Abstract

Obesity is an independent risk factor for developing chronic kidney disease. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), interleukin (IL)-18, and uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) are important components of the innate immune system mediating inflammatory renal damage. Early to midgestation maternal nutrient restriction appears to protect the kidney from the deleterious effects of early onset obesity, although the mechanisms remain unclear. We examined the combined effects of gestational maternal nutrient restriction during early fetal kidney development and early onset obesity on the renal innate immune response in offspring. Pregnant sheep were randomly assigned to a normal (control, 100%) or nutrient-restricted (NR, 50%) diet from days 30 to 80 gestation and 100% thereafter. Offspring were killed humanely at 7 days or, following rearing in an obesogenic environment, at 1 yr of age, and renal tissues were collected. IL-18 and TLR4 expression were strongly correlated irrespective of intervention. Seven-day NR offspring had significantly lower relative renal mass and IL-18 mRNA expression. At 1 yr of age, obesity resulted in increased mRNA abundance of TLR4, IL-18, and UCP2, coupled with tubular atrophy and greater immunohistological staining of glomerular IL-6 and medullary tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. NR obese offspring had a marked reduction of TLR4 abundance and renal IL-6 staining. In conclusion, maternal nutrient restriction during early fetal kidney development attenuates the effects of early onset obesity-related nephropathy, in part, through the downregulation of the innate inflammatory response. A better understanding of maternal nutrition and the in utero nutritional environment may offer therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing the burden of later kidney disease.

Keywords: interleukin-18, interleukin-6, Toll-like receptor 4, uncoupling protein 2, nephropathy, nutrition

obesity is a major worldwide public health concern, with up to 70% of obese adolescents remaining obese as adults (36). The rising prevalence of obesity has significant implications for health services dealing with the chronic diseases associated with the metabolic syndrome (36). As well as obesity, hypertension and diabetes are other components of the metabolic syndrome. The increasing prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) has mirrored that of obesity, and numerous studies have identified obesity as an independent risk factor for the development of CKD (5). Surprisingly, very little work has focused on the impact of early onset obesity, i.e., during childhood, on the development of CKD and the pathophysiology underlying it.

Recent work has demonstrated that the innate immune system is involved in the metabolic disturbances observed in obesity and diabetes (for reviews, see Refs. 9 and 16). Most notable components of this system include toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and interleukin (IL)-18, both thought to be important links between the innate immune and metabolic systems (9, 15). Although the main ligand for TLR4 is lipopolysaccharide, it can also be activated by nonesterified fatty acids (NEFA), which are elevated in obese individuals (16, 26). Plasma IL-18 levels are increased in obese individuals and those with diabetic nephropathy (2, 21). The precise function of uncoupling protein (UCP) 2 is still under intense investigation. However, there is now compelling evidence that it not only has an important protective role in reducing reactive oxygen species (ROS) (7) but that it is also plays a part in regulating the innate immune response (8, 29). With increasing inflammation and altered metabolic signaling, as occurs in obesity-related CKD, there is an increase in ROS (25). In the kidney, this may precipitate increased UCP2 abundance to potentially reduce the ROS generated within the renal cells and prevent further oxidative damage (7, 10). Activation of the innate immune system can induce additional inflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-6 (11, 21, 40), both of which have been shown to be involved in the inflammatory pathways associated with CKD (21, 27).

The developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis proposes that the in utero environment can influence the long-term health of the individual (35). This “programming” effect can increase the offspring's risk of developing obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. The in utero environment can also impact on kidney development with numerous models demonstrating that the early gestational period appears to be a critical window in which kidney structure can be altered, potentially influencing later renal function (20).

The sheep model of fetal renal development is well placed for investigating the in utero environment. Fetal renal development in sheep closely matches that of the human with nephrogenesis complete before birth (19, 32). We have previously demonstrated, in the sheep, that lean offspring previously exposed to a period of nutrient restriction from early to midgestation have a significant reduction in total nephron number at 6 mo of age compared with control animals (14). Similar findings have been reported by other groups (13). In addition, we have shown that adolescent-onset obesity results in marked renal inflammation, apoptosis, and glomerulosclerosis in young adults compared with lean control animals (37). Moreover, when maternal nutrient restriction, from early to midgestation, precedes the onset of obesity in offspring, we see a marked attenuation of these effects in young adults potentially conferring an element of renal protection from obesity-related nephropathy (37). These data demonstrate that a critical period of renal development occurs during early to midgestation, which could impact upon later renal function, although the mechanisms remain unclear.

To date, very little work has been undertaken to investigate the impact of early onset obesity on the development of obesity-related nephropathy and how this may be altered by exposure to suboptimal nutrition in utero. We hypothesized that the innate immune system could play an important role in the development of early onset obesity-related nephropathy and that these pathways could be altered by the in utero nutritional environment conferring some of the protection observed previously (37). Therefore, the present study aimed to: 1) establish the ontogeny of the key innate immune system proinflammatory genes TLR4, IL-18, and UCP2 in the kidney; 2) explore the effects of early onset obesity on these genes and the associated inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 in young adult kidneys; and 3) examine the combined effects of early to midgestational nutrient restriction followed by early onset obesity on these pathways in the renal tissues of young adult offspring.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and experimental design.

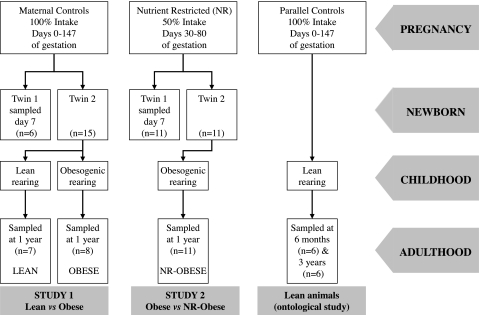

All procedures were performed with the necessary institutional ethical approval as designated under the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act, 1986. Twenty six twin-bearing ewes were randomly assigned to receive either their normal diet throughout pregnancy (100% of their metabolizable energy requirements of 7 MJ/day, n = 15) or to undergo a period of nutrient restriction (50% of their metabolizable energy requirements, n = 11) from early to midgestation (days 30 to 80 in the sheep) and fed their normal diet at all other times. To ensure correct nutritional intake was achieved throughout pregnancy, pregnant sheep were individually housed from the day of mating. Nutritional intakes were defined according to the standards stated by the Agricultural and Food Research Council (1). All mothers delivered spontaneously at term (∼147 days) and subsequently were fed a diet of ad libitum hay and a set amount of concentrate to meet their metabolizable and lactational energy requirements. All diets contained the required daily intake of minerals and vitamins. The gender of offspring was as follows: normal diet mothers 10 males, 12 females; nutrient-restricted (NR) mothers 6 males, 16 female. One twin from each mother was randomly assigned to be killed humanely at 7 days of age, and tissues were sampled. Remaining twins were reared naturally, as singletons, with their mother until their natural weaning period at ∼3 mo of age. After this, offspring were reared in one of the following two environments: pasture grazed, in keeping with “natural” rearing, allowing 17 animals/3,000 m2 and ad libitum access to grass and concentrate pellets (Lean, n = 7); or were reared in an adjacent open barn to promote early onset obesity with 17 animals/50 m2, reducing physical activity by 60% (37), with ad libitum access to hay and concentrate [Obese n = 8, NR-Obese (n = 11)]. This allowed two studies to be undertaken simultaneously, thereby reducing the number of animals needed and was in keeping with ethical guidance on research in animals (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/). The two studies were as follows: study 1, impact of early onset obesity on renal inflammation in young adults (groups: Lean and Obese); study 2, impact of prior early to midgestational nutrient restriction on renal inflammation in young adults following early onset obesity (groups: Obese and NR-Obese) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Experimental protocol from conception through to adulthood. Lean animals were utilized from a parallel study to investigate the ontological expression of the genes of interest. See materials and methods for further details.

To establish the early to midlife life ontogeny of the genes of interest, we utilized renal tissues from 12 further sheep aged 6 mo (2 males, 4 females) and 3 yr (6 males) comprising 8 twin and 4 singleton pregnancies. These animals were controls from a previous study, reared under similar conditions to the lean group described earlier, and allow a reduction in the number of animals used in keeping with ethical principles of animal research (http://www.nc3rs.org.uk/).

Animals remained in their study environments until 1 yr of age (young adults) when they were killed humanely by electrocortical stunning and exsanguination. Renal tissues were collected from all offspring at 7 days and 1 yr of age. Tissues were rapidly dissected and weighed before being sectioned and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage at −80°C until further analysis. Additional renal sections, for immunohistological analysis, were first fixed in 10% vol/vol formalin and then embedded in paraffin wax.

RNA extraction and reverse transcription.

Cortical renal tissue samples from all animals were analyzed for the mRNA abundance of the genes of interest. We extracted total RNA from 100 mg of renal tissue using Tri-reagent (Sigma, Poole, UK). Agarose gel electrophoresis (2%) and spectrophotometric analysis (Nanodrop; Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE) were used to verify both the RNA quality and quantity. For first-strand synthesis of cDNA, 1 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed (RT) using reverse transcriptase (Roche Diagnostics, Lewes, UK) and a Touchgene thermocycler (Techne; Barloworld Scientific, Stone, UK). Each 20-μl RT reaction consisted of 1 μg RNA, 1 μl hexanucleotide mix (10347631; Roche), 1 μl dNTPs (Roche), 1 μl buffer (Roche), 0.5 μl ribonuclease inhibitor, and 0.5 μl m-MuLV reverse transcriptase enzyme (Roche), and the total volume was made up with nuclease-free water (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK). To reduce the risk of contamination and genomic DNA carryover in each RT, we used deoxyribonuclease I (AMP-D1; Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. In addition, for each experiment, we included appropriate negative controls to exclude contaminating genomic DNA. All cDNA samples were stored at −20°C until further analysis.

Quantification of mRNA expression by real-time RT-PCR.

We used quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) to measure the mRNA abundance of TLR4, IL-18, and UCP-2. To ensure uniformity, efficiency, and accuracy of each 96-well plate, we generated a standard curve for each gene being analyzed. Following gel electrophoresis of the final product of PCR, DNA was extracted according to the manufacturer's instructions (QIAquick gel extraction kit 28704; Qiagen, Crawley, UK), and standard curves were generated. To ensure correct product validation, we confirmed the PCR product size on gel electrophoresis. For each gene, we performed qPCR using 20-μl reactions consisting of 1 μl of cDNA, 1× SYBR Green master mix (Qiagen) and 500 nM forward and reverse ovine-specific oligonucleotide primers (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) for TLR4, IL-18, and UCP2 as previously described (33). Reverse (R) and forward (F) primer sequences were as follows: TLR4 F-TGCTGGCTGAAAAATATG, R-CCCTGTAGTGAAGGCAGAGC; IL-18 F-ACGACCAAGTTCTCTTCATTAGC, R-GAACAGTCAGAATCAGGCATATCC; and UCP2 F-ATGACAGACGACCTCCCTTG, R-GGGCATGAACCCTTTGTAGA. Samples were run in duplicate and included appropriate negative controls. qPCR was performed in 96-well plates using the Techne Quantica 14 real-time thermocycler (Techne; Barloworld Scientific) for 40 cycles. Experiments were excluded and repeated if any of the following occurred: standard curve analysis demonstrated an r2 < 0.985; the efficiency was beyond 2 ± 0.05; or negative controls were positive within the standard curve. 18S rRNA was used as a housekeeping gene to normalize the mRNA expression (33). qPCR data were analyzed using the 2−ΔCT method (18) and expressed as a ratio to the 1-yr-old lean animals.

Immunohistochemistry.

Paraffin-embedded renal tissue sections of 1-yr-old offspring were cut at 5 μm and mounted overnight on Superfrost plus glass microscope slides (Menzel-Glaser, Braunschweig, Germany). They were then dewaxed in Xylene before stepwise rehydration in alcohol. Immunohistological staining was then performed on the Bond-max histology system using Bond Polymer Refine Detection System (DS9800 and Bond software v3.4A; Vision Biosystems, Mount Waverley, Australia). All animal slides, for each antibody, were run at the same time, under the same conditions, and in the same batch to ensure uniformity of staining using the automated protocol. Slides were heated and stained according to the following protocol: 5 min peroxide block, 15 min primary antibody, 8 min secondary antibody, 10 min 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB), and 5 min counterstaining with hematoxylin and eosin. Appropriate negative slides, for each antibody, were run in parallel with the exclusion of the primary antibody. The primary antibodies, and their concentrations, used were as follows: TNF-α at 1:400 (MCA2334 AbD; Serotec, Kidlington, UK) and IL-6 at 1:400 (ab6672; Abcam plc, Cambridge, UK). Slides were then imaged using a Nikon Eclipse 90i microscope with a charge-coupled device high-speed color camera (Micropublisher 3.3RTV; Qimaging, Surrey, BC, Canada) and analyzed in an unbiased, blinded fashion using Volocity 4 quantification software (v4.2.1; Improvision, Coventry, UK). The quantification software corrected any variation in background staining as previously validated (32).

Assessment of tubular atrophy.

To assess the degree of tubular atrophy, we examined the renal cortex sections histologically using light microscopy of hematoxylin- and eosin-stained sections, as previously described (12, 34). Briefly, tubules were assessed from two randomly selected fields (×20 magnification) per animal (n = 7/group), with each section having >150 tubules. Tubular atrophy within the interstitium was graded in a blinded fashion using the Banff 97 semiquantitative score (24) as follows: 0 (no tubular atrophy), 1 (<25% atrophic tubules), 2 (26–50% atrophic tubules), and 3 (>50% atrophic tubules).

Statistical analysis.

To assess the data for normality, we performed a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test followed by the appropriate parametric or nonparametric analysis. Data were analyzed using ANOVA with post hoc Bonferronni correction for multiple tests, independent Student's t-test, or Mann-Whitney test as appropriate. Tubule atrophy scores were not normally distributed and so were analyzed using Mann-Whitney. The effects of the prenatal and postnatal diet in young adults were tested a priori as Lean vs. Obese and Obese vs. NR-Obese. Correlations were determined by the Spearman rank-order test. All data were analyzed using SPSS software (v15.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL) and expressed as means ± SE with significance set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Renal ontogeny of TLR4, IL-18, and UCP2.

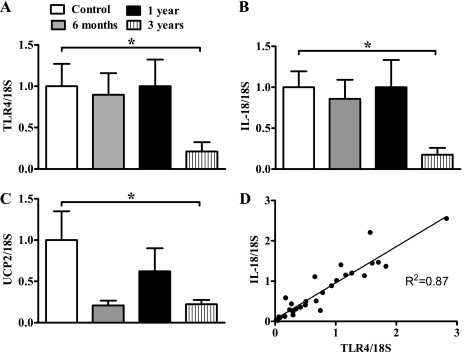

We explored the ontological expression of TLR4, IL-18, and UCP2 in renal tissue to better understand the impact of obesity and nutrient restriction on these genes. TLR4 and IL-18 expression was significantly higher in the newborn period than in midlife (3 yr old) (Fig. 2, A and B). UCP2 expression was also at its greatest during early life, with a marked reduction at 3 yr of life (Fig. 2C). Interestingly, there was a strong correlation between TLR4 and IL-18 throughout this early to midlife time period (r2 = 0.87, P < 0.0001). No such correlations were observed with UCP2 (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

The ontological development of renal tissue gene expression for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4; A), interleukin (IL)-18 (B), and uncoupling protein (UCP) 2 mRNA (C) from neonatal to adult life. D: positive correlation between renal TLR4 and IL-18 mRNA in lean animals from all ages (r2 = 0.87, P < 0.0001) (n = 26). mRNA abundance determined by real-time PCR and expressed as a degree of change to the 7-day-old animals (control); n = 5–8 control animals/time point, and values are expressed as means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

Growth and metabolic status.

Growth and metabolic data for the offspring at 7 days of age and 1 yr of age have recently been reported by our group (30, 37) and are summarized below along with new data (7-day-old animal renal mass and relative renal mass).

7-Day-old animals.

There were no differences between 7-day-old control and NR animals in terms of their birth weight, weight at 7 days, or fat mass (30). However, although total kidney weight was not different between the groups (control 30.1 ± 1.2 vs. NR 27.3 ± 1.5 g), relative kidney weight (kidney mass-to-body mass ratio) was significantly lower in the NR group (control 6.9 ± 0.4 vs. NR 5.8 ± 0.2 g/kg, P < 0.01).

1-Year-old animals.

The obesogenic environment resulted in a 65% reduction in physical activity compared with the lean animals reared in their natural environment (30). Obese animals had a significantly greater body mass (Lean 58 ± 4 kg vs. Obese 91 ± 2 kg vs. NR-Obese 89 ± 2 kg) (30) and kidney mass (Lean 117 ± 9 g vs. Obese 155 ± 7 g vs. NR-Obese 164 ± 7 kg) but not relative kidney mass (Lean 2 ± 0.1 g/kg vs. Obese 1.7 ± 0.1 g/kg vs. NR-Obese 1.9 ± 0.1 g/kg) (37). Metabolically, obesity resulted in a twofold increase in plasma NEFA, a 2.4-fold increase in plasma insulin, but no significant increase in fasting plasma glucose (30).

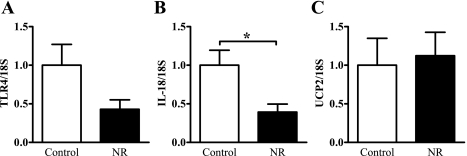

Impact of nutrient restriction on gene expression at 7 days old.

At 7 days of age, the renal expression of TLR4 was 57% lower in the NR animals compared with the controls, but this did not reach significance (P = 0.11, Fig. 3A). However, there was a 60% reduction in IL-18 in the NR animals (P < 0.05, Fig. 3B). UCP2 expression was similar between the controls and NR animals at this age (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

mRNA abundance of TLR4 (A), IL-18 (B), and UCP2 (C) in renal tissue of 7-day-old control and nutrient-restricted (NR) offspring as determined by quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR). Data are expressed relative to the housekeeping gene 18S and normalized to the control group to give the degree of change; n = 5–7 animals/group. Data represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

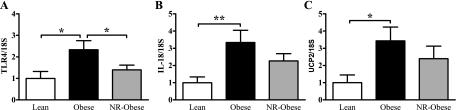

Effect of early onset obesity and nutrient restriction on young adult offspring renal gene abundance.

In young adults, following early onset obesity, we saw a marked activation of the renal innate immune system-related genes. There were significant increases in the abundance of TLR4 (2-fold, P < 0.05), IL-18 (3-fold, P < 0.01), and UCP2 (3.5-fold, P < 0.05) genes in Obese compared with Lean animals (Fig. 4). When early onset obesity was induced in offspring previously NR in utero (NR-Obese), we observed a significant reduction in TLR4 gene expression (1.7-fold, P < 0.05) compared with Obese controls but no significant differences in IL-18 or UCP2 gene expression (Fig. 4). The strong positive correlation between IL-18 and TLR4, observed with lean animals, persisted when combining all animal groups (r2 = 0.76, P < 0.0001).

Fig. 4.

mRNA abundance of TLR4 (A), IL-18 (B), and UCP2 (C) in renal tissue of 1-yr-old Lean, Obese, and NR-Obese offspring as determined by qPCR. Data are expressed relative to the housekeeping gene 18S and normalized to the Lean group to give the degree of change; n = 7–10 animals/group. Data represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

Effect of early onset obesity and nutrient restriction on renal cytokines in young adult offspring.

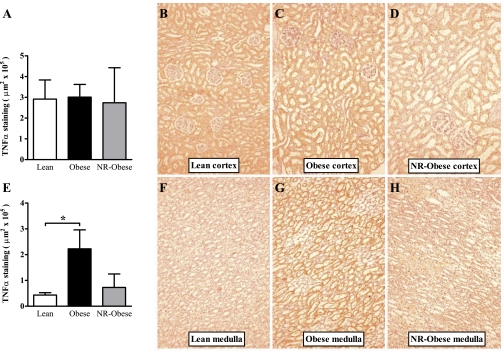

We next explored the renal tissue distribution of TNF-α and IL-6, using immunohistochemistry, in young adults to ascertain the effect of obesity on renal inflammation and how this might be altered by the in utero environment. Interestingly, following staining, it became apparent that the tissue distributions for both cytokines varied dramatically in keeping with apoptotic differences noted previously in the cortex and medulla (37). TNF-α distribution was markedly different between the cortex and medulla regions of the kidney. IL-6 was quantified in both in the glomerular and nonglomerular renal tissue, since previous studies had highlighted a greater abundance predominantly within the glomerular structures (12, 34). For TNF-α, we observed no differences between Lean and Obese animals in the renal cortex. However, there was a significant increase in the renal medulla of Obese animals (5-fold, P = 0.01, Fig. 5). In study 2, there were again no significant differences between Obese and NR-Obese animals in the quantity of TNF-α in the medulla or the cortex. However, although there was a threefold reduction of TNF-α in the medulla of the NR-Obese compared with Obese offspring, this did not reach significance (P = 0.11, Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Quantitative immunohistochemistry of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α in renal tissue of young adult offspring. TNF-α stained with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, red-brown color) as described in materials and methods. Renal cortex (A) and medulla (E) quantification and representative micrographs (×20) of Lean (B and F), Obese (C and G), and NR-Obese (D and H) offspring. Data represent means ± SE; n = 5–7 animals/group. *P < 0.05.

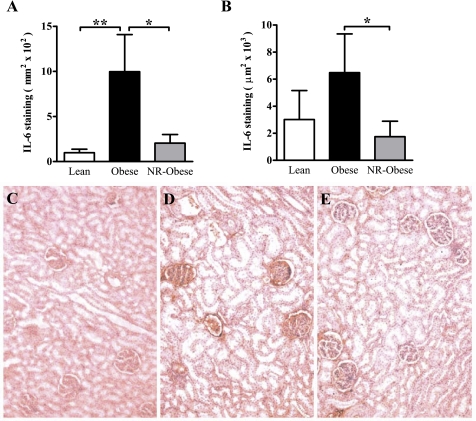

Immunohistochemistry of IL-6 revealed differences in both glomerular and nonglomerular staining. In study 1, Obese animals had a significant increase in the quantity of IL-6 within the glomerular structure (10-fold increase, P < 0.01, Fig. 6A) but no difference in the nonglomerular staining (Fig. 6B) compared with Lean animals. In study 2, NR-Obese compared with Obese animals had a significant reduction in IL-6 staining within the glomerular (5-fold decrease, P < 0.05, Fig. 6A) and nonglomerular (3.7-fold decrease, P < 0.05, Fig. 6B) tissue.

Fig. 6.

Quantitative immunohistochemistry of IL-6 in renal cortical tissue of young adult offspring. IL-6 stained with DAB (red-brown color) as described in materials and methods. A: cortical glomerular quantification. B: total cortical staining excluding glomeruli. Representative micrographs (×20) of Lean (C), Obese (D), and NR-Obese (E) offspring. Data represent means ± SE; n = 5–6 animals/group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01.

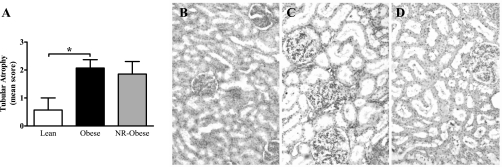

Tubular atrophy in young adult offspring.

IL-6 in diseased human kidneys correlates with tubular atrophy (12, 34). Examination of young adult kidneys demonstrated tubular atrophy in Obese animals compared with Lean (P < 0.05) but no differences between Obese and NR-Obese (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Semiquantitative measurement of tubular atrophy (A) as described in materials and methods. Tubular atrophy was scored as: 0 (no tubular atrophy), 1 (<25% atrophic tubules), 2 (25–50% atrophic tubules), and 3 (>50% atrophic tubules). Representative micrographs (×40) of Lean (B), Obese (C), and NR-Obese (D) offspring demonstrating marked dilated and atrophic tubules in the renal cortex of Obese and NR-Obese animals. Data represent means ± SE; n = 7 animals/group. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

These are the first data that not only highlight the importance of the innate immune system in the development of obesity-related nephropathy but also demonstrate that its response to this challenge can be programmed by the in utero nutritional environment, perhaps conferring an element of apparent renal protection.

It is surprising that, with the rising prevalence of obesity-related CKD, little research has focused on the mechanisms involved. The strength of our model is that the development of obesity resembles that currently observed in contemporary western society, i.e., increased food intake and reduced physical activity. In addition, renal development in the sheep, unlike the rodent, closely follows that of the human (19), allowing prenatal events, such as nutritional interventions, to be better studied.

To understand the renal gene expression patterns, and the effects of nutritional interventions, we examined the early to midlife ontological development of key innate system genes. For TLR4, IL-18, and UCP2, we demonstrate a marked reduction in their abundance in older animals (approaching middle age equivalent in humans), which, for TLR4 and IL-18, is in keeping with that seen in adipose tissue (33). This may suggest that early life is a sensitive period when the expression of these genes can be influenced. It may also reflect the impaired function of the innate immune response observed with aging (4, 17). The significant correlation between TLR4 and IL-18 gene abundance highlights the importance of their common intracellular signaling pathways (31) and could potentially suggest a crucial interplay between them during the renal innate immune response.

In study 1, we investigated the impact of early onset obesity on the innate immune response in young adult kidneys. The marked upregulation of TLR4 and IL-18 gene expression in Obese young adults is in keeping with the increased inflammation and glomerulosclerosis observed in these animals (37). The relative contribution of these genes to this inflammatory damage cannot be ascertained from this study, although they are likely to be an important component, since these animals have significantly higher plasma NEFA, which could act as a ligand promoting a proinflammatory state in the renal tissue. In acute renal injury models, both IL-18 and TLR4 play crucial roles in the inflammatory damage. Indeed, mouse knockout models of IL-18 or TLR4 are protected from the renal damage caused by acute ischemia-reperfusion injury (38, 39). The increased UCP2 abundance could also reflect activation of the innate immune response and a compensatory response to elevated ROS. The elevated plasma insulin levels observed in the Obese animals may suggest they are entering the early stages of insulin resistance, and hence the raised renal UCP2 expression could be indicative of an evolving diabetic nephropathy (10). Histologically, in Obese young adults, there is evidence of tubular atrophy, increased glomerular IL-6 and medullary TNF-α. The tubular atrophy and glomerulosclerosis (37) are in keeping with that observed in other obese models (28) and may represent the hyperfiltration phase of obesity-related nephropathy. With obesity, there is increased localization of IL-6 in the glomeruli but no difference in nonglomerular staining. Glomerular localization has previously been reported in human diabetic nephropathy (12, 34) and may partly explain the increased glomerulosclerosis observed in our model. The increased TNF-α staining in the medulla, possibly stimulated by elevated TLR4 or IL-18, parallels the increased apoptosis seen in Obese animals (37) and could, therefore, be an important part of the renal tissue inflammation that accompanies obesity-related nephropathy.

Study 2 explored the combined effects of early to midgestational nutrient restriction and subsequent early onset obesity in the renal tissues of young adult offspring. In our model, it is important to note that the birth weights of control and NR offspring were not different despite the moderate amount of maternal nutrient restriction. However, at 7 days of age, NR offspring had a significantly lower relative kidney weight and IL-18 abundance compared with controls. Both UCP2 and TLR4 were not different between the groups at this age, although the latter shows a trend to lower abundance. The downregulation of IL-18 in the early newborn period may offer a degree of renal protection when subsequently challenged with early onset obesity. This is apparent in young adults where we observe a downregulation of TLR4 abundance and IL-6 content in the NR-Obese group. Obese and NR-Obese animals have similar raised plasma levels of NEFA (compared with the lean animals) that could result in activation of the TLR4 proinflammatory pathway. TLR4 is significantly lower in the NR-Obese animals; therefore, activation of inflammatory pathways via TLR4, such as IL-6 and TNF-α, could be diminished and could partly explain their apparent molecular and histological protection. IL-6 and TNF-α have been implicated in the progression of glomerulosclerosis in diabetic nephropathy acting on the extracellular matrix of mesangial cells and podocytes (6, 21).

Although IL-18 is downregulated at 7 days of age in the NR group, this does not persist in the young adult NR-Obese animals. One possible explanation is that the challenge of early onset obesity has overwhelmed this pathway, masking any differences, but it is not clear from our study at what stage this could have occurred. Indeed, it may have occurred late on and, therefore, delayed the onset of renal inflammation and subsequent glomerulosclerosis (37). Clearly, further work is needed to establish the ontological development of these findings as well as extending the study into older animals to see if the histological and molecular protection impact on later renal function. Nonetheless, the strong relationship between IL-18 and TLR4 persists irrespective of nutritional group or later-onset obesity. This supports the hypothesis that these two important genes are closely linked and could explain why IL-18 or TLR4 knockout models both respond in a similar way when challenged with an acute renal insult (23, 38, 39). It is not possible to establish from this study which, if any, is the more dominant, although it has been suggested that TLR4 initiates and mediates the renal damage associated with activation of the innate immune response (23).

We have been unable to reproducibly establish total nephron numbers in obese animals because of the marked renal hypertrophy that occurs with obesity. However, using the same model, our group and others have previously shown that lean adolescent NR offspring have significantly fewer nephrons (13, 14). Because nephrogensis is complete before birth, it is surprising that a period of modest maternal undernutrition during the “critical window” of kidney development in the fetal sheep (early to midgestation) can differentially alter both the structure (negatively) and inflammatory profile (positively) in the offspring. This may partly explain why a reduced nephron number does not necessarily result in hypertension (3), although Gilbert and colleagues (13), using the same model, have found an association between nephron number and blood pressure. Their study, using the same model of nutrient restriction, appears to demonstrate a critical point at which reduced nephron number is associated with hypertension in lean animals (13). Although an interesting observation, both their work and the present study highlight the need for a definitive study controlling for gender, parity, and fetal number, since it is unlikely that nephron number alone is responsible for the hypertension. Both groups of obese young adults are equally hypertensive in our model, suggesting it is obesity per se that results in the hypertension despite the significant differences in renal tissue damage observed (37). Despite the differences noted here between Obese and NR-Obese animals at a histological and molecular level, in addition to the possible nephron number differences, blood pressure and renal function remain similar between the groups with a tendency toward hyperfiltration (37). This could possibly reflect a similar number of functioning nephrons with the Obese group losing nephrons via glomerulosclerosis and the NR-Obese entering life with a reduced nephron number subsequently protected from further loss via a downregulation of the innate inflammatory response. However, renal downregulation of the innate immune system observed in the NR-Obese animals may not persist into later life and may, in fact, result in this group failing to respond appropriately to infection, potentially resulting in significant renal damage (22). The evolution of these changes in later life warrants further investigation.

The novel data presented in this study offer new insights into the inflammatory mechanisms of obesity-related nephropathy and the impact of maternal nutrition on these pathways, although our study does have some limitations. To date, we have been unable to identify suitable antibodies for IL-18 and TLR4 for use in our model. As such, the mRNA data presented requires additional work to validate correlation of the message signal with protein quantity as observed in other kidney models (38, 39). One additional limitation is the absence of a lean NR group. The focus of the present study was on the impact of obesity, and we have previously studied lean NR animals into early adolescence (14). Additional studies are required to examine the impact of this period of nutrient restriction, in lean and obese sheep, into mid and late life, allowing further renal evaluation with increasing age.

In conclusion, early onset obesity results in activation of the renal innate immune system, contributing to the development of obesity-related nephropathy in young adults. Importantly, this response is significantly reduced in offspring previously exposed to a period of maternal gestational nutrient restriction during early fetal kidney development. This may, in part, explain the reduction in cellular stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and glomerulosclerosis observed in this model (32, 37). Although, following early onset obesity, this may confer an element of renal protection, it could also be disadvantageous by limiting the immune response to infection (22). A better understanding of the mechanisms leading to obesity-related nephropathy, and how this can be influenced by the in utero environment, may offer new therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing the burden of cardiovascular and kidney disease in the face of the current obesity epidemic.

GRANTS

This work was support by a British Heart Foundation Clinical Fellowship (D. Sharkey, FS/05/098/19942) and Lectureship (D. S. Gardner, BS/03/01) and the European Union Sixth Framework for Research and Technical Development of the European Community-The Early Nutrition Programming Project (FOOD-CT-2005-007036).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Vicky Wilson for assistance preparing the tissue blocks for histology.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderman G. AFRC Technical Committee on Responses to Nutrients. Energy and protein requirements of ruminants Wallingford, UK: CAB International, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Araki S, Haneda M, Koya D, Sugimoto T, Isshiki K, Chin-Kanasaki M, Uzu T, Kashiwagi A. Predictive impact of elevated serum level of IL-18 for early renal dysfunction in type 2 diabetes: an observational follow-up study. Diabetologia 50: 867–873, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennan KA, Kaufman S, Reynolds SW, McCook BT, Kan G, Christiaens I, Symonds ME, Olson DM. Differential effects of maternal nutrient restriction through pregnancy on kidney development and later blood pressure control in the resulting offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295: R197–R205, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chelvarajan RL, Liu Y, Popa D, Getchell ML, Getchell TV, Stromberg AJ, Bondada S. Molecular basis of age-associated cytokine dysregulation in LPS-stimulated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 79: 1314–1327, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chertow GM, Hsu CY, Johansen KL. The enlarging body of evidence: obesity and chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1501–1502, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalla Vestra M, Mussap M, Gallina P, Bruseghin M, Cernigoi AM, Saller A, Plebani M, Fioretto P. Acute-phase markers of inflammation and glomerular structure in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: Suppl 1: S78–S82, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Echtay KS, Roussel D, St-Pierre J, Jekabsons MB, Cadenas S, Stuart JA, Harper JA, Roebuck SJ, Morrison A, Pickering S, Clapham JC, Brand MD. Superoxide activates mitochondrial uncoupling proteins. Nature 415: 96–99, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emre Y, Hurtaud C, Karaca M, Nubel T, Zavala F, Ricquier D. Role of uncoupling protein UCP2 in cell-mediated immunity: how macrophage-mediated insulitis is accelerated in a model of autoimmune diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 19085–19090, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandez-Real JM, Pickup JC. Innate immunity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab 19: 10–16, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friederich M, Fasching A, Hansell P, Nordquist L, Palm F. Diabetes-induced up-regulation of uncoupling protein-2 results in increased mitochondrial uncoupling in kidney proximal tubular cells. Biochim Biophys Acta 1777: 935–940, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu Y, Xie C, Chen J, Zhu J, Zhou H, Thomas J, Zhou XJ, Mohan C. Innate stimuli accentuate end-organ damage by nephrotoxic antibodies via Fc receptor and TLR stimulation and IL-1/TNF-alpha production. J Immunol 176: 632–639, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukatsu A, Matsuo S, Tamai H, Sakamoto N, Matsuda T, Hirano T. Distribution of interleukin-6 in normal and diseased human kidney. Lab Invest 65: 61–66, 1991 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert JS, Lang AL, Grant AR, Nijland MJ. Maternal nutrient restriction in sheep: hypertension and decreased nephron number in offspring at 9 months of age. J Physiol 565: 137–147, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gopalakrishnan GS, Gardner DS, Dandrea J, Langley-Evans SC, Pearce S, Kurlak LO, Walker RM, Seetho IW, Keisler DH, Ramsay MM, Stephenson T, Symonds ME. Influence of maternal pre-pregnancy body composition and diet during early-mid pregnancy on cardiovascular function and nephron number in juvenile sheep. Br J Nutr 94: 938–947, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hung J, McQuillan BM, Chapman CM, Thompson PL, Beilby JP. Elevated interleukin-18 levels are associated with the metabolic syndrome independent of obesity and insulin resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1268–1273, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy A, Martinez K, Chuang CC, LaPoint K, McIntosh M. Saturated fatty acid-mediated inflammation and insulin resistance in adipose tissue: mechanisms of action and implications. J Nutr 139: 1–4, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Larbi A, Franceschi C, Mazzatti D, Solana R, Wikby A, Pawelec G. Aging of the immune system as a prognostic factor for human longevity. Physiology (Bethesda) 23: 64–74, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moritz KM, Dodic M, Wintour EM. Kidney development and the fetal programming of adult disease. Bioessays 25: 212–220, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moritz KM, Singh RR, Probyn ME, Denton KM. Developmental programming of a reduced nephron endowment: more than just a baby's birth weight. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F1–F9, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Navarro-Gonzalez JF, Mora-Fernandez C. The role of inflammatory cytokines in diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 433–442, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patole PS, Schubert S, Hildinger K, Khandoga S, Khandoga A, Segerer S, Henger A, Kretzler M, Werner M, Krombach F, Schlondorff D, Anders HJ. Toll-like receptor-4: renal cells and bone marrow cells signal for neutrophil recruitment during pyelonephritis. Kidney Int 68: 2582–2587, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pulskens WP, Teske GJ, Butter LM, Roelofs JJ, van der Poll T, Florquin S, Leemans JC. Toll-like receptor-4 coordinates the innate immune response of the kidney to renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. PLoS ONE 3: e3596, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Racusen LC, Solez K, Colvin RB, Bonsib SM, Castro MC, Cavallo T, Croker BP, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Fogo AB, Furness P, Gaber LW, Gibson IW, Glotz D, Goldberg JC, Grande J, Halloran PF, Hansen HE, Hartley B, Hayry PJ, Hill CM, Hoffman EO, Hunsicker LG, Lindblad AS, Yamaguchi Y. The Banff 97 working classification of renal allograft pathology. Kidney Int 55: 713–723, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramos LF, Shintani A, Ikizler TA, Himmelfarb J. Oxidative stress and inflammation are associated with adiposity in moderate to severe CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 593–599, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reyna SM, Ghosh S, Tantiwong P, Meka CS, Eagan P, Jenkinson CP, Cersosimo E, Defronzo RA, Coletta DK, Sriwijitkamol A, Musi N. Elevated toll-like receptor 4 expression and signaling in muscle from insulin-resistant subjects. Diabetes 57: 2595–2602, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivero A, Mora C, Muros M, Garcia J, Herrera H, Navarro-Gonzalez JF. Pathogenic perspectives for the role of inflammation in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 116: 479–492, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Quiroz Y, Shahkarami A, Li Z, Vaziri ND. Mycophenolate mofetil ameliorates nephropathy in the obese Zucker rat. Kidney Int 68: 1041–1047, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rousset S, Emre Y, Join-Lambert O, Hurtaud C, Ricquier D, Cassard-Doulcier AM. The uncoupling protein 2 modulates the cytokine balance in innate immunity. Cytokine 35: 135–142, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sebert SP, Hyatt MA, Chan LL, Patel N, Bell RC, Keisler D, Stephenson T, Budge H, Symonds ME, Gardner DS. Maternal nutrient restriction between early and midgestation and its impact upon appetite regulation after juvenile obesity. Endocrinology 150: 634–641, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seki E, Tsutsui H, Nakano H, Tsuji N, Hoshino K, Adachi O, Adachi K, Futatsugi S, Kuida K, Takeuchi O, Okamura H, Fujimoto J, Akira S, Nakanishi K. Lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-18 secretion from murine Kupffer cells independently of myeloid differentiation factor 88 that is critically involved in induction of production of IL-12 and IL-1beta. J Immunol 166: 2651–2657, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sharkey D, Gardner DS, Fainberg HP, Sebert S, Bos P, Wilson V, Bell R, Symonds ME, Budge H. Maternal nutrient restriction during pregnancy differentially alters the unfolded protein response in adipose and renal tissue of obese juvenile offspring. Faseb J 23: 1314–1324, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sharkey D, Symonds ME, Budge H. Adipose tissue inflammation: developmental ontogeny and consequences of gestational nutrient restriction in offspring. Endocrinology 150: 3913–3920, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki D, Miyazaki M, Naka R, Koji T, Yagame M, Jinde K, Endoh M, Nomoto Y, Sakai H. In situ hybridization of interleukin 6 in diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 44: 1233–1238, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Symonds ME. Integration of physiological and molecular mechanisms of the developmental origins of adult disease: new concepts and insights. Proc Nutr Soc 66: 442–450, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viner RM, Cole TJ. Who changes body mass between adolescence and adulthood? Factors predicting change in BMI between 16 year and 30 years in the 1970 British Birth Cohort. Int J Obes (Lond) 30: 1368–1374, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams PJ, Kurlak LO, Perkins AC, Budge H, Stephenson T, Keisler D, Symonds ME, Gardner DS. Hypertension and impaired renal function accompany juvenile obesity: the effect of prenatal diet. Kidney Int 72: 279–289, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu H, Chen G, Wyburn KR, Yin J, Bertolino P, Eris JM, Alexander SI, Sharland AF, Chadban SJ. TLR4 activation mediates kidney ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest 117: 2847–2859, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu H, Craft ML, Wang P, Wyburn KR, Chen G, Ma J, Hambly B, Chadban SJ. IL-18 contributes to renal damage after ischemia-reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2331–2341, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang B, Ramesh G, Uematsu S, Akira S, Reeves WB. TLR4 signaling mediates inflammation and tissue injury in nephrotoxicity. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 923–932, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]