Abstract

Kinesin-3 motor UNC-104/KIF1A is essential for transporting synaptic precursors to synapses. Although the mechanism of cargo binding is well understood, little is known how motor activity is regulated. We mapped functional interaction domains between SYD-2 and UNC-104 by using yeast 2-hybrid and pull-down assays and by using FRET/fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy to image the binding of SYD-2 to UNC-104 in living Caenorhabditis elegans. We found that UNC-104 forms SYD-2-dependent axonal clusters (appearing during the transition from L2 to L3 larval stages), which behave in FRAP experiments as dynamic aggregates. High-resolution microscopy reveals that these clusters contain UNC-104 and synaptic precursors (synaptobrevin-1). Analysis of motor motility indicates bi-directional movement of UNC-104, whereas in syd-2 mutants, loss of SYD-2 binding reduces net anterograde movement and velocity (similar after deleting UNC-104's liprin-binding domain), switching to retrograde transport characteristics when no role of SYD-2 on dynein and conventional kinesin UNC-116 motility was found. These data present a kinesin scaffolding protein that controls both motor clustering along axons and motor motility, resulting in reduced cargo transport efficiency upon loss of interaction.

Keywords: motor regulation, synaptic vesicle transport, active zone protein, axonal transport, dynein

The neuron is a highly polarized cell that possesses dendrites that are specialized for signal reception, and an axon for conduction and transmission. In axonal presynaptic termini, proper vesicle pool organization at the “active zone” and recruitment of synaptic vesicles apposing postsynaptic receptors is completed by complex interactions of presynaptic proteins, including SYD-2/liprin-α. The syd-2 gene encodes a member of the liprin family of proteins (i.e., “LAR-interacting proteins”) that assembles into protein scaffolds that localize presynaptic proteins and mediates targeting the presynaptic transmission machinery to opposite postsynaptic densities (1). It was reported that defects in the syd-2 gene cause a diffuse localization of synaptic vesicle markers in conjunction with a lengthening of presynaptic active zones in Caenorhabditis elegans GABAergic DD and VD motoneurons (2) whereas a mutation in the coiled-coil domain promotes synapse formation dependent on ELKS (3). SYD-2 seems to play a key role in recruiting presynaptic components acting downstream of the synaptic guidepost protein SYG-1 (4). In addition to a scaffolding function at the synapse, Drosophila liprin-α mutants display synaptic vesicle transport defects (5).

The long-range transport of vesicle cargo to synaptic sites requires molecular motor proteins of the kinesin superfamily. UNC-104/KIF1A, a member of the kinesin-3 family, is an essential neuron-specific, monomeric motor that transports synaptic vesicle precursors via a motor/lipid interaction involving the motor's pleckstrin homology (PH) domain (6). Mutations in C. elegans UNC-104 impair the anterograde transport of presynaptic vesicles from the soma to the synapse which results in uncoordinated, slow body movements of the worm (7). Shin et al. (8) reported a direct interaction of liprin-α with KIF1A in vitro, suggesting that liprin-α may function as a KIF1A receptor that links the motor to various liprin-α-associated proteins such as glutamate receptor-interacting protein and AMPA glutamate receptors (9, 10). As the function of KIF1A/liprin-α interaction remains unknown, we evaluated the underlying mechanisms of UNC-104/SYD-2 interaction in vitro and in vivo. As SYD-2 is thought to be a cargo of UNC-104 (11), we hypothesize that the scaffolding protein SYD-2 might coordinate motor organization on the synaptic vesicle membrane, which could regulate anterograde cargo transport (12, 13).

Results

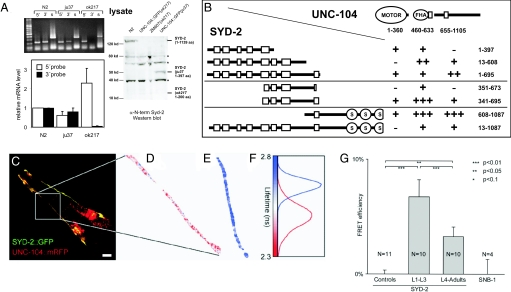

The functional interaction between UNC-104 and SYD-2 was studied in worms expressing UNC-104 fused to the N terminus of a fluorescent protein [GFP or monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP); supporting information (SI) Fig. S1A]. We used 2 syd-2 mutant alleles: a point mutation in glutamine 397 leading to a stop codon in the coiled-coil region (named ju37, ref. 2) and a deletion covering most of the N-terminal coiled-coils (named ok217). Note that the graph in Fig. 1A shows averages of relative mRNA levels [based on real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) experiments] and the gel (Fig. 1A Upper Left) shows a selected single RT-PCR experiment. Thus, band intensities in the gel do not necessarily reflect the average mRNA levels as we have determined by qPCR. Sequencing the ok217 allele revealed a missense mutation leading to an ochre stop codon at position 200. To test for expression of truncated SYD-2 products, we detected full-length proteins in N2 lysates and the corresponding protein fragment in syd-2(ju37) by Western blotting [Fig. 1A; UNC-104::GFP(ju37)]. However, no ok217 fragment (1–200 aa) was detected [lanes UNC-104::GFP(ok217) and ZM607(ok217)]; possibly because of degradation of this small protein trunk in the worm (even though high mRNA levels were detected; Fig. 1A). Thus, the ok217 allele may represent a null allele, whereas ju37 shows detectable levels of both mRNA and truncated protein.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of UNC-104/SYD-2 interactions. In vitro analysis: (A) (Top Left) RT-PCR of 5′ and 3′ regions upstream the ok217 mutation and SAM domain, respectively, in WT (N2) and syd-2 mutants [syd-2(ju37), syd-2(ok217)]. s, synaptobrevin as an internal control. (Bottom left) Real-time qPCR quantification of the 5′ and 3′ probes (Top) using the ribosomal protein rpl-18 gene as an internal control. (Right) Western blot of total worm lysates from N2, UNC-104::GFP(ok217), ZM607(ok217), and UNC-104::GFP(ju37) worms. Polyclonal antibody against the N-terminal region 30 to 80 aa recognizes full-length SYD-2 in WT (125 kDa) and a 47-kDa band in ju37. Asterisks mark non-specific bands that are not reproducible. (B) Yeast 2-hybrid interactions. The interaction strengths are shown in the table with the following groups: constructs representing the SYD-2 coiled-coil regions (Top), constructs containing the last 4 coiled coils with strongest interaction (Middle), and constructs emphasizing the interaction of SYD-2 full-length versus its C-terminal half (Bottom). Strength of interactions is indicated as follows: +++, very strong; ++, strong; +, weak; and -, negative. In vivo analysis: (C) Confocal image of GFP::SYD-2 and UNC-104::mRFP expressed in head neurons. (D and E) False color representation of GFP::SYD-2 lifetimes in the presence (C, D) and absence (E) of UNC-104::mRFP. Corresponding lifetime histograms are shown in F. Worms expressing GFP::SYD-2 alone exhibit a fluorescence lifetime significantly higher than in worms co-expressing UNC-104::mRFP. (G) Animals at larval stages L1 to L3 reveal a FRET efficiency of 6.7% ± 1.5% (n = 10 worms). L4-adult animals exhibit a lower FRET efficiency equal to 3.3% ± 0.8% (n = 10 worms); confidence level P < 1% (Student t test). Worms expressing both SNB-1::GFP and UNC-104::mRFP show no FRET as the fluorophores are on opposite sides of the vesicle membrane. Values represent mean ± SEM. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

Yeast 2-hybrid analysis was performed to test interaction domains of UNC-104 and SYD-2. Based on the known interaction of liprin-α and KIF1A (8), the motor's stalk and liprin's coiled-coil domains are prime candidates for in vitro binding testing. In addition to the previously published interactions, we found that either all (1–695) or some coiled-coils (341–695) of SYD-2 weakly interact with UNC-104 domain constructs (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1). The most prominent interaction occurs with the C-terminal half of SYD-2, including the SAM domains and UNC-104 stalk and FHA domain; still, interestingly, region 1–397 (corresponding to ju37 allele) also interacts with the FHA and stalk domains. However, the interaction of a nearly full-length SYD-2 (13–1,087) with UNC-104 is reduced. Direct binding was confirmed by pull-down experiments with recombinantly expressed proteins (Fig. S1B). Based on these findings, we assume that SYD-2's coiled coils can intramolecularly interact with its SAM domains, thus masking potential UNC-104 binding sites (14). These data suggest that SYD-2 and UNC-104 can interact through multiple domains, while strong interactions occur between the SYD-2's coiled coils 5–8 and SAM domains and UNC-104's FHA and stalk domains, respectively.

In Vivo FRET/Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy Experiments Reveal a Close SYD-2/UNC-104 Interaction.

Fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) measurements were used to determine whether SYD-2 and UNC-104 are able to physically interact in the living worm. Head neurons of the worm expressing both GFP::SYD-2 and UNC-104::mRFP appeared to be useful for imaging and analysis (Fig. 1C), whereas we did not find any differences in FLIM signals comparing the short ring-type axonal trunks and the dendritic extension, thus focusing on the dendrites. Unfortunately, expression of SYD-2 in the sub-lateral nervous system was too low to reveal a stable signal. If interaction occurs between 2 fluorophores in close proximity (<5 nm), the fluorescence lifetime of GFP is expected to decrease as a result of FRET. Worms expressing only GFP::SYD-2 (Fig. 1E) exhibit a fluorescence lifetime of 2.74 ns ± 0.01 (n = 11 worms), typical for GFP in the absence of FRET and significantly higher than in worms expressing both GFP::SYD-2 and UNC-104::mRFP (Fig. 1D; color bar and lifetime histograms in Fig. 1F; also see SI text). As a negative control, worms expressing both SNB-1::GFP and UNC-104::mRFP were analyzed by FRET/FLIM. Although motor and cargo vesicles co-localize under epi-fluorescence observation (Fig. 4G), the 2 respective fluorophores should not be in close proximity as the GFP of the synaptobrevin is located inside the vesicle membrane (15), whereas the mRFP of the UNC-104 is located outside (Fig. 1G). In summary, these results reveal an in vivo interaction of UNC-104 with SYD-2 in the living worm that appears more pronounced in younger animals.

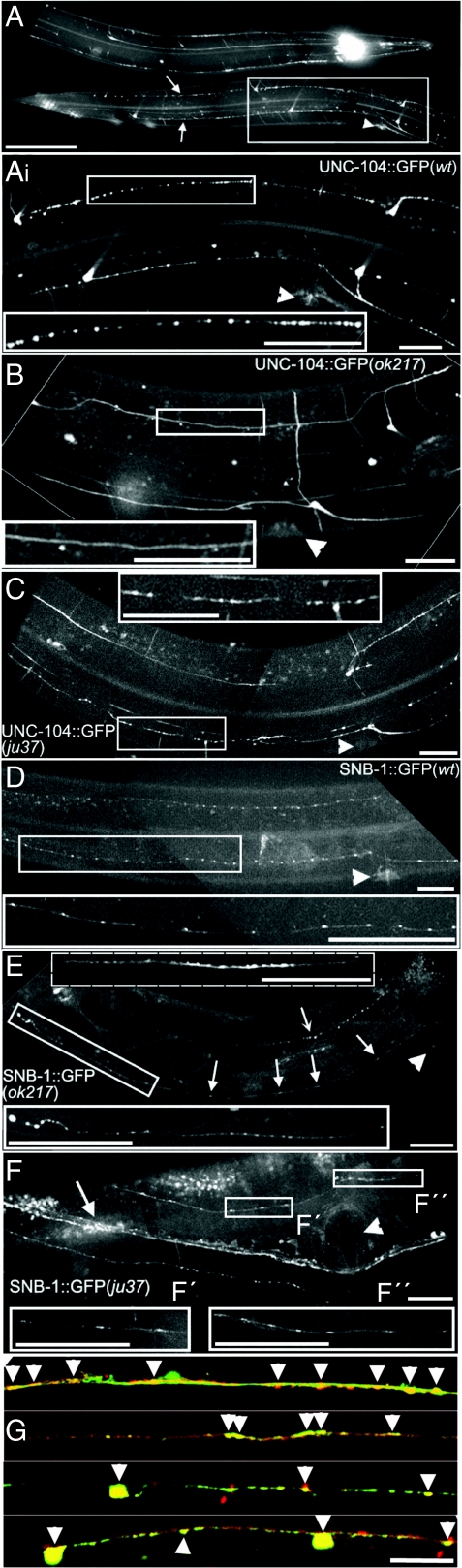

Fig. 4.

Axonal distribution pattern of UNC-104, SNB-1, and SYD-2. (A and Ai) UNC-104::GFP clustering in the ventral and dorsal sub-lateral neurons (arrow). Arrowhead indicates vulva. (Scale bars, 100 μm in A, 25 μm in Ai.) (B) Clustering is significantly reduced in syd-2(ok217) worms and fewer cluster are observed in the ju37 mutant (C). (D) Pearl string-like distribution pattern of synapses (SNB-1::GFP) differs from the distribution pattern of UNC-104 clusters in A. (E) In syd-2(ok217) worms, synapses are arranged more irregularly (Top Inset) compared with the WT worm (D) and tend to accumulate in the terminal endings (Bottom Inset). Dashed inset represents an example of a frequently observed diffuse accumulation of SNB-1. (F) In ju37 worms, synapses appear elongated (arrowhead indicates vulva; F′ and F′′ Inset with dashed line shows another example of SYD-2 distribution). (G) Co-localization of UNC-104::GFP (green) and SNB-1::mRFP (red) in sub-lateral neurons. Arrowheads indicate synapses. (Scale bar, 25 μm in B-G.)

SYD-2 Regulates UNC-104 Motor Motility.

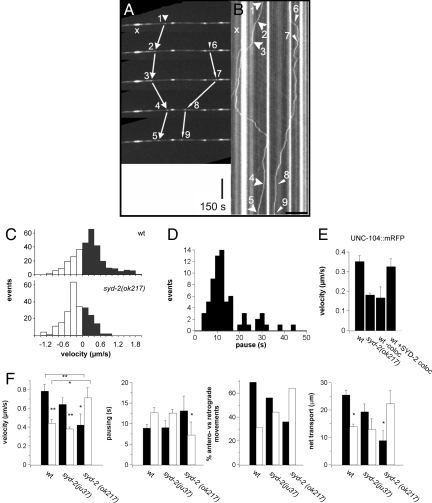

We then compared the transport characteristics of motors and vesicles in WT and syd-2 mutant backgrounds by UNC-104::GFP particle analysis in living worms in sub-lateral neurons (Fig. 2C-F) and in isolated neurons (Fig. 3) by using spinning-disc confocal time-lapse fluorescence microscopy. Two examples of moving particles in a time series is shown in Fig. 2A (Movie S1) with corresponding positions indicated in the kymograph (Fig. 2B; 1-5, 6-9; x, static particle) and active anterograde and retrograde traffic events are shown in Fig. S3B. Most strikingly, in the living worm, anterograde velocity of (bidirectional moving) motor particles is reduced by 20% in UNC-104::GFP[syd-2(ju37)] mutants and by 50% in UNC-104::GFP[syd-2(ok217)] (Fig. 2F), whereas retrograde velocities in UNC-104::GFP[syd-2(ok217)] are significantly higher (twofold increase). The pausing duration (Fig. 2F) is notably increased in the syd-2(ok217) mutant relative to both WT and syd-2(ju37). To test whether the increase in velocity can be directly attributed to the presence of SYD-2, we measured large UNC-104 particle movements (apparent diameter >350 nm) when co-migrating with SYD-2 (Fig. 2E, wt +SYD-2 coloc) or when migrating alone (i.e., without SYD-2 co-localization; Fig. 2E, wt -coloc). In the presence of SYD-2, motor particles moved at similar velocities compared to randomly observed large particles (Fig. 2E, UNC-104) and significantly faster than in syd-2(ok217) background or when not co-localized (see Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

SYD-2 regulates UNC-104 motor activity in living worms. (A) Example of a movie taken from a neuron of a living worm expressing UNC-104::GFP. Five time points are shown revealing 2 moving particles (particle 1, events 1–5; particle 2, events 6–9). As reference, a stationary cluster is marked with an x. The translation of the particle displacement into a kymograph is shown in B. (Scale bars, 150 sec for vertical/time, 10 μm for horizontal/distance.) (C) (Top) Histograms of UNC-104 velocity in anterograde (black bars) and retrograde direction (white bars). (Bottom) For comparison, UNC-104 velocity distribution in syd-2(ok217). (D) Histogram of anterograde pausing durations. (E) Movement of particles >350 nm in diameter show slower velocities than the average particles (in F) with reduced velocities in ok217. In worms co-expressing UNC-104::mRFP/SYD-2::GFP, single UNC-104 particles (wt −coloc) have similar velocities than in ok217, but attain normal velocities when co-migrating with SYD-2 (wt +syd-2 coloc). (F) Velocity, pausing, percentage of directionality, and net transport lengths are presented for UNC-104::GFP in WT, syd-2(ju37), and syd-2(ok217) worms. (Scale bars, 10 sec for vertical/time, 10 μm for horizontal/distance.) Note that anterograde velocity of UNC-104 is reduced in SYD-2 mutants (ju37 and ok217), whereas retrograde velocity is increased in ok217 (F). For detailed discussion, refer to the text and SI text. Values represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (Student t test) comparing anterograde versus retrograde velocity. (Scale bar, 45 μm.)

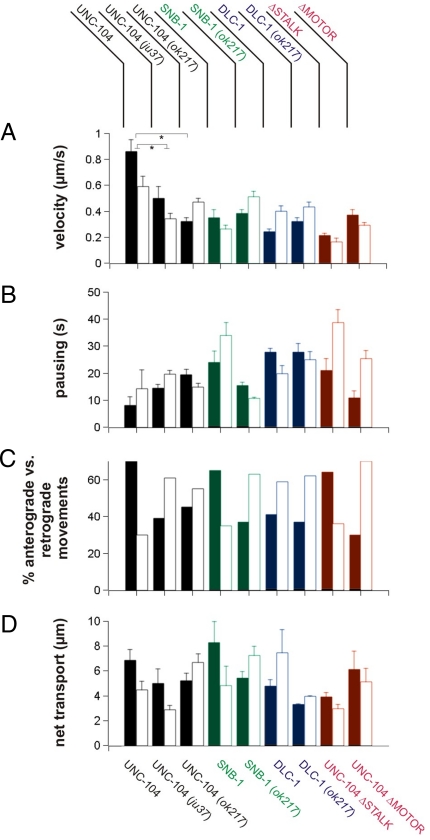

Fig. 3.

Effect of SYD-2 on UNC-104 motility in primary neuronal cell culture. Movement of UNC-104 in WT and syd-2 mutant (ju37, ok217) primary cultured neurons (A-D). Note that UNC-104's properties in cell culture are similar to living worm measurements (Fig. 2). UNC-104 movements in WT and syd-2 mutants are colored in black, synaptobrevin movements in green, dynein movements in blue, and UNC-104 mutant movements in red. DLC-1, dynein-light-chain::YFP, SNB-1, synaptobrevin-1::GFP. Black bars represent anterograde direction; white bars represent retrograde direction. In Figs. 2 and 3, a total of 3,196 events were analyzed. Values represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 (Student t test).

From Fig. 2F it appears that UNC-104 activity is decreased in syd-2 mutants and switches from anterograde-based to retrograde-based movements. Indeed, motor particles exhibited increased net retrograde movements in syd-2 from a predominantly anterograde directionality in WT (Fig. 2F). Similarly, the total net transport (i.e., net displacement over one particle track) is decreased for anterograde events and increased in retrograde directions with a stronger phenotype in syd-2(ok217) (SYD-2 null) than in syd-2(ju37) (C-terminal truncated SYD-2; Fig. 2F).

UNC-104 in cell culture shows the same qualitative switch to retrograde transport parameters and overall velocity reduction in syd-2 mutants (Fig. 3 A-D). Intriguingly, UNC-104's anterograde vesicle-associated cargo SNB-1 undergoes a similar shift to retrograde motility (Fig. 3). As the motor stalk domain interacts with SYD-2 (Fig. 1B), we tested this construct for movement characteristics. UNC-104ΔSTALK shows qualitatively similar changes as observed for UNC-104 in the syd-2(ok217) background with reduced velocity and increased pausing duration (Fig. 3 A and B). However, no difference in the ratio of anterograde/retrograde movement was detected (Fig. 3C) while the total net transport was reduced by 40%. Deletion of the motor head surprisingly showed no dominant negative effect in movement when expressed in N2 WT animals; however, we cannot rule out that motorless UNC-104 does not interact with endogenous motor. As the UNC-104ΔSTALK construct still includes the FHA domain capable of SYD-2 interaction (Fig. 1B), a partial phenotype might explain the anterograde preference. As UNC-104 and vesicles tend to move in syd-2 mutants retrogradely, we chose to evaluate dynein-mediated movements. Expression and analysis of dynein light chain (DLC-1::YFP) shows a directional bias in transport with faster velocity, shorter pausing duration, and increased net transport in retrograde rather than in anterograde direction, with a tendency to overall retrograde events (Fig. 3). DLC-1 movement characteristics were not altered when expressed in ok217 background with the exception of a reduced net transport (Fig. 3). As expected, the vesicle cargo maker SNB-1 undergoes a similar shift to retrograde motility (Fig. 3). Analysis of conventional kinesin (kinesin-I, UNC-116::GFP) velocity, directionality (not shown), and expression pattern shows no difference between WT versus syd-2(ok217) allelic background (Fig. S5).

SYD-2 Scaffolding Protein Clusters UNC-104 in the Ventral and Dorsal Sub-Lateral Neurons.

To test whether, in the living worm, an interaction between SYD-2 and UNC-104 is involved in the axonal localization of UNC-104, we crossed UNC-104::GFP-expressing worms into different syd-2 mutant worms following distribution pattern analysis. Fig. 4 A and Ai shows a representative example of UNC-104 distribution with occasional small punctae and large clusters in the ventral and dorsal sub-lateral neurons. This clustering is significantly reduced in SYD-2-knockout worms (ok217 allele; Fig. 4B), while clustering still occurs (although it is less pronounced) in syd-2(ju37) with shorter truncation products (Fig. 4C). Quantification of cluster properties in neurites reveals a significant decrease in cluster density and an increase in cluster shape elongation in syd-2 mutants (Fig. S2 H and I and Fig. S7G).

To answer the question whether UNC-104::GFP cluster may resemble en passant synapses, we analyzed the distribution pattern of synapses visualized by the synaptic marker synaptobrevin-1, SNB-1::GFP. Fig. 4D shows a more regular (i.e., “pearl string”-like) distribution pattern of synapses compared with UNC-104 particles (Fig. 4A) whereas UNC-104 still co-localizes with SNB-1 in motor clusters (Fig. 4G and Fig. S4). However, in syd-2 mutant sub-lateral nervous system (Fig. 4 E and F Insets), synapses are arranged more irregularly (also see Fig. S7 D, F′, and F″) than in WT, and accumulations can be seen, whereas a diffuse and elongated synaptic morphology is consistent with previous observations from GABAergic DD motor neurons (2). As expected, deletion constructions of UNC-104 lacking SYD-2 interaction domains as STALK and FHA fail to cluster and properly localize in the axon (while deleting the motor and the PH domain did not affect axonal clustering; see Fig. S2). Last, clustering seemed to be dependent on the developmental stages of the worm (Fig. S2 F and G), whereas FRAP experiments (Fig. S6 A and B) and time-lapse imaging (Fig. S6C) reveal that clusters are highly dynamic structures.

Discussion

We wonder why UNC-104 and SYD-2 exhibit multiple interaction domains as revealed by our yeast 2-hybrid assays and used bioinformatics tools to reveal whether SYD-2 would belong to a class of proteins with “intrinsically disordered structures” (16). Examples of intrinsically unstructured proteins (IUPs) include tau/MAP2, SNAP-25, α-synuclein, and neurofilament-H. They have in common a lack of 3D structure in vivo, and their unfolded character enables various functional modes. Proteins of this remarkable class are able to bind to several partners in a structurally adaptive process. We used PrDOS (Protein Disorder prediction system; http://prdos.hgc.jp/cgi-bin/top.cgi) to investigate whether either UNC-104 or SYD-2 would belong to this class of proteins. Interestingly, analysis of UNC-104 did not reveal any relation to the IUP class; however, SYD-2 can be indeed considered an IUP. Thus, we believe that SYD-2's multiple interactions site on UNC-104 would result in its multifarious functioning based on the lack of an ordered structure.

Shin et al. (8) reported that a 455–1,104 amino acid construct of liprin-α binds best to KIF1A at amino acid position 657–1,105 (therefore named the liprin-α binding domain). We confirm these in vitro interactions between similar constructs (UNC-104 655–1,105 and SYD-2 608–1,078; Fig. 1; note that homology between SYD-2 and liprin-α is of 67% similarity and 51% identity; see ref. 2). In addition, we found that a nearly full-length construct of SYD-2 (13–1,087) shows a weaker interaction compared with the shorter 608–1,078 (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1F), possibly based on an intramolecular head-to-tail folding mechanism (17). Most strikingly, the FHA domain of UNC-104 and the C-terminal half of SYD-2 contributes highly to the motor-scaffold interaction (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2). The FHA domain is supposed to be involved in regulating a monomer-to-dimer transition of UNC-104 as a result of its position between the 2 coiled-coil domains (18). In the living worm, UNC-104 and SYD-2 seemed to be adjacent enough for a physical interaction. For discussion on FLIM/FRET experiments and on UNC-104/SYD-2 interaction mechanisms, please refer to the SI text.

UNC-104 and Synaptic Vesicle Motility in Neurons.

Although UNC-104 is thought to move unidirectionally, bidirectional motion of GFP-tagged UNC-104 was observed in vivo (19) (Figs. 2 and 3). Consequently, we discriminated between anterograde and retrograde events. In addition, we differentiated between single event velocities (i.e., no changes of directions) and velocities of runs with several events and directional changes, and found that single event velocities are significantly higher than those with several events. For example, the velocity of UNC-104::GFP(WT) particles with one moving event exhibit an average speed of only 1.12 μm/s ± 0.4 in WT cells [vs. ju37 (0.56 μm/s ± 0.24) or ok217 (0.62 μm/s ± 0.26)], faster than particles with several events and several directional changes (0.81 μm/s ± 0.42 for WT, 0.35 μm/s ± 0.22 for ju37, and 0.43 μm/s ± 0.19 for ok217; see SI text). In Drosophila liprin-α mutants, Miller et al. (5) reported a decrease in the number of synaptobrevin-GFP-tagged vesicles transported in anterograde direction and an increase in the number of those transported in retrograde direction, with unchanged velocity. In addition, vesicles in liprin-α mutants make more stops and sudden reversals. These findings from direct observations in Drosophila are only partially consistent with our findings on SNB-1 motility using C. elegans. Whereas a shift to retrograde events is consistent, we find that the velocity of SNB-1 in the retrograde direction was significantly enhanced in ok217 mutants (Fig. 3A); however, pausing duration (Fig. 3B) was not increased as reported by Miller et al. (5) but, on the contrary, was reduced. Note that differences as shown in Figs. 2 and 3A may occur as a result of different types of syd-2/liprin-α mutations (20).

The speed of SNB-1/VAMP::mRFP transfected in C. elegans primary neuronal cell cultures (highest, 0.68 μm/s; lowest, 0.21 μm/s; average, 0.3 ± 0.13 μm/s; n = 327) was similar to the velocity of SNB-1/VAMP::GFP transfected in hippocampal neurons (up to 0.5 μm/s; compare ref. 21). DLC::YFP or SNB-1::mRFP expression in cells isolated from unc-104 mutants (e1265) did not reveal enough moving events for statistical useful studies. Furthermore, no directional motion was determined for a UNC-104ΔMOTOR::GFP construct transfected in cells isolated from unc-104 mutants (e1265). Thus, the transgene was crossed into a N2 (WT) worm, resulting in mobile UNC-104 with a deleted motor domain that is highly reduced even in the presence of endogenous fully functional motors (Fig. 3A Right). Probably, the truncated motor is still able to associate with endogenous motors, and detected moving characteristics may derive from a mixed motor population (i.e., functional and nonfunctional).

The finding that synaptic vesicles move slower than UNC-104 (SNB-1; Fig. 3A) favors a model wherein multiple motors are attached to a vesicle and are probably involved in a “tug of war.” Evidence for a functional dynein/UNC-104 cargo interaction was reported by Koushika et al. (22), showing that the transport of synaptobrevin, synaptotagmin, and UNC-104 requires the dynein heavy and light intermediate chain, respectively. In cultured neurons, DLC-1 velocity, pausing and directionality are unchanged but with reduced net transport in syd-2 mutants (Fig. 3), suggesting that dynein-based transport is only slightly affected by SYD-2. So far, a direct interaction between SYD-2/liprin-α and dynein could not be proven (5), but an indirect interaction via kinesin-I cannot be excluded. As the velocity of kinesin-I in syd-2 mutants is unchanged compared with WT (Fig. S5C), the rescue of UNC-104 velocity in the presence of SYD-2 (Fig. 2E), together with our in vitro binding studies (Fig. 1 and Fig. S1) suggest that SYD-2 directly enhances anterograde characteristics of UNC-104.

Model for UNC-104/SYD-2 Interaction.

We propose a model in which UNC-104 binding to SYD-2 possibly enhances clustering of UNC-104 on the vesicle surface through multiple interaction domains. When UNC-104 is unbound from its cargo, it might form the largely immobile clusters along the neurite. This might represent a mechanism by which motor can be made locally deposited and available for transport. This interaction could, in turn, increase anterograde motility of the motor and apparently cause randomly distributed motor clusters in the neuron (Fig. S8), which are significantly reduced in ok217 animals. In syd-2 mutants, UNC-104 directionality is impeded while the motor switches to retrograde movements, characteristic for dynein-based motility. Cargo accumulation is a hallmark of several neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS, Alzheimer disease, and Parkinson disease, whereas little is known about how molecular motors are regulated. It is reasonable that other motor adaptor proteins might serve to regulate motility to maintain a balanced state for synaptic cargo delivery.

Materials and Methods

Constructs and C. elegans Strains.

Generation of constructs and worm culturing were carried out according to standard protocols. We provide a thorough description of plasmid construction and the C. elegans strains used in the SI text.

Worm Lysates.

Worm lysates were prepared from mixed-stage worms as described (23). In brief, three 6-cm plates were washed 3 times with M9 buffer and worms were resuspended in 100 mM ethanolamine, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, including protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Diagnostics). Samples were boiled for 80 s and immediately resolved by 4% to 12% SDS/PAGE. Fifty micrograms of total protein lysates was loaded per lane. The polyclonal antibody against the N-terminal region 30 to 80 aa of SYD-2 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

RT-PCR and Real-Time qPCR.

The primers of the 5′ (forward, CAGAACGGAACAATACTCGACTTCT; reverse, TCGCCACACGCTCCATT) end of the syd-2 gene cover a region upstream of the stop codon in the ok217 mutation (600 bp). To evaluate the mRNA expression of the 3′ end, we designed primers upstream of the SAM domains (1,802 bp; forward, CAACCACAAGCTTCGATTGCT; reverse, ACGTCGGCCAGTGATGGT). We took into account that, for RT-PCR experiments, primers need to cover at least one intron. As an internal control we designed primers covering the snb-1 gene. Real-time qPCR experiments were carried out based on the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method (24). We used the ribosomal protein rpl-18 gene as an endogenous control and N2 WT extracts as a “calibrator sample” (for details refer to ref. 24).

Bacterial Protein Expression and Purification.

The fragment 623-1026 of UNC-104 was cloned using standard PCR methods into a pGEX-2T expression vector (Amersham/GE Healthcare). SYD-2 341–695 and 608-1089 fragments were expressed as fusion proteins to maltose binding protein (MBP) in a pMAL-2X expression vector (New England Biolabs). All constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Proteins were expressed and purified by glutathione Sepharose chromatography (Amersham/GE Healthcare) or amylose resin (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer, followed by HiTrap-Q ion exchange chromatography (Amersham/GE Healthcare). Fusion proteins were either assayed or frozen with 10% sucrose added and stored in liquid nitrogen.

Yeast 2-Hybrid Assay.

We used the Matchmaker GAL4 Two-Hybrid System 3 from Clontech (Invitrogen). Please refer to the SI text for detailed description of the yeast 2-hybrid assay analysis.

Primary Neuronal Cell Culture and Transfections.

Primary cell culture was performed according to Christensen et al. (25). Primary neuronal cells with a cell density of approximately 650,000 cells per plate were transfected with either a pPD95.81::Posm-5::DLC-1::YFP or a pSM::Punc-86::SNB-1::mRFP construct by using TransFast transfection reagent (Promega) according to the manufacturer. Transfected cells were incubated at 22 °C in a humidified box for 1 to 2 d before microscopy.

Microscopic Transport Assay.

Imaging was performed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope equipped with a QLC100 spinning disk head and a Roper 512F EMCCD camera (Visitron). For a thorough description of our microscopic transport assay please refer to the SI text.

FRET/FLIM.

Fluorescence lifetime sensing was performed by time-correlated single photon counting. The time-domain FLIM setup used is an upgrade of a TSC-SP2 AOBS laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica), equipped with a mode-locked femtosecond Ti:Sapphire Mira900 laser that is pumped by a Verdi-V8 laser (Coherent). The laser was tuned at 900 nm for 2-photon excitation of EGFP (26). The fluorescence emission of EGFP was detected using a band-pass filter centered at 515 nm ± 15 and placed in front of an MCP-PMT detector (R3809U-50; Hamamatsu Photonics). The acquisition board (SPC830) and software (SPCImage) were both from Becker & Hickl. Further analysis was performed by in-house-developed Matlab routines (MathWorks).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistics of particle movement in the microscopic transport assay were carried out using the Student t test (two-tailed, unequal variance). Mean values are given with ± SEM if not marked otherwise. Statistical significance (confidence level) at a P value <0.05 is noted by asterisks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Ms. Franziska Hartung assisting with yeast 2-hybrid experiments, Ms. Yu-Hsin Huang assisting with yeast 2-hybrid and confocal imaging of UNC-104/SYD-2 co-localization, Dr. Michael Nonet for providing the antibody against SNB-1, Dr. Sandhya Koushika for providing the polyclonal antibody against UNC-104, Dr. Shou-Lin Chang for his IUP analysis using PrDOS, and National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center (Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China) for the use of an Olympus FV1000 for dual-migration analysis of UNC-104/SYD-2. Nematode strains were provided by the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health National Center for Research Resources. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Molecular Physiology of the Brain Research Center (D.R.K.) and by National Science Council of Taiwan Grant 97–2311-B-007–006-MY3 (to O.I.W.). The European Neuroscience Institute Göttingen is jointly funded by the Göttingen University Medical School, the Max-Planck-Society, and Schering.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0902949106/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Olsen O, Moore KA, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Synaptic transmission regulated by a presynaptic MALS/Liprin-alpha protein complex. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:223–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhen M, Jin Y. The liprin protein SYD-2 regulates the differentiation of presynaptic termini in C. elegans. Nature. 1999;401:371–375. doi: 10.1038/43886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dai Y, et al. SYD-2 Liprin-alpha organizes presynaptic active zone formation through ELKS. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1479–1487. doi: 10.1038/nn1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MR, et al. Hierarchical assembly of presynaptic components in defined C. elegans synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1488–1498. doi: 10.1038/nn1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller KE, et al. Direct observation demonstrates that Liprin-alpha is required for trafficking of synaptic vesicles. Curr Biol. 2005;15:684–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klopfenstein DR, Tomishige M, Stuurman N, Vale RD. Role of phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate organization in membrane transport by the Unc104 kinesin motor. Cell. 2002;109:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00708-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall DH, Hedgecock EM. Kinesin-related gene unc-104 is required for axonal transport of synaptic vesicles in C. elegans. Cell. 1991;65:837–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90391-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shin H, et al. Association of the kinesin motor KIF1A with the multimodular protein liprin-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:11393–11401. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Esteban JA. AMPA receptor trafficking: a road map for synaptic plasticity. Mol Interv. 2003;3:375–385. doi: 10.1124/mi.3.7.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schnapp BJ. Trafficking of signaling modules by kinesin motors. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2125–2135. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeh E, Kawano T, Weimer RM, Bessereau JL, Zhen M. Identification of genes involved in synaptogenesis using a fluorescent active zone marker in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3833–3841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4978-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okada Y, Higuchi H, Hirokawa N. Processivity of the single-headed kinesin KIF1A through biased binding to tubulin. Nature. 2003;424:574–577. doi: 10.1038/nature01804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tomishige M, Klopfenstein DR, Vale RD. Conversion of Unc104/KIF1A kinesin into a processive motor after dimerization. Science. 2002;297:2263–2267. doi: 10.1126/science.1073386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serra-Pages C, Medley QG, Tang M, Hart A, Streuli M. Liprins, a family of LAR transmembrane protein-tyrosine phosphatase-interacting proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15611–15620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nonet ML. Visualization of synaptic specializations in live C. elegans with synaptic vesicle protein-GFP fusions. J Neurosci Methods. 1999;89:33–40. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(99)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tompa P. The interplay between structure and function in intrinsically unstructured proteins. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3346–3354. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serra-Pages C, Streuli M, Medley QG. Liprin phosphorylation regulates binding to LAR: evidence for liprin autophosphorylation. Biochemistry. 2005;44:15715–15724. doi: 10.1021/bi051434f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vale RD. The molecular motor toolbox for intracellular transport. Cell. 2003;112:467–480. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00111-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou HM, Brust-Mascher I, Scholey JM. Direct visualization of the movement of the monomeric axonal transport motor UNC-104 along neuronal processes in living Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3749–3755. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-11-03749.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufmann N, DeProto J, Ranjan R, Wan H, Van Vactor D. Drosophila liprin-alpha and the receptor phosphatase Dlar control synapse morphogenesis. Neuron. 2002;34:27–38. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00643-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahmari SE, Buchanan J, Smith SJ. Assembly of presynaptic active zones from cytoplasmic transport packets. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:445–451. doi: 10.1038/74814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koushika SP, et al. Mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans cytoplasmic dynein components reveal specificity of neuronal retrograde cargo. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3907–3916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5039-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Speese S, et al. UNC-31 (CAPS) is required for dense-core vesicle but not synaptic vesicle exocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurosci. 2007;27:6150–6162. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1466-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christensen M, et al. A primary culture system for functional analysis of C. elegans neurons and muscle cells. Neuron. 2002;33:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00591-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Y, Periasamy A. Characterization of two-photon excitation fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy for protein localization. Microsc Res Tech. 2004;63:72–80. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.