Abstract

Tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues (TIP39) is a member of the parathyroid hormone (PTH) family of peptide hormones that exerts its function by interacting with the PTH type 2 receptor (PTH2R). Presently, no known function has been attributed to this signaling pathway in the developing skeleton. We observed that TIP39 and PTH2R were present in the newborn mouse growth plate, with the receptor localizing in the resting zone whereas ligand expression was restricted exclusively in prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes. By 8 wk of life, PTH2R, and to a lesser degree TIP39, immunoreactivity was present in articular chondrocytes. We therefore sought to investigate the role of TIP39/PTH2R signaling in chondrocytes by generating stably transfected CFK2 chondrocytic cells overexpressing PTH2R (CFK2R). TIP39 treatment of CFK2R clones in culture inhibited their proliferation by restricting cells at the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, coupled with decreased expression and activity of cyclin-dependent kinases Cdk2 and Cdk4, while p21, an inhibitor of Cdks, was upregulated. In addition, TIP39 treatment decreased expression of differentiation markers in these cells associated with marked alterations in extracellular matrix and metalloproteinase expression. Transcription of Sox9, the master regulator of cartilage differentiation, was reduced in TIP39-treated CFK2R clones. Moreover, Sox9 promoter activity, as measured by luciferase reporter assay, was markedly diminished after TIP39 treatment. In summary, our results show that TIP39/PTH2R signaling inhibits proliferation and alters differentiation of chondrocytes by modulating SOX9 expression, thereby substantiating the functional significance of this signaling pathway in chondrocyte biology.

Keywords: growth plate, cell cycle, osteoarthritis, secondary ossification center, Sox9

the mammalian parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor family includes PTH1 and PTH2 receptors (PTH1R and PTH2R, respectively) and three related ligands [PTH, PTH-related protein (PTHrP), and tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues (TIP39)] (9). PTH1R is activated by PTH and PTHrP but not by TIP39. On the other hand, the human (but not rodent) PTH2R is activated by PTH and TIP39 but not by PTHrP (35). PTH, whose expression is strictly confined to the parathyroid gland, acts in a classic endocrine fashion to regulate calcium and phosphate homeostasis. In contrast, PTHrP is expressed in almost all tissues and acts in an autocrine/paracrine or intracrine fashion to regulate a variety of cellular processes (reviewed in Ref. 43). Expression of PTH2R and its natural ligand TIP39 has been reported in the hypothalamus and other parts of the brain, and experimental evidence suggests that TIP39 signaling modulates nociception or the regulatory network of anxiety and depression (41). Nevertheless, the distribution of PTH2R and TIP39 in tissues outside the central nervous system suggests other potential physiological actions for this signaling pathway (36, 39).

Endochondral bone formation is a dynamic, highly orchestrated process in which cartilaginous skeletal structures are replaced by bone (reviewed in Ref. 5). Chondrocytes undergo a process of terminal differentiation or maturation, during which the rate of proliferation decreases, cells become hypertrophic, and the extracellular matrix is altered by production of collagen type X as well as proteins that promote mineralization. The mineralized matrix then serves as template for bone deposition. This process is responsible for most longitudinal bone growth, both during embryonic development and in the postnatal state. Numerous signaling molecules have been implicated in the regulation of this process, including the PTHrP/PTH1R signaling system (16, 18, 19, 22, 31). PTHrP, expressed by perichondrial cells and early proliferating chondrocytes, is proposed to diffuse away from its site of production and act on PTH1R-bearing cells expressed at low levels by proliferating chondrocytes, but at substantially higher levels once these cells stop proliferating (reviewed in Ref. 21). PTHrP maintains chondrocytes in a proliferative state and delays hypertrophy. PTH1R, like PTH2R, is a G protein-coupled receptor, and activation of Gsα-dependent signaling pathway mediates the inhibition of chondrocyte hypertrophy by PTHrP. Thus PTHrP stimulates protein kinase A-dependent phosphorylation of the transcription factor SOX9, and thus activates it. In turn, SOX9 promotes chondrocyte proliferation and delays hypertrophy, and therefore helps mediate this effect of PTHrP (13). In addition, PTHrP suppresses Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) production, required for hypertrophic differentiation of chondrocytes, thereby also contributing to the PTHrP-induced delay in chondrocyte differentiation (10).

The similarity between the two PTH receptors notwithstanding, the functional significance of TIP39/PTH2R in endochondral bone formation, if any, has not been investigated. Immunolocalization of the receptor has been observed primarily in growth plate chondrocytes and subarticular cartilage, with particular emphasis in the developing bone (38). Nevertheless, the expression pattern of its ligand, TIP39, within the developing skeleton has not been reported.

Here we have investigated the role of TIP39/PTH2R signaling in endochondral bone development. We first examined and compared the expression of TIP39 and PTH2R in the cartilage of long bones from newborn and 2-mo-old mice. We then assessed the effects of the TIP39/PTH2R signaling system on proliferation and on differentiation functions of chondrocytes in vitro, using a chondrocytic cell line, CFK2, and examined the mechanisms of these effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Immunohistochemical localization of PTHR2 and TIP39 in growth plate and articular cartilage.

All animal experiments were reviewed and approved by the institutional animal care committee. Long bones were collected and fixed in PLP fixative (2% paraformaldehyde containing 0.075 M lysine and 0.01 M sodium periodate solution) overnight at 4°C and subsequently embedded in paraffin block. Sections were deparaffinized, hydrated through 100% to 70% ethanol followed by running water, treated with 0.05% hyaluronidase for 20 min, and washed three times with Tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 [TBST; 20 mM Tris, 0.15 M NaCl, pH 7.6, 0.1% (wt/vol) Tween 20]. Tissue sections were blocked in TBST buffer containing 0.5% BSA and 10% normal goat serum for 1 h. Rabbit polyclonal anti-PTH2R antibodies (Chemicon International and GenWay Biotech) or anti-TIP39 antibody (Abcam) was diluted in the blocking buffer (1:100, 1:250, 1:100, respectively) and applied overnight. Sections were washed with Tris-buffered high-salt saline-Tween 20 [TBST-High NaCl: 20 mM Tris, 1.5 M NaCl, pH 7.6, 1% (wt/vol) Tween 20] once for 10 min, followed by twice in TBST, each time for 5 min. Biotin-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody was diluted (1:200) and applied to the sections for 1 h at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Washings with TBST-High NaCl were performed to remove unbound antibody. ABC-AP solutions were applied to the sections for 45 min at room temperature, and the positive signals were developed by using a mixture of naphthol-phosphate and fast red dye in Tris-malate buffer (pH 9.5) solution.

Staining for differentiation markers.

Cells were stained for proteoglycans, alkaline phosphatase, and mineralization as previously described (30). Over the 14-day period, medium was changed every 3 days, with fresh TIP39 (10−7 M) (Anaspec) added.

Cell culture, proliferation, and cell cycle analysis.

CFK2 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Stable transfectants expressing vector plasmid pcDNA3 (CFK2V) or PTH2R (CFK2R) were selected against G418 (500 μg/ml), and individual clones were selected. Cultured CFK2 cells were assessed for [3H]thymidine incorporation as previously described (12). For cell cycle analysis, transfected cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS for 2 days with or without TIP39 (10−7 M). Cells were trypsinized briefly and suspended in Vindelov's solution [3.4 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.6), 75 μM propidium iodide, 0.1% (vol/vol) Nonidet P-40, 700 U/l RNase A, and 10 μM NaCl]. Nuclei were analyzed in a FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Northern and Western blot analyses.

RNA was isolated from cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). An aliquot of 15 μg was fractionated on a 1% formaldehyde-agarose gel, and separated RNA was transferred to Nytran membrane (Schleicher & Schuell) by capillary transfer with 10× saline sodium citrate (SSC) solution overnight. 32P-labeled full-length cDNA probes were hybridized to the membrane in a hybridization buffer (48% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, 5× SSC, containing 100 μg/ml of salmon sperm DNA) at 42°C overnight. BioMax film was used for autoradiography. For Western blot analysis, total protein extract from cultured cells was prepared and immunoblotted as previously described (30).

Immunoprecipitation and Cdk2 kinase assay.

Cells were washed in cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer at 4°C for 30 min, and lysates were cleared by spinning at 10,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The phosphotransferase activity of Cdk2 was measured by immune complex kinase assay using histone H1b as substrate, as previously described (33).

Cycloheximide chase experiment.

Vector- or PTH2R-transfected CFK2 cells were synchronized by starving cells with serum-free medium for 24 h. Starvation was released by incubating the cells in RPMI medium containing 10% FBS. Cycloheximide was added to the medium at a concentration of 100 μg/ml. Reactions were terminated at various time intervals. Cells were washed twice with ice-cold PBS before total cell lysate was made with RIPA buffer. Fifteen micrograms of cleared lysates was subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by Western blot analysis.

Reverse transcription, semiquantitative, and real-time polymerase chain reactions for gene expression.

Total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen), purified with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), and subjected to analysis. Comparative mRNA expression was determined primarily by semiquantitative RT-PCR with the One-Step RT-PCR kit (Qiagen). Fifty-microliter reaction mixtures containing 1 μg of total RNA from each sample, 2 μl of 10× reaction buffer, 2 μl of nucleotide mixture, 2 μl of enzyme mix, and 1 μl of forward and reverse primers (each 10 μM) were used. RT reactions were performed at 50°C for 40 min, followed by denaturation at 94°C for 10 min. A 30-cycle PCR reaction was performed by denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 58°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min. A final extension was carried out at 72°C for 10 min before the reaction was stopped at 4°C. For Tip39 mRNA 42 cycles of amplification were performed, given the very low abundance of the transcript in CFK2 cells.

Pairs of primers used to amplify by PCR reaction were as follows: rat collagen type II-forward (F) 5′-CCTGCCAGGACCTGAAACTC-3′, rat collagen type II-reverse (R) 5′-TAGAGTGACTGCGGTTAGAAAG-3′; rat collagen type X-F 5′-CTTCACAAAGAGCGGACAGAG-3′, rat collagen type X-R 5′-TATGGGAGCCACTAGGAATC-3′; rat biglycan-F 5′-CAACCGTATCCGCAAAGTGC-3′, rat biglycan-R 5′-CAGGCTCCCATTCTCAATCAT-3′; rat cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (Comp)-F 5′-CGGTGATGGAATGTGATGCTT-3′, rat Comp-R 5′-TTGTTGGACTTAGAGAAGGTC-3′; rat fibronectin-F 5′-CCCCATGAAGCAACGTGTTAT-3′, rat fibronectin-R 5′-CACATCTAACGGCATGAAGCA-3′; rat collagen Iα2-F 5′-ACACTGGTAGAGATGGTGCTC-3′, rat collagen Iα2-R 5′-TCTCCAGAGGGACCCTTTTCA-3′; rat a disintegrin-like and metallopeptidase with thombospondin type 1 motif (Adamts)1-F 5′-TGCAAGGACAGTGTGTGAAAG-3′, rat Adamts1-R 5′-AGCATGGCCCACCATAAG-3′; rat Adamts4-F 5′-TGTGACGCTCTGGGTATG-3′, rat Adamts4-R 5′-CAGCATCATAGTCCTTGC-3′; rat Adamts5-F 5′-CGAGGAAGGTGCGTGAGAAC-3′, rat Adamts5-R 5′-CCTGTCACCCACTGTAGCTG-3′; rat Tip39-F 5′-ATGGTGACATTGAGATTCTG-3′, rat Tip39-R 5′-GTGACAGGCTCTTTATTAGG-3′; rat Runx2-F 5′-CGGGAACCAAGAAGGCACAG-3′, rat Runx2-R 5′-TGCCATTCGAGGTGGTCGTG-3′; mouse Tip39-F 5′-TGGGCGGGATGATGACATTG-3′, mouse Tip39-R 5′-AAGAGAGTGGCGCAGCAAAG-3′; mouse Pth2r-F 5′-TGTCAAGGACAGAGTAGCCC-3′, mouse Pth2r-R 5′-GTGGGTTTGCCAGAGATGAG-3′.

For real-time PCR, total RNA was extracted from cells with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and the relative levels of specific mRNA were determined by the procedure outlined in the LightCycler fastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche) with LightCycler V2.0 (Roche). PCR primers (all 5′ to 3′ direction), amplicon length, and modifications of the amplification conditions were as follows: rat 18S: forward ACGGACCAGAGCGAAAGCAT and reverse TGTCAATCCTGTCCGTGTCC (280-bp product), annealing temperature 60°C with 3 mM MgCl2, and extension time 12 s; rat matrix metallopeptidase (Mmp)13: forward TCTGCACCCTCAGCAGGTTG and reverse CATGAGGTCTCGGGATGGATG (100-bp product), annealing temperature 60°C with 3 mM MgCl2, and extension time 5 s; rat p21: forward GACATCTCAGGGCCGAAAAC and reverse CGGCGCTTGGAGTGATAGAA (74-bp product), annealing temperature 61°C with 3.4 mM MgCl2, and extension time 4 s; rat collagen type II: forward TCCTAAGGGTGCCAATGGTGA and reverse AGGACCAACTTTGCCTTGAGGAC (110-bp product), annealing temperature 60°C with 4 mM MgCl2, and extension time 5 s. Results were normalized to 18S levels.

Sox9 promoter activity.

A 450-bp fragment of the mouse Sox9 promoter region containing the TATA and CAAT box regions was cloned by RT-PCR with the pair of murine primers Sox9-F 5′-TGTGGAGGGTCCTA-3′ and Sox9-R 5′-GACTTCCAGCTCAGGGTCTC-3′. The cloned fragment was sequenced and ligated upstream of the luciferase gene in the reporter plasmid pGL3basic (Promega) to generate a Sox9 promoter-luciferase reporter construct.

Statistical analysis.

Results were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 5.0 software (San Diego, CA). Student's t-test was used to compare data between two groups. Multiple group comparisons were performed by one-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post test. All data are presented as means ± SE. The value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

PTH2R and TIP39 expression in growth plate and articular cartilage.

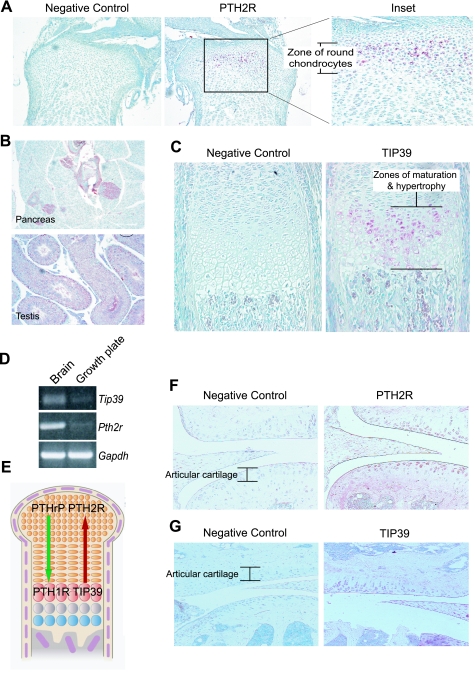

First, we sought to determine whether TIP39/PTH2R signaling plays any role in endochondral bone physiology and homeostasis. Using immunohistochemistry, we examined whether the receptor and ligand are expressed in long bones from newborn mice. Indeed, a strong signal for PTH2R immunoreactivity was observed in round chondrocytes (Fig. 1A), commensurate with previous reports (38). Validation for the specificity of the antibody for the receptor was obtained by staining of the endocrine but not the exocrine pancreas and of sperm cells within the lumen of the epididymis, tissues previously reported to express PTH2R (Fig. 1B) (36, 38). The findings were verified further by using a second anti-PTH2R antibody whose epitope is the first extracellular domain of the human receptor (data not shown). Interestingly, TIP39 expression, not previously reported, was evident in maturing and hypertrophic chondrocytes (Fig. 1C) while being virtually absent from round or flat proliferating chondrocytes. Receptor and ligand expression was corroborated further by PCR amplification of transcripts from growth plates of newborn mice (Fig. 1D). This spatial distribution of ligand and receptor contrasts strikingly with that of PTHrP (expressed in chondrocytes and perichondrial cells at the ends of the developing bones) and its receptor, PTH1R (expressed mainly in maturing chondrocytes), thereby hinting toward a potential setup for cross talk between the two signaling pathways within the developing growth plate (Fig. 1E). By 8 wk of age, PTH2R and TIP39 immunoreactivity was detected in articular chondrocytes, although staining for the ligand was significantly weaker than for the receptor (Fig. 1, F and G). These findings provide evidence that the TIP39/PTH2R signaling system is expressed in growth plate and articular chondrocytes, raising the question of potential functionality in the biology of these cells.

Fig. 1.

Localization of parathyroid hormone (PTH) receptor 2 (PTH2R) and tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues (TIP39) in growth plate and articular chondrocytes. A: sections of long bones from newborn mice were stained in the absence (negative control) or presence of anti-PTH2R antibody (magnification ×50). Chondrocytes in the resting zone stained positive for the receptor. A magnified (×100) section is shown in the inset. B: specificity of the anti-PTH2R antibody was verified further by demonstrating specific staining in the endocrine pancreas and in the testis, specifically in sperm cells within the lumen of the epididymis. C: chondrocytes undergoing hypertrophic transition stained positive for TIP39 expression as shown by immunostaining. Sections without primary antibody (negative control) remained unstained. D: amplification of Pth2r and Tip39 transcripts from newborn mouse growth plate total RNA by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Brain total RNA was used as positive control because expression of receptor and ligand are high in this tissue. E: schematic representation of the localization of PTH-related protein (PTHrP)/PTH type 1 receptor (PTH1R) and TIP39/PTH2R signaling systems within the developing growth plate (adapted with modifications from Ref. 20). F and G: PTH2R (F) and TIP39 (G) expression in articular chondrocytes of mice at 8 wk of age (magnification ×100).

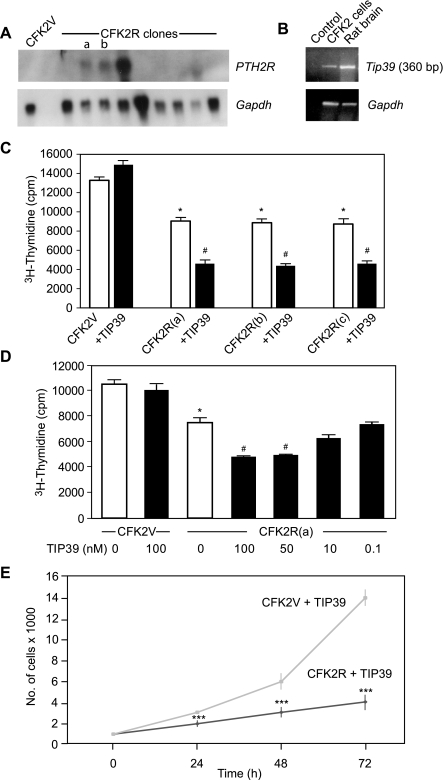

Overexpression of PTH2R in CFK2 cells.

To determine whether TIP39/PTH2R signaling alters chondrocyte biology we overexpressed human PTH2R in CFK2 chondrocytic cells (3), and individual clones were analyzed for receptor mRNA expression. No PTH2R transcripts were observed in the vector-transfected controls (CFK2V), while varying degrees of PTH2R expression were present in CFK2R clones (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, wild-type CFK2 cells did not express endogenous Pth2r transcripts (results not shown), but they did express Tip39, albeit at low levels (Fig. 2B). For most of the in vitro studies described here, at least two different CFK2R clones with moderate levels of receptor expression were used to verify the findings.

Fig. 2.

TIP39/PTH2R signaling decreases chondrocytic CFK2R cell proliferation. A: stable expression of PTH2R in CFK2 cells was determined by Northern blot analysis (top; CFK2R clones a and b are indicated) CFK2V, vector-transfected CFK2 cells. B: Tip39 expression in CFK2 cells as determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR using total RNA. Rat brain total RNA was amplified as positive control, while the negative control lane contained no RNA during amplification. C: [3H]thymidine incorporation in clonal CFK2R cell lines in the presence or absence of TIP39 (10−7 M); a, b, and c refer to the 3 CFK2R clones. Analysis was performed by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni posttest. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with vector-transfected cells without TIP39 treatment; #P < 0.05 compared with vector-transfected cells after TIP39 treatment (n = 3). D: dose response of [3H]thymidine incorporation in CFK2R(a) cells in response to various concentrations of TIP39. Comparisons between groups were made by 1-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni posttest. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 compared with vector-transfected cells without TIP39 treatment; #P < 0.05 compared with PTH2R-transfected cells without TIP39 treatment (n = 3). E: reduction in proliferation rate of CFK2R cells was verified by measuring cell doubling time (representative experiment). Data are means ± SE. ***P < 0.001 compared with vector-transfected cells (n = 3).

TIP39 treatment decreases [3H]thymidine incorporation.

Having established the CFK2R in vitro system, we first set out to examine the effect of TIP39/PTH2R signaling on the proliferation of these cells. Three individual CFK2R clones were grown in culture, and [3H]thymidine incorporation was determined. Treatment of CFK2V cells with TIP39 (10−7 M) did not appreciably change the incorporation of [3H]thymidine (Fig. 2C). On the other hand, in three individual CFK2R clones selected for the experiments, the rate of [3H]thymidine incorporation without TIP39 treatment was ∼30% less compared with CFK2V control cells. This is likely a consequence of endogenous TIP39 expression in these cells, although overexpression or some constitutive activity of the transfected PTH2R cannot be excluded. Moreover, treatment with exogenous TIP39 further reduced [3H]thymidine incorporation by 50% in each of the three independent CFK2R clones. This inhibitory effect of TIP39 on [3H]thymidine incorporation was dose dependent, with maximal effect observed at 10−7 M (Fig. 2D). To further validate TIP39-mediated growth inhibition of CFK2R cells, we performed growth kinetic experiments. As expected, cell doubling time was greater for the TIP39-treated CFK2R cells compared with the CFK2V counterparts (Fig. 2E). These findings further corroborate that TIP39/PTH2R signaling inhibits chondrocyte proliferation.

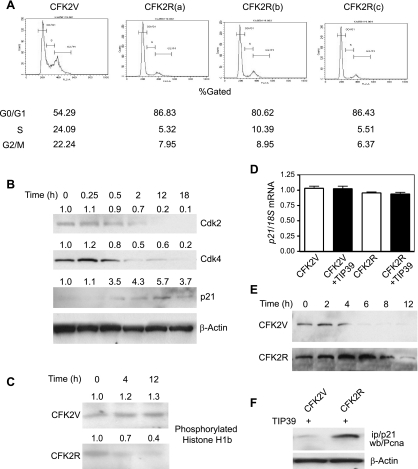

TIP39 restricts CFK2 cells at G0/G1 phase of cell cycle.

Since the rate of proliferation was decreased after TIP39 treatment, we next examined the pattern of distribution of cells in different phases of the cell cycle as a consequence of TIP39/PTH2R signaling. Three individual CFK2R clones were again used to study the effect of TIP39 on cell cycle progression. CFK2V and CFK2R cells were grown in culture and treated with TIP39, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed with a cell sorter. Without TIP39 treatment, there was no major difference in the number of CFK2V and CFK2R cells at various phases of the cell cycle (results not shown). On the other hand, a 1.6-fold increase in the number of cells at G0/G1 phase was observed for each of the three individual CFK2R clones on treatment with TIP39 (10−7 M) (Fig. 3A). A proportional decrease in the number of cells at S and G2/M phases was also evident. This observation indicated that TIP39/PTH2R signaling inhibits chondrocytic cell proliferation by restricting cells at G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle.

Fig. 3.

PTH2R signaling impairs cell cycle progression in CFK2R cells. A: %cells in various phases of the cell cycle were compared between vector-transfected and PTH2R-transfected CFK2 cells in the presence of TIP39; a, b, and c refer to the 3 CFK2R clones. B: time-dependent alteration in protein levels of Cdk2, Cdk4, and p21 due to TIP39/PTH2R signaling in CFK2R cells. β-Actin levels were used as control. Numbers indicate ratio of protein intensity over that of β-actin. At time 0, this ratio was assigned the value of 1. C: histone H1b phosphorylation in TIP39-treated CFK2 and CFK2R cells as a measure of Cdk2 functional activity. D: p21 mRNA levels were assessed in TIP39-treated and untreated CFK2V and CFK2R clones by real-time PCR. To standardize the quantification, 18S mRNA was amplified simultaneously. Experiments were performed with 3 different CFK2R clones (a, b, and c; only clone a is shown), with similar results. Data are means ± SE (n = 3) from 1 experiment repeated 3 times. E: stability of p21 was analyzed with a cycloheximide-treated pulse chase experiment in vector control and PTH2R-transfected CFK2 cells after TIP39 treatment. F: relative levels of p21 were analyzed by a coimmunoprecipitation experiment using proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) antibody. ip, Immunoprecipitation; wb, Western blot.

TIP39 alters levels of cell cycle regulators in CFK2R cells.

After observing that TIP39 treatment restricted CFK2R cells at G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle, we set out to determine the level of cell cycle-regulating genes in these cells. Both S phase-specific cyclin-dependent kinases (Cdk2 and Cdk4) decreased in CFK2R cells in a time-dependent fashion after TIP39 treatment (Fig. 3B). This is consistent with our observation that treated PTH2R-expressing cells failed to enter into S phase at a pace comparable to vector control cells. In contrast to the decrease of the cyclin-dependent kinases, p21 (Cip1), a Cdk2 inhibitor, was upregulated on TIP39 treatment in a time-dependent fashion (Fig. 3B). Hence, the dysregulation of cyclin-dependent kinases and their inhibitors contributed in part to the G0/G1 restriction of CFK2R cells following TIP39 treatment.

The functional aspect of this decrease in Cdk2 expression was assessed by measuring phosphorylation of histone H1b, a potent substrate for Cdk2 kinase activity (19). CFK2V and CFK2R cells were treated with TIP39 (10−7 M), and at the indicated time points Cdk2 was immunoprecipitated from lysates with a Cdk2-specific polyclonal antibody and the degree of functional Cdk2 activity was determined by measuring histone phosphorylation. The degree of phosphorylation remained virtually constant for control vector-transfected cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, a significant decrease (∼50%) in histone H1b phosphorylation was evident in CFK2R cells, even at 12 h of TIP39 treatment.

An increase in p21 protein level might arise because of transcriptional activation. To address this question, we treated CFK2V and CFK2R clones with TIP39, total RNA was isolated, and p21 transcript levels were determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR and verified with real-time PCR. We observed that the level of p21 transcripts remained virtually unaltered (Fig. 3D). This prompted us to examine whether the stability of protein, rather than increased transcription, was the cause of p21 accumulation. Cells were synchronized by serum starvation for 24 h and treated with cycloheximide. Treatment was terminated at different time points, and p21 levels were determined by Western blot analysis. In vector control cells, p21 decreased after 4 h (Fig. 3E). On the other hand, an appreciable amount of p21 could be detected even at 12 h after treatment in CFK2R cells, confirming the increased stability of the protein arising from TIP39/PTH2R signaling.

We next examined whether increased p21 levels bind and sequester proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a marker for proliferating cells, thereby hindering DNA replication. Serum-starved cells were released by the addition of serum and treated with TIP39 (10−7 M) for 18 h, p21 was immunoprecipitated from the total cell lysates, and immunocomplexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed for PCNA immunoreactivity by Western blotting. Compared with TIP39-treated CFK2V cells, significantly higher amounts of PCNA were precipitated from TIP39-treated PTH2R cells with equal amounts of initial total cell lysate (Fig. 3F). This further emphasized the functionality of the increased p21 levels in TIP39/PTH2R-mediated cell cycle arrest.

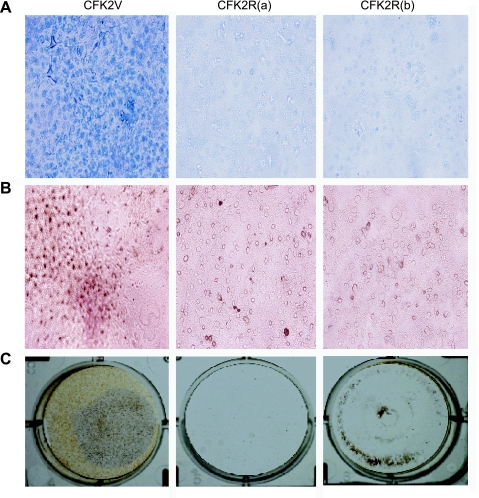

TIP39 treatment alters differentiation events in CFK2R cells.

We next sought to examine the effect of TIP39 on the chondrocytic differentiation process in CFK2R cells. Cells were grown in the presence of TIP39 (10−7 M) for 14 days and stained for proteoglycan expression, alkaline phosphatase activity, and mineralization. All three parameters of chondrocytic differentiation were reduced in PTH2R-expressing cells compared with vector control cells (Fig. 4). These findings indicated that TIP39/PTH2R signaling alters chondrocyte-differentiating events as well as proliferation. This is unlikely to simply be due to the decrease in proliferation, inasmuch as growth factors have been reported to reduce proliferation but increase differentiation in chondrocytes (26).

Fig. 4.

Chondrocyte differentiation is impaired by TIP39/PTH2R signaling. Proteoglycans (A), alkaline phosphatase activity (B), and mineralization (C) by von Kossa staining are shown for CFK2V cells and CFK2R clones a and b after treatment with TIP39 (10−7 M).

TIP39 alters expression profile of matrix proteins, cathepsins, and metalloproteinases in CFK2R cells.

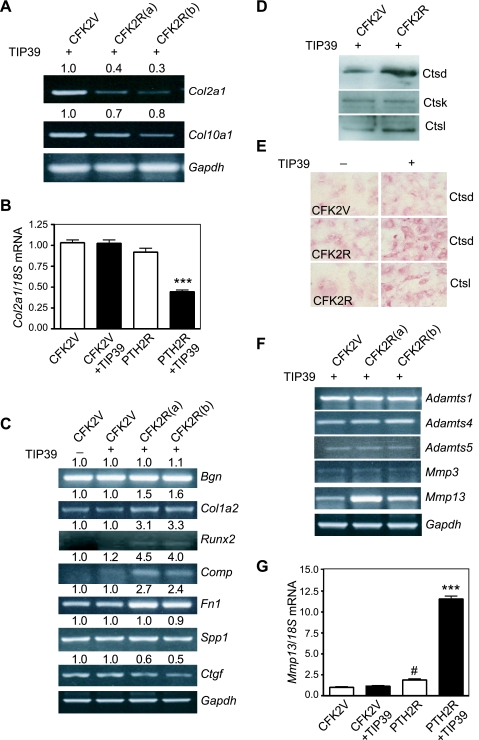

The observed alteration in differentiation arising from TIP39/PTH2R signaling prompted us to examine the expression profile of proteins that compose and modify the cartilaginous extracellular matrix. We first analyzed collagen type 2a1 (Col2a1), which is found primarily in cartilage and adds structure and strength to connective tissues, and collagen type X (Col10a1) expression in vector control and PTH2R-expressing cells. Indeed, Col2a1 expression was markedly reduced in TIP39-treated receptor-expressing cells compared with vector control (Fig. 5A). A less significant reduction in collagen type X was also observed, likely an associated event of the delayed differentiation process. The profound decrease in Col2a1 transcript levels arising after TIP39/PTH2R signaling was verified further by real-time PCR (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Altered expression of cartilaginous matrix proteins and metalloproteinases by TIP39/PTH2R signaling. A: relative abundance for Col2a1 and Col10a1 by semiquantitative RT-PCR. B: Col2a1 mRNA levels were assessed in TIP39-treated and untreated CFK2V and CFK2R(a) clones by real-time PCR. To standardize the quantification, 18S mRNA was amplified simultaneously. Results representative of 3 experiments, means ± SE (n = 3), were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest for multiple comparisons. ***P < 0.001 compared with PTH2R untreated cells. C: transcripts for other matrix proteins (Bgn, Col1a2, Runx2, Comp, Fn1, Spp1, and Ctgf) were determined by semiquantitative RT-PCR in CFK2V cells and 2 independent CFK2R clones (a and b) after TIP39 treatment. Numbers indicate the ratio of transcript over Gapdh and are the average of 2 or 3 experiments. At time 0, this ratio was assigned the value of 1. D: cathepsin D (Ctsd), cathepsin K (Ctsk), and cathepsin L (Ctsl) were analyzed by Western blotting in extracts from CFK2V and CFK2R cells. E: Ctsd and Ctsl immunocytochemical staining increased after treatment of CFK2R cells with TIP39. F: transcripts for metalloproteinases including Mmp13 were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR after TIP39 treatment. Numbers indicate the ratio of transcript over Gapdh and are the average of 3 experiments. G: Mmp13 transcript levels in TIP39-treated and untreated CFK2V and CFK2R(a) clones by real-time PCR. 18S mRNA was amplified simultaneously to standardize the quantification. Results representative of 3 experiments, means ± SE (n = 3), were analyzed by 1-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni posttest for multiple comparisons. ***P < 0.001 compared with PTH2R untreated cells; #P < 0.05 compared with CFK2V cells.

Expression of matrix proteins such as biglycan (Bgn) and osteopontin (Spp1) remained unaltered between vector control and CFK2R cells on TIP39 treatment (Fig. 5C). On the other hand, cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (Comp), Runx2, fibronectin 1 (Fn1), and, to a more modest degree, collagen type I, α2 (Col1a2) increased while connective tissue growth factor (Ctgf) decreased in TIP39-treated CFK2R cells.

TIP39/PTH2R signaling also induced alterations in the expression of cartilage matrix-modifying proteins. Cathepsin D (Ctsd) and cathepsin L (Ctsl) mRNA (not shown) and protein expression in CFK2R cells increased significantly, while levels of cathepsin K (Ctsk) remained unchanged (Fig. 5, D and E). In addition, the pattern of mRNA expression for a number of neutral metalloproteinases was examined. As shown in Fig. 5F, levels of peptidases generally associated with differentiating chondrocyte function such as Mmp3 and Adamts1, Adamts4, and Adamts5 did not show any alteration. On the other hand, Mmp13 expression was greatly increased (12-fold) in PTH2R-expressing clonal cell lines compared with vector-transfected cells when treated with TIP39. This observation was then verified by real-time PCR. Indeed, cells expressing the receptor exhibited a twofold increase in Mmp13 mRNA levels compared with vector cells, consistent with endogenous TIP39 expression in these cells. Moreover, activation of the receptor by the addition of TIP39 resulted in a 12-fold increase in Mmp13 transcripts in these cells (Fig. 5G).

These findings illustrate the capacity of the TIP39/PTH2R signaling pathway to alter the expression pattern of genes involved in the differentiation of chondrocytes and those that compose and modify the cartilaginous extracellular matrix.

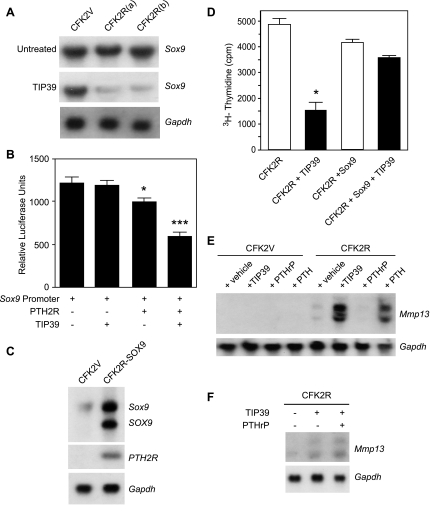

TIP39 markedly abrogates Sox9 expression in CFK2R cells.

Collagen type II is a direct transcriptional target of SOX9, the master transcriptional regulator of chondrogenesis (42). Our previous studies (30) showed that SOX9 regulates cell cycle and differentiation genes in CFK2 cells. Here we set out to investigate the effect of TIP39/PTH2R on Sox9 expression. Northern blot analysis of total RNA from CFK2V cells showed that without TIP39 treatment the levels of Sox9 transcript remained virtually unchanged (Fig. 6A). On the other hand, the levels were significantly reduced in TIP39 treated CFK2R cells.

Fig. 6.

TIP39/PTH2R signaling suppresses Sox9 expression. A: Sox9 mRNA in TIP39-treated and untreated CFK2V cells and 2 independent CFK2R clones (a and b) was analyzed by Northern blot analysis. B: Sox9 promoter activity as measured by a luciferase-based assay system using pGL3 basic luciferase reporter vector containing 450 bp of the mouse Sox9 promoter. The reporter construct was cotransfected with PTH2R into ATDC5 chondrocytes treated with or without TIP39 (10−7 M). Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.01 relative to reporter construct-transfected, PTH2R-negative, TIP39 untreated cells (n = 3). C: Northern blot analysis of coexpression of PTH2R and human SOX9 in CFK2 cells (CFK2R-SOX9). The increased expression of endogenous Sox9 relates to the ability of SOX9 to self-reinforce and help maintain its own expression (32). D: concurrent Sox9 expression in CFK2R cells prevents the observed decrease in [3H]thymidine incorporation following TIP39 (10−7 M) treatment. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, relative to untreated CFK2R cells (n = 3). E: Northern blot analysis showing that Mmp13 expression in CFK2R cells is not altered by PTHrP(1–36) (10−7 M) but is increased by the addition of TIP39 (10−7 M) or PTH(1–34) (10−7 M). F: Northern blot analysis showing that addition of PTHrP(1–36) (10−7 M) does not alter TIP39-induced Mmp13 expression in CFK2R cells. Experiments for E and F were repeated at least 3 times, with similar results.

To address whether TIP39/PTH2R signaling regulates Sox9 gene transcription, we proceeded to investigate the effect of this signaling system on Sox9 promoter activity. In view of the low transfection efficiency of CFK2 cells, we opted to use ATDC5 chondrocytes (34a) for these studies. ATDC5 chondrocytes were transiently transfected with a Sox9 promoter-luciferase reporter construct either alone or with PTH2R cDNA and cultured in the presence or absence of TIP39 (10−7 M) in the medium, and luciferase reporter activity was measured. In PTH2R-expressing cells, a significant reduction in luciferase activity was observed, again likely due to low endogenous TIP39 expression. This reduction was even more pronounced after activation of PTH2R by the addition of exogenous TIP39, indicating that the TIP39/PTH2R signaling pathway decreases Sox9 expression at the transcriptional level (Fig. 6B).

If regulation of Sox9 levels is critical for mediating the TIP39/PTH2R effects in these cells, then forced overexpression of Sox9 should avert them. Indeed, coexpression of SOX9 in CFK2R cells (Fig. 6C) prevented the observed decrease in [3H]thymidine incorporation in CFK2R cells following TIP39 treatment (Fig. 6D). These findings provide evidence that Sox9 expression is a key target for the TIP39/PTH2R signaling system in CFK2 chondrocytic cells.

Finally, the question arises of whether there is interplay between the PTH-PTHrP/PTH1R and TIP39/PTH2R signaling systems in this in vitro system, since CFK2 cells express endogenous PTH1R (3). Using Mmp13 expression as a readout marker of TIP39/PTH2R signaling, we examined the effectiveness of exogenous PTHrP(1–36) and PTH(1–34) to alter it. While none of the three ligands was capable of inducing Mmp13 expression in CFK2V cells, both TIP39 and PTH(1–34) had the capacity to do so in cells expressing PTH2R, while PTHrP(1–36) was totally ineffective (Fig. 6E). Moreover, PTHrP(1–36) failed to alter the response of the cells to exogenous TIP39 when both ligands were added simultaneously (Fig. 6F). These findings illustrate that the observed changes in Mmp13 expression arise specifically from signaling by PTH2R, with no interference from ligands specific for PTH1R.

DISCUSSION

In the present work we have demonstrated the in situ expression of TIP39/PTH2R signaling pathway in the growth plate of long bones and examined its functional relevance in endochondral bone biology, using the CFK2 in vitro cell culture system. We report that both TIP39 and PTH2R are expressed in growth plate cartilage, with PTH2R protein being synthesized by chondrocytes in the resting/early proliferating zone whereas TIP39 is expressed by chondrocytes in prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones. In contrast, PTHrP is synthesized mainly by chondrocytes in the early proliferating zone (1, 21), while PTH1R expression is concentrated in the prehypertrophic transition zone (23). Thus the sites of expression of TIP39 and PTH2R are diametrically opposite to those of PTH1R and PTHrP. Although TIP39 expression is in proximity to PTH1R, this ligand is unlikely to interact productively with this receptor and in fact may function as an antagonist (17). Similarly, PTH2R, although 51% identical to PTH1R, would likely respond very poorly or fail to respond at all to PTHrP (37) despite their close spatial proximity within the developing growth plate. This model was confirmed in our in vitro system using Mmp13 expression as a reporter system.

While PTHrP/PTH1R signaling is known to function in the maintenance of chondrocytes in a proliferative state and prevent hypertrophy, the consequences of TIP39/PTH2R activation in chondrocytes needed to be clarified. We undertook our studies in an in vitro system using CFK2 chondrocytic cells, which have been previously well characterized (3). We observed that, in contrast to PTHrP/PTH1R, TIP39/PTH2R signaling inhibited the proliferation of chondrocytes. Although transcriptional activation of SOX9 by phosphorylation was reported to be one of the main targets of PTHrP/PTH1R signaling (13), transcriptional downregulation of Sox9 expression was found to be the mediator of the antiproliferative effects of the TIP/PTH2R signaling system. Given our localization of PTH2R expression in relatively immature chondrocytes in situ and our in vitro data demonstrating antiproliferative effects, it would be reasonable to conclude that TIP39 emanating from the maturing and hypertrophic chondrocytes acts on the PTH2R localized in resting/early proliferating chondrocytes to reduce the rate at which resting chondrocytes enter the proliferative phase, and thus acts as a counteracting pathway to PTHrP/PTH1R actions in the cartilaginous growth plate.

Decreased transcription of Col2a1, a direct target of SOX9 (24, 25), and increased metalloproteinase expression, specifically MMP13, are pivotal events in the development of the secondary ossification site of the epiphyseal ends of the cartilaginous anlage (4). The highly restricted spatial distribution of the PTH2R that we observed in situ within the newborn growth plate, the decreased expression of Col2a1, and the increased expression of Mmp13 observed after TIP39/PTH2R activation in vitro are compatible with a role for this signaling system in the formation of the secondary ossification center. Further studies will be required, however, to verify this proposition.

Recently, familial early-onset generalized osteoarthritis in humans has been linked to chromosome 2q33.3, a region of linkage in which PTH2R resides (27). Furthermore, in one family a missense mutation (A225S) in PTH2R was identified and shown to cosegregate with the disease. Nevertheless, the mechanism of this observation is unknown. In our present studies we showed that by 8 wk PTH2R and TIP39 are expressed in articular chondrocytes in situ. MMP13, shown in our in vitro studies to be increased by the TIP39/PTH2R signaling system, has been reported to be overexpressed in chondrocytes of osteoarthritic cartilage (15, 28), and forced expression of constitutively active human MMP13 in hyaline cartilage induced osteoarthritis in postnatal mice (29). Cathepsin D and L, also shown to be increased in TIP39-treated CFK2R cells in our studies, have also been reported to be tightly associated with forms of osteoarthritis (2, 11, 34). Finally, COMP, which was also shown in the present studies to be increased by the TIP39/PTH2R signaling system, has been suggested as a useful prognostic marker of disease progression in knee and hip osteoarthritis (6, 14). Together, and within the limits of the use of the CFK2 model as representative of articular chondrocytes in vivo, these studies may indicate that overactivity of the TIP39/PTH2R signaling system in older animals can contribute to the complex pathophysiology of osteoarthritis. Whether enhanced PTH2R signaling arises from the mutant receptor identified in osteoarthritis is presently under active investigation.

Recently, inactivation of Tip39 was reported not to produce an obvious phenotype apart from sterility (40) and fear- and anxiety-related behavior (8) in Tip39−/− progeny. It remains to be seen whether a more thorough examination of these mice or the generation and analysis of Pth2r-null animals, which could have a more severe phenotype, may provide in vivo clues as to the importance of TIP39/PTH2R signaling in endochondral bone development and articular cartilage pathophysiology.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) (D. Goltzman and A. C. Karaplis) and National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-11794, project IV (H. Jüppner). A. C. Karaplis is recipient of a Bourse de Chercheurs Nationaux from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank J. S. Mort, Shriners Hospital for Children, Montreal, for providing the cathepsin antibodies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amizuka N, Warshawsky H, Henderson JE, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Parathyroid hormone-related peptide-depleted mice show abnormal epiphyseal cartilage development and altered endochondral bone formation. J Cell Biol 126: 1611–1623, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ariga K, Yonenobu K, Nakase T, Kaneko M, Okuda S, Uchiyama Y, Yoshikawa H. Localization of cathepsins D, K, and L in degenerated human intervertebral discs. Spine 26: 2666–2672, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernier SM, Goltzman D. Regulation of expression of the chondrocytic phenotype in a skeletal cell line (CFK2) in vitro. J Bone Miner Res 8: 475–484, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumer MJ, Longato S, Fritsch H. Structure, formation and role of cartilage canals in the developing bone. Ann Anat 190: 305–315, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen MM., Jr The new bone biology: pathologic, molecular, and clinical correlates. Am J Med Genet A 140: 2646–2706, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conrozier T, Saxne T, Fan CS, Mathieu P, Tron AM, Heinegard D, Vignon E. Serum concentrations of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein and bone sialoprotein in hip osteoarthritis: a one year prospective study. Ann Rheum Dis 57: 527–532, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fegley DB, Holmes A, Riordan T, Faber CA, Weiss JR, Ma S, Batkai S, Pacher P, Dobolyi A, Murphy A, Sleeman MW, Usdin TB. Increased fear- and stress-related anxiety-like behavior in mice lacking tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues. Genes Brain Behav 7: 933–942, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gensure RC, Gardella TJ, Juppner H. Parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide, and their receptors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 328: 666–678, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo J, Chung UI, Yang D, Karsenty G, Bringhurst FR, Kronenberg HM. PTH/PTHrP receptor delays chondrocyte hypertrophy via both Runx2-dependent and -independent pathways. Dev Biol 292: 116–128, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handley CJ, Mok MT, Ilic MZ, Adcocks C, Buttle DJ, Robinson HC. Cathepsin D cleaves aggrecan at unique sites within the interglobular domain and chondroitin sulfate attachment regions that are also cleaved when cartilage is maintained at acid pH. Matrix Biol 20: 543–553, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henderson JE, He B, Goltzman D, Karaplis AC. Constitutive expression of parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) stimulates growth and inhibits differentiation of CFK2 chondrocytes. J Cell Physiol 169: 33–41, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang W, Chung UI, Kronenberg HM, de Crombrugghe B. The chondrogenic transcription factor Sox9 is a target of signaling by the parathyroid hormone-related peptide in the growth plate of endochondral bones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 160–165, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hunter DJ, Li J, LaValley M, Bauer DC, Nevitt M, DeGroot J, Poole R, Eyre D, Guermazi A, Gale D, Felson DT. Cartilage markers and their association with cartilage loss on magnetic resonance imaging in knee osteoarthritis: the Boston Osteoarthritis Knee Study. Arthritis Res Ther 9: R108, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inada M, Wang Y, Byrne MH, Rahman MU, Miyaura C, Lopez-Otin C, Krane SM. Critical roles for collagenase-3 (Mmp13) in development of growth plate cartilage and in endochondral ossification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 17192–17197, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobert AS, Zhang P, Couvineau A, Bonaventure J, Roume J, Le Merrer M, Silve C. Absence of functional receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide in Blomstrand chondrodysplasia. J Clin Invest 102: 34–40, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonsson KB, John MR, Gensure RC, Gardella TJ, Juppner H. Tuberoinfundibular peptide 39 binds to the parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor, but functions as an antagonist. Endocrinology 142: 704–709, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karaplis AC, He B, Nguyen MT, Young ID, Semeraro D, Ozawa H, Amizuka N. Inactivating mutation in the human parathyroid hormone receptor type 1 gene in Blomstrand chondrodysplasia. Endocrinology 139: 5255–5258, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karaplis AC, Luz A, Glowacki J, Bronson RT, Tybulewicz VL, Kronenberg HM, Mulligan RC. Lethal skeletal dysplasia from targeted disruption of the parathyroid hormone-related peptide gene. Genes Dev 8: 277–289, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kronenberg HM. Developmental regulation of the growth plate. Nature 423: 332–336, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kronenberg HM. PTHrP and skeletal development. Ann NY Acad Sci 1068: 1–13, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanske B, Karaplis AC, Lee K, Luz A, Vortkamp A, Pirro A, Karperien M, Defize LH, Ho C, Mulligan RC, Abou-Samra AB, Juppner H, Segre GV, Kronenberg HM. PTH/PTHrP receptor in early development and Indian hedgehog-regulated bone growth. Science 273: 663–666, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee K, Deeds JD, Bond AT, Juppner H, Abou-Samra AB, Segre GV. In situ localization of PTH/PTHrP receptor mRNA in the bone of fetal and young rats. Bone 14: 341–345, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefebvre V, de Crombrugghe B. Toward understanding SOX9 function in chondrocyte differentiation. Matrix Biol 16: 529–540, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lefebvre V, Huang W, Harley VR, Goodfellow PN, de Crombrugghe B. SOX9 is a potent activator of the chondrocyte-specific enhancer of the pro alpha1(II) collagen gene. Mol Cell Biol 17: 2336–2346, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maeda A, Nishida T, Aoyama E, Kubota S, Lyons KM, Kuboki T, Takigawa M. CCN family 2/connective tissue growth factor modulates BMP signalling as a signal conductor, which action regulates the proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes. J Biochem (Tokyo) 145: 207–216, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meulenbelt I, Min JL, van Duijn CM, Kloppenburg M, Breedveld FC, Slagboom PE. Strong linkage on 2q33.3 to familial early-onset generalized osteoarthritis and a consideration of two positional candidate genes. Eur J Hum Genet 14: 1280–1287, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy G, Knauper V, Atkinson S, Butler G, English W, Hutton M, Stracke J, Clark I. Matrix metalloproteinases in arthritic disease. Arthritis Res 4, Suppl 3: S39–S49, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuhold LA, Killar L, Zhao W, Sung ML, Warner L, Kulik J, Turner J, Wu W, Billinghurst C, Meijers T, Poole AR, Babij P, DeGennaro LJ. Postnatal expression in hyaline cartilage of constitutively active human collagenase-3 (MMP-13) induces osteoarthritis in mice. J Clin Invest 107: 35–44, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panda DK, Miao D, Lefebvre V, Hendy GN, Goltzman D. The transcription factor SOX9 regulates cell cycle and differentiation genes in chondrocytic CFK2 cells. J Biol Chem 276: 41229–41236, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schipani E, Kruse K, Juppner H. A constitutively active mutant PTH-PTHrP receptor in Jansen-type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. Science 268: 98–100, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sekido R, Lovell-Badge R. Sex determination involves synergistic action of SRY and SF1 on a specific Sox9 enhancer. Nature 453: 930–934, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Servant MJ, Coulombe P, Turgeon B, Meloche S. Differential regulation of p27(Kip1) expression by mitogenic and hypertrophic factors: involvement of transcriptional and posttranscriptional mechanisms. J Cell Biol 148: 543–556, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sharif M, Saxne T, Shepstone L, Kirwan JR, Elson CJ, Heinegard D, Dieppe PA. Relationship between serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels and disease progression in osteoarthritis of the knee joint. Br J Rheumatol 34: 306–310, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34a.Shukunami C, Shigeno C, Atsumi T, Ishizeki K, Suzuki F, Hiraki Y. Chondrogenic differentiation of clonal mouse embryonic cell line ATDC5 in vitro: differentiation-dependent gene expression of parathyroid hormone (PTH)/PTH-related peptide receptor. J Cell Biol 133: 457–468, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Turner PR, Mefford S, Bambino T, Nissenson RA. Transmembrane residues together with the amino terminus limit the response of the parathyroid hormone (PTH)2 receptor to PTH-related peptide. J Biol Chem 273: 3830–3837, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Usdin TB, Bonner TI, Harta G, Mezey E. Distribution of parathyroid hormone-2 receptor messenger ribonucleic acid in rat. Endocrinology 137: 4285–4297, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Usdin TB, Gruber C, Bonner TI. Identification and functional expression of a receptor selectively recognizing parathyroid hormone, the PTH2 receptor. J Biol Chem 270: 15455–15458, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Usdin TB, Hilton J, Vertesi T, Harta G, Segre G, Mezey E. Distribution of the parathyroid hormone 2 receptor in rat: immunolocalization reveals expression by several endocrine cells. Endocrinology 140: 3363–3371, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Usdin TB, Hoare SR, Wang T, Mezey E, Kowalak JA. TIP39: a new neuropeptide and PTH2-receptor agonist from hypothalamus. Nat Neurosci 2: 941–943, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Usdin TB, Paciga M, Riordan T, Kuo J, Parmelee A, Petukova G, Camerini-Otero RD, Mezey E. Tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues is required for germ cell development. Endocrinology 149: 4292–4300, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Usdin TB, Wang T, Hoare SR, Mezey E, Palkovits M. New members of the parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone receptor family: the parathyroid hormone 2 receptor and tuberoinfundibular peptide of 39 residues. Front Neuroendocrinol 21: 349–383, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wright E, Hargrave MR, Christiansen J, Cooper L, Kun J, Evans T, Gangadharan U, Greenfield A, Koopman P. The Sry-related gene Sox9 is expressed during chondrogenesis in mouse embryos. Nat Genet 9: 15–20, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wysolmerski JJ, Stewart AF. The physiology of parathyroid hormone-related protein: an emerging role as a developmental factor. Annu Rev Physiol 60: 431–460, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]