Abstract

The multicellular behavior of the myxobacterium Myxococcus xanthus requires the participation of an elevated number of signal-transduction mechanisms to coordinate the cell movements and the sequential changes in gene expression patterns that lead to the morphogenetic and differentiation events. These signal-transduction mechanisms are mainly based on two-component systems and on the reversible phosphorylation of protein targets mediated by eukaryotic-like protein kinases and phosphatases. Among all these factors, protein phosphatases are the elements that remain less characterized. Hence, we have studied in this work the physiological role and biochemical activity of the protein phosphatase of the family PPP (phosphoprotein phosphatases) designated as Pph2, which is forming part of the same operon as the two-component system phoPR1. We have demonstrated that this operon is induced upon starvation in response to the depletion of the cell energy levels. The increase in the expression of the operon contributes to an efficient use of the scarce energy resources available for developing cells to ensure the completion of the life cycle. In fact, a Δpph2 mutant is defective in aggregation, sporulation yield, morphology of the myxospores, and germination efficiency. The yeast two-hybrid technology has shown that Pph2 interacts with the gene products of MXAN_1875 and 5630, which encode a hypothetical protein and a glutamine synthetase, respectively. Because Pph2 exhibits Ser/Thr, and to some extent Tyr, Mn2+-dependent protein phosphatase activity, it is expected that this function is accomplished by dephosphorylation of the specific protein substrates.

Myxococcus xanthus is a soil-dwelling δ-Proteobacterium that undergoes a life cycle unique among the prokaryotes. During growth, cells form predatory communities known as swarms, which feed cooperatively. Upon starvation, cells initiate a multicellular developmental program that culminates with the formation of macroscopic fruiting bodies filled with resistant myxospores. The spores remain dormant until nutrients are available again, when they germinate and initiate a new vegetative cycle (1). This complex lifestyle forces the cells not only to scrutinize all the changes in their environment, but also to maintain a precise communication with each other to coordinate their movement and behavior. In fact, signal-transduction mechanisms of diverse nature have been reported to function in the cell synchronization required during development (2, 3). One of these mechanisms is based on eukaryotic-like protein kinases (ELKs),3 which originate phosphoesters on Ser/Thr/Tyr residues. Thus, the myxobacterial kinome is the largest one among the prokaryotes, which seems to correlate with their multicellular behavior (4). The presence of ELKs implies the need of protein phosphatases (PPs) to revert the action of the kinases. These two types of proteins will function together to switch on and off the signal-transduction pathways where they participate by their opposite action on specific protein substrates. Actually, the phosphorylation levels of the substrates will depend on the balance between the activities of ELKs and PPs (5, 6).

PPs are grouped into three families designated as phosphoprotein phosphatases (PPPs), Mn2+- or Mg2+-dependent phosphatases (PPMs), and phosphotyrosine phosphatases. These families differ in their catalytic mechanisms, phosphoamino acids on which they preferentially act, and sequence and structural features (7). The PPP family represents the largest source of Ser/Thr PPs in eukaryotes (8). Although PPP phosphatases are also encoded by prokaryotes, only a small number of these proteins have been characterized, which have been involved in several unrelated functions (9–13).

The in silico analysis of the M. xanthus genome has revealed the presence of 34 genes whose predicted protein products exhibit similarities with the conserved sequence features associated to PPs (3). This number is very large compared with most of the prokaryotes, with the exception of those bacteria with a developmental cycle (14). The 34 M. xanthus PPs are distributed in the three families, being the PPP phosphatases that are the most abundant. Despite the importance that the team ELKs/PPs seems to play in M. xanthus signal-transduction systems, most of the research has been carried out with ELKs (3), whereas the work on PPs has not been carried out in depth. In 1990, five different phosphatase activities were detected in M. xanthus (15), which have not been associated to any specific protein, so far. Hence, Whitworth et al. (16) suggested that those phosphatase activities could be originated by specific PPs. Until now, only Pph1 has been characterized (17). Pph1, which belongs to the PPM family, interacts with FrzZ, a protein involved in the regulation of the movement of M. xanthus cells during growth and development. As a consequence, a pph1 mutant exhibits defects in cell motility. In our laboratory, in an attempt to clone genes coding for phosphatases, we identified three two-component systems (TCSs) involved in the regulation of the expression of Mg2+-independent acid and neutral phosphatases (18, 19). Deletion of one of these systems, PhoPR1, caused defects in development. Here we show that the gene MXAN_4779, localized in the vicinity of phoPR1, encodes a phosphatase of the family PPP with the ability to act on phosphorylated Ser, Thr, and Tyr residues; this phosphatase has been named Pph2. Studies on expression profiles and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR analyses have revealed that pph2 is coexpressed with phoPR1. Furthermore, the phenotypic analysis of a pph2 deletion mutant has shown defects in aggregation, sporulation, and germination, which seem to be originated by a lack of sufficient energy in the cells to complete the life cycle.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, Growth Conditions, and Nucleic Acids Manipulations

M. xanthus and Escherichia coli strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. M. xanthus strains were grown at 30 °C in liquid CTT (1% Bacto-Casitone, 2% MgSO4·7H2O, 1 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.6, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) with vigorous shaking as previously described (19). When necessary, kanamycin (80 μg/ml), 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal, 100 μg/ml), or galactose (10 mg/ml) were added. E. coli strains were grown at 37 °C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (20), which was supplemented with kanamycin (25 μg/ml) or X-Gal (100 μg/ml) when needed. For solid media, Bacto-Agar (Difco) was added to a concentration of 1.5%. When required, the protonophore carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) was included in the media at the concentrations indicated in the corresponding figures. Routine molecular biology techniques were used for nucleic acid manipulations (20). Plasmids were introduced into E. coli by transformation and into M. xanthus by electroporation (21). For the RT-PCR experiment, total RNA was prepared by using the High Pure RNA Isolation kit provided by Roche Applied Science. Samples were treated with the kit DNA-free (Ambion) to completely remove chromosomal DNA. The RNA was then subjected to RT using the primer RTSC, which anneals 326 bp downstream of the pph2 gene (Fig. 2 and Table 2), according to the instructions of the kit SuperScriptTM II reverse transcriptase from Invitrogen. The cDNA thus obtained was amplified by 30 cycles of PCR with the primer pairs RTF2-RTF2C, RTR1A-RTR1B, and RTP1F-RTP1R, which anneal inside pph2, phoR1, and phoP1, respectively. PCR products were analyzed by using 5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial and yeast strains and plasmids used in this study

| Bacterial and yeast strains | Genotype/phenotypea | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | F′[traD36 proAB+ lacIq lacZ ΔM15] recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ(lac-proAB) | Yanisch-Perron et al. (45) |

| TOP10 | F−mcrA Δ(mrr-hsdRMS-mcrBC) Φ80lacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 recA1 araD139 Δ(ara-leu)7697 galU galK rpsL (StrR) endA1 nupG | Invitrogen |

| BL21(DE3)Star | F−ompT hsdSB (rB−mB−) gal dcm rne131 (DE3) | Invitrogen |

| DH10B | FP−PmcrA Δ(mrr hsdRMS mcrBC) Φ80dlacZΔM15 ΔlacX74 endA1 recA1 deoR Δ(ara, leu)7697 araD139 galU galK nupG rpsL | Gibco BRL |

| M. xanthus | ||

| DZF1 | Wild type | Morrison and Zusman (46) |

| JM12IF | ΔMXAN4777–4778, GalR, KmS | This study |

| Δpph2 | ΔMXAN4779, GalR, KmS | This study |

| Pph2LZ | ΔMXAN4779-lacZ, KmR | This study |

| S. cerevisiae | ||

| AH109 | MATa, trp1–901, leu2–3, 112, ura3–52, his3–200, gal4Δ, gal80Δ, LYS2 ::GAL1BUASB-GAL1BTATAB-HIS3, GAL2BUASB-GAL2BTATAB-ADE2, URA3 ::MEL1BUASB-MEL1BTATAB-lacZ, MEL1 | James et al. (26) |

| Control + | AH109 harboring plasmid pGBKT7–53 and pGADT7-T | Clontech |

| Control − | AH109 harboring plasmid pGBKT7-Lam and pGADT7-T | Clontech |

| Pph2-MXAN1875 | AH109 harboring plasmid pGBKT7-Pph2 and pGADC3-internal fragment of MXAN1875 | This study |

| Pph2-MXAN5630 | AH109 harboring plasmid pGBKT7-Pph2 and pGADC3-internal fragment of MXAN5630 | This study |

| Plasmids | Relevant features and/or genesa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pBJ113 | galK, KmR | Julien et al. (23) |

| pKY481 | lacZY, KmR | Cho and Zusman (22) |

| P1 | AmpR | Martínez-Cañamero et al. (24) |

| pET200/D-TOPO | Expression vector, KmR | Invitrogen |

| pΔpph2 | ΔMXAN4779, KmR | This study |

| pΔphoPR1IF | ΔMXAN4777–4778, KmR | This study |

| pKY-Pph2 | MXAN4779-lacZ, KmR | This study |

| pETTopo200-Pph2N | pET with MXAN4779, KmR | This study |

| pETTopo200-GS | pET with MXAN5630, KmR | This study |

| pGBKT7 | GAL4 DNA-binding domain fusion expression vector for Y2H, KmR, TRP1 | Clontech |

| pGBKT7-Pph2 | Pph2-GAL4 DNA-binding domain fusion, KmR, TRP1 | This study |

| pGAD-C1∼C3 | Library of random fragments from M. xanthus DZF1-GAL4 activation domain fusions, AmpR, LEU2 | James et al. (26) |

a KmR, KmS, AmpR, and GalR indicate kanamycin resistance, kanamycin sensitivity, ampicillin resistance, and galactose resistance, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotides used in this study

| Oligonucleotide | Purpose | Sequence (5′→3′)a |

|---|---|---|

| RTSC | Synthesis of cDNA from MXAN4780 | AGGTCGACGATGCGCTTGTG |

| RTF2 | Amplification inside pph2 (PCR3) | TACCGGGAGAAGGACCACTG |

| RTF2C | Amplification inside pph2 (PCR3) | TCCATCAGCGCGTTGTGGTG |

| RTR1A | Amplification inside phoR1 (PCR2) | TCTTCCACGACGTCACCGAG |

| RTR1B | Amplification inside phoR1 (PCR2) | TGCTCGTACTCACCGTAAAC |

| RTP1F | Amplification inside phoP1 (PCR1) | CATCCTGATTATCGAGGACG |

| RTP1R | Amplification inside phoP1 (PCR1) | ACTTCCTCGCCCTTCACACG |

| Pph2LZXhoF | Amplification of upstream of MXAN4779 (pKY-Pph2) | TCCTCGAGACGCCGCTGGCCAAGGATTT |

| Pph2LZBamR | Amplification of upstream of MXAN4779 (pKY-Pph2) | CGGGATCCATGGTCACTCCATCCTACCC |

| Pph2ER | Amplification of downstream of MXAN4779 (pΔpph2) | GGAGAATTCGCTGCTCCATCCGGAGC |

| Pph2XF | Amplification of downstream of MXAN4779 (pΔpph2) | GCGCAACCTCGAGGAGTCGC |

| PhoP1HindIII | Amplification of upstream of MXAN4777 (pΔphoPR1) | GGAAGCTTAGATGGAGTACTACTTCGAG |

| PhoP1BamHI | Amplification of upstream of MXAN4777 (pΔphoPR1) | TCGGATCCAATCAGGATGCGCGACATGA |

| PhoR1BamHI | Amplification of downstream of MXAN4778 (pΔphoPR1) | CGGGATCCTCGAGCGCGGCGACAGGGTA |

| PhoR1EcoRI | Amplification of downstream of MXAN4778 (pΔphoPR1) | GTGAATTCAGCGCGCCTCCACCAGCTTG |

| pTOP-Pph2F | Amplification of MXAN4779 (pTTopo200-Pph2N) | CACCATGCGGGTCGCCATCCT |

| pTop2-Pph2R | Amplification of MXAN4779 (pTTopo200-Pph2N) | CTACCCTTCGAAATCGTTGAG |

| Pph2Eco2HF | Amplification of MXAN4779 (pGBKT7-Pph2) | GAGAATTCATGCGGGTCGCCATCCTCGC |

| pETTopo2-GlnF | Amplification of MXAN5630 (pTTopo200-GS) | CACCGTGGACACGCTGCGCCGCTG |

| pETTopo2-GlnR | Amplification of MXAN5630 (pTTopo200-GS) | TCAGATGAGCTCCAGGTAAC |

| Pph2Pst2HR | Amplification of MXAN4779 (pGBKT7-Pph2) | GACTGCAGCTACCCTTCGAAATCGTTGA |

| pGADSecF | Sequencing of fragments identified during M. xanthus genomic library yeast-two hybrid screening | TAACTATCTATTCGATGATGA |

a Underlined are the restriction sites used in cloning and the sequence CACC for cloning into pET200/D-TOPO vector.

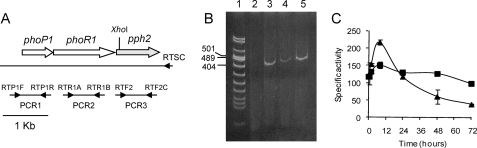

FIGURE 2.

The genes pph2 and phoPR1 form an operon. A, genetic organization of phoP1, phoR1, and pph2 on the chromosome of M. xanthus, and strategy used to study the coexpression of the three genes. The names of the oligonucleotides used as primers in each reaction (Table 2) are indicated on top of each small arrowhead used to represent them. The internal XhoI site in pph2 used in the construction of a Δpph2 mutant is indicated. B, RT-PCR experiment. Lane 1, DNA molecular weight standards; sizes in bp of only three of the fragments are indicated; lane 2, negative control using as template total RNA not subjected to RT and as primers RTP1F and RTP1R; lanes 3–5, PCR products obtained using as template the cDNA synthesized with the oligonucleotide RTSC, and as primers the oligonucleotides indicated in panel A to amplify PCR1, PCR2, and PCR3, respectively. C, expression time of pph2. β-Galactosidase-specific activity exhibited by the strain pph2-lacZ during growth on CTT (squares) and development on TPM (triangles) media is represented. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Developmental Conditions

The starvation media CF (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8, 8 mm MgSO4, 0.02% (NH4)2SO4, 0.015% Bacto-Casitone, 0.2% sodium citrate, 0.1% sodium pyruvate, 1.5% Bacto-Agar) and TPM (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 1 mm potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgSO4, 1.5% Bacto-Agar) were used to induce development (18). In some experiments, the media were supplemented with CCCP at the concentrations indicated in the figures. M. xanthus exponentially growing cells were concentrated after centrifugation to an optical density at 600 nm (A600) of 15 or 60 in TM buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 1 mm MgSO4), and 10-μl drops were spotted onto the starvation media. The progression of development was monitored with a Wild Heerbrugg dissecting microscope. For quantification of spores, 200 μl of concentrated cultures was spotted onto the media. At different times, the fruiting bodies of one plate were harvested and resuspended in 200 μl of TM buffer. Fruiting bodies were dispersed, and rod-shaped cells were disrupted by sonication. Myxospores were counted in a Petroff-Hausser chamber. For germination analyses, sonicated samples obtained at 72-h starvation were heated at 50 °C for 2 h, diluted, and plated onto CTT agar plates to obtain colonies. All the experiments were performed in triplicate.

Construction and Assay of a Strain Harboring a pph2-lacZ Fusion

The lacZ fusion was constructed using the plasmid pKY481 (22). By the use of the oligonucleotide pair Pph2LZXhoF-Pph2LZBamR (Table 2), a fragment encompassing the upstream pph2 region was amplified using the wild-type (WT) M. xanthus chromosomal DNA as template. The BamHI site in the primer was introduced at the start codon of the gene and in-frame with the BamHI site existing in the lacZ gene of plasmid pKY481. The PCR product was digested with XhoI and BamHI, and ligated to plasmid pKY481 digested with the same enzymes. The resulting plasmid, pKY-Pph2, was introduced into M. xanthus WT cells, and the kanamycin-resistant colonies obtained were analyzed by Southern blot to confirm the proper recombination event. The strain containing the fusion was incubated on CTT and TPM media, and cell extracts were obtained at various times by sonication and analyzed for β-galactosidase activity as previously reported (19). The protein content was determined by using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad), with bovine serum albumin as a standard. Specific activity is expressed as nanomoles of o-nitrophenol produced per minute and mg of protein.

Construction of the Deletion Strains JM12IF and Δpph2

The in-frame deletion strains were generated by using the plasmid pBJ113 (23). To obtain a phoPR1 deletion mutant an 800-bp fragment upstream of phoP1 and an 800-bp fragment downstream of phoR1 were amplified by PCR using the pairs of oligonucleotides PhoP1HindIII-PhoP1BamHI and PhoR1BamHI-PhoR1EcoRI, respectively (Table 2). The amplified products were then digested and cloned into pBJ113 to obtain plasmid pΔphoPR1.

For deletion of pph2, plasmid P1 (24) was digested with XhoI (a natural site inside the gene, which is shown in Fig. 2A) and EcoRI, and the 4200-bp fragment obtained, containing the upstream region of pph2, was ligated to the XhoI-EcoRI-digested PCR product amplified by using the primers Pph2ER-Pph2XF (Table 2). This PCR product contains the downstream region of pph2, and the XhoI site was designed in the same frame with the one upstream inside the gene. The plasmid was named pP1Pph2 and harbors a deletion of 330 bp of pph2, containing domains II and III of the protein phosphatase. Next, the 3000-bp HindIII-EcoRI fragment from pP1Pph2 was cloned into pBJ113 digested with the same enzymes. The final plasmid was designated as pΔpph2. The plasmids pΔphoPR1 and pΔpph2, which harbor the corresponding gene deletion in phoPR1 and pph2, respectively, were introduced into WT M. xanthus. Chromosomal integration of the plasmids was selected by plating cells onto CTT agar plates containing 80 μg/ml kanamycin. Several randomly chosen kanamycin-resistant merodiploids were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization to confirm the proper recombination event. One positive strain for each plasmid was then grown in the absence of kanamycin and plated onto CTT agar plates containing galactose. Southern blot analysis was used again to screen several kanamycin-sensitive and galactose-resistant colonies obtained to verify the loss of the WT alleles. The strains thus obtained were designated as JM12IF (ΔphoPR1) and Δpph2.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

For transmission electron microscopy (TEM), myxospores were harvested from 72-h fruiting bodies on CF medium and treated as previously described (19). Photographs were taken in a Zeiss TEM902 transmission electron microscope at 80 kV.

Expression of Pph2 and GS in E. coli and Purification

For the overexpression of Pph2 and glutamine synthetase (GS) in E. coli, the two genes were PCR-amplified with the primer pairs pTOP-Pph2/pTop2-Pph2R and pETTopo2-GlnF/pETTopo2-GlnR, respectively (Table 2), and the PCR products were cloned into the vector pET200/D-TOPO (Invitrogen). The resulting plasmids were used to transform the expression strain E. coli BL21 Star (DE3). The transformed cells were grown in LB medium containing 100 μg/ml kanamycin at 37 °C until the A600 reached 0.5–0.7. Fifteen minutes before induction, the flasks were shifted to 15 °C. Induction was performed by the addition of 1 mm of isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Induced cultures were incubated with shaking at 15 °C for 3 h in the case of Pph2, whereas an 8-h incubation period was used for GS before the cells were harvested. Recombinant proteins were purified using the HisTrap Kit (Amersham Biosciences). Briefly, 10 liters of induced cultures were centrifuged, and the bacterial pellets were resuspended in 3 ml of binding buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mg/ml lysozyme) per gram of cells. These concentrated samples were incubated at 30 °C for 15 min in the presence of 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 mm benzamidine, sonicated, and cleared by centrifugation. The supernatants were then passed through a 0.45-μm filter and supplemented with 10 mm imidazole, pH 7.4. Next, the samples were treated as indicated by the protocol of the HisTrap kit. Finally, the proteins were eluted with a buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, plus 0.5 m NaCl) containing 40, 60, 100, 300, or 500 mm imidazole. To confirm that the purified proteins were correct, these fractions were separated by 12.5% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose for Western blotting. The primary antibody used was Anti-His G-AP from Invitrogen, which specifically recognizes the His tag added to the proteins. Fractions eluting with 300 mm imidazole were used in this work.

Determination of Phosphatase and γ-Glutamylamide Synthetase Activities

When phosphatase activity was determined by using p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) as substrate, the purified enzyme (200 ng) was added to a mixture containing 50 mm buffer (sodium acetate, pH 5.2; imidazole, pH 6.5; or Tris-HCl, pH 8.0), 5 mm metals (MnCl2, MgCl2, or Ni(NO3)2), and 10 mm pNPP in a 200-μl final volume, as already reported (18). The release of p-nitrophenol (pNP) was determined spectrophotometrically at 410 nm. Specific activity is expressed as picomoles of pNP produced per minute and μg of protein. On the other hand, the phosphopeptides RRA(pT)VA, END(pY)INASL, and DADE(pY)LIPQQG were added as substrates to the same buffers and metals combinations described above, and the phosphatase activities were assayed according to the instructions of the serine/threonine or tyrosine assay systems supplied by Promega (Madison, WI). Specific activity is expressed as picomoles of phosphate released per minute and μg of protein.

GS was tested for γ-glutamylamide synthetase activity by following the method described by de Azevedo Wäsch et al. (25), which uses l-glutamate, isopropylamine, and ATP as substrates. The purified enzymes or the cell extracts (200 ng each) were added to the reaction mixtures (final volume, 200 μl), and incubated at 30 °C for 15 min. The activity was expressed as nanomoles of inorganic phosphate released per ml of reaction.

Construction of an M. xanthus Library for Yeast Two-hybrid Screen with Pph2

An M. xanthus library was generated to harbor genomic fragments fused to the GAL4 activation domain using the Matchmaker Two-Hybrid System (Clontech) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. Briefly, genomic DNA was partially digested with AciI, HinP1I, or MspI, and 0.5- to 3.0-kb fragments were isolated and ligated to ClaI-digested pGAD-C1, -C2, and -C3 vectors (Table 1), which contain a unique ClaI site in the three different reading frames, ensuring the expression of each inserted fragment in-frame with the GAL4 activation domain (26). The library was electroporated and amplified in E. coli DH10B, obtaining around 5 × 107 independent clones. Plasmids were isolated in three different pools by the method described by Robzyk and Kassir (27), and it was confirmed that at least 98% of the isolated vectors contained genomic DNA fragments inserted.

The gene pph2 was amplified by PCR using the primers Pph2Eco2HF-Pph2Pst2HR (Table 2) and M. xanthus chromosomal DNA as template and cloned into plasmid pGBKT7 previously digested with EcoRI and PstI. Restrictions sites were designed to fuse in-frame Pph2 with the GAL4 DNA-binding domain. The resulting bait plasmid pGBKT7-Pph2 was used to transform the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae AH109 (Table 1) using the high efficiency lithium acetate method (28). Selection of yeasts harboring this plasmid was carried out in the minimal medium SD Trp− at 30 °C (29). One positive colony was isolated to be transformed with the prey plasmid pools from the library, and the transformants were selected on SD Trp−Leu−His− medium. The total number of colonies screened was ∼5 × 105. Colonies able to grow on this medium were further screened on SD Trp−Leu−His−Ade− medium, and their β-galactosidase activity was quantified. Target plasmids from positive colonies were isolated, and their sequences were obtained using the primer pGADSecF, which anneals within the pGAD vectors (Table 2).

Chemicals

All the chemicals were purchased from Sigma, and restriction enzymes were from Roche Applied Science. The exceptions are indicated in parentheses the first time that the compound is listed.

RESULTS

Analysis of the Pph2 Sequence and Expression of the Gene

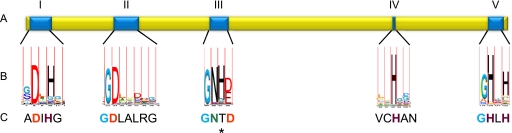

The analysis of the region where the TCS phoPR1 is encoded (MXAN_4777 and MXAN_4778) has revealed the presence of a gene (MXAN_4779) that codes for a protein of 314 amino acids, exhibiting similarities to bacterial PPs of the family PPP such as PrpA from Salmonella typhimurium (30), and PrpA and PrpB from E. coli (9). However, the identity with these proteins was only 14.9%, 14.8%, and 13.2%, respectively. Despite the low similarities with these other bacterial PPs, M. xanthus protein contains all the conserved residues (with the exception of one) that define the calcineurin-like phosphoesterase family (PF00149), also designated as metallophosphatase, which are present in protein Ser/Thr phosphatases of the family PPP (Fig. 1). Therefore, we have named this protein as Pph2. The analysis of the sequence at the TMHMM server (transmembrane prediction by using hidden Markov models) revealed that Pph2 does not contain transmembrane helices, indicating that it is located in the cytoplasm.

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the protein phosphatase Pph2 from M. xanthus. A, position of the five conserved domains of PPP protein phosphatases in Pph2. B, the logo depicted under each domain represents the more conserved residues for this protein family. C, the sequence corresponding to Pph2 has been written under each logo. The asterisk represents the change in Pph2 of the conserved His by a Thr.

As pph2 is positioned just downstream of phoR1, at a distance of only 12 bp, and it is encoded in the same orientation as phoPR1, we analyzed whether these three genes were coexpressed by using RT-PCR. The strategy followed is depicted in Fig. 2A. As shown in Fig. 2B, all the reactions amplified one fragment with the expected size (Fig. 2B, lanes 3–5), with the exception of the negative control, in which RNA not subjected to RT, was used as a template (Fig. 2B, lane 2). This result indicates that the genes pph2, phoR1, and phoP1 form part of the same operon. Nevertheless, to corroborate this result, an M. xanthus strain harboring a fusion between the first codon of pph2 and lacZ from E. coli was constructed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” β-Galactosidase activity in the strain thus obtained was determined on rich and starvation media. As observed in Fig. 2C, pph2 is expressed at high levels during growth, but its expression peaks upon starvation. This expression profile is coincident to that previously reported for phoPR1 (18), demonstrating that the three genes are indeed coregulated.

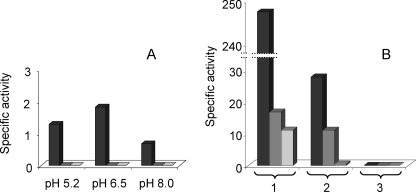

Pph2 Is a Mn2+-dependent Neutral Phosphatase

As mentioned above, Pph2 contains all the residues required for the dephosphorylation of protein substrates with the exception of one, the His of subdomain III, which is substituted by a Thr (Fig. 1). As this residue has been reported to be essential for the activity of other PPP phosphatases (31, 32), the possibility exists that the M. xanthus protein were inactive. To demonstrate phosphatase activity, Pph2 was overexpressed in E. coli with a His tail at the N terminus to facilitate the purification process and the identification of the protein by Western blot (see “Experimental Procedures”). The purified recombinant Pph2 protein was used to determine phosphatase activity against four different substrates: pNPP, a universal substrate for phosphatases; one phosphopeptide specific for phosphoserine/threonine phosphatases; and two phosphopeptides specific for phosphotyrosine phosphatases. The dependence on pH and metals, which often varies among phosphatases, was evaluated in all the assays. The results obtained indicated that Pph2 exhibited very low activity against pNPP. This activity was higher in the presence of Mn2+ and at neutral pH (Fig. 3A). No activity was detected against the peptide END(pY)INASL in any of the conditions tested (Fig. 3B). On the contrary, dephosphorylation of the other two phosphopeptides was observed (Fig. 3B), being more efficient the activity against phosphothreonine than against phosphotyrosine. The activity against these two phosphopeptides was also higher at neutral than at acidic or basic pHs (data not shown). All these results are coincident and confirm that Pph2 holds Mn2+-dependent protein phosphatase activity, with a higher specificity against phosphoserine/threonine residues.

FIGURE 3.

Pph2 is a Mn2+-dependent neutral protein phosphatase.A, phosphatase activity of Pph2 on pNPP in the presence of the divalent metals Mn2+ (dark gray columns), Mg2+ (medium gray columns), and Ni2+ (light gray columns) at acidic, neutral, and basic pHs. B, dephosphorylation of the peptides RRA(pT)VA (1), DADE(pY)LIPQQG (2), and END(pY)INASL (3) by Pph2 in the presence of Mn2+, Mg2+, and Ni2+ at pH 6.5. The color code shown for the metals is the same as in panel A. Please note the difference in scale between the two panels. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

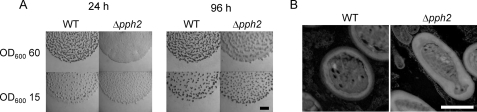

Pph2 Is Involved in Aggregation, Sporulation, and Germination

To study the role of pph2 in the life cycle of M. xanthus, an in-frame deletion mutant for this gene was constructed. No differences were observed when both mutant and the WT strain were cultured in rich liquid medium CTT. Thus, generation times and maximum cell densities reached at the stationary phase were identical in these two strains (data not shown). On the contrary, when the phenotype of the Δpph2 mutant was analyzed during development on CF medium, a delay in aggregation was observed, which was especially marked when cells were plated at an A600 of 60 (Fig. 4A). In these conditions, the mutant formed aggregates that remained immature even after 96-h incubation. Accordingly, the yield of myxospores was lower in the mutant (75% ± 7.8 of the spores originated by the WT strain). In addition, when myxospores were examined by TEM we found that roughly 12% did not reshape completely and did not become ovoid, although they were covered with a thick coat similar to that of the WT strain (Fig. 4B). Moreover, the mutant was clearly affected in germination, and only 2.1% ± 0.83 of the myxospores were able to originate colonies in rich medium, versus the 7.5% ± 1.5 that germinated in the WT strain.

FIGURE 4.

Phenotypical analysis during development of the WT strain and the Δpph2 mutant. A, morphology of fruiting bodies. Cells were concentrated at an A600 of 15 and 60, and spotted onto CF medium. Bar represents 0.5 mm. B, morphology of WT strain and Δpph2 mutant myxospores; the pictures were taken by TEM. Bar represents 1 μm.

Effect of CCCP on ΔphoPR1 and Δpph2 Mutants

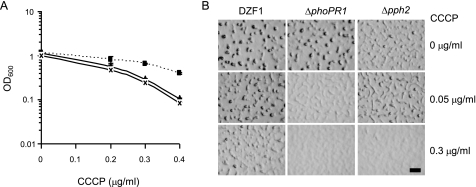

Several findings regarding the operon phoPR1-pph2 indicated that it could be implicated in the regulation of M. xanthus energy metabolism, especially during development. First, the histidine kinase PhoR1 contains a cytoplasmic PAS-4-fold (PF08448), which seems to sense the overall energy level of the cell (33, 34). Second, the PhoPR1 TCS partially regulates the expression of this operon (18). And third, aggregation of the Δpph2 mutant is highly dependent on the cell density and, therefore, on the nutrient concentration available for each developing cell, what will diminish their energy levels (Fig. 4A). The reduction in energy levels of the cells can be induced by the addition of chemical compounds, such as the protonophore CCCP, which dissipates the proton-motive force generated in the cytoplasmic membrane, provoking energy stress as the result of intracellular ATP depletion (35). To test the sensitivity of the Δpph2 mutant to CCCP during growth, the WT strain and the mutant were inoculated into liquid CTT containing several concentrations of the protonophore, and the A600 after 24-h incubation was monitored. As it can be observed in Fig. 5A, the growth of the Δpph2 strain was clearly inhibited by CCCP when compared with the WT strain. CCCP also affected development. The WT strain originated immature fruiting bodies in the presence of increasing concentrations of the protonophore. However, the mutant exhibited more severe defects, and failed to aggregate even with low CCCP concentrations (Fig. 5B). We also tested whether CCCP was able to inhibit growth and development of a ΔphoPR1 mutant. Because the mutant that was previously constructed was not in-frame (18), and therefore, the results that would be obtained might be the consequence of a polar effect on the expression of pph2, which is located just downstream of phoR1, a new mutant harboring an in-frame deletion of phoPR1 was constructed. The results obtained revealed that CCCP inhibited the growth of this mutant at a similar rate as that observed for Δpph2 (Fig. 5A). On the contrary, the effect of CCCP on development was more severe on the ΔphoPR1 mutant than on Δpph2 (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Sensitivity to CCCP of M. xanthus strains during growth and development. A, WT (dash line with squares), Δpph2 (continuous line with triangles), and ΔphoPR1 (continuous line with crosses) cells were diluted to an A600 of 0.05 in fresh CTT liquid media containing the indicated CCCP concentrations. The A600 represented in the figure was monitored after 24-h incubation. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Experiments were performed in triplicate. B, cells were concentrated to an A600 of 15 and spotted onto CF medium containing CCCP. Pictures were taken after 24-h incubation. Bar represents 1 mm.

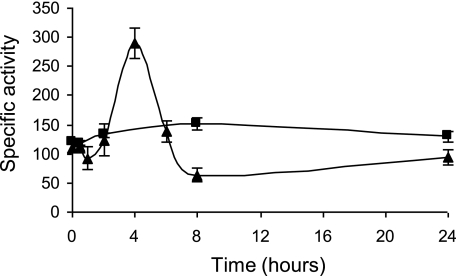

These results prompted us to test whether CCCP, in addition to starvation, was able to induce the expression of the phoPR1-pph2 operon. For this experiment, we quantified the expression of the operon during growth in medium CTT supplemented with a CCCP concentration of 0.6 μg/ml. The results obtained revealed that expression of pph2-lacZ increased by the addition of the protonophore, exhibiting a peak after 4-h incubation (Fig. 6). The levels of expression obtained with CCCP were similar to those observed during development (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 6.

Up-regulation of pph2 expression by CCCP during growth. β-Galactosidase-specific activity of the pph2-lacZ strain grown in CTT medium without CCCP is represented by squares, while the activity exhibited by this strain in the same medium containing 0.6 μg/ml of CCCP is represented by triangles. Error bars indicate standard deviations. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

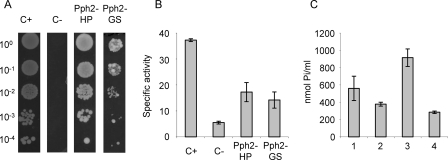

Yeast Two-hybrid Library Screening Using Pph2 as Bait

To find proteins that interact with Pph2, a yeast two-hybrid M. xanthus library was constructed and screened with the complete Pph2 as bait. Two proteins were identified as potential interactors, encoded by the gene identifiers MXAN_1875 and MXAN_5630 (Fig. 7A). The first one encodes a hypothetical protein (HP) only found in other myxobacteria. The second one encodes a protein that exhibits high similarities to GS, such as IpuC from Pseudomonas sp. strain KIE171 (25), with which it shares 39% identity and 59% homology if functionally similar amino acids are considered. Furthermore, this protein perfectly matches the catalytic domain of GS defined in Pfam (PF00120), with an E value of 9.8e-86.

FIGURE 7.

Interaction between Pph2 and the gene products of MXAN_1875 (HP) and 5630 (GS) by yeast two-hybrid screen. Yeasts provided in the kit were used as positive and negative controls (Table 1). A, yeasts were grown to mid-log phase in SD Trp−Leu− medium, washed in this medium, and concentrated to an A600 of 1. Finally, 10-μl drops of serially diluted 10-fold suspensions were spotted onto SD Trp−Leu−His−Ade− agar plates and incubated for 5 days. B, quantification of the interactions by β-galactosidase activity determinations. Experiments were performed in triplicate. C, γ-glutamylamide synthetase activity of the purified GS when incubated alone (1), in the presence of purified Pph2 (2), cell extracts from the Δpph2 mutant (3), or purified Pph2 plus cell extracts from the Δpph2 mutant (4). In each assay, a reaction mixture where only GS was omitted was used as a blank. Error bars indicate standard deviations. These experiments were also performed in triplicate.

The interactions were quantified by assaying the β-galactosidase activity. Pph2 is associated with HP and GS with a moderate efficiency, exhibiting activities of 17 and 14 units, respectively, versus 5 units detected with the negative control (Fig. 7B). The results obtained with the β-galactosidase activities correlate well with the growth profiles of the serially diluted spots shown in Fig. 7A. To validate the interaction, GS was expressed in E. coli, and the purified protein was assayed for γ-glutamylamide synthetase activity, because some GS, such as IpuC, incorporate amines from organic compounds into glutamate to synthesize γ-glutamylamides rather than ammonium to originate glutamine (25). The M. xanthus protein could efficiently synthesize γ-glutamylisopropylamide (Fig. 7C, bar 1). This activity decreased in the presence of Pph2 (Fig. 7C, bars 2 and 4), whereas increased after supplementation of the reaction with cell extracts obtained from the Δpph2 mutant (Fig. 7C, bar 3). This result indicates that Pph2 interacts with GS and inhibits the γ-glutamylamide synthetase activity of the enzyme.

DISCUSSION

The complex life cycle of M. xanthus requires the coordination of a large number of cells, which must act together to feed cooperatively and to build up multicellular fruiting bodies. This social behavior is orchestrated by signal-transduction mechanisms, which comprise both TCSs and ELKs/PPs. In fact, an elevated number of paralogous genes involved in signal transduction have been reported not only in M. xanthus genome (36), but also in other myxobacterial genomes, such as the one of Sorangium cellulosum (37). Actually, myxobacteria encode the largest number of ELKs among the prokaryotes and seem to correlate with their multicellular behavior (4). Additionally, M. xanthus genome encodes 34 PPs, 25 of which belong to the PPP family (3). Although several M. xanthus ELKs have been so far characterized (3), most of which have been involved in development, only the PP of the PPM family Pph1 has been studied in detail (17). Here, we have focused our attention on the PP of the PPP family designated as Pph2. This phosphatase exhibits all the sequence motifs implicated in metal binding and catalysis (31, 32, 38, 39) with the only exception of the conserved His from subdomain III, which is substituted by a Thr in the M. xanthus protein. However, our biochemical characterization of the purified Pph2 has unambiguously demonstrated that the protein is active, with specificity for phosphorylated Ser/Thr residues rather than for Tyr. Nevertheless, the scarce activity on the universal substrate for phosphatases pNPP could be attributed to this substitution in subdomain III.

The main reason to study Pph2 was the fact that it is encoded in the vicinity of the TCS PhoPR1, which has been previously characterized in our laboratory. This TCS is required for M. xanthus development, because it is induced upon starvation, and a deletion mutant exhibits defects in aggregation and diminished levels of expression of its own operon and of phosphatase activities, which are induced only during development (18). Now, we have also demonstrated that phoPR1 and pph2 are cotranscribed.

All the previous studies on the TCS PhoPR1 shed some clues on the physiological role that Pph2 could fulfill. The modular organization of the histidine kinase PhoR1, with a PAS-4-fold located in the cytoplasm, along with the induction of the operon by nutrient limitation, led us to think that Pph2 could contribute to provide sufficient energy to M. xanthus cells to ensure the completion of development. It must be reminded that developing cells have to glide to the aggregation centers, change their expression profile, and reshape from long rods to coccoid myxospores. All these events last more than 24 h and occur under nutrient depletion, so cells must optimize the scarce energy resources to successfully complete the cycle. Several of the results we have obtained during this work support that Pph2 indeed exerts this function: (i) the Δpph2 mutant exhibits defects on aggregation, which are more severe at higher cell densities; (ii) a significant portion of the mutant myxospores fails to properly reshape; (iii) the yield of myxospores and their ability to germinate were diminished in the mutant; (iv) the addition of CCCP drastically reduces the viability of the mutant cells and inhibits development; and (v) starvation and CCCP induce the expression of the operon phoPR1-pph2. To our knowledge, only the PP RsbP from Bacillus subtilis has been also implicated in response to energy stress (40). In this case, a PAS domain is located at the N-terminal region of RbsP, which seems to be responsible for sensing redox potential to control the adaptive response.

All the data presented here allowed us to create a working model, in which PhoR1 would sense the energy depletion occurred in the cells during starvation, activating the cognate response regulator PhoP1. This activation would induce the expression of its own operon, of Mg2+-independent phosphatases, and most likely of other genes that are still to be determined, several of which could be involved in energy metabolism. Simultaneously, the levels of Pph2 would also increase in the cells, dephosphorylating protein substrates that will alter their activity by this post-translational modification. These proteins might also be involved in energy metabolism. The synergic effect of PhoP1 and Pph2 would make the cells more proficient in using the scarce energy supply to originate mature fruiting bodies filled of myxospores.

In B. subtilis and E. coli, phosphoproteomic studies have revealed that most of the identified phosphoproteins participate in a variety of metabolic processes, with the highest proportion involved in the glycolytic pathway and in the tricarboxylic acid cycle (41, 42). Moreover, a preliminary analysis of the phosphoproteome from the myxobacteria S. cellulosum reported that over 40% of the proteins are phosphorylated, 57% of which are involved in metabolism (37). Although M. xanthus phosphoproteome has not been analyzed yet, it has been shown that the ELK Pkn4 participates in energy metabolism during development. This kinase phosphorylates the glycolytic enzyme phosphofructokinase. This phosphorylation event increases the enzymatic activity and allows developing cells to consume the glycogen accumulated during growth to generate ATP (43, 44). However, Pph2 does not seem to be the PP with the ability to revert the action of Pkn4, because the phosphofructokinase activity would decrease in this situation, preventing the cells from obtaining energy. The results obtained by using the yeast two-hybrid system have shown that Pph2 interacts with an HP and a GS. Nevertheless, it remains unknown whether the activities of these two proteins are regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation and their role in energy metabolism. The fact that the γ-glutamylamide synthetase activity of GS increases in the presence of a cell extract obtained from the Δpph2 mutant and decreases in the presence of purified Pph2 indicates that this post-translational modification most likely will be responsible for the regulation of the activity of this protein. Undoubtedly, the identification of all the genes that are under control of PhoP1 and the substrate proteins for Pph2 will help to elucidate the intriguing question of how M. xanthus complete development under conditions of nutrient depletion.

This work was supported in part by grants from Junta de Andalucía (CVI-1377) and Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología (BMC2003-02038 and BFU2006-00972/BMC), Spain. The yeast two-hybrid library was constructed under the supervision of Montserrat Elías-Arnanz during a short term stay of A. C.-G. at the University of Murcia, granted by Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología.

- ELK

- eukaryotic-like protein kinase

- PP

- protein phosphatase

- WT

- wild type

- TCS

- two-component system

- RT

- reverse transcription

- CCCP

- carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone

- TEM

- transmission electron microscopy

- pNPP

- p-nitrophenyl phosphate

- pNP

- p-nitrophenol

- X-gal

- 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside

- PPP

- phosphoprotein phosphatase

- PPM

- Mn2+- or Mg2+-dependent protein phosphatase

- HP

- hypothetical protein

- GS

- glutamine synthetase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Whitworth D. E. (2008) Myxobacteria. Multicelullarity and Differentiation, ASM Press, Washington, D. C. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitworth D. E., Cock P. J. (2008) in Myxobacteria. Multicellularity and Differentiation (Whitworth D. E. ed) pp. 169–189, ASM Press, Washington, D. C. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inouye S., Hirofumi N., Muñoz-Dorado J. (2008) in Myxobacteria. Multicellularity and Differentiation (Whitworth D. E. ed) pp. 191–210, ASM Press, Washington, D. C. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pérez J., Castañeda-García A., Jenke-Kodama H., Müller R., Muñoz-Dorado J. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 15950–15955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duncan L., Alper S., Arigoni F., Losick R., Stragier P. (1995) Science 270, 641–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cozzone A. J., Grangeasse C., Doublet P., Duclos B. (2004) Arch. Microbiol. 181, 171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi L., Potts M., Kennelly P. J. (1998) FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 22, 229–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen P. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 201, 389–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Missiakas D., Raina S. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 1670–1685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang C. C., Friry A., Peng L. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 2616–2622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mai B., Frey G., Swanson R. V., Mathur E. J., Stetter K. O. (1998) J. Bacteriol. 180, 4030–4035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Umeyama T., Naruoka A., Horinouchi S. (2000) Gene 258, 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwanicki A., Herman-Antosiewicz A., Pierechod M., Séror S. J., Obuchowski M. (2002) Biochem. J. 366, 929–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang W., Shi L. (2004) Microbiology 150, 4189–4197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberg R. A., Zusman D. R. (1990) J. Bacteriol. 172, 2294–2302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitworth D. E., Holmes A. B., Irvine A. G., Hodgson D. A., Scanlan D. J. (2008) J. Bacteriol. 190, 1997–2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Treuner-Lange A., Ward M. J., Zusman D. R. (2001) Mol. Microbiol. 40, 126–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carrero-Lérida J., Moraleda-Muñoz A., García-Hernández R., Pérez J., Muñoz-Dorado J. (2005) J. Bacteriol 187, 4976–4983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moraleda-Muñoz A., Carrero-Lérida J., Pérez J., Muñoz-Dorado J. (2003) J. Bacteriol. 185, 1376–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sambrook J., Russell D. W. (2001) Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 3rd Ed., Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashefi K., Hartzell P. L. (1995) Mol. Microbiol. 15, 483–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cho K., Zusman D. R. (1999) Mol. Microbiol. 34, 268–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Julien B., Kaiser A. D., Garza A. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9098–9103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez-Cañamero M., Ortiz-Codorniu C., Extremera A. L., Muñoz-Dorado J., Arias J. M. (2003) Anton Leeuw Int. J. G. 83, 361–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Azevedo Wäsch S. I., van der Ploeg J. R., Maire T., Lebreton A., Kiener A., Leisinger T. (2002) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 2368–2375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James P., Halladay J., Craig E. A. (1996) Genetics 144, 1425–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robzyk K., Kassir Y. (1992) Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schiestl R. H., Gietz R. D. (1989) Curr. Genet. 16, 339–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaiser C., Michaelis S., Mitchell A. (1994) Methods in Yeast Genetics, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi L., Kehres D. G., Maguire M. E. (2001) J. Bacteriol. 183, 7053–7057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Voegtli W. C., White D. J., Reiter N. J., Rusnak F., Rosenzweig A. C. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 15365–15374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jackson M. D., Denu J. M. (2001) Chem. Rev. 101, 2313–2340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor B. L., Zhulin I. B. (1999) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63, 479–506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watts K. J., Sommer K., Fry S. L., Johnson M. S., Taylor B. L. (2006) J. Bacteriol. 188, 2154–2162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor B. L. (1983) Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 37, 551–573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldman B. S., Nierman W. C., Kaiser D., Slater S. C., Durkin A. S., Eisen J. A., Eisen J., Ronning C. M., Barbazuk W. B., Blanchard M., Field C., Halling C., Hinkle G., Iartchuk O., Kim H. S., Mackenzie C., Madupu R., Miller N., Shvartsbeyn A., Sullivan S. A., Vaudin M., Wiegand R., Kaplan H. B. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15200–15205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneiker S., Perlova O., Kaiser O., Gerth K., Alici A., Altmeyer M. O., Bartels D., Bekel T., Beyer S., Bode E., Bode H. B., Bolten C. J., Choudhuri J. V., Doss S., Elnakady Y. A., Frank B., Gaigalat L., Goesmann A., Groeger C., Gross F., Jelsbak L., Jelsbak L., Kalinowski J., Kegler C., Knauber T., Konietzny S., Kopp M., Krause L., Krug D., Linke B., Mahmud T., Martinez-Arias R., McHardy A. C., Merai M., Meyer F., Mormann S., Muñoz-Dorado J., Perez J., Pradella S., Rachid S., Raddatz G., Rosenau F., Rückert C., Sasse F., Scharfe M., Schuster S. C., Suen G., Treuner-Lange A., Velicer G. J., Vorhölter F. J., Weissman K. J., Welch R. D., Wenzel S. C., Whitworth D. E., Wilhelm S., Wittmann C., Blöcker H., Pühler A., Müller R. (2007) Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 1281–1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barton G. J., Cohen P. T., Barford D. (1994) Eur. J. Biochem. 220, 225–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhuo S., Clemens J. C., Stone R. L., Dixon J. E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26234–26238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vijay K., Brody M. S., Fredlund E., Price C. W. (2000) Mol. Microbiol. 35, 180–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macek B., Mijakovic I., Olsen J. V., Gnad F., Kumar C., Jensen P. R., Mann M. (2007) Mol. Cell Proteomics 6, 697–707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macek B., Gnad F., Soufi B., Kumar C., Olsen J. V., Mijakovic I., Mann M. (2008) Mol. Cell Proteomics 7, 299–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nariya H., Inouye S. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 46, 1353–1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nariya H., Inouye S. (2003) Mol. Microbiol. 49, 517–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanisch-Perron C., Vieira J., Messing J. (1985) Gene 33, 103–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Morrison C. E., Zusman D. R. (1979) J. Bacteriol. 140, 1036–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]