Abstract

Vascular endothelial cells express the ligand-activated transcription factor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), which participates in the regulation of metabolism, cell proliferation, and inflammation. PPARγ ligands attenuate, whereas the loss of function mutations in PPARγ stimulate, endothelial dysfunction, suggesting that PPARγ may regulate vascular endothelial nitric oxide production. To explore the role of endothelial PPARγ in the regulation of vascular nitric oxide production in vivo, mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by an endothelial-specific promoter were crossed with mice carrying a floxed PPARγ gene to produce endothelial PPARγ null mice (ePPARγ−/−). When compared with littermate controls, ePPARγ−/− animals were hypertensive at baseline and demonstrated comparable increases in systolic blood pressure in response to angiotensin II infusion. When compared with those of control animals, aortic ring relaxation responses to acetylcholine were impaired, whereas relaxation responses to sodium nitroprusside were unaffected in ePPARγ−/− mice. Similarly, intact aortic segments from ePPARγ−/− mice released less nitric oxide than those from controls, whereas endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression was similar in control and ePPARγ−/− aortas. Reduced nitric oxide production in ePPARγ−/− aortas was associated with an increase in the parameters of oxidative stress in the blood and the activation of nuclear factor-κB in aortic homogenates. These findings demonstrate that endothelial PPARγ regulates vascular nitric oxide production and that the disruption of endothelial PPARγ contributes to endothelial dysfunction in vivo.

Keywords: endothelial nitric oxide synthase

the ligand-activated transcription factor, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ), is a member of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily. PPARγ is expressed in numerous cells and tissues including endothelial (34) and smooth muscle cells (30, 35) comprising the vascular wall. PPARγ is activated by a diverse spectrum of ligands including fatty acids and their derivatives and by synthetic ligands from the thiazolidinedione (TZD) class of medications such as rosiglitazone and pioglitazone. These drugs are widely employed in the treatment of type 2 diabetes where they enhance insulin sensitivity through the modulation of lipid metabolism in fat, liver, and skeletal muscle (19). In addition to insulin sensitization, TZD-mediated activation of PPARγ modulates inflammation as well as cell signaling and proliferation (54), suggesting that the activation of PPARγ in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells can modulate vascular function independent of insulin sensitization (17).

Consistent with this concept, TZDs have been reported to exert beneficial effects in experimental animal models of nondiabetic vascular disease (8, 10, 17, 31) and to reduce surrogate markers of vascular dysfunction in several clinical studies. TZD therapy in animal and human subjects improved endothelial function; reduced surrogate markers of vascular disease; improved flow-mediated, endothelium-dependent vasodilation; and reduced carotid intimal thickening and neointimal formation after coronary stent placement (1, 11, 13, 29, 39, 41, 52, 55). The vascular protective effects of TZDs have been reported in nondiabetic subjects with documented coronary disease (36, 49), cerebrovascular disease (38), or risk factors for atherosclerosis (7). In diabetic subjects, rosiglitazone may worsen (22, 44, 48), whereas pioglitazone reduced (15, 18, 33, 57), cardiovascular end points. Additional clinical trials will be required to further clarify the impact of TZD therapy on cardiovascular outcomes. Further clarification of the role of PPARγ in the regulation of vascular function will advance efforts to optimize the therapeutic potential of PPARγ activation in vascular disease.

While PPARγ stimulation appears to be vasoprotective, the disruption of PPARγ within the vascular wall may promote vascular dysfunction. Dominant negative mutations in human PPARγ are associated with hypertension and insulin resistance (3), conditions commonly associated with endothelial dysfunction. Emerging studies in genetically engineered mice have provided additional evidence for an important regulatory role of PPARγ in the vasculature. Although a global deletion of PPARγ results in embryonic lethality (2), PPARγ knockout mice that are rescued by preserving PPARγ expression in the trophoblast demonstrate a complex phenotype characterized by severe lipodystrophy, insulin resistance, and hypotension (16). In heterozygous mice with global dominant negative PPARγ expression, the cerebral vessels demonstrated endothelial dysfunction and an enhanced vascular remodeling that could be attenuated with superoxide inhibitors (4). Similarly, targeting dominant negative PPARγ expression to smooth muscle cells impaired nitric oxide (NO)-mediated vasodilation and caused systolic hypertension (21), whereas targeted interference with endothelial PPARγ led to enhanced endothelial dysfunction in response to high-fat diets (5). Similarly, endothelial PPARγ null (ePPARγ−/−) mice, created using the Cre-loxP system (42), were sensitized to the hypertensive effects of a high-fat diet, and treatment with rosiglitazone, while lowering blood pressure in control mice, did not lower blood pressure in ePPARγ−/− mice (43). These studies suggest that PPARγ plays a critical role in the regulation of normal vascular function and tone although the mechanisms for these effects remain to be defined.

NO, a critical endothelial-derived mediator, reduces vessel tone, platelet activation and aggregation, smooth muscle cell proliferation, and leukocyte adherence. Under pathophysiological conditions, the biological activity of NO is reduced. Previous in vitro studies demonstrated that the activation of PPARγ in vascular endothelial cells increased endothelial NO release (6, 9) by increasing the activity, but not the expression, of endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) through PPARγ-dependent mechanisms involving posttranslational eNOS regulation (46). PPARγ ligands also reduced superoxide generation in vascular endothelial cells by reducing the expression of selected subunits of the superoxide-generating enzyme NADPH oxidase in vitro (23) and in vivo (24). These studies suggest that PPARγ activation may coordinately regulate the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the vasculature by simultaneously increasing endothelial NO and reducing superoxide production, thereby restoring the “nitroso-redox” balance in the vasculature.

The current study extends previous reports to further clarify the role of endothelial PPARγ in normal vascular function in vivo. Our findings indicate that a disruption of endothelial PPARγ reduces NO production in the vascular wall and causes oxidative stress and vascular dysfunction. These findings emphasize the importance of endothelial PPARγ in the regulation of normal vascular function and suggest that this receptor may serve as a target for novel pharmacological approaches to improving endothelial dysfunction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of ePPARγ−/− mice.

All studies were performed according to protocols reviewed and approved by the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice from the C57Bl/6 strain with the loxP-flanked (floxed) PPARγ gene (Stock No. 004584: B6.129-Ppargtm2Rev/J) or with the Tie2-Cre transgene [Stock No. 004128: B6.Cg-Tg (Tie2-Cre) 12Flv/J] were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The floxed PPARγ mice were crossed with Tie2-Cre mice, and select offspring were bred together to generate ePPARγ−/− (PPARγ fl/fl; Cre+) and littermate control (PPARγ fl/fl; Cre−) mice. Care was taken to transmit the Cre transgene through the male germ line to avoid potential complexities involved in the transmission of Cre through the female germ line (12). More detailed genotyping methodology is provided in the online data supplement (note: all supplemental material can be found posted with the online version of this article). To confirm the expected Cre-mediated recombination in vascular endothelium, Tie2-Cre mice were bred with ROSA26 Cre reporter (R26R) mice that contain a recombination-activated lacZ transgene (50). Tissues from progeny generated by crossing R26R and Tie2-Cre mice were fixed in 0.2% glutaraldehyde and stained for β-galactosidase activity as previously described (53). Stained aortas were opened longitudinally for en face analysis or embedded in optimum cutting temperature compound (OCT, Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), sectioned perpendicular to the length of the vessel onto slides, counterstained with nuclear fast red (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), dehydrated in ethanol and xylene, and mounted for microscopic analysis.

In selected ePPARγ−/− mice, to confirm that the expression of the null PPARγ allele was limited to the vascular endothelium, the aortas were removed, cleaned, and cut into two sections of equal length. One half was opened longitudinally, and the endothelial surface was mechanically denuded, whereas the endothelium was left intact in the other half. DNA was then isolated from each aortic sample and subjected to PCR using primers spanning the deletion site in the PPARγ gene. PCR of the null PPARγ allele produced a ∼350-bp product. The resulting PCR products were separated on agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized on a UV light box.

Blood pressure monitoring and angiotensin II treatment.

Data Sciences International (St. Paul, MN) PA-C10 blood pressure probes were used for telemetric blood pressure monitoring as previously reported (28) (see online data supplement for experimental details). Blood pressures were monitored for 10 s each minute for two 24-h periods, and these results were analyzed by two-way ANOVA with repeated measures or averaged over that duration to obtain baseline hemodynamic data. In selected ePPARγ−/− and control animals, osmotic pumps (Alzet, Cupertino, CA) were implanted for subcutaneous infusion of angiotensin II (ANG II, 0.7 mg·kg−1·day−1, Sigma), an intervention previously shown to generate hypertension and endothelial dysfunction in the mouse (40). Hemodynamic data were then collected 4, 6, 8, and 10 days following the onset of ANG II infusion.

Measurement of endothelium-dependent and -independent vasorelaxation responses.

Isometric forces in aortic rings were measured as described previously (51). Aortic rings were threaded onto two triangular stainless steel wires and then mounted on hooks attached to a Harvard Apparatus (Holliston, MA) differential capacitor force transducer. The resting tension of each aortic ring was set to 40 mN and maintained throughout the experiment. Relaxation responses to graded concentrations of the endothelium-dependent vasodilator, acetylcholine, and to the endothelium-independent vasodilator, sodium nitroprusside, were determined in aortic rings contracted with l-phenylephrine. In selected studies, the relaxation responses of rings from littermate control and ePPARγ−/− mice were examined following an ex vivo treatment with rosiglitazone (10 μM for 1 h) or Tempol (1 mM for 30 min) in the muscle bath. Data were obtained using MP100W hardware and analyzed using AcqKnowledge software (Biopac, Goleta, CA).

Measurement of aortic NO production using electron spin resonance spectroscopy.

NO production was determined by incubating intact or denuded aortic segments with the NO spin trap, iron diethyldithiocarbamic acid [Fe(DETC)2] and electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy as reported (28). Detailed methods are provided in the online data supplement. The NO signal was derived from the amplitude of the peaks from the triplet ESR signal characteristic of the NO-Fe(DETC)2 complex. ESR signals were normalized to the amount of aortic protein in each sample.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay.

Nuclear proteins were isolated from the aortas of littermate control and ePPARγ−/− mice and subjected to electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis to examine the extent of NF-κB nuclear binding as previously reported (47) (see online data supplement for detailed methods).

Assays of oxidative stress in blood.

Serum was assayed for derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites (dROMs) by colorimetric assay, according to the manufacturer's protocol (Diacron International, Grosseto, Italy). Plasma cysteine (Cys) and cystine (CySS) levels, the major plasma small molecular weight thiol couple, were measured as an index of oxidative stress with HPLC and fluorescence detection as previously reported (25). Plasma redox potential (Eh) was calculated using the Nernst equation, Eh = Eo + RT/nF [ln (disulfide)/(thiol)2], where Eo is the respective standard potential for the redox couple at pH 7.4, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, n is 2 (the number of electrons transferred), and F is Faraday's constant. The standard potential for the Cys/CySS couple at pH 7.4 was −250 mV.

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analyses of mean arterial pressure (MAP), contractility, and glucose tolerance experiments were performed using two-way ANOVA with repeated measures and Bonferroni's posttest. A statistical analysis of NO levels by Fe(DETC)2 was performed using one-way ANOVA with Newman-Keuls posttest. Statistics on all other experiments were performed using an unpaired t-test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism v. 4.03 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

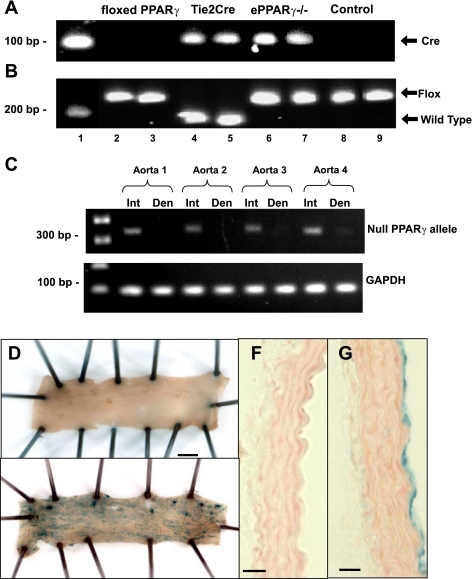

The ePPARγ−/− mice carry a Tie2-driven Cre gene identified by a 100-bp Cre PCR product (Fig. 1A) and two floxed PPARγ alleles identified by a 250-bp PPARγ PCR product (Fig. 1B). The specificity of Cre-recombinase expression in the vascular endothelium was supported by studies in Fig. 1C where the detection of the null PPARγ allele by PCR could be eliminated from aortas by a mechanical denudation of the endothelium. To further analyze Tie2-driven Cre recombinase expression, Tie2-Cre mice were bred with R26R mice, which express β-galactosidase activity only in tissues where Cre recombinase is expressed. A gross and microscopic examination of aortas from R26R+/−/Tie2-Cre−/− mice demonstrated no evidence of β-galactosidase activity (Fig. 1, D and F). In contrast, R26R+/−/Tie2-Cre+/− mice displayed intense β-galactosidase activity (blue staining) in the vascular endothelium but not in other cellular compartments of the vascular wall (Fig. 1, E and G). These findings suggest that vascular derangements resulting from Tie2-driven, Cre-mediated PPARγ depletion derive from PPARγ disruption of endothelial rather than nonendothelial compartments.

Fig. 1.

Genotyping of endothelial peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ) null (ePPARγ−/−) mice and specificity of Tie2-Cre expression. Mice carrying loxP sites flanking the PPARγ gene (floxed PPARγ) were bred with mice expressing Cre recombinase driven by the Tie2 promoter. Tail biopsies from founder pairs and progeny were analyzed by PCR for the presence of Cre recombinase (100 bp; A) and the floxed PPARγ allele (wild-type allele = 214 bp, and the floxed allele = 250 bp; B). Representative blots are shown. Lane 1, DNA ladder; lanes 2–5, founder pairs (lanes 2 and 3 = floxed PPARγ mice, and lanes 4 and 5 = Tie2-Cre mice); lanes 6–9, progeny (lanes 6 and 7 = ePPARγ−/− mice and lanes 8 and 9 = littermate control mice). C: aortas were removed from ePPARγ−/− mice, cleaned, and cut in half. One half of the aorta was cut longitudinally and the endothelial surface was mechanically denuded (Den), whereas the endothelium was left intact (Int) in the other half. DNA was isolated from each sample and subjected to PCR using primers that span the deletion site in the PPARγ gene. The null PPARγ allele produces a ∼350-bp product. The resulting PCR products were separated on agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide. Representative gels from 4 animals are presented. To examine Cre-mediated recombination in the vascular wall, Tie2-Cre mice were bred with ROSA26 reporter mice. Cre-positive progeny from this cross were euthanized, and their aortas were dissected, fixed, and examined for β-galactosidase (β-Gal) activity. Gross examination of the luminal surface of the aortas demonstrated lack of β-Gal staining in Cre-negative progeny (D), whereas examination of aortas from Cre-positive progeny demonstrated punctate β-Gal staining in a pattern consistent with endothelial labeling (E). Microscopic examination confirmed lack of β-Gal staining in all layers of the vascular wall in Cre-negative progeny (F), whereas examination of aortas from Cre-positive progeny demonstrated β-Gal staining in only the endothelial layer (G). Representative images from at least 3 animals are displayed. Scale bar in D and E = 1 mm. Magnification in F and G = ×40; scale bar = 100 μm.

As previously reported, ePPARγ−/− mice were viable, fertile, and normal in size compared with littermate control animals (supplemental Table 1) (43). Although the average body weights of ePPARγ−/− mice were ∼5% less than littermate controls, their fasting blood glucose levels and glucose tolerance tests were comparable with littermate controls (supplemental Table S1 and supplemental Fig. S2, respectively). A gross and microscopic analysis of the heart, liver, kidneys, lungs, and testicles revealed no differences between littermate control and ePPARγ−/− animals (supplemental Fig. S1, and data not shown). The organ weights were comparable between littermate control and ePPARγ−/− mice with the exception of the spleens that were significantly larger in ePPARγ−/− mice than in littermate controls (supplemental Table S1), consistent with a recent report demonstrating that Tie2-Cre-mediated PPARγ depletion caused splenic extramedullary hematopoiesis related to impaired osteoclast differentiation and reduced bone marrow medullary space (56). A hematological analysis of ePPARγ−/− mice also revealed a slight but significant reduction in hematocrit relative to littermate controls (supplemental Table S1).

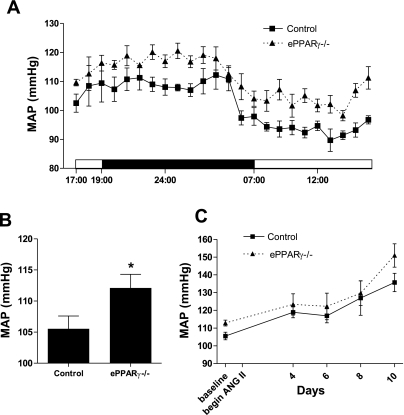

To examine arterial pressure, telemetric blood pressure monitors were surgically implanted into 8-wk-old ePPARγ−/− and littermate control mice. In contrast to a previous study examining blood pressure in this model using tail-cuff measurements (43), ePPARγ−/− mice displayed higher baseline MAPs compared with those of littermate control animals. The MAPs of ePPARγ−/− mice were consistently higher than those of littermate controls whether examined throughout the diurnal cycle (Fig. 2A) or averaged over a 24-h period (Fig. 2B). After the baseline MAPs were obtained, selected animals were challenged with ANG II (0.7 mg·kg−1·day−1 subcutaneously via osmotic pump), a vasoconstrictive stimulus known to induce endothelial dysfunction. As expected, ANG II infusion caused progressive increases in MAP in both littermate control and ePPARγ−/− mice. Consistent with the elevated baseline MAP in ePPARγ−/− mice, Fig. 2C illustrates that ePPARγ−/− mice also displayed higher MAP during ANG-II infusion compared with control mice (Fig. 2C) although this difference did not achieve a statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

Blood pressure in control and ePPARγ−/− mice. Telemetric blood pressure transmitters were surgically implanted into ePPARγ−/− or littermate control mice. Hemodynamic data were collected for 2 days, and baseline mean arterial pressures (MAPs) were calculated. A: MAP over a 24-h period. Each point represents mean MAP ± SE (in mmHg) from 11 control and 8 ePPARγ−/− mice. When compared with that of controls, the MAP of ePPARγ−/− mice was significantly higher. B: each bar represents average mean MAP ± SE over 24 h (in mmHg) from 11 control and 8 ePPARγ−/− mice. *P < 0.05 vs. control. C: after baseline blood pressure was measured, an osmotic minipump containing angiotensin II (ANG II) was implanted into selected mice from each group, and blood pressures were recorded 4, 6, 8, and 10 days following the onset of ANG II infusion. Each point represents the mean MAP ± SE (in mmHg) from 3 control and 5 ePPARγ−/− mice during ANG II infusion.

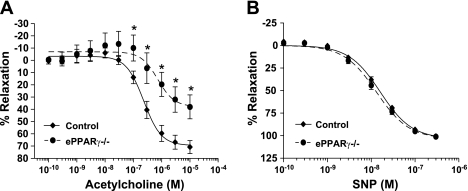

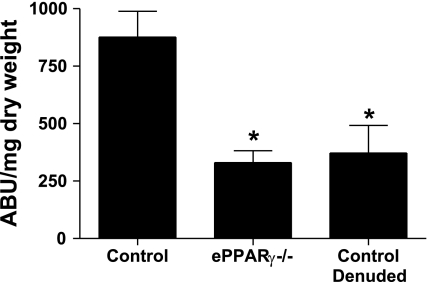

To explore whether endothelial PPARγ regulates vasorelaxation responses, aortic rings from ePPARγ−/− and littermate control animals were mounted onto force transducers for the determination of endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent vasorelaxation. The rings were first precontracted with l-phenylephrine to 80% maximal contraction. No difference was found in the sensitivity to l-phenylephrine-induced ring contraction between ePPARγ−/− and control animals (data not shown). As illustrated in Fig. 3A, when compared with those from littermate controls, aortic rings from ePPARγ−/− mice demonstrated an impaired endothelium-dependent, acetylcholine-stimulated vasorelaxation. Acetylcholine-mediated relaxation was fully inhibited in both control and ePPARγ−/− rings by a preincubation with the NO synthase inhibitor, NG-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, confirming that these acetylcholine-induced relaxations were NO dependent (data not shown). In addition, an acute addition of the PPARγ ligand, rosiglitazone, to the muscle bath of aortic rings from control and ePPARγ−/− animals failed to alter the relaxation responses (supplemental Fig. S3), consistent with the absence of acute nonspecific or nongenomic effects of PPARγ activation on vascular regulation. In contrast, relaxation responses to the endothelium-independent vasodilator, sodium nitroprusside, were comparable in ePPARγ−/− and littermate control vessels (Fig. 3B). Impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in ePPARγ−/− mice suggested a reduced NO bioavailability in these vessels. To further examine these findings, ePPARγ−/− and control aortas were removed and incubated with the NO spin trap, Fe(DETC)2, to directly measure vascular NO release from these vessels (14, 28). In aortas from selected control animals, the luminal surface of the vessel was exposed and gently rubbed to remove the endothelium to provide a negative control. When compared with those from littermate controls, aortas from ePPARγ−/− mice released significantly less NO (Fig. 4), approaching levels observed in denuded control vessels. However, reductions in NO production observed in vessels from ePPARγ−/− mice were not associated with significant reductions in the level of eNOS in the vascular wall (supplemental Fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in aortas from ePPARγ−/− mice. Freshly dissected aortic rings from ePPARγ−/− and littermate control mice were contracted with l-phenylephrine and then treated with increasing concentrations of acetylcholine (A) or sodium nitroprusside (SNP; B). Each symbol represents mean percent relaxation from 80% maximal contraction ± SE from 7–10 animals. *P < 0.05 vs. control vessels at same acetylcholine concentration.

Fig. 4.

Nitric oxide (NO) production is reduced in aortas from ePPARγ−/− mice. Aortas from ePPARγ−/− and littermate control mice were removed and subjected to measurements of NO production using electron spin resonance spectroscopy and the spin trap iron diethyldithiocarbamic acid. Denuded littermate control vessels (control denuded) served as a negative control. Each bar represents NO production as arbitrary units (ABU)/mg dry weight mean values ± SE from 7–15 individuals. *P < 0.01 vs. control.

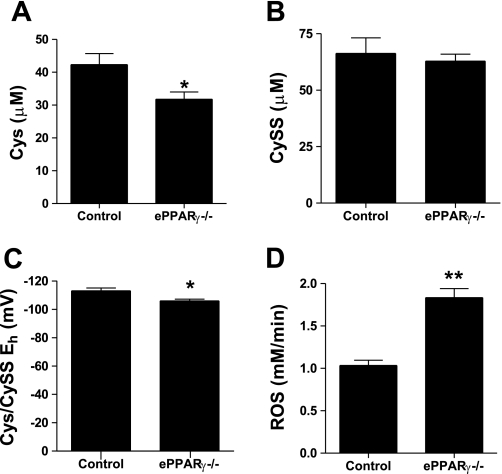

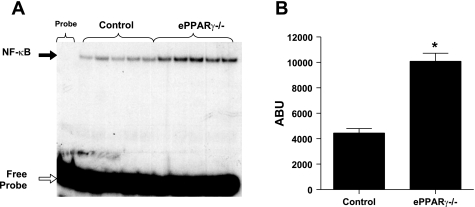

The absence of endothelial PPARγ also caused vascular oxidative stress. When compared with littermate controls, ePPARγ−/− mice had significant reductions in plasma levels of Cys, whereas CySS levels were unchanged, resulting in an increased plasma redox potential (Fig. 5, A–C). This index of oxidative stress was supported by higher levels of dROMs in ePPARγ−/− mice than in littermate controls (Fig. 5D). These markers of vascular oxidative stress were associated with evidence of an enhanced nuclear NF-κB binding activity in aortas from ePPARγ−/− compared with control aortas (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5.

Intravascular oxidative stress in ePPARγ−/− mice. A and B: mouse plasma concentrations of cysteine (Cys; A) and cystine (CySS; B). C: Cys/CySS redox potential. Each bar represents mean values ± SE from 6 individuals. D: serum samples were collected and assayed for derivatives of reactive oxygen metabolites. Each bar represents mean reactive oxygen species (in mM/min) ± SE from 7 to 8 mice. *P < 0.05 vs. control; **P < 0.0001 vs. control.

Fig. 6.

Aortas from ePPARγ−/− mice demonstrate enhanced nuclear NF-κB binding. Nuclear proteins were extracted from aortas of littermate control and ePPARγ−/− mice and then incubated with radiolabeled NF-κB oligonucleotide and subjected to electrophoretic mobility shift assay. DNA-protein complexes were separated on a native polyacrylamide gel (A: black arrow = probe shift due to NF-κB protein binding, and white arrow = unbound free probe). Densitometric analysis of bands in A was performed (B). Each bar represents mean ABU values ± SE from 5 samples. *P < 0.0001 vs. control.

DISCUSSION

Our laboratory recently reported that PPARγ ligands stimulated the production of NO by endothelial cells in vitro through PPARγ-dependent mechanisms involving an increase in the activity, but not the expression, of eNOS (46). In addition, PPARγ ligands inhibited endothelial cell superoxide production and expression of selected subunits of the superoxide-generating enzyme, NADPH oxidase (23), a critical mediator of endothelial dysfunction (32). These findings suggested that endothelial PPARγ might regulate a program of gene expression in the vascular wall that coordinately controls the production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species that participate in vascular function. The PPARγ ligand, rosiglitazone, also potently reduced vascular NADPH oxidase expression and superoxide production in vivo (24), providing additional evidence that PPARγ participates in the control of nitroso-redox balance in the vasculature.

The current study used a genetic approach to disrupt vascular endothelial PPARγ to further explore its role in the regulation of vascular function. Previously, ePPARγ−/− mice were not hypertensive at baseline but were more susceptible to hypertension induced by high-fat diets. Furthermore, the disruption of endothelial PPARγ abrogated the ability of rosiglitazone therapy to lower blood pressure in animals fed high-fat diets (43), suggesting that the direct activation of endothelial PPARγ played a critical role in mediating the vascular effects of PPARγ ligands. The current study extends these findings to demonstrate that a disruption of endothelial PPARγ has significant effects on blood pressure, vascular relaxation, NO production, oxidative stress, and inflammation without altering insulin sensitivity. Our findings using telemetry to measure MAP indicate that endothelial PPARγ disruption increased MAP at baseline.

In addition to causing basal hypertension, our findings provide conclusive evidence that endothelial PPARγ disruption caused significant vascular dysfunction characterized by impaired endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and reduced NO production. Using a similar Tie2-mediated PPARγ knockout model, a recent study (26) demonstrated that endothelium-dependent vasodilation in carotid arterial rings was impaired in ePPARγ−/− mice only after feeding with a high-fat diet. In contrast, our results demonstrate an impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation in aortic rings following feeding with standard chow diets. The precise explanation for these discrepancies remain to be defined but likely relate to methodological differences between the two studies including the vascular origin of the rings examined (aortic vs. carotid), the background strain of the mice, and subtle differences in the design of the floxed PPARγ gene between these two studies. Despite these discrepancies, both studies suggest that PPARγ plays a critical role in vascular homeostasis. Importantly, our studies provide direct measurements demonstrating that NO production was reduced in aortas from ePPARγ−/− mice and that these reductions were not associated with reduced eNOS expression. Our results not only provide in vivo support for previously described regulation of eNOS by PPARγ in endothelial cells in vitro (6, 9, 46) but further suggest that these reductions in vascular endothelial NO production may contribute to the enhanced oxidative stress in the vasculature and the induction of a proinflammatory state. Enhanced vascular oxidative stress in ePPARγ−/− animals manifested as increases in Cys:CySS redox and the formation of dROMs has previously been observed in other pathophysiological conditions associated with endothelial and vascular dysfunction and caused the activation of proinflammatory transcription factors such as NF-κB (20). Consistent with these reports, an enhanced activity of NF-κB was observed in the aortas of ePPARγ−/− mice. NO has been previously reported to inhibit NF-κB activation (27, 37, 45) and to mediate antioxidative effects (58), suggesting that the reductions in vascular NO production may have contributed to the observed vascular oxidative stress and NF-κB activation. These findings provide additional insights into the mechanisms involved in endothelial dysfunction resulting from global as well as smooth muscle- and endothelium- targeted dominant negative mutations in PPARγ (4, 5, 21). While our findings do not exclude the participation of additional mechanisms in the vascular dysfunction caused by endothelial PPARγ disruption, they emphasize the important relationship between endothelial PPARγ and vascular NO production.

Several limitations of these studies should be recognized. First, the Cre-lox approach employed to deplete endothelial PPARγ in the current model could induce compensatory alterations in the expression of other vasoregulatory pathways that modulate the phenotype of this animal. Future studies employing strategies that permit inducible endothelial PPARγ disruption may permit a more accurate assessment of the vascular impact of endothelial PPARγ disruption in the absence of, or before, the development of such compensatory processes. Second, Tie2-Cre expression caused an efficient disruption of PPARγ in hematopoietic tissues in addition to vascular endothelial cells (56). Therefore, the contributions of PPARγ disruption in bone marrow-derived cells to the vascular derangements reported in the current study cannot be fully excluded. However, the similarity of vascular derangements in the current study with those in cerebral resistance vessels caused by targeted PPARγ interference using the vascular endothelial cadherin promoter to mediate endothelial specificity (5) suggests that PPARγ expressed in the vascular endothelium plays a critical role in the maintenance of normal vascular endothelial function.

In summary, this study demonstrates that PPARγ is required for normal vascular NO production. The targeted disruption of PPARγ was sufficient to cause mild hypertension, impair aortic endothelium-dependent vasodilation and NO production, and generate vascular oxidative stress and the activation of a proinflammatory transcription factor in the vascular wall. These findings suggest that the disruption of endothelial PPARγ may contribute to vascular dysregulation in clinical conditions associated with endothelial dysfunction. This study also provides additional evidence supporting the link between PPARγ and the production of NO in the vasculature, suggesting that selective PPARγ modulators may provide a novel therapeutic approach to restoring vascular function in conditions associated with reduced NO bioavailability and endothelial dysfunction.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant DK-074518, the Veterans Affairs Medical Research Service, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals.

DISCLOSURES

Roy L. Sutliff and C. M. Hart received a research grant from Takeda Pharmaceuticals that was used in the development of the ePPARγ−/− mouse model.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- 1.Avena R, Mitchell ME, Nylen ES, Curry KM, Sidawy AN. Insulin action enhancement normalizes brachial artery vasoactivity in patients with peripheral vascular disease and occult diabetes. J Vasc Surg 28: 1024–1031, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell 4: 585–595, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barroso I, Gurnell M, Crowley VE, Agostini M, Schwabe JW, Soos MA, Maslen GL, Williams TD, Lewis H, Schafer AJ, Chatterjee VK, O'Rahilly S. Dominant negative mutations in human PPARgamma associated with severe insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Nature 402: 880–883, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyer AM, Baumbach GL, Halabi CM, Modrick ML, Lynch CM, Gerhold TD, Ghoneim SM, de Lange WJ, Keen HL, Tsai YS, Maeda N, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Interference with PPARgamma signaling causes cerebral vascular dysfunction, hypertrophy, and remodeling. Hypertension 51: 867–871, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beyer AM, de Lange WJ, Halabi CM, Modrick ML, Keen HL, Faraci FM, Sigmund CD. Endothelium-specific interference with peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma causes cerebral vascular dysfunction in response to a high-fat diet. Circ Res 103: 654–661, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calnek DS, Mazzella L, Roser S, Roman J, Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands increase release of nitric oxide from endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 52–57, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campia U, Matuskey LA, Panza JA. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activation with pioglitazone improves endothelium-dependent dilation in nondiabetic patients with major cardiovascular risk factors. Circulation 113: 867–875, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Z, Ishibashi S, Perrey S, Osuga J, Gotoda T, Kitamine T, Tamura Y, Okazaki H, Yahagi N, Iizuka Y, Shionoiri F, Ohashi K, Harada K, Shimano H, Nagai R, Yamada N. Troglitazone inhibits atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice: pleiotropic effects on CD36 expression and HDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 372–377, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho DH, Choi YJ, Jo SA, Jo I. Nitric oxide production and regulation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase phosphorylation by prolonged treatment with troglitazone: evidence for involvement of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma-dependent and PPARgamma-independent signaling pathways. J Biol Chem 279: 2499–2506, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collins AR, Meehan WP, Kintscher U, Jackson S, Wakino S, Noh G, Palinski W, Hsueh WA, Law RE. Troglitazone inhibits formation of early atherosclerotic lesions in diabetic and nondiabetic low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 21: 365–371, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cominacini L, Garbin U, Fratta Pasini A, Campagnola M, Davoli A, Foot E, Sighieri G, Sironi AM, Lo Cascio V, Ferrannini E. Troglitazone reduces LDL oxidation and lowers plasma E-selectin concentration in NIDDM patients. Diabetes 47: 130–133, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lange WJ, Halabi CM, Beyer AM, Sigmund CD. Germ line activation of the Tie2 and SMMHC promoters causes noncell-specific deletion of floxed alleles. Physiol Genomics 35: 1–4, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diep QN, El Mabrouk M, Cohn JS, Endemann D, Amiri F, Virdis A, Neves MF, Schiffrin EL. Structure, endothelial function, cell growth, and inflammation in blood vessels of angiotensin II-infused rats: role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma. Circulation 105: 2296–2302, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dikalov S, Fink B. ESR techniques for the detection of nitric oxide in vivo and in tissues. Methods Enzymol 396: 597–610, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, Erdmann E, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, Skene AM, Tan MH, Lefebvre PJ, Murray GD, Standl E, Wilcox RG, Wilhelmsen L, Betteridge J, Birkeland K, Golay A, Heine RJ, Koranyi L, Laakso M, Mokan M, Norkus A, Pirags V, Podar T, Scheen A, Scherbaum W, Schernthaner G, Schmitz O, Skrha J, Smith U, Taton J, PROactive investigators Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial in macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 366: 1279–1289, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duan SZ, Ivashchenko CY, Whitesall SE, D'Alecy LG, Duquaine DC, Brosius FC, 3rd, Gonzalez FJ, Vinson C, Pierre MA, Milstone DS, Mortensen RM. Hypotension, lipodystrophy, and insulin resistance in generalized PPARgamma-deficient mice rescued from embryonic lethality. J Clin Invest 117: 812–822, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duan SZ, Usher MG, Mortensen RM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma-mediated effects in the vasculature. Circ Res 102: 283–294, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Erdmann E, Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Massi-Benedetti M, Moules IK, Skene AM. The effect of pioglitazone on recurrent myocardial infarction in 2,445 patients with type 2 diabetes and previous myocardial infarction: results from the PROactive (PROactive 05) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 49: 1772–1780, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gervois P, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Drug Insight: mechanisms of action and therapeutic applications for agonists of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3: 145–156, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Go YM, Jones DP. Intracellular proatherogenic events and cell adhesion modulated by extracellular thiol/disulfide redox state. Circulation 111: 2973–2980, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halabi CM, Beyer AM, de Lange WJ, Keen HL, Baumbach GL, Faraci FM, Sigmund CD. Interference with PPAR gamma function in smooth muscle causes vascular dysfunction and hypertension. Cell Metab 7: 215–226, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Jones NP, Komajda M, McMurray JJ. Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes—an interim analysis. N Engl J Med 357: 28–38, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang J, Kleinhenz DJ, Lassegue B, Griendling KK, Dikalov S, Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligands regulate endothelial membrane superoxide production. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 288: C899–C905, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hwang J, Kleinhenz DJ, Rupnow HL, Campbell AG, Thule PM, Sutliff RL, Hart CM. The PPARgamma ligand, rosiglitazone, reduces vascular oxidative stress and NADPH oxidase expression in diabetic mice. Vascul Pharmacol 46: 456–462, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones DP, Mody VC, Jr, Carlson JL, Lynn MJ, Sternberg P., Jr Redox analysis of human plasma allows separation of pro-oxidant events of aging from decline in antioxidant defenses. Free Radic Biol Med 33: 1290–1300, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanda T, Brown JD, Orasanu G, Vogel S, Gonzalez FJ, Sartoretto J, Michel T, Plutzky J. PPARgamma in the endothelium regulates metabolic responses to high-fat diet in mice. J Clin Invest 119: 110–124, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsuyama K, Shichiri M, Marumo F, Hirata Y. NO inhibits cytokine-induced iNOS expression and NF-kappaB activation by interfering with phosphorylation and degradation of IkappaB-alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 18: 1796–1802, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinhenz DJ, Sutliff RL, Polikandriotis JA, Walp ER, Dikalov SI, Guidot DM, Hart CM. Chronic ethanol ingestion increases aortic endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in the rat. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 32: 148–154, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langenfeld MR, Forst T, Hohberg C, Kann P, Lubben G, Konrad T, Fullert SD, Sachara C, Pfutzner A. Pioglitazone decreases carotid intima-media thickness independently of glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from a controlled randomized study. Circulation 111: 2525–2531, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Law RE, Goetze S, Xi XP, Jackson S, Kawano Y, Demer L, Fishbein MC, Meehan WP, Hsueh WA. Expression and function of PPARgamma in rat and human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circulation 101: 1311–1318, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li AC, Brown KK, Silvestre MJ, Willson TM, Palinski W, Glass CK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands inhibit development of atherosclerosis in LDL receptor-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 106: 523–531, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R1014–R1030, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lincoff AM, Wolski K, Nicholls SJ, Nissen SE. Pioglitazone and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA 298: 1180–1188, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marx N, Bourcier T, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Plutzky J. PPARgamma activation in human endothelial cells increases plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 expression: PPARgamma as a potential mediator in vascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19: 546–551, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marx N, Schonbeck U, Lazar MA, Libby P, Plutzky J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activators inhibit gene expression and migration in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 83: 1097–1103, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marx N, Wohrle J, Nusser T, Walcher D, Rinker A, Hombach V, Koenig W, Hoher M. Pioglitazone reduces neointima volume after coronary stent implantation: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial in nondiabetic patients. Circulation 112: 2792–2798, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthews JR, Botting CH, Panico M, Morris HR, Hay RT. Inhibition of NF-kappaB DNA binding by nitric oxide. Nucleic Acids Res 24: 2236–2242, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meisner F, Walcher D, Gizard F, Kapfer X, Huber R, Noak A, Sunder-Plassmann L, Bach H, Haug C, Bachem M, Stojakovic T, Marz W, Hombach V, Koenig W, Staels B, Marx N. Effect of rosiglitazone treatment on plaque inflammation and collagen content in nondiabetic patients: data from a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 26: 845–850, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Minamikawa J, Tanaka S, Yamauchi M, Inoue D, Koshiyama H. Potent inhibitory effect of troglitazone on carotid arterial wall thickness in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83: 1818–1820, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mollnau H, Wendt M, Szocs K, Lassegue B, Schulz E, Oelze M, Li H, Bodenschatz M, August M, Kleschyov AL, Tsilimingas N, Walter U, Forstermann U, Meinertz T, Griendling K, Munzel T. Effects of angiotensin II infusion on the expression and function of NAD (P)H oxidase and components of nitric oxide/cGMP signaling. Circ Res 90: E58–E65, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Murakami T, Mizuno S, Ohsato K, Moriuchi I, Arai Y, Nio Y, Kaku B, Takahashi Y, Ohnaka M. Effects of troglitazone on frequency of coronary vasospastic-induced angina pectoris in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 84: 92–94, A98, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagy A. Cre recombinase: the universal reagent for genome tailoring. Genesis 26: 99–109, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicol CJ, Adachi M, Akiyama TE, Gonzalez FJ. PPARgamma in endothelial cells influences high fat diet-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertens 18: 549–556, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 356: 2457–2471, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng HB, Libby P, Liao JK. Induction and stabilization of I kappa B alpha by nitric oxide mediates inhibition of NF-kappa B. J Biol Chem 270: 14214–14219, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Polikandriotis JA, Mazzella LJ, Rupnow HL, Hart CM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligands stimulate endothelial nitric oxide production through distinct peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma-dependent mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25: 1810–1816, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ritzenthaler JD, Goldstein RH, Fine A, Smith BD. Regulation of the alpha 1(I) collagen promoter via a transforming growth factor-beta activation element. J Biol Chem 268: 13625–13631, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosen CJ. The rosiglitazone story—lessons from an FDA Advisory Committee meeting. N Engl J Med 357: 844–846, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sidhu JS, Kaposzta Z, Markus HS, Kaski JC. Effect of rosiglitazone on common carotid intima-media thickness progression in coronary artery disease patients without diabetes mellitus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 930–934, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 21: 70–71, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sutliff RL, Dikalov S, Weiss D, Parker J, Raidel S, Racine AK, Russ R, Haase CP, Taylor WR, Lewis W. Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors impair endothelium-dependent relaxation by increasing superoxide. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H2363–H2370, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takagi T, Akasaka T, Yamamuro A, Honda Y, Hozumi T, Morioka S, Yoshida K. Troglitazone reduces neointimal tissue proliferation after coronary stent implantation in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus: a serial intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol 36: 1529–1535, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Teng PI, Dichiara MR, Komuves LG, Abe K, Quertermous T, Topper JN. Inducible and selective transgene expression in murine vascular endothelium. Physiol Genomics 11: 99–107, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARgamma. Annu Rev Biochem 77: 289–312, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Walker AB, Chattington PD, Buckingham RE, Williams G. The thiazolidinedione rosiglitazone (BRL-49653) lowers blood pressure and protects against impairment of endothelial function in Zucker fatty rats. Diabetes 48: 1448–1453, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wan Y, Chong LW, Evans RM. PPAR-gamma regulates osteoclastogenesis in mice. Nat Med 13: 1496–1503, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wilcox R, Bousser MG, Betteridge DJ, Schernthaner G, Pirags V, Kupfer S, Dormandy J. Effects of pioglitazone in patients with type 2 diabetes with or without previous stroke: results from PROactive (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events 04). Stroke 38: 865–863, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wink DA, Miranda KM, Espey MG, Pluta RM, Hewett SJ, Colton C, Vitek M, Feelisch M, Grisham MB. Mechanisms of the antioxidant effects of nitric oxide. Antioxid Redox Signal 3: 203–213, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.