Abstract

We investigated the hypothesis that transmigration drives monocyte transcriptional changes. Using Agilent whole human genome microarrays, we identified over 692 differentially expressed genes (2×, P<0.05) in freshly isolated human monocytes following 1.5 h of transmigration across IL-1β-stimulated ECs compared with untreated monocytes. Genes up-regulated by monocyte transmigration belong to a number of over-represented functional groups including immune response and inhibition of apoptosis. qRT-PCR confirmed increased expression of MCP-1 and -3 and of NAIP following monocyte transmigration. Additionally, quantification of Annexin V binding revealed a reduction in apoptosis following monocyte transmigration. Comparison of gene expression in transmigrated monocytes with additional controls (monocytes that failed to transmigrate and monocytes incubated beneath stimulated ECs) revealed 89 differentially expressed genes, which were controlled by the process of diapedesis. Functional annotation of these genes showed down-regulation of antimicrobial genes (e.g., α-defensin down 50×, cathelicidin down 9×, and CTSG down 3×). qRT-PCR confirmed down-regulation of these genes. Immunoblots confirmed that monocyte diapedesis down-regulates α-defensin protein expression. However, transmigrated monocytes were functional and retained intact cytokine and chemokine release upon TLR ligand exposure. Overall, these data indicate that the process of monocyte transmigration across stimulated ECs promotes further monocyte recruitment and inhibits monocyte apoptosis. Unexpectedly, following transmigration, monocytes displayed reduced antimicrobial protein expression.

Keywords: IL-1β, endothelial cells, cationic antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) below.

Introduction

Monocytes are phagocytic cells that play a key role in inflammation. In response to infection, these cells migrate out of the bloodstream and differentiate into macrophages that activate the innate immune response or DCs that activate the adaptive immune response. Monocyte migration to a site of inflammation begins with rolling along activated ECs, followed by firm adhesion to ECs, and finally, diapedesis across the endothelium toward a chemoattractant. One mechanism of EC activation is exposure to IL-1β, which induces expression of E-selectin, ICAM1, and VCAM1 on the endothelial surface [1]. Monocytes interact with these adhesion molecules, leading to rolling and firm adhesion to the endothelium [2,3,4]. Interaction with adhesion molecules has been shown to induce outside-in signaling events within leukocytes, which may lead to downstream changes in leukocyte transcription [5,6,7].

Activation of ECs through exposure to IL-1β also induces release of cytokines and other secreted factors (e.g., MIPs, MCPs, and fractalkine) [1], which have been shown to stimulate monocyte activation and recruitment [8,9,10]. During diapedesis, monocytes undergo changes in shape and interact with molecules found in EC junctions. Monocytes bind to junctional adhesion molecules and PECAM1 on the EC surface during diapedesis via LFA1 and PECAM1, respectively [4]. This binding may induce inside-out signaling within the monocyte [11]. All of the steps in transmigration may contribute to downstream changes in monocytes, which lead to inflammatory resolution or pathogenesis.

To understand the effects of transmigration on monocyte gene expression, we used microarrays to identify transcriptional changes in freshly isolated human monocytes that had transmigrated across a layer of IL-1β-stimulated ECs. Control conditions were used to further characterize which steps of transmigration are responsible for inducing these changes. Microarray analysis revealed that monocyte transmigration promotes further leukocyte recruitment, induces expression of genes involved in the inhibition of apoptosis, and reduces gene expression of antimicrobial proteins. These findings were confirmed with qRT-PCR, immunoblots, and apoptosis assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and monocyte isolation

Pooled HUVECs were purchased from Lonza (Switzerland) and cultured in HUVEC media, composed of M199 media (Mediatech, Manassas, VA, USA) containing 20% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA), 50 U/mL penicillin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, USA), 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco), 2 mM L-glutamine (Mediatech), 2.5 U/ml heparin (American Pharmaceutical Partners, Schaumburg, IL, USA), and 50 μg/ml endothelial mitogen (Biomedical Technologies, Stoughton, MA, USA). Passage 3–4 HUVECs were seeded at 50,000 cells/cm2 onto porcine gelatin-coated (0.2% wt/vol in PBS) polycarbonate cell-culture inserts (diameter=75 mm) containing 3 μm pores (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) and cultured until confluent at 37°C in the presence of humidified 5% CO2.

Monocytes were isolated from whole blood obtained from healthy adult donors according to an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol, in which all participants gave written, informed consent. Blood was drawn into citrate buffer anticoagulant and combined with an equal volume of 6% Dextran 70 solution (B. Braun, Bethlehem, PA, USA). This mixture was layered over lymphocyte separation media (1.078 g/mL, Cellgro, Manassas, VA, USA) and centrifuged for 30 min at 400 g. Following centrifugation, PBMCs were obtained from the interface, which formed between the lymphocyte separation media and saline solution. To remove platelets, PBMCs were rinsed twice by centrifugation in PBS at 250 g for 10 min. Monocytes were negatively selected from the PBMCs using a MACS monocyte isolation kit II (Miltenyi Biotec, Germany) with slight modifications to the manufacturer’s protocol. For 30 mL blood, PBMCs were pelleted and resuspended in 88 uL MACS buffer (0.5% HSA and 2 mM EDTA in PBS). FcR solution and antibody cocktail (30 μL each), as provided in the monocyte isolation kit, were added to the PBMCs. In addition, 1 μL each of biotinylated CD2 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and CD42b (GeneTex, San Antonio, TX, USA) antibodies were added to the PBMCs, and the mixture was incubated at 4°C for 10 min. Following this incubation period, 65 uL magnetic beads, as provided by Miltenyi Biotec, and 85 μl MACS buffer were added to the PBMCs with an additional 15-min incubation period at 4°C. PBMCs were then rinsed and resuspended in MACS buffer. Other cell types were removed from the monocytes by passing the cell mixture over a LS column placed in a MACS magnetic separator (Miltenyi Biotec). Monocytes were collected in the flow-through from the magnetic column. Purified monocytes were maintained in MEM with 0.5% HSA at 37°C until application to HUVEC and used within 2 h following isolation. In this procedure, CD2 and CD42b antibodies were necessary additions to the antibody cocktail to remove platelets and a small number of lymphocytes, which remained when the unmodified manufacturer’s protocol was used. Monocyte populations were assessed by Wright-Giemsa staining of cytospin preparations and found to be >95% pure (Shandon Cytospin).

Experimental protocol

Microarray analysis of monocyte responses to transmigration across stimulated ECs

Twenty-four hours after the ECs reached confluence, the media were replaced with HUVEC media containing 100 pg/ml IL-1β. Seven hours later, stimulated ECs were washed thoroughly three times with MEM. Then, the insert with the ECs was transferred to a new agarose-coated tissue-culture dish. Ten million freshly isolated monocytes in MEM with 0.5% HSA were placed above the stimulated ECs for 1.5 h. Following a 1.5-h incubation, monocytes that successfully transmigrated were collected (Fig. 1C, “TM”). As a control, monocytes that were applied above ECs but failed to transmigrate were collected (Fig. 1C, “UMA”). As another control, monocytes that were placed on agarose beneath stimulated ECs for 1.5 h, but never allowed to contact the ECs physically, were collected (Fig. 1B, “UMB”). As a final control, untreated monocytes were collected from an agarose-coated tissue-culture dish following a 1.5-h incubation period (Fig. 1A, “UNT”).

Figure 1.

Four monocyte populations collected for microarray and downstream analysis. (A) Untreated monocytes (UNT) were collected following 1.5 h incubation on agarose-coated tissue-culture dishes in MEM with 0.5% HSA. (B) Monocytes [unmigrated below (UMB)] were collected following 1.5 h incubation on agarose-coated tissue-culture dishes beneath IL-1β-stimulated HUVECs grown on polycarbonate cell-culture inserts containing 3 μm pores. These monocytes have been exposed to EC secretions that have diffused into the lower chamber but have not contacted ECs directly. (C) Monocytes that failed to transmigrate [unmigrated above (UMA)] during a 1.5-h incubation with IL-1β-stimulated HUVECs grown on cell-culture inserts were collected. These monocytes have contacted stimulated ECs and been exposed to EC secretions. Monocytes that transmigrated (TM) during 1.5 h incubation with IL-1β-stimulated HUVECs grown on cell-culture inserts were collected. These monocytes have undergone the process of diapedesis in addition to being exposed to EC secretions and contacting stimulated ECs directly.

Prior to RNA isolation, monocyte populations were purified further using CD105 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), according to the manufacturer’s protocol to remove contaminating ECs, which made up 3–5% of the cell population. Effectiveness of this purification step was measured by performing the transmigration protocol using freshly isolated monocytes labeled with Cell Tracker Orange (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and ECs labeled with Cell Tracker Green (Invitrogen). Flow cytometry was used to assess purity of the monocyte population and indicated <1% contamination following the EC removal step. This procedure was applied to all monocyte samples, irrespective of whether they were incubated with ECs, to control for any changes induced by the purification process.

Following this purification step, cells were counted with a Beckman Coulter Z2 particle count and size analyzer to determine percent transmigration. RNA and protein were isolated with TRI-zol (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, followed by DNA removal using an RNA cleanup kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). RNA quantity and quality were assessed by loading 1 μl sample RNA onto a RNA 6000 Nano chip (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and analyzing with an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer to determine the amount and integrity of RNA recovered. Monocyte samples having an RNA integrity number of 7.5 or greater, and at least 250 ng total RNA was used for microarray experiments; transmigrated (n=3), unmigrated above (n=3), unmigrated below (n=4), untreated (n=4).

Assessment of monocyte transmigration across unstimulated ECs

Monocytes were applied to unstimulated ECs in the same manner as described previously for IL-1β-stimulated ECs. Following a 1.5-h incubation, monocytes that successfully transmigrated were collected. Monocytes that were applied above ECs but failed to transmigrate were also collected. Monocyte populations were purified further using CD105 Microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec), as described previously. Following this purification step, cells were counted with a Beckman Coulter Z2 particle count and size analyzer to determine percent transmigration.

Assessment of monocyte DEFA3 mRNA expression in response to LOS

Monocyte transmigration assays across IL-1β-stimulated ECs were performed as described previously with the addition of 50 pM Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B LOS, a well-defined TLR4-myeloid differentiation protein-2 ligand [12], in the media reservoir beneath IL-1β-stimulated ECs. Monocytes were collected, purified, and assayed for DEFA3 mRNA expression.

Assessment of cytokine release induced by LOS stimulation

Monocyte transmigration assays across IL-1β-stimulated ECs were performed as described previously. Following collection and purification of untreated, transmigrated, unmigrated above, and unmigrated below samples, monocytes were incubated with or without 50 pM LOS in RPMI (Mediatech) with 10% FBS (Hyclone) for 20 h at 37°C. Supernatants were collected and stored at –20°C for future measurements of cytokine release. TNF-α, IL-8, and IL-6 release in supernatants collected from each of the experimental conditions were assayed using Duoset human ELISAs (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), according to the manufacturer’s protocol as described previously [12].

Analysis of monocyte responses to firm adhesion and diapedesis

Monocyte transmigration assays across IL-1β-stimulated ECs were performed as described previously with the addition of 20 μg/ml PECAM1-blocking antibody (HEC7; Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA), applied along with monocytes to inhibit diapedesis but allow firm adhesion. Four populations of monocytes were collected: untreated, transmigrated, unmigrated above, and adherent monocytes, which remained bound to the stimulated ECs. Following removal of contaminating ECs, monocytes were assayed for DEFA3 mRNA expression.

Microarrays

Microarray hybridization and imaging were performed at the Morehouse School of Medicine Functional Genomics Core Facility (Atlanta, GA, USA). Briefly, RNA and universal human reference RNA (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) were linearly amplified to cRNA using a low RNA input fluorescent linear amplification kit (Agilent). Cy5-labeled cRNA for each sample was competitively hybridized with Cy3-labeled reference cRNA to a 44k whole human genome microarray (Agilent), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were dried under nitrogen and scanned on an Agilent DNA microarray scanner. Microarray images were analyzed with Agilent feature extraction software. GeneSpring 7.3 software was used to analyze the microarray data with one-way ANOVA, assuming equal variances, followed by a post hoc Student-Neuman-Keuls test. Differentially expressed genes were identified as those that had changes of at least twofold and adjusted Pvalues of <0.05. Microarray data have been deposited in National Center for Biotechnology Information’s GEO (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and are accessible through the GEO series Accession Number GSE14027.

Functional grouping of differentially expressed genes

Lists of differentially expressed genes were uploaded to DAVID and subjected to functional annotation clustering at medium class stringency to identify enriched biological themes [13]. GO biological process annotations were used to perform this functional clustering. Lists of up-regulated and down-regulated genes were uploaded separately to DAVID to identify enriched pathways and map differentially expressed genes to these pathways.

qRT-PCR

Total RNA from each sample was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using SuperScript II (Invitrogen). cDNA was purified with Micro Bio-Spin P-30 chromatography columns (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA) and diluted in RT-PCR-grade water (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Predesigned PCR primers and Quantitect SYBR Green PCR master mix were purchased from Qiagen. Primers were added to the master mix at a ratio of 1:5. Each reaction was performed with 4 μl diluted cDNA and 6 μl primers in the master mix. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed on a LightCycler 2.0 (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with a 15-min activation step at 95°C; 50 cycles at 94°C for 15 s, 55°C for 20 s, 72°C for 20 s; and a ramped melting cycle. Fold changes were determined using the ΔΔ-comparative threshold method. Statistical differences in fold changes were assessed with one-way ANOVA followed by a post-hoc Tukey multiple comparison test. qRT-PCR was used to verify gene expression from RNA isolated from three independent monocyte transmigration experiments.

Immunoblotting

For detection of α-defensin or β-actin protein expression, 15 μg protein or 5 μg protein, respectively, was blotted onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Pall Life Science, East Hills, NY, USA). After blocking with 5% nonfat dry milk, membranes were probed with mouse α-defensin mAb (GeneTex) or mouse β-actin mAb (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA). Bound primary antibodies were labeled with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies and detected with ECL Plus (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA). Net intensities of α-defensin expression were quantified by densitometry with the Kodak EDAS 1D imaging system (Kodak, Rochester, NY, USA) and normalized to β-actin net intensities. Immunoblots were performed using protein isolated from four separate time-course experiments, and statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA, followed by a post hoc Tamhane test for unequal variances. The post hoc Tamhane test was chosen over the Tukey multiple comparison test, as Bartlett’s test for equal variances showed unequal variances, indicating that the Tukey test is inappropriate [14, 15].

Apoptosis assays

Cells were collected from each of the experimental conditions and washed in cold PBS. Freshly isolated monocytes were treated for 3 h with 2 μM staurosporine or 2 mM hydrogen peroxide as positive controls for apoptosis and necrosis, respectively. Cells were then stained with R-PE-conjugated Annexin V and SYTOX® Green using the Vybrant apoptosis kit, No. 8 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Annexin V binds to phosphatidyl serine on the outside of the cell membrane and is an indicator of monocyte apoptosis. SYTOX® Green labels DNA in monocytes that have a compromised cell membrane and is an indicator of late-stage apoptosis or necrosis. Samples were analyzed for staining by flow cytometry, measuring the fluorescence emission at 530 nm and 575 nm. The percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc., Ashland, OR, USA).

RESULTS

Monocyte transmigration and recovery

When monocytes were placed above stimulated ECs for 1.5 h, 21 ± 5% of the applied monocytes were collected from the dish beneath the ECs as transmigrated monocytes. An additional 22 ± 3% of the applied monocytes failed to transmigrate and were collected from above the stimulated ECs. Monocytes that were firmly adherent to the stimulated ECs make up an additional 17 ± 5% of the applied monocytes. Annexin V and SYTOX® Green staining identified an additional 3 ± 1% of the monocytes as dead, based on positive staining for Annexin V and SYTOX® Green. Analysis of monocyte recovery revealed that loss during monocyte collection from the agarose-coated dish accounted for 15 ± 2% of the applied monocytes, and monocyte loss during the purification procedure to remove contaminating ECs accounted for an additional 20 ± 3% of the applied monocytes. When monocytes were placed above unstimulated ECs for 1.5 h (n=4), <1% transmigrated into the dish beneath the ECs.

Global effects of the transmigration process

Comparison of gene expression in transmigrated monocytes with gene expression in untreated monocytes revealed up-regulation of 489 genes and down-regulation of 203 genes following transmigration. The top 10 up-regulated and down-regulated genes are shown in Table 1. Interestingly, the most highly up-regulated genes, MCP-1 and -3, are both chemokines known to strongly attract monocytes. Thus, transmigrating monocytes may be involved in recruiting other monocytes through the production of chemokines. The most highly down-regulated genes, DEFA3 and cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide, are both peptides that have known antimicrobial activity. A list of all of the differentially expressed genes in transmigrated monocytes compared with untreated monocytes can be found in Supplemental Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Top 10 Up- and Down-Regulated Genes in Transmigrated Monocytes

| Gene symbol | Gene name | Fold change (TM vs. UNT) |

|---|---|---|

| CCL2 | MCP-1 | 14.8 |

| CCL7 | MCP-3 | 14.4 |

| TNIP3 | TNFAIP3-interacting protein | 13.6 |

| EMP1 | Epithelial membrane protein 1 | 13.6 |

| BATF | Activating transcription factor B | 9.1 |

| DMD | Dystrophin | 9.1 |

| IL2RA | IL-2RA | 8.7 |

| CTSL1 | Cathepsin L | 8.3 |

| THEX1 | 3′ histone exonuclease | 7.9 |

| LMNB1 | Lamin B 1 | 7.7 |

| CST6 | Cystatin 6 | 0.21 |

| NTF3 | Neurotrophin 3 | 0.20 |

| CNTROB | Centrobin | 0.19 |

| NKX2-3 | NK2 transcription factor-related, locus 3 | 0.19 |

| MUC8 | Mucin 8 | 0.18 |

| PLA2G4A | PLA2G4A | 0.17 |

| VIL1 | Villin | 0.17 |

| FANCI | Mitochondrial polymerase γ | 0.17 |

| LL37 | Cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide | 0.11 |

| DEFA3 | DEFA3 | 0.02 |

TNFAIP3, α-induced protein 3.

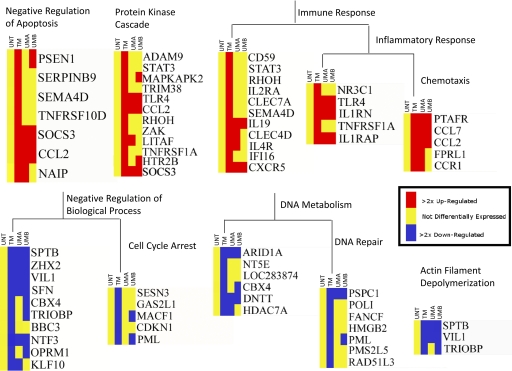

Functional annotation clustering was performed using DAVID to identify enriched biological themes or functional groups among these 692 up- and down-regulated genes. Genes identified as being down-regulated are involved in cell-cycle arrest, DNA metabolism, and actin filament depolymerization. Up-regulated genes are involved in the immune response, the protein kinase cascade, and inhibition of apoptosis. Genes associated with these functional groups are shown in Figure 2, and red indicates up-regulation, yellow no significant change in expression, and blue down-regulation. It should be noted that some genes are differentially expressed in all of the monocyte treatment conditions as compared with untreated monocytes [e.g., MCP-1 (CCL2) and SOCS3], and other genes are differentially expressed in only one or two of the monocyte treatment conditions as compared with untreated monocytes. This result indicates that some differentially expressed genes are responding to a stimulus that is found in all of the monocyte treatment conditions (i.e., cytokine secretions from IL-1β-stimulated HUVEC), and other differentially expressed genes are responding to stimuli that are only found in some of the monocyte treatment conditions (i.e., EC contact or diapedesis). A more complete examination of the individual effects of these stimuli follows.

Figure 2.

The process of transmigration affects genes belonging to a variety of functional groups. Over-represented functional groups up- or down-regulated by monocyte transmigration as compared with untreated monocytes are shown. Functional groups were identified by analysis of lists of up- or down-regulated genes with DAVID. Heat maps of genes belonging to identified functional groups were generated in Genespring 7.3. Yellow indicates no significant change in gene expression; red indicates up-regulation; and blue indicates down-regulation of gene expression.

qRT-PCR confirmation

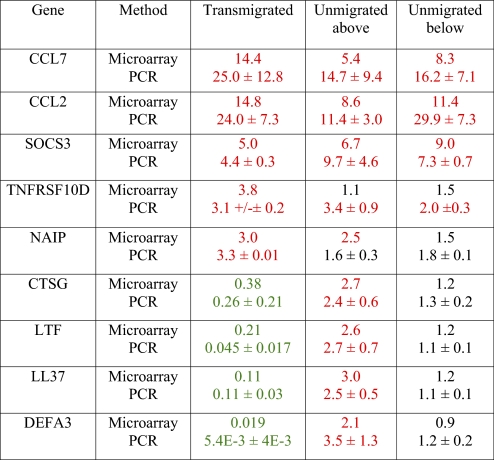

Five up-regulated genes and four down-regulated genes were selected for qRT-PCR confirmation of the microarray results. The five up-regulated genes were chosen for confirmation because of their inclusion in the Negative Regulation of Apoptosis functional group (Fig. 2). The four down-regulated genes were chosen for confirmation because of their inclusion in the defense response functional group (see “Effects of diapedesis” below). Patterns of differential expression, as observed by microarray analysis, closely resembled patterns of differential expression detected by qRT-PCR. A comparison of fold changes, as detected by microarray analysis and qRT-PCR, is shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Microarray and qRT-PCR Fold Changes

Average fold changes for microarray data were obtained from Genespring 7.3 following normalization to expression levels in untreated monocytes. For qRT-PCR data, fold changes represent the average ± sem for three experiments as compared with untreated monocytes. Red values indicate up-regulation of at least twofold, and green values indicate down-regulation of at least twofold.

Transmigration inhibits apoptosis

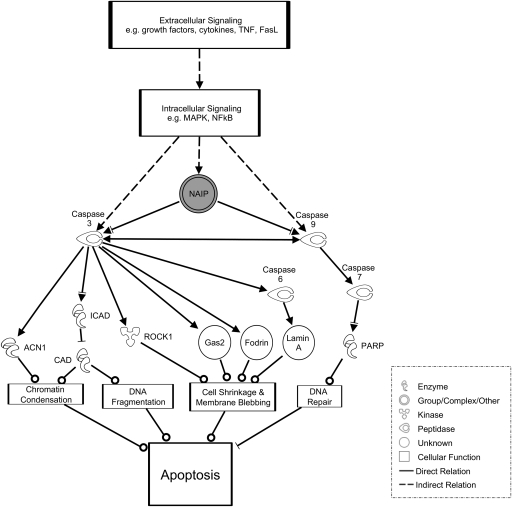

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis was used to map up-regulated genes belonging to the GO term “Negative Regulation of Apoptosis” to the apoptosis pathway. A portion of this pathway is shown in Figure 3; for the complete pathway, see Supplemental Figure 1. Apoptosis is shown at the bottom of Figure 3 and is preceded by chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, cell shrinkage, and membrane blebbing. These cellular activities are mediated by various proteins including ACN1, CAD, and GAS2. The activity of each of these proteins is regulated by caspase 3 and caspase 9. Further examination of Figure 3 reveals that NAIP inhibits caspase 3 and caspase 9 activity. The gray shading of NAIP indicates that in our microarray data, this gene was up-regulated in transmigrated monocytes compared with untreated monocytes. qRT-PCR confirmed up-regulation of NAIP in transmigrated monocytes as compared with untreated monocytes (Table 2). Significant increases in NAIP expression were not seen in monocytes incubated below stimulated ECs or in monocytes that failed to transmigrate.

Figure 3.

Transmigration causes differential expression of genes in the apoptosis pathway. Genes belonging to the Negative Regulation of Apoptosis functional group were mapped to the apoptosis pathway. Apoptosis is shown at the bottom of the pathway. Caspase 3 and caspase 9 are key enzymes in promoting apoptosis by activation through enzymatic cleavage of a number of proteins that control apoptotic functions, such as chromatin condensation, DNA fragmentation, and membrane blebbing. Both of these caspase genes are inhibited by NAIP, which is up-regulated in transmigrated monocytes compared with untreated monocytes, as indicated by the gray shading. Various intracellular and extracellular signaling pathways are involved in expression and inhibition of caspase 3, caspase 9, and NAIP. FasL, Fas ligand; ICAD, inhibitor CAD; ROCK1, Rho-associated coiled-coil protein kinase 1; PARP, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase.

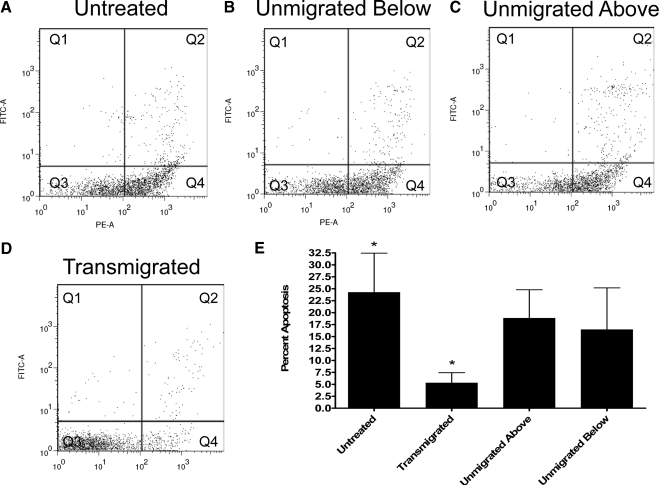

Functional assay of apoptosis

Apoptosis assays were performed on monocyte populations using Annexin V and SYTOX® Green labeling. Representative flow cytometry dot plots are shown in Figure 4, A–D. Immediately following monocyte isolation, 13% of monocytes were found in the apoptotic quadrant (Q4). Following incubation of monocytes on an agarose-coated dish for 1.5 h in MEM with 0.5% HSA and negative magnetic selection of the monocytes, ∼20% of these untreated monocytes were found in the apoptotic quadrant, Q4, with positive staining for Annexin V binding and without uptake of SYTOX® Green (Fig. 4A). Monocytes that failed to transmigrate (Fig. 4C) and monocytes incubated beneath stimulated ECs (Fig. 4B) contained 18% and 16% apoptotic cells, respectively. Following monocyte transmigration, only ∼5% of the monocytes were apoptotic (Fig. 4D). Quantification of apoptosis in each of the four monocyte-treatment conditions from four experiments is shown in Figure 4E, indicating that transmigrated monocytes have a significant reduction in apoptosis as compared with untreated monocytes. In all conditions, <5% of the monocytes fell within the necrotic quadrant (Q2), with positive staining for Annexin V binding and SYTOX® Green.

Figure 4.

Apoptosis is reduced in monocytes following transmigration. (A–D) Representative dot plots of R-PE-labeled Annexin V and SYTOX® Green-labeled monocytes from each of the four monocyte populations. Q1, No cells; Q2, necrotic or late apoptotic monocytes; Q3, live monocytes; Q4, apoptotic monocytes. (E) Quantitation of monocyte apoptosis in four experiments; bars indicate mean ± sem; *, P < 0.05.

Steps in transmigration process

Comparison of gene expression in transmigrated monocytes and untreated monocytes indicates that the monocyte transcriptome is altered by the process of transmigration; however, it does not allow for determination of which specific steps in the transmigration process are responsible for these changes. Control conditions were used to identify which steps of transmigration (i.e., exposure to endothelial secretions, monocyte-endothelial contact, or diapedesis) are responsible for altered monocyte gene expression.

Effects of IL-1β-induced endothelial secretions

We expected that a number of gene changes seen between transmigrated monocytes and untreated monocytes were induced by exposure to EC secretions resulting from IL-1β treatment of the ECs. In our studies, transmigrated monocytes (Fig. 1, TM), monocytes that failed to transmigrate (Fig. 1, UMA), and monocytes incubated beneath stimulated ECs (Fig. 1, UMB) were all exposed to EC secretions. We identified 119 genes that were differentially expressed in all of these monocyte conditions as compared with untreated monocytes (Supplemental Table 2). Fold changes were similar among all of the conditions for 99% of the differentially expressed genes, indicating that exposure to EC secretions is responsible for differential expression of these genes. Functional grouping using DAVID revealed that monocyte exposure to EC secretions causes up-regulation of genes involved in a number of biological processes including immune response, cellular component organization, and signal transduction (Table 3). Of particular interest is up-regulation of CCL2, CCL7, TLR4, IL-19, and CXCR5, which are all cytokines or cytokine receptors that may be involved in further leukocyte recruitment and activation. Exposure to EC secretions causes down-regulation of genes involved in intracellular signaling and transcription (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Functional Groups Associated with Up-Regulation by EC Secretions

| (TM/UNT) | Fold change (UMA/UNT) | (UMB/UNT) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immune system response | |||

| CCL2, MCP-1 | 14.8 | 8.6 | 11.4 |

| CCL7, MCP-3 | 14.4 | 5.4 | 8.3 |

| IL1RN, IL-1RN | 6.9 | 4.8 | 3.5 |

| IL19, IL-19 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.2 |

| CXCR5, chemokine (c-x-c motif) receptor 5 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 3.5 |

| TLR4, TLR4 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.2 |

| Cellular component organization | |||

| EMP1, epithelial membrane protein 1 | 13.6 | 6.4 | 5.5 |

| CISH, cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein | 7.1 | 9.0 | 8.4 |

| SOCS3, SOCS3 | 5.0 | 6.7 | 9.0 |

| PDSS1, prenyl diphosphate synthase, subunit 1 | 6.2 | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| KIF15, kinesin family member 15 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 4.6 |

| FGD4, five, rhogef, and ph domain containing | 3.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| Signal transduction | |||

| RSPO3, r-spondin 3 homolog | 3.9 | 4.3 | 2.5 |

| CCL2, MCP-1 | 14.8 | 8.6 | 11.4 |

| CCL7, MCP-3 | 14.4 | 5.4 | 8.3 |

| TLR4, TLR4 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.2 |

| IL19, IL-19 | 3.6 | 2.9 | 2.2 |

| CISH, cytokine-inducible SH2-containing protein | 7.1 | 9.0 | 8.4 |

| FGD4, five, rhogef, and ph domain containing | 3.0 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| SOCS3, SOCS3 | 5.0 | 6.7 | 9.0 |

| MCTP2, multiple c2 domains, transmembrane | 6.5 | 4.1 | 2.8 |

| CXCR5, chemokine (c-x-c motif) receptor 5 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 3.5 |

| CD69, cd69 antigen, early T cell activation antigen | 4.8 | 4.9 | 5.7 |

SH2, Src homology 2.

TABLE 4.

Functional Groups Associated with Down-Regulation by EC Secretions

| (TM/UNT) | Fold change (UMA/UNT) | (UMB/UNT) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal transduction | |||

| OPRK1, opiod receptor, κ 1 | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.21 |

| MAP4K5, MEK kinase kinase 5 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.39 |

| guanine nucleotide-binding regulatory protein | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.40 |

| SFN, stratifin | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.39 |

| MED16, thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 5 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.43 |

| CENTG2, centaurin, γ 2 | 0.46 | 0.34 | 0.35 |

| GRM5, glutamate receptor, metabotropic 5 | 0.37 | 0.46 | 0.37 |

| SPTB, spectrin, β, erythrocytic | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.38 |

| DAB2IP, ngap-like protein | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| NTRK2, neurotrophic tyrosine kinase, receptor, type 2 | 0.46 | 0.38 | 0.44 |

| FRAT2, frequently rearranged in advanced T cell lymphomas 2 | 0.43 | 0.45 | 0.48 |

| Regulation of transcription | |||

| ZNF367, zinc finger protein 367 | 0.24 | 0.29 | 0.35 |

| SETD2, huntingtin-interacting protein b | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.35 |

| HOXC5, homeobox C5 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.32 |

| BHLHB5, basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class b, 5 | 0.32 | 0.37 | 0.33 |

| KIAA2018 | 0.47 | 0.36 | 0.29 |

| ZHX2, zinc fingers and homeoboxes 2 | 0.35 | 0.44 | 0.35 |

| MED16, thyroid hormone receptor-associated protein 5 | 0.40 | 0.32 | 0.43 |

| PSPC1, paraspeckly component 1 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 0.50 |

| GLIS2, glis family zinc finger 2 | 0.44 | 0.42 | 0.41 |

| ARID1A, at rich interactive domain 1a | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.47 |

Effects of monocyte-endothelial contact

In our system, both transmigrated monocytes (Fig. 1, TM) and monocytes that failed to transmigrate (Fig. 1, UMA) had contact with ECs, and monocytes placed beneath ECs (Fig. 1, UMB) and untreated monocytes (Fig. 1, UNT) had no EC contact. Sixty-one genes were differentially expressed in monocytes that contacted ECs as compared with untreated monocytes (Supplemental Table 3). Of these 61 genes, 34 are up-regulated, and 27 are down-regulated. Signal transduction and the immune response are some of the functional groups associated with genes up-regulated by monocyte-EC contact. Lipid metabolism is one of the functional groups associated with the down-regulated genes (Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Functional Groups Associated with Differential Expression by Monocyte/EC Contact

| Fold change

|

||

|---|---|---|

| (TM/UNT) | (UMA/UNT) | |

| Signal transduction | ||

| GBG10, guanine nucleotide binding protein, γ 10 | 5.6 | 3.0 |

| MCTP2, multiple c2 domains, transmembrane 2 | 5.0 | 3.5 |

| SUCNR1, succinate receptor 1 | 2.4 | 3.5 |

| CCR1, chemokine (c-c motif) receptor 1 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| FPRL1, formyl peptide receptor-like 1 | 2.5 | 2.6 |

| IL4R, IL-4R | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| LITAF, LPS-induced TNF factor | 2.7 | 2.0 |

| PBEF, pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor 1 | 2.3 | 2.1 |

| Immune response | ||

| CCR1, chemokine (c-c motif) receptor 1 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| IL4R, IL-4R | 2.5 | 2.4 |

| CLEC4D, C-type lectin domain family 4, member D | 2.4 | 2.0 |

| Lipid metabolism | ||

| PLA2G3, PLA2G3 | 0.49 | 0.48 |

| ST3GAL6, st3 β-galactoside α-2,3-sialyltransferase 6 | 0.41 | 0.48 |

| PLA2G4A, PLA2G4A | 0.17 | 0.23 |

Effects of diapedesis

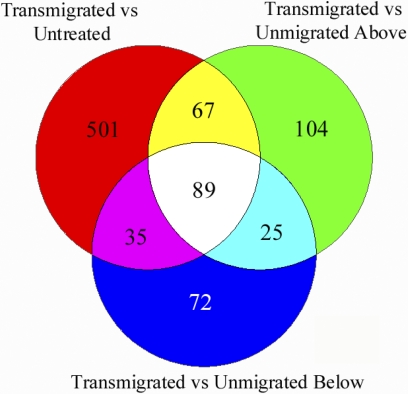

In our system, the only sample that went through diapedesis was transmigrated monocytes (Fig. 1, TM). Comparing transmigrated monocytes to all of the other conditions provides information about how the process of diapedesis alters monocyte transcription. The Venn diagram in Figure 5 indicates that when transmigrated monocytes are compared with untreated monocytes, monocytes that failed to transmigrate, and monocytes incubated beneath stimulated ECs, there are 89 genes that are found to be differentially expressed in all three of these comparisons. Eighty of these genes were up-regulated, and only nine were down-regulated (Supplemental Table 4). Functional grouping of these genes shows up-regulation of genes involved in cell differentiation and down-regulation of antimicrobial proteins (Table 6).

Figure 5.

Monocyte transmigration induces differential gene expression in comparisons with untreated monocytes, monocytes that failed to transmigrate (Unmigrated Above), or monocytes incubated below stimulated ECs (Unmigrated Below). This Venn diagram of genes that are differentially expressed in transmigrated cells as compared with other treatment conditions shows the overlapping genes in each of the comparisons. The 89 genes in the center of this Venn diagram are differentially expressed in transmigrated monocytes as compared with all of the other conditions. The primary difference between transmigrated monocytes and the other three monocyte populations is that transmigrated monocytes have gone through the process of diapedesis. This indicates that expression of these 89 genes is likely to be controlled by diapedesis.

TABLE 6.

Functional Groups Associated with Genes Differentially Expressed by Diapedesis

| Fold change (TM/UNT) | |

|---|---|

| Cell differentiation | |

| DICER1, dcr-1 homolog | 4.8 |

| PMCH, pro-melanin-concentrating hormone | 4.2 |

| TNFRSF10D, TNFRSF10D | 3.8 |

| ERBB4, v-erv-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4 | 3.8 |

| GLDN, gliomedin | 3.5 |

| RTN4RL1, reticulon 4 receptor-like 1 | 3.4 |

| HLA-DOA, MHC, class ii, do α | 2.1 |

| Signal transduction | |

| FCGR2B, fc fragment of igg, low-affinity iib, receptor | 6.4 |

| CD59, CD59 antigen, complement regulatory protein | 4.8 |

| PMCH, pro-melanin-concentrating hormone | 4.2 |

| RBJ, ras-associated protein rap1 | 3.9 |

| TNFRSF10D, TNFRSF10D | 3.8 |

| ERBB4, v-erv-a erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog 4 | 3.8 |

| GPR112, g protein-coupled receptor 112 | 3.7 |

| IL1RAP, IL-1R accessory protein | 3.6 |

| RASA2, ras p21 protein activator 2 | 3.3 |

| ADCY2, adenylate cyclase 2 | 2.1 |

| TRIM38, tripartite motif-containing 38 | 3.2 |

| MUSK, muscle, skeletal, receptor tyrosine kinase | 2.7 |

| FGD4, five, rhogef, and ph domain containing 4 | 2.3 |

| Defense response | |

| DEFA3, DEFA3 | 0.02 |

| LL37, cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide | 0.11 |

| LTF, LTF | 0.21 |

| CTSG, CTSG | 0.38 |

Antimicrobial proteins

Of the nine genes down-regulated by diapedesis, four are antimicrobial genes that are involved in nonoxidative killing of bacteria. These genes include DEFA3, cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (LL37), LTF, and CTSG. DEFA3, LL37, and CTSG are all peptides that have <30 kDa MW. LTF is a larger iron-binding protein with a 78-kDa MW. qRT-PCR confirmed down-regulation of these genes as shown in Table 2. Of these four antimicrobial genes, DEFA3 was the most down-regulated, with a change of ∼50 fold. A similar decrease in DEFA3 mRNA expression was seen in monocytes that transmigrated into a chamber containing 50 pM LOS (Supplemental Fig. 2), indicating that DEFA3 expression is not controlled by the presence or absence of TLR ligands. Although LOS did not regulate DEFA3 expression, transmigrated monocytes did retain intact responses to TLR engagement, as evidenced by release of cytokines into the supernatant following LOS exposure. Specifically, ELISA measurements of supernatant cytokine levels revealed significant increases in expression of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α following 20 h incubation with 50 pM LOS (Supplemental Fig. 3).

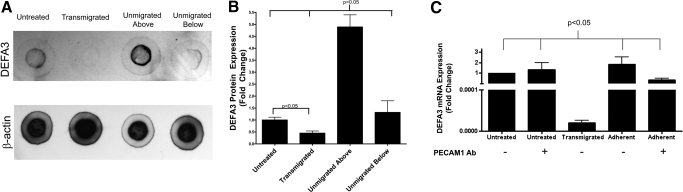

α-Defensin protein expression

As DEFA3 is the most down-regulated gene on the microarray, immunoblots were used to assess protein expression of DEFA3 and β-actin in each of the monocyte treatment conditions. Representative immunoblots are shown in Figure 6A. As with mRNA expression, protein expression of DEFA3 is decreased following transmigration and increased in monocytes that failed to transmigrate. Protein expression from five separate experiments was quantified and normalized to β-actin expression (Fig. 6B). This reveals ∼4.5-fold up-regulation of α-defensin expression in monocytes that failed to transmigrate as compared with untreated monocytes and approximately twofold down-regulation of α-defensin expression in transmigrated monocytes.

Figure 6.

α-Defensin protein expression is decreased in transmigrated monocytes and increased in monocytes that failed to transmigrate (Unmigrated Above), as assessed by immunoblots, and firm adhesion does not induce changes in α-defensin mRNA expression. (A) Representative α-defensin and β-actin immunoblots. (B) Quantitation of α-defensin protein expression normalized to β-actin expression, followed by normalization to expression in untreated monocytes. Bars represent mean expression ± sem for five experiments. (C) DEFA3 mRNA expression in untreated, transmigrated, and adherent monocytes in the presence or absence of PECAM1-blocking antibody (clone HEC7), which inhibits monocyte transmigration. Bars represent mean expression ± sem for three experiments.

Blocking of diapedesis

To differentiate between effects induced by monocyte firm adhesion and diapedesis, monocytes were applied to IL-1β-stimulated ECs in the presence or absence of 20 μg/mL PECAM1-blocking antibody (clone HEC7) to inhibit diapedesis, while allowing firm adhesion. As a control, untreated monocytes were incubated in the presence or absence of PECAM1-blocking antibody. When PECAM1-blocking antibody was present, <1% of the monocytes transmigrated into the dish beneath the stimulated ECs. Untreated monocytes, adherent monocytes, and transmigrated monocytes were collected and assayed for levels of apoptosis and DEFA3 mRNA expression. In the absence of PECAM1-blocking antibody, transmigrated monocytes have a significant drop in DEFA3 mRNA expression as compared with untreated monocytes (Fig. 6C). In the presence of PECAM1-blocking antibody, untreated monocytes have similar levels of DEFA3 expression as those incubated in the absence of PECAM1 antibody, indicating that the antibody itself does not impact DEFA3 expression. Adherent monocytes in the presence or absence of PECAM1 antibody have DEFA3 expression levels similar to that of untreated monocytes, indicating that firm adhesion does not cause decreases in DEFA3 expression.

DISCUSSION

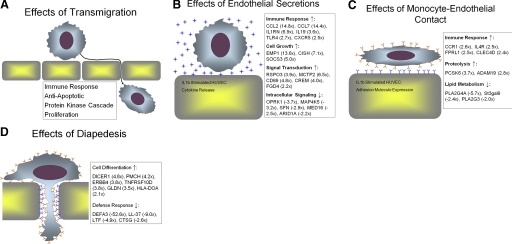

We found differential expression of 692 genes following monocyte transmigration across activated ECs. These differentially expressed genes indicate that transmigration induces transcription of cytokines, cytokine receptors, cell signaling genes, and genes that inhibit apoptosis (Fig. 7A). All of these findings indicate that transmigration induces a monocyte phenotype that is primed for response to extracellular cues that alter downstream functions of monocytes. Our microarray data also indicated that a number of genes involved in the inhibition of apoptosis are up-regulated following transmigration. Inhibition of apoptosis in transmigrated monocytes is supported by previous studies in neutrophils that have found decreased apoptosis following transmigration [16, 17]. Regulation of apoptosis is important for monocytes to prevent premature cell death and to allow monocytes to differentiate into macrophages and DCs. Our microarray data are supported by functional assays revealing reduced apoptosis in transmigrated monocytes and by qRT-PCR confirming up-regulation of NAIP, an inhibitor of apoptosis, following transmigration. We have interpreted these data to indicate that the process of transmigration leads to reduced apoptosis in monocytes. Another possibility is that apoptotic monocytes do not transmigrate as efficiently as nonapoptotic monocytes. However, if this were true, we would expect to see an increase in apoptosis-positive cells in the monocyte population that failed to transmigrate. Examination of Figure 4E reveals that the monocytes that failed to transmigrate, unmigrated above, do not have increased levels of apoptosis, thus making it unlikely that early apoptotic monocytes have reduced transmigration efficiency.

Figure 7.

Transmigration alters monocyte gene expression throughout the entire process. (A) Overall effects of monocyte transmigration. (B) Transcriptional effects of monocyte exposure to secretions derived from IL-1β-stimulated ECs. These genes showed differential expression in monocytes incubated below stimulated ECs, in monocytes that failed to transmigrate, and in transmigrated monocytes as compared with untreated monocytes. (C) Transcriptional effects of monocyte-EC contact. These genes were differentially expressed in monocytes that failed to transmigrate and in transmigrated monocytes as compared with untreated monocytes. (D) Transcriptional effects of diapedesis. These genes were differentially expressed in transmigrated monocytes as compared with untreated monocytes, monocytes that failed to transmigrated, and monocytes incubated below stimulated ECs. Only a portion of the differentially expressed genes for each of the steps of transmigration is shown in this diagram. Genes were chosen for display based on their inclusion in over-represented functional groups. Full lists of differentially expressed genes for each step of transmigration can be found in the supplemental tables. Fold changes listed represent the average fold change for each of the monocyte populations considered as compared with untreated monocytes.

In our system, ∼21% of monocytes transmigrated across stimulated ECs, and we collected sufficient amounts of RNA from these transmigrated monocytes for microarray analysis. Less than 1% of monocytes transmigrated across unstimulated ECs and into the dish below, and we were unable to analyze gene expression or monocyte function as a result of recovery of a very small number of monocytes. This level of transmigration across unstimulated ECs is lower than the ∼12% transmigration reported by Takahashi et al. [18] following 1 h incubation with unstimulated ECs grown on a collagen gel. Takahashi et al. [18] did not assess transmigration across a cell-culture insert but rather, monocyte transmigration into a collagen gel beneath ECs. In our system, we assessed transmigration across a layer of ECs, through a cell-culture insert with 3 μm pores, and into the chamber beneath the cell-culture insert. Thus, lower levels of transmigration across unstimulated ECs in our system may be explained by differences in the experimental setup.

We have also shown that monocyte transcription is affected by each of the steps of transmigration. Monocyte exposure to endothelial secretions leads to increased expression of genes involved in the immune response (Fig. 7B). The two most highly up-regulated genes in this study, CCL2 and CCL7, are both chemokines, which may promote further recruitment of monocytes. Previous studies have shown that monocyte coculture with naïve ECs causes increased expression of CCL2 [19, 20]. Takahashi et al. [19] showed that monocytes that failed to adhere to naïve ECs did not show increases in CCL2 staining, leading to the conclusion that monocyte-EC contact induces CCL2 up-regulation. In our study of monocyte interaction with stimulated ECs, similar levels of CCL2 up-regulation were seen in monocytes that had contacted the ECs directly and in monocytes incubated beneath the ECs. This indicates that there are at least two distinct mechanisms responsible for regulating CCL2 expression in monocytes incubated with naïve or IL-1β-stimulated ECs.

CCL2 and CCL7 belong to the Immune System Response functional group (Table 3). Up-regulation of genes within this group may be mediated by a number of cytokines secreted by IL-1β-stimulated ECs, including IL-6 and fractalkine [9, 21, 22]. An additional possibility is that IL-1β itself mediates up-regulation of these genes, and the source of IL-1β is unclear, as IL-1β-stimulated ECs are known to secrete IL-1β further [23], and residual IL-1β from EC stimulation may also be present. Except for IL1RN, increased expression of each of these genes would lead to increased accumulation of monocytes and other leukocytes within the tissue space during the acute cellular response phase of inflammation. Up-regulation of IL1RN, which inhibits the cellular response to IL-1β, may provide a mechanism for limiting long-term monocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation [24]. In addition to the immune system response, EC secretions induced expression of genes involved in cellular component organization and signal transduction. EC secretions also down-regulated signal transduction genes and genes involved in the regulation of transcription (Table 4).

Monocyte-endothelial contact leads to up-regulation of genes involved in signal transduction and the immune response (Fig. 7C). Among these genes, increased expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors, such as chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 [25], formyl peptide receptor-like 1 [26], and pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor [27], may enhance monocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation (Table 5). Monocyte-endothelial contact led to decreased expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism. In particular, PLA2G3 and PLA2G4A, enzymes involved in production of arachidonic acid, were down-regulated by monocyte-EC contact. Mishra et al. [28] showed recently that knockdown of PLA2G4A expression leads to a reduction in the rate of monocyte chemotaxis toward CCL2. Down-regulation of these genes may play an important role in regulating monocyte transmigration and preventing long-term monocyte accumulation within sites of inflammation.

Diapedesis induces expression of a number of genes involved in cell differentiation (Fig. 7D). We initially hypothesized that monocyte transmigration might drive differentiation toward a macrophage or DC phenotype. However, in our study, genes that are up-regulated by diapedesis and related to cell differentiation are not specific to monocyte differentiation. Recently, Lehtonen et al. [29] examined the gene expression of monocytes during the late and early stages of macrophage and DC differentiation. Comparison of our microarray data with genes differentially expressed in that study reveals that <5% of the genes differentially expressed in early macrophage or DC differentiation were differentially expressed in transmigrated monocytes. None of the common cell-surface markers for macrophages (CD14, CD64, CD163) or DCs (CD1a, CD1e, FceR1A/R2, CD1c, CD1b, CD205, CD209) were up-regulated at the mRNA level in our study, and Lehtonen et al. [29] saw up-regulation of mRNA expression for all of these genes at late stages of macrophage and DC differentiation. These data indicate that additional stimulation beyond transmigration is required for monocyte differentiation into macrophage or DC phenotypes. This finding is supported by the seminal study of Randolph et al. [30], which examined monocyte differentiation into DCs after a 48-h incubation period, in which monocytes transmigrated and then reverse-transmigrated back to the apical side of ECs grown on a collagen matrix. This work showed that monocyte reverse-transmigration initiates differentiation of monocytes to DCs, but further, stimulation is required for full differentiation to a mature DC phenotype. In our study, differentially regulated genes, which are involved in cell differentiation, may play an important role in mediating longer-term monocyte differentiation in response to transmigration and other extracellular stimuli.

Interestingly, our microarray data revealed that diapedesis leads to down-regulation of antimicrobial proteins (DEFA3, LL37, CTSG, LTF), which act as an important nonoxidative mechanism of bacterial killing in phagocytic cells [31]. qRT-PCR confirmed our microarray results for each of these proteins. Immunoblots of α-defensin expression were used to confirm that down-regulation of these genes extends to the protein level. This down-regulation of DEFA3 was seen in transmigrated monocytes, and firm adhesion did not induce down-regulation of DEFA3 (Fig. 6C). In addition to bacterial killing, antimicrobial proteins have a number of inflammatory effects, such as increased leukocyte chemotaxis [32], increased low-density lipoprotein accumulation within the endothelium, and interference with vascular smooth muscle cell function [33]. LL37, found in psoriatic lesions, has been shown to bind DNA from dead cells and form complexes that induce interferon production and thus, enhance progression of the disease [34]. In our system, it is possible that down-regulation of antimicrobial proteins following transmigration occurs as a cytoprotective effect to maintain endothelial homeostasis and limit monocyte recruitment.

Another possible interpretation of our data is that the monocytes that have higher expression levels of antimicrobial proteins are less efficient in transmigrating. In our experimental setup, it is impossible to rule out the possibility that the transmigrated monocytes represent a distinct population of monocytes that have an increased capacity for transmigration. However, if so, this population would represent a phenotype undescribed previously, comprising ∼21% of monocytes, a large proportion compared with the largest known subpopulation CD16+, which represents only 13% of all human monocytes [35]. This possibility, that the transmigrated monocytes represent a subset of monocytes that have lower expression of antimicrobial proteins and increased capacity for transmigration, is supported further by Figure 6B, which shows that monocytes that failed to adhere or transmigrate (unmigrated above) have a higher expression of DEFA3 than the untreated monocytes, indicating that the untreated monocytes may represent a mixture of the unmigrated-above and transmigrated subsets.

Inflammatory responses occur in sterile and septic environments. Our assay of monocyte transmigration induced by IL-1β stimulation of ECs is representative of monocyte transmigration, which is found in sterile conditions, such as atherosclerosis. Our data indicate that down-regulation of DEFA3 is not induced by a lack of bacterial signal (Supplemental Fig. 2). Our findings also indicate that monocytes do not exhibit tolerance to TLR ligands following transmigration or exposure to stimulated ECs. Transmigrated monocytes displayed significant increases in IL-8, IL-6, and TNF-α following exposure to LOS for 20 h. This cytokine release from transmigrated monocytes may play a significant role in atherosclerosis associated with bacterial infection [36].

Interestingly, untreated monocytes, which were not stimulated with LOS, had higher levels of basal IL-8 secretion than samples that had been exposed to IL-1β-stimulated ECs (unmigrated below, unmigrated above, and transmigrated; Supplemental Fig. 3). This decreased cytokine release from monocytes exposed to stimulated ECs indicates that monocytes develop tolerance to endothelial secretions and thus, have lower basal levels of cytokine production. This tolerance is independent of the TLR pathway, as indicated by significant increases in cytokine expression following monocyte stimulation with LOS.

In this study, we have shown that freshly isolated human monocytes have decreased levels of apoptosis following transmigration across stimulated ECs. We have also examined the effects of monocyte exposure to EC secretions, monocyte-EC contact, and diapedesis. These data indicate that monocytes respond to EC secretions with increased production of cytokines and other inflammatory genes. Monocyte-EC contact also impacted inflammatory gene expression with increased expression of cytokines and cytokine receptors. Finally, diapedesis led to differential expression of genes involved in cell differentiation and bacterial killing. These changes in monocyte gene expression likely serve to prime monocytes for further downstream functions and differentiation outside of the bloodstream. Additionally, many of the differentially expressed genes play roles in mediating or resolving inflammation. Future studies should address further validation of the microarray data and whether the gene expression changes we have documented can be extrapolated to the inflammatory state in vivo. As numerous pathologies, such as arthritis and atherosclerosis, result from chronic inflammation, it is especially important that transmigrated monocytes maintain a careful balance between inflammatory response and resolution.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants from the NIH (HL-70537, HL-18672). The authors acknowledge Morehouse School of Medicine Functional Genomics Core Facility, supported by NIH/National Center for Research Resources G12 RR00303, for performing microarray hybridization and scanning. We greatly appreciate the use of Dr. David S. Stephens’ laboratory for performing ELISAs (R01 AI033517). We also thank Dr. Lisa A. Schildmeyer for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ACN1=apoptotic chromatin condensation inducer 1, CAD=caspase-activated DNase, CTSG=cathepsin G, DAVID=Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery, DC=dendritic cell, DEFA3=defensin α 3, EC=endothelial cell, FBS=fetal bovine serum, GAS2=growth arrest-specific 2, GEO=Gene Expression Omnibus, GO=gene ontology, HSA=human serum albumin, HRP=horseradish peroxidase, HUVECs=human umbilical vein endothelial cells, ICAM1=intercellular adhesion molecule 1, IL1RN=IL-1R antagonist, LFA1=leukocyte function-associated Ag-1, LOS=lipooligosaccharide, LTF=lactoferrin, MCP=monocyte chemoattractant protein, MEM=minimum essential medium, MIP=macrophage inflammatory protein, PBMCs=peripheral blood lymphocytes, PBS=phosphate buffered saline, PECAM1=platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1, NAIP=neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein, NIH=National Institutes of Health, PLA2G3=phospholipase A2, group 3, qRT-PCR=quantitative RT-PCR, SOCS3=suppressor of cytokine signaling 3, TLR4=Toll like receptor-4, TNFRSF10D=TNF superfamily member 10D, VCAM1=vascular cell adhesion molecule-1

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

References

- Williams M R, Kataoka N, Sakurai Y, Powers C M, Eskin S G, McIntire L V. Gene expression of endothelial cells due to interleukin-1 β stimulation and neutrophil transmigration. Endothelium. 2008;15:73–165. doi: 10.1080/10623320802092443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon B, Ardavin C. Monocyte migration to inflamed skin and lymph nodes is differentially controlled by L-selectin and PSGL-1. Blood. 2008;111:3126–3130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-100610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukreti S, Konstantopoulos K, Smith C W, McIntire L V. Molecular mechanisms of monocyte adhesion to interleukin-1β-stimulated endothelial cells under physiologic flow conditions. Blood. 1997;89:4104–4111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imhof B A, Aurrand-Lions M. Adhesion mechanisms regulating the migration of monocytes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:432–444. doi: 10.1038/nri1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C, Simon D I. Integrin signals, transcription factors, and monocyte differentiation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney T S, Weyrich A S, Dixon D A, McIntyre T, Prescott S M, Zimmerman G A. Cell adhesion regulates gene expression at translational checkpoints in human myeloid leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10284–10289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181201398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Buul J D, Hordijk P L. Signaling in leukocyte transendothelial migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:824–833. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000122854.76267.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer M, von Stebut E. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:1882–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovic M, Laumonnier Y, Burysek L, Syrovets T, Simmet T. Thrombin-induced expression of endothelial CX3CL1 potentiates monocyte CCL2 production and transendothelial migration. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:215–223. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0907652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sozzani S, Locati M, Zhou D, Rieppi M, Luini W, Lamorte G, Bianchi G, Polentarutti N, Allavena P, Mantovani A. Receptors, signal transduction, and spectrum of action of monocyte chemotactic protein-1 and related chemokines. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:788–794. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.5.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangerfield J, Larbi K Y, Huang M T, Dewar A, Nourshargh S. PECAM-1 (CD31) homophilic interaction up-regulates α6β1 on transmigrated neutrophils in vivo and plays a functional role in the ability of α6 integrins to mediate leukocyte migration through the perivascular basement membrane. J Exp Med. 2002;196:1201–1211. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zughaier S M, Tzeng Y L, Zimmer S M, Datta A, Carlson R W, Stephens D S. Neisseria meningitidis lipooligosaccharide structure-dependent activation of the macrophage CD14/Toll-like receptor 4 pathway. Infect Immun. 2004;72:371–380. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.371-380.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis G, Jr, Sherman B T, Hosack D A, Yang J, Gao W, Lane H C, Lempicki R A. DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y, Tamhane A C. New York, NY, USA: Wiley; Multiple Comparison Procedures. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor G W, Cochran W G. Ames, IA, USA: Iowa State University Press; Statistical Methods. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Miller E J, Lin X, Simms H H. Transmigration across a lung epithelial monolayer delays apoptosis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Surgery. 2004;135:87–98. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(03)00347-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson R W, Rotstein O D, Nathens A B, Parodo J, Marshall J C. Neutrophil apoptosis is modulated by endothelial transmigration and adhesion molecule engagement. J Immunol. 1997;158:945–953. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Masuyama J, Ikeda U, Kitagawa S, Kasahara T, Saito M, Kano S, Shimada K. Suppressive role of endogenous endothelial monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 on monocyte transendothelial migration in vitro. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:629–636. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.5.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi M, Masuyama J, Ikeda U, Kasahara T, Kitagawa S, Takahashi Y, Shimada K, Kano S. Induction of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 synthesis in human monocytes during transendothelial migration in vitro. Circ Res. 1995;76:750–757. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.5.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas-Ecker S, Lindecke A, Hatzmann W, Kaltschmidt C, Zanker K S, Dittmar T. Alteration in the gene expression pattern of primary monocytes after adhesion to endothelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5539–5544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700732104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas P, Delfanti F, Bernasconi S, Mengozzi M, Cota M, Polentarutti N, Mantovani A, Lazzarin A, Sozzani S, Poli G. Interleukin-6 induces monocyte chemotactic protein-1 in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and in the U937 cell line. Blood. 1998;91:258–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano M, Sironi M, Toniatti C, Polentarutti N, Fruscella P, Ghezzi P, Faggioni R, Luini W, van Hinsbergh V, Sozzani S, Bussolino F, Poli V, Ciliberto G, Mantovani A. Role of IL-6 and its soluble receptor in induction of chemokines and leukocyte recruitment. Immunity. 1997;6:315–325. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello C A. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalovsky D, Paez Pereda M, Sauer J, Perez Castro C, Nahmod V E, Stalla G K, Holsboer F, Arzt E. The Th1 and Th2 cytokines IFN-γ and IL-4 antagonize the inhibition of monocyte IL-1 receptor antagonist by glucocorticoids: involvement of IL-1. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:2075–2085. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199807)28:07<2075::AID-IMMU2075>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber C, Weber K S, Klier C, Gu S, Wank R, Horuk R, Nelson P J. Specialized roles of the chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR5 in the recruitment of monocytes and T(H)1-like/CD45RO(+) T cells. Blood. 2001;97:1144–1146. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Migeotte I, Communi D, Parmentier M. Formyl peptide receptors: a promiscuous subfamily of G protein-coupled receptors controlling immune responses. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006;17:501–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luk T, Malam Z, Marshall J C. Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF)/visfatin: a novel mediator of innate immunity. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:804–816. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0807581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra R S, Carnevale K A, Cathcart M K. iPLA2β: front and center in human monocyte chemotaxis to MCP-1. J Exp Med. 2008;205:347–359. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen A, Ahlfors H, Veckman V, Miettinen M, Lahesmaa R, Julkunen I. Gene expression profiling during differentiation of human monocytes to macrophages or dendritic cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:710–720. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0307194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randolph G J, Beaulieu S, Lebecque S, Steinman R M, Muller W A. Differentiation of monocytes into dendritic cells in a model of transendothelial trafficking. Science. 1998;282:480–483. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5388.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harder J, Glaser R, Schroder J M. Human antimicrobial proteins effectors of innate immunity. J Endotoxin Res. 2007;13:317–338. doi: 10.1177/0968051907088275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim J J, Tewary P, de la Rosa G, Yang D. Alarmins initiate host defense. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;601:185–194. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-72005-0_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kougias P, Chai H, Lin P H, Yao Q, Lumsden A B, Chen C. Defensins and cathelicidins: neutrophil peptides with roles in inflammation, hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00332.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, Chatterjee B, Wang Y H, Homey B, Cao W, Su B, Nestle F O, Zal T, Mellman I, Schroder J M, Liu Y J, Gilliet M. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature. 2007;449:564–569. doi: 10.1038/nature06116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passlick B, Flieger D, Ziegler-Heitbrock H W. Identification and characterization of a novel monocyte subpopulation in human peripheral blood. Blood. 1989;74:2527–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mussa F F, Chai H, Wang X, Yao Q, Lumsden A B, Chen C. Chlamydia pneumoniae and vascular disease: an update. J Vasc Surg. 2006;43:1301–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.