytes associate laterally to form flattened trabecular sheets (best seen in the cross-section of Fig. 3; see also Figs 1, 2, 4; for other fish species see Munshi et al. 2001; Icardo et al. 2005). By adopting a sheet-like arrangement, muscle tension development can be increased while at the same time keeping oxygen diffusion distance to a minimum. The width of trabecular arrangements is very variable and trabeculae can form an impressive surface area (Fig. 1) that may exceed a couple of hundreds micrometers. Even so, both the sheet-like and the smaller, more cylindrical trabeculae usually had thicknesses between 20 and 25 μm.

Future investigations of hearts from specific stages of mammalian development may be interesting as a result of the present study and therefore these will be systematically re-investigated (for antecedent studies see Pieperhoff & Franke, 2007). These hearts, in addition to those of other athletic fish species such as tuna, anchovy and shark (as already noted in hearts of the European eel; Anguilla anguilla; data not shown), might exhibit similar arrangements of adhering junctions between the outer myocardium and the inner trabecular network as found here for the salmonid ventricles. This might also be the case for hearts of human cases of ventricular noncompaction characterized by a persistent extensive trabecular network attached to the compact portion of the ventricular wall (see especially Freedom et al. 2005; Anderson, 2008; and references cited therein).

Conclusion

We conclude that the spongy and the compact myocardium are connected primarily and directly by intermediate filament-binding desmosome-like and actomyosin filament-binding fascia adhaerens-like adhering junctions. Similar arrangements of adhering junctions may be found in hearts of specific stages in mammalian development or in hearts from human cases of ventricular noncompaction. Moreover, we reject the idea that a distinct and an extensive connective tissue layer acts as a functional interface between the compact myocardium and the spongy myocardium in the salmonid ventricle. Instead, we confirmed an enrichment of intramyocardial and discontinuous connective tissue in close proximity to the area where the two different muscle architectures are attached. We propose that the junctional interface at the border of the two muscle architectures features bent ends of the spindle-shaped cardiomyocytes of the spongy myocardium that allow for regions of tight, parallel arrangements of cardiomyocytes. In addition, in the ventricles of all the observed fish hearts, trabeculae increase their cross-sectional area by increasing their width and perhaps maintaining their depth. This sheet-like structure increases the ability to develop wall tension without greatly increasing the diffusion distance for trabeculae to receive oxygen from venous blood.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Kevin Hodgson, Derrick Horne and Garnet Martens from the UBC Bioimaging Center (Vancouver, Canada) for their very helpful and constant support during this study and to Christopher M. Wilson (this group) for help with the preparation of trout cardiomyocytes. Further thanks go to Jayme Hills, Miki Nomura and David A. Patterson from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, Canada) for providing us with numerous sockeye salmon tissue samples and to Dr. Jeff Richards and Ben Speers-Roesch (University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada) for providing living tilapia and sculpin fish for this study. The authors thank Prof. Werner W. Franke (German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany) for encouragement and discussions. S.P. herewith thanks in particular the Canadian Government (DFAIT) for funding of a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (PDRF) during the tenure 03/2008–03/2009 and the German Science Foundation (DFG) for funding of a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship during the following tenure 04/2009-04/2011. A.P.F. is supported by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

References

- Anderson RH. Ventricular non-compaction – a frequently ignored finding? Eur Heart J. 2008;29:10–11. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausoni S, Sartore S. From fish to amphibians to mammals: in search of novel strategies to optimize cardiac regeneration. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:357–364. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200810094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth M, Schumacher H, Kuhn C, et al. Cordial connections: molecular ensembles and structures of adhering junctions connecting interstitial cells of cardiac valves in situ and in cell culture. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;337:63–77. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0806-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrmann CM, Grund C, Kuhn C, et al. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. II. Colocalizations of desmosomal and fascia adhaerens molecules in the intercalated disk. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:469–485. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brun E, Poppe T, Skrudland A, et al. Cardiomyopathy syndrome in farmed Atlantic salmon Salmo salar: occurrence and direct financial losses for Norwegian aquaculture. Dis Aquat Organ. 2003;56:241–247. doi: 10.3354/dao056241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claireaux G, McKenzie DJ, Genge AG, et al. Linking swimming performance, cardiac pumping ability and cardiac anatomy in rainbow trout. J Exp Biol. 2005;208:1775–1784. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TD, Sandblom E, Cox GK, et al. Circulatory limits to oxygen supply during an acute temperature increase in the Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;295:R1631–R1639. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90461.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke SJ, Hinch SG, Crossin GT, et al. Mechanistic basis of individual mortality in Pacific salmon during spawning migrations. Ecology. 2006;87:1575–1586. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1575:mboimi]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Kapprell HP, Franke WW. The complement of desmosomal plaque proteins in different cell types. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:1442–1454. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.4.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowin P, Kapprell HP, Franke WW, et al. Plakoglobin: a protein common to different kinds of intercellular adhering junctions. Cell. 1986;46:1063–1073. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90706-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespi BJ, Teo R. Comparative phylogenetic analysis of the evolution of semelparity and life history in salmonid fishes. Evolution. 2002;56:1008–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2002.tb01412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davie PS, Farrell AP. The coronary and luminal circulations of the myocardium of fishes. Can J Zool. 1991;69:1993–2001. [Google Scholar]

- Di Maio A, Block BA. Ultrastructure of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in cardiac myocytes from Pacific bluefin tuna. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;334:121–134. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0669-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusek J, Ostadal B, Duskova M. Postnatal persistence of spongy myocardium with embryonic blood supply. Arch Pathol. 1975;99:312–317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP. Cardiorespiratory performance in salmonids during exercise at high temperature: insights into cardiovascular design limitations in fishes. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2002;132:797–810. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP, Jones DR. Fish Physiology. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP, Hammons AM, Graham MS, et al. Cardiac growth in rainbow trout, Salmo gairdneri. Can J Zool. 1988;66:2368–2373. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP, Simonot DL, Seymour RS, et al. A novel technique for estimating the compact myocardium in fish reveals surprising results for an athletic air-breathing fish, the Pacific tarpon. J Fish Biol. 2007;71:389–398. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AP, Hinch SG, Cooke SJ, et al. Pacific salmon in hot water: applying aerobic scope models and biotelemetry to predict the success of spawning migrations. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2008;81:697–708. doi: 10.1086/592057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett DW, McNutt NS. The ultrastructure of the cat myocardium. I. Ventricular papillary muscle. J Cell Biol. 1969;42:1–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson HW, Poppe T, Speare DJ. Cardiomyopathy in farmed Norwegian salmon. Dis Aquat Organ. 1990;8:225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Franke WW, Schmid E, Grund C, et al. Antibodies to high molecular weight polypeptides of desmosomes: specific localization of a class of junctional proteins in cells and tissue. Differentiation. 1981;20:217–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1981.tb01178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke WW, Goldschmidt MD, Zimbelmann R, et al. Molecular cloning and amino acid sequence of human plakoglobin, the common junctional plaque protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:4027–4031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.11.4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke WW, Borrmann CM, Grund C, et al. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. I. Molecular definition in intercalated disks of cardiomyocytes by immunoelectron microscopy of desmosomal proteins. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke WW, Schumacher H, Borrmann CM, et al. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates – III: assembly and disintegration of intercalated disks in rat cardiomyocytes growing in culture. Eur J Cell Biol. 2007;86:127–142. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin CE, Davie PS. Dimensional analysis of the ventricle of an in situ perfused trout heart using echocardiography. J Exp Biol. 1992;166:47–60. doi: 10.1242/jeb.166.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedom RM, Yoo SJ, Perrin D, et al. The morphological spectrum of ventricular noncompaction. Cardiol Young. 2005;15:345–364. doi: 10.1017/S1047951105000752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger B, Schmid E, Franke WW. Spatial distribution of proteins specific for desmosomes and adhaerens junctions in epithelial cells demonstrated by double immunofluorescence microscopy. Differentiation. 1983;23:189–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1982.tb01283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens S, Janssens B, Bonne S, et al. A unique and specific interaction between alphaT-catenin and plakophilin-2 in the area composita, the mixed-type junctional structure of cardiac intercalated discs. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2126–2136. doi: 10.1242/jcs.004713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverinen J, Vornanen M. Temperature acclimation modifies sinoatrial pacemaker mechanism of the rainbow trout heart. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1023–R1032. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00432.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinch SG, Cooke SJ, Healey MC, et al. Behavorial physiology of fish migrations: Salmon as a model approach. In: Sloman KA, Wilson RW, Balshine S, editors. Behaviour and Physiology of Fish, Vol. 24. San Diego: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 239–295. [Google Scholar]

- Holthöfer B, Windoffer R, Troyanovsky S, et al. Structure and function of desmosomes. Int Rev Cytol. 2007;264:65–163. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)64003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruda J, Sobotka-Plojhar MA, Fetter WP. Transient postnatal heart failure caused by noncompaction of the right ventricular myocardium. Pediatr Cardiol. 2005;26:452–454. doi: 10.1007/s00246-004-0752-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu N, Sedmera D, Yost HJ, et al. Structure and function of the developing zebrafish heart. Anat Rec. 2000;260:148–157. doi: 10.1002/1097-0185(20001001)260:2<148::AID-AR50>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM. Conus arteriosus of the teleost heart: dismissed, but not missed. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:900–908. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM, Colvee E. Atrioventricular valves of the mouse: II. Light and transmission electron microscopy. Anat Rec. 1995a;241:391–400. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092410314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM, Colvee E. Atrioventricular valves of the mouse: III. Collagenous skeleton and myotendinous junction. Anat Rec. 1995b;243:367–375. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092430311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM, Arrechedera H, Colvee E. The atrioventricular valves of the mouse. I. A scanning electron microscope study. J Anat. 1993;182(Pt 1):87–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM, Schib JL, Ojeda JL, et al. The conus valves of the adult gilthead seabream (Sparus auratus) J Anat. 2003;202:537–550. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2003.00186.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Icardo JM, Imbrogno S, Gattuso A, et al. The heart of Sparus auratus: a reappraisal of cardiac functional morphology in teleosts. J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol. 2005;303:665–675. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llewellyn BD. An improved Sirius red method for amyloid. J Med Lab Technol. 1970;27:308–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin ED, Moriarty MA, Byrnes L, et al. Plakoglobin has both structural and signalling roles in zebrafish development. Dev Biol. 2009;327:83–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masson PJ. Some histological methods. Trichrome stainings and their preliminary technique. J Techn Methods. 1929;12:75–90. [Google Scholar]

- McNutt NS, Fawcett DW. The ultrastructure of the cat myocardium. II. Atrial muscle. J Cell Biol. 1969;42:46–67. doi: 10.1083/jcb.42.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munshi JSD, Olson KR, Roy PK, et al. Scanning electron microscopy of the heart of the climbing perch. J Fish Biol. 2001;59:1170–1180. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien KM, Xue H, Sidell BD. Quantification of diffusion distance within the spongy myocardium of hearts from antarctic fishes. Respir Physiol. 2000;122:71–80. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(00)00139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieperhoff S, Franke WW. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. IV. Coalescence and amalgamation of desmosomal and adhaerens junction components – late processes in mammalian heart development. Eur J Cell Biol. 2007;86:377–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieperhoff S, Franke WW. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. VI. Different precursor structures in non-mammalian species. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:413–430. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieperhoff S, Schumacher H, Franke WW. The area composita of adhering junctions connecting heart muscle cells of vertebrates. V. The importance of plakophilin-2 demonstrated by small interference RNA-mediated knockdown in cultured rat cardiomyocytes. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppe TT, Taksdal T. Ventricular hypoplasia in farmed Atlantic salmon Salmo salar. Dis Aquat Organ. 2000;42:35–40. doi: 10.3354/dao042035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppe TT, Johansen R, Gunnes G, et al. Heart morphology in wild and farmed Atlantic salmon Salmo salar and rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Dis Aquat Organ. 2003;57:103–108. doi: 10.3354/dao057103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298:2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1077857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poupa O, Gesser H, Jonsson S, et al. Coronary-supplied compact shell of ventricular myocardium in salmonids: growth and enzyme pattern. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1974;48:85–95. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(74)90856-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puchtler H, Sweat F, Kuhns JG. On the binding of direct cotton dyes by amyloid. J Histochem Cytochem. 1964;12:900–907. doi: 10.1177/12.12.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Quintana D, García-Martínez V, Climent V, et al. Myocardial fiber and connective tissue architecture in the fish heart ventricle. J Exp Zool. 1996;275:112–124. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(11)80198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandblom E, Axelsson M. Venous hemodynamic responses to acute temperature increase in the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R2292–R2298. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00884.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans-Coma V, Gallego A, Munoz-Chapuli R, et al. Anatomy and histology of the cardiac conal valves of the adult dogfish (Scyliorhinus canicula) Anat Rec. 1995;241:496–504. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092410407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santer RM. Morphology and innervation of the fish heart. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 1985;89:1–102. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-70135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santer RM, Greer-Walker M. Morphological studies on the ventricle of teleost and elasmobranch hearts. J Zool. 1980;190:259–272. [Google Scholar]

- Sedmera D, Pexieder T, Vuillemin M, et al. Developmental patterning of the myocardium. Anat Rec. 2000;258:319–337. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(20000401)258:4<319::AID-AR1>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severs NJ. Gap junction shape and orientation at the cardiac intercalated disk. Circ Res. 1989;65:1458–1462. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.5.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiels HA, Vornanen M, Farrell AP. Temperature dependence of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum function in rainbow trout myocytes. J Exp Biol. 2002;205:3631–3639. doi: 10.1242/jeb.205.23.3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Kawazato H, Yasuda A, et al. Cytoarchitecture and intercalated disks of the working myocardium and the conduction system in the mammalian heart. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2004;280:940–951. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen MF, Sandblom E, Eliason EJ, et al. The effect of acute temperature increases on the cardiorespiratory performance of resting and swimming sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) J Exp Biol. 2008;211:3915–3926. doi: 10.1242/jeb.019281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tandler B, Riva L, Loy F, Conti G, Isola R. High resolution scanning electron microscopy of the intracellular surface of intercalated disks in human heart. Tissue Cell. 2006;38:417–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tice.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tota B. Functional cardiac morphology and biochemistry in Atlantic bluefin tuna. In: Sharp G, Dizon A, editors. The Physiological Ecology of Tunas. New York: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- Tota B. Vascular and metabolic zonation in the ventricular myocardium of mammals and fishes. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1983;76:423–437. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(83)90442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volk T, Geiger B. A 135-kd membrane protein of intercellular adherens junctions. EMBO J. 1984;3:2249–2260. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb02123.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vornanen M. L-type Ca2+ current in fish cardiac myocytes: effects of thermal acclimation and beta-adrenergic stimulation. J Exp Biol. 1998;201:533–547. doi: 10.1242/jeb.201.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vornanen M, Shiels HA, Farrell AP. Plasticity of excitation–contraction coupling in fish cardiac myocytes. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2002;132:827–846. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschke J. The desmosome and pemphigus. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:21–54. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0420-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winer N, Lefevre M, Nomballais MF, et al. Persisting spongy myocardium. A case indicating the difficulty of antenatal diagnosis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 1998;13:227–232. doi: 10.1159/000020843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]