Abstract

Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) is mainly reported in patients with bone metastasis from a variety of solid tumors and disseminated multiple myeloma receiving iv bisphosphonates therapy. These patients represent 95% of reported cases. The reported incidence of BRONJ is significantly higher with the iv preparations zoledronic acid and pamidronate while the risk appears to be minimal for patients receiving oral bisphosphonates. Currently, available published incidence data for BRONJ are based on retrospective studies and estimates of cumulative incidence range from 0.8% to 12%. The mandible is more commonly affected than the maxilla (2:1 ratio), and 60% of cases are preceded by a dental surgical procedure. The signs and symptoms that may occur before the appearance of clinical evident osteonecrosis include changes in the health of periodontal tissues, non-healing mucosal ulcers, loose teeth and unexplained soft-tissue infection. Although the definitive role of bisphosphonates remains to be elucidated, the alteration in bone metabolism together with surgical insult or prosthetic trauma appear to be key factors in the development of BRONJ. Tooth extraction as a precipitating event is a common observation in the reported literature. The significant benefits that bisphosphonates offer to patients clearly outbalance the risk of potential side effects; however, any patient for whom prolonged bisphosphonate therapy is indicated, should be provided with preventive dental care in order to minimize the risk of developing this severe condition. This article provides a review of current developments about the pathogenetic, clinical, management and preventive aspects of BRONJ.

Keywords: jaws, bisphosphonates, osteonecrosis

Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates are used widely for the treatment of bone metastasis (intravenous zolendronic acid or pamidronate), for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis (oral alendronate, risendronate, and ibandronate and intravenous ibandronate), for the treatment of Paget’s, and for the short- term management of acute hypercalcemia (intravenous zolendronic acid and pamidronate).

In 2003, after an alert initial observation by Wang et al. (1) at the University of California San Francisco, Rosenberg and Ruggiero (2), Marx (3) and Migliorati (4) have reported unusual findings of osteomyelitis – like lesions of the jaws in a set of patients affected by multiple myeloma and metastatic bone disease; subsequentely, several papers have confirmed the initial observations and called this condition as bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) (5-23). All the initial observations have pointed to the potential role of the intravenously administered bisphosphonates such as pamidronate and zoledronate. Additionally, BRONJ has been reported in a small number of patients (until now at least 35 cases) who had received oral non nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates for both cancer and non-cancer conditions (5, 10, 16, 24-27). Currently, available published incidence data for BRONJ are based on retrospective studies and estimates of cumulative incidence range from 0.8% to 12%.

It is of historical interest to mention that osteonecrosis of the jaws was observed in the 19thand early 20thcenturies in patients exposed to white phosphorus. At that time the disease was called phossy jaw or phosphorus necrosis and was mainly observed in people working in the matchmaking and fireworks factories or brass and war munitions industries (28). Amazingly, clinical descriptions of phossy jaw lesions overlap those reported today in cases of BRONJ (29).

Based on the available data, this review discusses the pathogenetic, clinical, management and preventive aspects of BRONJ.

Pathogenesis

From what it is known up to date it seems that the pathogenesis of BRONJ is due to a defect in jawbones physiologic remodelling and wound healing. The negative impact of bisphosphonates on bone physiology centers on osteoclast inhibition and apoptosis. The damaged osteoclast function affects the normal bone turnover and resorption process while additional negative effects of bisphosphonates also relate to depressed blow circulation in bones. In addition, bisphosphonates have the capability to inhibit endothelial cell function in vitro and in vivo and also demonstrate antiangiogenic properties because of their capacity to decrease circulating levels of the potent angiogenic factor VEGF (reviewed in16-18, 20, 30).

On the base of the current knowledge, BRONJ seems to be an exclusive ailment of the jaw bones. Most cases of BRONJ develop in patients who have undergone tooth extraction or other forms of surgical procedures; however a certain number of both edentulous or dentate patients has developed necrotic bone spontaneously. This apparent and exclusive involvement of the jaw bones may be a mirror of the uniqueness of the oral environment. It is well known that in normal conditions healing of a wound of the jaw bones (e.g., extraction socket) occurs quickly and without complication. Instead, in patients who have received tumoricidal irradiation (and/or other toxic agents) of the mandible and maxilla the healing process and the vascular supply of these bones are compromised, then even minor injury or inflammatory/infective diseases in these sites increases risk for osteonecrosis and osteomyelitis. In relation to the negative effects of bisphosphonates, it is conceivable that, because the jaw bones are sites of high bone turnover, these drugs concentrate within the bone tissue. This may partially explain the selective preference of bisphosphonates osteonecrosis for the jaw bones (reviewed in16-18, 20, 30).

Clinical and radiographic features

Patients with BRONJ are typically oncology patients with multiple myeloma or metastatic disease involving bone. The clinical aspects and behaviour of BRONJ show a striking resemblance to osteoradionecrosis with exposed bone and sequestration non-responsive to conventional surgical management. BRONJ may be asymptomatic for long time or may result in pain or exposed maxillary or mandibular bone (Fig.1). Typical signs and symptoms are pain, soft-tissue swelling and infection, loosening of teeth and draining fistula. Patients may have other symptoms such as difficulty in eating, speaking, and clinical signs such as trismus, halitosis and recurrent abscesses. Some patients may present with atypical symptoms such as “dull pain”, numbness, the feeling of “bigger jaw” or lower-lip paresthesia. The signs and symptoms that may occur before the appearance of clinically evident BRONJ include changes in the health of periodontal tissues, non-healing mucosal ulcers, loose teeth and unexplained soft-tissue infection (5, 9, 10). Chronic maxillary sinusitis secondary to BRONJ with or without oro-antral fistula can be the presenting symptom in patients with maxillary involvement.

Figure 1.

Extensive osteonecrosis in the maxilla with large sequestrum.

Since 2003, about 1000 cases of BRONJ of the jaws have been reported in the English-language literature, the majority associated with the use of iv bisphosphonates (19,20,22). Anatomic location may be unilateral or bilateral with 63% to 68% affecting only the mandible, 24% to 28% of cases involving only the maxilla, and 4.2% both jaws. The mean number of involved areas was 2.3 per each affected patient, with each site having an average size of 2 cm. Unusual cases of extragnatic location in the external auditory canal have been observed (31, Ficarra, personal observation). Ruggiero et al. (5) have observed pathologic fracture of either the maxilla or mandible in 8% of patients treated with nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates; rare cases of bilateral pathologic fractures of both jaws also have been reported. Extraoral fistula formation and sequestration through the skin are infrequently observed.

Radiographic alterations are not evident until there is significant bone involvement. Early stages of BRONJ may not reveal any significant changes on panoramic and periapical films. Late radiographic changes may mimic classic periapical inflammatory lesions or osteomyelitis. Other radiographic findings include non-healing extraction site, widening of the periodontal ligament space and osteosclerotic lamina dura (16-18, 20, 30). In cases of extensive bone involvement, areas of mottled bone similar to that of diffuse osteomyelitis become evident (Fig.2). In cancer patients some of these changes may raise the suspicion of myeloma or metastatic bone lesion (18). Involvement of the inferior alveolar canal can be associated with paresthesia of the lower lip. Bone scan with Tc-99m methylene diphosphonate often shows intense uptake in or around the lesional area, indicating active bone turnover.

Figure 2.

A panorex reveals the presence of a mottled zone of bone necrosis involving both the right maxilla and mandible. Note the large sequestrum in the right mandible.

Risk factors

Recent retrospective studies and review papers have identified and discussed several risk factors associated with BRONJ (5, 7, 9-23). Major factors are a history of dental extractions, duration of bisphosphonates treatment, and the type of bisphosphonates. The majority of reported BRONJ cases are associated with recent dentoalveolar surgery. This fact underlines the relevant importance of optimal good health and avoiding extractions especially in cancer patients receiving nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates. However, lesions may also occur spontaneously in non extractive sites such as dentate or non dentate areas or in areas covered by prosthetic appliances. The phenomenon of spontaneous appearance of BRONJ may be explained by the fact that, once “metabolically damaged” by the treatment with bisphosphonates, the jaw bones remain susceptible even to minor causative factors such as prosthetic trauma (5, 10).

The duration of bisphosphonates therapy is also an important factor which relates to the likelihood of developing BRONJ. In addition, the more potent nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, such as pamidronate and zoledronate, are significantly associated with the development of BRONJ than the oral bisphosphonates formulations (15-23). A recent prospective study assessed BRONJ in patients who received bisphosphonates since January 1997 (32). BRONJ was diagnosed in 17 of 252 patients. In addition, the study showed that the duration of iv bisphosphonate therapy appeared to be the most important risk factor.

A variety of etiological factors such as radiation and corticosteroid treatment, trauma, smoking, alcohol abuse, poor oral hygiene, herpes zoster, HIV infection and fungal infections, and predisposing conditions such as diabetes, osteopetrosis, fibrous dysplasia, may also affect wound healing of the jaws bones and also must be considered as possible cofactors (9, 17).

In summary, the fact that the majority of BRONJ cases are associated with the use of iv bisphosphonates for multiple myeloma and metastatic bone diseases suggests that dosage, length of treatment, and route of administration, as well as cofactors such as use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive agents, and dental surgery, could all be related to the incidence of this ailment.

Pathology

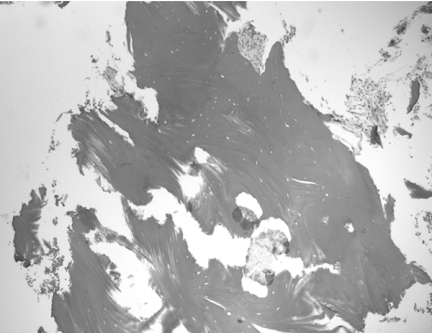

Diagnosis of BRONJ should be mainly based on clinical and radiographic criteria. Tissue biopsy is not always necessary and should be performed only if metastatic disease is suspected. At microscopic examination, the specimen shows areas of necrotic bone and debris and fibrinous exudates accompanied by a polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltrate (Fig.3). The nonvital bone exhibits loss of osteocytes from the lacunae, peripheral resorption and bacterial colonization. Scattered sequestra and pockets of abscess formation are common. These features are similar to those observed in chronic osteomyelitis (9, 16-18).

Figure 3.

High-power photomicrograph of biopsy tissue showing irregular fragments of nonvital bone that exhibit peripheral resorption, empty osteocytic lacunae and polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltrate (H&E, 400x).

Microbial cultures (aerobic and anaerobic) may provide identification of pathogens causing secondary infection. Microbiological investigations have detected a variety of oral pathogens such as Actinomyces, Enterococcus, Candida albicans, Haemophilus influenza, alpha-haemolytic streptococci, Lactobacillus, Enterobacter and Klebsiella pneumoniae, etc. (23). However, it is important to stress that cultures taken from an open sinus tract or exposed jaw bone may give misleading results because the isolates may include non-pathogenic microorganisms that are colonizing the site (33). Several authors have found a striking high presence of Actinomyces in necrotic bone areas and considered these pathogens to be involved in the chronic, non healing process of BRONJ (11, 18, 23, 34).

Case definition and staging of BRONJ

In order to establish rational treatment guidelines and collect clinical information to assess the prognosis in patients with BRONJ a working definition and staging system have been proposed by some researchers or association such as the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AAOMS) and the Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation (18, 22, 35).

To distinguish BRONJ from other delayed healing entities, the AAOMS (35) has adopted the following working definition. Patients may be considered to have BRONJ if all of the following three characteristics are present: a) past or current therapy with bisphosphonates; b) presence of exposed, necrotic bone in the maxillofacial region that has persisted for more than 8 weeks; and c) absence of history of radiation treatment to the jaw bones. The staging system reported here is the one which has been proposed by the AAOMS (TableI). In stage 1 the disease is characterized by exposed bone and absence of symptoms. Patients at this stage usually do not require treatment. However, it is relevant to note that some patients my have pain prior to the appearance of radiographic or clinical signs of overt BRONJ. Patients in stage 2 show exposed bone with associated pain. This stage requires antimicrobial therapies, pain control and superficial debridement to relieve soft tissue irritation. Stage 3 is characterized by exposed bone associated with pain, adjacent or regional soft tissue swelling and signs of secondary infection resistant to antibiotic treatment. These patients, because of voluminous sequestra, often require surgical intervention to debride necrotic bone.

Table I -.

Clinical Staging of BRONJ and treatment guidelinesa.

| Stages | Treatments guidelines |

|---|---|

| At risk category: no apparent exposed/necrotic bone in patients treated with either oral or iv bisphosphonates | No treatment indicated Patients education |

| Stage 1: exposed/necrotic bone in patients who are asymptomatic and have no evidence of infection | Antibacterial mouth rinse Clinical follow-up every 4 months |

| Stage 2: exposed/necrotic bone associated with infection. Presence of pain and erythema in the lesional area with or without purulent drainage irritation |

Treatment with broad-spectrum oral antibioticsb Antibacterial mouth rinse Pain control Superficial debridement to relieve soft tissue |

| Stage 3: exposed/necrotic bone in patients with infection and pain. Presence of one or more of the following: pathologic fractures, extraoral fistula, or osteolysis extending to the inferior border |

Antibacterial mouth rinse Antibiotic therapy and pain control Surgical debridement/resection for longer term palliation of infection and pain |

Modified from reference 35.

Penicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate potassium, metronidazole, cephalexin, clindamycin, fluoroquinolone.

Management guidelines for patients treated with bisphosphonates

Preventive aspects

It is important to underline that a strict collaboration between the dentist and the clinician/oncologist is mandatory in order to identify strategies to improve the care of patients treated with bisphosphonates. Until we have a better understanding of the role of bisphosphonates in the pathobiology of BRONJ it is a must that preventive measures be always taken in order to prevent the risk of developing this severe ailment. These include careful dental examination and mandatory extractions of candidate teeth with enough time allowed for healing in advance of the start of bisphosphonate treatment (9). Based on previous experience with osteoradionecrosis, it is highly advisable that bisphosphonates therapy should be delayed until there is adequate bone healing (18). Of great importance is the adoption of preventive measures such as dental caries and periodontal disease control, conservative restorative dentistry, avoiding dental implant placement, and the use of soft liners on dentures. This level of care must be continued indefinitely (9, 18).

In asymptomatic patients receiving iv bisphosphonates preventing dental diseases that may require dentoalveolar surgery is of pivotal importance. In these patients any procedure that may cause direct osseous damage must be avoided as well as placement of dental implants. Non-restorable teeth should be treated by removal of the crown and endodontic treatment of the root remnants.

Patients receiving oral bisphosphonates have a much lesser risk of developing BRONJ than those treated with iv bisphosphonates. The risk of BRONJ may be associated with longer duration of therapy (i.e., 3 years or more); however it is important to stress that this point needs further research and clarification. In general, these patients seem to have a less severe form of BRONJ and show a better response to stage-specific treatment strategies. In this group, dental extractions are not contraindicated. It is however recommended that patients should be adequately informed of the potential, although small, risk of defective bone healing. Although discontinuation of iv bisphosphonates in cancer patients has been recommended, stopping oral bisphosphonates prior to dental surgery cannot be universally endorsed at this time, since it is unknown whether this is effective in reducing the risk of BRONJ (36).

Treatment of overt BRONJ

At present, there is no definite treatment for BRONJ. As it is delineated in Table I, patients with stages 1 and 2 of BRONJ should be treated using a conservative approach with the goal of preventing progression of lesions and limiting complications related to chronic infection. To achieve these goals, conservative debridement of bone sequestra, local irrigation with povidone-iodine and daily rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthwash, antibiotic therapy and pain control should be considered (9, 16-18). Surgical debridement has been variable effective in eradicating the necrotic bone. The goal of surgery should be to eliminate dead bone which acts as foreign material (34); thus necrotic areas, that are a constant source of soft tissue irritation, should be removed or recontoured without exposure of additional bone. In patients with BRONJ it may be difficult to obtain a surgical margin with viable bleeding bone as the jaw bones are metabolically damaged by the bisphosphonates; therefore aggressive surgical treatment should be delayed if possible (35). In cases of stage 3 patients with pathologic mandibular fractures segmental resection and reconstruction are required. However, because of the potential failure of this surgical procedure, the patient must be well informed of the carried risk. Also the immediate reconstruction with non vascularized or vascularized bone may carry the risk of failure as necrotic bone can develop at the surgical site (35). The efficacy of hyperbaric oxygen therapy remains uncertain. Some authors (5) have considered it as not effective and, therefore, did not recommended it; other authors (6), instead, have found hyperbaric oxygen therapy of some usefulness. A clinical trial is in progress in order to establish the efficacy of this treatment modality for patients with BRONJ (35).

Although it may seem reasonable and prudent to suggest that stopping the administration of iv bisphosphonates would improve the resolution rate of this condition, there is no proof to support such an indication for management. In fact there are evidences from the published studies that drug withdrawal does not lead to clinical improvement of BRONJ (16, 17). This can be well explained by the fact that bisphosphonates avidly bind to bone mineral around active osteoclasts, resulting in very high levels in the resorption lacunae. Because bisphosphonates are not metabolized, high concentrations are maintained within the bone for a long period of time. In cancer patients with overt BRONJ, the cessation or interruption of bisphosphonates must be discussed with the oncologist and always weighted against the risk of skeletal complications or hypercalcemia of malignancy (9, 16, 18).

Conclusion

BRONJ has been observed in several oral medicine, maxillofacial and oncology departments around the world. Although the definitive role of bisphosphonates remains to be elucidated, the alteration in bone metabolism together with surgical insult or prosthetic trauma appears to be key factors in the development of osteonecrosis. Tooth extraction as a precipitating event is a common observation in the reported literature. The reported incidence of BRONJ is significantly higher with the iv preparations zoledronic acid and pamidronate while the risk appears to be minimal for patients receiving oral bisphosphonates. The significant benefits that bisphosphonates offer to patients clearly outbalance the risk of potential side effects; however, any patient for whom prolonged bisphosphonate therapy is indicated, should be provided with preventive dental care in order to minimize the risk of developing this severe condition. Although discontinuation of iv bisphosphonates in cancer patients has been suggested, discontinuation of iv bisphosphonates prior to dental surgery cannot be universally accepted at this time, since it is unknown whether this is effective in reducing the risk of BRONJ (36).

References

- 1.Wang J, Goodger NM, Pogrel MA. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with cancer chemotherapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1104–1107. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00328-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenberg TJ, Ruggiero S. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:60. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.004. (letter) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marx RE. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;61:1115–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2391(03)00720-1. (letter) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Migliorati C.A. Bisphosphonates and oral cavity avascular bone necrosis. New Engl J Med. 2003;21:4253–4254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.99.132. (letter) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruggiero SL, Mehrotra B, Rosenberg TJ, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with the use of bisphosphonates: a review of 63 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62:527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lugassy G, Shaham R, Nemets A, et al. Severe osteomyelitis of the jaw in long-term survivors of multiple myeloma: a new clinical entity. Am J Med. 2004;117:440–441. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bagan JV, Murillo J, Poveda R, et al. Avascular jaw osteonecrosis in association with cancer chemotherapy: series of 10 cases. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:120–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vannucchi AM, Ficarra G, Antonioli E, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw associated with zoledronate therapy in a patient with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;128:738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05382.x. (letter) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ficarra G, Beninati F, Rubino I, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws in periodontal patients with a history of bisphosphonates treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1123–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Migliorati CA, Schubert MM, Peterson DE, et al. Bisphosphonateassociated osteonecrosis of mandibular and maxillary bone: an emerging oral complication of supportive cancer therapy. Cancer. 2005;104:83–93. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merigo E, Manfredi M, Meleti M, et al. Jaw bone necrosis without previous dental extractions associated with the use of bisphosphonates (pamidronate and zoledronate): a four- case report. J Oral Pathol Med. 2005;34:613–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olson KB, Hellie CM, Pienta KJ. Osteonecrosis of jaw in patient with hormone-refractory prostate cancer treated with zoledronic acid. Urology. 2005;66:658. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zervas K, Verrou E, Teleioudis Z, et al. Incidence, risk factors and management of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with multiple myeloma: a single-centre experience in 303 patients. Br J Haematol. 2006;134:620–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanna G, Preda L, Bruschini R, et al. Bisphosphonates and jaw osteonecrosis in patients with advanced breast cancer. Ann On-col. 2006;17:1512–1516. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Badros A, Weikel D, Salama Salama, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in multiple myeloma patients: clinical features and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:945–952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo S-B, Hellstein JW, Kalmar JR. Systematic review: bisphosphonates and osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:753–761. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-10-200605160-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migliorati CA, Siegel MA, Elting LS. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis: a long-term complication of bisphosphonates treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:508–514. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70726-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ruggiero SL, Fantasia J, Carlson E. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: background and guidelines for diagnosis, staging and management. Oral Sur Oral Pathol Oral Med. 2006;102:433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bilezikian JP. Osteonecrosis of the jaw-Do bisphosphonates pose a risk? N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2278–2281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunstan CR, Felsenberg D, Seibel MJ. Therapy insight: the risk and benefits of bisphosphonates for the treatment of tumor-induced bone disease. Nature Clin Pract Oncol. 2007;4:42–55. doi: 10.1038/ncponc0688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Body J-J, Coleman R, Clezardin P, et al. International society of geriatric oncology (SIOG) clinical practice recommendation for the use of bisphosphonates in elderly patients. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:852–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weitzman R, Sauter N, Eriksen EF, et al. Critical review: updated recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients-May 2006. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.12.005. (electronic version-in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dannemann C, Gratz KW, Riener, et al. Jaw osteonecrosis related to bisphosphonates therapy. A severe secondary disorder. Bone. 2007;40:828–834. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farrugia MC, Summerlin DJ, Krowiak E, et al. Osteonecrosis of the mandible or maxilla associated with the use of new generation bisphosphonates. Laringoscope. 2006;116:115–20. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000187398.51857.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brooks JK, Gilson AJ, Sindler AG, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaws associated with use of risendronate: report of 2 new cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2006.10.010. (electronic version-in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nase JB, Suzuki JB. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and oral bisphosphonates treatment. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137:1115–1119. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Senel FC, Tekin US, Durmus A, et al. Severe osteomyelitis of the mandible associated with the use of non-nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (disodium clodronate): report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:562–565. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miles AE. Phosphorus necrosis of the jaw: “phossy jaw”. Br Dent J. 1972;133:203–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4802906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellstein JW, Marek CL. Bisphosphonate osteochemonecrosis (bis-phossy jaw): is this phossy jaw of the 21st century? J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:682–9. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Silverman SL, Maricic M. Recent developments in bisphosphonates therapy. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2006.12.003. (electronic version-in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polizzotto MN, Cousins V, Schwarer AP. Bisphosphonate-associate osteonecrosis of the auditory canal. Br J Haematol. 2006;132:114. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barmias A, Kastritis E, Bamia C, et al. Ostenecrosis of the jaws in cancer after treatment bisphosphonates: incidence and risk factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8580–8587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lew DP, Waldvogel FA. Osteomyelitis. Lancet. 2004;364:269–279. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16727-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, et al. Bisphosphonates-induced exposed bone of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention, and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1567–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.No authors. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:369–376. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krueger CD, West PM, Sargent M, et al. Bisphosphonates-induced osteonecrosis of the jaws. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:276–284. doi: 10.1345/aph.1H521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]