Abstract

SMILE (small heterodimer partner interacting leucine zipper protein) has been identified as a corepressor of the glucocorticoid receptor, constitutive androstane receptor, and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α. Here we show that SMILE also represses estrogen receptor-related receptor γ (ERRγ) transactivation. Knockdown of SMILE gene expression increases ERRγ activity. SMILE directly interacts with ERRγ in vitro and in vivo. Domain mapping analysis showed that SMILE binds to the AF2 domain of ERRγ. SMILE represses ERRγ transactivation partially through competition with coactivators PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and GRIP1. Interestingly, the repression of SMILE on ERRγ is released by SIRT1 inhibitors, a catalytically inactive SIRT1 mutant, and SIRT1 small interfering RNA but not by histone protein deacetylase inhibitor. In vivo glutathione S-transferase pulldown and coimmunoprecipitation assays validated that SMILE physically interacts with SIRT1. Furthermore, the ERRγ inverse agonist GSK5182 enhances the interaction of SMILE with ERRγ and SMILE-mediated repression. Knockdown of SMILE or SIRT1 blocks the repressive effect of GSK5182. Moreover, chromatin immunoprecipitation assays revealed that GSK5182 augments the association of SMILE and SIRT1 on the promoter of the ERRγ target PDK4. GSK5182 and adenoviral overexpression of SMILE cooperate to repress ERRγ-induced PDK4 gene expression, and this repression is released by overexpression of a catalytically defective SIRT1 mutant. Finally, we demonstrated that ERRγ regulates SMILE gene expression, which in turn inhibits ERRγ. Overall, these findings implicate SMILE as a novel corepressor of ERRγ and recruitment of SIRT1 as a novel repressive mechanism for SMILE and ERRγ inverse agonist.

Estrogen-related receptors (ERRα, ERRβ, and ERRγ)2 are constitutively active nuclear receptors (NRs) that contain high levels of sequence identity to estrogen receptors (ERs) (1). All the ERR family members bind either as a monomer or a homodimer or as heterodimeric complexes composed of two distinct ERR isoforms to the consensus sequence TCAAGGTCA, referred to as ERR-response element (ERRE), and as homodimers to the consensus estrogen-responsive element (1–3). Together with ERRα and ERRβ, ERRγ regulates a number of genes involved in energy homeostasis, cell proliferation, and cancer metabolism (3, 4). Targets of ERRγ known to date are PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1α), PDK4 (pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoform 4), retinoic acid receptor α, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 (WAF1/CIP1) and p27 (KIP1) (4–7). The ability of ERRγ to regulate target gene transcription relies on its interaction with coactivators and corepressors. The coactivators GRIP1 (glucocorticoid receptor interacting protein 1), PGC-1α, and corepressors small heterodimer partner (SHP), DAX-1, and RIP140 (receptor interacting protein 140) or NRIP1 have been reported to modulate ERRγ activity (5, 8–11). In addition, 4-hydroxytamoxifen and its derivative GSK5182 act as inverse agonists for ERRγ (12–14). However, the deactivation mechanisms by these inverse agonists remain unclear.

SMILE (small heterodimer partner interacting leucine zipper protein), including two alternative translation-derived isoforms, SMILE-L (CREBZF; long form of SMILE) and SMILE-S (Zhangfei; short form of SMILE), has been classified as a member of the CREB/ATF family of basic region-leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors (15, 16). However, SMILE cannot bind to DNA as homodimers, although it can homodimerize like other bZIP proteins (15, 17). SMILE has been implicated in herpes simplex virus infection cycle and related cellular processes through its association with herpes simplex virus-related host-cell factor and CREB3 (17, 18). SMILE has also been proposed as a coactivator of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4/CREB2) (19). Recently, we have reported that SMILE functions as a coregulator of ER signaling and a corepressor of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α (HNF4α) (16, 20). However, the detailed roles of SMILE on other NRs still need to be clarified.

Silent information regulator 2 proteins (Sirtuins) are class III histone protein deacetylases (HDACs) and consist of seven members named SIRT1 to SIRT7 in mammals (21). Through deacetylating target proteins, Sirtuins play important roles in cellular processes such as gene expression, apoptosis, metabolism, and aging (21). Of the seven Sirtuins, SIRT1 has been extensively studied. It has been reported that SIRT1 deacetylates and thereby deactivates the p53 and PARP1 protein (poly(ADP ribose) polymerase-1), resulting in promoted cell survival (22, 23). In addition, SIRT1 regulates glucose or lipid metabolism through its deacetylation activity on over 24 known substrates, including FOXO transcriptional factors (24, 25) PPARα (26), PPARγ (27), and PGC-1α (28). It has also been demonstrated that SIRT1 regulates cholesterol metabolism through deacetylation and activation of liver X receptor proteins (29).

In this study, we have shown that SMILE negatively regulates ERRγ through direct interaction. We have demonstrated that coactivator competition and recruitment of catalytically active SIRT1 are required for the repression of ERRγ by SMILE. Moreover, ERRγ-specific inverse agonist GSK5182 enhances the interaction of SMILE and ERRγ. siRNA SMILE and siRNA SIRT1 experiments have revealed that SMILE-SIRT association is required for the inhibition of ERRγ by GSK5182. In addition, we have observed that ERRγ induces SMILE gene expression in HepG2 cells by directly binding to the SMILE promoter and that SMILE inhibits ERRγ transactivation of its own promoter. Overall, our observations suggest that SMILE acts as a novel corepressor of ERRγ and that ERRγ belongs to a new autoregulatory loop that governs SMILE gene expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid and DNA Construction

The plasmids of pCMV-β-gal, pcDNA3-ERRα, -ERRβ, -ERRγ, -ERRγΔAF2, pSG5-HA-ERRγ, pGEX4T-1-ERRγ, and sft4-Luc were described elsewhere (9, 10). (HNF4)8-tk-Luc, pcDNA3-HA-HNF4α, -PGC-1α, pSG5-HA-GRIP1, pcDNA3-SMILE, -FLAG-SMLE, -SMILE-83Leu, -SMILE-1Phe, pGEX4T-1, pGEX4T-1-SMILE, pEGFP-SMILE, pEBG, pEBG-SMILE, and pEBG-SMILE deletion constructs SMILE-L(239–267)V, pSUPER, pSUPER-siSHP, -siSMILE-I, and -siSMILE-II were described previously (2). pcDNA3- FLAG-SIRT6 and -SIRT7 were kindly provided by Dr. Eric Verdin (30). pcDNA3-HA-PGC-1β, -FLAG-FOXO1, and the reporter PDK4-Luc were kind gifts from Drs. Dieter Kressler (31), Akiyoshi Fukamizu (32), and Robert A. Harris (33), respectively.

pcDNA3-FLAG-ERRα and -ERRβ were constructed by inserting the full PCR fragments of the open reading frames into the EcoRI/XhoI sites of pcDNA3-FLAG.pcDNA3- FLAG-ERRγ was generated via subcloning the full open reading frame of ERRγ into the EcoRV/XhoI sites of the pcDNA3-FLAG vector. pcDNA3-myc-SIRT1 was constructed via inserting the open reading frame of SIRT1 into pcDNA3-myc vector. pcDNA3-myc-SIRT1H363Y was generated via PCR-mediated site-directed mutagenesis. pSUPER-siSIRT1 was constructed by inserting a 64-bp double-stranded oligonucleotide containing 5′-GAAGTTGACCTCCTCATTGT-3′ of the human SIRT1 cDNA sequence into the pSUPER vector between BglII and XhoI sites. To generate −1131-bp-SMILE-Luc, the SMILE promoter region spanning −1131 to −15 bp was PCR-amplified from human genomic DNA and cloned into pGL3-basic vector (Promega) between the SacI and XhoI sites. −879-bp- and −448-bp-SMILE-Luc were constructed by inserting the PCR fragments into the SacI/XhoI sites of pGL3-basic vector. The mutant reporters of SMILE-mtERRE1-Luc and SMILE-mtERRE2-Luc were subcloned via site-directed mutagenesis from −1131-bp-SMILE-Luc. The mutated sequences are shown in Fig. 7D. All plasmids were confirmed via sequencing analysis.

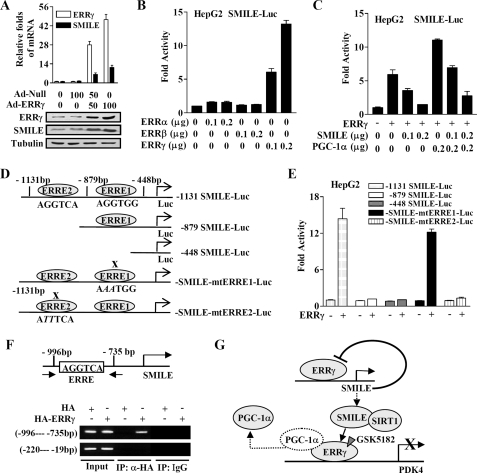

FIGURE 7.

Autoregulatory loop controlling SMILE gene expression by ERRγ. A, upper panel shows the relative ERRγ and SMILE mRNA levels analyzed by quantitative real time PCR (standardized using β-actin). Normalized basal levels of each transcript were assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0 for comparison. Lower panel shows the protein expression levels of ERRγ and SMILE. Tubulin was used as a loading control. HepG2 cells were infected with adenovirus vector (Ad-Null and Ad-ERRγ) at indicated multiplicity of infection (0, 50, or 100). B, ERRγ activates human SMILE promoter activity. HepG2 cell were cotransfected with 0.1 μg of SMILE-Luc reporter vector and indicated amount of expression vectors encoding ERRα, ERRβ, or ERRγ. C, SMILE inhibits ERRγ-mediated and PGC-1α-enhanced SMILE promoter activity. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 0.2 μg of SMILE-Luc reporter together with or without 0.2 μg of ERRγ expression vector and indicated amount of expression plasmids for SMILE and PGC-1α. D, schematic representation of wild-type and mutant hSMILE promoter constructs. The putative ERRγ binding sites are shown, and the mutated ERRE is indicated with X. E, ERRE2 is essential for the activation of SMILE promoter by ERRγ. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 0.2 μg of wild-type or mutant SMILE promoter constructs along with or without 0.2 μg of ERRγ expression vector. Luciferase activity was measured 48 h after transfection. F, ERRγ binds to SMILE promoter in ChIP assays. HepG2 cells were transfected with expression vector for HA or HA-ERRγ. Chromatin fragments were prepared from the transfected cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody or unrelated immunoglobin G (IgG) as indicated. DNA fragments covering ERRE (−996 to −735 bp) on SMILE promoter and a control region (−220 to −19 bp) were PCR-amplified. Data shown are representative of three experiments. G, schematic representation of the autoregulatory loop controlling the expression of SMILE by ERRγ and the mechanisms of SMILE repression on ERRγ, recruitment of SIRT1 and dissociation of coactivator PGC-1α.

Chemicals and Antibodies

SIRT1 inhibitors nicotinamide and sirtinol were from Calbiochem; EX527 was purchased from TOCRIS; ERRγ inverse agonist GSK5182 was synthesized according the method described previously (14), and other chemicals were from Sigma. Antibodies used in this work were as follows: anti-FLAG M2 (catalog number 200472-21, Stratagene), anti-HA (12CA5, Roche Applied Science), anti-SMILE (catalog number ab28700, Abcam), anti-GST (sc-33614, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-PGC-1α (H300, sc-13067, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-SIRT1 (catalog number 2493, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-acetyl-histone H3 (Lys-9) (catalog number 9671, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-acetylated lysine (catalog number 9441, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Myc (catalog number 2276, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-tubulin (catalog number 2146, Cell Signaling Technology), and anti-ERRγ antibodies (catalog number pph6812-00, R & D Systems). The primary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1000 in Western blot analysis and at a dilution of 1:200 in immunoprecipitation.

Cell Culture, Transient Transfection Assay, and Luciferase Assay

HEK293T (293T, human embryonic kidney), HepG2 (human hepatoma), and HeLa cells (cervical cancer) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured according to the manufacturer's instructions. Transient transfection was performed using Superfect transfection reagent (Qiagen) in 293T cells and Lipofectamine 2000 reagent (Invitrogen) in HepG2 cells. 293T and HepG2 cells were cotransfected with the reporter plasmids (HNF4)8-Luc, sft4-Luc, or PDK4-Luc coupled with various expression vectors. The plasmid of cytomegalovirus-β-galactosidase was cotransfected as an internal control, and the total DNA employed in each transfection was adjusted via the addition of an appropriate quantity of pcDNA3 vector. Approximately 36 h post-transfection, the cells were treated with or without chemicals as indicated in the figure legends for 12 h, and then cells were harvested, and the luciferase activity was measured and normalized against β-galactosidase activity as described previously (16, 20). Fold activity was calculated considering the activity of reporter gene alone as 1.

In Vitro GST Pulldown Assay and Competition Assay

In vitro GST pulldown and competition assays were performed as described previously (20). Briefly, ERR-α, -β, and -γ were labeled with [35S]methionine using a TnT in vitro translation kit (Promega), and HA-PGC-1α, -PGC-1β, and -GRIP1 were labeled with cold methionine, according to the manufacturer's instructions. GST alone and GST-fused SMILE (GST-SMILE) proteins were prepared as described previously (16). The GST proteins were prebound with glutathione-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences) and then incubated with in vitro-translated [35S]methionine-labeled ERR-α, -β, or -γ, together with or without cold methionine-labeled PGC-1α, -PGC-1β, or -GRIP1 in the binding buffer for 2–3 h at 4 °C. The beads were washed three times with the binding buffer, analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and visualized by a phosphorimage analyzer (BAS-1500, Japan).

Coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) and Western Blot Analysis

CoIP and Western blot analysis were performed as described previously (20). In Western blot analysis of immunoprecipitated proteins, conventional horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG was replaced with rabbit IgG TrueBlot (catalog number 18-8816, eBioscience) to eliminate signal interference by the immunoglobulin heavy and light chains.

In Vivo GST Pulldown Assay

In vivo GST pulldown experiments were performed as described previously (20). In brief, HepG2 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. Forty eight hours after transfection, the whole-cell extracts were prepared with 200 μl of lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mm EDTA, 0.1 m KCl, and 0.3 m NaCl) containing 0.1% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitors. Then equal amounts of total protein were used for in vivo GST pulldown assays followed by Western blot analysis.

Confocal Microscopy

The confocal microscopy assays were carried out as described previously (20). In brief, the HeLa cells grown on gelatin-coated coverslips were transfected with the indicated plasmids using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Twenty four hours after transfection, the cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde followed by immunostaining. To detect HA-tagged ERRγ and the nucleus, the cells were incubated with Alexa 594-conjugated anti-HA monoclonal antibody (1:500 dilution; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature (25 °C), washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline, and incubated with 0.1 mg/ml 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Invitrogen) solution for 10 min. After three times washing with phosphate-buffered saline, the cells were subjected to observation by confocal microscopy.

Preparation of Recombinant Adenovirus

The adenovirus encoding human SMILE or mouse ERRγ was described previously (10, 20). The adenovirus expressing SIRT1H355A was a kind gift from Dr. Myung-Kwan Han (34).

RNA Interference

Knockdown of SMILE, SHP, and SIRT1 was performed using the pSuper vector system (16, 20). 293T or HepG2 cells were transfected with siRNA constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. siRNA-treated cells were subjected to reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) or the second transfection as indicated in the figure legends.

Reverse Transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) and Quantitative Real Time PCR (qPCR) Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mRNAs of SMILE, SHP, PDK4, ERRγ, and SIRT1 were analyzed by RT-PCR or qPCR as indicated. DNA samples from total RNA reverse transcription or from chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays served as the templates for qPCR experiments, which were performed with QuantiTect SYBR GreenER PCR kit (Qiagen) and the Roter-Gene 6000 real time PCR system (Australia) in triplicate. Median cycle threshold values were determined and used for analysis. ChIP signals were presented as percentage of input signals. mRNA expression levels of the interested genes were normalized to those of β-actin. The RT-PCR and qPCR primers are provided in supplemental Table 1.

ChIP Assay

ChIP assay was performed as described previously (20). In brief, treated HepG2 cells in 60-mm culture dishes were fixed with 1% formaldehyde, washed with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, harvested, and solicited. The soluble chromatin was then subjected to immunoprecipitation using anti-ERRγ, anti-SMILE (sc-49329, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-SIRT1, anti PGC-1α, acetyl-histone H3 (Lys-9), or anti-HA antibodies followed by using protein A-agarose/salmon sperm DNA (Upstate). Unrelated IgG was used a negative control for immunoprecipitation. Precipitated DNA was recovered via phenol/chloroform extraction and amplified by qPCR or RT-PCR for 35–40 cycles using specific primer sets for the indicated specific promoter regions of PDK4 and SMILE genes. The PCR primers for ChIP assays are provided in supplemental Table 2.

Primer Extension Analysis

Transcription start site was determined by rapid amplification of cDNA ends using SMARTTM rapid amplification of cDNA ends kit (Clontech). Total RNA isolated from HepG2 cells was reverse-transcribed using SMART II A oligonucleotide and 5′-CDS primer A according to the manufacturer's recommendations. BD PowerScript RT exhibits terminal transferase activity by adding three to five residues of predominantly dC to the 3′ end of the first strand cDNA. BD PowerScript RT switches templates from RNA to BD SMART oligonucleotides, generating a complete cDNA copy of the original RNA with BD SMART sequences at the end. The dC-tailed cDNA was amplified by the BD Advantage 2 PCR system using a gene-specific primer (5′-TGGACCCCAGGCAACCGGACTGGCA-3′) corresponding to 332–356 bp of human SMILE cDNA and a nested gene-specific primer (5′-TGTTCGCTGCCCTCTGACCTGACC-3′) corresponding to 85–108 bp of human SMILE cDNA. The amplified PCR fragments were subcloned into pGEM T-easy vector (Promega) for DNA sequencing.

Statistical Analysis

Student's t test was performed using GraphPad Prism version 3.0 for Windows, and results were considered to be statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

SMILE Physically Interacts with Nuclear Receptor ERRγ Both in Vitro and in Vivo

Our previous work showed that SMILE interacted with many NRs in yeast two-hybrid interaction assays, including GR, TRα, CAR, SF-1, ERRα, ERRβ, ERRγ, HNF4α, and Nur77 (20). To further confirm the interaction of SMILE with ERRα, ERRβ, and ERRγ, in vitro and in vivo GST pulldown experiments were performed. For the in vitro GST pulldown assays, bacteria-expressed GST only or GST-SMILE proteins were incubated with in vitro translated 35S-labeled ERRα, ERRβ, or ERRγ. As shown in Fig. 1A, 35S-labeled ERRγ was observed to bind to GST-fused full-length SMILE, but 35S-labeled ERRα and ERRβ was not. These results suggest that SMILE specifically interacts with ERRγ in vitro. For the in vivo GST pulldown assays, mammalian expression vectors encoding either pEBG (GST) alone or pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE) together with pcDNA3-FLAG-ERRα, pcDNA3-FLAG-ERRβ, or pSG5-HA-ERRγ were cotransfected into HepG2 cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, HA-ERRγ was coprecipitated with GST-SMILE but not with GST alone. The expression of GST, GST-SMILE, and HA-ERRγ proteins was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B, middle and bottom panels, respectively). However, neither FLAG-ERRα nor FLAG-ERRβ was found to be coprecipitated with GST-SMILE (supplemental Fig. 1A). These results demonstrate that exogenous SMILE specifically interacts with ectopically expressed ERRγ. To further investigate whether endogenous ERRγ and SMILE can interact with each other in vivo, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed. Endogenous ERRγ proteins from HepG2 cells, mouse liver, kidney, and heart tissues were observed to be coprecipitated with SMILE (Fig. 1C). Taken together, these results validate that SMILE can specifically interact with ERRγ both in vitro and in vivo.

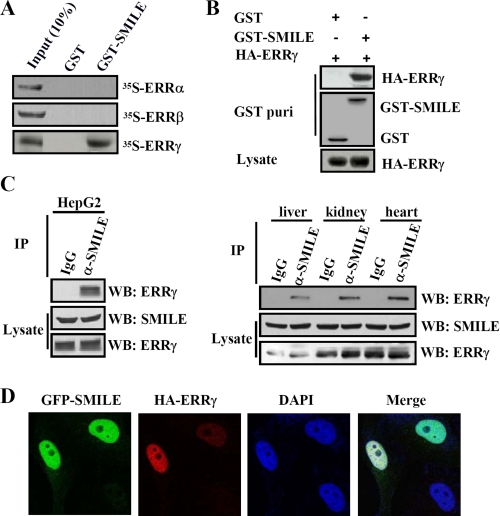

FIGURE 1.

Interaction and colocalization of SMILE with ERRγ. A, in vitro GST pulldown assays. 35S-Radiolabeled ERRα, ERRβ, or ERRγ proteins were incubated with GST or GST-SMILE fusion proteins. The input lane represents 10% of the total volume of in vitro-translated proteins used for binding assay. Protein interactions were detected via autoradiography. B, in vivo interaction between exogenous ERRγ and SMILE. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with pSG5-HA-ERRγ and pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE) or pEBG alone (GST). Protein interactions were examined via in vivo GST pulldown. The top and middle panels (GST puri) show GST beads-precipitated HA-ERRγ and GST fusion proteins, respectively. The bottom panel shows the protein expression levels of HA-ERRγ in cell lysates. C, in vivo interaction of endogenous ERRγ and SMILE. Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed using cell extract from HepG2 cells, mouse liver, kidney, and heart tissues with anti-SMILE antibody. Endogenous SMILE was immunoprecipitated (IP) with ERRγ (upper panels). The proteins in the cell lysates (middle and lower panels) were analyzed with Western blot (WB) analysis using indicated antibodies. D, colocalizations of SMILE with ERRγ. HeLa cells were transfected with 0.1 μg of expression vectors encoding GFP-SMILE and HA-ERRγ. HA fusion proteins were detected with dye Alexa 594-conjugated anti-HA monoclonal antibody. The cell images were captured under ×400 magnifications. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

To investigate whether SMILE and ERRγ are colocalized to the same subcellular compartments, confocal microscopic studies were carried out. HeLa cells were cotransfected with the mammalian expression plasmids pEGFP-SMILE and pSG5-HA-ERRγ, stained with dye Alexa 594-conjugated anti-HA antibody and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and analyzed via confocal microscopy. As shown in Fig. 1D, GFP-SMILE was predominantly localized within the nucleus and was also weakly detected in the cytoplasm, which was consistent with our previous study (16, 20). ERRγ was also observed mainly in the nucleus. The merged images indicated that SMILE and ERRγ were colocalized to the nucleus (Fig. 1D). Collectively, these data demonstrate that SMILE interacts and colocalizes with nuclear receptor ERRγ in vivo.

SMILE Inhibits Nuclear Receptor ERRγ Transactivation

We have previously reported that wild-type (WT) SMILE gene generates two isoforms through alternative translation, SMILE long form (SMILE-L) and SMILE short form (SMILE-S), which can be produced by the mutants SMILE-83Leu and SMILE-1Phe, respectively (16, 20). To examine whether these isoforms can regulate ERRγ-mediated transcriptional activity, transient transfection experiments were performed in 293T and HepG2 cells. Overexpressed wild-type SMILE inhibited ERRγ transactivation in a dose-dependent manner in both cells (Fig. 2, A and B). Furthermore, overexpression of SMILE-L or SMILE-S through the aforementioned SMILE mutants exerted similar repressive effects on ERRγ (Fig. 2, A and B). Western blot analysis showed that the protein expression of FLAG-ERRγ was not significantly changed by the overexpression of wild-type SMILE, SMILE-L, or SMILE-S alone (Fig. 2E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that both SMILE isoforms can negatively regulate ERRγ transactivation. Because SMILE-L and SMILE-S show similar effects on ERRγ, and SMILE-L is the major isoform in tested cell lines and tissues (16), we have focused on wild-type SMILE-generated SMILE-L (SMILE) for further investigations.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of overexpression and knockdown of SMILE on ERRγ transactivation. Reporter assays (A–D) were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A and B, effect of SMILE on ERRγ-mediated transcriptional activity. 293T and HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 0.3 μg of pcDNA3-FLAG-ERRγ, and 0.1 μg of sft4-Luc reporter vectors, together with indicated amounts of plasmids expressing WT SMILE, SMILE-L (SMILE-83Leu), and SMILE-S (SMILE-1Phe). C and D, siSMILE increases ERRγ transactivation. 293T and HepG2 cells were transfected with pSUPER (control (con)), or pSUPER siSMILE-I (siSM#1), or pSUPER siSMILE-II (siSM#2), or pSUPER siSHP (siSHP). After 24 h, the cells were cotransfected with expression vector for FLAG-ERRγ and sft4-Luc reporter vectors. The luciferase activity was measured 48 h after the second transfection. The means ± S.D. (n = 3) of a representative experiment are shown. **, p < 0.01, using Student's t test. E, effects of overexpressed SMILE on the protein levels of FLAG-ERRγ. 293T cells were cotransfected with various plasmids as indicated. The proteins of FLAG-ERRγ, SMILE, and tubulin were detected by respective antibodies though Western blot analysis. F, effect of siRNAs for SMILE or SHP on the expression of SMILE and SHP. 293T and HepG2 cells were transfected with pSUPER siSMILE-I (siSM#1), siSMILE-II (siSM#2), siSHP or pSUPER (Con), and after 72 h the total RNA was isolated. The mRNA levels of SHP and SMILE were measured via RT-PCR analysis, with β-actin shown as a control. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

To examine whether endogenous SMILE is involved in regulating ERRγ, ERRγ-mediated transcriptional activities were evaluated after knocking down SMILE gene expression through siRNA in 293T and HepG2 cells. As shown in Fig. 2F, siSMILE-II (siSM-II) efficiently silenced the mRNA expression of SMILE, whereas siSMILE-I (siSM-I) did not show any significant effect. As expected, loss of SMILE in 293T and HepG2 cells resulted in a 60–90% increase in ERRγ-mediated transcription of the reporter gene (Fig. 2, C and D). This effect is similar to that shown with siSHP, which knock down the gene expression of SHP (Fig. 2, D and F), a reported corepressor of ERRγ (9). These results indicate that endogenous SMILE can repress ERRγ transactivation.

Interaction Domain Mapping of SMILE with ERRγ

Because the AF2 domain of ERRγ has been reported to be involved in its interactions with corepressor DAX-1 and SHP (9, 10), we tested whether it could also mediate SMILE-ERRγ association via in vitro GST pulldown assays using the ERRγ AF2 domain deletion construct (Fig. 3A). As expected, SMILE could not interact with ERRγΔAF2, indicating that the AF2 domain of ERRγ is essential for the interaction with SMILE (Fig. 3B). To identify the SMILE domains required for ERRγ interaction, we performed in vivo GST pulldown experiments using a series of previously described (20) mammalian GST-tagged SMILE mutants (Fig. 3C). We observed that the mutant GST-SMILE-N2 (1–202 amino acids) and GST-SMILE showed significant association with ERRγ, whereas the mutants GST-SMILE-N1 (1–112 amino acids), GST-SMILE-Δ202 (203–354 amino acids), and GST-SMILE-Δ268 (269–354 amino acids) did not (Fig. 3D, upper panel). Moreover, all the GST SMILE fusions and ERRγ proteins used in the assays were expressed at comparable levels (Fig. 3D, middle and lower panels), indicating that the differences in the interactions between the SMILE mutants and ERRγ are not due to the differences in protein expression levels. Overall, these results demonstrate that ERRγ interacts with the region spanning residues 113–202 of SMILE.

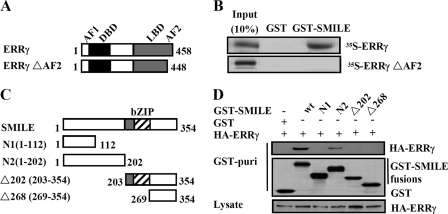

FIGURE 3.

Interaction domains of ERRγ and SMILE. A, schematic representation of the structures of ERRγ mutants. AF1, activation function-1 domain; DBD, DNA binding domain. The numbers in the figure indicate the amino acid (aa) residues. B, SMILE interacts with the AF2 domain of ERRγ. 35S-Radiolabeled ERRγ or ERRγΔAF2 proteins were incubated with GST or GST-SMILE fusion proteins. Protein interactions were detected via autoradiography. C, schematic representation of the structures of SMILE mutants. The numbers in the figure indicate the amino acid residues. D, in vivo interaction assays between ERRγ and SMILE mutants. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with expression vectors for HA-ERRγ and pEBG alone (GST) or pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE) fusions as indicated. Protein interactions were examined via in vivo GST pulldown. The top and middle panels (GST puri) show GST bead-precipitated HA-ERRγ and GST fusions, respectively. The bottom panel shows the protein expression levels of HA-ERRγ in cell lysates. wt, wild-type. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results.

SMILE Competes with Coactivators PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and GRIP1 for Binding to ERRγ

Because SMILE interacts with ERRγ AF2 domain, which is also the binding surface of coactivators PGC-1α, PGC-1β (35), and GRIP1 (8), we postulated that coactivator competition might be involved in the repression of SMILE on ERRγ. To test this hypothesis, expression vectors for PGC-1α, SMILE, and ERRγ were introduced into HepG2 cells along with sft4-Luc reporter as indicated in Fig. 4A. As expected, PGC-1α coexpression further stimulated ERRγ transactivation, and overexpression of SMILE repressed this induction in a dose-dependent manner. In a reciprocal experiment, overexpression of PGC-1α released the inhibitory effect of SMILE on ERRγ dose-dependently (Fig. 4A, upper panel). These results indicate that SMILE and PGC-1α may compete for binding to the AF2 pocket of ERRγ in cells. To confirm the direct competition between SMILE and PGC-1α, we performed in vitro competition binding assays, using in vitro translated PGC-1α and ERRγ with GST-fused SMILE. Specifically, SMILE interacted with 35S-labeled ERRγ, and PGC-1α inhibited the interaction of SMILE with ERRγ dose-dependently (lower panel in Fig. 4A). Interestingly, quite similar results were obtained when coactivators PGC-1β (Fig. 4B) and GRIP1 (Fig. 4C) were used. Taken together, these observations indicate that competing with coactivators PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and GRIP1 for binding to ERRγ may be involved in the repression of SMILE on ERRγ.

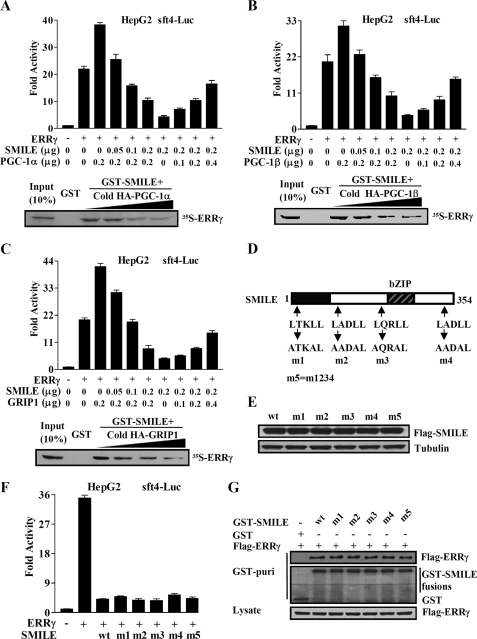

FIGURE 4.

Competition between SMILE and coactivators. Reporter assays in A–C (upper panels) were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The means ± S.D. (n = 3) of a representative experiment are shown. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 0.1 μg of sft4-Luc reporter plasmids, together with the indicated expression vectors for FLAG-ERRγ (0.2 μg), FLAG-SMILE, HA-PGC-1α, HA-PGC-1β, and HA-GRIP1. A–C, lower panels, in vitro competition of SMILE with PGC-1α, HA-PGC-1β, or HA-GRIP1. 35S-Radiolabeled ERRγ were incubated with the indicated GST or GST-SMILE fusion proteins together with increasing amounts of unlabeled in vitro-translated HA-PGC-1α, HA-PGC-1β, or HA-GRIP1 (0, 3, 6, or 12 μl) proteins. The protein interactions were detected via autoradiography. D, schematic representation of SMILE and LXXLL motif mutants of SMILE. Upper arrows indicate the locations of four LXXLL motifs in SMILE and lower arrows indicate the mutation of LXXLL motifs to AXXAL. m1, SMILE-m1 (1st LXXLL mutated to AXXAL); m2, SMILE-m2 (2nd LXXLL mutated to AXXAL); m3, SMILE-m3 (3rd LXXLL mutated to AXXAL); m4, SMILE-m4 (4th LXXLL mutated to AXXAL); m5, SMILE-m5 (all of the four LXXLL mutated to AXXAL). E, Western blot analysis using specific antibodies for SMILE and tubulin, with whole-cell extracts from HepG2 cells transfected with expression vectors encoding wild-type (wt) FLAG-SMILE or FLAG-SMILE-m1, -m2, -m3, -m4, and -m5. F, effects of SMILE LXXLL mutants on ERRγ-mediated transcriptional activity. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with reporter vector sft4-Luc, together with indicated expression vector for ERRγ, wild-type (wt) FLAG-SMILE or FLAG-SMILE LXXLL mutants. Luciferase activity was measured after 48 h of transfection. The means ± S.D. (n = 3) of a representative experiment are shown. G, in vivo interactions of SMILE LXXLL mutants with ERRγ. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with expression vectors for FLAG-ERRγ and wild-type pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE), or indicated GST-SMILE mutants, or pEBG alone (GST). Protein interactions were examined via in vivo GST pulldown. The top and middle panels (GST puri) show GST bead-precipitated FLAG-ERRγ and GST fusions, respectively. The bottom panel shows the protein expression levels of FLAG-ERRγ in cell lysates. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results.

LXXLL Motifs in SMILE Are Not Involved in the Inhibition of ERRγ Transactivity

LXXLL motif has been identified in numerous proteins that interact with the AF2 domain of the NR LBD regions (35). Many studies have shown that the motif plays an important role in the regulation of nuclear receptor signaling by coregulators, such as the p160 family of coactivators (SRC-1, -2, and -3), CBP/p300, PGC-1α, corepressors RIP140 (receptor-interacting protein-140), and SHP (36–38). Therefore we wondered whether the LXXLL motifs in SMILE are crucial for the repression of SMILE on ERRγ. To address this issue, transient transfection and reporter assays were performed using previously described (20) five SMILE LXXLL motif mutants (Fig. 4D). Surprisingly, all these mutants inhibited ERRγ transactivation to the level comparable with that observed with WT SMILE (Fig. 4F), although expression levels of all the SMILE mutants used were similar to that of WT SMILE (Fig. 4E). Moreover, the results from in vivo GST pulldown assays showed that the interactions of WT SMILE and the LXXLL motif mutants with ERRγ are comparable (Fig. 4G). Collectively, these observations indicate that all the LXXLL motifs in SMILE are not essential for SMILE to negatively regulate ERRγ, and the LXXLL motifs may not be involved in the interaction of SMILE with ERRγ.

SMILE Recruits SIRT1 to Inhibit ERRγ Transactivation

Previously we have reported that the classical HDACs are involved in the SMILE repression of GR and HNF4α (20). To examine whether those HDACs take part in the inhibitory effect of SMILE on ERRγ as well, we used inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) to block classical HDAC activity in reporter assays. In agreement with our previous report (20), TSA treatment released SMILE repression on HNF4α in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5A). By contrast, SMILE repression of ERRγ was unaltered by the TSA treatment (Fig. 5B).

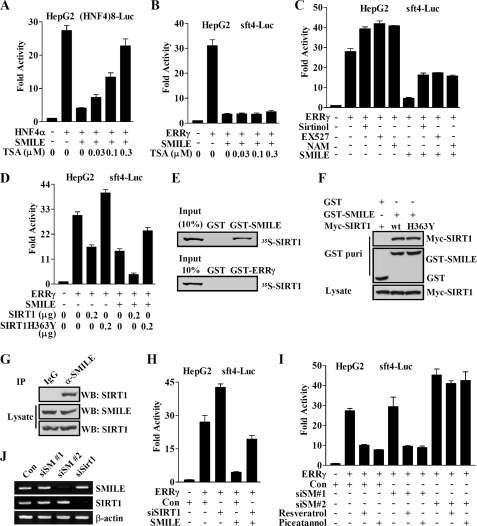

FIGURE 5.

Involvement of SIRT1 in SMILE repression of ERRγ. Reporter assays in A–D, H, and I were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The means ± S.D. (n = 3) of a representative experiment are shown. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with 0.1 μg of indicated reporter plasmids, (HNF4)8-Luc (A), or sft4-Luc (B–D) and 0.1 μg of pcDNA3-HA-HNF4α (A) or pcDNA3-FLAG-ERRγ (B–D), together with or without pcDNA3-FLAG-SMILE (0.2 μg in A–C, and 0.1 μg in D), and indicated doses of pcDNA3-Myc-SIRT1 or -SIRT1H363Y. 36 h after transfection, the cells in A–C were left untreated or treated with HDAC inhibitor TSA or SIRT1 inhibitors sirtinol (20 μm), EX527 (10 μm), or nicotinamide (NAM, 20 mm) for 12 h prior to the measurement of luciferase activity. E, in vitro interaction of SMILE and SIRT1. 35S-Radiolabeled SIRT1 protein was incubated with GST or GST-SMILE or GST-ERRγ fusion proteins. Protein interactions were detected via autoradiography. F, in vivo interaction of exogenous SIRT1 and SMILE. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with wild-type pcDNA3-myc-SIRT1 or pcDNA3-myc-SIRT1H363Y and pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE) or pEBG alone (GST). Protein interactions were examined via in vivo GST pulldown. The top and middle panels (GST puri) show GST bead-precipitated Myc-SIRT1 and GST fusions, respectively. The bottom panel shows the protein expression levels of Myc-SIRT1 in cell lysates. G, in vivo interaction of endogenous SIRT1 and SMILE. Coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed with cell extract from HepG2 cells using anti-SMILE antibody. Endogenous SMILE was immunoprecipitated with SIRT1 (upper panel). The proteins in the cell lysates (middle and lower panels) were analyzed by Western blot (WB) analysis using indicated antibodies. H and I, HepG2 cells were transfected with pSUPER (control (Con)) or pSUPER siSMILE-I (siSM#1), or pSUPER siSMILE-II (siSM#2), or pSUPER siSIRT1 (siSIRT1). After 24 h, the cells were cotransfected with expression vector for FLAG-ERRγ and sft4-Luc reporter vectors. 36 h after the second transfection, the cells were treated with or without indicated SIRT1 activators Resveratrol (100 nm) or piceatannol (20 μm) for 12 h prior to the measurement of luciferase activity. J, effect of siSMILE and siSIRT1 on the expression of SMILE and SIRT1. HepG2 cells were transfected with pSUPER siSMILE-I (siSM#1), siSMILE-II (siSM#2), siSHP or pSUPER (Con), and after 72 h the total RNA was isolated. The mRNA levels of SHP and SMILE were measured via RT-PCR analysis with β-actin shown as a control. The data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Next we investigated whether the inhibition of SMILE on ERRγ is sensitive to SIRT1-specific pharmacological inhibitors, such as EX527 (39), sirtinol, and nicotinamide (40). Interestingly, all three SIRT1 inhibitors further stimulated ERRγ-mediated sft4-Luc reporter activity and released the repression of SMILE on ERRγ transactivation significantly (Fig. 5C), indicating that the catalytic activity of SIRT1 is necessary for the repression of ERRγ by SMILE. To further confirm whether the deacetylase activity of SIRT1 is required for SMILE repression, we compared the effect of wild-type SIRT1 and a reported deacetylase-defective SIRT1 (H363Y) mutant (41) on SMILE repression. As shown in Fig. 5D, overexpression of wild-type SIRT1 or SMILE alone inhibited ERRγ transactivation by ∼50%, and the combination of SIRT1 and SMILE repressed the ERRγ activity by ∼86%. However, the dominant negative SIRT1 mutant SIRT1H363Y increased ERRγ transactivation by about 34% and released the repression of ERRγ by SMILE from 50 to 23%. These data suggest that SIRT1 deacetylase activity is needed for the repression of SMILE on ERRγ.

To examine whether ERRγ and SMILE directly interact with SIRT1, in vitro GST pulldown experiments were carried out. As shown in Fig. 5E, in vitro-translated 35S-SIRT bound to GST-SMILE but not GST-ERRγ. To further investigate whether SMILE specifically interacts with SIRT1, Myc-SIRT1, Myc-SIRT1H363Y, FLAG-SIRT6, or FLAG-SIRT7 expression vectors were introduced into HepG2 cells along with pEBG(GST) or pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE), and in vivo GST pulldown assays were performed. Myc-SIRT1 and Myc-SIRT1H363Y were detected in the coprecipitate only when coexpressed with the GST-SMILE but not with GST alone (Fig. 5F, top panel). The protein expression levels of GST, GST-SMILE, Myc-SIRT1, and Myc-SIRT1H363Y were confirmed via Western blot analysis (Fig. 5F, middle and bottom panels). By contrast, FLAG-SIRT6 and FLAG-SIRT7 were not detected in the coprecipitate (supplemental Fig. 1B). These results demonstrate that exogenous SMILE specifically interacts with SIRT1 in mammalian cells, and the mutation of H363Y does not affect the interaction of SIRT with SMILE. To further validate the association of endogenous SMILE and SIRT1, CoIP assays were carried out. As shown in Fig. 5G, endogenous SIRT1 proteins were observed to be coprecipitated with SMILE. Taken together, these results indicate that SMILE inhibits ERRγ transactivation through SMILE-mediated SIRT1 recruitment.

To further assess whether the recruitment of SIRT1 by SMILE alters ERRγ and SMILE acetylation status, expression vectors for FLAG-FOXO1, FLAG-ERRγ, or FLAG-SMILE, together with Myc-SIRT1 or Myc-SIRT1H363Y, were cotransfected into HepG2 cells. Subsequently, the acetylation/deacetylation levels of FOXO1, ERRγ, and SMILE were examined. As expected, overexpression of wild-type SIRT1 but not the catalytically inactive mutant SIRT1H363Y deacetylated FOXO1 (supplemental Fig. 2A), a well known target of SIRT1 (24), and the acetylation of FOXO1 was blocked by treatment of SIRT1 inhibitor EX527. By contrast, no significant acetylation/deacetylation signal was observed for ERRγ and SMILE (supplemental Fig. 2, B and C), indicating that the phenomenon of acetylation/deacetylation may not occur in either SMILE or ERRγ protein.

To further determine the importance of SIRT1 recruitment in SMILE repression on ERRγ, reporter assay experiments were performed after knocking down SIRT1 gene expression using siRNA in HepG2 cells. As shown in Fig. 5J, siSIRT1 efficiently knocked down the mRNA expression of SIRT1. The silencing of SIRT1 significantly increased ERRγ transactivation and released SMILE-mediated repression of ERRγ by ∼60%, indicating SIRT1 is required for the full inhibition of SMILE on ERRγ (Fig. 5H). In a parallel experiment, we investigated the effect of SIRT1 activators Resveratrol and piceatannol on ERRγ transactivation before and after siRNA-mediated gene silencing of SMILE. Of great interest, Resveratrol and piceatannol treatment significantly inhibited ERRγ-mediated transcriptional activity. However, those SIRT1 activators failed to repress ERRγ after shutdown of SMILE gene expression by siSMILE-II (siSM-2) (Fig. 5, I and J). Taken together, these observations suggest that the activation of SIRT1 by chemicals resulted in the inhibition of ERRγ transactivation, and this issue depends on the expression of SMILE.

SMILE Is Required for the ERRγ Inverse Agonist GSK5182-mediated Transrepression

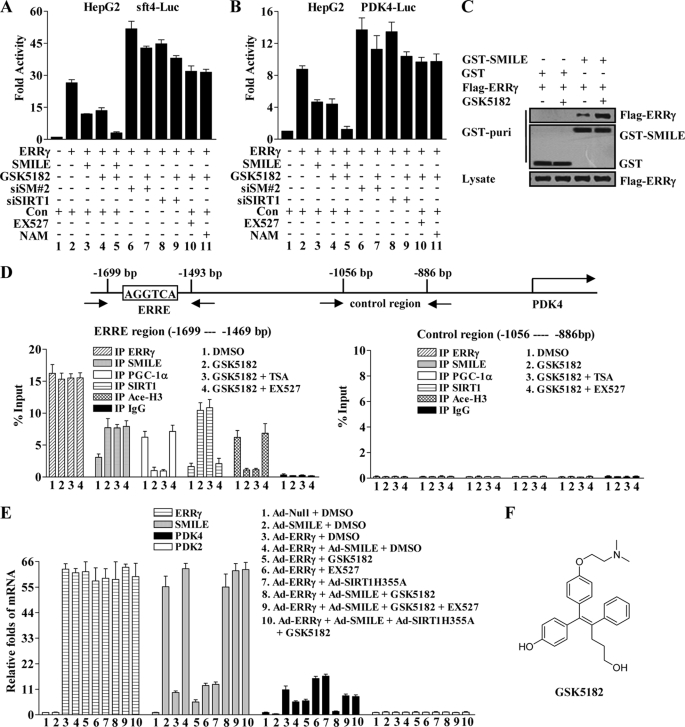

It has been reported that GSK5182 (Fig. 6F), a synthetic 4-hydroxytamoxifen derivative, acts as an ERRγ inverse agonist through binding to the ERRγ LBD region (14). Because SMILE binds to the AF2 domain of the ERRγ LBD region, we hypothesized that ERRγ inverse agonist might recruit SMILE to repress ERRγ transactivation. Therefore, we tested whether SMILE and GSK5182 could cooperatively inhibit ERRγ transactivation. As expected, GSK5182 treatment and overexpression of SMILE alone inhibited ERRγ-mediated sft4-Luc reporter activity by ∼50–55% (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 3 and 4 with lane 2). Moreover, SMILE enhanced the transrepression of ERRγ by GSK5182 up to about 88%. Next, we examined whether the GSK5182-mediated repression of ERRγ depends on SMILE or SIRT1. Interestingly, knockdown of SMILE or SIRT1 gene expression decreased the transrepression of ERRγ by GSK5182 to ∼17 or 13% (Fig. 6A, compare lane 7 with lane 6 and lane 9 with lane 8), respectively. In the presence of SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 or nicotinamide, GSK5182 did not show any significant repression on ERRγ (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 10 and 11 with lane 2). Furthermore, similar results were obtained when PKD4-Luc reporter was used (Fig. 6B). Taken together, these observations indicate that ERRγ inverse agonist GSK5182 can strengthen the repressive effect of SMILE on ERRγ and the transrepression of ERRγ by GSK5182 relies on SMILE and SIRT1.

FIGURE 6.

ERRγ inverse agonist GSK5182 enhances SMILE to down-regulate ERRγ target PDK4. A and B, GSK5182 represses ERRγ transactivation in a SMILE and SIRT1-dependent manner. HepG2 cells were transfected with pSUPER siSMILE-II (siSM#2), siSIRT1, or pSUPER (Con) as indicated. 24 h after transfection, the cells were cotransfected with 0.1 μg of indicated reporter plasmids, sft4-Luc (A) or PDK4-Luc (B) and 0.2 μg of pcDNA3-FLAG-ERRγ, together with or without 0.1 μg of pcDNA3-FLAG-SMILE (A–C). 36 h after transfection, the cells were treated with chemicals (1 μm GSK5182, 10 μm EX527, or 20 mm nicotinamide (NAM)) as indicated for 12 h prior to the measurement of luciferase activity. The means ± S.D. (n = 3) of a representative experiment are shown. C, GSK5182 treatment intensifies the interaction between ERRγ and SMILE. HepG2 cells were cotransfected with pcDNA3-FLAG-ERRγ and pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE) or pEBG alone (GST), and 36 h after transfection, the cells were treated with or without 1 μm GSK5182. Cell extracts were prepared and subjected to in vivo GST pulldown assays in the absence or presence of GSK5182 as indicated. The top and middle panels (GST puri) show GST bead-precipitated FLAG-ERRγ and GST fusions, respectively. The bottom panel shows the protein expression levels of FLAG-ERRγ in the cell lysates. D, recruitment of SMILE by GSK5182 on PDK4 promoters is correlated with PGC-1α dissociation and histone 3 deacetylation in ChIP assays. HepG2 cells were treated with or without indicated chemicals (0.1% DMSO, 1 μm GSK5182, 0.3 μm TSA, and 10 μm EX527). Chromatin fragments prepared from the treated HepG2 cells were immunoprecipitated with the indicated specific antibodies. Unrelated immunoglobin G (IgG) was used as a negative control. DNA fragments covering an ERRE on human PDK4 promoter are indicated in the upper panel. The occupancy of ERRγ, SMILE, PGC1α, SIRT1, and acetylated histone H3 (Ace-H3) on the ERRγ-binding region (lower left panel) was analyzed by amplifying the corresponding regions using quantitative real time PCR. A control region on the PDK4 promoter was used to check the specific binding of those proteins (lower right panel). Data are representative of at least two independent IP and three independent PCR amplifications. Values are presented as mean ± S.D. E, relative mRNA expression levels of ERRγ, SMILE, PDK4, and PDK2 analyzed by quantitative real time PCR (standardized using β-actin). Normalized basal levels of each transcript were assigned an arbitrary value of 1.0 for comparison. HepG2 cells were infected with indicated adenovirus vector (Ad-Null, Ad-ERRγ, Ad-SMILE, and Ad-SIRT1H355A) at a concentration of 100 plaque-forming units/cell. After 36 h of infection, the cells were stimulated with or without indicated chemicals (0.1% DMSO, 1 μm GSK5182, and 10 μm EX527) for 12 h before total RNA were isolated. Data shown are representative of three independent experiments. F, structure of ERRγ inverse agonist GSK5182.

To determine whether GSK5182 affects the interaction of ERRγ and SMILE, expression vectors for FLAG-ERRγ along with pEBG(GST) or pEBG-SMILE (GST-SMILE) were cotransfected into HepG2 cells, and then in vivo GST pulldown assays were performed with the whole-cell extracts in the presence or absence of GSK5182. GSK5812 treatment substantially increased the binding of FLAG-ERRγ to GST-SMILE (Fig. 6C, upper panel). In addition, the protein expression levels of FLAG-ERRγ and GST-SMLE were not significantly changed by GSK5812 (Fig. 6C, middle and bottom panels).

ERRγ Inverse Agonist GSK5182 Enhances Overexpressed SMILE to Down-regulate the Expression of ERRγ Target Gene

Next, we performed ChIP assays to examine whether SMILE associates with the ERRγ on the promoter of PDK4, a known target of ERRγ (42, 43). Specific primers that flanked an ERRE AGGTCA in the PDK4 promoter were used for quantitative real time PCR analysis (Fig. 6D, upper panel). We observed that low levels of SMILE and SIRT1 and high levels of PGC-1α were associated with the PDK4 promoter in the absence of GSK5182. Treatment of GSK5182 increased the occupancy of SMILE and SIRT1 but decreased the occupancy of PGC-1α (Fig. 6D, lower left panel). However, no significant recruitment was observed in the control region of the PDK4 promoter (Fig. 6D, lower right panel). These results indicate that SMILE forms a complex with ERRγ on the PDK4 promoter, and the recruitment of SMILE can be increased by GSK5182, which leads to the dissociation of PGC-1α.

Based on the results that the repression of SMILE was sensitive to the inhibition of SIRT1 catalytic activity and SMILE interacted with SIRT1 (Fig. 5, C–G), we speculated that the recruitment of SMILE to PDK4 promoter might lead to promoter-complexed histone deacetylation. To address this issue, ChIP assays were performed with antibodies against acetylated lysine 9 of histone H3 (Ace-H3). As shown in Fig. 6D, in the absence of GSK5182, high acetylation level of the histone H3 on the ERRγ binding region of PDK4 promoter was observed (lower left panel). However, the acetylation level significantly decreased by the treatment of GSK5182 (Fig. 6D, left in lower panel), which coincides with the increased SMILE and SIRT1 association. Interestingly, the decrease in the acetylation level of histone H3 was recovered by SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 but not by HDAC inhibitor (TSA) treatment (Fig. 6D, lower left panel). Taken together, these results indicate that the increased recruitment of SMILE on PDK4 promoters is associated with increased chromatin histone deacetylation.

Because aforementioned data suggest that GSK5182 strengthens SMILE to repress ERRγ-mediated transactivation and to form a complex with ERRγ on the ERRγ target PDK4 promoter, we next examined the effect of GSK5182 and SMILE on PDK4 gene expression. As expected, overexpression of ERRγ through adenovirus increased PDK4 mRNA levels by ∼10.5-fold (Fig. 6E, compare lane 3 with lane 1), and overexpressed SMILE and GSK5182 alone conspicuously repressed Ad-ERRγ-induced as well as the basal mRNA levels of PDK4 in HepG2 cells (Fig. 6E, compare lanes 4 and 5 with lane 3 and lane 2 with lane 1). Interestingly, GSK5182 enhanced the inhibitory effect of SMILE on PKD4 gene expression (Fig. 6E, compare lane 8 with lane 4 and 5). Moreover, the treatment of SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 recovered SMILE- and GSK5182-repressed mRNA levels of PDK4 by ∼80%, and overexpression of a deacetylase-defective SIRT1(H355A) mutant (34) via adenovirus showed a similar effect as EX527 (Fig. 6E, compare lane 9 and 10 with lane 8). In addition, those treatments did not significantly affect the mRNA levels of PDK2, which is a non-ERRγ target (6). Collectively, these observations demonstrate that ERRγ inverse agonist GSK5182 and SMILE function cooperatively to reduce ERRγ-mediated PDK4 gene expression, and this repression depends on SIRT1 activity.

Autoregulatory Loop Controlling SMILE Gene Expression by ERRγ

Interestingly, overexpression of ERRγ through adenovirus vector increased SMILE mRNA levels (Fig. 6E, compare lane 3 with lane 1), indicating that SMILE might be a target of ERRγ. Indeed, adenovirus-mediated overexpression of ERRγ up-regulated both mRNA and protein levels of SMILE dose-dependently (Fig. 7A). We next examined whether ERR family members could regulate the human SMILE promoter. To address this issue, we first identified the transcription start site in the SMILE gene through primer extension analysis. The apparent start site of transcription identified by these studies locates 224 nucleotides upstream from the translation start codon ATG (supplemental Fig. 4). Next, we cloned an ∼1-kb fragment of the human SMILE promoter sequences into a luciferase reporter construct and performed transient transfection experiments in HepG2 cells. As shown in Fig. 7B, overexpression of ERRγ significantly activated SMILE promoter activity in a dose-dependent manner, whereas ERRα and ERRβ did not show any significant effect. Our aforementioned data demonstrated that SMILE inhibits ERRγ transactivation via coactivator competition; therefore, we next investigated whether SMILE could repress ERRγ on its own promoter. As expected, overexpression of SMILE repressed ERRγ-mediated and PGC-1α-enhanced SMILE promoter transcriptional activity (Fig. 7C).

Previously we have shown that ERRγ recognizes the sequence T(N)AAGGTCA or AGGTCA (half-sites) or TCAAGGTGG (9, 10). Sequence analysis of SMILE promoter showed that there are two putative ERRγ-response elements (ERRE1 and ERRE2) in the SMILE promoter (Fig. 7D). To further examine whether these elements were required for ERRγ-induced SMILE promoter transcriptional activity, a series of mutants of the SMILE promoter were generated (Fig. 7D). As shown in Fig. 7E, deletion of the promoter sequence up to nucleotide −879 decreased ERRγ-dependent activation of the SMILE promoter by ∼95%. Moreover, mutation of ERRE2 (mtERRE2-Luc) decreased ERRγ-stimulated SMILE promoter activity by ∼95%, whereas mutation of ERRE1 (mtERRE1-Luc) had no significant effect. Taken together, these results indicate that ERRE2 is essential for ERRγ-mediated transactivation of the SMILE promoter. To further examine whether ERRγ directly binds to the ERRE in the SMILE promoter, ChIP assays were carried out using specific primers to amplify the region spanning the ERRE1 and ERRE2. Expression vectors encoding HA fusion protein of ERRγ (HA-ERRγ) or HA alone were transfected into HepG2 cells. As shown in Fig. 7F, a 262-bp fragment (corresponding to ERRE1 and ERRE2) was amplified from cells that expressed HA-ERRγ but not HA alone. In addition, no significant ERRγ binding was observed in the control region of SMILE promoter. These results demonstrate that ERRγ is specifically associated with the SMILE promoter in vivo.

Overall, these results suggest that ERRγ regulates SMILE gene expression via directly binding to the ERRE in the SMILE promoter, and SMILE in turn inhibits ERRγ transactivation on the SMILE promoter, indicating the existence of an autoregulatory loop.

DISCUSSION

The bZIP protein SMILE has been reported to regulate the transactivation of several transcription factors, including ERs, host-cell factor, CREB3, and ATF4 (6, 17–19). Recently, we have reported that SMILE acts as a novel corepressor of nuclear receptors GR, CAR, and HNF4α (20). In this study, we identified ERRγ as a novel target of SMILE repression. SMILE directly interacts with ERRγ in vitro and in vivo. SMILE inhibits ERRγ transactivation through coactivator competition and recruitment of SIRT1, a class III HDAC. Moreover, knockdown of the endogenous SMILE and SIRT1 gene expression increases ERRγ-mediated transcriptional activity. In addition, the ERRγ-specific inverse agonist GSK5182 increased SMILE-ERRγ association and enhanced the repression of SMILE on ERRγ-mediated transactivation and the PDK4 mRNA level. Given the coexpressions of SMILE and ERRγ in the liver, heart, skeletal muscle, kidney, and brain (16, 43, 44), these observations indicate that the corepressor SMILE may play an important role in ERRγ signaling.

Our previous work has shown that SMILE interacted with ERRα, ERRβ, and ERRγ in yeast two-hybrid assays (20). However, in this study, we observed that SMILE specifically interacts with ERRγ in mammalian cells, as demonstrated through in vivo GST pulldown and CoIP assays (Fig. 1). This discrepancy of interaction pattern could be due to the difference between yeast and mammalian cell system. Our previous report has shown that the region spanning residues 113–202 of SMILE interacts with the LBD/AF2 domain of GR, CAR, and HNF4α (20). Similarly, we have observed that SMILE uses the same region for binding to AF2 domain of ERRγ (Fig. 3). It is well known that the AF2 domain of NRs is usually involved in its binding to coactivators (1) and that ERRγ binds to coactivators PGC-1α, PGC- 1β, and GRIP1 though its AF2 domain (34, 35). Therefore, it is not surprising to find that SMILE competes with PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and GRIP1 for binding to ERRγ (Fig. 4, A–C). As numerous other coactivators and corepressors are known to interact with ERRγ (3), whether SMILE may also affect the interactions of ERRγ with those coregulators still needs to be determined.

It has been well established that LXXLL is a common motif found in NR coregulators to interact with the LBD/AF2 domain of NRs (35, 36). However, the LXXLL motifs in SMILE are apparently not important for the SMILE-ERRγ association and the repression of ERRγ by SMILE (Fig. 4, B–E). This LXXLL-independent interaction between coregulator and LBD/AF2 domain of NRs has also been demonstrated in our previous report (20), in the association between ERα and proline-rich nuclear receptor coregulatory protein, and in the case of corepressor RIP140 (45, 46). In addition, the bZIP region is known to be essential for the dimerization and functions of bZIP proteins (47). However, we found that the bZIP region of SMILE is required for the homodimerization but is not essential for the repressive effect of SMILE on ERRγ (supplemental Fig. 3), which is consistent with our previous observation (20).

Competition with coactivators is a common repression mechanism among certain corepressors, including SHP (9), DAX-1 (10), RIP140 (11), and the corepressor silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptors (48). Our study indicates that SMILE also competes with coactivators PGC-1α, PGC-1β, and GRIP1 to repress ERRγ transactivation (Fig. 4, A–C). However, overexpression of these coactivators only partially releases the repression by SMILE (Fig. 4, A–C), indicating that coactivator competition is not completely responsible for the transrepression. Of interest, coactivator competition was also involved in the repression of SMILE on GR, CAR, and HNF4α (20). In contrast with our previous observation that certain class I and II HDACs are required for the full repression of SMILE on GR and HNF4α (20), the class III HDAC SIRT1 took the place of classical HDACs to contribute to the inhibition of SMILE on ERRγ, as demonstrated by the findings that the repression was significantly released by SIRT1 inhibitors, and siSIRT1, but not by the specific classical HDACs inhibitor TSA (Fig. 5, B, C, and H).

SIRT1 has been reported to regulate a large number of transcription factors through direct deacetylation of target proteins, including FOXO transcriptional factors, PPARα, PPARγ, PGC-1α, liver X receptor α, and liver X receptor β (24–29). In contrast, the regulation of SIRT1 on ERRγ is not through a direct interaction between SIRT1 and ERRγ but through association with SMILE (Fig. 5, E–G). Moreover, the phenomenon of acetylation/deacetylation does not occur on either SMILE or ERRγ protein (supplemental Fig. 2), indicating SIRT1 regulation of SMILE and ERRγ may not be due to direct deacetylation of these two proteins. Of note, the repression of SMILE on ERRγ activity is not only sensitive to the inhibition of SIRT1 catalytic activity by pharmacological inhibitors (Fig. 5C and Fig. 6, A, B, and E) but is also sensitive to the overexpression of two different deacetylase-defective mutants of SIRT1 (H363Y and H355A) (Fig. 5D and Fig. 6E), indicating that the deacetylase activity of SIRT1 is required for the repression of ERRγ by SMILE. Moreover, we have demonstrated that the recruitment of SIRT1 by SMILE on ERRγ target PDK4 promoter is correlated with the promoter-complexed histone 3 deacetylation in ChIP assays, and this deacetylation is sensitive to SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 but not to classical HDAC inhibitor TSA (Fig. 6D). These results further support the importance of SIRT1 deacetylase activity in SMILE-stimulated repression on ERRγ and implicate SIRT1 as a histone H3 deacetylase in mammalian cells. Of interest, SIRT1 has been reported to play a similar role in chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor (COUP-TF)-interacting protein 2-mediated transcriptional repression (49). However, SMILE is also a corepressor of GR, HNF4α, and CAR (20); whether SIRT1 plays a similar role in the repression of SMILE on those NRs needs to be further clarified.

In this model of transcriptional regulation by NRs, agonist-bound receptors recruit coactivators such as the PGC-1α and histone acetyltransferase complex, leading to expression of target genes. The antagonist-bound receptors bind corepressors such as N-CoR/silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid receptors and histone deacetylase complexes, leading to silencing of target genes (1). For instance, promoter-bound hydroxytamoxifen-complexed ERα is associated with NCoR-HDAC3 complexes, resulting in the suppression of ER-mediated pS2 and c-myc gene transcription (50) In line with this model, our study demonstrated that inverse agonist GSK5182-bound ERRγ recruits SMILE-SIRT1 corepressor complex to PDK4 gene promoter, resulting in the dissociation of coactivator PGC-1α and repressed gene expression of PDK4 (Fig. 6). These results shed light on a mechanism for the repression of ERRγ by GSK5182.

In the oxidation of glucose to acetyl-CoA, the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is a key enzyme catalyzing the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA (51). PDK2 and PDK4, highly expressed pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoforms in the liver, heart, and skeletal muscle, negatively regulate pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity via phosphorylation (52). It has been reported that the decrease in pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in diabetes is a consequence of increased pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase activity (51). In light of our results that SMILE and ERRγ inverse agonist GSK5182 cooperatively down-regulate ERRγ-mediated PDK gene expression in a SIRT1 activity-dependent manner (Fig. 6E), it is very likely that SMILE and SIRT1 function synergistically in the regulation of glucose oxidation. However, it should be pointed out that further investigations are required to find out the upstream signaling of SMILE. Previously, it has been reported that insulin inhibits the induction of the PDK4 gene by both ERRγ and PGC-1α (6). Whether SMILE is involved in this insulin-mediated repression awaits further exploration. Because PGC-1α, retinoic acid receptor α, and cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27 are known targets of ERRγ (4, 5, 7), it would be interesting to further examine whether SMILE represses their expression through inhibiting ERRγ. In addition, as our observations were obtained from cell culture studies, in the future, it would be necessary to investigate whether ERRγ is more functionally active in SIRT1 or SMILE knock-out mice.

Previously, we have reported that ERRγ regulates SHP and DAX-1 gene promoters (9, 10). This study indicates that the SMILE promoter is also a target of ERRγ. Although there are two potential ERREs in the human SMILE promoter, the data from mutation analysis suggest that ERRE2 is responsible for ERRγ-mediated transactivation of the SMILE promoter (Fig. 7). It has been reported that ERRs (ERRα, ERRβ, and ERRγ) bind to the same DNA-response elements (1–3); however, in this work, only ERRγ significantly activated the SMILE promoter (Fig. 7). This indicates that some other factors except DNA binding may affect the transactivation. As demonstrated in Fig. 7, ERRγ regulated the transcription of SMILE, which in turn repressed ERRγ transactivation. These results suggest the existence of an autoregulatory loop. Of great interest, similar autoregulatory loops also exist in the regulation of SHP and DAX-1 by ERRγ (9, 10). Certainly, the physiological role of ERRγ regulation of SMILE gene expression needs to be further investigated.

In summary, as depicted in Fig. 7G, we proposed that ERRγ activates the SMILE promoter, whereas SMILE in turn inhibits ERRγ. The binding of the inverse agonist GSK5182 to ERRγ recruits the corepressor SMILE-SIRT complex, which leads to the dissociation of coactivator PGC-1α and silencing of ERRγ target gene PDK4. Our observations provide new insight into understanding the repressive mechanism of SMILE, SIRT1, and ERRγ inverse agonist.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Drs. Seok-Yong Choi, Balachandar Nedumaran, and Dipanjan Chanda for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Research Laboratory Grant ROA-2005-000-10047-0 and the Korea Research Foundation Grant KRF-2006-005-J03003.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Tables 1 and 2 and Figs. S1–S4.

- ERR

- estrogen receptor-related receptor

- CAR

- constitutive androstane receptor

- GR

- glucocorticoid receptor

- HNF4α

- hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α

- ERRE

- ERR-response element

- SHP

- small heterodimer partner

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- HDAC

- histone protein deacetylase

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- RT

- reverse transcription

- qPCR

- quantitative real time PCR

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- NR

- nuclear receptor

- LBD

- ligand binding domain

- TSA

- trichostatin A

- CoIP

- coimmunoprecipitation

- WT

- wild type

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- AF2

- activation function-2 domain

- bZIP

- basic region leucine zipper domain

- CREB

- cAMP-response element-binding protein.

REFERENCES

- 1.Giguère V. (1999) Endocr. Rev. 20, 689–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pettersson K., Svensson K., Mattsson R., Carlsson B., Ohlsson R., Berkenstam A. (1996) Mech. Dev. 54, 211–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giguère V. (2008) Endocr. Rev. 29, 677–696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu S., Wang X., Ng C. F., Chen S., Chan F. L. (2007) Cancer Res. 67, 4904–4914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L., Liu J., Saha P., Huang J., Chan L., Spiegelman B., Moore D. D. (2005) Cell Metab. 2, 227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y., Ma K., Sadana P., Chowdhury F., Gaillard S., Wang F., McDonnell D. P., Unterman T. G., Elam M. B., Park E. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39897–39906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dufour C. R., Wilson B. J., Huss J. M., Kelly D. P., Alaynick W. A., Downes M., Evans R. M., Blanchette M., Giguère V. (2007) Cell Metab. 5, 345–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong H., Yang L., Stallcup M. R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 22618–22626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanyal S., Kim J. Y., Kim H. J., Takeda J., Lee Y. K., Moore D. D., Choi H. S. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1739–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park Y. Y., Ahn S. W., Kim H. J., Kim J. M., Lee I. K., Kang H., Choi H. S. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 6756–6768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Castet A., Herledan A., Bonnet S., Jalaguier S., Vanacker J. M., Cavaillès V. (2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 1035–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tremblay G. B., Bergeron D., Giguere V. (2001) Endocrinology 142, 4572–4575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coward P., Lee D., Hull M. V., Lehmann J. M. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 8880–8884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chao E. Y., Collins J. L., Gaillard S., Miller A. B., Wang L., Orband-Miller L. A., Nolte R. T., McDonnell D. P., Willson T. M., Zuercher W. J. (2006) Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 16, 821–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu R., Misra V. (2000) Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 2446–2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie Y. B., Lee O. H., Nedumaran B., Seong H. A., Lee K. M., Ha H., Lee I. K., Yun Y., Choi H. S. (2008) Biochem. J. 416, 463–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akhova O., Bainbridge M., Misra V. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 14708–14718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misra V., Rapin N., Akhova O., Bainbridge M., Korchinski P. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15257–15266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hogan M. R., Cockram G. P., Lu R. (2006) FEBS Lett. 580, 58–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie Y. B., Nedumaran B., Choi H. S. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 4100–4115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Blander G., Guarente L. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 73, 417–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo J., Nikolaev A. Y., Imai S., Chen D., Su F., Shiloh A., Guarente L., Gu W. (2001) Cell 107, 137–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajamohan S. B., Pillai V. B., Gupta M., Sundaresan N. R., BiruKov K. G., Samant S., Hottiger M. O., Gupta M. P. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 4116–4129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunet A., Sweeney L. B., Sturgill J. F., Chua K. F., Greer P. L., Lin Y., Tran H., Ross S. E., Mostoslavsky R., Cohen H. Y., Hu L. S., Cheng H. L., Jedrychowski M. P., Gygi S. P., Sinclair D. A., Alt F. W., Greenberg M. E. (2004) Science 303, 2011–2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Motta M. C., Divecha N., Lemieux M., Kamel C., Chen D., Gu W., Bultsma Y., McBurney M., Guarente L. (2004) Cell 116, 551–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purushotham A., Schug T. T., Xu Q., Surapureddi S., Guo X., Li X. (2009) Cell Metab. 9, 327–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picard F., Kurtev M., Chung N., Topark-Ngarm A., Senawong T., Machado, De Oliveira R., Leid M., McBurney M. W., Guarente L. (2004) Nature 429, 771–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nemoto S., Fergusson M. M., Finkel T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 16456–16460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X., Zhang S., Blander G., Tse J. G., Krieger M., Guarente L. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 91–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.North B. J., Marshall B. L., Borra M. T., Denu J. M., Verdin E. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kressler D., Schreiber S. N., Knutti D., Kralli A. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 13918–13925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamagata K., Daitoku H., Shimamoto Y., Matsuzaki H., Hirota K., Ishida J., Fukamizu A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23158–23165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kwon H. S., Huang B., Unterman T. G., Harris R. A. (2004) Diabetes 53, 899–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han M. K., Song E. K., Guo Y., Ou X., Mantel C., Broxmeyer H. E. (2008) Cell Stem Cell 2, 241–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hentschke M., Süsens U., Borgmeyer U. (2002) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 299, 872–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Savkur R. S., Burris T. P. (2004) J. Pept. Res. 63, 207–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Heery D. M., Hoare S., Hussain S., Parker M. G., Sheppard H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 6695–6702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chanda D., Park J. H., Choi H. S. (2008) Endocr. J. 55, 253–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solomon J. M., Pasupuleti R., Xu L., McDonagh T., Curtis R., DiStefano P. S., Huber L. J. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 28–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pfister J. A., Ma C., Morrison B. E., D'Mello S. R. (2008) PLoS ONE 3, e4090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dai Y., Ngo D., Forman L. W., Qin D. C., Jacob J., Faller D. V. (2007) Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1807–1821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J., Fang F., Huang Z., Wang Y., Wong C. (2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 643–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z., Teng C. T. (2007) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 264, 128–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang X., Downes M., Yu R. T., Bookout A. L., He W., Straume M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Evans R. M. (2006) Cell 126, 801–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou D., Ye J. J., Li Y., Lui K., Chen S. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 5974–5986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee C. H., Wei L. N. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 31320–31326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Deppmann C. D., Alvania R. S., Taparowsky E. J. (2006) Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 1480–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ruse M. D., Jr., Privalsky M. L., Sladek F. M. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 1626–1638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Senawong T., Peterson V. J., Avram D., Shepherd D. M., Frye R. A., Minucci S., Leid M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43041–43050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X. F., Bagchi M. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15050–15058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harris R. A., Bowker-Kinley M. M., Huang B., Wu P. (2002) Adv. Enzyme Regul. 42, 249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwon H. S., Harris R. A. (2004) Adv. Enzyme Regul. 44, 109–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.