Abstract

Mgm1, the yeast ortholog of mammalian OPA1, is a key component in mitochondrial membrane fusion and is required for maintaining mitochondrial dynamics and morphology. We showed recently that the purified short isoform of Mgm1 (s-Mgm1) possesses GTPase activity, self-assembles into low order oligomers, and interacts specifically with negatively charged phospholipids (Meglei, G., and McQuibban, G. A. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 1774–1784). Here, we demonstrate that s-Mgm1 binds to a mixture of phospholipids characteristic of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Binding to physiologically representative lipids results in ∼50-fold stimulation of s-Mgm1 GTPase activity. s-Mgm1 point mutants that are defective in oligomerization and lipid binding do not exhibit such stimulation and do not function in vivo. Electron microscopy and lipid turbidity assays demonstrate that s-Mgm1 promotes liposome interaction. Furthermore, s-Mgm1 assembles onto liposomes as oligomeric rings with 3-fold symmetry. The projection map of negatively stained s-Mgm1 shows six monomers, consistent with two stacked trimers. Taken together, our data identify a lipid-binding domain in Mgm1, and the structural analysis suggests a model of how Mgm1 promotes the fusion of opposing mitochondrial inner membranes.

Mitochondrial dynamics have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases such as dominant optic atrophy and Parkinson disease (1, 2). Mitochondrial morphology is regulated by balanced membrane fusion and fission reactions that are orchestrated by members of the highly conserved dynamin-related protein family (3). Dynamin-related proteins are large GTPases that can self-assemble and promote membrane remodeling (4, 5). We have shown previously that the dynamin-related protein Mgm1 has GTPase activity, self-assembles into low order oligomers, and binds to negatively charged phospholipids (6). Mgm1 exists as two isoforms in the mitochondria; l-Mgm12 is anchored to the IM via a transmembrane domain, and s-Mgm1 is peripherally associated with the IM and also found in the intermembrane space. s-Mgm1 results from the regulated cleavage by the mitochondrial rhomboid protease (7, 8). It was shown recently that both isoforms are essential but have distinct roles in mitochondrial membrane fusion whereby only s-Mgm1 requires its GTPase activity (9). It is proposed that l-Mgm1 serves as a receptor for s-Mgm1 to mediate fusion of opposing membranes upon GTP hydrolysis. Here, we provide molecular data indicating that lipid binding of s-Mgm1 is required for proper membrane fusion. Furthermore, structural analysis of s-Mgm1 assembled onto liposomes suggests a model whereby stacked trimers of s-Mgm1 on opposing membranes would facilitate fusion.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Expression and Purification of s-Mgm1

WT s-Mgm1 and point mutants were purified in buffer containing 500 mm NaCl and 1 mm dithiothreitol as described previously (6). For all subsequent in vitro assays presented here, purified WT s-Mgm1 and point mutants were diluted into buffers containing 170 mm NaCl and 1 mm dithiothreitol immediately prior to the assay.

Liposome Preparation

A 10 mg/ml chloroform solution of lipid (Avanti Polar Lipids) was dried by rotary evaporation and vacuum pump, yielding a thin lipid film. The lipid suspension in physiological salt buffer was extruded 15 times through a 1-μm polycarbonate NucleoporeTM track-etched membrane (Whatman) to generate unilamellar vesicles.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay

IM liposomes were prepared with the corresponding physiological concentrations: cardiolipin, 16%; phosphatidylethanolamine, 24%; phosphatidic acid, 2%; phosphatidylserine, 4%; phosphatidylcholine, 38%; and phosphatidylinositol, 16%. 2 μg of total lipid was added to each well of a 96-well plate and allowed to coat overnight. Following 5% bovine serum albumin block, Mgm1 proteins were added at the concentrations indicated. Binding was detected using primary antibody directed against His6-tagged Mgm1, followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Color development was monitored at 655 nm using tetramethylbenzidine as a horseradish peroxidase substrate.

Gel Filtration and CD

Gel filtration and CD analysis were done as described previously (6).

GTPase Activity Assay

The malachite green colorimetric phosphate assay was performed as described previously (6).

Lipid Turbidity Assay

The kinetic mode of a Thermo Scientific BioMateTM 3 UV-visible spectrophotometer was used to measure the change in A350 to monitor change in particle size in real time.

Electron Microscopy

s-Mgm1 was diluted into low salt buffer and incubated with liposome solution at room temperature for 15 min. The sample was blotted onto an EM grid and stained with 2% uranyl acetate. The samples were visualized using a Tecnai F20 electron microscope (FEI Co., Eindhoven, The Netherlands) equipped with a field emission gun and operating at 200 kV. Images were recorded at a magnification of ×50,000. Two-dimensional crystal analysis was performed as described previously (10, 11).

In Vivo Complementation Assay and Fluorescence Microscopy

Plasmid shuffle complementation and imaging of mitochondrial morphology were performed as described previously (8).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Conserved Lysines Constitute a Lipid-binding Domain within s-Mgm1

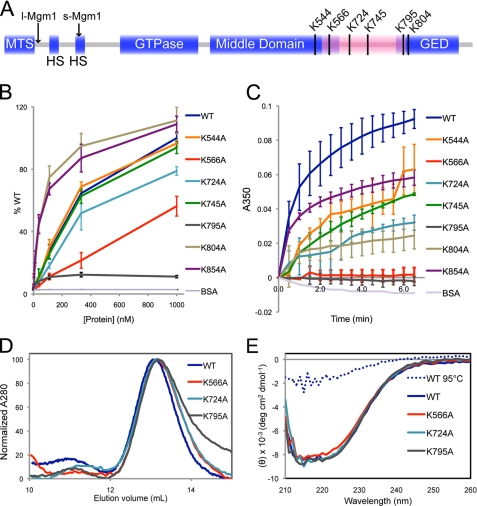

In our previous study (6), s-Mgm1 interactions with single phospholipids were assayed by lipid overlay Western blotting. Here, we conducted an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to quantitatively monitor the association of s-Mgm1 and several potential lipid-binding point mutants within the putative lipid-binding domain with liposomes with a composition characteristic of the mitochondrial IM. Sequence alignment of 22 fungal sequences homologous to Mgm1 identified several conserved lysines (Lys544, Lys566, Lys724, Lys745, Lys795, and Lys804) that could serve as interaction motifs for the negatively charged phospholipids (Fig. 1A). In addition, we included Lys854 in our analyses, as this residue is known to be required for s-Mgm1 protein oligomerization (6). Consistent with our previous report, K795A was severely compromised in lipid binding (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, K566A and K724A displayed a significant reduction in lipid binding compared with WT s-Mgm1 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, K544A, K745A, K804A, and K854A showed little difference in lipid binding compared with WT s-Mgm1 (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

s-Mgm1 contains a lipid-binding domain that directs binding to lipids of the mitochondrial IM. A, an Mgm1 schematic illustrates the mitochondrial targeting sequence (MTS), hydrophobic segments (HS), GTPase domain, middle domain, and GTPase effector domain (GED). Arrows indicate the cleavage sites for processing into l-Mgm1 and s-Mgm1. The predicted lipid-binding domain is highlighted in pink, and the conserved lysines in this region are indicated. B, the binding of s-Mgm1 and several lysine mutants to IM liposomes was assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The amount of s-Mgm1 lysine mutants bound to the IM-coated wells was normalized to WT s-Mgm1 (% WT). BSA, bovine serum albumin. C, lipid aggregation induced by s-Mgm1 and lysine mutants was assayed by monitoring lipid turbidity at 350 nm. D, WT s-Mgm1 and three representative lysine point mutants were subjected to gel filtration chromatography. E, shown are the results from CD spectroscopy of WT s-Mgm1 and three representative lysine mutants. WT s-Mgm1 after heat denaturation was included as a control for the unfolded state. IM liposomes were made from a mixture of phospholipids with the corresponding physiological concentrations: cardiolipin, 16%; phosphatidylethanolamine, 24%; phosphatidic acid, 2%; phosphatidylserine, 4%; phosphatidylcholine, 38%; and phosphatidylinositol, 16%. deg, degrees.

In addition to the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay approach, we also conducted a spectroscopic turbidity assay (12). This assay measures the ability of Mgm1 not only to interact with liposomes but also to induce aggregation presumably based on trans-interactions of Mgm1 on opposing liposomes. WT s-Mgm1, K544A, K745A, and K854A were able to induce significant liposome aggregation, whereas K724A and K804A induced moderate liposome aggregation (Fig. 1C). K566A and K795A were completely devoid of this activity (Fig. 1C). To demonstrate that the mutant Mgm1 proteins did not undergo significant protein misfolding, we conducted gel filtration and CD analysis (Fig. 1, D and E). The traces of K566A, K724A, and K795A overlapped that of WT Mgm1 in both assays, indicating that these point mutants maintain proper folding and oligomerization properties.

These results demonstrate that several conserved lysines in this region of s-Mgm1 are required to maintain proper lipid interaction. Given the position of this domain between the middle and GTPase effector domains of Mgm1, we propose that this region provides a lipid interaction interface similar to the PH domain in other dynamins (13).

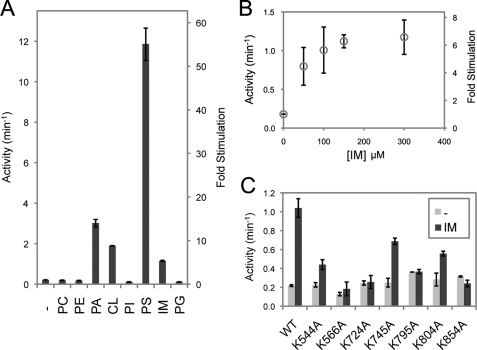

s-Mgm1 GTPase Activity Is Stimulated by Phospholipids

Previously, we characterized the GTPase activity of purified Mgm1, which was consistent with a basal level of hydrolysis found in other dynamins (6). Classical dynamins are known to undergo stimulated GTPase activity upon lipid-induced oligomerization (14). We therefore tested for the ability of a variety of phospholipids to stimulate the activity of s-Mgm1. Of the lipids tested, we found that phosphatidylserine stimulated the GTPase activity of s-Mgm1 by 55-fold, whereas phosphatidic acid- and cardiolipin-containing liposomes resulted in GTPase stimulation of 14- and 9-fold, respectively (Fig. 2A). Importantly, these are the lipids we reported previously that s-Mgm1 binds, and cardiolipin is physiologically relevant to the mitochondrial IM (15). Furthermore, we tested whether a mixture of lipids representing the content of the mitochondrial IM could stimulate s-Mgm1 GTPase activity. Our IM liposomes had the following content: 16% cardiolipin, 24% phosphatidylethanolamine, 2% phosphatidic acid, 4% phosphatidylserine, 38% phosphatidylcholine, and 16% phosphatidylinositol. IM liposomes were able to stimulate the GTPase activity by 6-fold in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2, A and B). These results demonstrate that Mgm1 behaves similarly to other dynamin proteins and suggest that lipid interaction is mechanistically important for Mgm1 to function at the mitochondrial IM.

FIGURE 2.

s-Mgm1 binding to lipids results in stimulated GTPase activity. A, the GTPase activity of s-Mgm1 was assayed in the presence or absence of various phospholipid-containing liposomes. The -fold stimulation was calculated in relation to the basal activity of s-Mgm1 in the absence of liposome. Phosphatidylglycerol (PG) is a negatively charged phospholipid but is not present in the mitochondrial IM and served as a control. PC, phosphatidylcholine; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine; PA, phosphatidic acid; CL, cardiolipin; PI, phosphatidylinositol; PS, phosphatidylserine. B, GTP activity of s-Mgm1 was determined with increasing amounts of IM liposomes present. C, several lysine point mutants in the putative lipid-binding domain of s-Mgm1 were tested for GTPase stimulation by IM liposomes. All of the experiments were done in triplicate.

s-Mgm1 Lipid Binding Is Required for Stimulated GTPase Activity

Classical dynamins have a PH domain between the middle and GTPase effector domains that mediates lipid association (13). We have now identified several conserved lysines that contribute to lipid binding (Fig. 1, A–C) and suggest that they form a lipid-binding module in Mgm1. We therefore determined whether these mutants are impaired in IM liposome-stimulated GTP hydrolysis. K566A, K724A, K795A, and K854A have lost the ability to undergo significant lipid-dependent stimulation, whereas K544A, K745A, and K804A maintain IM-mediated stimulated GTP hydrolysis (Fig. 2C). K854A does not undergo oligomerization (6) but maintains lipid interaction (Fig. 1B) and serves as a control for oligomerization-dependent stimulation (Fig. 2C). These data suggest that both phospholipid interaction and oligomerization are necessary for stimulated GTPase activity and that Mgm1 contains a lipid interaction domain similar to the PH domain in other dynamins.

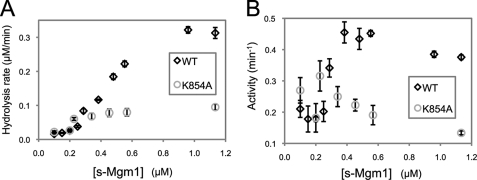

s-Mgm1 Displays Positive Cooperativity in GTPase Activity

Lipid-stimulated GTPase activities of other dynamins have been well studied and are due to self-assembly of the dynamin onto liposomes. We have investigated the effect of s-Mgm1 self-assembly on GTPase activity. We have shown previously that s-Mgm1 can self-assemble into low order oligomers under high salt conditions. Here, we determined the GTPase activity of WT s-Mgm1 and the oligomerization-defective mutant K854A at various protein concentrations under low salt (170 mm NaCl) conditions. We found that GTP hydrolysis of WT s-Mgm1 increased in a nonlinear fashion compared with the oligomerization-defective mutant K854A (Fig. 3, A and B). The sigmoidal curve in the activity plot indicates positive cooperativity at low concentrations of the WT. A sharp increase in WT GTPase activity was observed at protein concentrations of 0.2–0.4 μm. In contrast, we observed a slow increase in GTP hydrolysis for the K854A mutant. These data further support the idea that oligomerization of s-Mgm1 is essential for its GTPase activity and function.

FIGURE 3.

Oligomerization induces stimulated GTPase activity. The GTP hydrolysis of s-Mgm1 was determined as the concentration of WT s-Mgm1 or mutant K854A was increased. The same set of data was plotted as GTP hydrolysis rate (A) and specific activity (B). All of the experiments were done in triplicate.

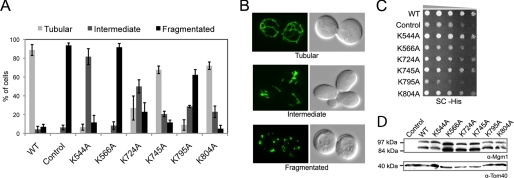

In Vivo Complementation of s-Mgm1 Requires Lipid Association

To further understand the biological role of Mgm1 lipid binding, we conducted complementation studies in yeast using a plasmid shuffle approach. We tested the ability of K544A, K566A, K724A, K745A, K795A, and K804A to restore normal growth and normal mitochondrial morphology to cells lacking WT Mgm1. K566A and K795A could not complement mitochondrial morphology or growth (Fig. 4, A and C). K544A and K724A displayed some rescue of mitochondrial morphology. K745A and K804A retained almost WT levels of mitochondrial morphology and growth (Fig. 4, A and C). Importantly, all mutants were expressed at similar levels and produced equivalent amounts of both l-Mgm1 and s-Mgm1 (Fig. 4D). Consistently, the in vivo complementation ability of these point mutants correlates well with the in vitro ability of these mutants to interact with and be stimulated by IM lipids. Taken together, these data demonstrate that the lipid-binding activity of Mgm1 is required for this protein to function properly in vivo and provide compelling evidence that Mgm1 contains a lipid-binding domain.

FIGURE 4.

s-Mgm1 mutants defective in IM binding and stimulated GTPase activity have impaired function in vivo. A, the mitochondrial morphology of complementation strains (Control represents no Mgm1 expressed) was scored by fluorescence microscopy of a mitochondrially targeted green fluorescent protein. 300 cells were counted for each mutant complementation experiment. B, shown are representative micrographs of mitochondrial green fluorescent protein morphology that categorizes tubular (upper panel), intermediate (middle panel), and fragmented (lower panel) morphology. C, serial dilution onto synthetic complete medium (SC) demonstrated growth rates of lipid-binding mutants (Control represents no Mgm1 expressed). D, Western blot analysis of mutant strains (Control represents no Mgm1 expressed) demonstrated that Mgm1 was processed in all mutants tested (upper panel) and expressed to similar levels normalized to Tom40 levels (lower panel).

s-Mgm1 Causes Aggregation of IM Liposomes

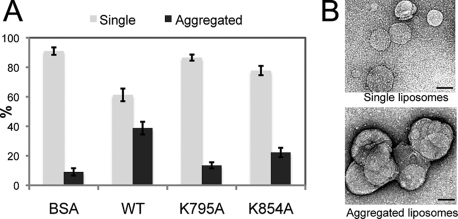

The self-assembly of dynamins onto lipids and their ability to promote tubulation of liposomes have been thoroughly studied and visualized by EM (14). Therefore, we tested whether s-Mgm1 can induce tubulation of IM liposomes. Instead of tubulation, we observed that s-Mgm1 induced the assembly of liposomes into aggregates compared with a bovine serum albumin control (Fig. 5, A and B). In agreement with the lipid binding studies above, we found that the lipid-binding mutant K795A could not induce liposome aggregation (Fig. 5A). In addition, we found that the oligomerization-defective mutant K854A was also impaired in lipid aggregation. These results indicate that both lipid binding and Mgm1 assembly into oligomers are required to induce liposome assembly.

FIGURE 5.

s-Mgm1 promotes liposome aggregation. A, EM analysis was performed to visualize and quantify the extent of lipid aggregation induced by s-Mgm1. BSA, bovine serum albumin. B, the liposomes were categorized into either single liposomes (gray bars) or large liposome aggregates (black bars). Scale bars = 0.1 μm.

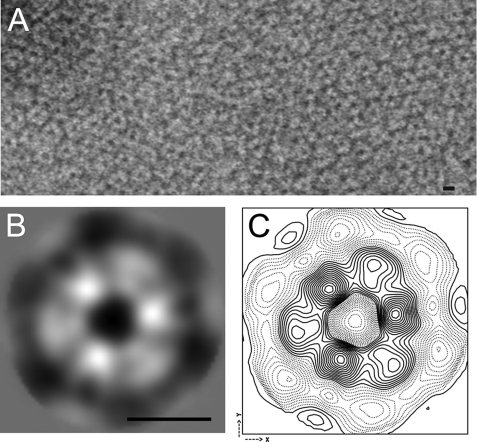

s-Mgm1 Assembles onto IM Liposomes and Forms a Two-dimensional Crystalline Array

Although s-Mgm1 on its own did not induce liposome tubulation, EM analysis revealed arrays of s-Mgm1 rings on IM liposomes (Fig. 6A). The arrays were composed of regions of ordered lattice. Processing of images with two-dimensional crystal analysis software (11) showed that well ordered regions contain a single lattice with p3 symmetry. To calculate an average projection of the stained s-Mgm1 oligomer, ∼1000 images of oligomers were interactively selected from images of crystals and treated as unordered single particles. Oligomer images were rotationally and translationally aligned and averaged without assuming any symmetry. The resulting average revealed six densities arranged with clear 3-fold symmetry. The diameter of each unit density is ∼50 Å, which is consistent with an 86-kDa s-Mgm1 monomer. A high signal-to-noise symmetrized average and contour map are shown in Fig. 6 (B and C). Given the clear difference in staining of the two different types of monomer in the hexamer, we propose that this reflects two s-Mgm1 trimers that have stacked on top of each other with a 60° rotational offset. This orientation of s-Mgm1 trimers assembled onto liposomes suggests a mechanism of membrane fusion: trimers of s-Mgm1 on opposing membranes could stack on each other, and GTP hydrolysis might induce a conformational change to induce fusion of the lipids and subsequent release of the stacked trimer. Further studies will be required to understand the exact mechanism of Mgm1-mediated membrane fusion, but our data pinpoint the critical requirement for lipid association of Mgm1 to function in mitochondrial dynamics.

FIGURE 6.

s-Mgm1 assembles onto IM liposomes as oligomeric rings. A, oligomeric rings of s-Mgm1 assembled onto IM liposomes. A small patch of an ordered array formed by s-Mgm1 is shown. B, averaged image of the s-Mgm1 particle that consists of six monomer densities. C, contour map of the s-Mgm1 hexamer. Scale bars = 10 nm.

Acknowledgment

We thank Stephanie Bueler for assistance with EM analysis.

This work was supported by an operating grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (to G. A. M.).

- l-Mgm1

- long Mgm1

- s-Mgm1

- short Mgm1

- IM

- inner membrane

- WT

- wild-type

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- EM

- electron microscopy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whitworth A. J., Lee J. R., Ho V. M., Flick R., Chowdhury R., McQuibban G. A. (2008) Dis. Model. Mech. 1, 168–174; Discussion 173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park J., Kim Y., Chung J. (2009) Dis. Model. Mech. 2, 336–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto K., Shaw J. M. (2005) Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 503–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoppins S., Lackner L., Nunnari J. (2007) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 751–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw J. M., Nunnari J. (2002) Trends Cell Biol. 12, 178–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meglei G., McQuibban G. A. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 1774–1784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herlan M., Vogel F., Bornhovd C., Neupert W., Reichert A. S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 27781–27788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McQuibban G. A., Saurya S., Freeman M. (2003) Nature 423, 537–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zick M., Duvezin-Caubet S., Schäfer A., Vogel F., Neupert W., Reichert A. S. (2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 2237–2243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowther R. A., Henderson R., Smith J. M. (1996) J. Struct. Biol. 116, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gipson B., Zeng X., Zhang Z. Y., Stahlberg H. (2007) J. Struct. Biol. 157, 64–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connell E., Scott P., Davletov B. (2008) Anal. Biochem. 377, 83–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Praefcke G. J., McMahon H. T. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 133–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mears J. A., Hinshaw J. E. (2008) Methods Cell Biol. 88, 237–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schlame M., Hostetler K. Y. (1997) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1348, 207–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]