Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and related growth factors are essential regulators of embryogenesis and tissue homeostasis. The signaling pathways mediated by their receptors and Smad proteins are precisely modulated by various means. Xenopus BAMBI (bone morphogenic protein (BMP) and activin membrane-bound inhibitor) has been shown to function as a general negative regulator of TGF-β/BMP/activin signaling. Here, we provide evidence that human BAMBI (hBAMBI), like its Xenopus homolog, inhibits TGF-β- and BMP-mediated transcriptional responses as well as TGF-β-induced R-Smad phosphorylation and cell growth arrest, whereas knockdown of endogenous BAMBI enhances the TGF-β-induced reporter expression. Mechanistically, in addition to interfering with the complex formation between the type I and type II receptors, hBAMBI cooperates with Smad7 to inhibit TGF-β signaling. hBAMBI forms a ternary complex with Smad7 and the TGF-β type I receptor ALK5/TβRI and inhibits the interaction between ALK5/TβRI and Smad3, thus impairing Smad3 activation. These findings provide a novel insight to understand the molecular mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of BAMBI on TGF-β signaling.

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)3 and related growth factors regulate various aspects of cellular events, including cell growth, differentiation, migration, and death and play pivotal roles in many physiological and pathological processes (1–7). TGF-β signaling is initiated by binding of ligands to two types of transmembrane receptors, both of which possess Ser/Thr kinase activity in their intracellular domains. Ligand binding induces the heterocomplex formation between the type I (ALK5/TβRI) and the type II (TβRII) receptors and thus the TβRII-mediated activation of ALK5. Then the activated ALK5 recruits and phosphorylates the downstream signal mediators Smad2 or Smad3 proteins, which subsequently associates with Smad4, accumulates in the nucleus, and modulates target gene expression (8–15). TGF-β signaling is tightly regulated temporally and spatially through multiple mechanisms at different levels: from the extracellular environment, the plasma membrane, and the cytoplasm to the nucleus. The regulation can take place in either positive or negative manners. Deregulation of TGF-β signaling might be linked to pathogenesis of various clinical disorders such as tumors, vascular diseases, and tissue fibrosis (4, 5, 16–18). Inhibitory Smads, including Smad7 and Smad6, are key regulators of TGF-β family signaling through a negative feedback circuit (19–21).

BAMBI (BMP and activin membrane-bound inhibitor), a 260-amino acid transmembrane glycoprotein that is evolutionally conserved in vertebrates from fish to humans, is closely related to the type I receptors of the TGF-β family in the extracellular domain but has a shorter intracellular domain that exhibits no enzymatic activity (22–24). It has been documented that Xenopus BAMBI functions as a general antagonist of TGF-β family members by acting as a pseudoreceptor to block the interaction between signaling type I and type II receptors (24). BAMBI is tightly co-expressed with BMP4 during the embryo development of zebrafish, Xenopus, bird, or mouse, and its expression is also induced by BMP4 (22, 24–27). Therefore, BAMBI is believed to act as a negative feedback regulator of BMP signaling during embryo development (24, 25), although a recent gene target study indicated that BAMBI is dispensable for mouse embryo development and postnatal survival (28). BAMBI expression is also induced by TGF-β (29, 30) and Wnt signaling (31). Our recent work showed that human BAMBI (hBAMBI) can promote Wnt signaling by enhancing the interaction of the Wnt receptor Frizzled5 and the downstream mediator Dishevelled2 (32), implicating that BAMBI might integrate different cellular signaling pathways.

Several studies have suggested that BAMBI is involved in pathogenesis of human diseases. Human BAMBI, initially named nma, is down-regulated in metastatic melanoma cell lines (33) and in a subset of high grade bladder cancer (34). Its elevated expression was suggested to attenuate the TGF-β-mediated growth arrest in colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas (31) and to induce cell growth and invasion of human gastric carcinoma cells (35). A recent study has also suggested that BAMBI is involved in Toll-like receptor 4- and lipopolysaccharide-mediated hepatic fibrosis (36).

Although BAMBI acts as a critical regulator of TGF-β/BMP signaling, how the regulation takes place is not fully understood. In this study, we demonstrated that hBAMBI, like its Xenopus homolog, inhibits TGF-β- and BMP-mediated transcriptional responses, TGF-β-induced phosphorylation of R-Smads, and cell growth arrest. In addition to its interference with receptor complex formation, we found that hBAMBI can synergize with Smad7 to inhibit TGF-β signaling by forming a ternary complex with ALK5 and Smad7 and inhibiting the interaction between ALK5 and R-Smads. These findings together suggest that the function of BAMBI is evolutionally conserved as a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture, Reagents, and Antibodies

Hep3B, Mv1Lu, and L17 were maintained in minimum essential medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, and HEK293, HEK293T NMuMG, and HeLa cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% CO2 incubator. To generate NMuMG cells stably expressing hBAMBI, the cells were transfected using Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen) and selected for stable transfects with 0.8 mg/ml G418. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to hBAMBI and human Smad7 was prepared by immunizing rabbits with a synthesized peptide (HWGMYSGHGKLEFV), corresponding to the C-terminal tail of BAMBI and with the glutathione S-transferase-fused N-terminal domain of Smad7 (amino acids 1–259), respectively. The other antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Plasmid Constructs

Human BAMBI (nma) cDNA was tagged with various tags at the C terminus and subcloned into pCMV5 or pcDNA3.1. An shRNA construct to knock down hBAMBI expression was generated by subcloning into pSuper vector of the double nucleotide sequences annealed from following oligonucleotides: forward primer, 5′-GATCCCCATCTGAGCTCAGCGCCTGCTTCAAGAGAGCAGGCGCTGAGCTCAGATTTTTTGAAA-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAATCTGAGCTCAGCGCCTGCTCTCTTGAAGCAGGCGCTGAGCTCAGATGGG-3′. shRNA construct to knock down human Smad7 was generated similarly with the following oligonucleotides: forward primer, 5′-GATCCCCGAGGCTGTGTTGCTGTGAATTCAAGAGATTCACAGCAACACAGCCTCTTTTTGGAAA-3′, and reverse primer, 5′-AGCTTTTCCAAAAAGAGGCTGTGTTGCTGTGAATCTCTTGAATTCACAGCAACACAGCCTCGGG-3′. Other constructs were described previously (32, 37). The constructs encoding the extracellular transmembrane domain (1–173 amino acids) or the transmembrane-intracellular domain (153–260 amino acids) (with the signal peptide, 1–20 amino acids) of BAMBI were subcloned in pCMV with the Myc tag at the C terminus.

Luciferase Reporter Assays

The cells were plated in 24-well dishes at 18 h prior to transfection. Transfection was performed with Lipofectamine reagent (Invitrogen). Luciferase activity was measured at 48 h after transfection by using the dual luciferase reporter assay system (Promega, Madison, WI) following the manufacturer's protocol. Reporter activity was normalized to co-transfected Renilla. The experiments were repeated in triplicate.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry experiment was performed as described previously (32).

Transfection, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunoblotting

The cells were plated in 100- or 60-mm dishes at 18 h prior to transfection. Transfections were performed by calcium phosphate precipitation or Lipofectamine (Roche Applied Science), and the cells were lysed at 4 °C for 10 min with lysis solution (50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 10 mm NaF, 20 mm sodium β-glycerol phosphate, 1 mm dithiothreitol, and protease inhibitors). Aliquots of total cell lysates containing equivalent amounts of total proteins were precleared for 4 h with protein A-Sepharose (Zymed Laboratories Inc.) at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitation was carried out with appropriate antibodies and protein A-Sepharose. After overnight incubation at 4 °C, immunocomplexes were isolated by centrifugation and washed four times with lysis buffer, analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, and detected with the enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Roche Applied Science) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Protein Turnover Analysis

HEK293T cells were transfected with corresponding plasmids in 12-well plates. The cells were then treated with 50 μg/ml of cycloheximide at 24 h post-transfection and were harvested at indicated time points. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblotting.

RESULTS

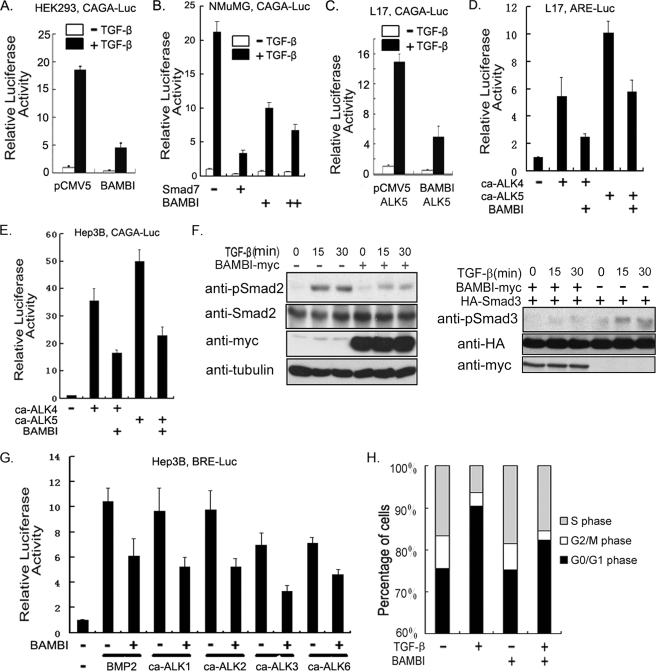

The Inhibitory Function of BAMBI in TGF-β Signaling Is Evolutionally Conserved

Previous studies demonstrated that BAMBI interferes with TGF-β signaling in both Xenopus embryos and mouse embryonic carcinoma P19 cells (24). To investigate whether the hBAMBI exerts a similarly inhibitory effect on TGF-β signaling, human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells were transfected with the TGF-β-responsive reporter CAGA-luciferase (38), together with or without hBAMBI cDNA. As shown in Fig. 1A, BAMBI overexpression inhibited the TGF-β-induced expression of CAGA-luciferase. This inhibitory effect of BAMBI on the transcriptional response of TGF-β was confirmed in the normal murine mammary gland epithelial NMuMG cells (Fig. 1B) and in ALK5-deficient L17 cells, which were derived from mink lung epithelial MvlLu cells (39), upon ALK5 expression (Fig. 1C). To explore whether hBAMBI has a more general effect on the transcriptional responses of TGF-β, the expression of another TGF-β-responsive reporter, ARE-luciferase (40), was tested in L17 cells. The expression of this reporter was stimulated by the constitutively active TGF-β type I receptor (ca-ALK5) or constitutively active activin type I receptor (ca-ALK4), but this stimulatory effect was impaired by BAMBI (Fig. 1D). Similar inhibitory effect on type I receptors was also observed in human hepatoma Hep3B cells with CAGA-luciferase (Fig. 1E) and ARE-luciferase (data not shown). In addition, overexpression of BAMBI attenuated TGF-β-induced phosphorylation of Smad2 in HeLa cells and Smad3 in HEK293T cells (Fig. 1F). Therefore, like its Xenopus homolog, hBAMBI negatively regulates TGF-β signaling.

FIGURE 1.

Human BAMBI interferes with TGF-β signaling. A, HEK293 cells transfected with plasmids encoding CAGA-luciferase (200 ng), Renilla (20 ng), and hBAMBI (100 ng) were treated with 100 pm TGF-β1 for 20 h and harvested for luciferase assay. In all of the reporter assay experiments, empty vectors were used to equalize total amount of plasmids in each well. B, Smad7 (50 ng) or BAMBI plasmids (100 or 200 ng) were transfected into NMuMG cells along with CAGA-luciferase and Renilla. After treatment with 100 pm TGF-β1 for 20 h, a luciferase assay was performed. C, L17 cells were transfected with CAGA-luciferase, Renilla luciferase, wild-type ALK5 (50 ng) as well as hBAMBI plasmids. Reporter assay was performed similarly as described for A. D, L17 cells were transfected with ARE-luciferase (300 ng), FoxH1 (150 ng), Renilla and constitutively active receptors ca-ALK4 (50 ng), ca-ALK5 (50 ng), or hBAMBI plasmids as indicated and harvested at 48 h post-transfection for luciferase assay. E, Hep3B cells were transfected with CAGA-luciferase, Renilla, and ca-ALK4, ca-ALK5, or hBAMBI plasmids as indicated and harvested at 48 h post-transfection for luciferase assay. F, HeLa (left panels) or HEK293T (right panels) cells transfected with BAMBI plasmids or control vectors were treated with 100 pm TGF-β1 at the indicated time points and harvested for phospho-Smad2 or phospho-Smad3 level detection by immunoblotting. G, Hep3B cells were transfected with BRE-luciferase (200 ng), Renilla, hBAMBI plasmids, and constitutively active type I receptors (50 ng each), as indicated. The cells were treated with or without BMP2 (25 ng/ml) for 20 h and then harvested at 48 h post-transfection for luciferase assay. H, NMuMG cells stably expressing hBAMBI or control vector were harvested for flow cytometry analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.” For luciferase assay, each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data represent the means ± S.D. after being normalized to Renilla activity.

Because Xenopus BAMBI functions as a general inhibitor for TGF-β family members (24), we then asked whether hBAMBI can suppress BMP signaling as well. As expected, hBAMBI attenuated the expression of BRE-luciferase induced by BMP2 or the constitutively active BMP receptors ca-ALK3, ca-ALK6, ca-ALK2, as well as ca-ALK1 in Hep3B cells (Fig. 1G).

To study the effect of BAMBI on TGF-β signaling in a physiological context, we generated a NMuMG cell line stably expressing hBAMBI. After serum starvation for 24 h, the cells were treated with or without 100 pm TGF-β1 for another 24 h and then subjected to cell cycle analysis with fluorescence-activated cell sorting. As shown in Fig. 1H, TGF-β treatment resulted in cell growth arrest in the G0/G1 phase, and this effect was attenuated by stably expression of hBAMBI. Together, these results suggest that hBAMBI acts as a general antagonist of TGF-β family members as Xenopus BAMBI does.

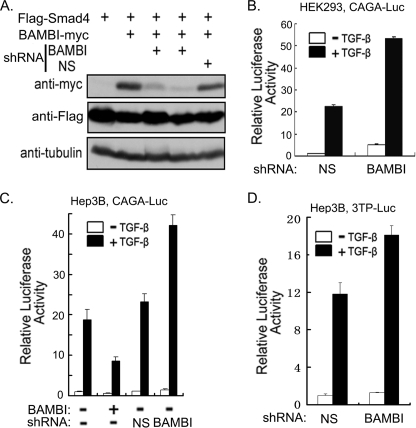

Knockdown of Endogenous hBAMBI Expression Promotes TGF-β Signaling

To further validate the function of BAMBI in regulating TGF-β signaling, we generated a shRNA construct against hBAMBI and confirmed its effectiveness in knocking down BAMBI expression in HEK293T cells (Fig. 2A). To investigate the role of endogenous BAMBI in TGF-β signaling, HEK293 cells were transfected with CAGA-luciferase together with BAMBI shRNA or control shRNA. As shown in Fig. 2B, BAMBI shRNA apparently enhanced the TGF-β-induced reporter expression. Consistent with it, BAMBI was expressed in HEK293 cells (data not shown). Similar results were obtained in Hep3B cells with CAGA-luciferase (Fig. 2C) or another TGF-β-responsive reporter p3TP-luciferase (41) (Fig. 2D). These data further support our observation that BAMBI is a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling at the endogenous level.

FIGURE 2.

TGF-β signaling is negatively regulated by endogenous BAMBI. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated constructs and harvested at 40 h post-transfection for immunoblotting. FLAG-tagged Smad4 was co-transfected to show the transfection efficiency and served as a negative control, and tubulin was used as a loading control. B–D, knockdown of endogenous BAMBI expression facilitates TGF-β-induced expression of reporters. HEK293 or Hep3B cells were transfected with CAGA-luciferase (200 ng) or p3TP-luciferase (200 ng) together with Renilla and hBAMBI plasmids (100 ng) or BAMBI shRNA (50 ng) as indicated. Then cells were treated with 100 pm TGF-β1 for 20 h before being harvested for luciferase assay. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data represent the means ± S.D. after being normalized to Renilla activity.

Human BAMBI Impairs TGF-β Receptor Complex Formation

Xenopus BAMBI has been demonstrated to inhibit TGF-β signaling by associating with TGF-β receptors and interfering with the formation of the functional receptor complex (24). Because hBAMBI is highly conserved with its Xenopus homolog at the amino acid level, it may attenuate TGF-β signaling by a similar mechanism. To examine this possibility, we assessed whether hBAMBI would interact with TGF-β family receptors. HEK293T cells were transfected with plasmid constructs encoding Myc-tagged hBAMBI and HA-tagged various type I receptors, and protein interaction was examined by anti-HA immunoprecipitation followed by anti-Myc immunoblotting. As shown in Fig. 3A, hBAMBI was immunoprecipitated by all the type I receptors examined. A similar experiment revealed that hBAMBI could also associate with the type II receptors of TGF-β, activin, and BMPs (data not shown). The interaction between ALK5 and hBAMBI was confirmed with endogenous proteins in both HeLa cells and Mv1Lu cells, and their interaction was enhanced by TGF-β treatment (Fig. 3B), suggesting that hBAMBI may exhibit a higher binding affinity with the active ALK5. To confirm this, we tested the interaction between BAMBI and wild-type, constitutively active (ca-ALK5), or kinase-deficient ALK5 mutants in HEK293T cells. Indeed, ca-ALK5 showed higher binding affinity to BAMBI, and kinase-deficient ALK5 bound to hBAMBI less strongly (Fig. 3C). Together, these data indicate that the BAMBI-ALK5 interaction is regulated by TGF-β signaling. We further mapped the binding region with hBAMBI deletion mutants and found that the intracellular domain (ICD) of hBAMBI mediated its interaction with ALK5 (Fig. 3D).

FIGURE 3.

BAMBI interferes with receptor heterocomplex formation. A, HEK293T cells were transfected with HA- or FLAG-tagged receptors and Myc-tagged hBAMBI. At 48 h post-transfection, the cells were harvested for anti-HA or anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by anti-Myc immunoblotting (IB). Protein expression was examined by immunoblotting. B, HeLa cell lysates or Mv1Lu cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with control rabbit IgG or anti-ALK5 antibody followed by anti-BAMBI immunoblotting. Before harvesting, the cells were treated with or without 100 pm TGF-β1 for 2 h. C, constitutively active ALK5 (ca-ALK5) has a higher binding affinity to hBAMBI than wild-type or kinase-deficient ALK5 (KR). Protein interaction was examined as above. D, a scheme shows the structure of the full length, ICD, or extracellular domain (ECD) of BAMBI. They all contain the transmembrane domain and the signal peptide sequence. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated constructs, and cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation-immunoblotting analysis. E, BAMBI interferes with the receptor complex formation. Protein interaction was examined as above. F, knockdown of BAMBI expression enhances the ALK5-TβRII interaction. HeLa cells transfected with BAMBI shRNA or control shRNA were treated with 100 pm TGF-β1 for 2 h before harvesting. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with control IgG or anti-ALK5 antibody followed by anti-TβRII immunoblotting. WCL, whole cell lysate.

Then we tested whether hBAMBI can interfere with the receptor heterocomplex formation. The immunoprecipitation-immunoblotting experiment showed that co-expression of BAMBI impaired the complex formation between ALK5 and TβRII (Fig. 3E). This effect was further confirmed at the endogenous level as BAMBI knockdown enhanced the interaction between ALK5 and TβRII in HeLa cells (Fig. 3F). Together, these results suggest that hBAMBI, like its Xenopus homolog, represses TGF-β signaling by binding to its receptors and interfering with the formation of the functional receptor complex.

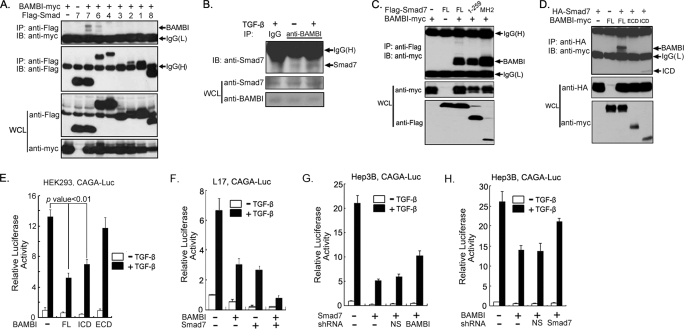

Human BAMBI Cooperates with Smad7 to Inhibit TGF-β Signaling

To explore whether BAMBI functions at the Smad level to influence TGF-β signaling, we examined whether BAMBI interacts with Smad proteins. An immunoprecipitation-immunoblotting experiment showed that hBAMBI could associate with Smad7 and Smad6 to a lesser extent (Fig. 4A). The interaction between BAMBI and Smad7 was also detected with endogenous proteins in HeLa cells, and this interaction was enhanced by TGF-β treatment (Fig. 4B). Domain mapping experiments showed that both the MH1 and the MH2 domains of Smad7 interact with hBAMBI, and the BAMBI ICD mediated its interaction with Smad7 (Fig. 4, C and D). Consistently, the BAMBI ICD could interfere with TGF-β signaling, whereas the extracellular domain had no significant effect (Fig. 4E).

FIGURE 4.

BAMBI cooperates with Smad7 to inhibit TGF-β signaling. A, BAMBI interacts with Smad6 and Smad7. HEK293T cells were transfected with different FLAG-tagged Smad constructs as well as Myc-tagged hBAMBI and harvested for protein interaction analysis at 48 h post-transfection. B, TGF-β promotes endogenous BAMBI-Smad7 interaction. HeLa cells were treated with or without 100 pm TGF-β1 for 2 h before harvesting. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with control IgG or anti-BAMBI antibody followed by anti-Smad7 immunoblotting (IB). C and D, mapping the interaction domain of Smad7 and BAMBI. HEK293 cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and harvested for protein-protein interaction assay as above. E, the BAMBI ICD has an inhibitory effect on the TGF-β-induced expression of CAGA-luciferase. HEK293 cells transfected with CAGA-luciferase, Renilla, and hBAMBI deletion constructs were treated with TGF-β1 for 20 h and harvested for report assay. F–H, BAMBI and Smad7 cooperate with each other to inhibit TGF-β signaling. L17 cells or Hep3B cells were transfected with CAGA-luciferase, Renilla, and other constructs as indicated, treated with TGF-β1 for 20 h, and then harvested for report assay. Each experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data represent the means ± S.D. after being normalized to Renilla activity. WCL, whole cell lysate.

Smad7 can directly interact with the activated type I receptors and inhibit TGF-β signaling (19–21, 42–44). Because both Smad7 and hBAMBI negatively regulate TGF-β signaling, we hypothesized that the two proteins may cooperate with each other to block TGF-β signaling. Indeed, hBAMBI and Smad7 together repressed the TGF-β-induced expression of CAGA-luciferase more dramatically than either single one does (Fig. 4F). Furthermore, hBAMBI knockdown could reverse the inhibitory effect of Smad7 to some extent in Hep3B cells (Fig. 4G), and reduction of Smad7 expression also had a similar effect on the inhibitory function of hBAMBI (Fig. 4H). Collectively, these results suggest that hBAMBI could cooperate with Smad7 in antagonizing TGF-β signaling.

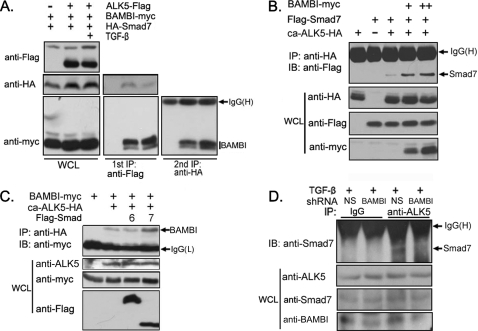

Human BAMBI Forms a Ternary Complex with ALK5 and Smad7 in Response to TGF-β

Because TGF-β signaling promotes the association of hBAMBI with both Smad7 and ALK5, it is possible that they are engaged in the same complex. To examine this possibility, we co-expressed ALK5-FLAG, BAMBI-Myc, and HA-Smad7 in HEK293T cells and investigated the ternary complex formation between these proteins via two-step immunoprecipitation. ALK5 and associated proteins were firstly purified by anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation and eluted with FLAG peptide. The eluted immunoprecipitant was then subjected to anti-HA immunoprecipitation. As shown in Fig. 5A, both Smad7 and BAMBI were co-precipitated with ALK5, and BAMBI bound to Smad7 after the second immunoprecipitation. Furthermore, TGF-β treatment enhanced the association of BAMBI with both ALK5 and Smad7, suggesting that TGF-β promotes the ternary complex formation. This is consistent with the fact that BAMBI elevated the interaction between ca-ALK5 and Smad7 in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 5B). In addition, the interaction between ca-ALK5 and BAMBI was also promoted by Smad7 but not by Smad6 (Fig. 5C). Knockdown of BAMBI attenuated the binding of endogenous Smad7 to ALK5 in HeLa cells (Fig. 5D). These results together suggested that BAMBI, Smad7, and ALK5 form a ternary complex that could be enhanced by TGF-β and that Smad7 and hBAMBI cooperate with each other in the formation of this complex.

FIGURE 5.

BAMBI forms a ternary complex with ALK5 and Smad7. A, TGF-β promotes the ternary complex formation between hBAMBI, Smad7, and ALK5. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated constructs, treated with or without TGF-β1 for 2 h, and harvested for the first immunoprecipitation (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody. Then the immunocomplexes were eluted by FLAG peptide and subjected to the second immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody followed by anti-Myc immunoblotting (IB, right panel). Aliquots of whole cell lysates and the first immunoprecipitants were analyzed by anti-HA or anti-Myc immunoblotting (left and middle panels). B, BAMBI promotes the Smad7-ALK5 association. C, Smad7 enhances the BAMBI-ALK5 interaction. D, knockdown of BAMBI attenuates the interaction between endogenous ALK5 and Smad7. HeLa cells transfected with shRNA constructs as indicated were treated with 100 pm TGF-β1 for 2 h, and cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with control IgG or anti-ALK5 antibody followed by anti-Smad7 immunoblotting. WCL, whole cell lysate.

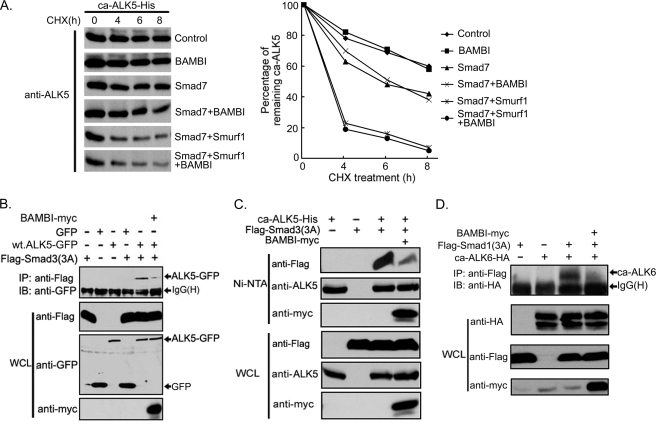

Human BAMBI Interferes with Smad3 Recruitment to ALK5

Smad7 antagonizes TGF-β signaling by different mechanisms (20, 21). To explore how hBAMBI synergizes with Smad7 to inhibit TGF-β signaling, we examined the half-life of ca-ALK5 when co-expressed with Smad7, Smurf1, or BAMBI in the presence of cycloheximide to block protein biosynthesis. Consistent with previous reports, Smad7 and Smurf1 induced ALK5 degradation (Fig. 6A). However, hBAMBI alone had little effect on the turnover of ALK5 and did not promote Smad7/Smurf1-induced degradation of ca-ALK5 further.

FIGURE 6.

BAMBI inhibits the interaction between ALK5 and Smad3. A, BAMBI has no effect on ca-ALK5 turnover. HEK293T cells were transfected with His-tagged ca-ALK5 with or without Smad7, Smurf1, or hBAMBI and treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated times, and the cells were harvested for anti-ALK5 immunoblotting (IB). The data were quantitated (right panel). B–D, BAMBI interferes with the association of R-Smads with type I receptors. HEK293T cells were transfected with indicated plasmid constructs, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG antibody followed by anti-green fluorescent protein immunoblotting (B), precipitated with nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads followed by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies (C), or immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody followed by anti-HA immunoblotting (D). Protein expression levels (whole cell lysate (WCL)) were examined by immunoblotting. All of these experiments were repeated, and similar results were obtained. wt, wild type.

Then we tested whether hBAMBI interferes with the interaction between ALK5 and R-Smads. To facilitate the detection of the interaction between receptor and Smad3, we used mutant Smad3(3A), in which the receptor-phosphorylated serine residues at the C-terminal end were mutated to alanines. As shown in Fig. 6B, Smad3(3A) could associate with green fluorescent protein-tagged ALK5, but this association was attenuated by hBAMBI. Similar result was obtained by His-tagged ALK5 (Fig. 6C). In addition, hBAMBI inhibited the interaction between the Smad1 C-tail phosphorylation-defective mutant Smad1(3A) and the constitutively active BMP type I receptor ca-ALK6 (Fig. 6D). Together these data suggest that the engagement of hBAMBI in a complex with active type I receptors and Smad7 inhibits the binding of R-Smads to the type I receptors and thereby blocks R-Smad activation.

DISCUSSION

The TGF-β family members play pivotal roles in embryo development and tissue homeostasis. Although the canonical Smad-mediated signaling pathway is relatively simple, it is precisely controlled at different levels from the availability and activation of extracellular ligands, the activity and stability of membrane receptors, to the activity, location, and stability of Smad proteins in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus (14, 15, 21, 45–47). Here, we demonstrated that hBAMBI, like its Xenopus homolog, functions as a general antagonist to attenuate the transcriptional activity of TGF-β/BMPs and inhibit TGF-β-induced R-Smad phosphorylation and cell growth arrest, indicating that the inhibitory activity of BAMBI on TGF-β signaling is evolutionally conserved.

Although the possible function of BAMBI in TGF-β signaling has been examined in different animal models such as Xenopus (24), zebrafish (25), rat (23), and mouse (22), our understanding of the molecular mechanism underlying its function is still limited. It has been shown that Xenopus BAMBI can bind to TGF-β receptors and interfere with the heterocomplex formation between the type I and type II receptors (24). Here, we confirmed this mechanism with hBAMBI. Moreover, this study has discovered an additional mechanism whereby BAMBI cooperates with Smad7 to inhibit TGF-β signaling.

Smad7 is a well characterized antagonist of TGF-β signaling. It was found to directly interact with the active type I receptors in competition with R-Smads and thus inhibit the activation of R-Smads (19, 42), to recruit the ubiquitin E3 ligases Smurf1 or Smurf2 and lead to the ubiquitination and degradation of ALK5 (48–50), to promote receptor dephosphorylation via protein phosphatase 1c (51), or to block functional Smad-DNA complex formation in the nucleus (37). In this study, we found that hBAMBI also interacts with inhibitory Smads Smad6 and Smad7, and the interaction between hBAMBI and Smad7 was enhanced by TGF-β treatment. TGF-β promoted the association of hBAMBI with Smad7, and hBAMBI exhibited a higher binding affinity to active ALK5. Our study further demonstrated that hBAMBI, Smad7, and ALK5 form a ternary complex. Interestingly, unlike Smad7 and Smurfs, hBAMBI does not affect ALK5 turnover nor further promote Smad7/Smurf1-induced degradation of ALK5. Rather hBMABI inhibits the interaction between Smad3 and ALK5 and interferes with Smad3 phosphorylation. Therefore, our data suggest that BAMBI could exploit dual mechanisms to interfere with TGF-β signaling, and these two mechanisms may work cooperatively. Because BAMBI can also interact with Smad6, and both of them are negative regulators of BMP signaling, it is possible that BAMBI and Smad6 might cooperatively inhibit BMP signaling in similar manners. Indeed, overexpression of BAMBI inhibited the binding of Smad1(3A) with the constitutive active BMP type I receptor ca-ALK6, suggesting that BAMBI utilizes similar mechanisms to function as a general antagonist of the TGF-β family members.

Despite a recent study reporting that BAMBI is dispensable for mouse embryo development and postnatal survival (28), other studies have underlined the possible important roles of hBAMBI in several pathological processes such as tumorigenesis and fibrogenesis. BAMBI was firstly reported to be a gene whose expression was reversely correlated with metastasis progression of human melanomas (33). BAMBI was also found to counteract the effect of TGF-β on cell growth and invasion of human gastric carcinoma cell lines (35) and bladder cancer cells (34). The expression of BAMBI is significantly up-regulated in most colorectal and hepatocellular carcinomas, and this up-regulation is mediated by β-catenin (31). Furthermore, overexpression of BAMBI attenuated TGF-β signaling in these tumor cells, suggesting that β-catenin can promote the formation of colorectal and hepatocellular tumors by interfering with TGF-β-mediated growth arrest via BAMBI. A recent report also indicated that BAMBI might be involved in hepatic fibrogenesis (36). Toll-like receptor 4 and lipopolysaccharide sensitize hepatic stellate cells to TGF-β signaling by down-regulating the expression of BAMBI via a MyD88-NF-κB-dependent pathway. These studies suggest that the appropriate negative regulation of TGF-β by BAMBI is important for tissue homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. G. W. Swart for hBAMBI/nma cDNA and also to Ziying Liu for critical reading of manuscript.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30671033 and 90713045 and 973 Program Grants 2006CB943401 and 2006CB910102).

- TGF

- transforming growth factor

- BMP

- bone morphogenic protein

- ALK5

- activin receptor-like kinase 5 (TβRI)

- shRNA

- small hairpin RNA

- ca

- constitutively active

- ICD

- intracellular domain

- HA

- hemagglutinin

- ARE

- activin-responsive element.

REFERENCES

- 1.Derynck R., Zhang Y. E. (2003) Nature 425, 577–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massagué J. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 753–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Massagué J., Blain S. W., Lo R. S. (2000) Cell 103, 295–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miyazono K., Suzuki H., Imamura T. (2003) Cancer Sci. 94, 230–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goumans M. J., Liu Z., ten Dijke P. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 116–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padua D., Massagué J. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 89–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watabe T., Miyazono K. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 103–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng X. H., Derynck R. (2005) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 21, 659–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Massagué J., Seoane J., Wotton D. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 2783–2810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moustakas A., Souchelnytskyi S., Heldin C. H. (2001) J. Cell Sci. 114, 4359–4369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmierer B., Hill C. S. (2007) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 970–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ten Dijke P., Hill C. S. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 265–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo X., Wang X. F. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 71–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hill C. S. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 36–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lönn P., Morén A., Raja E., Dahl M., Moustakas A. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 21–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derynck R., Akhurst R. J., Balmain A. (2001) Nat. Genet. 29, 117–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massagué J., Chen Y. G. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 627–644 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyazono K. (2000) J. Cell Sci. 113, 1101–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakao A., Afrakhte M., Morén A., Nakayama T., Christian J. L., Heuchel R., Itoh S., Kawabata M., Heldin N. E., Heldin C. H., ten Dijke P. (1997) Nature 389, 631–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park S. H. (2005) J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 38, 9–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan X., Liu Z., Chen Y. (2009) Acta. Biochim. Biophys Sin. 41, 263–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grotewold L., Plum M., Dildrop R., Peters T., Rüther U. (2001) Mech. Dev. 100, 327–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loveland K. L., Bakker M., Meehan T., Christy E., von Schönfeldt V., Drummond A., de Kretser D. (2003) Endocrinology 144, 4180–4186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onichtchouk D., Chen Y. G., Dosch R., Gawantka V., Delius H., Massagué J., Niehrs C. (1999) Nature 401, 480–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tsang M., Kim R., de Caestecker M. P., Kudoh T., Roberts A. B., Dawid I. B. (2000) Genesis 28, 47–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higashihori N., Song Y., Richman J. M. (2008) Dev. Dyn. 237, 1500–1508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karaulanov E., Knöchel W., Niehrs C. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 844–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen J., Bush J. O., Ovitt C. E., Lan Y., Jiang R. (2007) Genesis 45, 482–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xi Q., He W., Zhang X. H., Le H. V., Massagué J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 1146–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sekiya T., Oda T., Matsuura K., Akiyama T. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 320, 680–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sekiya T., Adachi S., Kohu K., Yamada T., Higuchi O., Furukawa Y., Nakamura Y., Nakamura T., Tashiro K., Kuhara S., Ohwada S., Akiyama T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 6840–6846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin Z., Gao C., Ning Y., He X., Wu W., Chen Y. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33053–33058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Degen W. G., Weterman M. A., van Groningen J. J., Cornelissen I. M., Lemmers J. P., Agterbos M. A., Geurts van Kessel A., Swart G. W., Bloemers H. P. (1996) Int. J. Cancer 65, 460–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Khin S. S., Kitazawa R., Win N., Aye T. T., Mori K., Kondo T., Kitazawa S. (2009) Int. J. Cancer 125, 328–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sasaki T., Sasahira T., Shimura H., Ikeda S., Kuniyasu H. (2004) Oncol. Rep. 11, 1219–1223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seki E., De Minicis S., Osterreicher C. H., Kluwe J., Osawa Y., Brenner D. A., Schwabe R. F. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 1324–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang S., Fei T., Zhang L., Zhang R., Chen F., Ning Y., Han Y., Feng X. H., Meng A., Chen Y. G. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 4488–4499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dennler S., Itoh S., Vivien D., ten Dijke P., Huet S., Gauthier J. M. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 3091–3100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boyd F. T., Massagué J. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 2272–2278 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang H. C., Murtaugh L. C., Vize P. D., Whitman M. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 5965–5973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cárcamo J., Weis F. M., Ventura F., Wieser R., Wrana J. L., Attisano L., Massagué J. (1994) Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 3810–3821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayashi H., Abdollah S., Qiu Y., Cai J., Xu Y. Y., Grinnell B. W., Richardson M. A., Topper J. N., Gimbrone M. A., Jr., Wrana J. L., Falb D. (1997) Cell 89, 1165–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Imamura T., Takase M., Nishihara A., Oeda E., Hanai J., Kawabata M., Miyazono K. (1997) Nature 389, 622–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Souchelnytskyi S., Nakayama T., Nakao A., Morén A., Heldin C. H., Christian J. L., ten Dijke P. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 25364–25370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wrighton K. H., Lin X., Feng X. H. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 8–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deheuninck J., Luo K. (2009) Cell Res. 19, 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Itoh S., ten Dijke P. (2007) Curr. Opin Cell Biol. 19, 176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kavsak P., Rasmussen R. K., Causing C. G., Bonni S., Zhu H., Thomsen G. H., Wrana J. L. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 1365–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ebisawa T., Fukuchi M., Murakami G., Chiba T., Tanaka K., Imamura T., Miyazono K. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12477–12480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suzuki C., Murakami G., Fukuchi M., Shimanuki T., Shikauchi Y., Imamura T., Miyazono K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 39919–39925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shi W., Sun C., He B., Xiong W., Shi X., Yao D., Cao X. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 164, 291–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]