Abstract

Elastin fibers are predominantly composed of the secreted monomer tropoelastin. This protein assembly confers elasticity to all vertebrate elastic tissues including arteries, lung, skin, vocal folds, and elastic cartilage. In this study we examined the mechanism of cell interactions with recombinant human tropoelastin. Cell adhesion to human tropoelastin was divalent cation-dependent, and the inhibitory anti-integrin αVβ3 antibody LM609 inhibited cell spreading on tropoelastin, identifying integrin αVβ3 as the major fibroblast cell surface receptor for human tropoelastin. Cell adhesion was unaffected by lactose and heparin sulfate, indicating that the elastin-binding protein and cell surface glycosaminoglycans are not involved. The C-terminal GRKRK motif of tropoelastin can bind to cells in a divalent cation-dependent manner, identifying this as an integrin binding motif required for cell adhesion.

Cellular interactions with extracellular matrix proteins are vital for cell survival and tissue maintenance. The attachment of cells to their extracellular matrix (ECM)3 is often mediated by cell surface integrins. As such, integrins are involved in many biological functions such cell migration and proliferation, tissue organization, wound repair, development, and host immune responses. In addition to roles under normal physiological conditions, integrins are involved in the pathogenesis of diseases such as arthritis, cardiovascular disease, inflammation, microbial and parasitic infection, and cancer. Integrins are a family of heterodimeric transmembrane receptors containing one α subunit and one β subunit (1). Often integrins bind to ECM proteins via short RGD motifs within the matrix protein (2). In addition to an RGD motif, fibronectin also contains an upstream PHSRN synergy sequence, which is required for full integrin binding activity (3).

Elastin confers elasticity on all vertebrate elastic tissues including arteries, lung, skin, vocal fold, and elastic cartilage (4). Elastin comprises ∼90% of the elastic fiber and is intermingled with fibrillin-rich microfibrils (5). There is a single human tropoelastin gene in which alternative splicing can result in the loss of domains 22, 23, 24, 26A, 30, 32, and 33 (4). Elastin is made from the secreted monomer tropoelastin, which is a 60–72-kDa protein containing repeating hydrophobic and cross-linking domains. Hydrophobic domains are rich in GVGVP, GGVP, and GVGVAP repeats, which can associate by coacervation (6). This association results in structural changes and increased α-helical content (7). The cross-linking domains are lysine-rich. Occasionally these residues are modified to allysine through the activity of members of the family of lysyl oxidase (LOX) and four LOX-like enzymes. During coacervation the allysine and other allysines or specific lysine side chains come into close proximity, allowing nonenzymatic condensation reactions to occur, forming desmosine or isodesmosine cross-links (4). This process gives a highly stable cross-linked elastin matrix which has a half-life of ∼70 years. Members of the serine, aspartate, cysteine, and matrix metalloproteinase families of proteases can degrade elastin (8). The resulting elastin peptides have effects on ECM synthesis and cell attachment, migration, and proliferation (9).

The consequences of mutated or hemizygous elastin in the hereditary, connective tissue disorders cutis laxa, supravalvular aortic stenosis, and Williams-Beuren syndrome highlight the elastins essential role in elastic tissue function (10). Elastin is the major protein in large elastic blood vessels such as the aorta, where it is likely to inhibit the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells and so preventing vessel occlusion (11), which is a major cause of death in developed countries. Previous studies have shown that human and bovine tropoelastin can bind directly to a variety of cell types directly through a number of cell surface receptors (12–14) and also bind indirectly to cells through ECM proteins such as fibulin-5 (15, 16).

A mechanism by which elastin binds to cells is via the 67-kDa elastin-binding protein (EBP), which is a peripheral membrane splice variant of β-galactosidase. The EBP forms a complex with the integral membrane proteins carboxypeptidase A and sialidase, forming a transmembrane elastin receptor (12). The binding site for the EBP has been mapped to the consensus sequence XGXXPG within elastin and in particular to VGVAPG within exon 24 (17). The binding of elastin to the EBP results in cell morphological changes (18, 19), chemotaxis (20), decreased cell proliferation (21), and angiogenesis (22). Knockouts of β-galactosidase, which remove the EBP, display correctly deposited elastin (27). Additionally tropoelastin actively promotes cell adhesion, whereas VGVAPG does not. These observations imply that receptors other than EBP can interact with elastin.

Other studies have proposed a second mechanism involving the necessity of cell surface heparan and chondroitin sulfate-containing glycosaminoglycans for bovine chondrocyte interaction with bovine tropoelastin (14). Peptide binding analysis implicated the last 17 amino acids at the C terminus of bovine tropoelastin in this cell adhesive activity, with higher binding requiring the C-terminal 25 amino acids. This region is of interest, as in humans a mutation of Gly-773 to Asp in exon 33 results in blocked elastin network assembly and modulates cell binding to a peptide corresponding to exons 33 and 36 of human tropoelastin (28). Indeed Broekelmann et al. (14) have shown that synthetic peptides containing the C-terminal 29 amino acids of bovine tropoelastin possess cell adhesive activity; however, when the G773D mutation was incorporated into the peptide, it prevented cell adhesion to that peptide.

Although tropoelastin does not contain an RGD motif, other data identified a third mechanism involving direct interaction between integrin αvβ3 and human tropoelastin (13, 29). This interaction was also localized to the C-terminal domains of tropoelastin.

More recent data has shown that human umbilical vein endothelial cells can adhere to recombinant fragments of human tropoelastin (30, 31). In contrast to other data, regions encoded by the N-terminal exons (1–18), the central exons (18–27), and the C-terminal exons (18–36) all supported human umbilical vein endothelial cell attachment.

Although a previous study has shown a direct interaction between purified integrin αvβ3 and human tropoelastin (13), the integrin dependence of cell adhesion to tropoelastin had not been demonstrated. Here we demonstrate that human dermal fibroblasts adhere to recombinant human tropoelastin and that inhibitors of the elastin-binding protein and cell surface heparan sulfate have no effect on cell adhesion. In contrast, cell adhesion was dependent upon the presence of divalent cations, indicating integrin dependence. Inhibitory monoclonal antibodies identified integrin αVβ3 as the major receptor necessary for fibroblast adherence and spreading onto human tropoelastin. The binding motif for integrin-mediated cell adhesion is unknown; therefore, through the use of synthetic peptides, the adhesive activity was localized to the extreme C-terminal GRKRK motif of tropoelastin. This data present a novel mechanism for cell adhesion to human tropoelastin and identify a novel integrin binding motif within tropoelastin.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Recombinant human tropoelastin was produced in-house (32). Bovine elastin was sourced from Elastin Products Co. Human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) were sourced from the Coriell Research Institute (Camden, NJ). Anti-human integrin antibodies LM609 (αVβ3), 17E6 (αV), and JBS-5 (α5β1) were purchased from Chemicon. Peptide 36 (ACLGKACGRKRK), Peptide 36 short (ACLGKACG), and GRKRK were synthesized by AusPep. Unless stated, all other reagents were purchased from Sigma.

Cell Attachment Analysis

Cell attachment analysis was performed as described (33). To determine the degree of cell attachment, wells of a 96-well tissue culture plate were incubated in 100 μl of tropoelastin diluted to the appropriate concentration in PBS at room temperature for 1 h. Unbound tropoelastin was aspirated, and the samples were washed with 3 × 100 μl of PBS. Nonspecific polystyrene binding was blocked with 150 μl of 10 mg/ml heat-denatured (85 °C for 10 min then cooled on ice) bovine serum albumin (BSA) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Near confluent 75-cm2 flasks of HDFs were trypsinized by incubating with trypsin-EDTA at 37 °C for 4 min followed by neutralization with an equal volume of 10% FCS-containing media. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 800 × g for 3 min, and the cell pellet was resuspended in an appropriate volume of warm serum-free media. The cell density was counted and adjusted to 5 × 105 cells/ml. The BSA blocking solution was aspirated from the wells followed by 3 × 100-μl washes with PBS. 100-μl aliquots of cells were added to the wells then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 40 min. To estimate % cell attachment, 0, 10, 20, 30, 50, or 100 μl of cells made up to 100 μl with Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium was added to unblocked wells. After incubation, the cells in the known cell percentage wells were fixed with the addition of 10 μl of 50% glutaraldehyde (w/v). The cells were removed from the experimental wells, and non-adherent cells were removed with 2 × 100 μl of PBS washes. The adherent cells were fixed with the addition of 100 μl of 5% glutaraldehyde (w/v) in PBS for 20 min. The glutaraldehyde was removed, and wells were washed with 3 × 100 μl of PBS, then the cells were stained with 100 μl of 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet in 0.2 m MES, pH 5.0, for 1 h at room temperature. The crystal violet was aspirated, and excess stain was removed with 4 × 100-μl washes of distilled H2O. The crystal violet was solubilized in 100 μl of 10% (v/v) acetic acid, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader. Background crystal violet staining readings were subtracted from all experimental and known cell percentage results. The data from known cell percentage standards were plotted, and a linear regression was fitted. The gradient of the straight-line slope of the graph was used to convert experimental absorbances into percent attachment. In all experiments triplicate measurements were taken.

To determine the effect of divalent cations on HDF attachment, the same methodology was followed except that 50-μl aliquots of 2× concentration cation in PBS followed by 50 μl of HDFs resuspended in cation-free PBS to a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml was added to the samples after BSA blocking. To determine the effect of EDTA, lactose, heparan sulfate (Sigma), or synthetic peptide on HDF attachment, the same methodology was followed except that 50-μl aliquots of 2× concentration cation, lactose, heparan sulfate, EDTA, or peptide in serum-free media followed by 50 μl of HDFs resuspended in serum-free media to a density of 1 × 106 cells/ml was added to the samples after BSA blocking. Cell adhesion to peptides followed the same method except that the peptides were absorbed onto the tissue culture wells at room temperature overnight instead of 1 h.

Cell Spreading Analysis

Cell spreading was analyzed as described (33). To determine the degree of cell spreading, tissue culture plates were prepared as for cell attachment analysis. HDFs were trypsinized and quenched as for attachment analysis and resuspended to a density of 1 × 105 cells/ml. The BSA blocking solution was aspirated from the wells followed by 3 × 100-μl washes of PBS. 100-μl aliquots of cells were added to the wells then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 90 min. The cells were immediately fixed with the addition of 10 μl of 37% (w/v) formaldehyde directly to the well for 20 min. The formaldehyde was aspirated, and the wells were filled with PBS before layering a glass plate onto the plate. The level of cell spreading was determined by phase contrast (33). Cells were spread when the cell body was phase-dark with visible nuclei and the cytoplasm was visible around the entire nucleus, but not spread when rounded and phase-bright.

To determine the effect of anti-integrin antibodies on HDF spreading, the same methodology was followed except that 50-μl aliquots of 2× concentration antibody in serum-free media followed by 50 μl of HDFs resuspended in serum-free media to a density of 2 × 105 cells/ml was added to the wells after BSA blocking.

RESULTS

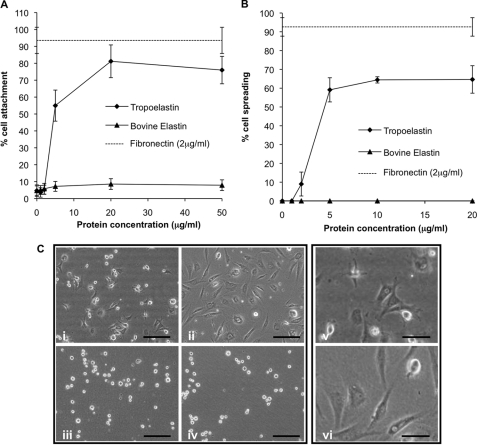

Recombinant Human Tropoelastin Supports Human Dermal Fibroblast Attachment and Spreading in a Dose-dependent Manner

Human dermal fibroblasts adhere to recombinant human tropoelastin in a dose-dependent manner with maximal attachment of 68% above BSA background levels observed at 20 μg/ml tropoelastin-coating concentration (Fig. 1A). No further attachment was promoted with coating concentrations up to 50 μg/ml. Human plasma fibronectin supported maximal attachment of 90% above background levels at a coating concentration of 2 μg/ml. Furthermore, although human recombinant tropoelastin could support cell adhesion, bovine-soluble elastin purified from neck ligament could not support cell adhesion above BSA background levels. In addition to supporting cell attachment, human recombinant tropoelastin could support up to 64% human dermal fibroblast spreading at a coating concentration of 5 μg/ml (Fig. 1B). No further spreading was observed at coating concentrations up to 20 μg/ml. Human plasma fibronectin supported 93% cell spreading at 2 μg/ml. Consistent with attachment analysis, bovine soluble elastin did not support human dermal fibroblast spreading. Phase contrast microscopy (Fig. 1C) showed that human dermal fibroblasts spreading onto recombinant human tropoelastin for 90 min are smaller and less flattened than those spreading onto plasma fibronectin. Cells spreading onto bovine elastin or BSA were completely rounded and phase-bright.

FIGURE 1.

A and B, human dermal fibroblast attachment (A) and spreading (B) to a concentration gradient of recombinant human tropoelastin (diamonds, solid line) and bovine soluble elastin (triangles, solid line). The dashed line indicates the % cell attachment or spreading onto the positive control, 2 μg/ml human plasma fibronectin. C, phase contrast photographs of human dermal fibroblast spreading onto 5 μg/ml recombinant human tropoelastin (i and v), 2 μg/ml human plasma fibronectin (ii and vi), 5 μg/ml bovine soluble elastin (iii), or BSA-blocked wells (iv) after incubation for 90 min. Scale bars on i–iv indicate 200 μm and on v and vi indicate 100 μm. All error bars indicate S.D. of triplicate measurements.

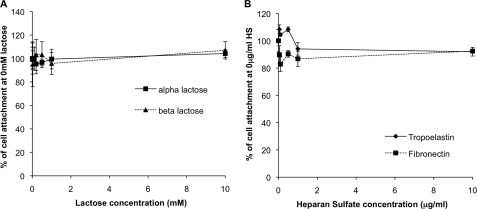

Human Dermal Fibroblast Attachment onto Recombinant Human Tropoelastin Is Independent of the Elastin-binding Protein and Heparan Sulfate

Previously lactose has been used to block cell adhesion to tropoelastin mediated via the elastin binding protein (12, 17). The inclusion of α- or β-lactose at concentrations up to 10 mm did not disrupt the adhesion of human dermal fibroblasts to human recombinant tropoelastin (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, soluble heparan sulfate has been used to block bovine fetal chondrocyte adhesion to bovine tropoelastin via cell surface glycosaminoglycans. Heparan sulfate inclusion at concentrations up to 10 μg/ml had no effect on human dermal fibroblast adhesion to human tropoelastin or plasma fibronectin (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

A, inhibition of human dermal fibroblast attachment onto 10 μg/ml recombinant human tropoelastin by α lactose (squares, solid line) or β lactose (triangles, dashed line). B, inhibition of human dermal fibroblast attachment onto 10 μg/ml recombinant human tropoelastin (diamonds, solid line) or 2 μg/ml human plasma fibronectin (squares, dashed line) using a concentration gradient of heparan sulfate (HS). Error bars indicate S.D. of triplicate measurements.

Previous reports have implicated these receptors in the cellular effects of elastin peptides (18–22) and for chondrocyte binding to bovine elastin (14). Our data indicate that human dermal fibroblast adhesion to recombinant human tropoelastin is not dominated by the elastin-binding protein or cell surface heparan sulfate.

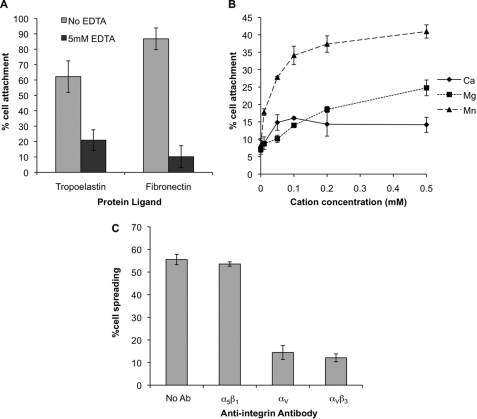

Integrin αVβ3 Mediates Human Dermal Fibroblast Attachment and Spreading onto Recombinant Human Tropoelastin

As integrin-ligand binding is cation-dependent, EDTA inhibition of human tropoelastin attachment was determined (Fig. 3A). Cell attachment to human recombinant tropoelastin or human plasma fibronectin was inhibited by the presence of 5 mm EDTA, indicating an integrin-dependent mechanism of attachment. To confirm the dependence on divalent cations, a concentration gradient of Ca2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ was added back to cation-free buffer, and the level of cell attachment was measured (Fig. 3B). Consistent with EDTA inhibition of cell adhesion, only background levels of cell adhesion were observed in the absence of cations. Mn2+ stimulated cell adhesion back to Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium buffer levels at a cation concentration of 0.5 mm. Mg2+ stimulated a lower level of cell adhesion than Mn2+, and Ca2+ only stimulated a low level of adhesion at cation concentrations up to 0.5 mm. These data implicate an integrin-mediated mechanism of cell adhesion to human tropoelastin. Previous solid phase studies using purified integrin αVβ3 had suggested that this integrin could bind directly to tropoelastin. Therefore, the integrin dependence of cell spreading was studied by including anti-integrin antibodies during cell spreading to human tropoelastin (Fig. 3C). The anti-αV integrin antibody 17E6 and the anti-αVβ3 antibody LM609 each inhibited cell spreading onto 10 μg/ml human tropoelastin, with the majority of cells being phase bright and rounded. An inhibitory anti α5β1 integrin antibody had no effect on cell spreading, controlling for a nonspecific antibody-specific response. LM609 also inhibited cell adhesion to human tropoelastin-coated wells (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

A, inhibition of human dermal fibroblast attachment to 10 μg/ml recombinant human tropoelastin or 2 μg/ml human plasma fibronectin in the presence (dark gray bars) or absence (light gray bars) of 5 mm EDTA. B, human dermal fibroblast attachment on to 10 μg/ml recombinant human tropoelastin in the presence of a concentration gradient of Ca2+ (diamonds), Mg2+ (squares), or Mn2+ (triangles). In additional studies, the degree of attachment in the presence of 0.5 mm Mn2+ was similar to that in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 49.5% for 0.5 mm Mn2+ and 48% for Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (data not shown). C, anti-integrin antibody (Ab) inhibition of human dermal fibroblast spreading onto 10 μg/ml recombinant human tropoelastin. Antibodies JBS-5 (anti α5β1), 17E6 (anti αV), and LM609 (anti αVβ3) were used at 20 μg/ml. Error bars indicate S.D. of triplicate measurements.

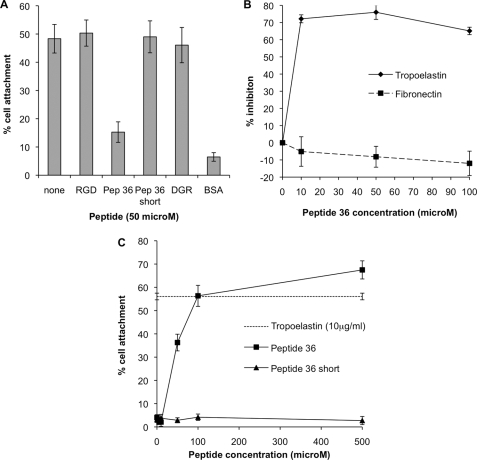

Adhesion of Human Dermal Fibroblasts to Tropoelastin Is via the C Terminus

Previous studies implicated the C terminus of tropoelastin in cell adherence. To determine whether this region was responsible for αVβ3-mediated fibroblast adhesion to human tropoelastin, synthetic peptides corresponding to the C-terminal 12 amino acids of exon 36 (Peptide 36 (ACLGKACGRKRK)) and a shortened peptide lacking the C-terminal four amino acids (Peptide 36 short (ACLGKACG)) were added to cells adhering to human tropoelastin (Fig. 4A). At a concentration of 50 μm Peptide 36 inhibited cell adhesion to near BSA background levels. Peptide 36 short, RGD, and the control peptide DGR had no effect on cell adhesion. To discount the possibility that Peptide 36 inhibition of cell adhesion to human tropoelastin was through a nonspecific mechanism, cell adherence to fibronectin and human tropoelastin in the presence of Peptide 36 was determined (Fig. 4B). Peptide 36 inhibited 73% of cell adhesion to human tropoelastin at a concentration of 10 μm, whereas no inhibition of fibronectin adherence was observed at Peptide 36 concentrations up to 100 μm. To determine whether this region was responsible for cell adhesion, not just inhibition of human tropoelastin binding, the percentage cell attachment to Peptide 36-coated wells was measured (Fig. 4C). Peptide 36 supported dose-dependent cell attachment with maximal 67% cell attachment at a coating concentration of 500 μm. Tropoelastin-coated wells supported 57% cell attachment. In contrast, Peptide 36 short did not support cell attachment at concentrations up to 500 μm. These data indicate that the C-terminal four amino acids of tropoelastin are part of a necessary cell adhesion motif.

FIGURE 4.

A, inhibition of human dermal fibroblast attachment to 10 μg/ml human recombinant tropoelastin with 50 μm RGD peptide, Peptide 36 (ACLGKACGRKRK), Peptide 36 Short (ACLGKACG), and the negative control DGR. B, dose-dependent inhibition of human dermal fibroblast attachment to 10 μg/ml human recombinant tropoelastin (diamonds, solid line) or 1 μg/ml human plasma fibronectin (squares, dashed line) with a concentration gradient of Peptide 36. Percentage inhibitions were calculated against cell adhesion to a non-blocked control. C, human dermal fibroblast attachment to wells coated with a concentration gradient of Peptide 36 (squares) or Peptide 36 Short (triangles). The percentage of cell attachment to wells coated with 10 μg/ml human recombinant tropoelastin is indicated with a dashed line. Error bars indicate S.D. of triplicate measurements.

The C-terminal GRKRK Motif of Tropoelastin Supports Integrin-mediated Cell Adhesion

To positively identify the C-terminal five amino acids as the cell binding motif within tropoelastin, we examined the cell adhesive properties of the synthetic peptide GRKRK. When added to cells adhering to human tropoelastin, GRKRK could inhibit adhesion to tropoelastin from 50% above BSA background levels in the absence of peptide to 16% in the presence of GRKRK (Fig. 5A). No effect on cell adhesion to tissue culture plastic was observed in the presence of GRKRK, controlling for a nonspecific activity of this peptide. To confirm the adhesive activity of this motif, the level of cell adhesion to GRKRK was measured. GRKRK could support 46% cell adhesion above BSA background levels at a peptide concentration of 250 μm (Fig. 5B). This indicates that this region is an adhesive motif in tropoelastin. To determine whether the adhesion to GRKRK was integrin-mediated, the cation dependence of attachment to GRKRK was analyzed. Inclusion of EDTA inhibited 77% of cell attachment to GRKRK and a similar 67% of adhesion to tropoelastin (Fig. 5C). Heparan sulfate inhibited 12% of cell adhesion to GRKRK and 8% of adhesion to tropoelastin. To further confirm the divalent cation dependence of cell adhesion to GRKRK, cell adhesion was measured in the presence of a dose of Ca2+, Mg2+, and Mn2+ (Fig. 5D). In the absence of cations GRKRK supported 5% cell adhesion. Mg2+ and Ca2+ did not promote cell adhesion to GRKRK. In contrast, Mn2+ promoted 58% cell adhesion to GRKRK above no cation controls at a concentration of 0.2 mm. These data indicate that indeed GRKRK is an integrin binding motif within tropoelastin.

FIGURE 5.

A, human dermal fibroblast attachment to wells coated with 10 μg/ml human recombinant tropoelastin then BSA blocked or to uncoated and unblocked tissue culture wells in the presence (black bars) or absence (gray bars) of 20 μm peptide GRKRK. B, human dermal fibroblast attachment to wells coated with 25 or 250 μm peptide GRKRK or 10 μg/ml human recombinant tropoelastin. C, EDTA inhibition of human dermal fibroblast adhesion to wells coated with 200 μm peptide GRKRK or 10 μg/ml human recombinant tropoelastin. Cell adhesion was measured in the presence of 5 mm EDTA (gray bars) or 10 μg/ml heparan sulfate (black bars). % inhibition was calculated against adhesion to a non-blocked control. D, human dermal fibroblast attachment in cation-free buffer in the presence of a concentration gradient of Ca2+ (diamonds), Mg2+ (squares), and Mn2+ (triangles) to wells coated with 200 μm peptide GRKRK. Error bars indicate S.D. of triplicate measurements.

DISCUSSION

Cellular interactions with extracellular matrix proteins give vital cues to the cell for cell survival and tissue maintenance. Although integrin αVβ3 has been shown to interact directly with tropoelastin by solid phase analysis, the utilization of this integrin by cells adhering to human tropoelastin has not been studied. As tropoelastin is the major constituent of elastic tissue and in vivo elastic fibers are associated with cells (30, 34), we have investigated the cell binding properties of human tropoelastin.

In these studies human skin fibroblasts were shown to be capable of attaching and spreading on recombinant human tropoelastin. The level of cell adhesion to human tropoelastin (68%) is consistent with the level of cell attachment observed on other elastic fiber proteins such as fibulin-5 (45% adhesion (35)) and fibrillin-rich microfibrils (35% adhesion (36)). Therefore, human tropoelastin is a truly cell adhesive protein.

Soluble bovine elastin was not capable of supporting adhesion or spreading. Others have shown that the C terminus of tropoelastin may be lost in mature elastic fibers, which would account for the lack of cell interaction to soluble bovine elastin (37).

A prior study using solid phase binding assays showed a direct interaction between purified integrin αvβ3 and the C-terminal exons of human tropoelastin (13); however, the importance of this integrin in cell-human tropoelastin adhesion has not been studied. The attachment of cells to the extracellular matrix is often mediated by cell surface integrins in a cation-dependent manner (38). We found that the presence of EDTA blocked fibroblast adhesion to human tropoelastin. In the absence of cations Mn2+ could restore cell binding, whereas Mg2+ and Ca2+ had lower efficacy. This pattern of cation dependence is indicative of integrin-mediated adhesion (38). Moreover, antibody LM609 and 17E6 inhibition of cell adherence identified integrin αvβ3 as the predominant receptor for human tropoelastin on human fibroblasts. These results show that integrin αvβ3 on cells can bind to tropoelastin. In contrast, others have shown no inhibition of chondrocyte adherence to tropoelastin using either EDTA or LM609. This may be because of cell lineage: i.e. bovine chondrocytes and Chinese hamster ovary cells compared with fibroblasts utilized.

The EBP, a previously identified tropoelastin receptor, binds to the sequence VGVAPG in exon 24 of tropoelastin and is inhibited by lactose (12, 17). In this study lactose did not inhibit cell binding, discounting the elastin-binding protein as the elastin receptor responsible for fibroblast adherence to human tropoelastin. This is consistent with reports of a lack of chondrocyte adherence observed on a fragment of tropoelastin encoded by exons 15–29, which contains VGVAPG (14). Furthermore, β-galactosidase (which is alternately spliced to give a component of the EBP) knockout in mice, which would knock out the EBP, does not affect elastin deposition, indicating that another receptor is capable of compensating for the EBP (27). In further support, peptides that contain VGVAPG are poorly adhesive but have potent chemotactic and signaling properties. As the EBP binding site possesses signaling rather than adhesive properties, these data indicate that adhesion and signaling activities of tropoelastin could be mediated by distinct receptors. Consistent with previous data (14), we observed no actin stress fiber assembly in cells adherent to human tropoelastin compared with cells adherent to plasma fibronectin (data not shown). Therefore, integrin engagement is necessary for cell adhesion to human tropoelastin but may not result in signaling into the cell necessary for cytoskeletal assembly.

Cell surface glycosaminoglycans and, in particular, heparan sulfate have also been shown to mediate bovine chondrocyte-bovine tropoelastin interactions. In this study when heparan sulfate was added to fibroblasts no inhibition of cell adhesion was observed. Furthermore, EDTA lifting of cells had no effect on the mechanism of cell-tropoelastin interaction compared with trypsin lifting of cells (supplemental figures). This excludes the possibility that during lifting trypsin might have removed a heparan sulfate-mediated tropoelastin receptor from the cell surface required for heparan sulfate-mediated cell adhesion to tropoelastin. Interestingly, although heparan sulfate-mediated cell adhesion to bovine tropoelastin was assigned to the C terminus of tropoelastin, this was not contained in exon 36, as a peptide corresponding to the last 14 amino acids of bovine tropoelastin was not capable of supporting cell adhesion. The minimum sequence for bovine tropoelastin adhesion required the last 3 amino acids of exon 35 in conjunction with exon 36 (i.e. C-terminal 17 amino acids), with higher binding requiring the last 11 amino acids of exon 35 in conjunction with exon 36 (i.e. C-terminal 25 amino acids) (14). Human tropoelastin does not contain the exons 34 and 35 that are involved in heparan sulfate-mediated adhesion; however, human exon 33 has been proposed to substitute for bovine exon 35 (28). This implies that the different mechanisms of human tropoelastin or bovine tropoelastin adhesion to cells may simply reflect differing cell lines utilized.

It has been postulated cell surface heparan sulfate-mediated cell adhesion may be through cell surface syndecans (14). Syndecans have been shown to cooperatively signal with integrins to assemble the cellular cytoskeleton (39). Interestingly, chondrocytes, which adhere to tropoelastin through cell surface glycosaminoglycans, but not integrins, have a predominance of filopodial extensions which are similar to those seen for syndecan-2 or -3 overexpressing cells. As we observed no heparan sulfate dependence on cell adhesion and attachment and also no actin cytoskeletal assembly, it may be possible that in our system we did not recruit syndecans. It is possible that individual sites on tropoelastin are capable of mediating cell-tropoelastin interactions by binding to either integrin αvβ3 or cell surface glycosaminoglycans, and usage of both sites may be required for full cytoskeletal assembly.

Others have previously reported cell adhesion to elastin through the bridging protein fibulin-5 (15, 16). In our adhesion assays the cells are incubated with the tropoelastin surface for 40 min, reducing the possibility of cell-derived proteins functioning as a bridging molecule between tropoelastin and cellular receptors. Furthermore, previous data (13) have shown a direct interaction between integrin αVβ3 and human tropoelastin. This was performed in the absence of cells on recombinantly expressed tropoelastin. Therefore, there were no other proteins in this assay system that could reasonably bridge between tropoelastin and integrin αVβ3. Interestingly the whole of the tropoelastin molecule has been shown to be necessary for fibulin-5-tropoelastin association (40), and so fibulin-5 should not associate with our cell adhesive peptide 36 and GRKRK. Therefore, it is unlikely that fibulin-5 will bind to this small section of tropoelastin, making it unlikely that fibulin-5 is acting as a bridging molecule for cell adhesion. In addition, potential bridging proteins associated with elastic fibers, namely fibrillin-1 (41), fibulin-5 (40), and MAGP-2 (42), bind to cells via RGD motifs (36, 35, 43). As we observed no inhibition of cell binding to human tropoelastin by RGD peptides, it is unlikely that these proteins act as bridging proteins between cells and human tropoelastin. Additionally, fibrillin-1 possesses dependence upon different integrin receptors to mediate cell binding than a predominance of integrin αVβ3 (36). The protein synthesis blocker, actinomycin D, had no inhibitory effect on cell adhesion to tropoelastin (supplemental figures), giving additional evidence that cells can interact directly with tropoelastin rather than through a cell-derived bridging protein. Therefore, we have shown a direct binding interaction between integrin αVβ3 and human tropoelastin (13), which we have now shown results in cell adhesion to tropoelastin.

In this study we have used synthetic peptides to map cell binding to the C-terminal 5 amino acids of exon 36. Furthermore, we have shown integrin-mediated cell adhesion to this motif, identifying GRKRK as a novel integrin binding motif. Indeed there is no classical RGD integrin recognition site in tropoelastin; however, not all integrin-receptor ligation is via RGD motifs. For example, Cyr61, fibrinogen, tumstatin, and the collagen α3(IV) NC1 domain do not bind via RGD motifs. Furthermore, integrin α1β1 recognizes the motif RKKH, which is very similar to the RKRK motif that we have identified as being necessary for cell interaction (44). Interestingly the RKRK motif is highly conserved between divergent species, indicating that it possesses a vital function.

Although we have identified integrin αVβ3 as a cellular receptor for human tropoelastin, the in vivo importance of this interaction is unknown. Integrins have been implicated in many biological functions such as cell migration and proliferation, tissue organization, and roles in the pathogenesis of disease.

Integrin αVβ3 could be involved in tropoelastin deposition onto maturing elastic fibers. This is consistent with the identified interaction with tropoelastin, i.e. the non-deposited, progenitor of elastin. Integrins are implicated in ECM assembly, including αVβ3 participation in fibronectin network deposition (45). However, the αVβ3 knock-out mouse has apparently functional elastic lamellae in blood vessels (46). Therefore, this receptor may not be solely responsible for elastic fiber deposition and assembly and may point to involvement of multiple tropoelastin receptors in elastogenesis.

In this study we have shown that cell adhesion is predominantly mediated through integrin αVβ3 and the C terminus of tropoelastin, which could implicate this integrin in elastin fiber assembly. Mutation G773D, which is present in exon 33, N-terminal to exon 36 in human tropoelastin, blocks cell binding but also prevents cellular deposition of elastin to form fiber-like structures, implicating cell adhesion in the assembly of tropoelastin fibers (28). Additionally, cutis laxa (the hyper-extensible elastic tissue disorder) mutations tend to cluster in exons 30, 32, and 33 and generally result in disruption or removal of exon 36 (24–26). These examples suggest that the C terminus is important in human elastic fiber assembly.

The migration of dermal fibroblasts in a wound environment model relies on integrin interactions that include αVβ3 (23). Similarly, integrin αVβ3-mediated cell-elastin interactions could be required to anchor cells to elastic fibers or to sense modifications of the elastic fiber network. However, it is possible that lysine(s) in the GRKRK motif may be subsequently cross-linked, making them unavailable for cell adherence in mature elastin. Others have reported a low level of C-terminal sequences in total soluble elastin; however, this utilized an antibody that detected the last 14 amino acids (37), whereas we find that the last 5 amino acids are important. Other data suggest that the mutant G773D, 2 amino acids upstream of exon 36, causes proteolysis of elastin, resulting in loss of the C terminus and loss of cell binding. Therefore, severe, early onset chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could be a result of the loss of integrin-mediated adhesion to the elastic fiber network and, therefore, a loss of cellular regulation.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by the Australian Research Council.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. A–D.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- EBP

- elastin-binding protein

- HDF

- human dermal fibroblasts

- BSA

- bovine serum albumin

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- MES

- 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Green L., Humphries M. (1999) Adv. Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 3–26 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newham P., Humphries M. J. (1996) Mol. Med. Today 2, 304–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aota S., Nomizu M., Yamada K. M. (1994) J Biol. Chem. 269, 24756–24761 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mithieux S. M., Weiss A. S. (2005) Adv. Protein Chem. 70, 437–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez F. (2000) Matrix Biol. 19, 455–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vrhovski B., Weiss A. S. (1998) Eur. J. Biochem. 258, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muiznieks L. D., Jensen S. A., Weiss A. S. (2003) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 410, 317–323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Antonicelli F., Bellon G., Debelle L., Hornebeck W. (2007) Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 79, 99–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duca L., Floquet N., Alix A. J., Haye B., Debelle L. (2004) Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 49, 235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kielty C. M. (2006) Expert Rev. Mol. Med. 8, 1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito S., Ishimaru S., Wilson S. E. (1998) Angiology 49, 289–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mecham R. P., Hinek A., Entwistle R., Wrenn D. S., Griffin G. L., Senior R. M. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 3716–3722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodgers U. R., Weiss A. S. (2004) Biochimie 86, 173–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broekelmann T. J., Kozel B. A., Ishibashi H., Werneck C. C., Keeley F. W., Zhang L., Mecham R. P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40939–40947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanagisawa H., Davis E. C., Starcher B. C., Ouchi T., Yanagisawa M., Richardson J. A., Olson E. N. (2002) Nature 415, 168–171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakamura T., Lozano P. R., Ikeda Y., Iwanaga Y., Hinek A., Minamisawa S., Cheng C. F., Kobuke K., Dalton N., Takada Y., Tashiro K., Ross J., Jr., Honjo T., Chien K. R. (2002) Nature 415, 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Senior R. M., Griffin G. L., Mecham R. P., Wrenn D. S., Prasad K. U., Urry D. W. (1984) J. Cell Biol. 99, 870–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karnik S. K., Wythe J. D., Sorensen L., Brooke B. S., Urness L. D., Li D. Y. (2003) Matrix Biol. 22, 409–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karnik S. K., Brooke B. S., Bayes-Genis A., Sorensen L., Wythe J. D., Schwartz R. S., Keating M. T., Li D. Y. (2003) Development 130, 411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senior R. M., Griffin G. L., Mecham R. P. (1982) J. Clin. Invest. 70, 614–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jung S., Rutka J. T., Hinek A. (1998) J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 57, 439–448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robinet A., Fahem A., Cauchard J. H., Huet E., Vincent L., Lorimier S., Antonicelli F., Soria C., Crepin M., Hornebeck W., Bellon G. (2005) J. Cell Sci. 118, 343–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greiling D., Clark R. A. (1997) J. Cell Sci. 110, 861–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang M. C., He L., Giro M., Yong S. L., Tiller G. E., Davidson J. M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 981–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tassabehji M., Metcalfe K., Hurst J., Ashcroft G. S., Kielty C., Wilmot C., Donnai D., Read A. P., Jones C. J. (1998) Hum. Mol. Genet. 7, 1021–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez-Revenga L., Iranzo P., Badenas C., Puig S., Carrió A., Milà M. (2004) Arch. Dermatol. 140, 1135–1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn C. N., del Pilar Martin M., Schröder M., Vanier M. T., Hara Y., Suzuki K., Suzuki K., d'Azzo A. (1997) Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 205–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelleher C. M., Silverman E. K., Broekelmann T., Litonjua A. A., Hernandez M., Sylvia J. S., Stoler J., Reilly J. J., Chapman H. A., Speizer F. E., Weiss S. T., Mecham R. P., Raby B. A. (2005) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 33, 355–362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodgers U. R., Weiss A. S. (2005) Pathol. Biol. 53, 390–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kielty C. M., Stephan S., Sherratt M. J., Williamson M., Shuttleworth C. A. (2007) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 362, 1293–1312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williamson M. R., Shuttleworth C. A., Canfield A. E, Black R. A., Kielty C. M. (2007) Biomaterials 28, 5307–5318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu W. J., Vrhovski B., Weiss A. S. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21719–21724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humphries M. J. (1998) Curr. Prot. Cell Biol. 9.1.1–9.1.11 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis E. C. (1993) Cell Tissue Res. 272, 211–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lomas A. C., Mellody K. T., Freeman L. J., Bax D. V., Shuttleworth C. A., Kielty C. M. (2007) Biochem. J. 405, 417–428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bax D. V., Bernard S. E., Lomas A., Morgan A., Humphries J., Shuttleworth C. A., Humphries M. J., Kielty C. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 34605–34616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broekelmann T. J., Ciliberto C. H., Shifren A., Mecham R. P. (2008) Matrix Biol. 27, 631–639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mould A. P. (1996) J. Cell Sci. 109, 2613–2618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morgan M. R., Humphries M. J., Bass M. D. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 957–969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wachi H., Nonaka R., Sato F., Shibata-Sato K., Ishida M., Iketani S., Maeda I., Okamoto K., Urban Z., Onoue S., Seyama Y. (2008) J. Biochem. 143, 633–639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rock M. J., Cain S. A., Freeman L. J., Morgan A., Mellody K., Marson A., Shuttleworth C. A., Weiss A. S., Kielty C. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23748–23758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemaire R., Bayle J., Mecham R. P., Lafyatis R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 800–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibson M. A., Leavesley D. I., Ashman L. K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 13060–13065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nymalm Y., Puranen J. S., Nyholm T. K., Käpylä J., Kidron H., Pentikäinen O. T., Airenne T. T., Heino J., Slotte J. P., Johnson M. S., Salminen T. A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7962–7970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leiss M., Beckmann K., Girós A., Costell M., Fässler R. (2008) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20, 502–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choi E. T., Khan M. F., Leidenfrost J. E., Collins E. T., Boc K. P., Villa B. R., Novack D. V., Parks W. C., Abendschein D. R. (2004) Circulation 109, 1564–1569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.