Abstract

Hyperphosphatemia associated with chronic kidney disease is one of the factors that can promote vascular calcification, and intestinal Pi absorption is one of the pharmacological targets that prevents it. The type II Na-Pi cotransporter NaPi-2b is the major transporter that mediates Pi reabsorption in the intestine. The potential role and regulation of other Na-Pi transporters remain unknown. We have identified expression of the type III Na-Pi cotransporter PiT-1 in the apical membrane of enterocytes. Na-Pi transport activity and NaPi-2b and PiT-1 proteins are mostly expressed in the duodenum and jejunum of rat small intestine; their expression is negligible in the ileum. In response to a chronic low-Pi diet, there is an adaptive response restricted to the jejunum, with increased brush border membrane (BBM) Na-Pi transport activity and NaPi-2b, but not PiT-1, protein and mRNA abundance. However, in rats acutely switched from a low- to a high-Pi diet, there is an increase in BBM Na-Pi transport activity in the duodenum that is associated with an increase in BBM NaPi-2b protein abundance. Acute adaptive upregulation is restricted to the duodenum and induces an increase in serum Pi that produces a transient postprandial hyperphosphatemia. Our study, therefore, indicates that Na-Pi transport activity and NaPi-2b protein expression are differentially regulated in the duodenum vs. the jejunum and that postprandial upregulation of NaPi-2b could be a potential target for treatment of hyperphosphatemia.

Keywords: SLC34A2, PiT-1, hyperphosphatemia, chronic kidney disease, dietary Pi

in the past several years, numerous studies have related hyperphosphatemia with progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD), increased vascular stiffness, vascular calcification, and increased cardiovascular morbidity (1, 4, 21, 26). End-stage renal disease patients undergoing dialysis show particularly increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. In an attempt to control serum phosphate levels, emerging treatments have focused on reducing Pi availability in the intestinal lumen by dietary restriction or by use of Pi binders (7–9). The effects and success of these measures are limited in part because of compliance issues and the side effect profile of Pi binders (6, 17). Although it would be desirable to identify specific inhibitors of intestinal Pi transport allowing specific modulation of Pi absorption, not much is known about the physiological regulation of Pi absorption in the small intestine and how metabolic conditions can affect the fine tuning of the regulation between intestinal Pi absorption and renal Pi reabsorption.

Low dietary Pi intake (11, 14), vitamin D (19), and estrogens (32) increase intestinal Pi reabsorption, whereas fibroblast growth factor-23 (22) and glucocorticoids (2) decrease intestinal Pi reabsorption. Dietary Pi intake and vitamin D are the most important regulators of Pi absorption in the intestine. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25-(OH)2D3], the active form of vitamin D, activates vitamin D receptor (VDR), inducing transcriptional upregulation of NaPi-2b in the small intestine. Chronic low-Pi diets induce an increase in serum 1,25-(OH)2D3 by activation of 1α-hydroxylase in the kidney. This effect suggests that intestinal adaptation to a chronic low-Pi diet is mediated by vitamin D. However, low-Pi diet-induced upregulation of NaPi-2b is independent of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and VDR, since adaptation to a low-Pi diet is intact in VDR- and 1α-hydroxylase-deficient mice (5).

In the present study, we have characterized the protein expression profile of NaPi-2b in the rat small intestine. Moreover, we have identified expression of the type III transporter PiT-1 in the apical membrane of the enterocytes. We have also studied the adaptation of these Na-Pi transporters to chronic and acute changes in dietary Pi. Our findings suggest that the duodenum and jejunum can play different roles in the adaptation to chronic vs. acute alterations of dietary Pi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and diets.

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (8–10 wk old, 200–250 g body wt; Harlan, Madison, WI) were fed diets with different concentrations of phosphate: low (0.1%) Pi (diet TD.85010, Teklad, Madison, WI), normal (0.6%) Pi (diet TD.84122, Teklad), and high (1.2%) Pi (diet TD.85349, Teklad). The diets were otherwise matched for their calcium, magnesium, sodium, protein, fat, and vitamin D content. In the chronic adaptation studies, the rats were fed the different Pi diets ad libitum for 7 days. In the acute adaptation studies, the rats were fed the 0.1% Pi diet for 4 h in the morning for 7 consecutive days. On the day of the experiment, the rats were fed the 0.1% or 1.2% Pi diet for 4 h before the experiments. Normal drinking water was supplied ad libitum. We studied 18 rats in each experimental group.

The animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Colorado Denver.

Materials.

All chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO) except when noted. The polyclonal rabbit anti-NaPi-2b antibody was custom generated by Davids Biotechnologie (Regensburg, Germany) by injection of the peptide CKNLEEEEKEQDVPVKAS (amino acids 644–661) located at the COOH terminus of the rat protein. Peptide conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin was injected into two different rabbits. The affinity-purified antibody was used at 1:1,000 dilution for Western blotting and at 1:100 dilution for immunofluorescence. The rabbit anti-PiT-1 antibody was produced by Davids Biotechnologie using a method similar to that described for polyclonal rabbit anti-NaPi-2b antibody, but with use of the peptide SLVAKGQEGIKWSELIK. Polyclonal rabbit PiT-1 antibody was used at 1:1,000 dilution for Western blotting. Another polyclonal chicken PiT-1 antibody raised against the same peptide was used successfully at 1:50 dilution for immunofluorescence. Specificity of all the antibodies was tested by blocking the signal with the corresponding antigenic peptide for Western blotting (see supplemental Fig. 1 in the online version of this article) and immunofluorescence microscopy.

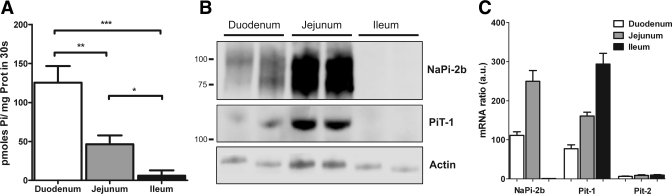

Fig. 1.

Expression profile of Na-Pi transporter activity, protein, and mRNA along the small intestine of rats (n = 6) fed the 0.6% Pi diet ad libitum. A: brush border membrane (BBM) vesicle (BBMV) Na-dependent Pi uptake activity in small intestinal segments. B: BBMV expression of NaPi-2b and PiT-1 protein showing specific signal in duodenum and jejunum, but not ileum, of rats; 20 μg of protein were loaded per well. C: type II (NaPi-2b) and type III (PiT-1, PiT-2) Na-Pi transporter mRNA abundance determined by quantitative PCR in rats. AU, arbitrary units. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

Isolation of brush border membrane vesicles.

Rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (Pentothal, Abbott; 100 mg/kg ip). The renal vessels were clamped off, and the kidneys were removed and processed for brush border membrane (BBM) vesicle (BBMV) isolation, as described previously (12). The full small intestine (∼90 cm) was removed, flushed with cold saline solution, and cut into sections as follows: duodenum [the first 10 cm (0–10 cm)], jejunum [the next 20 cm (10–30 cm)], and ileum [the last 30 cm (∼60–90 cm)]. Mucosa scraped from each section was homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer in isolation buffer (300 mM mannitol, 5 mM EGTA, and 15.2 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5). Homogenates were filtered through gauze to remove mucus and centrifuged at 38,000 g for 35 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended with isolation buffer and subjected to the first Mg2+ precipitation step (15 mM Mg2+ final concentration). After centrifugation at 2,500 g for 15 min at 4°C, the supernatant was transferred to a clean tube and centrifuged again at 38,000 g for 35 min at 4°C. The pellet was resuspended in isolation buffer and subjected to the second Mg2+ precipitation under the same conditions and centrifuged at 2,500 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a new tube and centrifuged at 38,000 g for 35 min at 4°C. The final pellet was resuspended in 50–100 μl of 300 mM mannitol and 16 mM HEPES-Tris (pH 7.5) supplemented with Complete Mini Roche protease inhibitor cocktail.

The purity of the BBMV preparation was analyzed by testing the specific activity of several enzymes in homogenate and final BBM fractions, resulting in >15-fold enrichment of the BBM specific enzyme activity compared with the homogenates (∼17-and 65-fold enrichment for leucine aminopeptidase and γ-glutamyl transferase, respectively) and no significant enrichment of Na+-K+-ATPase, a specific marker of basolateral membrane (see supplemental Table 1).

Measurement of Na-Pi transport activity.

Pi transport was measured by radioactive 32Pi uptake in freshly isolated BBMV. Pi uptake in renal proximal tubule BBM was assayed as described elsewhere (33). 32Pi uptake of intestinal BBM was measured in a similar way with some modifications. Briefly, 10 μl of isolated BBM prewarmed to 37°C were incubated with 40 μl of uptake buffer [150 mM NaCl, 16 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), and 0.1 mM K2HPO4] containing K2H32PO4 tracer (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences). After 30 s of incubation at 37°C, uptake buffer was quickly removed by rapid Millipore filtration and washed with ice-cold stop solution (100 mM NaCl, 100 mM mannitol, and 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.5). All uptake measurements were performed in triplicate and expressed as specific activity (pmol Pi·30 s−1·mg BBM protein−1). Na-independent uptake was measured after substitution of choline chloride for NaCl in the uptake buffer. The Na-independent component was subtracted from the total uptake.

Immunoblotting.

Intestinal or renal BBM protein (20 μg) was separated by 7.5% or 10% SDS-PAGE (Criterion, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked for 30 min at room temperature with 5% milk in PBS-Tween 20 buffer (80 mM Na2HPO4, 25 mM NaH2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.5) and then incubated with primary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. After three washes with PBS-Tween 20 buffer, membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat secondary antibodies diluted 1:10,000 for 1 h at room temperature. Enzymatic detection of horseradish peroxidase was carried out by incubation in Supersignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) using the charge-coupled device imaging system in a Bio-Rad imager. Band intensities were quantified using Quantity One software and normalized vs. β-actin (mouse β-actin, Sigma) as control for total protein loading.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

A section of small intestine was removed in all its extension and flushed with cold saline solution. Sections (0.5 cm long) were cut every 10 cm along the entire small intestine. Each section was embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound and “flash-frozen” in liquid nitrogen, and samples were stored at −80°C. Cryostat sections (6 μm) were fixed with acetone at −20°C for 5 min and then washed and incubated with antibodies in PBS. Polyclonal rabbit anti-NaPi-2b antibody was used at 1:100 dilution with overnight incubation at 4°C. Polyclonal chicken anti-PiT-1 antibody was used at 1:50 dilution with overnight incubation at 4°C. Specific secondary antibody link to the fluorescent dye Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 568 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Fluorescence images were acquired on a laser scanning confocal microscope (model 510, Carl Zeiss Microimaging, Thornwood, NY).

RNA isolation and analysis.

Sections of small intestine (see above) were flushed with cold saline solution and homogenized with a Polytron in the presence of RLT buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Total RNA was isolated from the resulting homogenates using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using reverse transcription reagents (Bio-Rad). Using a Bio-Rad iCyCler real-time PCR machine, we determined mRNA levels using the following primers: rat NaPi-2b [5′-CAGAAGGCCAGAACAAGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCAGCAATATGAAGGAGAGG-3′ (reverse)], rat PiT-1 [5′-TGGCTCTGTCAGTGCTATG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGTTCGGACCATTTGATACC-3′ (reverse)], and rat PiT-2 [5′-GTGGATGGAACTCGTCAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGGATGAACAGCACACC-3′ (reverse)]. All the data were calculated from triplicate reactions. Cyclophilin was used as an internal control, and the amount of RNA was calculated by the comparative cycle threshold method, as recommended by the manufacturer.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed for statistical significance by unpaired Student's t-test. Values are means ± SE. Six animals were used per condition in each experiment, and each experiment was repeated three times.

RESULTS

Characterization of specific antibodies against NaPi-2b and PiT-1.

A rabbit polyclonal antibody was raised against a COOH-terminal peptide of rat NaPi-2b. Western blot analyses of intestinal BBM of chronically fed rats resulted in recognition of two bands of ∼85 and ∼110 kDa (and a third ∼130-kDa band under chronic adaptation) (Fig. 1; see Fig. 4). Previous studies have described, in rat and mouse, different-sized bands related to different degrees of glycosylation (2, 32). Immunofluorescence microscopy of intestinal sections using the same antibody stained the apical membrane of the enterocytes on the villi (Fig. 2).

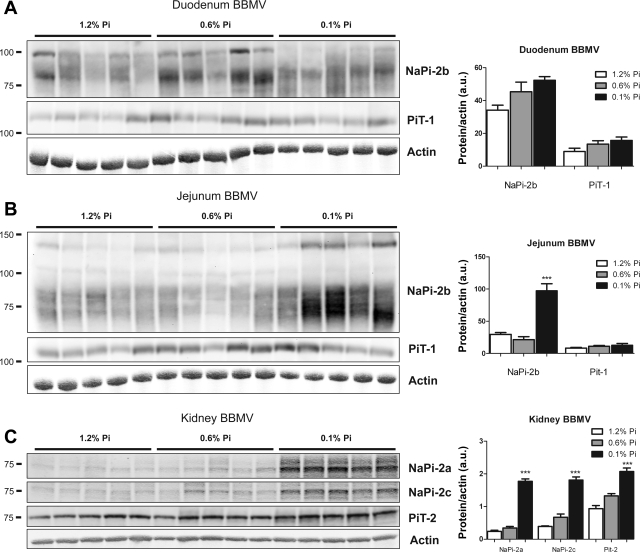

Fig. 4.

BBMV Na-Pi protein regulation in rats chronically fed high-, normal-, or low-Pi diet. BBMV NaPi-2b and PiT-1 protein abundance was determined by Western blot analysis in duodenum (A) and jejunum (B). NaPi-2b protein abundance is markedly and significantly increased in response to chronic low-Pi diet in jejunal BBMV. There is a gradual increase in duodenal BBMV NaPi-2b abundance that did not reach statistical significance. C: upregulation of NaPi-2a, NaPi-2c, and PiT-2 protein abundance in kidney SC-BBMV in response to chronic low-Pi diet. Densitometry analysis was performed for each section; results were normalized to actin expression. ***P < 0.001.

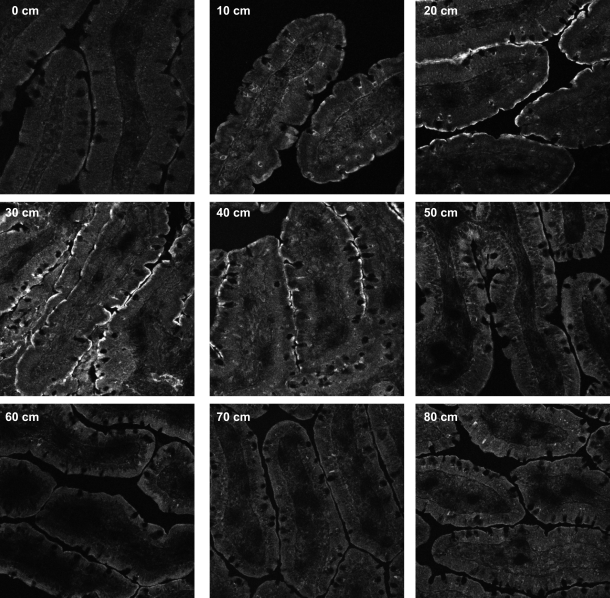

Fig. 2.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of rat small intestine sections showing NaPi-2b expression on apical membrane of enterocytes. NaPi-2b signal is weak in duodenum (0–10 cm), intense in jejunum (20–40 cm), and negligible in ileum (50–80 cm). Sections (0.5 cm) were obtained from rats that were chronically fed the low-Pi (0.1%) diet, fixed with methanol, stained with anti-NaPi-2b antibody, and examined at 10-cm intervals along the small intestine.

A specific peptide located in the extracellular loop between the fourth and fifth transmembrane domain of rat PiT-1 was used to raise polyclonal antibodies. Rabbit anti-PiT-1 was successfully used for detection of PiT-1 by Western blot. A single sharp band at ∼120 kDa corresponding to PiT-1 was detected in BBM derived from rat small intestine. A different antibody raised in chicken against the same peptide was needed for immunofluorescence microscopy. The specificity of the antibodies was tested by blocking with the corresponding antigenic peptide (see supplemental Fig. 1).

Expression of Na-Pi transporters along rat small intestine.

Pi uptake assays in BBMV were performed to evaluate transcellular Pi absorption in the different segments of the small intestine. The Na-independent component, determined after substitution of choline chloride for NaCl in the buffer, was a small portion of the total Pi uptake (see supplemental Fig. 3) and was subtracted from total uptake. Pi uptake measurements of intestinal BBMV showed that Na-dependent Pi activity was higher in the duodenum and jejunum and negligible in the ileum (Fig. 1A).

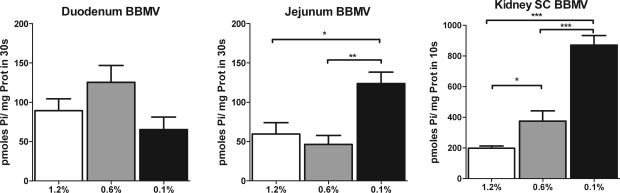

Fig. 3.

Effects of dietary Pi on intestinal and renal BBMV Pi transport activity. Na-Pi transporter uptake was measured in BBMV of duodenum (A) and jejunum (B) of rats chronically fed high-Pi (1.2%), normal-Pi (0.6%), or low-Pi (0.1%) diet. Pi uptake in BBMV from jejunum was increased 67% in rats fed the low-Pi diet compared with rats fed the high-Pi diet (59.6 ± 14.2, 46.3 ± 11.4, and 123.9 ± 14.3 pmol Pi·mg protein−1·30 s−1 for rats fed 1.2%, 0.6%, and 0.1% Pi, respectively). No significant regulation is observed in BBMV from duodenum. C: progressive upregulation of phosphate uptake in BBMV isolated from kidney superficial cortex (SC-BBMV) in rats fed normal-Pi and low-Pi diet compared with rats fed high-Pi diet. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

The expression profile of NaPi-2b protein along the rat small intestine coincides with the distribution of the transcellular Pi uptake activity, with expression of the transporter in the duodenum and jejunum (Fig. 1B). However, NaPi-2b protein expression is significantly higher in the jejunum, whereas Na-Pi uptake activity in BBMV is higher in the duodenum.

NaPi-2b has been considered the main Na-Pi transporter involved in intestinal Pi absorption. In view of the recent characterization of the expression and regulation of the renal proximal tubular apical membrane type III Na-Pi transporter PiT-2 (31), we also examined the mRNA expression levels of the type III Na-Pi transporters in the small intestine. PiT-1 mRNA was expressed in all three intestinal segments, with the highest expression in the ileum (Fig. 1C). However, PiT-2 mRNA expression was minimal along the entire small intestine compared with the other two Na-Pi transporters (Fig. 1C).

We found specific expression of PiT-1 protein in the apical membrane of the enterocytes. It was assumed that PiT-1 is located in the basolateral membrane (3, 15). We confirmed the expression of PiT-1 protein in BBM of the duodenum and jejunum, but not in the ileum, by Western blot (Fig. 1B). PiT-1 protein shows the same expression pattern as NaPi-2b, with higher protein levels in the jejunum than duodenum, which suggests that PiT-1 could play a role in transcellular Pi absorption in these segments.

The expression of NaPi-2b and PiT-1 protein in the apical membrane of the enterocytes was confirmed by immunostaining of small intestinal sections and colocalization with phalloidin-stained actin (see supplemental Fig. 2). The expression profile along the entire small intestine of NaPi-2b protein by immunofluorescence microscopy paralleled the expression profile shown by Western blotting: lower NaPi-2b expression in the duodenum (corresponding to 0 and 10 cm in Fig. 2) and higher NaPi-2b expression in the jejunum (corresponding to 20, 30, and 40 cm). Expression of NaPi-2b protein in the ileum was also undetectable by immunofluorescence, in accordance with the Western blot results.

Effects of chronic alterations of dietary Pi on regulation of intestinal Na-Pi transporter activity, protein, and mRNA.

Intestinal BBMV were isolated from rats chronically fed the 0.1, 0.6, or 1.2% Pi diet. Pi uptake activity was determined in BBMV isolated from the duodenum and jejunum (Fig. 3). Jejunal BBMV isolated from rats chronically fed the low-Pi (0.1%) diet showed a 67% increase in the Na-dependent Pi uptake compared with BBMV isolated from rats fed the normal-Pi (0.6%) or high-Pi (1.2%) diet. However, there were no significant differences in the duodenal BBMV Pi transport activity among the three Pi diets.

Kidney BBMV isolated from the same animals showed, as expected, a progressive and stepwise upregulation of Na-Pi uptake with the 0.6% and 0.1% Pi diets compared with the 1.2% Pi diet (Fig. 3). In contrast to the kidney, there was no progressive stepwise increase in Na-Pi activity in the jejunum, with no significant differences between the 0.6% and 1.2% Pi diets.

NaPi-2b and PiT-1 protein levels were determined in BBMV isolated from the duodenum and jejunum by Western blotting (Fig. 4, A and B). Duodenal BBM did not show significant changes in NaPi-2b expression. However, BBM isolated from the jejunum of rats fed the 0.1% Pi diet showed an upregulation of NaPi-2b total protein expression. Although the 85-kDa band showed a marked upregulation, the 110-kDa band did not show significant changes. Moreover, a new larger (∼130-kDa) band appeared also to be upregulated in rats fed the 0.1% Pi diet. PiT-1 protein expression in BBM did not change in the duodenum or jejunum as a function of dietary Pi.

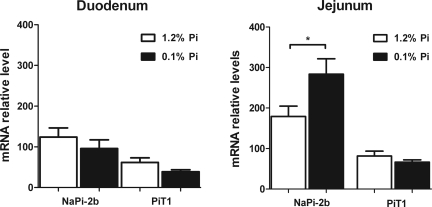

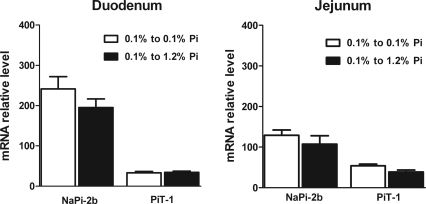

Quantification of mRNA levels of the Na-Pi cotransporters showed a significant increase of NaPi-2b mRNA levels in the jejunum of rats fed the 0.1% Pi diet. This implies that chronic adaptation to the low-Pi diet is at least in part mediated by transcriptional mechanisms (Fig. 5). NaPi-2b mRNA expression was unchanged in the duodenum. Furthermore, there were no changes in PiT-1 mRNA levels in either of these intestinal segments.

Fig. 5.

Intestinal Na-Pi mRNA regulation in rats chronically fed high- or low-Pi diet. In jejunum, NaPi-2b mRNA abundance is increased in parallel with increases in BBM NaPi-2b protein abundance and BBM Pi uptake in response to chronic low-Pi diet. There are no changes in jejunal PiT-1 mRNA or duodenal NaPi-2b or PiT-1 mRNA abundance in response to low-Pi diet. *P < 0.05.

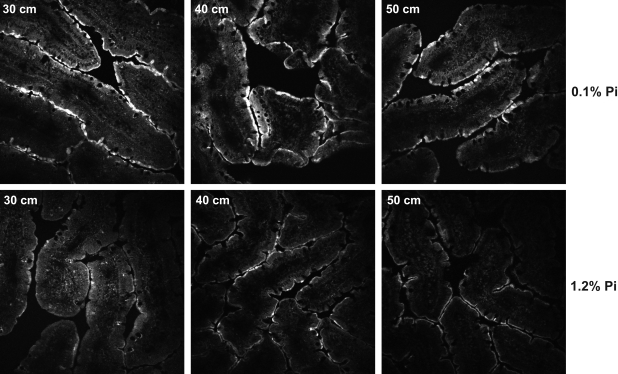

Intestinal sections of the proximal and distal jejunum (30, 40, and 50 cm) were stained with antibodies against NaPi-2b and analyzed by immunofluorescence. There was a marked increase in NaPi-2b protein intensity in the apical membrane of the enterocytes in the jejunum of rats fed the low-Pi diet (Fig. 6), confirming the results obtained by Western blotting.

Fig. 6.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of NaPi-2b protein in intestinal sections corresponding to rat jejunum (30–50 cm). Abundance of NaPi-2b protein is increased in apical membrane of enterocytes in rats chronically fed low-Pi diet. Sections were embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound, fixed with methanol, and stained with anti-NaPi-2b antibody.

Changes in serum Pi levels under different dietary Pi conditions.

We measured serum Pi concentration of rats fed the different Pi diets. It was clear that the adaptation to the different dietary Pi conditions induced dramatic changes in the serum Pi levels in the rat. First, rats fed the high- and normal-Pi diets ad libitum showed 1.7- and 1.5-fold increases, respectively, in serum Pi compared with rats fed the low-Pi diet (8.3 ± 0.9 vs. 7.4 ± 0.7 vs. 4.9 ± 0.6 mg Pi/dl). Rats fed acutely the low-Pi diet after 20 h of fasting showed the same serum Pi level as rats fed the low-Pi diet ad libitum (Fig. 7). However, when the rats were fed acutely the high-Pi diet, there was a drastic (>3-fold) increase in serum Pi levels 2 and 4 h after feeding (4.7 ± 0.2 vs. 14.6 ± 4.3 vs. 17.2 ± 1.8 mg Pi/dl). This marked increase in serum Pi levels suggests a regulatory increase in the Pi absorption rate in the small intestine as a result of acute feeding of the high-Pi diet.

Fig. 7.

Effects of dietary Pi on serum Pi levels. A: serum Pi levels of rats chronically fed high-, normal-, or low-Pi diet. Serum Pi concentration is significantly lower in rats chronically fed low-Pi diet than in rats fed high- or normal-Pi diet. B: serum Pi concentration is markedly increased (to levels as high as 16 mg/dl) in rats chronically fed low-Pi diet when they are acutely fed high-Pi diet as early as 2 h after the high-Pi diet. There are no significant changes in serum Pi concentrations between rats chronically low-Pi diet and those trained to eat a low-Pi diet for 4 h/day for 7 days and then acutely fed the same low-Pi diet (chronic low-Pi diet to acute low-Pi diet). **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

In rats chronically adapted to a low-Pi diet, acute feeding of a high-Pi diet induces a marked increase in intestinal Pi absorption in the duodenum, resulting in a dramatic increase in serum Pi.

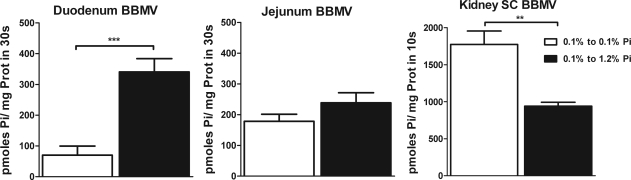

For these studies, rats were trained to eat their diets during a 4-h period everyday for 7 days. On the 8th day, rats that were chronically adapted on a low-Pi diet were fed acutely a low-Pi diet or a high-Pi diet for 4 h. In BBMV isolated from the duodenum, there was a fivefold increase in the Pi uptake rate when the rats were switched from a chronic low-Pi to an acute high-Pi diet (Fig. 8). In contrast, in BBMV isolated from the jejunum, there was no change in Pi uptake under the same conditions, indicating a regulatory adaptation different from that in chronic conditions.

Fig. 8.

Na-dependent Pi uptake in BBMV of rats chronically adapted to a low-Pi diet and then fed low- or high-Pi diet for 4 h. Duodenal and jejunal BBMV show an unexpected reverse adaptation to the change from low- to high-Pi diet compared with renal BBMV. Duodenal and jejunal BBMV demonstrate an increased Na-Pi transport activity, whereas kidney superficial cortex BBMV (SC BBMV) show a decreased Na-Pi transport activity, in response to an acute challenge with high-Pi diet. **P < 0.01. ***P < 0.001.

The increased Pi uptake activity in the duodenal segment can explain the marked and dramatic increase in the serum Pi levels observed in rats fed acutely a high-Pi diet (Fig. 7). In contrast to the duodenum, in BBM isolated from the kidney, in the same experiments and in parallel, there was an adaptive decrease in BBM Na-Pi transport activity (Fig. 8).

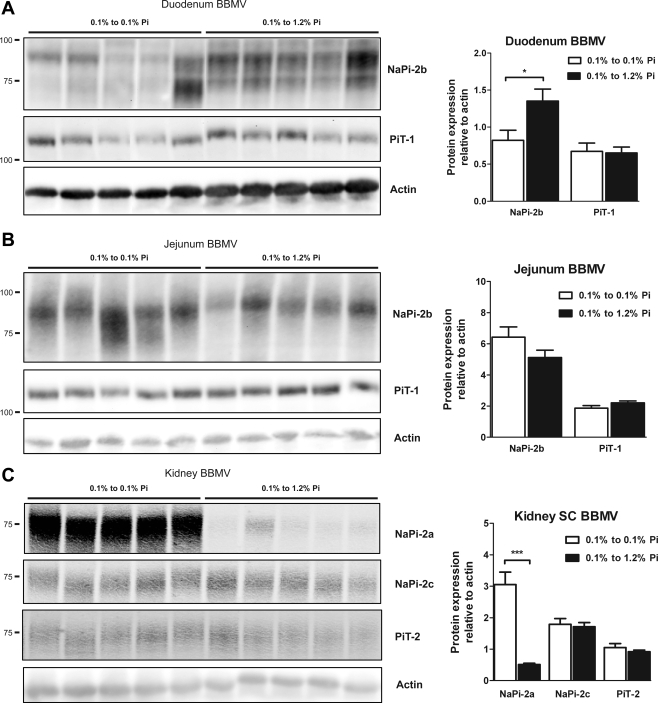

The increase in BBMV Pi uptake in the duodenum was associated with an increase in NaPi-2b protein abundance in the absence of any changes in PiT-1 protein abundance (Fig. 9). There were no changes in NaPi-2b or PiT-1 protein abundance in BBM isolated from the jejunum, and also there were no changes in NaPi-2b mRNA abundance in the duodenum or jejunum (Fig. 10).

Fig. 9.

Duodenal (A), jejunal (B), and renal (C) BBMV Na-Pi protein regulation in rats chronically adapted to low-Pi diet and then fed low- or high-Pi diet for 4 h. There is a significant increase in duodenal BBMV NaPi-2b protein abundance. No significant changes in NaPi-2b protein expression in jejunal BBMV or duodenal and jejunal PiT-1 protein expression were observed. In kidney superficial cortex BBMV, there is a marked and significant decrease in NaPi-2a protein abundance, whereas there are no changes in NaPi-2c or PiT-2 protein abundance in response to acute high-Pi diet for 4 h. *P < 0.05. ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 10.

NaPi-2b and PiT-1 mRNA regulation in rats chronically adapted to low-Pi diet and then fed low- or high-Pi diet for 4 h. There are no significant changes in NaPi-2b or PiT-1 mRNA abundance in response to acute (4 h) changes in dietary Pi.

DISCUSSION

Cardiovascular disease in CKD patients has emerged as one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality. CKD-associated hyperphosphatemia is one of the factors that can promote vascular stiffness and vascular calcification and is one of the pharmacological targets selected to reduce the impact on cardiovascular disease (1, 21). Although there are treatments to reduce hyperphosphatemia, a detailed knowledge of the mechanisms of intestinal Pi absorption and its regulation by dietary Pi uptake is crucial for development of more efficient and specific treatment modalities.

In this study, we found that NaPi-2b protein expression is highest in the BBM of rat jejunum. This finding is in agreement with a previous study that showed the highest NaPi-2b mRNA expression in rat jejunum as well (19). However, it was surprising that BBM Na-Pi cotransport activity was highest in the duodenum, despite lower NaPi-2b protein and mRNA expression than in the jejunum. The equilibrium values of Pi uptake determined in duodenal and jejunal BBMV were very similar, suggesting that this discrepancy was not induced by differences in intravesicular space/total protein rates (see supplemental Fig. 4). Posttranslational modification of NaPi-2b protein and/or the presence of additional Na-Pi transporters playing different roles in the duodenum and the jejunum could explain the discrepancy between Na-Pi cotransport activity and NaPi-2b protein expression. Posttranslational modifications of NaPi-2b described in previous studies include glycosylation (2), ubiquitination (25), and palmitoylation (20). However, the role of these modifications in modulation of the activity or trafficking of the intestinal Na-Pi transporters needs to be determined.

In regard to the potential presence of additional Na-Pi transporters, we also identified PiT-1 expression in the small intestine. Expression of type III Na-Pi transporters in the small intestine was detected by mRNA analysis (3, 14). Until recently, type III Na-Pi transporters (PiT-1 and PiT-2) were assumed to be expressed ubiquitously, acting like Pi housekeeping basolateral transporters (3, 14). However, we report here PiT-1 expression in the apical membrane of enterocytes, suggesting that PiT-1 could play a role in Pi absorption in the small intestine under physiological conditions. This conclusion is supported by the partial inhibition of Pi transport activity in jejunal BBMV by low concentrations of phosphonoformic acid (18) (see supplemental Fig. 5). Several studies have shown that phosphonoformic acid is a stronger inhibitor for type II Na-Pi transporters (NaPi-2b) but a weaker inhibitor of type III Na-Pi transporters (PiT-1 and PiT-2) (27, 30). PiT-1 protein also showed an expression pattern similar to that of NaPi-2b protein, with higher levels in the duodenum and jejunum. However, the relative importance of PiT-1 in transcellular Pi absorption and the putative role of posttranscriptional regulation of the activity of both transporters need to be determined.

Our results suggest that intestinal Pi absorption in rats is concentrated in the duodenum and jejunum and is negligible in the ileum, in accordance with previous studies. However, caution is needed in evaluating the data derived from in vitro studies. Using a compartmental analysis method, Kayne et al. (16) showed that the final part of the ileum, or distal segment 2, can play a role as important as the duodenum in intestinal Pi absorption. Although the Pi absorption rate is 50 times higher in the duodenum than in the ileum, the mean residence time of Pi is much higher in the last section, resulting in similar Pi absorption rates. Whether low expression levels of NaPi-2b or PiT-1 in the ileum contribute to this component of the total Pi absorption is unknown. In this study, we were not able to detect apical expression of NaPi-2b or PiT-1 transporters in the ileum. Paracellular transport is also contributing to the overall transport of Pi and, most likely, could be also regulated under different dietary conditions. Although we have not studied the contribution of the paracellular transport, other recent studies have addressed the relative importance of both pathways. Eto et al. (9) used voltage-clamp analysis to differentiate the paracellular from the transcellular component of rat jejunum. Their results show a more important role of the transcellular pathway under these experimental conditions and indicate a greater contribution to Pi permeation by the transcellular than the paracellular route, with contributions of 78% and 22%, respectively. More recently, using inducible NaPi-2b knockout mice, Sabbagh et al. (28) also showed the importance of the NaPi-2b transporter in intestinal Pi absorption.

Our study also established the regulation of NaPi-2b and PiT-1 transporters with chronic and acute changes in dietary Pi intake. Jejunal transcellular Pi absorption rate, evaluated as BBMV Na-Pi uptake activity, is increased in animals adapted to a chronic low-Pi (0.1%) diet for 7 days compared with animals adapted to normal-Pi (0.6%) and high-Pi (1.2%) diets. In contrast, no significant response is observed in duodenal BBMV. The increase in Na-Pi transport activity is associated with parallel increases in NaPi-2b protein and mRNA in the jejunum, whereas PiT-1 did not show significant changes in protein or mRNA levels. In the kidney, the increase in BBM Na-Pi cotransport activity was paralleled by increases in BBM NaPi-2a, NaPi-2c, and PiT-2 protein abundance. Combined adaptation of the intestinal jejunum and kidney proximal tubule to increased Pi absorption rate in the small intestine and Pi reabsorption in the kidney may be designed to allow the rats to maintain Pi homeostasis. However, this adaptive mechanism is not completely able to maintain serum Pi levels in animals fed a low-Pi diet, as indicated by a significantly lower serum Pi in rats fed a low-Pi diet (7.4 ± 0.7 and 4.9 ± 0.6 mg Pi/dl in rats fed a normal- and a low-Pi diet, respectively).

In contrast, rats fed a low-Pi diet for 1 wk and then acutely adapted to a high-Pi diet show an unexpected marked increase in duodenal BBM Na-Pi cotransport activity associated with a parallel increase in duodenal BBM NaPi-2b protein abundance in the absence of significant changes in the jejunum. More interestingly, these animals show a marked increase in serum Pi after 2 and 4 h on the high-Pi diet. The unexpected increase in duodenal Na-Pi cotransport activity and NaPi-2b protein expression contributes to the transitory hyperphosphatemia and, therefore, represents a fully maladaptive response.

Most human physiological studies have focused on random or fasting measurements of Pi serum, but recent studies have addressed the postprandial adaptive changes in response to different levels of dietary Pi. In subjects fed a high-Pi diet, a significant postprandial elevation of serum Pi, with a peak value exceeding the normal range at 2 h, was observed (24). However, high-Pi diet-induced hyperphosphatemia seems to be milder in humans than in rats (13, 24). The increase in serum Pi (from 3.5 to 5.0 mg/dl) was not as dramatic as that in our rats fed the high-Pi diet (from 5 to 17 mg/dl). Nevertheless, these postprandial changes in serum Pi have also been associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, even in healthy subjects (29).

CKD patients could be even more susceptible to the postprandial transitory hyperphosphatemia. First, they have impaired Pi renal excretion and hormonal adaptive response complicating Pi homeostasis. Moreover, they are often under dietary Pi restriction and Pi binder treatment (equivalent to a low-Pi diet in our study), which could induce a higher response of the duodenum, as we show in our study. For these reasons, NaPi-2b may be considered a target for specific therapy to prevent hyperphosphatemia and its associated complications, especially in CKD patients.

In contrast, as expected, there was a decrease in renal BBM Na-Pi cotransport activity that was accompanied by decreases in BBM NaPi-2a, but not NaPi-2c and PiT-2, protein abundance. It has been proposed that the renal Na-Pi transporters have a different temporal response to different stimuli (23, 31). NaPi-2a shows the fastest response to acute changes in dietary phosphate, whereas the other transporters need more time to adapt their expression. However, the fast downregulation of NaPi-2a to compensate for the Pi overload did not prevent the postprandial increase in serum Pi after 4 h of refeeding.

In conclusion, we determined the protein expression of the Na-Pi transporters NaPi-2b and PiT-1 in the apical membrane of rat enterocytes. NaPi-2b plays a major role in the adaptation to chronic and acute alterations in dietary phosphate, whereas the relative contribution of PiT-1 to intestinal Pi absorption remains to be determined. The dietary adaptation of NaPi-2b in the duodenum is different from that in the jejunum, suggesting different regulatory mechanisms. Although the jejunum seems to play a more important role in the chronic adaptation to a low-Pi diet, the duodenum plays a major role in the acute response to a high-Pi diet, with the increase in Pi reabsorption inducing an increase in serum Pi. Transitory postprandial hyperphosphatemia after a high-Pi diet is induced, at least partially, by increased NaPi-2b activity in the duodenum, suggesting that NaPi-2b could be a potential target for treatment of hyperphosphatemia.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01 DK-066029 (to M. Levi and N. Barry), American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award 0520054Z (to S. Breusegem) and Scientist Development Grant 0830394N (to J. Blaine), National Institute on Aging Minority Fellowship 3R01 AG-026529 (to Y. Caldas), and Genzyme Award PN200708-073 (to M. Levi and H. Giral).

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Adeney KL, Siscovick DS, Ix JH, Seliger SL, Shlipak MG, Jenny NS, Kestenbaum BR. Association of serum phosphate with vascular and valvular calcification in moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 381–387, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arima K, Hines ER, Kiela PR, Drees JB, Collins JF, Ghishan FK. Glucocorticoid regulation and glycosylation of mouse intestinal type IIb Na-Pi cotransporter during ontogeny. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283: G426–G434, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai L, Collins JF, Ghishan FK. Cloning and characterization of a type III Na-dependent phosphate cotransporter from mouse intestine. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1135–C1143, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Block GA, Hulbert-Shearon TE, Levin NW, Port FK. Association of serum phosphorus and calcium × phosphate product with mortality risk in chronic hemodialysis patients: a national study. Am J Kidney Dis 31: 607–617, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Capuano P, Radanovic T, Wagner CA, Bacic D, Kato S, Uchiyama Y, St-Arnoud R, Murer H, Biber J. Intestinal and renal adaptation to a low-Pi diet of type II NaPi cotransporters in vitamin D receptor- and 1α-OHase-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C429–C434, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cizman B. Hyperphosphataemia and treatment with sevelamer in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18Suppl 5: v47–v49, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cozzolino M, Staniforth ME, Liapis H, Finch J, Burke SK, Dusso AS, Slatopolsky E. Sevelamer hydrochloride attenuates kidney and cardiovascular calcifications in long-term experimental uremia. Kidney Int 64: 1653–1661, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cozzolino M, Brancaccio D. Hyperphosphatemia in dialysis patients: the therapeutic role of lanthanum carbonate. Int J Artif Organs 30: 293–300, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eto N, Tomita M, Hayashi M. NaPi-mediated transcellular permeation is the dominant route in intestinal inorganic phosphate absorption in rats. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet 21: 217–221, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedman EA. An introduction to phosphate binders for the treatment of hyperphosphatemia in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl S2–S6, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hattenhauer O, Traebert M, Murer H, Biber J. Regulation of small intestinal Na-Pi type IIb cotransporter by dietary phosphate intake. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G756–G762, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inoue M, Digman MA, Cheng M, Breusegem SY, Halaihel N, Sorribas V, Mantulin WW, Gratton E, Barry NP, Levi M. Partitioning of NaPi cotransporter in cholesterol-, sphingomyelin-, and glycosphingolipid-enriched membrane domains modulates NaPi protein diffusion, clustering, and activity. J Biol Chem 279: 49160–49171, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isakova T, Gutierrez O, Shah A, Castaldo L, Holmes J, Lee H, Wolf M. Postprandial mineral metabolism and secondary hyperparathyroidism in early CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 615–623, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katai K, Miyamoto K, Kishida S, Segawa H, Nii T, Tanaka H, Tani Y, Arai H, Tatsumi S, Morita K, Taketani Y, Takeda E. Regulation of intestinal Na+-dependent phosphate co-transporters by a low-phosphate diet and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Biochem J 343: 705–712, 1999 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kavanaugh MP, Miller DG, Zhang W, Law W, Kozak SL, Kabat D, Miller AD. Cell-surface receptors for gibbon ape leukemia virus and amphotropic murine retrovirus are inducible sodium-dependent phosphate symporters. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 7071–7075, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kayne LH, D'Argenio DZ, Meyer JH, Hu MS, Jamgotchian N, Lee DB. Analysis of segmental phosphate absorption in intact rats. A compartmental analysis approach. J Clin Invest 91: 915–922, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kestenbaum B. Phosphate metabolism in the setting of chronic kidney disease: significance and recommendations for treatment. Semin Dial 20: 286–294, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loghman-Adham M, Levi M, Scherer SA, Motock GT, Totzke MT. Phosphonoformic acid blunts adaptive response of renal and intestinal Pi transport. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 265: F756–F763, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marks J, Srai SK, Biber J, Murer H, Unwin RJ, Debnam ES. Intestinal phosphate absorption and the effect of vitamin D: a comparison of rats with mice. Exp Physiol 91: 531–537, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McHaffie GS, Graham C, Kohl B, Strunck-Warnecke U, Werner A. The role of an intracellular cysteine stretch in the sorting of the type II Na/phosphate cotransporter. Biochim Biophys Acta 1768: 2099–2106, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Menon V, Greene T, Pereira AA, Wang X, Beck GJ, Kusek JW, Collins AJ, Levey AS, Sarnak MJ. Relationship of phosphorus and calcium-phosphorus product with mortality in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 46: 455–463, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyamoto K, Ito M, Kuwahata M, Kato S, Segawa H. Inhibition of intestinal sodium-dependent inorganic phosphate transport by fibroblast growth factor 23. Ther Apher Dial 9: 331–335, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moe OW. PiT-2 coming out of the pits. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F689–F690, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishida Y, Taketani Y, Yamanaka-Okumura H, Imamura F, Taniguchi A, Sato T, Shuto E, Nashiki K, Arai H, Yamamoto H, Takeda E. Acute effect of oral phosphate loading on serum fibroblast growth factor 23 levels in healthy men. Kidney Int 70: 2141–2147, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmada M, Dieter M, Speil A, Bohmer C, Mack AF, Wagner HJ, Klingel K, Kandolf R, Murer H, Biber J, Closs EI, Lang F. Regulation of intestinal phosphate cotransporter NaPi IIb by ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2 and by serum- and glucocorticoid-dependent kinase 1. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G143–G150, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raggi P, Boulay A, Chasan-Taber S, Amin N, Dillon M, Burke SK, Chertow GM. Cardiac calcification in adult hemodialysis patients. A link between end-stage renal disease and cardiovascular disease? J Am Coll Cardiol 39: 695–701, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ravera S, Virkki LV, Murer H, Forster IC. Deciphering PiT transport kinetics and substrate specificity using electrophysiology and flux measurements. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C606–C620, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sabbagh Y, O'Brien SP, Song W, Boulanger JH, Stockmann A, Arbeeny C, Schiavi SC. Intestinal Npt2b is an active component of systemic phosphate regulation. J Am Soc Nephrol In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shuto E, Taketani Y, Tanaka R, Harada N, Isshiki M, Sato M, Nashiki K, Amo K, Yamamoto H, Higashi Y, Nakaya Y, Takeda E. Dietary phosphorus acutely impairs endothelial function. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1504–1512, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villa-Bellosta R, Bogaert YE, Levi M, Sorribas V. Characterization of phosphate transport in rat vascular smooth muscle cells: implications for vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1030–1036, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villa-Bellosta R, Ravera S, Sorribas V, Stange G, Levi M, Murer H, Biber J, Forster IC. The Na+-Pi cotransporter PiT-2 (SLC20A2) is expressed in the apical membrane of rat renal proximal tubules and regulated by dietary Pi. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 296: F691–F699, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu H, Uno JK, Inouye M, Xu L, Drees JB, Collins JF, Ghishan FK. Regulation of intestinal NaPi-IIb cotransporter gene expression by estrogen. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 285: G1317–G1324, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zajicek HK, Wang H, Puttaparthi K, Halaihel N, Markovich D, Shayman J, Beliveau R, Wilson P, Rogers T, Levi M. Glycosphingolipids modulate renal phosphate transport in potassium deficiency. Kidney Int 60: 694–704, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.