Abstract

ADP responses underlie therapeutic approaches to many cardiovascular diseases, and ADP receptor antagonists are in widespread clinical use. The role of ADP in platelet biology has been extensively studied, yet ADP signaling pathways in endothelial cells remain incompletely understood. We found that ADP promoted phosphorylation of the endothelial isoform of nitric-oxide synthase (eNOS) at Ser1179 and Ser635 and dephosphorylation at Ser116 in cultured endothelial cells. Although eNOS activity was stimulated by both ADP and ATP, only ADP signaling was significantly inhibited by the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS 2179 or by knockdown of P2Y1 using small interfering RNA (siRNA). ADP activated the small GTPase Rac1 and promoted endothelial cell migration. siRNA-mediated knockdown of Rac1 blocked ADP-dependent eNOS Ser1179 and Ser635 phosphorylation, as well as eNOS activation. We analyzed pathways known to regulate eNOS, including phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt, ERK1/2, Src, and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-β (CaMKKβ) using the inhibitors wortmannin, PD98059, PP2, and STO-609, respectively. None of these inhibitors altered ADP-modulated eNOS phosphorylation. In contrast, siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) inhibited ADP-dependent eNOS Ser635 phosphorylation and eNOS activity but did not affect eNOS Ser1179 phosphorylation. Importantly, the AMPK enzyme inhibitor compound C had no effect on ADP-stimulated eNOS activity, despite completely blocking AMPK activity. CaMKKβ knockdown suppressed ADP-stimulated eNOS activity, yet inhibition of CaMKKβ kinase activity using STO-609 failed to affect eNOS activation by ADP. These data suggest that the expression, but not the kinase activity, of AMPK and CaMKKβ is necessary for ADP signaling to eNOS.

Introduction

Purine nucleotides have long been known to play critical intracellular roles in nucleic acid synthesis and energy metabolism, yet these nucleotides also serve as important extracellular signaling molecules. Nucleotides such as ADP and ATP regulate vascular homeostasis through their activation of a family of selective cell surface receptors located on platelets, endothelial cells, and vascular smooth muscle cells (1). Receptors for purine nucleotides include the G protein-coupled P2Y receptors and the ligand-gated P2X ion channel receptors. Upon binding to their cognate receptors, purine nucleotides exert their effects via multiple second messenger pathways, including mobilization of intracellular calcium and alterations in cyclic nucleotides.

Receptors for extracellular nucleotides have been found in many different cell types (2), and purinergic signaling is especially important in the maintenance of vascular tone and function. More than 80 years ago, purine nucleotides were found to cause vasodilatation and hypotension (3), yet the signaling pathways activated by purinergic receptors in the vasculature have turned out to be complex and are not fully understood. Different vascular responses are elicited depending on the source of the nucleotide agonist, the target cell, and the receptor subtype. To date, most attention has been focused on the roles of ATP and UTP in the vasculature. For example, ATP has been shown to promote vasoconstriction through P2X1 receptors located on vascular smooth muscle cells (4), whereas in endothelial cells, ATP-dependent activation of P2X4 receptors promotes vasodilation in the context of shear stress (5). Activation of P2Y2 receptors by ATP and UTP contributes to vascular smooth muscle cell contraction, as well as vascular smooth muscle cell and endothelial cell migration (4, 6, 7). Recent work has shown that ATP promotes activation of eNOS2 (8). In contrast to the numerous studies of vascular responses to ATP, ADP signaling in the vessel wall has not been extensively investigated. There have been recent studies showing that ADP mediates vasoconstriction via P2Y12 receptors in vascular smooth muscle cells and stimulates endothelial cell migration through P2Y1 receptor-mediated pathways (9, 10). However, ADP signaling pathways in the endothelium remain incompletely characterized. Importantly, endothelial cells can respond to ADP released by red blood cells and platelets, and endothelial cells themselves can release purine nucleotides in an autocrine signaling pathway (4, 11). The proximity of the endothelium to cellular sources of ADP, as well as the widespread use of ADP receptor antagonists in cardiovascular therapeutics, led us to explore the molecular mechanisms mediating these paracrine and autocrine effects of ADP in endothelial cells. The present studies explored the hypothesis that ADP modulates nitric oxide-dependent pathways involving eNOS.

eNOS is a key determinant of vascular homeostasis and appears to be a plausible target for ADP-modulated signaling responses. eNOS is a Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent enzyme that is activated in response to the stimulation of a number of different Ca2+-mobilizing cell surface receptors (12). Regulation of eNOS is also achieved by phosphorylation of multiple sites in the protein (13): phosphorylation at Ser1179 or Ser635 activates eNOS, whereas phosphorylation at Thr497 or Ser116 is associated with inhibition of enzyme activity (the residues refer to the sequence of the well characterized bovine eNOS; corresponding human eNOS residues are Ser1177, Ser633, Thr495, and Ser114). The regulation of eNOS Ser1179 has been studied most extensively: many protein kinases, including protein kinase Akt (14), AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) (15), cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase/protein kinase A (PKA) (16), and PLC (17), as well as cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase (18), modulate eNOS activity, at least in part through regulation of this Ser1179 phosphorylation site. Other kinase pathways, including various protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms (19, 20), members of the MAPK family (21), and calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-β (CaMKKβ) (22), have also been implicated in modulation of eNOS phosphorylation. Additionally, the small GTPase Rac1, an important regulator of cell migration and the actin cytoskeleton (23, 24), appears to be an essential upstream modulator of receptor-regulated phosphorylation and activation of eNOS (25). Activation of different cell surface receptors elicits distinct kinase pathways associated with eNOS activation, yet the roles of these various kinase pathways or of Rac1 in mediating endothelial ADP responses have not been fully elucidated. Significantly, nitric oxide (NO) synthesized by activated eNOS promotes the relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells, inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation/migration, and blocks platelet aggregation (26). NO also regulates endothelial cell survival and migration (27). Given the overlap in physiological responses of vascular cells to NO and ADP, we considered eNOS a plausible candidate mediator of ADP effects on the endothelium.

The present studies investigated the signaling pathways involved in ADP-induced modulation of eNOS and cell migration in cultured endothelial cells. We provide evidence that distinguishes ADP from ATP responses in these cells and show data to suggest that it is the expression, rather than the kinase activity, of AMPK and CaMKKβ that is necessary for the ability of ADP to regulate eNOS activity. Furthermore, we establish Rac1 as a critical mediator of ADP signaling to eNOS, as well as ADP-induced cell migration, and we propose a critical role for Rac1 in purinergic control of NO-dependent pathways and cellular responses in the vascular endothelium.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from HyClone Laboratories (Logan, UT). All other cell culture reagents, media, and Lipofectamine 2000 were from Invitrogen. Sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) and PP2 were purchased from BIOMOL (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), wortmannin, PD98059, cyclosporine, STO-609, and compound C were from Calbiochem. Anti-phospho-eNOS (Ser116) and anti-Rac1 antibodies were from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY). Polyclonal antibodies against phospho-eNOS (Ser1177), phospho-Akt (Ser473), Akt, phospho-AMPKα (Thr172), AMPK, phospho-acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) (Ser79), ACC, phospho-GSK3β (Ser9), phospho-ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), and ERK1/2 were from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Monoclonal antibodies against GSK3β, eNOS, CaMKKβ, and phospho-eNOS (Ser633) were from BD Transduction Laboratories. The Rac1 activity assay kit was purchased from Cytoskeleton, Inc. (Denver, CO). Protein G-Sepharose beads were from Invitrogen. SuperSignal chemiluminescence detection reagents and secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were from Pierce Biotechnology. All other reagents were from Sigma.

Cell Culture and Transfection

BAEC were obtained from Genlantis (San Diego, CA) and maintained in culture in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with fetal bovine serum (10%, v/v) as described (28). Cells were plated onto gelatin-coated culture dishes and studied prior to cell confluence between passages 6 and 8. siRNA transfections were performed as described previously (29). 30 nm siRNA was transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (0.15%, v/v) following the protocol provided by the manufacturer 24 h after cells were split at a 1:8 ratio. Lipofectamine 2000 was then removed by changing into fresh medium containing 10% FBS 5 h after transfection.

Cell Treatments and Immunoblot Analysis

ADP, ATP, MRS 2179, and epinephrine were solubilized in water and stored at −20 °C. S1P was solubilized in methanol and stored at −20 °C. The same volume of methanol was used as vehicle control, and the final concentration of methanol did not exceed 0.4% (v/v). VEGF was solubilized in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin and stored at −80 °C. Wortmannin, U-73122, PP2, PD98059, STO-609, and compound C were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide and kept at −20 °C. Where indicated, dimethyl sulfoxide 0.1% (v/v) was used as vehicle control. After drug treatments, lysates from BAEC were prepared using a cell lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.025% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA, 2 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm NaF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml antipain, 2 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, and 2 μg/ml lima trypsin inhibitor). Immunoblot analyses of protein expression and phosphorylation were assessed as described previously (30). Determinations of protein abundance using immunoblot analyses were quantitated using a ChemiImager HD4000 (AlphaInnotech, San Leandro, CA).

Duplex siRNA Targeting Constructs

Experimental oligonucleotides were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). We designed a P2Y1 receptor duplex siRNA construct corresponding to positions 639–657 from the open reading frame of bovine P2Y1: 5′-CCGUGUACAUGUUCAACUUdTdT-3′ (GenBankTM accession number NM_174410.2). siRNA constructs targeting CaMKKβ, AMPKα1, PKA, Rac1, and eNOS have been previously described in detail and validated (25, 30, 31). The nonspecific control siRNA 5′-AUUGUAUGCGAUCGCAGAC-dTdT-3′ was from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO).

eNOS Activity Assay

eNOS activity was quantitated by measuring the formation of l-[3H]citrulline from l-[3H]arginine as described previously (32). Briefly, the reaction was initiated in cultured BAEC by adding l-[3H]arginine (10 μCi/ml, diluted with unlabeled l-arginine to give a final concentration of 10 μm) plus various drug treatments. Each treatment was performed in triplicate cultures, which were analyzed in duplicate. NOS activity, measured as l-citrulline formation, was expressed as pmol of l-citrulline produced/mg of cellular protein/min.

Rac1 Activity Assay

BAEC in 100-mm dishes were treated with agonists as indicated, and cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. The Rac1 activity assay was performed according to the manufacturer's protocol. 2 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm NaF, 0.1% SDS, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml antipain, 2 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, and 2 μg/ml lima trypsin inhibitor were added to the lysis buffer as recommended by the manufacturer. Pulldown of the GTP-bound active form of Rac1 was performed by incubating the cell lysates with glutathione S-transferase fusion protein corresponding to the p21-binding domain of PAK-1 bound to glutathione-agarose. The beads were washed once with washing buffer provided in the assay kit, and the proteins bound to the beads were eluted with Laemmli sample buffer and analyzed for the amount of GTP-bound Rac in immunoblots probed with a Rac monoclonal antibody supplied by the manufacturer.

Cell Migration Assay

Cell migration was assayed using a Transwell cell culture chamber containing polycarbonate membrane inserts with 8-μm pore size (Corning Costar Corp.) BAEC were transfected with control or specific siRNA as indicated, and experiments were performed 48 h after transfection. 18 h prior to experimentation, the medium was changed, and cells were starved in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 0.4% FBS. Cells were incubated with trypsin to obtain a monodispersed suspension, and 5 × 104 cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 0.4% FBS were added to the upper Transwell chamber. The bottom chamber was filled with 600 μl of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 0.4% FBS, and the assembly was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C to allow cells to adhere to the membrane. Vehicle, S1P, or ADP was added to the lower chamber, and the chambers were incubated at 37 °C overnight to allow cell migration. The Transwell inserts were transferred into a new plate containing 1 ml of 0.05% trypsin-EDTA solution to detach the cells from the membrane. Cells in the lower chamber were counted with a hemocytometer. Each treatment was performed in triplicate, and each sample was counted twice in four 4 × 4 square fields.

Cell Proliferation Assay

To assess cell proliferation, BAEC were seeded onto 24-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells/well; each determination was measured in triplicate in two independent experiments. Cells were treated with 50 μm ADP or vehicle overnight and labeled for 4 h with [3H]thymidine (1 μCi/well). Cells were then washed with phosphate-buffered saline, fixed with methanol, precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, and washed with water; incorporation of [3H]thymidine was determined in a scintillation counter.

Co-immunoprecipitation Assay

BAEC were harvested by scraping in phosphate-buffered saline containing phosphatase inhibitors (2 mm NaVO3 and 1 mm NaF), pelleted by centrifugation, and then resuspended in OG lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 60 mm octyl glucopyranoside, 125 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm EGTA, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 2 mm NaVO3, 1 mm NaF, 20 μg/ml leupeptin, 20 μg/ml antipain, 20 μg/ml soybean trypsin inhibitor, and 20 μg/ml lima bean trypsin inhibitor). Suspensions were rotated end over end at 4 °C for 20 min and then centrifuged at 14,000 × g. The supernatant was precleared by incubation with Protein G-Sepharose beads (Invitrogen) for 30 min at 4 °C followed by incubation for 1.5 h at 4 °C with a previously characterized rabbit eNOS polyclonal antiserum (33, 34) at a final dilution of 1:100. Protein G-Sepharose beads were then added for 1 h. After 1 h, immunoprecipitated complexes were washed three times in OG lysis buffer, eluted from the beads in Laemmli sample buffer, boiled for 10 min at 95 °C, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and probed in immunoblots as shown.

Other Methods

All experiments were performed at least three times. Mean values for experiments were expressed as mean ± S.E. Statistical differences were assessed by analysis of variance. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

ADP-dependent Phosphorylation Responses in Endothelial Cells

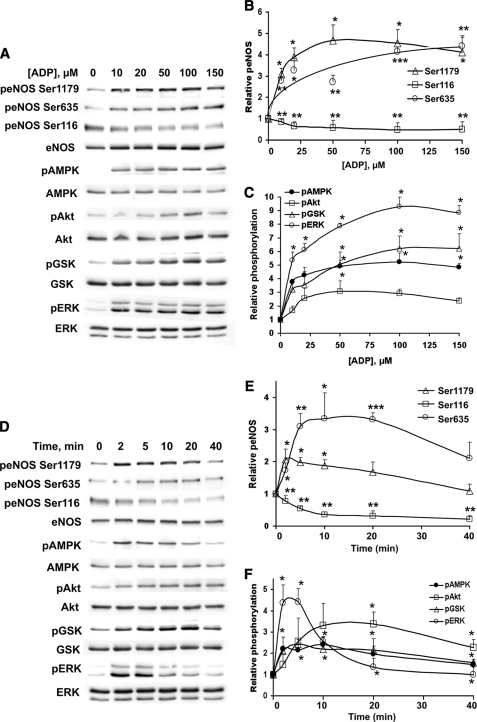

Fig. 1 shows the effects of ADP on the phosphorylation of several key endothelial signaling proteins. ADP-treated endothelial cells were analyzed in immunoblots probed with phosphorylation state-specific antibodies directed against eNOS, AMPK, Akt, GSK3β, and ERK1/2. In each case, the immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with antibodies directed against the corresponding total protein to verify equal loading under the different conditions studied. ADP promoted the dose-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS at residues Ser1179 and Ser635, AMPK (Thr172), kinase Akt (Ser473), GSK3β (Ser9), and ERK1/2 (Thr202/Tyr204), as well as dephosphorylation of eNOS at Ser116 (Fig. 1, A–C). The dose response for these ADP-modulated phosphorylation responses demonstrated an EC50 of ∼15 μm, a concentration that is within the physiological range of ADP in plasma (35, 36). The time course of these ADP-dependent phosphorylation responses is shown in Fig. 1, D–F. The addition of 15 μm ADP to BAEC resulted in an increase in the phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 within 2 min of agonist addition. ADP also robustly stimulated the phosphorylation of AMPK, GSK3β, and ERK1/2 with a similar temporal pattern. The peak of ADP-promoted phosphorylation of Akt and eNOS Ser635 was reached only at ∼15 min after agonist addition. All of these phosphorylation responses returned close to basal levels by 40 min. However, ADP-promoted dephosphorylation of eNOS at Ser116, which occurred within 2 min of adding ADP to the cells, persisted throughout the time course studied and achieved a persistent 80% decrease in phosphorylation. Together, these data indicate that ADP modulates the reversible phosphorylation of multiple residues on eNOS, as well as critical residues on AMPK, Akt, GSK3β, and ERK1/2 in endothelial cells.

FIGURE 1.

Dose response and time course for ADP-mediated phosphorylation responses in endothelial cells. Lysates prepared from ADP-treated BAEC were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed in immunoblots probed with antibodies directed against phospho-eNOS Ser1179, phospho-eNOS Ser635, phospho-eNOS Ser116, phospho-AMPK, phospho-Akt, phospho-GSK3β, and phospho-ERK1/2. Equal loading was confirmed by immunoblotting with antibodies directed against eNOS, AMPK, Akt, GSK3β, and ERK1/2. Shown on the left are representative immunoblots, and on the right are quantitative plots derived from pooled data. Each point in the graphs represents the mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments that yielded similar results. * indicates p < 0.05. ** indicates p < 0.01. A, BAEC were treated with the indicated concentrations of ADP for 5 min. B, quantitative analysis of phospho-eNOS as a function of concentration. C, quantitation of phospho-AMPK, phospho-Akt, phospho-GSK3β, and phospho-ERK1/2 as a function of ADP concentration. D, BAEC were treated with 15 μm ADP for the indicated times. E, quantitation of phospho-eNOS as a function of treatment time. F, quantitative analysis of phospho-AMPK, phospho-Akt, phospho-GSK3β, and phospho-ERK1/2 abundance as a function of treatment time. p, phospho.

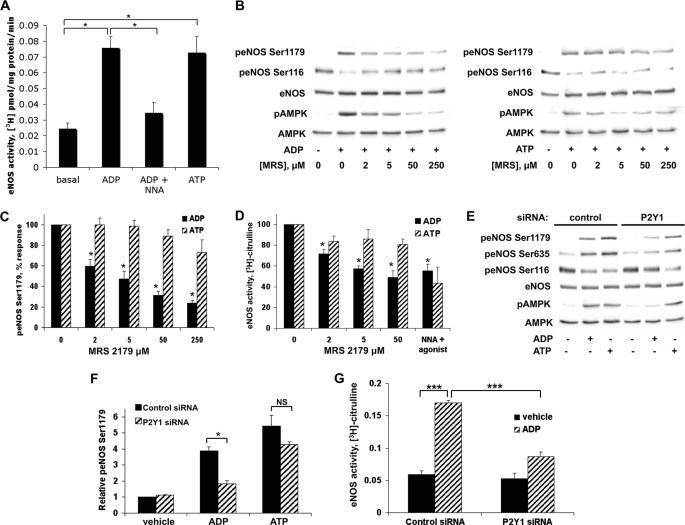

ADP, but Not ATP, Signaling to eNOS Is Mediated by P2Y1 Receptor

Our finding such robust phosphorylation responses to ADP (Fig. 1) led to our performing experiments to determine the receptor subtype mediating the ADP response. This is particularly important in the context of the well known ATP responses in the vascular wall: both ATP and ADP are abundant, and ATP can easily be converted to ADP by ectonucleotidases. Indeed, we found that both ADP and ATP increased eNOS activity, as measured using the l-[3H]arginine-[3H]citrulline assay (Fig. 2A). To characterize the receptor subtype that mediates ADP signaling to eNOS, BAEC were pretreated with the P2Y1-selective antagonist MRS 2179 before the addition of ADP or ATP (37). As shown in Fig. 2, B and C, MRS 2179 inhibited ADP- but not ATP-mediated phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 and AMPK, as well as dephosphorylation of eNOS Ser116. Furthermore, there was no effect of MRS 2179 on ATP-stimulated eNOS activation, whereas P2Y1 antagonism with MRS 2179 effectively blocked ADP-promoted eNOS activation (p < 0.05, n = 3) with an IC50 of ∼2 μm (Fig. 2D). We also found that these ADP responses were unaffected by pertussis toxin (data not shown), a finding consistent with prior reports that have shown that ADP signaling in the vascular wall is pertussis toxin-insensitive (38). To provide additional independent evidence for the involvement of P2Y1 in the ADP response, we designed a duplex siRNA construct targeting the P2Y1 receptor (Fig. 2, E–G). siRNA-mediated knockdown of P2Y1 blocked ADP-promoted eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1179 (Fig. 2F) and Ser635, as well as dephosphorylation at eNOS Ser116. As shown in Fig. 2G, P2Y1 siRNA inhibited the ability of ADP to increase eNOS activity (p < 0.05, n = 3). However, knockdown of P2Y1 had no effect on the phosphorylation or activation of eNOS after ATP treatment (Fig. 2, E–G).

FIGURE 2.

Effects of pharmacologic inhibition or siRNA-mediated knockdown of P2Y1 on ADP-modulated eNOS phosphorylation and activity. A, BAEC were assayed for eNOS enzyme activity by incubating the cells with l-[3H]arginine followed by treatments with nucleotides (50 μm for 20 min) as shown; the eNOS inhibitor nitro-l-arginine (NNA; 30 μm for 20 min) was added where indicated. Cell extracts were processed and analyzed by ion exchange chromatography to quantitate eNOS enzyme activity by measuring levels of l-[3H]citrulline, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Shown here are the mean values ± S.E. of four to six independent experiments. B, lysates from BAEC were prepared from cells that had been incubated with the indicated concentrations of the P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS 2179 or its vehicle for 30 min and then treated with 50 μm ADP (left panel) or ATP (right panel) for 5 min. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed using antibodies directed against phospho-eNOS Ser1179, phospho-eNOS Ser116, and phospho-AMPK. Equal loading was confirmed by immunoblotting with anti-eNOS and anti-AMPK antibodies. The experiments shown are representative of three independent experiments with equivalent results. C, digital chemiluminescence was used to quantitate the relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 in cells preincubated with various concentrations of MRS 2179 and then treated with 50 μm ADP or ATP for 5 min. D, measurement of eNOS enzyme activity using the l-[3H]arginine-[3H]citrulline assay in BAEC incubated with the indicated concentrations of MRS 2179 and then treated with 50 μm ADP, 50 μm ATP, or 30 μm nitro-l-arginine plus agonist for 20 min. Each bar in the graph represents the mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. * indicates p < 0.05 compared with vehicle-treated cells. E, BAEC transfected with control or P2Y1 siRNA were stimulated with 50 μm ADP or ATP for 5 min. Cells were lysed, and phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179, eNOS Ser635, eNOS Ser116, and AMPK was analyzed using immunoblots probed with phosphospecific antibodies directed against specific phosphorylated sites in these proteins. Cell lysates were also probed for total eNOS and AMPK as loading controls. F, analysis of pooled data quantitating the phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 from three to five independent experiments yielding similar results is shown. * indicates p < 0.05. G, BAEC transfected with control or P2Y1 siRNA were treated with ADP (50 μm) or vehicle for 20 min, and eNOS activity was quantitated using the l-[3H]arginine-[3H]citrulline assay. Mean values ± S.E. of four independent experiments are shown with *** indicating p < 0.001. p, phospho; NS, not significant.

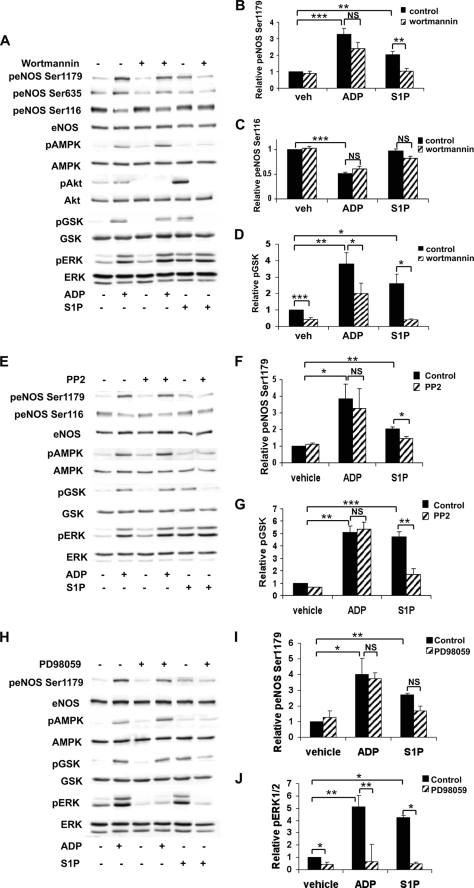

Effects of Inhibition of PI3K/Akt, Src Tyrosine Kinase, and MEK on ADP Signaling in Endothelial Cells

Multiple protein kinases have been shown to be involved in the regulation of eNOS, including protein kinase Akt (14), Src tyrosine kinase (39), and MAPK (21) among others. We therefore used a series of pharmacological inhibitors to systematically assess the potential contribution of each of these pathways to ADP responses in endothelial cells. S1P, a sphingolipid that potently activates eNOS via a G protein-coupled receptor, was used in these pharmacologic studies as a positive control. BAEC were stimulated with agonists after pretreatment with each of the following inhibitors: wortmannin (PI3K inhibitor), PP2 (Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor), and PD98059 (MAPK kinase inhibitor). We found that both wortmannin and PP2 significantly blocked S1P-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (Fig. 3, A, B, E, and F) and GSK3β (Fig. 3, D and G). Despite the marked inhibition of ADP-mediated GSK3β phosphorylation following wortmannin treatment (Fig. 3D), wortmannin did not affect ADP-promoted changes in eNOS phosphorylation (Fig. 3, B and C). Similarly, PD98059 treatment inhibited basal as well as ADP- and S1P-modulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 3, H and J) but failed to significantly alter eNOS phosphorylation responses to these agonists (Fig. 3I). Taken together, these data suggested that PI3K/Akt, Src, and MAPK pathways are not importantly involved in mediating ADP-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS and led us to additional experiments to explore the pathways connecting ADP and eNOS modulation.

FIGURE 3.

Differential effects of pharmacologic inhibition of PI3K/Akt, Src tyrosine kinase, and ERK1/2 pathways on ADP- and S1P-mediated phosphorylation responses in endothelial cells. A, lysates from BAEC were prepared from cells pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin (500 nm) for 30 min and then treated with ADP (50 μm) or S1P (100 nm) for 5 min. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with the antibodies indicated. Shown is an immunoblot representative of five individual experiments that yielded equivalent results. Quantitative analysis using digital chemiluminescence shows the relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (B), eNOS Ser116 (C), and GSK3β (D). E, cells were pretreated with PP2 (10 μm) for 30 min and then stimulated with ADP (50 μm) or S1P (100 nm) for 5 min. This panel shows an immunoblot that is representative of results obtained from three independent experiments. F and G show the quantitation of pooled data presenting the relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 and GSK3β, respectively. H, cells were preincubated for 30 min with PD98059 (50 μm) and then treated for 5 min with ADP (50 μm) or S1P (100 nm). Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and a representative immunoblot probed with the indicated antibodies is shown. This experiment was repeated three times with equivalent results. Relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (I) and ERK1/2 (J) determined by quantitative chemiluminescence, analyzing pooled data from three experiments, is shown. The bars in each graph in this figure represent mean values ± S.E. with * indicating p < 0.05, ** indicating p < 0.01, and *** indicating p < 0.001. p, phospho; veh, vehicle; NS, not significant.

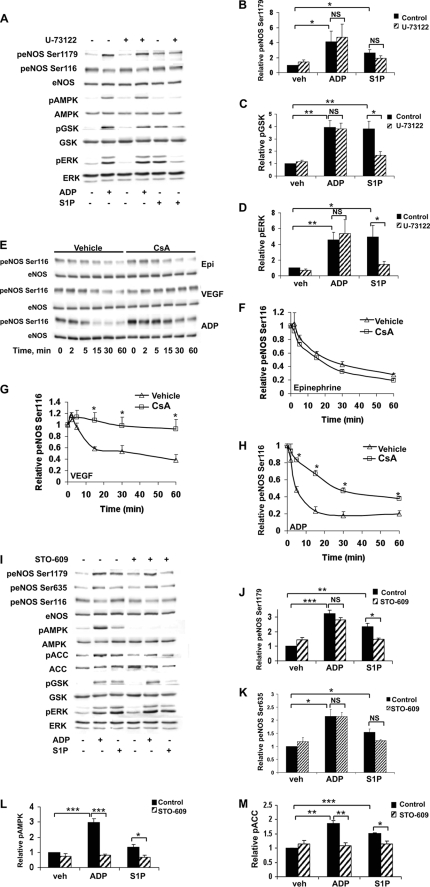

Pharmacologic Investigation of Phospholipid- and Calcium-associated Pathways in Endothelial Responses to ADP

The next series of studies investigated phospholipid- and calcium-associated pathways that have previously been shown to be involved in eNOS signaling. Pretreatment of cells with U-73122, a PLC inhibitor, did not alter eNOS phosphorylation induced by ADP or S1P (Fig. 4, A and B) but did differentially block only S1P-mediated GSK3β and ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 4, C and D). A recent study has suggested that extracellular nucleotides signal to eNOS via the δ isoform of protein kinase C (PKCδ) (8). We therefore used a specific PKCδ inhibitor, rottlerin, to test the role of this PKC isoform in ADP signaling in BAEC. However, there was no effect of rottlerin on eNOS phosphorylation after ADP treatment (data not shown), in contrast to the earlier findings that demonstrated inhibition of ATP responses by rottlerin. We next examined whether calcineurin, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase that is inhibited by cyclosporine A (CsA), is involved in endothelial responses to ADP (Fig. 4, E–H). Previous work in our laboratory has investigated the effects of CsA on inhibition of eNOS dephosphorylation at Ser116 (40). Here we found that CsA did not affect dephosphorylation of eNOS Ser116 in response to epinephrine (Fig. 4F), whereas CsA treatment significantly blocked the effects of VEGF (Fig. 4G) and ADP (Fig. 4H) on eNOS Ser116 dephosphorylation. We continued our pharmacologic examination of potential calcium-associated regulators of eNOS by exploring the effects of the CaMKKβ inhibitor STO-609 (Fig. 4, I–M). ADP- and S1P-promoted phosphorylation of AMPK and its downstream substrate, ACC, was almost completely inhibited by pretreatment with STO-609 (Fig. 4, L and M). We also observed a small (but statistically significant) effect of STO-609 on S1P-mediated eNOS Ser1179 phosphorylation (37 ± 3% decrease in phosphorylation compared with vehicle-treated cells, p < 0.05, n = 3). In contrast, inhibition of CaMKKβ using STO-609 failed to show any effect at all on ADP-modulated eNOS phosphorylation (Fig. 4, J and K).

FIGURE 4.

Endothelial responses to ADP and S1P after inhibition of phospholipase C, calcineurin, or CaMKKβ. A, BAEC were treated with the PLC inhibitor U-73122 (10 μm) for 30 min and then stimulated for 5 min with ADP (50 μm) or S1P (100 nm). Immunoblots were probed with antibodies as indicated. Equal loading was confirmed using antibodies directed against total eNOS, AMPK, GSK3β, and ERK1/2. Shown is a representative immunoblot from four individual experiments that yielded similar results. Quantitative analysis of pooled data is shown for the relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (B), GSK3β (C), and ERK1/2 (D). E, cell lysates were prepared from BAEC pretreated for 30 min with cyclosporine (100 nm) and then stimulated for the times indicated with epinephrine (1 μm), VEGF (20 ng/ml), or ADP (50 μm). Lysates from BAEC were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed using antibodies directed against phospho-eNOS Ser116 and eNOS. Shown here is an immunoblot representing three individual experiments with equivalent results. Analysis of pooled data quantitating relative eNOS Ser116 phosphorylation after treatment with epinephrine, VEGF, or ADP is shown in F–H, respectively. * indicates p < 0.05 compared with agonist-mediated levels of eNOS Ser116 phosphorylation in the absence of cyclosporine. I, BAEC were incubated with STO-609 (10 μm) for 30 min and then treated with ADP (50 μm) or S1P (100 nm) for 5 min. Shown is a representative immunoblot from three individual experiments with similar results. Pooled quantitative data comparing relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (J), eNOS Ser635 (K), AMPK (L), and ACC (M) are shown. Each bar in the graph represents the mean value ± S.E. * denotes p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, and *** denotes p < 0.001. p, phospho; veh, vehicle; NS, not significant; Epi, epinephrine.

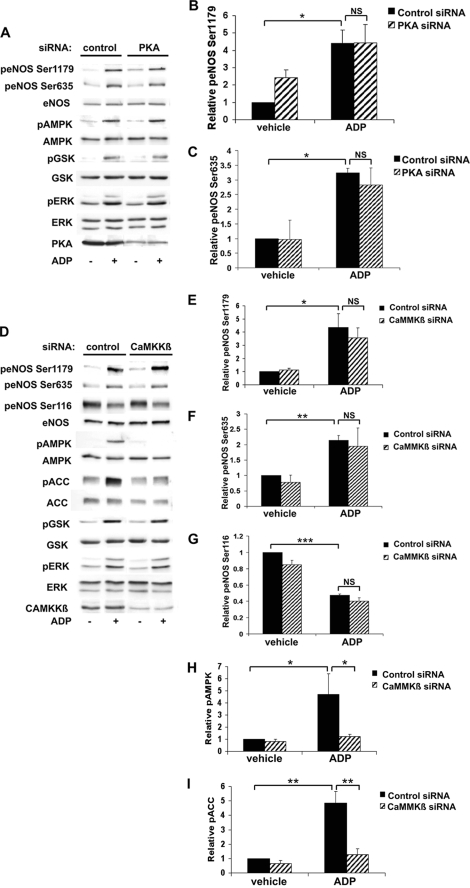

Effects of siRNA-mediated Knockdown of PKA and CaMKKβ on ADP Signaling in Endothelial Cells

We next used siRNA approaches to investigate ADP signaling to eNOS and began by examining the PKA and CaMKKβ pathways, both of which have been implicated in eNOS regulation (16, 22). BAEC were transfected with previously characterized siRNA targeting PKA (31) and then treated with vehicle or ADP. PKA siRNA transfection resulted in ∼90% knockdown of PKA expression, as shown in Fig. 5A. We saw no effect of siRNA-mediated PKA knockdown on ADP-promoted phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 or Ser635 (Fig. 5, A–C). We next transfected BAEC with control or CaMKKβ siRNA prior to treatment with vehicle or ADP and verified efficient knockdown of the target protein (Fig. 5D). Again, there was no alteration of ADP-dependent eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1179, Ser635, or Ser116 following siRNA-mediated CaMKKβ knockdown (Fig. 5, E–G). Importantly, cells transfected with CaMKKβ siRNA demonstrated almost no phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 5H) and ACC (Fig. 5I) after ADP treatment. These data suggest that neither PKA nor CaMKKβ is involved in regulation of ADP-mediated eNOS phosphorylation responses in endothelial cells.

FIGURE 5.

Effects of siRNA-mediated knockdown of PKA and CaMKKβ on ADP signaling in endothelial cells. A, 48 h after BAEC were transfected with control or PKA siRNA, cells were treated with 50 μm ADP for 5 min. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblots were probed using the indicated antibodies. Equal loading was confirmed by probing for total eNOS, AMPK, GSK3β, and ERK1/2. siRNA-mediated knockdown was determined by probing with antibodies for total PKA. Shown is an immunoblot representative of three individual experiments that yielded equivalent results. B and C show quantitative analysis of pooled data for relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 and eNOS Ser635, respectively. D, lysates were prepared from cells transfected with control or CaMKKβ siRNA and then treated for 5 min with ADP (50 μm). A representative immunoblot is shown here with knockdown confirmed by probing for total CaMKKβ. Quantitation of relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (E), eNOS Ser635 (F), eNOS Ser116 (G), AMPK (H), and ACC (I) was assessed using digital chemiluminescence analysis of pooled data. Each bar in the graph represents the mean value ± S.E. of four independent experiments that yielded similar results. * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, and *** denotes p < 0.001. p, phospho; NS, not significant.

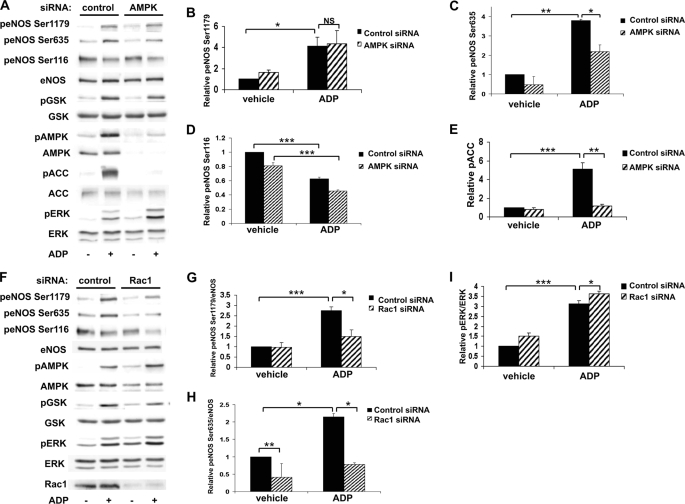

siRNA-mediated Knockdown of AMPK and Rac1 Alters ADP-dependent eNOS Phosphorylation in BAEC

We investigated the role of AMPK and Rac1 in ADP-dependent endothelial responses: these signaling proteins have been previously implicated in receptor-dependent eNOS regulation (15, 25). Cells were transfected with control siRNA or with a previously characterized duplex siRNA construct targeting AMPK and then treated with vehicle or ADP (Fig. 6A). ADP-modulated eNOS phosphorylations at Ser1179 (Fig. 6B) and Ser116 (Fig. 6D) were not affected by AMPK knockdown. However, eNOS phosphorylation at Ser635 after ADP treatment (Fig. 6C) was significantly inhibited following siRNA-mediated AMPK knockdown (p < 0.05, n = 4). As expected, siRNA-mediated AMPK knockdown led to a marked attenuation in the phosphorylation of its substrate, ACC (Fig. 6E). We next explored the consequences of siRNA-mediated knockdown of the small GTPase Rac1. Rac1 has been shown to not only regulate eNOS (25) but also mediate downstream effects of AMPK (30, 41). siRNA-mediated knockdown of Rac1 significantly blocked ADP-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (Fig. 6G) and Ser635 (Fig. 6H), whereas ADP-stimulated phosphorylation of ERK1/2 was not attenuated (Fig. 6I). These data suggest that both AMPK and Rac1 are critical determinants of ADP signaling to eNOS in endothelial cells.

FIGURE 6.

siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK or Rac1 and ADP-modulated eNOS phosphorylation. A, BAEC were transfected with control or AMPK siRNA, and 48 h later, cells were treated for 5 min with ADP (50 μm) or vehicle control. Lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblots were analyzed by probing with the indicated antibodies. Equal loading was determined by probing for total eNOS, GSK3β, ACC, and ERK1/2, and AMPK knockdown was confirmed by probing for total AMPK. This blot is representative of four individual experiments that yielded equivalent results. Quantitative analysis of pooled data comparing relative eNOS Ser1179, eNOS Ser635, eNOS Ser116, and ACC phosphorylation is shown in B–E, respectively. F shows a representative immunoblot of lysates from BAEC prepared from cells transfected with control or Rac1 siRNA prior to ADP treatment (50 μm, 5 min). Protein knockdown was determined using an antibody directed against Rac1. The graphs to the right were obtained by quantitative digital chemiluminescence analysis of pooled data and represent relative phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (G), eNOS Ser635 (H), and ERK1/2 (I), normalized to total eNOS or ERK where appropriate. These data are the result of four independent experiments that yielded similar results. * indicates p < 0.05, ** denotes p < 0.01, and *** represents p < 0.001. p, phospho; NS, not significant.

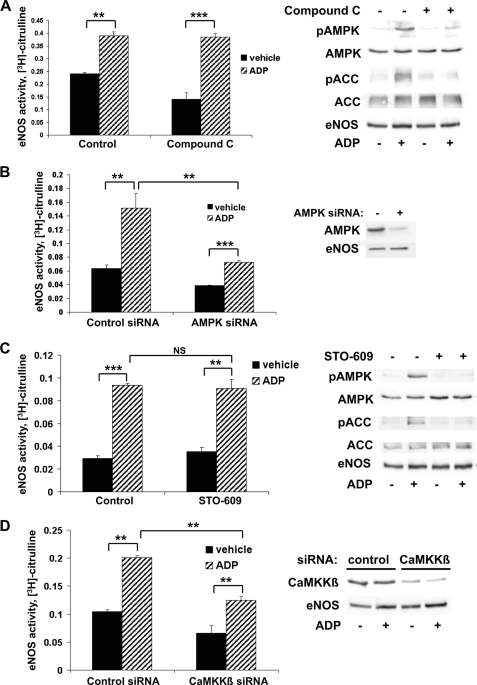

ADP-dependent eNOS Activation Requires the Expression but Not Kinase Activity of AMPK and CaMKKβ

We were intrigued by the lack of effect of CaMKKβ siRNA on ADP-promoted eNOS phosphorylation. The failure of siRNA-mediated CaMKKβ knockdown to affect ADP modulation of eNOS phosphorylation stands in contrast to the clear inhibition of eNOS Ser635 phosphorylation that was seen following siRNA-mediated AMPK knockdown, an unexpected observation considering that AMPK activity is effectively suppressed in both contexts, as confirmed by the suppression of ACC phosphorylation (Figs. 5, D–I, and 6, A–E). Thus, we decided to investigate whether alterations in the phosphorylation state of eNOS might correlate with corresponding changes in eNOS activity. BAEC were pretreated with compound C, a potent and specific inhibitor of AMPK enzyme activity (42), and then treated with vehicle or ADP (Fig. 7A). eNOS activity was measured using the l-[3H]arginine-[3H]citrulline assay as described. Effective blockade of AMPK activity with compound C was confirmed by Western blot analysis showing complete inhibition of phosphorylation of both AMPK and its downstream substrate, ACC (Fig. 7A, right panel). We were therefore surprised to find that treatment of endothelial cells with compound C failed to block ADP-induced eNOS activation (Fig. 7A, left panel). We repeated this experiment using AMPK siRNA (Fig. 7B). As shown in the left panel, siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK attenuated the ADP-promoted increase in eNOS activity (p < 0.01, n = 5); effective siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK expression was confirmed by immunoblot analysis (Fig. 7B, right panel). We then explored the effects of the CaMKKβ inhibitor STO-609 on eNOS enzyme activity (Fig. 7C). We found that ADP-stimulated eNOS activity was totally unaffected by blockade of CaMKKβ kinase activity (Fig. 7C, left panel), whereas STO-609 completely inhibited ADP-dependent phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC (Fig. 7C, right panel), thereby showing effective inhibition of these kinases by STO-609. In Fig. 7D, cells were transfected with control or CaMKKβ siRNA and then treated with vehicle or ADP. ADP-promoted eNOS activity was significantly inhibited by CaMKKβ siRNA (p < 0.01, n = 3). Thus, ADP signaling to eNOS appears to be maintained when the activities of either AMP or CaMKKβ are inhibited (by compound C or STO-609, respectively), but when the expression of these kinases is suppressed by siRNA-mediated targeting, ADP signaling to eNOS is blocked.

FIGURE 7.

Differential effects on ADP-mediated responses of siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK or CaMKKβ versus inhibition of kinase activity. A, BAEC were treated for 30 min with the AMPK inhibitor compound C (20 μm), and eNOS enzyme activity (left panel) was assayed using the l-[3H]arginine-[3H]citrulline assay following the addition of ADP (50 μm) for 20 min. Cell extracts were processed to quantitate formation of l-[3H]citrulline, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Shown here are data from three separate experiments that yielded similar results. The right panel shows data from cells treated with compound C (20 μm, 30 min) prior to ADP stimulation (50 μm, 5 min). This experiment was performed at the same time as the eNOS activity assay was being determined in cells from the same passage. Cell lysates were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and the immunoblot was probed with antibodies against phospho-AMPK and phospho-ACC. Equal loading was determined in immunoblots probed with antibodies against AMPK, ACC, and eNOS, as shown. B, BAEC were transfected with control or AMPK siRNA and treated with 50 μm ADP for 20 min. The left panel shows quantitation of eNOS activity data pooled from three different experiments that yielded equivalent results. siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK was determined by immunoblot analysis (right panel) of cells harvested at the time of the eNOS activity assay. C, BAEC were preincubated with the CaMKKβ inhibitor STO-609 (10 μm) for 30 min and then treated with ADP for 20 min. eNOS enzyme activity is shown on the left with each bar representing the mean value ± S.E. of five independent experiments with similar results. Similar cells were treated with STO-609 (10 μm, 30 min) and then stimulated with ADP (50 μm, 5 min) at the time of eNOS activity measurement. A representative immunoblot probed for phospho-AMPK, AMPK, phospho-ACC, ACC, and eNOS is shown on the right. D, cells were transfected with control or CaMKKβ siRNA, and eNOS activity was measured by quantitating the formation of [3H]citrulline from l-[3H]arginine after adding ADP (50 μm) for 20 min. Shown on the left are the pooled results analyzing data from three independent experiments. Specific CaMKKβ knockdown was confirmed with an immunoblot probed for CaMKKβ and eNOS (right panel). In all graphs, * indicates p < 0.05, ** indicates p < 0.01, and *** represents p < 0.001. p, phospho; NS, not significant.

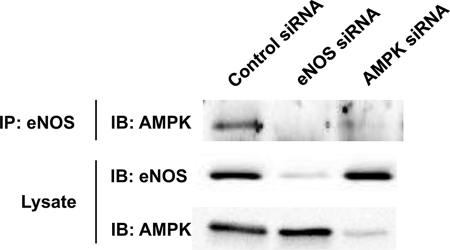

Association of eNOS and AMPK in Endothelial Cells

We further explored the interactions among eNOS, AMPK, and CaMKKβ using co-immunoprecipitation studies in BAEC (Fig. 8). Following immunoprecipitation of eNOS, AMPK was reproducibly detected by immunoblot analysis. As a key control, we showed that siRNA-mediated knockdown of either eNOS or AMPK completely abolished this association. In contrast, siRNA-mediated knockdown of CaMKKβ did not affect co-immunoprecipitation of eNOS and AMPK nor did the AMPK and CaMKKβ kinase inhibitors compound C or STO-609, respectively (data not shown).

FIGURE 8.

Association of eNOS with AMPK in endothelial cells. Shown in this figure are the results of an eNOS-AMPK co-immunoprecipitation experiment in BAEC transfected with control, eNOS, or AMPK siRNA targeting constructs. Immunoprecipitations using eNOS polyclonal antiserum were performed, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Immunoprecipitated complexes were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed in immunoblots using an antibody against AMPK. Cell lysates were also probed in immunoblots probed with anti-eNOS and anti-AMPK antibodies to verify “knockdown” of target proteins. The results shown here are representative of 4–10 independent experiments that yielded similar results. IP, immunoprecipitate; IB, immunoblot.

Rac1 Modulates ADP-induced eNOS Activation and Cell Migration in BAEC

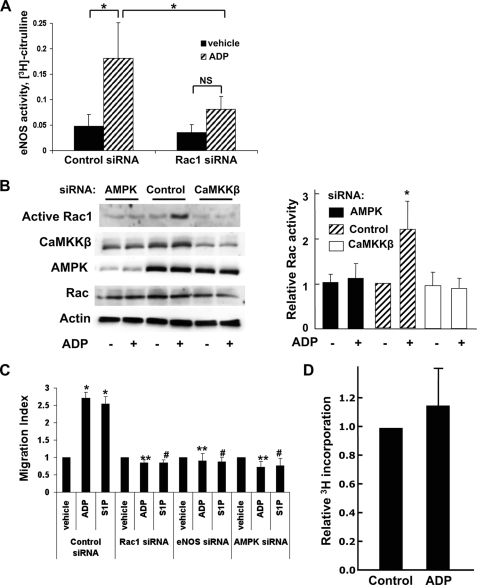

In addition to AMPK and CaMKKβ, these studies identified Rac1 as an important mediator of ADP-dependent eNOS phosphorylation based on our siRNA experiments (Fig. 9). We examined the role of Rac1 in modulating endothelial cell responses to ADP stimulation. We first investigated the effects of Rac1 siRNA on ADP-promoted eNOS activity and found that knockdown of Rac1 inhibited ADP-dependent eNOS activation (p < 0.05, n = 4), as shown in Fig. 9A. Next, we used a pulldown assay to measure active GTP-Rac1 and found that ADP activates Rac1 (Fig. 9B). This activation of Rac by ADP could be inhibited by siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK or CaMKKβ (Fig. 9B). Given the importance of Rac1 in regulation of cell migration and the actin cytoskeleton (23, 24), we explored the effects of ADP on cell migration in BAEC. Cells were transfected with control or specific siRNA targeting Rac1, eNOS, or AMPK and then treated with vehicle, ADP, or S1P. The number of agonist-treated migratory cells/vehicle-treated migratory cells is represented as the migratory index within each siRNA group. As shown in Fig. 9C, both ADP and S1P significantly increased cell migration in control siRNA-transfected cells. However, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Rac1, eNOS, or AMPK abrogated ADP and S1P-promoted cell migration. Finally, although ADP increased endothelial cell migration, addition of ADP did not promote cell proliferation, as measured by incorporation of 3H into cells (Fig. 9D).

FIGURE 9.

Rac1 modulates ADP-modulated eNOS activity and cell migration in endothelial cells. A, cells were transfected with control or Rac1 siRNA, and eNOS activity was assayed by measuring the conversion of l-[3H]arginine to l-[3H]citrulline, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” These pooled data are derived from four separate experiments. Each bar in the graphs represents the mean value ± S.E. * indicates p < 0.05, and ** denotes p < 0.01. B, cells were transfected with control, AMPK, or CaMKKβ siRNA and then treated for 10 min with ADP (50 μm) or vehicle. Rac1 activity was assayed using the GST-PAK pulldown technique. Representative immunoblots probed for Rac1 in cell lysates and following GST-PAK pulldown, AMPK, CaMKKβ, and β-actin are shown on the left. On the right is a quantitative analysis of pooled Rac activity data from four independent experiments with equivalent results. C, BAEC were transfected with duplex siRNA constructs targeting Rac1, eNOS, or AMPK or control siRNA and incubated in a Transwell cell culture chamber. 50 μm ADP or 100 nm S1P was added, and cell migration was analyzed, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The migration index represents the number of migratory cells following siRNA transfection/number of migratory cells determined under basal conditions in control siRNA-transfected BAEC. Each bar in the graph represents the mean ± S.E. from four independent experiments. * indicates p < 0.001 compared with vehicle-treated control siRNA-transfected BAEC, ** indicates p < 0.001 compared with ADP-treated control siRNA-transfected BAEC, and # indicates p < 0.001 compared with S1P-treated control siRNA-transfected BAEC. D, BAEC were seeded onto 24-well plates, treated overnight with 50 μm ADP or vehicle, and labeled with [3H]thymidine, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Cell proliferation was assayed by measuring incorporation of [3H]thymidine. Shown here is the pooled data from two independent sets of experiments, each performed in triplicate.

DISCUSSION

These studies explored the signaling pathways whereby ADP modulates eNOS in vascular endothelial cells. ADP and other purine nucleotides regulate diverse responses in both vascular smooth muscle and endothelial cells and can modulate short term changes in vascular tone as well as longer term trophic processes, such as cell migration and proliferation (4, 6, 10, 43). Previous investigations have focused on the roles of ATP and UTP in the vasculature and have shown that the specific vascular response elicited depends on the nature and cellular source of the nucleotide agonist, the specific target cell, and the receptor subtype (4). In contrast to these prior studies of ATP and UTP, ADP has been examined mainly in the context of platelet biology. Indeed, ADP signaling pathways in platelets have been extensively characterized, resulting in the development of widely used ADP receptor antagonists such as clopidogrel. ADP has previously been found to activate AMPK in a CaMKKβ-dependent manner (44). ADP can activate eNOS, leading to endothelium-dependent arterial relaxation, and can promote endothelial cell migration via MAPK pathways (10, 45, 46). However, the mechanisms by which ADP exerts its vasoactive and trophic effects on endothelial cells remain less well understood, and mechanistic links between AMPK, CaMKKβ, and eNOS in this context have not been established. In the present studies, we explored endothelial responses to ADP and identified Rac1 and specifically the expression, but not kinase activities, of AMPK and CaMKKβ as key mediators of ADP signaling to eNOS.

We found that ADP promoted the reversible phosphorylation of multiple signaling proteins in vascular endothelial cells. As shown in Fig. 1, ADP treatment of BAEC resulted in the phosphorylation of eNOS at two of the phosphoserine residues associated with eNOS activation, Ser1179 and Ser635. Stimulation of ADP also promoted the reversible phosphorylation of AMPK at its activation site, Thr172, and resulted in the reversible phosphorylation of kinases Akt, GSK3β, and ERK1/2. All of these responses were dose- and time-dependent with an EC50 of ∼15 μm, a concentration that is within the physiologic range of ADP levels in blood (35, 36). We additionally found that ADP promoted the dephosphorylation of eNOS at Ser116 (Fig. 1, B and E), as has been previously reported for a subset of eNOS agonists, including epinephrine (31) and VEGF (40). Phosphorylation of the eNOS Ser116 site leads to enzyme inhibition (47). Unlike the other more rapid ADP-dependent phosphorylation responses studied here, eNOS Ser116 dephosphorylation persisted throughout the 40-min time course, suggesting that dephosphorylation at this site may represent a longer term regulatory mechanism for eNOS. These data show that ADP treatment promotes reversible phosphorylation responses in multiple endothelial signaling proteins and elicits both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of eNOS at several residues, consistent with activation of the enzyme. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 2A, ADP promoted a striking increase in eNOS enzyme activity in endothelial cells.

We next explored the purinergic receptor subtype that modulates ADP signaling responses in endothelial cells (Fig. 2). Many studies of purinergic pathways in the vessel wall have focused on ATP, yet ADP represents an important extracellular signaling molecule that can exert independent effects quite distinct from those responses elicited by ATP. Indeed, endothelial cell purinergic receptor subtypes have preferential affinities for different nucleotides: the P2X class of receptors responds only to ATP (1), and P2Y2 receptors respond to both ATP and UTP, whereas P2Y1 receptors preferentially bind ADP as a ligand (4). Importantly, ectonucleotidases located on the surface of endothelial cells are responsible for converting ATP to ADP (4). However, because platelet dense granule concentrations of ATP + ADP are in the 100 mm range (2), a concerted release of ADP from activated platelets near the endothelium could potentially overwhelm ectonucleotidase enzymes and lead to ADP-initiated signaling in endothelial cells. A recent study has shown that ATP can promote the phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 and activate eNOS (8). In the present studies, we showed that both ADP and ATP activate eNOS, as measured with the l-[3H]arginine-[3H]citrulline assay (Fig. 2A). Moreover, both ADP and ATP promoted the phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 and of AMPK, as well as dephosphorylation of eNOS Ser116 (Fig. 2B). Importantly, we observed that the P2Y1-selective receptor antagonist MRS 2179 significantly inhibited ADP- but not ATP-modulated eNOS phosphorylation and activation (Fig. 2, B–D). Similarly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of the P2Y1 receptor completely blocked ADP signaling responses (Fig. 2, E–G), whereas pertussis toxin had no effect. In contrast, previous studies have shown that ATP-dependent receptor-mediated signaling is pertussis toxin-sensitive (48). Taken together, these findings establish that ADP and ATP are separate agonists that activate distinct receptors and provide evidence that P2Y1 is the critical receptor mediating ADP signaling to eNOS in endothelial cells.

We performed a systematic investigation of signaling pathways associated with eNOS regulation to explore the potential involvement of these pathways in ADP responses in endothelial cells. We decided to compare and contrast ADP responses with the signaling pathways modulated by S1P, an extensively characterized eNOS agonist that activates its cognate G protein-coupled receptor in these cells. We used a panel of pharmacological inhibitors to explore endothelial signaling responses to ADP and S1P. Fig. 3, A–D, shows experiments using the PI3K inhibitor wortmannin to probe ADP responses in endothelial cells. The role of PI3K/Akt in eNOS regulation has been extensively studied (14, 49), and prior work in our laboratory has shown that eNOS can be regulated by S1P via an AMPK → Rac1 → Akt → eNOS pathway (30). In the present study, we found that ADP promoted the phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 2E), and we hypothesized that ADP might signal to eNOS Ser1179 in a PI3K/Akt-dependent manner. As expected, inhibition of the PI3K/Akt pathway by wortmannin blocked ADP- and S1P-promoted phosphorylation of GSK3β (a downstream target of Akt) and also attenuated S1P-mediated eNOS Ser1179 phosphorylation (Fig. 3, A, B, and D). However, wortmannin failed to inhibit ADP-mediated alterations in eNOS phosphorylation (Fig. 3, A–C), suggesting that ADP signals to eNOS in BAEC through a PI3K/Akt-independent pathway. The suppression by wortmannin of ADP- or S1P-mediated phosphorylation of the Akt substrate GSK3β served as a positive control (Fig. 3D); the failure of wortmannin to attenuate agonist-modulated ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A) helped to establish specificity of the effect seen. Other kinase inhibitors also revealed important differences between ADP and S1P responses in these cells. We have previously reported that S1P-mediated eNOS Ser1179 phosphorylation is completely inhibited by the Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor PP2 (25, 31). Similar to the effects of wortmannin, we found that PP2 differentially affected ADP and S1P signaling: the ADP response was entirely unaltered by PP2, whereas PP2 treatment completely blocked S1P-mediated phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 and GSK3β (Fig. 3, E–G). We next explored ADP modulation of ERK1/2, another kinase known to regulate eNOS (21), and found that the MEK inhibitor PD98059 had no effect on either ADP or S1P modulation of eNOS Ser1179 phosphorylation (Fig. 3, H–J). The dramatic decreases in basal and agonist-stimulated levels of phospho-ERK1/2 seen after PD98059 treatment served as a key positive control for the effects of this kinase inhibitor (Fig. 3J). Thus, although ADP promoted the robust phosphorylation of protein substrates for the kinases Akt, MEK, and Src, the failure of these kinase inhibitors to attenuate ADP signaling to eNOS (along with appropriate positive experimental controls) suggests that ADP signaling to eNOS is independent of these kinase pathways. In addition, we found that the PLC inhibitor U-73122 attenuated S1P-mediated phosphorylation responses but had no effect on responses to ADP (Fig. 4, A–D). We were slightly surprised by this finding, as PLC has been implicated in other agonist-mediated signaling pathways to eNOS (17). A recent study has suggested that purinergic signaling to eNOS in endothelial cells is mediated by the PKCδ (8). To examine the potential role of PKCδ more closely, we treated cells with rottlerin, an inhibitor specific for PKCδ. In contrast to a recent report (8), we did not find any effect of rottlerin on ADP signaling. This difference may be reconciled by the fact that these previous studies using rottlerin investigated ATP and UTP signaling responses, whereas our studies focused on ADP. As shown and discussed above (Fig. 2), we demonstrated that ADP and ATP are distinct agonists that signal to eNOS through different receptors. Taken together, our studies using protein kinase inhibitors identified PI3K, Src tyrosine kinase, and PLC as points of differential regulation of eNOS by ADP versus S1P in endothelial cells.

Although it is clear that protein kinases play key roles in eNOS regulation, eNOS is also dynamically modulated by protein phosphatase pathways. The protein phosphatases involved in eNOS regulation remain less completely understood, but several eNOS agonists have been shown to promote eNOS dephosphorylation. For example, the potent eNOS agonist VEGF has been shown to activate calcineurin, a calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase (50). Previous work in our laboratory showed that dephosphorylation of eNOS Ser116 after VEGF treatment can be blocked by the calcineurin inhibitor CsA (40). In the present study, we demonstrated that CsA could additionally inhibit ADP- but not epinephrine-promoted dephosphorylation of eNOS Ser116 (Fig. 4, E–H). Although this observation does not establish that calcineurin directly dephosphorylates eNOS, these findings do indicate that calcineurin-modulated pathways are involved in regulation of eNOS dephosphorylation in response to ADP and VEGF but not epinephrine.

Given the critical role of CaMKKβ in AMPK-dependent eNOS regulation (22, 51), we evaluated the role of CaMKKβ in ADP-mediated eNOS phosphorylation using the specific pharmacologic inhibitor STO-609 (Fig. 4, I–M). AMPK can be phosphorylated by several upstream kinases, including CaMKKβ, LKB1, and transforming growth factor-β-activated kinase (52). STO-609 completely blocked ADP-mediated phosphorylation of AMPK (Fig. 4L) and ACC (Fig. 4M), indicating that CaMKKβ is the key upstream AMPK kinase relevant to ADP signaling in BAEC. However, despite the effective inhibition of CaMKKβ kinase activity established by these multiple positive controls, STO-609 had no effect at all on ADP-modulated eNOS phosphorylation (Fig. 4, I–K). In contrast, Fig. 4J shows that S1P-mediated eNOS Ser1179 phosphorylation was significantly blocked by CaMKKβ inhibition, consistent with our prior findings (30). Taken together, these studies suggest that the kinase activity of CaMKKβ is not necessary for ADP-promoted eNOS phosphorylation and identify differential roles for CaMKKβ in ADP versus S1P signaling to eNOS.

As shown in Fig. 5, H and I, studies using siRNA-mediated CaMKKβ knockdown yielded results similar to those from our experiments examining the CaMKKβ inhibitor STO-609: both pharmacological and siRNA approaches indicated that that CaMKKβ is the upstream kinase responsible for ADP-promoted phosphorylation and activation of AMPK. Importantly, siRNA-mediated knockdown of CaMKKβ did not significantly alter eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1179, Ser635, or Ser116 (Fig. 5, D–G), further supporting the hypothesis that ADP-dependent eNOS phosphorylation is independent of the kinase activity of CaMKKβ or AMPK. Prior studies have established that phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr172 is necessary for full AMPK activation (52), and our findings document that this phosphorylation response was completely blocked by CaMKKβ siRNA (Fig. 5H). Thus, CaMKKβ knockdown abolished not only CaMKKβ kinase activity but also the kinase activity of AMPK. Based on these observations, we expected that siRNA-mediated AMPK knockdown would show results similar, if not identical, to those seen following siRNA-mediated knockdown of CaMKKβ. As shown in Fig. 6, A and E, siRNA-mediated AMPK knockdown attenuated the phosphorylation of its downstream target, ACC. Although no changes in phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 (Fig. 6B) and Ser116 (Fig. 6D) were observed, we noted a significant decrease in eNOS Ser635 phosphorylation (Fig. 6C) associated with the decrease in AMPK abundance following siRNA-mediated AMPK knockdown, an effect that was not seen after inhibition of AMPK enzyme activity using STO-609. The striking discrepancy between the marked consequence of siRNA-mediated AMPK knockdown and the lack of an effect of CaMKKβ siRNA on eNOS phosphorylation, in both contexts associated with the complete suppression of AMPK activity, suggested that it is the expression of AMPK protein, and not its kinase activity, that is the key determinant of ADP-dependent eNOS phosphorylation.

To further explore this surprising observation and to examine whether these changes in eNOS phosphorylation resulted in any functional consequences, we assessed the effects of AMPK and CaMKKβ kinase activity inhibition and the consequences of siRNA-mediated knockdown of protein expression on ADP-dependent eNOS activation. As shown in Fig. 7A, we found that the AMPK enzyme inhibitor compound C effectively blocked phosphorylation of AMPK and ACC but failed to alter ADP-induced eNOS activation. In contrast, knockdown of AMPK using siRNA clearly inhibited eNOS activity after ADP stimulation (Fig. 7B). We found similar results in our studies with CaMKKβ: inhibition of kinase activity with STO-609 blocked AMPK activation but failed to affect ADP-promoted eNOS activation (Fig. 7C), whereas siRNA-mediated knockdown of CaMKKβ significantly inhibited eNOS activity following ADP treatment (Fig. 7D). We were surprised to discover that blockade of AMPK and CaMKKβ kinase activities by two highly specific pharmacologic kinase inhibitors (compound C and STO-609, respectively) had no effect whatsoever on ADP-stimulated eNOS activation, yet siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK and CaMKKβ significantly decreased eNOS activity. A number of possible explanations could account for these apparently paradoxical findings. It should be noted that the siRNAs used in these studies have been extensively validated in prior publications without detection of any discernible off-target effects. Although phosphorylation of the AMPK α subunit at Thr172 is the main activation site required for full AMPK activity, other sites of AMPK phosphorylation have been identified (53, 54). It has been suggested that some of these other AMPK phosphorylation sites are not involved in AMPK activation (53). However, a more recent study has shown that one of these sites in AMPK can be phosphorylated by PKA and through an autophosphorylation mechanism (54). Our studies documented that compound C and STO-609 effectively abrogate phosphorylation of AMPK at Thr172, but it remains to be determined whether ADP modulates AMPK phosphorylation at these additional sites. It is formally possible that these other sites could also regulate AMPK and allow for residual AMPK activity after compound C or STO-609 treatment, thus accounting for the observed persistence of eNOS activation by ADP following kinase inhibition. However, this explanation seems unlikely given the total disappearance of ACC phosphorylation following AMPK inhibition with compound C and STO-609 (Fig. 7, A and C, right panels), confirming effective inhibition of AMPK kinase activity following treatment with these inhibitors.

We instead favor a different hypothesis in which protein expression, rather than the kinase activity, of AMPK and CaMKKβ represents the key determinant of ADP signaling to eNOS. There are precedents for such a hypothesis: several other protein kinases have been shown to fulfill signaling roles independent of their kinase activities. For example, a member of the family of dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinases has recently been found to act as a scaffold for an E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (55). Similarly, kinase-independent roles for the p110β isoform of the class I PI3Ks have been shown to be important in insulin signaling and endocytosis (56, 57). Importantly, we documented in endothelial cells an association between AMPK and eNOS that was abolished by siRNA-mediated knockdown of either protein (Fig. 8). Given the decrease in eNOS Ser635 phosphorylation observed after AMPK knockdown, one possible explanation for our results is that AMPK may act to stabilize eNOS in a conformation that leaves the Ser635 site more accessible to other kinases. However, indirect regulatory interactions between AMPK and eNOS are also possible; indeed, there have been prior reports of eNOS-AMPK interactions in other cell types (15, 58). In the present studies (Fig. 8), we found that the eNOS-AMPK co-immunoprecipitation was abrogated by siRNA-mediated knockdown of either AMPK or eNOS, yet this association was not blocked either by kinase inhibitors or by siRNA-mediated CaMKKβ knockdown. The differential effects on ADP-promoted eNOS activation of siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK or CaMKKβ versus inhibition of AMPK or CaMKKβ kinase activity (Fig. 7) suggest that these proteins may function in a kinase-independent manner as part of a signaling complex that connects ADP receptor-mediated signaling to eNOS.

We also investigated the role of Rac1 in ADP regulation of eNOS in endothelial cells. Rac1 is a small GTPase that functions as a molecular switch between inactive, GDP-bound and active, GTP-bound states. In addition to well established roles in cell migration and actin cytoskeleton regulation (23, 24), Rac1 has also been implicated in regulation of eNOS (25). As shown in Fig. 6, G and H, siRNA-mediated knockdown of Rac1 blocked ADP-promoted phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1179 and Ser635 while leaving phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (Fig. 6I) unaffected. We additionally found that ADP activated Rac1 (Fig. 9B) and observed that siRNA-mediated knockdown of Rac1 significantly inhibited ADP-induced eNOS activation (Fig. 9A), indicating for the first time, to our knowledge, an important role for this small G protein in ADP signaling in endothelial cells. Prior studies have implicated a role for Rac1 as a downstream mediator of AMPK-dependent regulation of eNOS in endothelial cells (30, 41), although it appears that Rac1 itself can also regulate AMPK (41). Based on the dramatic inhibition of ADP-promoted Rac activation after siRNA-mediated knockdown of AMPK or CaMKKβ (Fig. 9B), we demonstrate here that Rac1 serves as a downstream mediator of AMPK- and CaMKKβ-dependent eNOS regulation by ADP. In the present studies, we further showed that ADP promoted robust endothelial cell migration to a degree similar to that seen with S1P (Fig. 9C). siRNA-mediated knockdown of Rac1, eNOS, or AMPK, however, abrogated this ADP-promoted cell migration, indicating key roles for these proteins in ADP-modulated endothelial cell migration. The lack of significantly increased incorporation of 3H thymidine into cells after ADP treatment, as shown in Fig. 9D, suggests that ADP increases endothelial cell migration rather than cell proliferation.

In summary, these studies pursued pharmacological approaches and siRNA interference methodologies to examine the mechanisms of ADP signaling in vascular endothelial cells. Our findings demonstrate that ADP elicits multiple phosphorylation responses in endothelial cells, including striking alterations in the phosphorylation state of eNOS, and these experiments show that these responses are dependent on P2Y1 receptor-mediated activation by ADP but not ATP. Although ADP activates many protein kinase pathways previously implicated in eNOS regulation, we found that most of these kinases do not appear to mediate ADP modulation of eNOS. Our findings do, however, establish the critical involvement of Rac1 in ADP-mediated control of NO-dependent pathways and cellular migration in the vascular endothelium. Furthermore, we observed that, although protein expression of AMPK and CaMKKβ was required for ADP signaling to eNOS, their kinase activities did not appear to be necessary. Taken together, these studies identify distinctive features of ADP-dependent signaling pathways in the vascular endothelium and provide new insight into the roles of purine nucleotides in vascular homeostasis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Juliano Sartoretto for assistance and helpful discussions and are indebted to Dr. Gordon H. William and the Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Hypertension Division at Brigham and Women's Hospital for guidance and support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL46457, H48743, and GM36259 (to T. M.) and 5T32HL07609-22 (to C. N. H.).

- eNOS

- endothelial isoform of nitric-oxide synthase

- BAEC

- bovine aortic endothelial cells

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- PI3K

- phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- CaMKKβ

- calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-β

- AMPK

- AMP-activated protein kinase

- PKA

- cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase/protein kinase A

- PKC

- protein kinase C

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- S1P

- sphingosine 1-phosphate

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- GSK3β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3-β

- ACC

- acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- CsA

- cyclosporine A

- PKCδ

- δ isoform of protein kinase C

- NO

- nitric oxide

- MEK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burnstock G. (2007) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 1471–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubyak G. R., el-Moatassim C. (1993) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 265, C577–C606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drury A. N., Szent-Györgyi A. (1929) J. Physiol. 68, 213–237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erlinge D., Burnstock G. (2008) Purinergic Signal. 4, 1–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamamoto K., Sokabe T., Matsumoto T., Yoshimura K., Shibata M., Ohura N., Fukuda T., Sato T., Sekine K., Kato S., Isshiki M., Fujita T., Kobayashi M., Kawamura K., Masuda H., Kamiya A., Ando J. (2006) Nat. Med. 12, 133–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillois X., Chaulet H., Belloc I., Dupuch F., Desgranges C., Gadeau A. P. (2002) Circ. Res. 90, 678–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaczmarek E., Erb L., Koziak K., Jarzyna R., Wink M. R., Guckelberger O., Blusztajn J. K., Trinkaus-Randall V., Weisman G. A., Robson S. C. (2005) Thromb. Haemost. 93, 735–742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.da Silva C. G., Specht A., Wegiel B., Ferran C., Kaczmarek E. (2009) Circulation 119, 871–879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wihlborg A. K., Wang L., Braun O. O., Eyjolfsson A., Gustafsson R., Gudbjartsson T., Erlinge D. (2004) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 1810–1815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen J., DiCorleto P. E. (2008) Circ. Res. 102, 448–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LeRoy E. C., Ager A., Gordon J. L. (1984) J. Clin. Investig. 74, 1003–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dudzinski D. M., Michel T. (2007) Cardiovasc. Res. 75, 247–260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mount P. F., Kemp B. E., Power D. A. (2007) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 42, 271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fulton D., Gratton J. P., McCabe T. J., Fontana J., Fujio Y., Walsh K., Franke T. F., Papapetropoulos A., Sessa W. C. (1999) Nature 399, 597–601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z. P., Mitchelhill K. I., Michell B. J., Stapleton D., Rodriguez-Crespo I., Witters L. A., Power D. A., Ortiz de Montellano P. R., Kemp B. E. (1999) FEBS Lett. 443, 285–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Michell B. J., Chen Z. p., Tiganis T., Stapleton D., Katsis F., Power D. A., Sim A. T., Kemp B. E. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17625–17628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gélinas D. S., Bernatchez P. N., Rollin S., Bazan N. G., Sirois M. G. (2002) Br. J. Pharmacol. 137, 1021–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butt E., Bernhardt M., Smolenski A., Kotsonis P., Fröhlich L. G., Sickmann A., Meyer H. E., Lohmann S. M., Schmidt H. H. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5179–5187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Partovian C., Zhuang Z., Moodie K., Lin M., Ouchi N., Sessa W. C., Walsh K., Simons M. (2005) Circ. Res. 97, 482–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sud N., Wedgwood S., Black S. M. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 294, L582–L591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 21.Cale J. M., Bird I. M. (2006) Biochem. J. 398, 279–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stahmann N., Woods A., Carling D., Heller R. (2006) Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 5933–5945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu Y. L., Li S., Miao H., Tsou T. C., del Pozo M. A., Chien S. (2002) J. Vasc. Res. 39, 465–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waschke J., Drenckhahn D., Adamson R. H., Curry F. E. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 287, H704–H711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gonzalez E., Kou R., Michel T. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 3210–3216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loscalzo J., Welch G. (1995) Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 38, 87–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ziche M., Morbidelli L., Masini E., Amerini S., Granger H. J., Maggi C. A., Geppetti P., Ledda F. (1994) J. Clin. Investig. 94, 2036–2044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Michel T., Li G. K., Busconi L. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 6252–6256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzalez E., Nagiel A., Lin A. J., Golan D. E., Michel T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 40659–40669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine Y. C., Li G. K., Michel T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20351–20364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kou R., Michel T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 32719–32729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kou R., Igarashi J., Michel T. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 4982–4988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Busconi L., Michel T. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 8410–8413 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson L. J., Michel T. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 11776–11780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mills D. C., Robb I. A., Roberts G. C. (1968) J. Physiol. 195, 715–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gordon J. L. (1986) Biochem. J. 233, 309–319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baurand A., Gachet C. (2003) Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 21, 67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shimokawa H., Flavahan N. A., Vanhoutte P. M. (1991) Circulation 83, 652–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haynes M. P., Li L., Sinha D., Russell K. S., Hisamoto K., Baron R., Collinge M., Sessa W. C., Bender J. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2118–2123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kou R., Greif D., Michel T. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29669–29673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kou R., Sartoretto J., Michel T. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14734–14743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim E. K., Miller I., Aja S., Landree L. E., Pinn M., McFadden J., Kuhajda F. P., Moran T. H., Ronnett G. V. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 19970–19976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burnstock G. (2002) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 364–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.da Silva C. G., Jarzyna R., Specht A., Kaczmarek E. (2006) Circ. Res. 98, e39–e47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buvinic S., Briones R., Huidobro-Toro J. P. (2002) Br. J. Pharmacol. 136, 847–856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guns P. J., Korda A., Crauwels H. M., Van Assche T., Robaye B., Boeynaems J. M., Bult H. (2005) Br. J. Pharmacol. 146, 288–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li C., Ruan L., Sood S. G., Papapetropoulos A., Fulton D., Venema R. C. (2007) Vascul. Pharmacol. 47, 257–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang H., Weir B. K., Marton L. S., Lee K. S., Macdonald R. L. (1997) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 30, 767–774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boo Y. C., Sorescu G., Boyd N., Shiojima I., Walsh K., Du J., Jo H. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 3388–3396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Armesilla A. L., Lorenzo E., Gómez del Arco P., Martínez-Martínez S., Alfranca A., Redondo J. M. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 2032–2043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reihill J. A., Ewart M. A., Hardie D. G., Salt I. P. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 354, 1084–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hardie D. G. (2008) FEBS Lett. 582, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Woods A., Vertommen D., Neumann D., Turk R., Bayliss J., Schlattner U., Wallimann T., Carling D, Rider M. H. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28434–28442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hurley R. L., Barré L. K., Wood S. D., Anderson K. A., Kemp B. E., Means A. R., Witters L. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36662–36672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maddika S., Chen J. (2009) Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 409–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jia S., Liu Z., Zhang S., Liu P., Zhang L., Lee S. H., Zhang J., Signoretti S., Loda M., Roberts T. M., Zhao J. J. (2008) Nature 454, 776–779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirsch E., Braccini L., Ciraolo E., Morello F., Perino A. (2009) Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morrow V. A., Foufelle F., Connell J. M., Petrie J. R., Gould G. W., Salt I. P. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31629–31639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]