Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Although advanced prehospital management (PHM) in ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) reduces reperfusion delay and improves patient outcomes, its use in North America remains uncommon. Understanding perceived barriers to and facilitators of PHM implementation may support the expansion of programs, with associated patient benefit.

OBJECTIVE:

To explore the attitudes and beliefs of paramedics, cardiologists, emergency physicians and nurses regarding these issues.

METHODS:

To maximize the potential to identify unpredictable issues within each of the four groups, focus group sessions were recorded, transcribed and analyzed for themes using the constant comparative method.

RESULTS:

All 18 participants believed that PHM of STEMI decreased time to treatment and improved health outcomes. Despite agreeing that most paramedics were capable of providing PHM, regular maintenance of competence and medical overview were emphasized. Significant variations in perceptions were revealed regarding practical aspects of the PHM process and protocol, as well as ownership and responsibility of the patient. Success and failures of technology were also expressed. Varying arguments against a signed ‘informed consent’ were presented by the majority.

CONCLUSIONS:

Focus group discussions provided key insights into potential barriers to and facilitators of PHM in STEMI. Although all groups were supportive of the concept and its benefits, concerns were expressed and potential barriers identified. This novel body of knowledge will help elucidate future educational programs and protocol development, and identify future challenges to ensure successful PHM of STEMI, thereby reducing reperfusion delay and improving patient outcomes.

Keywords: Acute myocardial infarction, Myocardial infarction, Percutaneous coronary intervention, Reperfusion, Thrombolysis

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Même si la prise en charge préhospitalière avancée (PCP) de l’infarctus du myocarde avec élévation du segment ST (IMEST) réduit le délai de reperfusion et améliore l’issue des patients, on y recourt rarement en Amérique du Nord. Le fait de comprendre les obstacles perçus et les éléments facilitants de l’implantation de la PCP pourrait soutenir l’expansion des programmes et les bienfaits connexes qu’en retirent les patients.

OBJECTIF :

Explorer les aptitudes et les convictions du personnel paramédical, des cardiologues, des médecins d’urgence et des infirmières à l’égard de ces enjeux.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Afin de maximiser le dépistage potentiel des problèmes imprévisibles au sein de chacun des quatre groupes, on a enregistré, transcrit et analysé les séances des groupes de travail afin d’en dégager les thèmes au moyen de la méthode comparative constante.

RÉSULTATS :

Les 18 participants étaient tous d’avis que la PCP de l’IMEST réduisait le délai avant le traitement et améliorait les issues de santé. Même s’ils convenaient que la plupart des membres du personnel paramédical étaient en mesure d’assurer une PCP, ils soulignaient l’importance d’un maintien régulier des compétences et d’un survol médical. On a découvert des variations de perception significatives au sujet des aspects pratiques du processus et du protocole de PCP. Les participants ont également exprimé les réussites et les échecs de la technologie. La majorité ont présenté des arguments variés contre la signature d’un « consentement éclairé ».

CONCLUSIONS :

Les discussions des groupes de travail ont fourni des aperçus clés sur les obstacles potentiels et les éléments facilitants de la PCP de l’IMEST. Même si tous les groupes soutenaient le concept et ses bienfaits, des préoccupations ont été exprimées et des obstacles potentiels déterminés. Ce nouvel ensemble de connaissances contribuera à créer de futurs programmes de formation et protocoles de mise en œuvre ainsi qu’à établir les futurs défis pour assurer une PCP réussie des IMEST, réduisant ainsi le délai de reperfusion et améliorant l’issue des patients.

In 2001, acute myocardial infarction (MI) accounted for 19% of deaths in Canada, and coronary artery disease is the leading cause of death internationally (1). Because timely reperfusion is paramount in salvaging viable myocardial cells and improving clinical outcomes, the American Collegy of Cardiology/American Heart Association and Canadian guidelines emphasize establishing systematic approaches to abate treatment delay (2–6). Advanced prehospital management (PHM), including administration of prehospital fibrinolysis (PHF) on first medical contact in the field, is feasible (7) and has been demonstrated to improve clinical outcomes through reduction in treatment delay (8). Many European health care regions have adopted PHM as a standard of care (9), while North America remains virtually devoid of this treatment approach. This distinction can be explained, in part, by the ability of European health care systems to staff physicians in the prehospital setting, while the health care system in North America depends on paramedics to provide prehospital care. The Which Early ST-elevation myocardial infarction Therapy (WEST) study (10), also echoed by a previous study (11), demonstrated that paramedic-based PHM is safe and effective within our health care system. Based on these findings, PHM has been implemented in the Edmonton (Alberta) region as a ‘standard of care’.

There is limited information regarding barriers to PHM at the systems level and paramedics’ attitudes toward this treatment approach (12–14). Indeed, there is little known about opinions of the health care team (eg, cardiologists, emergency department physicians and nurses) involved in the care of ST elevation MI (STEMI) patients regarding PHM. Thus, capturing the perceptions and attitudes of stakeholder groups may provide a holistic perspective on underlying barriers. Moreover, establishing a unified understanding of PHM and a commitment to an integrative approach to care may enhance the program’s success. Accordingly, we explored paramedics’, cardiologists’ and emergency department physicians’ and nurses’ perceptions, attitudes and knowledge of prehospital care of acute STEMI patients using qualitative methods.

METHODS

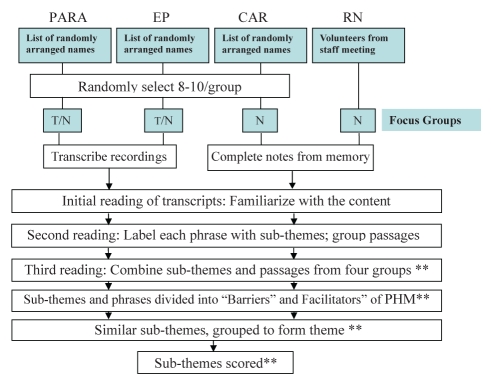

Qualitative research makes a prominent contribution in areas where little research has been conducted, and hypothesis or theory testing cannot be performed because variables relating to the concept of interest have not been identified (15). Although the results are not as generalizable due to the inherent subject and context-dependent nature, qualitative methods obtain detailed and in-depth data that cannot be obtained with quantitative methods. Therefore, within the present study, a standard focus group methodology was used because of its high internal validity, speed of completion and flexibility to explore unanticipated issues (16,17). A summary of the methods described below is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1).

Focus group procedure from recruitment of participants to analysis of data. Emergency room nurses (RN) were recruited after a scheduled nurses’ staff meeting. The cardiology group had a tape-recording failure. **Reviewed by two reviewers to ensure consistency of content and analysis. CAR Cardiologists; EP Emergency physicians; N Notes; PARA Paramedics; PHM Prehospital management; T Tape-recorded

Setting and participant sampling

The present study was conducted within the metropolitan Edmonton area, with an estimated population of 1,014,000. There are two tertiary care hospitals with cardiac catheterization laboratories and percutaneous coronary intervention facilities, and four community hospitals with fully equipped coronary care units (CCUs). There are six (Edmonton, Leduc, Parkland, St Albert, Strathcona and Wetaskiwin) participating ambulance authorities that transport STEMI patients to these hospitals. Within the region, PHM of STEMI entails paramedic-based patient identification and assessment, completion of a reperfusion checklist, transmission of the 12-lead electrocardiogram for remote physician interpretation, and consultation with a cardiologist or emergency physician to confirm diagnosis and appropriate treatment (ie, PHF or prehospital triage for primary percutaneous coronary intervention).

Although there are no set guidelines for size of focus groups, five to 10 participants are generally recommended (18–20) to allow all members to contribute to the discussion and present a full range of views. Recognizing the potential for volunteer dropout, the acquisition of eight to 10 participants for each focus group session was proposed. Inclusive lists of groups of interest (paramedics, cardiologists and emergency physicians) from Edmonton and surrounding regions were obtained. From these inclusive lists, 24 potential participants per group were randomly selected and placed in numerical sequence. They were contacted and invited to participate in the focus group session sequentially until eight agreed to participate. Emergency room nurses were recruited following a scheduled nurses’ staff meeting.

The focus group sessions were scheduled to be 1 h to 2 h in duration to leave ample time for discussion and to be considerate of participants’ time. Four focus group sessions (one per group) were conducted to maximize the range of emergent issues related to PHM (21–23).

Focus group session and data analysis

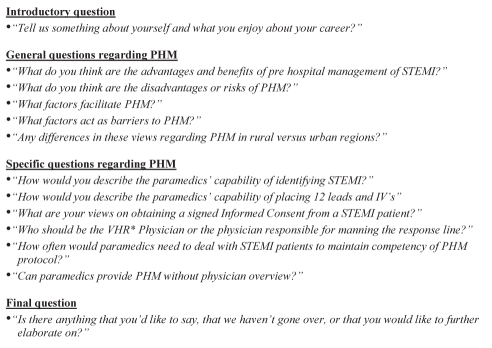

During each of the focus group sessions, the participants’ opinions and beliefs regarding advantages and disadvantages as well as facilitators of and barriers to PHM were explored using a funneling technique. A question map was used to ensure that the groups covered a list of predefined issues (Figure 2) (19). Introduction of issues other than the predefined issues were permitted. Discussions were tape-recorded with concomitant field note-taking by the moderator. Transcribed information was analyzed using the constant comparative method in which multiple cycles of reading and coding of information yielded common themes (19). Subthemes were analyzed and scored according to criteria described in Table 1. Generated themes were validated using investigator triangulation (24).

Figure 2).

Funneling technique for focus group discussions. *Vital Heart Response (VHR) is the established prehospital management (PHM) program in Edmonton, Alberta. IV Intravenous; STEMI ST elevation myocardial infarction

TABLE 1.

Criteria for scoring subthemes

| Score | Criteria |

|---|---|

| + + | Clear, decisive view that is supported by others in the group. A view that also stimulates supportive discussion |

| + | A view that is brought up at least once. A view that stimulates other varying or balancing views |

| 0 | No views or opinions brought up by a group on a particular matter |

The University of Alberta’s Human Research Ethics Board provided ethical approval for the present study.

RESULTS

Six paramedics and four representatives from each hospital staff group participated. Focus group sessions lasted 2 h for paramedics, 1 h for emergency physicians, 45 min for cardiologists and 30 min for emergency room nurses.

Six factors that facilitate and five that are barriers to PHM are described below and summarized in Table 2. Selected supportive quotes to respective subthemes are presented below, with the source identified by group: paramedic (PARA), emergency physician (EP), cardiologist (CARD) and emergency nurse (RN). The ‘informed consent’ theme was not scored due to numerous discrepant perspectives emerging within and between groups; instead, it is presented independently.

TABLE 2.

Categorized themes and scored subthemes

| Barriers to prehospital managment (PHM) |

Score |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EP | PARA | CARD | RN | |

| 1. Knowledge of PHM process and protocol | ||||

| a. Lack of knowledge (or uncertainty) on aspects of the PHM protocol | + + | 0 | + | + |

| b. Perception that focus on PHM will be robbing from trauma | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| c. Perception that some hospital staff are unaware of PHM protocol | 0 | + + | 0 | 0 |

| d. Incongruency in literature or understanding of literature on myocardial infarction (MI) therapy | 0 | + + | 0 | 0 |

| e. Lack of knowledge of paramedic team protocols | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Practical aspects of PHM | ||||

| a. Perception that PHM will have no effect and/or will increase overcrowding in emergency department | + | + | 0 | + |

| b. Perception that MI patients will avoid taking emergency medical services due to cost | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| c. Perception that patients with MI will avoid going to the hospital due to wait times | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| d. Perception of lack of communication between paramedic and hospital | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Ownership of and taking responsibility for patient | ||||

| a. Negative perceptions about steps in the protocol (ie, PHM-diagnosed patient stopping at the emergency department for triage) | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| b. Perceptions on ownership of and taking responsibility for patient | + + | + | + | + |

| 4. Capability and interest of paramedic to provide PHM | ||||

| a. Skepticism (lack of trust) in some paramedics to carry out PHM effectively | + + | + + | 0 | 0 |

| b. Perception that some paramedics in rural areas are not capable of effectively providing PHM | 0 | 0 | 0 | + + |

| c. Perception of paramedic misdiagnosis | + + | + | 0 | + |

| d. Perception that paramedics’ inability to handle complications (or situations outside of protocol) will cause problems | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| e. Perception that some physicians may be resistant to PHM | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| f. Perception that some paramedics will be disappointed by Vital Heart Response physicians’ decisions | 0 | + + | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Technological assistance | ||||

| a. Perception of technological failures inhibiting ability to manage patient | + | + + | + | 0 |

| b. Knowledge of technical problems as a barrier to PHM | 0 | + + | 0 | 0 |

| Score | ||||

| Facilitators of PHM | EP | PARA | CARD | RN |

| 1. Benefits of PHM | ||||

| a. Knowledge that expertise is brought to patients with PHM | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| b. Perception that PHM may increase the flow of in-hospital patient treatment | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| c. Perception that PHM may decrease in-hospital workload | + | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| d. Perception that PHM may increase the number of people taking ambulances during a heart attack with public awareness programs | + | + | + | 0 |

| e. Perception that PHM process will benefit patients even if there are contraindications to drug use | 0 | + | + | 0 |

| f. Perception that PHM will decrease cost to health care system | 0 | + | 0 | + |

| g. Knowledge of clinical benefit (including reducing time to treatment) | + + | + + | + | + |

| 2. Medical overview and team relations | ||||

| a. Integrating key players to form a team approach (accepting paramedic as ‘equals’) or (understanding the importance of a good physician-paramedic relationship) | + | + + | 0 | 0 |

| b. Perception that medical overview is needed to ensure effective treatment of patient in the field | + + | + + | + | + + |

| c. Perception that paramedic may have better access to cardiologists than emergency physicians | 0 | + + | 0 | 0 |

| d. Perception of sound communication between paramedic and hospital | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| e. Perception that rural paramedics have a closer relationship than urban paramedics with respective hospitals | 0 | 0 | + + | 0 |

| 3. Practical aspects of PHM process and protocol | ||||

| a. Knowledge of some emergency medical service protocols | + + | + + | 0 | 0 |

| b. Perception that a simplified protocol for the stakeholders will facilitate PHM | 0 | 0 | + + | + |

| c. Knowledge of real-life field experience or knowledge of source of delays to treatment | 0 | + + | 0 | 0 |

| d. Perception that placing cardiologists at peripheral sites will facilitate PHM | + | 0 | 0 | + |

| e. Perception that setting benchmark times for steps in the protocol is needed | 0 | 0 | + + | 0 |

| f. Consistency of ST elevation MI treatment protocol (prehospital versus inhospital) | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| 4. Training and regular maintenance of competency | ||||

| a. Perception that continuous training (to maintain skills) by paramedics will facilitate PHM | + + | + + | + + | + + |

| b. Perception that simulations may complement real-life exposure to MI cases to maintain competency | + + | + + | 0 | 0 |

| c. Perception that increasing the quality of paramedic education program is needed to promote confidence | 0 | + + | 0 | 0 |

| d. Knowledge that one must be critical of results published in the literature | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Paramedics’ willingness and capability to manage acute MI patients | ||||

| a. Perception that paramedics are capable of providing prehospital care to acute MI patients | + + | + + | + | + + |

| b. Paramedics’ ability to handle bleeding (complication) | + | 0 | + + | 0 |

| c. Paramedic will find added responsibility of providing PHM to be professionally rewarding | 0 | + + | + | 0 |

| d. Knowledge that PHF is protocol-driven and perception that ST elevation MI is not too difficult to treat | + + | + + | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Technological assistance | ||||

| a. Perception that technology is a positive factor in PHM | 0 | + | 0 | 0 |

| b. Confidence in electrocardiogram technology and transmission | 0 | 0 | + | 0 |

See Table 1 for scoring criteria. CARD Cardiologists; EP Emergency physicians; PARA Paramedics; RN Emergency nurses

Facilitators of PHM of STEMI patients

Benefits of PHM:

All groups acknowledged that PHM reduced myocardial damage and decreased the chances of mortality by achieving early reperfusion. Benefits beyond direct patient care in areas such as cost to the health care system and patients’ time off work were also envisaged (Table 2).

Medical overview and team relations:

Physician overview of PHM was seen as a necessity because paramedics lacked the training and knowledge to make independent decisions regarding the type of therapy warranted for a particular patient. “As a paramedic there’s nothing in my education that even prepares me for looking at two people and going okay for this guy, which is a better option primary PCI or thrombolytics in the field?” (PARA). The medical overview process, however, was seen as a team approach, based on consultation: “it’s the team approach which is coming in medicine…I think it’s using the team players to their maximum and paramedics have the ability to do this, let’s use their talent” (EP). Paramedics felt that rural paramedics formed closer working relationships with hospitals in rural areas than in urban settings.

Practical aspects of the PHM process and protocol:

Knowledge of the PHM protocol among hospital staff would allow for an accurate assessment of a patient’s condition and demonstrate respect for the paramedic profession. Emergency physicians demonstrated knowledge of the type of equipment and medication available to paramedics. Paramedics presented various sources of transportation delays, such as traffic, warranting PHM. Setting benchmark times in the protocol was an idea suggested by cardiologists. Emergency nurses and emergency physicians believed that staffing cardiologists at peripheral sites would be more effective than triaging in emergency departments.

Training and regular maintenance of competency:

Regular maintenance of PHM knowledge and skills, especially through MI case simulations, was seen by all groups as an essential factor to improving PHM. One emergency physician stated that “…so as long as you have consistent training with…I guess it’s called continuing training, because, you know, it’s a new program and everyone is hot for it, if you don’t pick up a STEMI [patient] in a year, you know it’s all just going to be gone, so your skills will be gone…right.” Participants also felt that frequent training sessions would help maintain the quality of service provided by paramedics: “And it comes down to QI [quality improvement] – you catch people who might not be doing a good job, you let them know. Comes down to ongoing training” (PARA).

Paramedics’ willingness and capability to manage acute MI patients:

All groups expressed general confidence in paramedic professionals’ ability to provide effective PHM, while their ability to handle complications was acknowledged by cardiologists and emergency physicians: “Reperfusion arrhythmias or V-Fib [ventricular fibrillation] can be handled by paramedics” (CARD). In addition to knowledge and skill, the protocol-driven nature of PHM was also a contributing factor to capability: “it is protocol driven, so, it doesn’t rely as much on the differing experience and ‘have you ever seen this before?’ It’s going to be a ‘this case, this history, this ECG… – you know, ‘are the vitals between this and this’” (EP). Paramedics felt that their ability to save lives through PHM was professionally rewarding. “Now with identifying patients and…CPR or giving the drugs in the field, and it makes a huge difference to patient care. And that’s rewarding, ’cause I think all of us are here to help people as best we can…” (PARA).

Technological assistance:

Overall, groups were content with the use and quality of the technological assistance available to expedite STEMI confirmation by a physician including the prehospital 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) and mechanism of transmission. “And we’ve had some excellent cases in the city where, they started, they did the serial 12 leads and the MI showed up” (PARA). “ECG quality is generally good” (CARD). “Even though baselines are sometimes off, it’s workable” (CARD).

Barriers to PHM of STEMI patients

Knowledge of the PHM process and protocol:

According to paramedics, some hospital staff, especially emergency nurses, lacked knowledge of the PHM protocol, resulting in a frustrating working environment because hospital staff were not prepared for an incoming patient. This opinion was supported by the nurses, who emphasized having an insufficient knowledge of the protocol.

Emergency physicians demonstrated some uncertainty in their knowledge while debating the basis on which paramedics decide to bring an MI patient to the emergency room versus the catheterization laboratory. In addition, no objections from colleagues occurred when one cardiologist suggested using preloaded tenecteplase needles, indicating a lack of knowledge that tenecteplase is a powder requiring reconstitution with water at the time of use. Paramedics also indicated that some of their colleagues felt that the literature reported contradictory conclusions about STEMI treatment approaches, making them unwilling to administer PHM (Table 2).

Practical aspects of PHM of STEMI:

Emergency physicians discussed the possibility that PHM increases crowding in the emergency departments, especially at the tertiary centres. Paramedics felt that overcrowding did not occur due to PHM. However, they expressed concerns about MI patients’ reluctance to take an ambulance due to cost and a lack of urgency to get themselves to the hospital. On the other hand, one paramedic suggested that the long wait times at the hospital deterred some MI patients from coming to the hospital at all. Educating the public on the benefits of calling an ambulance was seen as an important concept, but paramedics felt that it was currently ineffective. One paramedic asked if “…there’s a bigger role for us, the paramedics, in that process [public education]…?”

Paramedics also discussed instances of a break in the chain of communication between the paramedics and hospital staff during patient transport to the hospital. “Typically sometimes what happens is, you get to emerg [emergency department] and somebody didn’t contact somebody (yeah), and then you’re sitting there going ‘well I have this patient that’s enrolled in this study, or, Vital Heart [STEMI patient]’ and they’re [hospital staff] going ‘mmm, we don’t know anything about him’” (PARA).

Ownership and responsibility of patient care:

Varying perspectives on ownership and responsibility for PHM patients were shared. Cardiologists felt that the responsibility for manning the response line belonged to the emergency physicians, while emergency physicians felt the opposite. Emergency nurses and paramedics felt that both physician groups should be responsible.

Emergency groups believed that PHM patients should be taken directly to the CCU or catheterization laboratory, instead of being triaged in the emergency department.

Paramedics lacked a sense of ownership over their patients. “I treated this guy at his worst. And now I can’t even find out if he is still at the hospital” (PARA).

Capability and interest of paramedics to provide PHM:

Doubts were raised concerning the ability of all paramedics to provide PHM. According to one emergency physician, “the opinion of outside… sources are not always trusted or the state of the patient as relayed to them [colleague physicians] by consult or phone is not always trusted”. This group also expressed concern in paramedics’ inability to appropriately identify STEMI on ambiguous symptoms or ECG readings, resulting in valid cases to be overlooked. Emergency nurses perceived rural paramedics to make more identification and treatment errors because they were paid less and received poorer standards of training than urban paramedics. “Paramedic services in the rural areas, like from a 100 miles out, may not be strong in identifying STEMI” (RN). “It might not be appropriate for them to carry out PHM. Their learning curve is greater” (RN). “It also comes down to how much they get paid. The ones in the rural areas get paid half as much, so their quality of training and capability of providing care isn’t as good” (RN).

Paramedics suggested that some colleagues’ apprehension toward PHM may stem from being ‘chastised’ by their preceptors for making a mistake. In addition, they felt that while colleagues with more experience were willing to manage STEMI, they were less confident about using new technologies. On the other hand, recent graduates were more likely to be technologically inclined, but less confident to manage STEMI.

Technological assistance:

Emergency physicians and paramedics recalled instances of ECG transmission failure to the response-line; “…I’ve seen crews where they tried twice to fax and it didn’t work, and it’s like ‘[forget] this’.” (PARA). On the other hand, paramedics also felt that the failure of some paramedics to use the technology appropriately limited PHM implementation.

Informed consent

All but one person argued against obtaining signed informed consent from patients during PHM because it was believed to be redundant to the perceived ‘implied consent’ associated with calling 911, and infeasible because patients were distressed. Groups also noted the absence of informed consent for in-hospital fibrinolysis and questioned its necessity if PHM was a ‘standard of care’.

However, it was recognized that consent was currently in place to safeguard against possible liabilities; “who knows, it could’ve been driven by our management. That’s a liability risk management from their point” (PARA). Cardiologists and paramedics suggested that if consent were to remain as part of PHM, it would need to be succinct.

DISCUSSION

Successful integration of PHM of STEMI, including PHF in the ‘real-world’ setting, requires understanding barriers and establishing a unified understanding between stakeholders. In our study, a general consensus emerged among stakeholders that PHM reduces time to treatment and improves the health outcomes of STEMI patients. Groups beleived that most paramedics were capable of executing appropriate patient identification, eligibility checklist completion and therapy administration, while medical overview was important to confirm MI diagnosis. Formal intermittent reviews of PHM by paramedics and hospital staff in direct care of these patients was seen as a facilitator of the program. Although the concept of patient ownership was raised consistently by all the stakeholders, dissonance existed in areas such as triage of patients to the emergency room and appropriate physician staffing of the remote response line. Incongruency in perceptions between groups and lack of knowledge of the process by some group members may be barriers to acceptance. Instances of technological failures during ECG transmission were identified as one of the barriers.

Resonating with other studies (12–14), paramedics in our study were enthusiastic about the benefits of PHM to the patients and to the paramedic profession, despite countervailing issues. In the survey conducted by Humphrey et al (13), the majority of paramedics overestimated the risks of mortality and morbidity associated with fibrinolysis. These misperceptions may make the paramedics less inclined to provide PHM; as such, implementing appropriate means to correct these misconceptions may eliminate a barrier to PHM. This study did not explore issues regarding technology and paramedic-hospital staff relations, which were perceived to be important aspects of PHM in our study. The focus group study by Cox et al (14) reported primarily on elements of paramedics’ perception of their professional status because the participants were not exposed to PHM. Paramedics felt that PHM would foster a united working relationship with physicians and increase their professional status. Paramedics in our study felt that PHM of STEMI would make their image as patient care providers more credible to the public, who would in turn be more willing to use their services. The increase in credibility was attributed, in part, to the quality of paramedic education. As such, this sense of pride and interprofessional cooperation needs to be developed through innovative programs.

Paramedics in the study by Price et al (12) felt that the added responsibility of PHM should warrant a pay increase. Distinctively, the paramedics in our study found motivation in the opportunity to improve patient outcomes. In fact, they suggested that introducing a registry to track patients’ outcomes would increase their sense of patient ownership.

An enhanced understanding of both the prehospital and in-hospital realm by emergency physicians suggests that this group should be included in efforts to enhance integrative and collaborative practices. Ironically, emergency physicians felt that PHM patients should bypass the emergency department and be sent directly to the CCU or catheterization laboratory. This view stems, in part, from the perception that PHM may increase crowding in the emergency departments. Overcrowding and resource scarcity have become key barriers to patients receiving timely care (24–26). Although ambulance diversion systems are typically used to manage ambulance traffic during periods of overcrowding, the resulting increased travel distance to the next closest hospital inevitably results in treatment delay (27,28). With the advent of PHM, the opportunity to improve patient outcomes with administration of definitive treatment, despite the possibility of ambulance diversion, becomes apparent.

The cardiologists suggested imposing benchmarks for key steps in the PHM protocol. Although this may be a reasonable approach in an ideal setting, where many of the scenarios are similar, paramedics indicated that there are many uncertainties and unpredictable events that occur during an emergency call. It has been suggested that focusing on benchmark times may be perceived as taking the priority away from providing quality care (29).

Emergency nurses’ lack of trust in the rural paramedics’ ability to perform PHM as effectively as their urban counterparts may be rooted in their experience, or may reflect pre-existing biases or inadequate interaction with this group. Addressing this issue is important as programs expand, not only in urban centres across North America, but rural centres where PHM will have the largest impact with respect to time reduction according to participants.

Discussion of the signed informed consent process was also unique to our study, with the majority of participants against it. The impractical nature of obtaining signed consent from a distressed patient and the fact that it was also deemed unnecessary if PHM was ‘standard of care’ were identified in our work. Offering public awareness programs highlighting the benefits and process of PHM of STEMI may help address these issues. Rationalizing the necessity of the consent form to the stakeholders may patch a void in knowledge and prevent a possible barrier.

Limitations

We used a qualitative method of study design for the present study, accepting that there are limitations to this approach. Bias may be present because participants volunteered to participate despite being randomly selected. Second, due to a technological failure, one group was not tape-recorded and the session was analyzed using notes. Third, we introduced an approach of quantifying qualitative data for ease of tabulation when considering four different study groups, and accept that there are challenges and limitations to this approach. Finally, we recruited four to six participants per group in the present study. Although this group size is more comfortable for participants, it limits the range of experience (29,30).

Implications

Results from the present study can have a direct impact on establishing stakeholder buy-in by addressing any barriers or misconceptions that emerged from the focus groups.

An effective PHM protocol can be designed for all stakeholders to ensure a unified understanding. In addition, a public awareness program, based on the focus group, can also be implemented to educate patients at risk of STEMI to call an ambulance for ensuing chest pain.

CONCLUSION

North America lacks a widespread collaborative approach to PHM of STEMI patients that incorporates both PHF and direct triage for primary percutaneous coronary intervention. As such, identifying barriers and facilitators to a PHM program is paramount in improving both existing PHM strategies and enhancing implementation of new PHM programs. Against this background, we used qualitative research methods in our study, where clinical trials fall short, to understand barriers and facilitators by capturing the views of key stakeholders in the care of STEMI patients. Stakeholders identified a variety of issues within different aspects of the PHM process, providing policymakers with a basis to investigate innovative educational programs and protocol changes to provide timely patient care.

REFERENCES

- 1.Statistics Canada Canada e-Book<http://www43.statcan.ca/> (Version current at August 7, 2009).

- 2.Fu Y, Goodman S, Chang W-C, Van De Werf F, Granger CB, Armstrong PW, for the ASSENT 2 Trial investigators Time to treatment influences the impact of ST-segment resolution on one-year prognosis: Insights from the assessment of the safety and efficacy of a new thrombolytic (ASSENT-2) trial. Circulation. 2001;104:2653–9. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrow DA, Antman EM, Sayah A, et al. Evaluation of the time saved by prehospital initiation of reteplase for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Results of The Early Retavase-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (ER-TIMI) 19 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:71–7. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01936-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raitt MH, Maynard C, Wagner GS, Cerqueira MD, Selvester RH, Weaver WD. Relation between symptom duration before thrombolytic therapy and final myocardial infarct size. Circulation. 1996;93:48–53. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger PB, Ellis SG, Holmes DR, Jr, et al. Relationship between delay in performing direct coronary angioplasty and early clinical outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction: Results from the global use of strategies to open occluded arteries in Acute Coronary Syndromes (GUSTO-IIb) trial. Circulation. 1999;100:14–20. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstrong PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction – executive summary: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:588–636. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000134791.68010.FA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallentin L, Goldstein P, Armstrong PW, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenecteplase in combination with the low-molecular-weight heparin enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin in the prehospital setting: The Assessment of the Safety and Efficacy of a New Thrombolytic Regimen (ASSENT)-3 PLUS randomized trial in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2003;108:135–42. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081659.72985.A8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison LJ, Verbeek PR, McDonald AC, Sawadsky BV, Cook DJ. Mortality and prehospital thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction: A meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:2686–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.20.2686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Welsh RC, Chang W, Goldstein P, et al. ASSENT-3 PLUS Investigators. Time to treatment and the impact of a physician on prehospital management of acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: Insights from the ASSENT-3 PLUS trial. Heart. 2005;91:1400–6. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.054510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong PW, WEST Steering Committee A comparison of pharmacologic therapy with/without timely coronary intervention vs. primary percutaneous intervention early after ST-elevation myocardial infarction: The WEST (Which Early ST-elevation myocardial infarction Therapy) study. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1530–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chittari MS, Ahmad I, Chambers B, Knight F, Scriven A, Pitcher D. Retrospective observational case-control study comparing prehospital thrombolytic therapy for ST-elevation myocardial infarction with in-hospital thrombolytic therapy for patients from same area. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:582–5. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.020271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Price L, Keeling P, Brown G, Hughes D, Barton A. A qualitative study of paramedics’ attitudes to providing prehospital thrombolysis. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:738–41. doi: 10.1136/emj.2005.025536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humphrey J, Walker A, Hassan TB. What are the beliefs and attitudes of paramedics to prehospital thrombolysis? A questionnaire study. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:450–1. doi: 10.1136/emj.2004.016998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox H, Albarran JW, Quinn TQ, Shears K. Paramedics’ perceptions of their role in providing prehospital thrombolytic treatment: Qualitative study. Accid Emerg Nurs. 2006;14:237–44. doi: 10.1016/j.aaen.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chenitz W, Swanson J. Qualitative Research Using Grounded Theory: Qualitative Research in Nursing. Menlo Park: Addison-Wesley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hassel K, Hibbert D. The use of focus groups in pharmacy research: Processes and practicalities. J Soc Adm Pharm. 1996;49:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith F. Focus groups and observation studies. Int J Pharmacol Pract. 1998;6:229–42. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan DL, editor. Successful Focus Groups: Advancing the Stage of the Art. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krueger RA, editor. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 2nd edn. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measure scales: A practical guide to their development and use. 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Norwood SL. Research strategies for advanced practice nurses. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sandelowski M. Focus on research methods: Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–40. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yorkston KM, Baylor C, Klanser E, et al. Satisfaction with communicative participation as defined by adults with multiple sclerosis: A qualitative study. J Commun Disord. 2007;40:433–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Denzin NK. The Research Act: A theoretical introduction to Sociological Methods. Chicago: Aldine Publications Co; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fernandes CM, Daya MR, Barry S, Palmer N. Emergency department patients who leave without seeing a physician: The Toronto Hospital experience. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;24:1092–6. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(94)70238-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rondeau KV, Francescutti LH. Emergency department overcrowding: The impact of resource scarcity on physician job satisfaction. J Healthc Manag. 2005;50:327–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fottler MD, Ford RC. Managing patient waits in hospital emergency departments. Health Care Manag. 2002;2:46–61. doi: 10.1097/00126450-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schull MJ, Morrison LJ, Vermuelen, Redelmeier DA. Emergency departments overcrowding and ambulance transport delays for patients with chest pain. Can Med Assoc J. 2003;168:277–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price L. Treating the clock and not the patient: Ambulance times and risks. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:127–30. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.015651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krueger RA, Casey MA. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]