Abstract

The L-type calcium channel (LTCC) has a variety of physiological roles that are critical for the proper function of many cell types and organs. Recently, a member of the zinc-regulating family of proteins, ZnT-1, was recognized as an endogenous inhibitor of the LTCC, but its mechanism of action has not been elucidated. In the present study, using two-electrode voltage clamp recordings in Xenopus oocytes, we demonstrate that ZnT-1-mediated inhibition of the LTCC critically depends on the presence of the LTCC regulatory β-subunit. Moreover, the ZnT-1-induced inhibition of the LTCC current is also abolished by excess levels of the β-subunit. An interaction between ZnT-1 and the β-subunit, as demonstrated by co-immunoprecipitation and by fluorescence resonance energy transfer, is consistent with this result. Using surface biotinylation and total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in HEK293 cells, we show a ZnT-1-dependent decrease in the surface expression of the pore-forming α1-subunit of the LTCC. Similarly, a decrease in the surface expression of the α1-subunit is observed following up-regulation of the expression of endogenous ZnT-1 in rapidly paced cultured cardiomyocytes. We conclude that ZnT-1-mediated inhibition of the LTCC is mediated through a functional interaction of ZnT-1 with the LTCC β-subunit and that it involves a decrease in the trafficking of the LTCC α1-subunit to the surface membrane.

Introduction

L-type calcium channels (LTCCs4; CaV1 family) play a crucial role in multiple physiological processes, including regulation of cardiac excitability (1), excitation-contraction coupling (2–5), and synaptic vesicle release (6, 7). They also modulate Ca2+ homeostasis, hormone secretion, phosphorylation processes, and gene regulation (8). In addition, alterations in LTCC function have been linked to several pathophysiologies, such as cardiac arrhythmias (1, 9), cardiac hypertrophy and failure (10, 11), abnormal insulin secretion (12), and severe multisystemic congenital abnormalities (13).

LTCCs are hetero-oligomeric proteins consisting of up to four subunits. The channel's putative structure includes the pore-forming α1-subunit along with the accessory α2δ-, β2-, and γ-subunits. The accessory subunits, which are tightly but not covalently bound to the α1-subunit, modulate the biophysical properties of the LTCC, including its voltage dependence, its current amplitude, and its kinetics of activation and inactivation (1, 14–16). Functionally, LTCCs are voltage-dependent channels that are modulated by intracellular calcium, calmodulin, and protein kinases A and C (6, 17–20), to name a few. Until recently, most studies of LTCC function have concentrated on the modulation of its biophysical properties. However, new findings attribute an important role to LTCC surface expression in governing the long term regulation of LTCC activity (21–25). Translocation of the LTCC to the plasma membrane involves the β-subunits, which act as chaperones in guiding the α1-subunit from the endoplasmic reticulum to the surface (26, 27). This mechanism is now known to be regulated by a variety of elements, including voltage, calmodulin, and members of the RGK (Rem, Rad, and Gem/kir) family (21, 23, 25, 28, 29).

Zinc transporter 1 (ZnT-1) was recently identified as an endogenous modulator of LTCC function (30, 31). This transmembrane protein has been investigated mainly in the context of zinc metabolism and has been shown to confer resistance to zinc toxicity (32–36). ZnT-1 is expressed in most tissues, with high levels of expression observed primarily in the brain, the pancreas, the testes, and the heart (37–39). ZnT-1 inhibition of LTCC activity has recently been confirmed in several cell types (30, 31, 40). For example, silencing the expression of endogenous ZnT-1 in neurons was shown to markedly increase Ca2+ influx via the LTCC, thereby enhancing synaptic release (40). Recently, we demonstrated that expression of ZnT-1 is modulated in cardiomyocytes in parallel to documented alterations in LTCC function. We observed that both rapid electrical pacing in rat atria in vivo, as well as in neonatal cardiomyocytes in primary culture, enhanced ZnT-1 expression and reduced Ca2+ influx through LTCCs (31). Furthermore, we showed that the inhibitory effect of rapid pacing on LTCC function was antagonized by silencing the expression of ZnT-1 (31). Analysis of human atrial samples collected during heart surgery revealed increased expression of ZnT-1 in patients suffering from atrial fibrillation as compared with patients in sinus rhythm (31) implying a role for ZnT-1 in the LTCC dysfunction that is believed to play an important role in the pathophysiology of this common arrhythmia (9, 41).

ZnT-1 decreases the current amplitude of LTCCs in Xenopus oocytes without altering the total expression of the Cav1.2 α1-subunit or the steady-state activation or the inactivation kinetics of the LTCC current (31). Attempts to demonstrate an interaction between ZnT-1 and the LTCC α1-subunit were unsuccessful (30).5 Based on these results, we hypothesize that ZnT-1 indirectly antagonizes targeting of the α1-subunit to the plasma membrane. Because the regulatory β-subunit is involved in trafficking of the LTCC to the plasma membrane (26, 27), our present study aimed to determine whether a functional interaction of ZnT-1 with the β-subunit underlies its inhibitory effect. Indeed, we demonstrate here that ZnT-1 cannot inhibit the LTCC current in the absence of the β-subunit. Furthermore, overexpression of the β-subunit blocks the inhibitory effect of ZnT-1 on LTCC activity, consistent with a stoichiometric balance between ZnT-1 and the β-subunit. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements confirm an interaction between ZnT-1 and the β-subunit, as predicted by our hypothesis. Finally, surface biotinylation and total internal reflection microscopy (TIRFM) experiments show that ZnT-1 expression specifically decreased the abundance of the LTCC α1-subunit at the cell surface.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Xenopus Oocytes

Xenopus laevis frogs were maintained and dissected as described previously (42). Oocytes were surgically removed from mature female X. laevis and deflocculated by incubation with 1.5 mg/ml collagenase for 0.5–1 h. Fully grown stage VI oocytes were isolated and allowed to recover at 18 °C in ND96 solution containing (in mm): 96 NaCl, 2 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 2.5 sodium pyruvate, and 5 HEPES (pH 7.5), plus 50 μg/ml gentamycin.

Expression of LTCC and ZnT-1 in Xenopus Oocytes

Complementary cRNAs encoding for the cardiac and skeletal muscle isoforms of three L-type Ca2+ channel subunits (α1, β2a, and α2δ) and of ZnT-1 were synthesized by in vitro transcription with T7 or an SP6 Amplicap High-Yield Message Maker Kit (Epicenter Technologies, Madison, WI). The recombinant plasmids used in these reactions were α1cGSB (rabbit cardiac α1C (43)), pSPCA1 (rabbit skeletal muscle α2δ (43)), pSPOTR-β2a (rabbit β2a (44)), and pXen1-ZnT-1 (rabbit ZnT-1 (45)). Unless otherwise indicated, equal amounts (2.5 ng) of cRNAs of α1c, a2δ, and β2a with or without cRNA of ZnT-1 (2.5 ng) were injected into the oocytes as previously described (31). Injected oocytes were stored at 18 °C for 5 days in ND96 solution prior to electrophysiological recordings.

IBa Recordings in Xenopus Oocytes

Currents were monitored by two-electrode voltage clamp using a Gene Clamp 500 amplifier (Molecular Devices Corp., Sunnyvale, CA), as previously described (31). The bath solution contained (in mm): 40 Ba(OH)2, 50 NaOH, 2 KOH, and 5 HEPES (titrated to pH 7.5 with methanesulfonic acid). Oocytes were injected with 25 nl of 50 mm 1,2-bis(2-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid 30 min before measurements to minimize the opening of calcium-dependent chloride channels. Ba2+ currents were measured in response to 200-ms voltage clamp pulses generated every 2 s starting from a holding potential of −80 mV to test potentials ranging from −80 mV to +50 mV. Currents in non-injected oocytes were negligible.

Data Analysis

The current-voltage (I-V) curve was fitted with the Boltzmann equation as previously described (46). Conductance (G) was calculated according to the equation: G = I/(Vm − Vrev), where I and V are the measured current and membrane potential, respectively, and Vrev is the measured reversal potential. The obtained data were normalized to the maximal value of G for the purpose of calculating the fractional conductance (G/Gmax) at each Vm, using the equation G/Gmax = I/(Gmax(Vm − Vrev)).

Cell Culture and Transfection

Human embryonic kidney (HEK293T) cells and Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO) were maintained in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with (v/v) 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% l-glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator (all from Bet-Haemek, Israel). One day before transfection, the cells were subcultured into 60-mm culture dishes and seeded to reach 60–70% confluency. HEK293T cells were transfected utilizing a calcium phosphate transfection protocol as previously described (47). CHO cells were transfected utilizing Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmids Used for Expression of LTCC and ZnT-1 in HEK293T and CHO Cells

Several recombinant plasmids were used for expressing L-type Ca2+ channel subunits and ZnT-1. Two types of CaV1.2a plasmids were used: pcDNA3-HK1 (CaV1.2a (α1C) rabbit heart) and YH-CaV1.2 (a CaV1.2 fused to yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in the intracellular N terminus and hemagglutinin epitope in the extracellular S5–H5 loop of domain II) as previously described (25). Three different plasmids were used for expressing β2a: pcDNA3-β2a (β2a rabbit), β2a-pECFP-N1 (rabbit β2a tagged with CFP), and β2a- Cerulean-N1 (rabbit β2a tagged with Cerulean). Four different ZnT-1 plasmids were used: ZnT-1-pJJ19 (rabbit ZnT-1 tagged with myc), ZnT-1-pEYFP-N1 (rabbit ZnT-1 tagged with YFP), ZnT-1-Venus-N1 (rabbit ZnT-1 tagged with Venus), and ZnT-1-pECFP-N1 (rabbit ZnT-1 tagged with CFP). Control cells were transfected with the empty pcDNA3 vector. Experiments were carried out 36–48 h after transfection.

Primary Cardiomyocyte Cultures

Cardiomyocytes from 1- to 2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Israel) were isolated and cultured as previously described (31, 48). Briefly, heart ventricles were dissociated enzymatically with RDB (Israel Institute of Biology, Ness Ziona, Israel). The dispersed cells were then resuspended in growth medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented with 10% horse serum, 100 μg of penicillin, and 100 μg of streptomycin, Biological Industries, Bet-Haemek, Israel) and incubated for 10 min. The myocyte-enriched fraction of the cells was plated, at a density of 1 × 106 cells/dish, onto collagen-elastin-coated glass coverslips placed in 60-mm culture dishes. The cardiomyocytes were washed, and the medium was replaced 24 and 48 h after seeding.

Electrical Stimulation of Cultured Cardiomyocytes

Cardiomyocytes were stimulated by bipolar platinum electrodes embedded in the culture dish as previously described (31). For this purpose, rectangular pulses of 2- to 6-ms duration were applied by a conventional electrophysiological pacer (Model 5328, Metronix). Capture of the electrical stimulus and the subsequent cell contractions was assessed visually at a slow pacing frequency using an inverted microscope. Thereafter, the dish was placed in an incubator, and the cardiomyocytes were stimulated using double threshold intensity at 10 Hz (i.e. 600 beats per minute) for 4 h. In all trials, the stimulus capture was verified (by viewing the contractions) following the incubation period.

Plasmid Construction

ZnT-1-pEYFP-N1 and ZnT-1-pECFP-N1 were cloned by transfer of full-length ZnT-1 from the ZnT-1-pJJ19 plasmid, upstream of EYFP and ECFP in pEYFP-N1 and pECFP-N1, respectively (Clontech, enhanced yellow/cyan fluorescent protein). β2a-pECFP-N1 was cloned by amplifying full-length β2a by PCR and ligating it into the pECFP-N1 vector between the BglI and EcoRI sites upstream of ECFP, followed by sequence verification.

ZnT-1-Venus and β2a-Cerulean were produced by subcloning full-length ZnT-1 and β2a into Venus and Cerulean vectors, respectively, which are based on the pEGFPN1 backbone (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). Venus (51) and Cerulean (50) were kindly supplied by Prof. Atsushi Miyawaki from RIKEN and Prof. David Piston from Vanderbilt University, respectively.

Western Blot Analysis

To harvest cellular proteins (31), cultured cells were washed three times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), scraped with a rubber policeman, and homogenized by sonication in 150 μl of Choi homogenizing buffer containing (in mm): 20 Tris-HCl, 320 sucrose, 0.2 EDTA, 0.5 EGTA, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Boehringer Complete Protease Inhibitor Mixture, Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Germany). The homogenate was cleared at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was frozen and stored at −80 °C for future use. Xenopus oocytes were lysed with Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (0.5% Nonidet P-40, Igepal), containing (in mm): 137 NaCl, 50 NaF, 5 EDTA, 10 Tris (pH 7.5), 1 NaVO3, and a protease inhibitor mixture as above. Lysates were cleared by low speed centrifugation (820 × g for 15 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant was frozen and stored at −80 °C for future use. Protein concentrations were determined utilizing the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (31). ZnT-1 was detected with anti sera against ZnT-1 (37); the LTCC α1C subunit was detected with anti-α1C (Alamone Laboratories); and the β subunit was detected with anti-sera against β2a (a generous gift from Prof. F. Hofmann, Technical University, Munich, Germany); Na/K-ATPase was detected with anti-sera against Na/K-ATPase as previously described (49).

Co-immunoprecipitation

Protein lysates of HEK293T cells or Xenopus oocytes expressing the β2a subunit and Myc-tagged ZnT-1 were prepared as described above. A mouse monoclonal anti-Myc IgG antibody (∼10 μg, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) was added to the relevant lysate, and the mixture was incubated for 2–3 h at 4 °C. Thereafter, pre-washed Protein G-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was added to the samples to pull down ZnT-1, and the mixtures were incubated at 4 °C for another 2–3 h, followed by four wash cycles with Choi lysis buffer. The final step comprised immunoblotting, i.e. SDS-PAGE, membrane blotting, and probing with rabbit anti-β2a and mouse monoclonal anti-Myc antibodies followed by goat anti-rabbit and goat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase-tagged secondary antibodies, respectively (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Detection was performed as previously described (31).

Surface Biotinylation

HEK293T cells and primary cardiomyocytes were subcultured into 60-mm cultures. The following day, HEK293T cells were transfected with the α1- and β-subunits of the LTCC with or without ZnT-1 (as described above). 72 h following cell seeding, the cell monolayers were washed three times with ice-cold PBS, and then incubated for 30 min at 4 °C, with gentle shaking, with the membrane-impermeable reagent Sulfo-NHS-SS-biotin (Pierce) at a concentration of 0.5 mg/ml in the PBS. The cells were then extensively washed with PBS supplemented with 10% bovine serum albumin (Sigma). The cells were then scraped into 150 μl of ice-cold harvest buffer (in mm): 20 Tris, pH 8.0, 137 NaCl, 5 EDTA, 5 EGTA, 10% glycerol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 50 NaF, 20 benzamide (Sigma), and a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche Applied Science). The tubes were sonicated (10 s) and centrifuged (3000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C), and the supernatant fraction was isolated. Protein content was determined using the Bio-Rad assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard. All samples were adjusted to similar protein concentrations with harvest buffer. From each sample 60 mg was retained and designated the “Total Protein” fraction. 30 μl of immobilized NeutrAvidin (Thermo Scientific) was added to the remaining samples, and the reaction was gently rotated end over end at 4 °C for 10 h. The resin was spun down (8000 × g, 5 min) and washed three times with ice-cold harvest buffer. Samples containing the released protein, designated “Membrane Fraction” were stored at −80 °C for Western blot analysis. Western blot analysis of the “Total Protein” and “Membrane Fraction” samples was performed as described above. Ponceau staining was used to confirm equal protein loading. To ascertain lack of cytoplasmic contamination in the biotinylation eluate we tested for the absence of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the biotinylated samples.

Measurement of FRET

FRET was measured by sensitized emission, using the spectral FRET method (50) modified as described below. Cells were imaged using a Nikon C1Si spectral confocal microscope mounted on a Nikon FN1 upright microscope, using a 60× 1.0 numerical aperture water immersion objective. A 405 nm laser diode was used to excite Cerulean (51), the donor within the FRET pair, while the 488 nm line from a multiline argon ion laser (both Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA) was used to excite Venus (52), the acceptor. 405 nm and 488 nm dichroic mirrors, respectively (Chroma, Rockingham, VT), were used to separate excitation and emission. The emission spectrum was measured in parallel at a spectral resolution of 5 nm, at a range of 430–590 nm for 408 nm excitation (32 channels) and 495–590 nm for 488 nm excitation (19 channels). The spectra were analyzed quantitatively by spectral unmixing against fluorescence references measured separately in cells expressing exclusively the donor or the acceptor. Unmixing was performed using an in-house analysis package written in OriginLab (Northampton, MA). Briefly, the emission spectra were fit by the least-squares method with the weighted average of predefined arbitrary functions describing the premeasured fluorescence spectra of the donor and acceptor, as well as of the autofluorescence of the cells. The emission of the acceptor was corrected by subtracting the emission of the acceptor due to direct excitation by the 408 nm line, calculated using a parallel 488 nm image multiplied by a separately determined correction factor. Finally, we calculated the apparent FRET efficiency, which is the integral of the corrected acceptor emission divided by sum of the donor and corrected acceptor emissions. The apparent FRET efficiency is linearly proportional but not equal to the true FRET efficiency, due to instrument-specific factors. As a positive FRET control we imaged cells expressing the Cer20Ven fusion protein, in which Cerulean is fused by a 20-amino acid linker to Venus as compared with Cerulean and Venus expressed separately (Fig. 2, C and D).

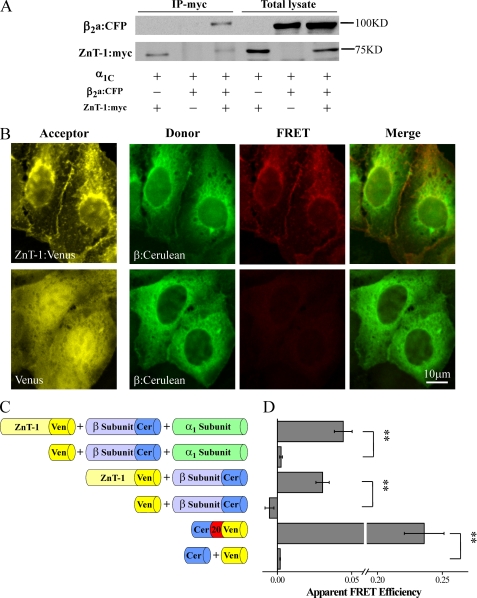

FIGURE 2.

ZnT-1 interacts with the LTCC β2a-subunit. A, HEK293T cells were co-transfected with LTCC subunits α1C, β2a:CFP, and ZnT-1:myc. Protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and probed with anti-Myc and anti-β2a antibodies. Shown is a representative blot out of six independent experiments. B, fluorescence images of HEK293T cells expressing ZnT-1:Venus (top) or free Venus (bottom) as the acceptor and β:Cerulean as the donor (without exogenous α1-subunit). Images of direct excitation of the acceptor (left, 488 nm laser line, shown in yellow) reveal its localization in both cell types. Spectral stacks obtained by exciting the donor (408 nm laser line) were unmixed into donor emissions (green) and acceptor sensitized-emission components (red) and are presented also as merged images. FRET was observed only in cells expressing ZnT-1:Venus. C, schematic diagram of the design of the quantitative FRET experiments. D, cells co-expressing LTCC subunits (untagged α1C and β:Cerulean) and ZnT-1:Venus exhibited FRET (0.044 ± 0.005, n = 87 in four independent experiments) as compared with cells co-expressing untagged α1C, β:Cerulean, and free Venus (0.003 ± 0, n = 36; **, p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney non-parametric U test). Cells expressing β:Cerulean and ZnT-1:Venus in the absence of untagged α1C-subunit also exhibited FRET (0.030 ± 0.005, n = 66 in three independent experiments) as compared with cells expressing β:Cerulean and free Venus (−0.005 ± 0.003, n = 63; **, p < 0.01). As a positive control, FRET was measured in cells expressing a Cerulean-Venus fusion protein (Cer20Ven; 0.236 ± 0.015, n = 70) as compared with cells expressing free Cerulean and Venus (0.002 ± 0, n = 49; **, p < 0.01).

TIRFM

CHO cells grown in a glass-bottom dish were transfected with LTCC and ZnT-1. At 24 h after transfection, cells were fixed for 20 min with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS, and then imaged in standard PBS solution at room temperature. Imaging was performed on an in-house built prism-based TIRFM system, using the 488 nm line of an argon ion laser (Melles Griot). Cells were imaged with a SPOT charge-coupled device camera (Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI), mounted on a Zeiss Axioplan2 upright light microscope equipped with a 40×, 1.3 numerical aperture objective (Zeiss, Jena, Germany).

To quantify changes in TIRFM of EYFP-labeled proteins, intensities of the regions of interest of several cells were normalized according to the following equation: relative fluorescence intensity = F(t)/F(e), where F(t) is the intensity of TIRFM measurements and F(e) is the intensity of epifluorescence measurements. The relative fluorescence intensity was determined using the ImageJ software package. The relationship between ZnT-1 expression and the relative fluorescence intensity of the α1-subunit was fit with the function, Rmax/(1 + F/Ki), where Rmax is the relative fluorescence intensity in the absence of ZnT-1, Ki is the ZnT-1 fluorescence at which the half-maximal inhibition is obtained, and F is the ZnT-1 fluorescence, all at a given α1-subunit quantity.

Statistical Analysis

Values were expressed as means ± S.E. Student's t test was used as required to determine statistical significance of differences between means. For results that were distributed in a non-Gaussian manner, the Mann-Whitney non-parametric test was used, as indicated. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. In all figures, * signifies p < 0.05, and ** p < 0.01.

RESULTS

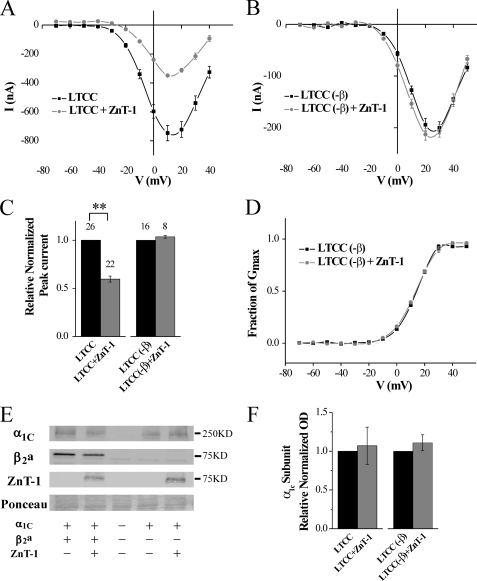

The β-Subunit Is Essential for LTCC Inhibition by ZnT-1

We first examined whether the action of ZnT-1 depends on the presence of the β-subunit. The regulation of LTCC by ZnT-1 was assessed by measuring Ba2+ currents utilizing the two-electrode voltage clamp technique in Xenopus oocytes co-expressing ZnT-1 and the LTCC subunits. As was previously demonstrated (31), in the presence of the β-subunit, ZnT-1 reduced the LTCC peak current to 59.5 ± 3.2% of its value, without altering its steady-state activation (Fig. 1A), reversal potential, half-maximum conductance (½Gmax) or the z-effective charge of gating (Table 1). Further, ZnT-1 did not affect the total expression of the LTCC α1-subunit (Fig. 1, E and F). Omission of the β-subunit significantly reduced the peak LTCC current and shifted it to more depolarized values by ∼20–30 mV (Fig. 1, compare B to A; see Table 1), due to lesser targeting of the α1-subunit to the membrane (46). However, as we hypothesized, ZnT-1 did not further inhibit the remaining LTCC current, yielding 104 ± 1% of the value recorded in the absence of ZnT-1 under similar conditions (Fig. 1C). ZnT-1 did not affect the reversal potential of the LTCC (Table 1), its steady-state activation (Fig. 1D), ½Gmax, or z-effective gating charge (Table 1). The total expression of the LTCC α1-subunit was also unaltered significantly (Fig. 1, E and F). In conclusion, ZnT-1 affected only the LTCC peak current, specifically in the presence of the β-subunit, consistent with our hypothesis that ZnT-1 inhibits LTCC currents by interacting with the β-subunit and not the α1-subunit.

FIGURE 1.

LTCC currents are not inhibited by ZnT-1 in Xenopus oocytes in the absence of the β-subunit. A, steady-state current-voltage (I-V) relationship of Ba2+ currents. Currents were measured 5 days after the oocytes had been co-injected with cRNA for the α1C, β2a, and α2δ cardiac LTCC subunits, with (n = 3) or without ZnT-1 (n = 5). Data from a representative experiment are shown as mean ± S.E. of individual oocyte currents. B, Ba2+ currents as in A but measured in oocytes expressing only the α1C and α2δ LTCC subunits in the presence (n = 3) or absence (n = 4) of ZnT-1. C, normalized peak currents as depicted in A and B from five and three independent experiments, respectively. Co-expression of ZnT-1 reduced the relative normalized peak current by 40.5 ± 3.2% (n = 22 and 26 oocytes, with and without ZnT-1; **, p < 0.01). In the absence of the β-subunit, ZnT-1 did not inhibit the LTCC (n = 8 and 16 oocytes with and without ZnT-1, p > 0.1). D, voltage dependence of the fractional conductance (G/Gmax), derived from the data shown in B. The line depicts fitting of the data to the Boltzmann equation and the yielded parameters (½Gmax and z-effective gating charge) are depicted in Table 1. E, expression of α1C-subunit, β2a-subunit, and ZnT-1 in the oocytes. The figure shows a representative blot out of three independent blots. Ponceau staining (lower panel) is shown as a loading control. F, normalized densitometry value of LTCC α1C-subunit in total oocytes lysates. Co-expression of ZnT-1 with LTCC (in the presence or absence of β-subunit) did not lead to a significant change in the expression of α1-subunits in total oocytes lysates (p > 0.1).

TABLE 1.

Relative changes in the normalized peak current, reverse potential, ½Gmax and z-effective gating charge caused by co-expression of ZnT-1

| Group | Normalized IBa | Vrev | ½Gmax | z-effective gating charge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mV | ||||

| LTCC | ||||

| No ZnT-1 | 1 | 56.0 ± 0.6 | −0.23 ± 0.74 | 3.11 ± 0.05 |

| With ZnT-1 | 0.59 ± 0.32 | 54.1 ± 1.1 | 1.43 ± 0.62 | 3.05 ± 0.05 |

| LTCC (no β) | ||||

| No ZnT-1 | 1 | 62.7 ± 0.3 | 14.17 ± 0.11 | 3.57 ± 0.07 |

| With ZnT-1 | 1.04 ± 0.01 | 57.8 ± 0.2 | 13.03 ± 0.30 | 3.08 ± 0.13 |

| LTCC (β×5) | ||||

| No ZnT-1 | 1 | 57.1 ± 0.3 | −2.66 ± 0.52 | 3.88 ± 0.06 |

| With ZnT-1 | 1.00 ± 0.01 | 57.9 ± 0.9 | −1.53 ± 0.64 | 4.01 ± 0.08 |

The values of ½Gmax and z-effective gating charge were obtained in each cell by fitting the I-V curve to the Boltzmann equation. Mean ± S.E. are shown.

½Gmax is the voltage that causes half-maximal activation.

ZnT-1 Interacts with the β-Subunit

Based on our findings of the specific role of the β-subunit in modulation of LTCC current by Znt-1, we next examined whether ZnT-1 and the β-subunit interact. To test this possibility, we examined whether immunoprecipitating ZnT-1 pulls down the β-subunit. For this purpose, the LTCC α1C- and β:CFP-subunits were co-expressed with ZnT-1:Myc in HEK293T cells, and ZnT-1 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody. Fig. 2A demonstrates that the β-subunit was indeed specifically co-precipitated by ZnT-1. To confirm an interaction between ZnT-1 and the β subunit, FRET between fluorescently labeled ZnT-1 and the β-subunit was measured (Fig. 2, B–D). FRET is a well accepted method for quantifying protein-protein interactions, because it occurs only when the tagged proteins of interest are within molecular-range distance (<10 nm) of each other (53). FRET was measured in cells co-expressing the untagged α1-subunit, β:Cerulean, and ZnT-1:Venus, but not in cells expressing the untagged α1-subunit along with β:Cerulean and free Venus, consistent with an interaction between ZnT-1 and the LTCC β-subunit in the presence of α1-subunit. Such an interaction could be mediated by the untagged α1-subunit. However, FRET was measured also in its absence (Fig. 2, B–D), indicating that the α1-subunit is not obligatory for such an interaction. Taken together, these results strongly suggest an in situ interaction between ZnT-1 and the LTCC β-subunit in the presence or absence of the α1-subunit.

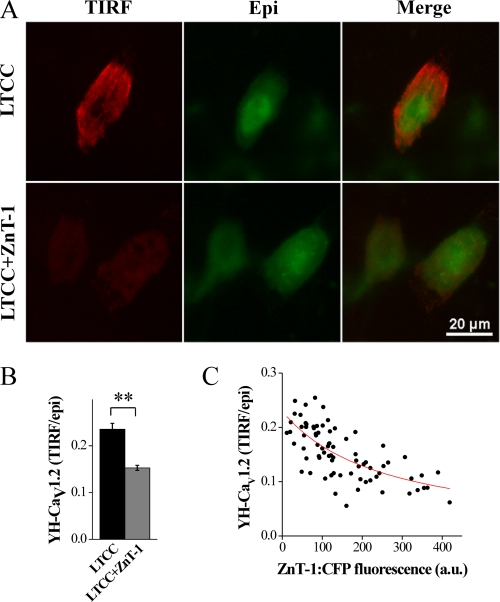

ZnT-1 Down-regulates the Surface Membrane Expression of LTCC α1-Subunits

The β-subunit is known to participate in trafficking of the α1-subunit to the membrane (26, 27). Because ZnT-1 inhibits LTCC currents without affecting the expression level of the α1-subunit (Fig. 1) and interacts with the β-subunit (Fig. 2), we hypothesized that the inhibition of LTCC currents by ZnT-1 is mediated by a reduction in membrane targeting of the α1-subunit of the LTCC by ZnT-1. To address this issue, membrane insertion of the α1-subunit was examined by biotinylating membrane-inserted proteins in intact HEK293 cells, then pulling down the membrane proteins and determining the relative representation of the α1-subunit at the membrane versus its total quantity. Our results show that co-expression of ZnT-1 lowered the membrane fraction of the LTCC α1-subunit without affecting its total expression (Fig. 3, A and B).

FIGURE 3.

ZnT-1 reduces the cell surface expression of the LTCC α1-subunit. A, Western blot analysis (using an anti-CaV1.2 antibody, upper blot) of biotinylated whole cell lysates (left) and plasma membranes (right) obtained from HEK293T cells co-expressing the LTCC α1C- and β-subunits with or without ZnT-1 (control cells were transfected with pcDNA). A representative blot (n = 5) is depicted. Ponceau staining was used to confirm equal protein loading (middle blot). The cytoplasmic protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) could not be detected in the eluate from the biotinylation (bottom blot), indicating lack of contamination of the membrane fraction with cytoplasmic proteins. B, normalized densitometry value of LTCC α1C-subunit in whole cell lysates (Total), and plasma membranes (Surface). Co-expression of ZnT-1 with the LTCC led to a significant reduction in the surface expression of the α1-subunit (by 52.9 ± 5.8%; **, p < 0.01), with no change in the expression of the α1-subunit in whole cell lysates (p > 0.1). C, representative Western blot of ZnT-1 following 4 h of rapid pacing (RP). Rapid pacing led to a marked increase in the expression of ZnT-1. D, Western blot analysis (using an anti-CaV1.2 antibody, upper blot) of biotinylated whole cell lysates (left) and plasma membranes (right) obtained from control (C) cultured cardiomyocytes and cardiomyocytes that underwent rapid pacing (RP). Anti-Na/K-ATPase antibody was used as a negative control (middle blot). A representative blot (n = 5) is depicted. Normalized densitometry values of LTCC α1C-subunit (E) and Na/K-ATPase (F) in whole cell lysates (Total), and plasma membranes (Surface) are shown. Rapid pacing for 4 h led to a significant reduction in the surface expression of the α1-subunit (by 53.0 ± 5.8%; **, p < 0.01), with no change in the expression of α1-subunits in whole cell lysates (p > 0.1). Rapid pacing did not decrease the membrane fraction of the Na/K-ATPase.

To verify the generality of this central observation, we examined the membrane presentation of the LTCC α1-subunit in cultured cardiomyocytes. Rapid electrical pacing has been shown to decrease LTCC activity in cardiomyocytes in lieu of an increase in the expression of endogenous ZnT-1 (31), providing us with a physiologically relevant platform for this evaluation. Following 4 h of rapid pacing, ZnT-1 expression is indeed augmented (Fig. 3C and see Ref. 31). Biotinylation experiments indicate a marked reduction in the surface expression of the LTCC α1-subunit in these cells (Fig. 3, D and E), in agreement with our results in HEK293 cells. No change is seen in the surface expression of the Na/K ATPase (Fig. 3, D and E), refuting a general decrease in the presentation of membrane proteins (p < 0.01 and p > 0.1 for LTCC α1-subunit and Na/K ATPase, respectively).

To further confirm the effect of ZnT-1 on the plasma membrane presentation of the α1-subunit, TIRFM was used to image membrane localization of YFP-labeled α1-subunit (Fig. 4A). TIRFM enables quantification of fluorescently tagged proteins localized close to or at the cell surface (54). In TIRFM only those fluorophores located within a few hundred nanometers of the glass interface are excited, thus avoiding observation of most of the cytosolic fraction. A relative measure of the membrane fraction was defined as the ratio between the TIRFM signal, representing the membrane-inserted protein, and the conventional epifluorescence signal, representing total protein expression. Co-expression of the LTCC with ZnT-1 led to a 28.7 ± 6.7% (p < 0.01) reduction in the relative signal of the α1-subunit at the cell surface versus cells expressing LTCC alone (Fig. 4B). Importantly, LTCC surface expression was negatively correlated to the degree of ZnT-1 expression (Fig. 4C). In conclusion, biotinylation and TIRFM experiments confirmed independently that ZnT-1 specifically decreases the targeting of the LTCC α1-subunit to the cell surface.

FIGURE 4.

TIRFM evaluation shows reduction of the surface expression of the α1-subunit by ZnT-1. A, CHO cells co-expressing YH-CaV1.2 (YFP-tagged LTCC α1C) and the β-subunit with (bottom) or without (top) ZnT-1:CFP. TIRFM illumination (left, red) and epifluorescence (middle, green), both exclusively of YFP. A merged image of TIRFM and epifluorescence is shown on the right. B, ZnT-1 expression led to a reduction of α1 membrane localization. Shown is the ratio of YFP fluorescence in the TIRFM and epifluorescence channels. ZnT-1 reduced the ratio to 71.3 ± 6.7% of the control value (**, p < 0.01, n = 60 and 76 cells with and without ZnT-1, respectively, in two independent experiments). C, ratio of TIRFM to epifluorescence as a function of ZnT-1:CFP fluorescence intensity. A negative dose-dependent relationship is evident between the expression of the ZnT-1 and the membrane localization of the α1-subunit (n = 76). The data were fit (red line) with a function describing competitive inhibition by ZnT-1.

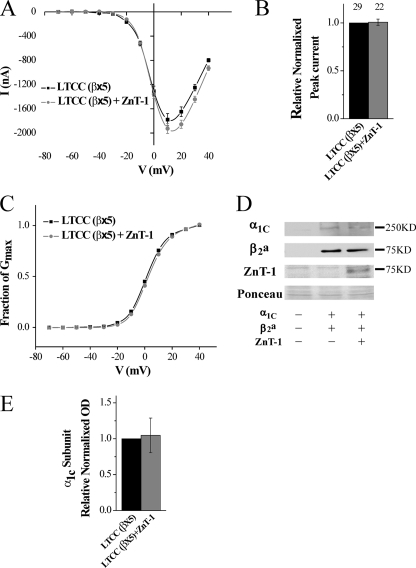

ZnT-1 Does Not Inhibit the LTCC in the Presence of Excess β-Subunit Expression

The data presented above indicate that ZnT-1 interacts with the β-subunit, thereby interfering with its chaperone function (see “Discussion”). It is therefore predicted that excess expression of the β-subunit will counteract the ZnT-1-induced LTCC inhibition, by saturating ZnT-1 and thus maintaining a free fraction of β-subunit that is capable of facilitating targeting of the α1-subunit to the membrane. This assumption was tested by monitoring the LTCC current in oocytes that overexpress the β-subunit in relation to the other components of the LTCC. For this purpose, oocytes were injected with β-subunit RNA at 12.5 ng/oocyte, which is five times higher than the concentration used in the experiments depicted in Fig. 1A. Indeed, in the presence of excess β-subunit (β×5), ZnT-1 did not inhibit the LTCC current (Fig. 5, A and B). As before, ZnT-1 did not affect the reversal potential, did not lead to a shift in the peak current on the voltage axis (Fig. 5A), had no effect on the parameters of the steady-state activation of the LTCC (Fig. 5C and Table 1), and did not significantly change the total expression of the LTCC α1-subunit (Fig. 5, D and E). In summary, ZnT-1 completely failed to inhibit the LTCC in the presence of excess β-subunit expression, thus providing further support to our proposed model.

FIGURE 5.

LTCC current is not inhibited by ZnT-1 in the presence of excess β-subunit. A, steady-state current-voltage (I-V) relationship of Ba2+ currents in oocytes. Currents were measured 5 days after the oocytes were co-injected with the three cardiac isoforms of the LTCC subunits α1C, β2a (×5 the quantity in Fig. 1), and α2δ, with (n = 12) or without (n = 13) ZnT-1. Data from a representative experiment are shown as mean (±S.E.) currents of individual oocyte currents. B, normalized peak currents as in A from three independent experiments. Co-expression of ZnT-1 in the presence of excess of the LTCC β-subunit (β×5; n = 22) failed to inhibit the channel (control; n = 29, p > 0.1). C, voltage dependence of the fractional conductance (G/Gmax), derived from the data shown in A. The line depicts fitting of the data to the Boltzmann equation. The yielded parameters (½Gmax and Z effective gating charge) are included in Table 1. D, expression levels of the α1C, β2 (×5), and ZnT-1 in the oocytes. Shown is a representative blot out of three independent blots. Ponceau staining (lower panel) is shown as a loading control. E, normalized densitometry value of the LTCC α1C-subunit in total oocytes lysates. Co-expression of ZnT-1 with LTCC (β2 (×5)) did not lead to a significant change in the expression of α1-subunits in total oocytes lysates (p > 0.1).

DISCUSSION

The LTCC is expressed in many organs, and its proper activity is essential for a large number of physiological functions (8). Recent studies have shown that ZnT-1 is an endogenous negative regulator of the LTCC (30, 31), particularly in the heart, where it appears to participate in cardiac electrical remodeling following atrial fibrillation (31), and in the brain, where it may affect synaptic release (37, 40). Nevertheless, the mechanism underlying ZnT-1-induced inhibition of the LTCC has yet to be elucidated. Here, we propose that ZnT-1 regulates the LTCC by interacting with its regulatory β-subunit thus limiting the plasma membrane expression of the LTCC. The main findings of the present work are: 1) the inhibitory effect of ZnT-1 exhibits a tight stoichiometric relationship between ZnT-1 and the β-subunit, because both excess and absence of the β-subunit abolished it; 2) there is a molecular interaction between ZnT-1 and the β-subunit; and 3) overexpression or endogenous induction of ZnT-1 down-regulates the translocation of LTCC α1-subunit to the plasma membrane.

ZnT-1 has been shown to function primarily as a zinc transporter (35, 36, 47), and hence it has been studied mainly in the context of zinc metabolism in the brain (39, 47, 55, 56). It is believed to act as a metal ion extruder that, by facilitating efflux of divalent ions such as zinc, lowers their concentrations in the cytoplasm and consequently protects cells from zinc toxicity (32). In addition, recent reports now demonstrate that ZnT-1 inhibits influx of divalent ions (such as zinc, barium, and calcium) by blocking the voltage-dependent activity of the LTCC (30, 31, 40). Our electrophysiological recordings in Xenopus oocytes revealed that the inhibitory effect of ZnT-1 on LTCC currents was not accompanied by changes in the voltage-dependent steady-state activation of these channels (31). In the present study, we show that, in the absence of the β-subunit, i.e. when only the α1- and α2δ-subunits of the LTCC are expressed, ZnT-1 does not inhibit the LTCC at all.

Several attempts to explain the inhibitory effect of ZnT-1 by an interaction between ZnT-1 and the LTCC α1-subunit have failed (30).5 Conversely, our current data indicate, for the first time, that ZnT-1-induced inhibition of the LTCC involves an interaction between ZnT-1 and the β-subunit. This interaction was demonstrated both by co-immunoprecipitation of the two proteins and by measurement of a FRET signal between ZnT-1:Venus and β:Cerulean co-expressed in HEK293T cells, irrespective of the α1-subunit.

Scrutiny of the structure of the β-subunit and its ability to bind other proteins reveals that it is a plausible candidate for this role. The β-subunit is an intracellular protein that contains two main domains, the Src homology 3 (SH3) and guanylate kinase (GK) domains. These domains, characterized by membrane-associated guanylate kinase, are known to allow modulation of LTCC activity and α1-subunit trafficking (27, 57–61). The guanylate kinase domain contains the β-interaction domain, which binds directly to the α-interaction domain (AID) in the α1-subunit (62, 63). It has been shown that the β-interaction domain (BID) is an essential site for regulators of LTCC that interact with the β-subunits (61), which is consistent with the idea that β-interaction domain is a possible site for interaction with ZnT-1. Unlike the β-subunit, ZnT-1 is a transmembrane protein. It contains three main intracellular parts: the C and N termini and a large cytosolic histidine-rich loop (64), all of which are possible candidate interaction sites with the β-subunit. A high homology exists between the basic structure of ZnT-1 and the structures of the other members of the ZnT family. However, ZnT-1 is unique in two regions, the histidine-rich loop and part of its C terminus. These regions may therefore contain the key structural elements that enable the interaction of ZnT-1 with other proteins, including the β-subunit. The notion that the underlying mechanism for ZnT-1 activity involves protein-protein interaction has been shown previously in other systems (45, 65). Jirakulaporn et al. (45) reported that the ZnT-1 C-terminal segment binds to N-Raf (cytoplasmic protein) and by doing so activates the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade (ERK-MAPK). Moreover, their study also showed that high levels of free zinc impair the interaction between ZnT-1 and Raf-1, which may imply a conformational change of ZnT-1 in the presence of high zinc concentrations. It will therefore be intriguing to further examine the influence of zinc on the ZnT-1-β-subunit interaction described in the present work.

One of the key observations concerning ZnT-1-induced inhibition of the LTCC is that inhibition occurs despite the fact that the total expression of the LTCC α1-subunit remains unchanged. A similar phenomenon has been described for small G-proteins, such as Rad, GEM, and Kir in a series of well documented studies (21, 23, 66, 67). The model that explains the activity of RGK proteins (21) predicts that, by binding to the β-subunit, the RGKs inhibit some of its effects on the LTCC α1-subunit. Consequently, RGK proteins modulate the trafficking of the α1-subunit to the surface of the plasma membrane. We thus examined the possibility that ZnT-1 resembles RGKs in its interaction with the LTCC. Biotinylation experiments (Fig. 3) demonstrated that the expression of ZnT-1 did indeed markedly reduce the surface expression of the LTCC α1-subunit. This reduction occurred despite the fact that there was no change in the total expression of the channels in whole cell lysates, indicating that ZnT-1 indeed modulates trafficking of the LTCC α1-subunit to the plasma membrane.

We have previously shown that rapid electrical pacing of primary cultured cardiomyocytes augments the expression of ZnT-1 in conjunction with decreased divalent cation influx via the LTCC (31). Moreover, small interference RNA knockdown of ZnT-1 establishes a cause-effect relationship between ZnT-1 induction (by rapid pacing) and LTCC inhibition (31). We used this system to test whether ZnT-1 augmentation alters LTCC α1-subunit surface expression in a physiological context that does not involve exogenous ZnT-1 overexpression. The results demonstrate a marked reduction in the surface expression of LTCC α1-subunit following rapid electrical pacing (Fig. 3, C–E). This finding, as well as previous data showing that knockdown of endogenous ZnT-1 augments the LTCC activity in several experimental setups (31, 40), complements our results obtained in overexpression systems, exposing a functional role for the regulation of endogenous ZnT-1 expression in native cells in the context of calcium metabolism.

Our TIRFM results (Fig. 4) independently confirm the changes in surface expression of LTCC α1-subunit observed in the biotinylation experiments (Fig. 3). Importantly, using TIRFM we also illustrated a strong negative correlation between the level of ZnT-1 expression and the surface expression of the α1-subunit, further supporting our model for ZnT-1 regulation of LTCC function via the modulation of its trafficking to the membrane.

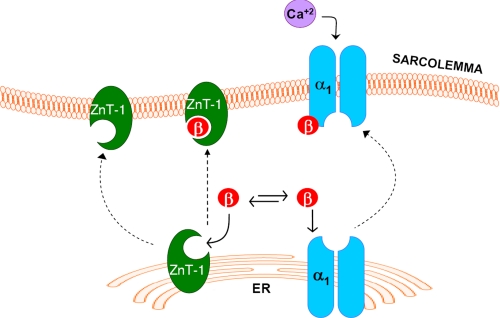

Finally, the essential role played by the β-subunit in ZnT-1-induced inhibition of the LTCC was examined by expressing excess quantities of the β-subunit in Xenopus oocytes. Under these conditions ZnT-1 failed to inhibit the LTCC currents, consistent with the β-subunit being the limiting component for inhibition of the LTCC by ZnT-1. Based on our results, we suggest that ZnT-1 interacts with the β-subunit, reducing its availability to bind the α1-subunit, thus inhibiting trafficking of the α1-subunit to the surface membrane (Fig. 6). Whether binding of ZnT-1 to the β subunit hinders binding between the two LTCC subunits or alternatively inhibits the translocation of the complex to the plasma membrane remains to be determined.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic diagram of the molecular mechanism for β-subunit dependent inhibition of the LTCC by ZnT-1. It is postulated that the interaction between ZnT-1 and the β-subunit sequesters the β-subunit, thus reducing its capacity to chaperone the α1-subunit to the plasma membrane, decreasing the surface expression of the channel. Consequently, there is a reduction in the LTCC currents with no change in the overall expression of the channel protein.

To conclude, the present study further validates the role played by ZnT-1 as an endogenous inhibitor of the LTCC in a physiologically relevant context. Moreover, it shows that the mechanism of action of ZnT-1 is specifically mediated by an interaction with the main regulatory subunit of the LTCC, the β-subunit. The entire repertoire of roles played by ZnT-1 in cell physiology and pathophysiology has not been elucidated, but the interaction of ZnT-1 with both Raf-1 (45) and the β-subunit, two different regulatory proteins, implies that ZnT-1 does indeed play vital roles that extend far beyond the regulation of zinc metabolism. It is therefore not surprising that deletion of ZnT-1 leads to early embryonic death (68). Certainly, the development of conditional, tissue-specific knockout models of ZnT-1 will be an important step in the further elucidation of this issue in the future.

This work was supported by German Israeli Foundation Grant I-850-263.2/2004 (to A. M., A. K., and Y. E.), by Israel Science Foundation Grants 992/07 (to A. M. and Y. E.) and 452/06 (to D. G.), by the Marc Rich Foundation for education, culture, and welfare (to D. G.), by the Chief Scientist Office of the Ministry of Health, Israel (to Y. E., A. K., and A. M.), and by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant MO 1932/1-1 (to A. M.).

O. Beharier, Y. Etzion, and A. Moran, unpublished data.

- LTCC

- L-type calcium channel

- RGK

- Rem, Rad, and Gem/kir family

- ZnT-1

- Zinc transporter 1

- FRET

- fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- TIRFM

- total internal reflection microscopy

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- EYFP

- enhanced YFP

- ECFP

- enhanced CFP

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bodi I., Mikala G., Koch S. E., Akhter S. A., Schwartz A. (2005) J. Clin. Invest. 115, 3306–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bannister R. A. (2007) J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 28, 275–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dulhunty A. F. (2006) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 33, 763–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kerfant B. G., Rose R. A., Sun H., Backx P. H. (2006) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 16, 250–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sonkusare S., Palade P. T., Marsh J. D., Telemaque S., Pesic A., Rusch N. J. (2006) Vascul. Pharmacol. 44, 131–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Catterall W. A., Perez-Reyes E., Snutch T. P., Striessnig J. (2005) Pharmacol. Rev. 57, 411–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moosmang S., Kleppisch T., Wegener J., Welling A., Hofmann F. (2007) Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 178, 469–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catterall W. A. (2000) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 16, 521–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nattel S., Burstein B., Dobrev D. (2008) Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. 1, 62–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee R., Spinale F. G. (1998) J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 30, 1899–1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakayama H., Chen X., Baines C. P., Klevitsky R., Zhang X., Zhang H., Jaleel N., Chua B. H., Hewett T. E., Robbins J., Houser S. R., Molkentin J. D. (2007) J. Clin. Invest. 117, 2431–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang S. N., Berggren P. O. (2006) Endocr. Rev. 27, 621–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Splawski I., Timothy K. W., Sharpe L. M., Decher N., Kumar P., Bloise R., Napolitano C., Schwartz P. J., Joseph R. M., Condouris K., Tager-Flusberg H., Priori S. G., Sanguinetti M. C., Keating M. T. (2004) Cell 119, 19–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Striessnig J. (1999) Cell Physiol. Biochem. 9, 242–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felix R., Gurnett C. A., De Waard M., Campbell K. P. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 6884–6891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee T. S., Ono K., Miyamoto S., Hadama T., Arita M. (2006) J. UOEH 28, 277–286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Catterall W. A., Striessnig J., Snutch T. P., Perez-Reyes E. (2003) Pharmacol. Rev. 55, 579–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi T., Yamada Y., Fukao M., Tsutsuura M., Tohse N. (2007) J. Pharmacol. Sci. 103, 347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McKeown L., Robinson P., Jones O. T. (2006) Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 27, 799–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singer-Lahat D., Gershon E., Lotan I., Hullin R., Biel M., Flockerzi V., Hofmann F., Dascal N. (1992) FEBS Lett. 306, 113–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balijepalli R. C., Lokuta A. J., Maertz N. A., Buck J. M., Haworth R. A., Valdivia H. H., Kamp T. J. (2003) Cardiovasc Res. 59, 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Béguin P., Mahalakshmi R. N., Nagashima K., Cher D. H., Ikeda H., Yamada Y., Seino Y., Hunziker W. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 355, 34–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Béguin P., Nagashima K., Gonoi T., Shibasaki T., Takahashi K., Kashima Y., Ozaki N., Geering K., Iwanaga T., Seino S. (2001) Nature 411, 701–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez-Ospina N., Tsuruta F., Barreto-Chang O., Hu L., Dolmetsch R. (2006) Cell 127, 591–606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green E. M., Barrett C. F., Bultynck G., Shamah S. M., Dolmetsch R. E. (2007) Neuron 55, 615–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamaguchi H., Hara M., Strobeck M., Fukasawa K., Schwartz A., Varadi G. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 19348–19356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.He L. L., Zhang Y., Chen Y. H., Yamada Y., Yang J. (2007) Biophys. J. 93, 834–845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang H. G., George M. S., Kim J., Wang C., Pitt G. S. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 9086–9093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balijepalli R. C., Foell J. D., Hall D. D., Hell J. W., Kamp T. J. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 7500–7505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Segal D., Ohana E., Besser L., Hershfinkel M., Moran A., Sekler I. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 323, 1145–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beharier O., Etzion Y., Katz A., Friedman H., Tenbosh N., Zacharish S., Bereza S., Goshen U., Moran A. (2007) Cell Calcium. 42, 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palmiter R., Findley S. D. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 639–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kambe T., Yamaguchi-Iwai Y., Sasaki R., Nagao M. (2004) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 61, 49–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cousins R. J., Blanchard R. K., Moore J. B., Cui L., Green C. L., Liuzzi J. P., Cao J., Bobo J. A. (2003) J. Nutr. 133, 1521S–1526S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cousins R. J., Liuzzi J. P., Lichten L. A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24085–24089Epub 22006 Jun 24022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmiter R. D., Huang L. (2004) Pflugers Arch. 447, 744–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nolte C., Gore A., Sekler I., Kresse W., Hershfinkel M., Hoffmann A., Kettenmann H., Moran A. (2004) Glia 48, 145–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim A. H., Sheline C. T., Tian M., Higashi T., McMahon R. J., Cousins R. J., Choi D. W. (2000) Brain Res. 886, 99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liuzzi J. P., Bobo J. A., Lichten L. A., Samuelson D. A., Cousins R. J. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 14355–14360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohana E., Sekler I., Kaisman T., Kahn N., Cove J., Silverman W. F., Amsterdam A., Hershfinkel M. (2006) J. Mol. Med. 84, 753–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nattel S. (2002) Nature 415, 219–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ohana E., Segal D., Palty R., Ton-That D., Moran A., Sensi S. L., Weiss J. H., Hershfinkel M., Sekler I. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4278–4284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mikami A., Imoto K., Tanabe T., Niidome T., Mori Y., Takeshima H., Narumiya S., Numa S. (1989) Nature 340, 230–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hullin R., Singer-Lahat D., Freichel M., Biel M., Dascal N., Hofmann F., Flockerzi V. (1992) EMBO J. 11, 885–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jirakulaporn T., Muslin A. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 27807–27815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanevsky N., Dascal N. (2006) J. General Physiol. 128, 15–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Majumder S., Ghoshal K., Summers D., Bai S., Datta J., Jacob S. T. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26216–26226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brik H., Shainberg A. (1990) Basic Res. Cardiol. 85, 237–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lubarski I., Pihakaski-Maunsbach K., Karlish S. J., Maunsbach A. B., Garty H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 37717–37724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takanishi C. L., Bykova E. A., Cheng W., Zheng J. (2006) Brain Res. 1091, 132–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rizzo M. A., Springer G. H., Granada B., Piston D. W. (2004) Nat. Biotechnol. 22, 445–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nagai T., Ibata K., Park E. S., Kubota M., Mikoshiba K., Miyawaki A. (2002) Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piston D. W., Kremers G. J. (2007) Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lavi Y., Edidin M. A., Gheber L. A. (2007) Biophys. J. 93, L35–L37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nitzan Y. B., Sekler I., Hershfinkel M., Moran A., Silverman W. F. (2002) Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 137, 149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsuda M., Imaizumi K., Katayama T., Kitagawa K., Wanaka A., Tohyama M., Takagi T. (1997) J. Neurosci. 17, 6678–6684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hanlon M. R., Berrow N. S., Dolphin A. C., Wallace B. A. (1999) FEBS Lett. 445, 366–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen N., Rickey J., Berfield J. L., Reith M. E. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5508–5519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Opatowsky Y., Chen C. C., Campbell K. P., Hirsch J. A. (2004) Neuron 42, 387–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Opatowsky Y., Chomsky-Hecht O., Kang M. G., Campbell K. P., Hirsch J. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 52323–52332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sasaki T., Shibasaki T., Béguin P., Nagashima K., Miyazaki M., Seino S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 9308–9312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Waard M., Pragnell M., Campbell K. P. (1994) Neuron 13, 495–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hidalgo P., Gonzalez-Gutierrez G., Garcia-Olivares J., Neely A. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 24104–24110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dufner-Beattie J., Langmade S. J., Wang F., Eide D., Andrews G. K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50142–50150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lazarczyk M., Pons C., Mendoza J. A., Cassonnet P., Jacob Y., Favre M. (2008) J. Exp. Med. 205, 35–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Finlin B. S., Crump S. M., Satin J., Andres D. A. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14469–14474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Murata M., Cingolani E., McDonald A. D., Donahue J. K., Marbán E. (2004) Circ. Res. 95, 398–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Langmade S. J., Ravindra R., Daniels P. J., Andrews G. K. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 34803–34809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]