Abstract

The effect of breastfeeding on cognitive abilities is examined in the offspring of highly educated women and compared to the effects in women with low or middle educational attainment. All offspring consisted of 12-year old mono- or dizygotic twins and this made it possible to study the effect of breastfeeding on mean cognition scores as well as the moderating effects of breastfeeding on the heritability of variation in cognition. Information on breastfeeding and cognitive ability was available for 6,569 children. Breastfeeding status was prospectively assessed in the first years after birth of the children. Maternal education is positively associated with performance on a standardized test for cognitive ability in offspring. A significant effect of breastfeeding on cognition was also observed. The effect was similar for offspring with mothers with a high, middle, and low educational level. Breast-fed children of highly educated mothers score on average 7.6 point higher on a standardized test of cognitive abilities (CITO test; range 500–550; effects size = .936) than formula-fed children of mothers with a low education. Individual differences in cognition scores are largely accounted for by additive genetic factors (80%) and breastfeeding does not modify the effect of genetic factors in any of the three strata of maternal education. Heritability was slightly lower in children with a mother with a middle-level education.

Keywords: Breastfeeding, Cognition, Maternal education, G×E

Introduction

Parents with a high IQ, who score high on a range of cognitive abilities, tend to have children with above average IQ scores. This familial clustering of high IQ might be due to genetic inheritance or might be caused by environmental factors. Research on the causes of individual differences in cognitive functioning has established that the heritability of normal cognitive functioning increases over age, with a broad range heritability estimates varying from 25% in children to 85% in adults (e.g., Haworth et al. 2009; Bartels et al. 2002a; Bouchard and McGue 1981). In young children, the familial clustering of IQ is not lower than in adults, but the reasons for clustering lie more in the influence of shared family environment than in the influence of shared genes. Parents of high and low IQ differ across a range of “environmental” characteristics. One environmental factor possibly of importance for cognition is breastfeeding.

The beneficial effects of breastfeeding are reflected in a 2–5 point increase in IQ favoring breast-fed over formula-fed infants (see for example Kramer et al. 2008; Evenhouse and Reilly 2005; Mortensen et al. 2002; Angelsen et al. 2001; Anderson et al. 1999; Jacobson et al. 1999). The biological basis for the beneficial effects of breastfeeding is hypothesized to be based on nutritional processes involving long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LCPUFAs), especially docosahexaonic acid (DHA) and arachidonic acid (ARA) (Marangoni et al. 2000; Koletzko et al. 2008). Compared to formula-fed infants, breast-fed infants had greater proportions of DHA in their red blood cells and brain cortex (Makrides et al. 1994). However, several studies questioned the nutritional benefits of human breast milk on childhood cognitive abilities and indeed found no evidence after adjustment for social and familial characteristics, such as socioeconomic status and parental education (Pollock 1989; Silva et al. 1978; Malloy and Berendes 1998; Wigg et al. 1998). Recently, Der et al. (2006) concluded that breastfeeding has little or no effect on intelligence. They first conducted a prospective analysis revealing that one standard deviation advantage in mother’s IQ more than doubled the odds of breastfeeding and that the effect of breast feeding on cognition disappeared after correction for maternal IQ. They subsequently applied a powerful discordant sib-pair analysis and reported no differences in intelligence between breast-fed and formula-fed individuals of the discordant pairs. Finally, based on the meta-analysis they again conclude that there is effectively no advantage to breast feeding concerning childhood IQ.

So far, most studies of cognition have considered independent effects of genetic and environmental factors. Developments in the field of behavior genetics include studies into gene and environment interaction. Genotype-environment interaction (G×E) refers to the genetic control of sensitivity or susceptibility to differences in the environment (Eaves 1984; Mather and Jinks 1977; Falconer and Mackay 1996; Boomsma and Martin 2002). Knowledge on the biological pathway of the beneficial effects of fatty acids in the brain led to the first G×E study with the finding of a genetic variant in FADS2, a gene involved in the fatty acid pathways, which moderated the association between breastfeeding and cognitive abilities (Caspi et al. 2007). Several G×E studies report that heritability estimates of cognitive ability may be moderated by environmental effects obviously shared by members of the same family, such as parental educational level (Rowe et al. 1999; van der Sluis et al. 2008), race (Turkheimer et al. 2003), social economic status (SES, Turkheimer et al. 2003), and parental income (Harden et al. 2007).

Studies of interactive effects of genes and environment, including breastfeeding, on cognitive abilities are scarce, compared to the wealth of studies on main effects. Studies into the question whether interaction effects might contribute in a similar manner to variation of cognition at the high and low end of the cognitive distribution do not exist. We propose to study the genetic architecture of cognitive functioning in children of high, middle and low educated mothers and examined the main and interactive effects of breastfeeding. We compared the genetic architecture of cognitive ability at age 12 and the possible moderation of breastfeeding in children from high educated mothers, with children with moderate to low educated mothers.

We aim to answer the following questions:

Is there a main effect of breastfeeding on cognitive ability and is this effect different in offspring from highly educated mothers?

Is there a moderation effect of breastfeeding on the genetic architecture of cognitive abilities in offspring of highly educated mothers?

Do these effects differ from the effects in offspring of mothers with a middle or low education?

Methods

Subjects

The total sample for the current study consisted of 4,100 families with 672 monozygotic male twin pairs (MZM), 637 dizygotic male twin pairs (DZM), 860 monozygotic female twin pairs (MZF), 647 dizygotic female twin pairs (DZF), 679 male-female twin pairs (DOSMF), and 598 female–male twin pairs (DOSFM). All families are registered with the Netherlands Twin Register (NTR; Boomsma et al. 2006; Bartels et al. 2007) shortly after the birth of the twins. Data on cognitive abilities were available for 3,132 complete twin pairs and for an extra 149 first born twins and 156 second born twins. Information on breastfeeding status was available for 3,728 twin pairs, with 3,659 twin pairs being concordant (2,140 concordant ‘no’ and 1,519 concordant ‘yes’) and 69 twin pairs discordant for breastfeeding. Maternal educational level was available for mothers of twins. Zygosity was determined by DNA or blood group polymorphisms for 32.6% of the same-sex twin pairs. For the remaining same-sex pairs zygosity was determined by discriminant analysis of questionnaire items. The questionnaire items allowed accurate determination of zygosity of 93% (Rietveld et al. 2000). Zygosity information was lacking for seven families, which were not included in the genetic analyses.

Measures

Cognitive abilities in the twins were assessed with the Dutch CITO-elementary test (Eindtoets Basisonderwijs 2002). The CITO consists of 240 multiple-choice items assessing four different intellectual skills: Language, Mathematics, Information Processing, and World Orientation. Together the performance scales result in a standardized score between 501 and 550. The test is usually administered on three consecutive days in January or February when the children are in the final class of elementary school. The CITO data were collected by mail from teachers after informed consent was obtained from the parents, from the parents at age 12 of the twins, and/or by self report of the twins at age 14 years or older. There was a substantial agreement among the scores from different sources (correlations in the range of .93–.99). The CITO score are moderately to highly correlated to IQ. The correlations were .41, .50, .60, and .63 between CITO and IQ assessed at age 5, 7, 10, and 12 respectively, and this overlap is mainly accounted for by genetic factors (Bartels et al. 2002b).

Breastfeeding was assessed in a questionnaire send to mothers 2 years after the twins were born. Mothers were asked about breastfeeding separately for the oldest and the youngest twin. There were six answer categories; no, less than 2 weeks, 2–6 weeks, 6 weeks to 3 months, 3–6 months, and more then 6 months. A dichotomies variable was created in which ‘no’ and ‘less than 2 weeks’ were categorized as ‘0’ and the remaining categories as ‘1’.

Maternal educational level was assessed when the twins were 3, 7, and 10 years. Educational level was measured on a 13-point scale, ranging from primary education to postdoctoral education the original variable was recoded into three levels (low, middle and high). Educational levels, assessed when the twins were 3 years (preferred since this is closest to the breastfeeding period) were available in 86% of the families. When this time point was missing information assessed at age 7 (in 11.5% of the families) or 10 (in 2.5% of the families) was used. About 85% of the mothers report a stable level of educational level over the 7 year period between the survey at age 3 and the survey at age 10.

Analyses

Genetic structural equation modeling in Mx (Neale et al. 2006) was used with the raw-data Maximum Likelihood procedure for estimation of parameters. Nested submodels were compared by hierarchic χ2 tests. The χ2 statistic is computed by subtracting −2LL (log-likelihood) for the full model from that for a reduced model (χ2 = −2LL1 − (−2LL0)). Given that the reduced model is correct, this statistic is χ2 distributed with degrees of freedom (df) equal to the difference in the number of parameters estimated in the two models (Δdf = df 1 − df 0).

Differences in mean levels of cognitive functioning between the oldest and the youngest of a twin pair, MZ and DZ twins, males and females and sex-differences in variances and covariances were tested for the entire sample. Descriptive statistics were estimated after stratification for educational level of the mother and a test of whether mean levels of cognitive functioning and variances were different in the low, middle, and high maternal educational groups was conducted. Twin correlations for cognitive abilities were estimated conditional on educational level of the mother.

Genetic moderator analyses

Genetic model fitting of twin data allows for separation of the phenotypic variance into its genetic and environmental components. Additive genetic variance (A) is the variance that results from the additive effects of alleles at each contributing genetic locus. Shared environmental variance (C) is the variance that results from environmental events common to both members of a twin pair. Unique environmental variance (E) is the variance that results from environmental effects that are not shared by members of a twin pair. Estimates of the unique environmental effects also include measurement error. To account for this source of variance, E is always specified in the model.

In order to test for the effect of breastfeeding on the genetic architecture of cognitive abilities a moderator model (Purcell 2002) was used. The influence of A (additive genetic influences), C (shared environmental influences) and E (nonshared environmental influences) are represented by paths a + β x M, c + β y M, and e + β z M. M represents the breast-fed status (coded 0 for ‘no’, 1 for ‘yes’). The value of M changes from subject to subject, taking on the value of the measured breastfeeding variable for that subject. If the β is significantly different from zero, there is evidence for a moderating effect on the variance components. In other words, the moderation model allows a test whether the importance of additive genetic effects (a), shared environmental effects (c), and unique environmental effects (e) are changing as a linear function of breastfeeding status. The pathway μ + β m M models the main effect of the moderator variables on the outcome, i.e., the effect of breastfeeding on mean levels of cognitive functioning. The inclusion of the moderator in the mean model adjusts for possible effects of gene-environment correlation.

Model fitting started with a full model (ACE) with moderation on all components and moderation on the means for all three groups of educational level. Significance of the C component and its moderation was tested for first. Next, a test of whether the moderator effect on A and E were similar over the three groups of maternal education was carried out. If the moderating effect of breastfeeding is not the same across the educational strata and interaction between breastfeeding and maternal education is suggested. Next, significance of the moderators on A and E was tested by constraining them at zero. Effects on the mean were tested to be equal over the three strata of maternal education. Standardized estimates for genetic and environmental influences, and their 95% confidence interval, on cognitive ability in the subgroups were estimated.

Results

The percentage of offspring who were breast-fed increased as a function of maternal educational level. Within the group of highly educated mothers 60% of the offspring were breast-fed in comparison to 42 and 30% in mothers with a middle or low education. Means and variance of cognitive ability are presented in Table 1. There was no effect of birth order (P = .73) and zygosity (P = .63) on the means, indicating that first and second born twins score on average similar on the CITO and that there was no difference in mean score for MZ versus DZ twins. A significant effect of sex on mean levels of cognitive abilities was found (P = .03). Boys (mean = 537.94) score on average higher than girls (mean = 536.99). To account for this effect sex was included as a covariate (definition variable coded as 0 for boys and 1 for girls) in the remaining analyses. Variances and covariance were equal for boys and girls (P = .15), so subsequent model fitting is carried out for MZ and DZ groups. Mean levels of cognitive abilities (Table 1) differ significantly for the three maternal educational groups (P = .00 for the three and all two by two comparisons). The sex effect on the mean was similar (β = −.88; P = .98), and significant in all three groups. Variances in cognitive abilities differed for the three maternal educational groups. The variance was larger in the low education group and decreased from the middle to the high group (see Table 1). This represents a ceiling effect in our measure of cognitive abilities, resulting in a decrease in variance in offspring of highly educated mothers. Variance differences between the different strata of education, however, were left intact in our analyses.

Table 1.

Means and variances of cognitive ability for the entire sample and the three educational subgroups

| Mean | Variance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entire sample (n = 6,569) | All | 537.54 | 75.80 |

| ♂ | 537.94 | ||

| ♀ | 536.99 | ||

| Low education (n = 2,324) | All | 534.70 | 83.04 |

| ♂ | 535.03 | ||

| ♀ | 534.15 | ||

| Middle education (n = 2,754) | All | 537.75 | 66.94 |

| ♂ | 538.26 | ||

| ♀ | 537.38 | ||

| High education (n = 1,419) | All | 541.57 | 50.54 |

| ♂ | 541.83 | ||

| ♀ | 540.95 | ||

Twin correlations are summarized in Table 2. In all three subgroups MZ correlations were about twice the DZ correlations pointing to additive genetic effect as the main source of individual differences in cognition. Furthermore, no obvious differences in MZ and DZ correlations were found for the different levels of maternal educational level.

Table 2.

Twin correlations for cognitive ability, with their 95% confidence interval, for the entire sample and the three maternal educational subgroups

| MZ | DZ | |

|---|---|---|

| Entire sample |

.83 (.81–.84) n = 1,192 pairs |

.45 (.41–.48) n = 1,938 pairs |

| Low education |

.84 (.81–.86) n = 404 pairs |

.40 (.34–.47) n = 690 pairs |

| Middle education |

.78 (.75–.81) n = 506 pairs |

.37 (.31–.43) n = 809 pairs |

| High education |

.82 (.79–.85) n = 282 pairs |

.39 (.31–.47) n = 439 pairs |

Moderator models

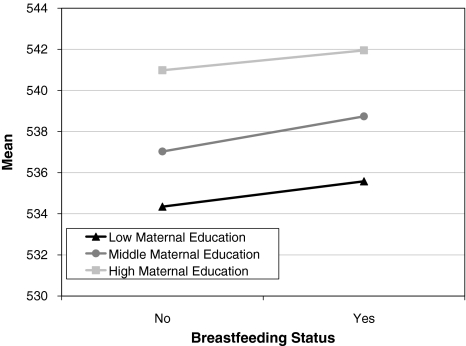

Table 3 presents the model fitting results for the analyses in which data from the three maternal educational strata are analyzed simultaneously. Shared environment and its moderator are not significant (models 1a–c and 2a–c; all P > .05). Constraining the additive genetic moderator to be equal in the three educational groups resulted in a non significant deterioration of fit (model 3a; P = .89). Nonshared environmental moderation was also not different for the different educational groups (model 3b; P = .34). Both the additive genetic and the nonshared environmental moderators could be dropped from the model (model 4a and 4b; P > .05). Mean moderation is significant (β = 1.42; model 5b; P = .00) and similar for all three groups (model 5a; P = .55). This indicated that there is a significant main effect of breastfeeding on cognitive ability. The effect of breastfeeding is significant over and above the significant differences in mean levels of cognitive ability due to the educational level of the mother (see Fig. 1). For individuals in all three strata of maternal education differences in CITO score are mainly accounted for by additive genetic effects (see Table 4). The 95% confidence interval difference for additive genetic effects between the low and middle educational group indicates small but significant differences in heritability of cognition. Overall, 78–84% of the variance in CITO is explained by additive genetic effects and the remaining variance is accounted for by nonshared environmental effects.

Table 3.

Genetic model fitting results for the parallel analyses of the three groups based on maternal educational level

| Model | −2LL | df | ctm | χ2 | df dif | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ACE model with ACE moderation | 44707.77 | 6,544 | ||||

| 1a. drop CLOW | 44707.77 | 6,545 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1b. drop CMIDDLE | 44707.77 | 6,545 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1c. drop CHIGH | 44707.78 | 6,545 | 1 | .01 | 1 | .92 |

| 2. AE model with ACE moderation | 44707.77 | 6,547 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 2a. drop CLOW moderation | 44707.77 | 6,548 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2b. drop CMIDDLE moderation | 44707.77 | 6,548 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 2c. drop CHIGH moderation | 44707.77 | 6,548 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 3. AE model with AE moderation | 44707.77 | 6,550 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| 3a. Equate A moderation over strata | 44708.00 | 6,552 | 3 | .23 | 2 | .89 |

| 3b. Equate E moderation over strata | 44709.92 | 6,552 | 3 | 2.15 | 2 | .34 |

| 4. Equate A & E moderation over strata | 44711.24 | 6,554 | 3 | 3.47 | 4 | .48 |

| 4a. drop A moderation | 44714.05 | 6,555 | 4 | 2.81 | 1 | .09 |

| 4b. drop E moderation | 44713.42 | 6,555 | 4 | 2.18 | 1 | .14 |

| 5. AE model without moderation | 44719.26 | 6,556 | 4 | 8.02 | 2 | .02 |

| 3 | 11.49 | 6 | .07 | |||

| 5a. Equate mean moderation over strata | 44720.46 | 6,558 | 5 | 1.2 | 2 | .55 |

| 5b. Drop the mean moderation | 44752.16 | 6,559 | 5a | 31.7 | 1 | .00 |

| 5. Best model | 44720.46 | 6,558 | 1 | 12.69 | 14 | .55 |

ctm compared to model

Fig. 1.

Observed mean levels of cognitive abilities for breast-fed versus formula-fed 12-year-olds stratified by maternal educational level

Table 4.

Standardized estimates (95% CI) of additive genetic and nonshared environmental effect on cognitive abilities

| A | E | |

|---|---|---|

| Low education | .84 (.81–.86) | .16 (.14–.19) |

| Middle education | .78 (.75–.81) | .22 (.19–.25) |

| High education | .82 (.79–.85) | .18 (.15–.22) |

Discussion

The current study investigated differences in genetic architecture and mean levels of cognitive abilities in children of highly educated mothers versus children of low and middle educated mother, testing for the possible effect of breastfeeding on both the etiology and the mean levels of cognition.

In line with previous studies we found a main effect of breastfeeding status on cognitive abilities after controlling for educational level of the mother. The effect of breastfeeding is similar in the three educational strata. Combining the main effect of educational level of the mother and the main effects of breastfeeding reveals that breast-fed children of highly educated mothers score on average 7.6 point higher on the CITO test of cognitive abilities than formula-fed children of mothers with a low education (effect size = .936). Given that highly educated mothers far more often breast feed their offspring one can speak of a double advantage model. A ‘double advantage’ phenomenon in the context of cognitive ability and education has been proposed earlier by Jencks et al. (1972). He postulated that individuals who begin life with the advantage of genes which increase their ability relative to the average may also be born into homes that provide them with more enriched environments, for instance being more committed to learning and teaching. In line with the current study the more enriched environment can be specified as being breast-fed.

Breastfeeding status had no influence on the genetic architecture of cognition in 12-year-olds. Comparison of the causes of individual differences in CITO scores between children of highly educated mother versus offspring of moderate to low educated mothers revealed only a small but significant difference between the magnitudes of additive genetic influences of the low versus the middle educated group. In offspring of low educated mothers 84% of the variance in cognitive abilities is accounted for by genetic effects, while this variance component is estimated at 78% in offspring of middle educated mother.

A limitation of the current study is the observed ceiling effect in our measure of cognitive abilities, resulting in a decrease in variance in offspring of highly educated mothers. Variance differences between the different strata of education, however, were left intact in our analyses. The fact that we recoded the breastfeeding variable from a six category variable into a dichotomous variable might also be seen as a limitation. However, analyses of variance within the sample of breastfed children (excluding the complete formula fed children and <2 weeks breastfed children from of the analyses), showed no dose-response effect for children of low and high educated mothers. For the middle educated group the only effect that is found is between more or less than 6 weeks of breastfeeding (P < .05). A third limitation is that maternal educational level instead of a direct measure of cognition, such as maternal IQ is used. Although it is to be expected that high IQ mothers cluster in the high educated group and low IQ mothers in the low educated group, this was not investigated for the entire sample, since only very limited information on maternal IQ is currently available at the NTR. In the small available sample (n = 107 mothers) the expected pattern of mean sum IQ scores on the Raven Progressive Matrices (Raven et al. 1998) is observed with the high educational group showing significant higher mean IQ (27.82) than the middle education group (22.79) and low education group (17.56), respectively (P = .002). Der et al. (2006) reported that the effect of maternal education was weaker than the effect of maternal IQ, but that maternal education made an independent contribution, besides the strong effect of maternal IQ.

Overall our study provided no evidence for a moderation of the genetic architecture of cognition by breastfeeding and maternal education. We, however, report a significant positive effect of breastfeeding on cognitive abilities over and above the expected positive effect of maternal education.

Acknowledgments

Data collection was funded by the following grants “Genetics of externalizing disorders in children” (NWO 904-57-94), “Spinozapremie” (NWO/SPI 56-464-14192); “Twin-family database for behavior genetics and genomics studies” (NWO 480-04-004). “Twin research focusing on behavior and depression” (NWO 400-05-717); “Developmental Study of Attention Problems in Young Twins” (NIMH, RO1 MH58799-03) and “Bridge Award” (NIMH R56).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

Edited by Stacey Cherny.

References

- Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Remley DT. Breast-feeding and cognitive development: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;70(4):525–535. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/70.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelsen NK, Vik T, Jacobsen G, Bakketeig LS. Breast feeding and cognitive development at age 1 and 5 years. Arch Dis Child. 2001;85(3):183–188. doi: 10.1136/adc.85.3.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M, Rietveld MJH, van Baal GCM, Boomsma DI. Genetic and environmental influences on the development of intelligence. Behav Genet. 2002;32(4):237–249. doi: 10.1023/A:1019772628912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M, Rietveld MJH, van Baal GCM, Boomsma DI. Heritability of Educational Achievement in 12-year-olds and the overlap with cognitive ability. Twin Res. 2002;5(6):544–553. doi: 10.1375/136905202762342017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels M, Van Beijsterveldt CEM, Derks EM, Stroet TM, Polderman JC, Hudziak JJ, et al. Young Netherlands Twin Register (Y-NTR): a longitudinal multiple informant study of problem behavior. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2007;10:3–11. doi: 10.1375/twin.10.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, Martin NG. Gene-environment interactions. In: D’haenen HD, den Boer JA, Willner P, editors. Biological psychiatry. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boomsma DI, de Geus EJC, Vink JM, Stubbe JH, Distel MA, Hottenga JJ, et al. Netherlands Twin Register: from twins to twin families. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2006;9:849–857. doi: 10.1375/twin.9.6.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard TJ, Jr, McGue M. Familial studies of intelligence: a review. Science. 1981;212:1055–1059. doi: 10.1126/science.7195071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Williams B, Kim-Cohen J, Craig IW, Milne BJ, Poulton R, Schalkwyk LC, Taylor A, Werts H, Moffitt TE. Moderation of breastfeeding effects on the IQ by genetic variation in fatty acid metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(47):18860–18865. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704292104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Der G, Batty GD, Deary IJ. Effect of breast feeding on intelligence in children: prospective study, sibling pairs analysis, and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2006;333(7575):945. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38978.699583.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LJ. The resolution of genotype × environment interaction in segregation analysis of nuclear families. Genet Epi. 1984;1(3):215–228. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370010302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eindtoets Basisonderwijs (2002) CITO. Citogroep, Arnhem

- Evenhouse E, Reilly S. Improved estimates of the benefits of breastfeeding using sibling comparisons to reduce selection bias. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1781–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS, Mackay TFC. Introduction to quantitative genetics. Essex: Longman Scientific and Technical; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Turkheimer E, Loehlin JC. Genotype by environment interaction in adolescents’ cognitive aptitude. Behav Genet. 2007;37:273–283. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9113-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth CMA, Wright MJ, Luciano M, Martin NG, de Geus EJC, van Beijsterveldt CEM, Bartels M, Posthuma D, Boomsma DI, Davis OSP, Kovas Y, Corley RP, DeFries JC, Hewitt JK, Olson RK, ARhea SA, Wadsworth J, Iacono WG, McGue M, Thompson LA, Hart A, Petrill SA, Lubinski D, Plomin R (2009) The heritability of general cognitive ability increases linearly from childhood to young adulthood. Mol Psychiatry. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jacobson SW, Chiodo LM, Jacobson JL. Breastfeeding effects on intelligence quotient in 4- and 11-year-old children. Pediatrics. 1999;103(5):e71. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.5.e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Smith M, Acland K, Bane MJ, Cohen D, Gintis H, Heyns B, Michelson S. Inequality: a reassessment of the effects of family and schooling in America. New York: Basic Books; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Koletzko B, Lien E, Agostoni C, Böhles H, Campoy C, Cetin I, Decsi T, Dudenhausen JW, Dupont C, Forsyth S, Hoesli I, Holzgreve W, Lapillonne A, Putet G, Secher NJ, Symonds M, Szajewska H, Willatts P, Uauy R, World Association of Perinatal Medicine Dietary Guidelines Working Group The roles of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in pregnancy, lactation and infancy: review of current knowledge and consensus recommendations. J Perinat Med. 2008;36(1):5–14. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MS, Aboud F, Mironova E, Vanilovich I, Platt RW, Matush L, Igumnov S, Fombonne E, Bogdanovich N, Ducruet T, Collet JP, Chalmers B, Hodnett E, Davidovsky S, Skugarevsky O, Trofimovich O, Kozlova L, Shapiro S, Promotion of Breastfeeding Intervention Trial (PROBIT) Study Group Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: new evidence from a large randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):578–584. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makrides M, Neumann MA, Byard RW, Simmer K, Gibson RA. Fatty acid composition of brain, retina, and erythrocytes in breast- and formula-fed infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60(2):189–194. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malloy MH, Berendes H. Does breast-feeding influence intelligence quotients at 9 and 10 years of age? Early Hum Dev. 1998;50(2):209–217. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3732(97)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marangoni F, Agostoni C, Lammardo AM, Giovannini M, Galli C, Riva E. Polyunsaturated fatty acid concentrations in human hindmilk are stable throughout 12-months of lactation and provide a sustained intake to the infant during exclusive breastfeeding: an Italian study. Br J Nutr. 2000;84(1):103–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather K, Jinks JL. Introduction to biometrical genetics. London: Chapman and Hall; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen EL, Michaelsen KF, Sanders SA, Reinisch JM. The association between duration of breastfeeding and adult intelligence. JAMA. 2002;287(18):2365–2371. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MC, Boker SM, Xie G, Maes HH. Mx: statistical modeling. 7. Richmond: VCU, Department of Psychiatry; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pollock JI. Mother’s choice to provide breast milk and developmental outcome. Arch Dis Child. 1989;64(5):763–764. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.5.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S. Variance components models for gene-environment interaction in twin analysis. Twin Res. 2002;5(6):554–571. doi: 10.1375/136905202762342026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J, Raven JC, Court JH. Raven manual: section 4 advanced progressive matrices. Oxford: Oxford Psychologists Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld MJH, van der Valk JC, Bongers IL, Stroet TM, Slagboom PE, Boomsma DI. Zygosity diagnosis in young twins by parental report. Twin Res. 2000;3:134–141. doi: 10.1375/136905200320565409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Jacobson KC, van den Oord EJCG. Genetic and environmental influences on vocabulary IQ: parental education level as moderator. Child Dev. 1999;70(5):1151–1162. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva PA, Buckfield P, Spears GF. Some maternal and child developmental characteristics associated with breast feeding: a report from the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Child Development Study. Aust Paediatr. 1978;J14(4):265–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1978.tb02996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turkheimer E, Haley A, Waldron M, D’Onofrio B, Gottesman II. Socioeconomic tatus modifies heritability of IQ in young children. Psychol Sci. 2003;14(6):623–628. doi: 10.1046/j.0956-7976.2003.psci_1475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Sluis S, Willemsen G, de Geus EJC, Boomsma DI, Posthuma D. Gene-environment interaction in adults’ IQ scores: measures of past and present environment. Behav Genet. 2008;38:348–360. doi: 10.1007/s10519-008-9212-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigg NR, Tong S, McMichael AJ, Baghurst PA, Vimpani G, Roberts R. Does breastfeeding at six months predict cognitive development? Aust N Z J Public Health. 1998;22(2):232–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842X.1998.tb01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]