Abstract

Aims

KCNQ1 (alias KvLQT1 or Kv7.1) and KCNE1 (alias IsK or minK) co-assemble to form the voltage-activated K+ channel responsible for IKs—a major repolarizing current in the human heart—and their dysfunction promotes cardiac arrhythmias. The channel is a component of larger macromolecular complexes containing known and undefined regulatory proteins. Thus, identification of proteins that modulate its biosynthesis, localization, activity, and/or degradation is of great interest from both a physiological and pathological point of view.

Methods and results

Using a yeast two-hybrid screening, we detected a direct interaction between β-tubulin and the KCNQ1 N-terminus. The interaction was confirmed by co-immunoprecipitation of β-tubulin and KCNQ1 in transfected COS-7 cells and in guinea pig cardiomyocytes. Using immunocytochemistry, we also found that they co-localized in cardiomyocytes. We tested the effects of microtubule-disrupting and -stabilizing agents (colchicine and taxol, respectively) on the KCNQ1–KCNE1 channel activity in COS-7 cells by means of the permeabilized-patch configuration of the patch-clamp technique. None of these agents altered IKs. In addition, colchicine did not modify the current response to osmotic challenge. On the other hand, the IKs response to protein kinase A (PKA)-mediated stimulation depended on microtubule polymerization in COS-7 cells and in cardiomyocytes. Strikingly, KCNQ1 channel and Yotiao phosphorylation by PKA—detected by phospho-specific antibodies—was maintained, as was the association of the two partners.

Conclusion

We propose that the KCNQ1–KCNE1 channel directly interacts with microtubules and that this interaction plays a major role in coupling PKA-dependent phosphorylation of KCNQ1 with IKs activation.

KEYWORDS: K+ channel, Myocytes, PKA, Signal transduction, KCNQ1, β-tubulin

1. Introduction

KCNQ1 (alias KvLQT1 or Kv7.1) is the α-subunit of a voltage-activated K+ channel expressed in cardiomyocytes.1,2 KCNQ1 associates with different β-subunits of the KCNE protein family.3 In particular, KCNQ1 and KCNE1 (alias IsK or minK) co-assemble to form a voltage-activated K+ channel characterized by its slow activation and deactivation kinetics. In the human heart, this heteromultimeric channel is responsible for the slow component of the delayed rectifier K+ current IKs, a major repolarizing current during the late phase of the action potential,4,5 especially during β1-adrenergic stimulation.6

There is growing evidence that ion channels are not moving freely along the membrane phospholipid bilayer plane but are instead organized rather intimately through interactions with other proteins. These interactions are instrumental for targeting and regionalizing ion channel proteins, but also for linking regulatory components to channels.7–9

KCNQ and KCNE subunits are part of large macromolecular complexes in various tissues. In cardiomyocytes, the KCNQ1–KCNE1 channel associates with T-cap, also called telethonin, thereby linking the sarcolemmal channel to myofibrils.10 As previously shown in different models, β-adrenergic stimulation of IKs requires the presence of a cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) anchoring protein (Yotiao, alias AKAP9, or other AKAPs) that keeps PKA in the vicinity of its target.11,12 In cardiomyocytes, Yotiao actively links the β-adrenergic stimulation to the channel activity by (i) keeping the PKA catalytic subunit, its regulatory subunit RII and the phosphatase PP1 close to the channel and (ii) permitting channel activation once phosphorylated.13,14

By making use of a yeast two-hybrid assay, we screened for other potential KCNQ1 partners. We found a physical association between KCNQ1 and β-tubulin, which could connect KCNQ1–KCNE1 channels to the cytoskeletal network. In order to evaluate the physiological relevance of this interaction, we investigated the effects of microtubule depolymerization on the channel activity using the permeabilized patch configuration of the patch-clamp technique on transfected COS-7 cells and on guinea pig cardiomyocytes. We observed that microtubule disruption did alter neither the channel activity nor its sensitivity to osmotic challenge. On the other hand, we demonstrated that the PKA-dependence of the current was altered after microtubule depolymerization, whereas channel phosphorylation, Yotiao phosphorylation, and the interaction between both proteins were not affected. Our data suggest that the microtubule cytoskeleton interacts with the KCNQ1 N-terminus and that this interaction is key for the coupling between phosphorylation and activation of KCNQ1–KCNE1 and hence for the regulation by β-adrenergic stimulation.

2. Methods

An expanded Methods section containing details for plasmids, yeast two-hybrid screening, co-immunoprecipitation, western blotting, immunocytochemistry, and electrophysiology is available only in the online data supplement. All procedures performed on animals were approved by the local committee for care and use of laboratory animals, and were performed according to strict governmental and international guidelines on animal experimentation. The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85–23, revised 1996).

2.1. Yeast two-hybrid screening

The KCNQ1 N-terminal domain (NtKCNQ1) was used as a bait. The yeast reporter strain L40 that contains the reporter genes lacZ and HIS3 downstream the binding sequences for LexA, was sequentially transformed with the pVJL10-NtKCNQ1 plasmid and with a mouse cDNA library, using the lithium acetate method15 and subsequently treated as described.16

2.2. Co-immunoprecipitation and western blotting

African green monkey kidney-derived COS-7 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA), guinea pig whole heart, rabbit anti-β-tubulin polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-KCNQ1-C-terminus (Ct-KCNQ1) polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), rabbit anti-KCNQ1 polyclonal antibody (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel), rabbit anti-Yotiao antibody (Zimed Laboratory Inc. or Fusion Antibodies), rabbit anti-phospho-S27 KCNQ1 antibody,17 rabbit anti-phospho- specific Yotiao antibody,14 mouse anti-vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) antibody (Sigma–Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and secondary horseradish peroxidase-coupled antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used.

2.3. Immunocytochemistry

Immunostaining was performed on COS-7 cells and on freshly isolated cardiomyocytes from guinea pigs using rabbit anti-β-tubulin, mouse anti-β-tubulin, goat anti-Ct-KCNQ1 polyclonal, or rabbit anti-KCNQ1 antibodies and Alexa A488-conjugated anti-rabbit or Alexa A568-conjugated anti-goat secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes). Metamorph (Roper Scientific SAS, Princeton Instruments, Tucso, AZ), Amira (Mercury Computer Systems SAS, Chelmsford, MA) and WCIF ImageJ (NIH) softwares were used for analysis.

2.4. Electrophysiology

Patch-clamp studies were performed on COS-7 cells transiently expressing KCNQ1, KCNE1 (pCI-KCNQ1 and pRC-KCNE1, respectively),18 Yotiao (pcDNA3-Yotiao),11 and GFP (pEGFP, Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) and on freshly isolated guinea pig cardiac myocytes using the permeabilized-patch configuration with amphotericin B at 35 ± 1°C. IKs was measured as the deactivating current at −40 mV in both cell types. For each set of experiments, untreated, taxol-, or colchicine-treated cells from the same transfected or isolated cell batch were investigated at the same time.

2.5. Statistics

The Costes randomization method (co-localization test plugin, ImageJ) was used to evaluate the significance of the confocal images.19 Protein phosphorylation variations on western blots were evaluated with the non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test. Patch-clamp results are presented as mean ± SEM of current densities. Statistical significance of the observed effects was assessed by an unpaired or paired Student's t-test or, when indicated, by one-way or two-way analysis of variance for repeated measures when appropriate, followed by a Tukey test when needed. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. The N-terminus of the KCNQ1 K+ channel interacts with β-tubulin in yeast

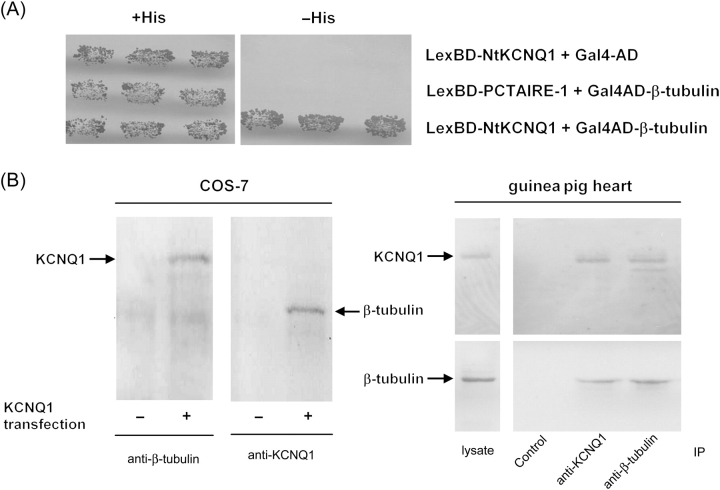

The yeast two-hybrid method was used to screen a mouse cDNA library using the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain of the KCNQ1 channel (amino acids 1–121, NtKCNQ1) as bait. Twenty interacting cDNA clones were isolated. DNA sequencing and database searching revealed that the nucleotide sequence of clone 5 encoded for about two-thirds of the length of the tubulin β2 isoform (amino acids 145–445). The specificity of the interaction was confirmed by co-transformation of clone 5 and bait into yeast in comparison with controls (Gal4-AD or LexBD-PCTAIRE-1; Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

β-tubulin associates with KCNQ1. (A) KCNQ1 N-terminus (NtKCNQ1) and β-tubulin binding in yeast. Yeast cells were co-transformed with plasmid pairs coding for the indicated proteins fused to LexA BD or Gal4 AD. Transformants were plated on synthetic medium with or without histidine (His). Each patch represents an independent transformant. (B) Interaction of full-length KCNQ1 and β-tubulin. Left, COS-7 cells were transfected (+) or not (−) with a KCNQ1 coding vector. Cell extracts were incubated with anti-β-tubulin or anti-KCNQ1 antibody. The immunoprecipitated protein complexes were examined by immunoblotting with anti-KCNQ1 (left) or anti-β-tubulin (right) antibody. Right, Guinea pig heart extract was incubated with anti-KCNQ1 or anti-β-tubulin antibody (IP). The lysate and immunoprecipitated protein complexes were examined by immunoblotting with anti-KCNQ1 (top) or anti-β-tubulin (bottom) antibody. Control lane: the immunoprecipitation was performed with the corresponding antibody exhausted with the appropriate blocking peptide.

3.2. β-Tubulin interacts with KCNQ1 K+ channel in transfected COS-7 cells and in the heart

In the quest for biochemical evidence for the interaction between the full-length KCNQ1 and β-tubulin, we immunoprecipitated the complex from the IGEPAL extract of KCNQ1-transfected COS-7 cells (Figure 1B) using antibodies against the KCNQ1 C-terminus or against β-tubulin. Western blotting analysis of KCNQ1 immunoprecipitates with a β-tubulin-specific antibody revealed co-precipitation of endogenous tubulin. Conversely, KCNQ1 was co-precipitated from a COS-7 cell lysate using a β-tubulin-specific antibody. Importantly, KCNQ1 and β-tubulin interaction were also consistently detected in the guinea pig heart by the same method (n = 3; Figure 1B).

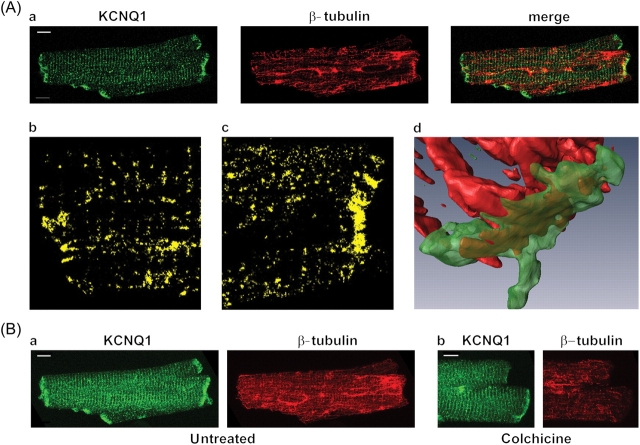

We determined the subcellular distribution of KCNQ1 and β-tubulin using confocal microscopy in guinea pig cardiomyocytes. As illustrated in Figure 2Aa, KCNQ1 is detected in the intercalated disks, t-tubules, and sarcolemma. Stacking of all confocal images of the same cell allows better visualization of KCNQ1 localization (Figure 2Ba, KCNQ1). Control experiments performed using a 10-fold excess of antigenic KCNQ1 peptide did not exhibit any labelling (not shown). Immunolabelling of β-tubulin revealed a microtubule network in cardiomyocytes (Figure 2Aa and Ba, β-tubulin) that partly co-localized with KCNQ1 (four independent experiments; Figure 2Aa–c, merge). A three-dimensional reconstruction of KCNQ1 and β-tubulin allowed better visualization of the protein co-localization at the intercalated disks (Figure 2Ad and see Supplementary material online). In order to quantify the co-localization, Pearson and Mander coefficients were calculated on the stack of 46 images of Figure 2B (see Supplementary material online, Table S1). To test the significance of the co-localization, the Pearson coefficient for the whole image (Rtotal: 0.17) was compared with the one obtained from 100 randomized images (mean Rrand: 0.014). Rtotal was always higher than Rrand obtained on each of the 100 iterations (Rtotal>Rrand: 100%).19 When non-specific co-localization was excluded by automatic thresholds for each fluorescence, a Pearson coefficient (Rcoloc) of 0.66 was calculated. The Mander coefficient for KCNQ1 (tM1) indicates that 60% of the channels co-localized with β-tubulin.

Figure 2.

KCNQ1 and β-tubulin localization in guinea pig cardiomyocytes. (A) Co-localization probed with KCNQ1- and β-tubulin-specific primary antibodies followed by fluorescence-labelled secondary antibodies. Single confocal images (a); KCNQ1 is shown in green and β-tubulin in red. Co-localization alone (yellow) is shown on the magnified views (b and c). Three-dimensional reconstruction of the intercalated disk zone (d). (B) Stack of 46 images for each protein in untreated (a) and colchicine-treated (b, 30 µM for 2 h) cardiomyocytes. Scale bars: 5 µm.

The effects of microtubule depolymerization on KCNQ1 localization were evaluated. After a 2-h pretreatment with 30 µM colchicine, KCNQ1 staining was not modified (Figure 2Bb).

Altogether, our results demonstrate the presence of a physical interaction between the KCNQ1 channel and β-tubulin in situ in cardiomyocytes, and that microtubule depolymerization does not modify KCNQ1 membrane expression. Therefore, we investigated the functional consequences of the KCNQ1 and β-tubulin interaction.

3.3. Microtubule targeting agents do not modify KCNQ1–KCNE1 K+ channel basal activity in COS-7 cells

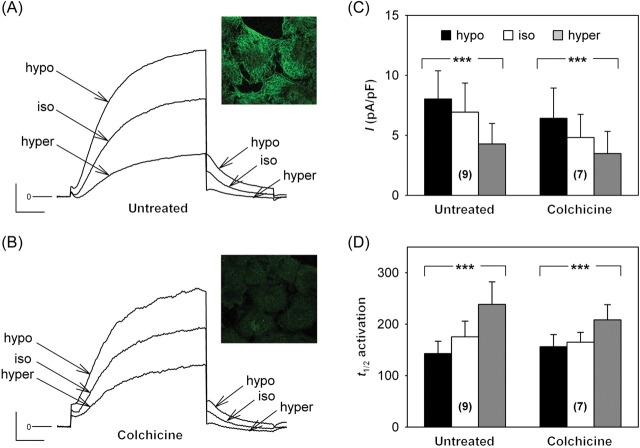

The permeabilized-patch configuration was chosen over the conventional ruptured-patch configuration to avoid run-down of KCNQ1–KCNE1 channel activity.20–22 In basal conditions, 1–2 h pretreatment with 10 µM colchicine did not modify the K+ current density measured at −40 mV after a depolarization to +40 mV (Table 1), despite microtubule depolymerization as visualized on confocal images (Figure 3A and B, insets). Neither the half-activation time used to estimate the activation kinetics, nor the deactivation time constant showed any change after colchicine treatment. Similarly, 10 µM taxol treatment neither modified the current amplitude nor its biophysical characteristics (Table 1). Microtubule alteration did not alter the channel gating or trafficking.

Table 1.

Biophysical characteristics of IKs in untreated, colchicine-, or taxol-treated COS-7 cells

| Untreated | Colchicine 10 µM | Taxol 10 µM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell number | 16–17 | 13 | 8 |

| Tail current density (pA/pF) | 8.1 ± 2.0 | 6.8 ± 1.2 | 7.3 ± 1.6 |

| t1/2 act (ms) | 163.5 ± 17.5 | 151.0 ± 15.5 | 138.4 ± 13.8 |

| τdeact (ms) | 153.4 ± 6.8 | 166.8 ± 8.6 | 154.6 ± 8.4 |

Tail current density at −40 mV; t1/2 act denotes half-activation time at +40 mV; τdeact represents deactivation time constant (single exponential fit) at −40 mV. One-way analysis of variance: non-significant for each parameter.

Figure 3.

Effects of osmotic challenge on IKs current in COS-7 cells. (A) Representative current traces recorded in a cell expressing KCNQ1–KCNE1 channels exposed to hypo-osmolar (hypo: −80 mOsm), hyper-osmolar (hyper: +80 mOsm), or iso-osmolar solution (iso). The membrane was depolarized from −80 mV to +40 mV for 1000 ms and repolarized to −40 mV for 500 ms during which the tail current was measured (scales: 100 pA and 200 ms). (B) Representative current traces from a colchicine-treated cell (10 µM) during the same voltage protocol and challenged with the same solutions (scales: 50 pA and 200 ms). Insets: β-tubulin immunostaining showing β-tubulin dilution in treated cells. Tail current density (C) and half-activation time (t1/2 activation in milliseconds; (D) measured in untreated and colchicine-treated COS-7 cells (colchicine). Untreated and colchicine-treated cells exhibited similar IKs responses to osmotic challenge [two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), non-significant for both parameters; one-way ANOVA, ***P < 0.001 for both parameters with or without treatment]. Numbers between brackets indicate the number of cells tested.

3.4. IKs response to osmotic challenge does not depend on microtubules

Although the functional link between KCNQ1 and β-tubulin did not appear under basal conditions in COS-7 cells, it may become critical for channel regulation. In ventricular myocytes, cell swelling increases the native IKs current.23,24 Interestingly, Grunnet and colleagues25 showed that an N-terminus deleted KCNQ1 (amino acid 1–95, i.e. missing part of, if not all, the KCNQ1 interacting zone with β-tubulin determined in our study) failed to respond to osmotic challenges in Xenopus oocytes. Thus, we investigated the importance of microtubular network integrity on the response of KCNQ1–KCNE1 channels to osmotic challenge in COS-7 cells. The K+ tail current, elicited by a +40 mV depolarization, increased in hypo-osmolar solution (Figure 3A and C) and decreased in hyper-osmolar solution, compared with the current recorded in iso-osmotic condition. Activation kinetics was also modified by osmolarity changes (Figure 3D). After microtubule depolymerization with colchicine, the same changes in response to osmotic shock were observed (Figure 3B–D), as in untreated cells. The deactivation kinetics was similar in all conditions (see Supplementary material online, Table S2). These data indicate that the β-tubulin interaction with KCNQ1 is not involved in current modulation by cell volume changes.

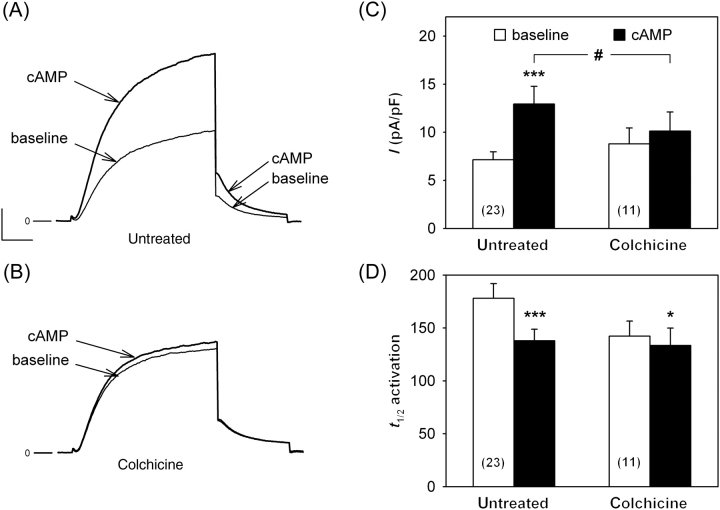

3.5. IKs response to PKA-dependent stimulation depends on microtubules

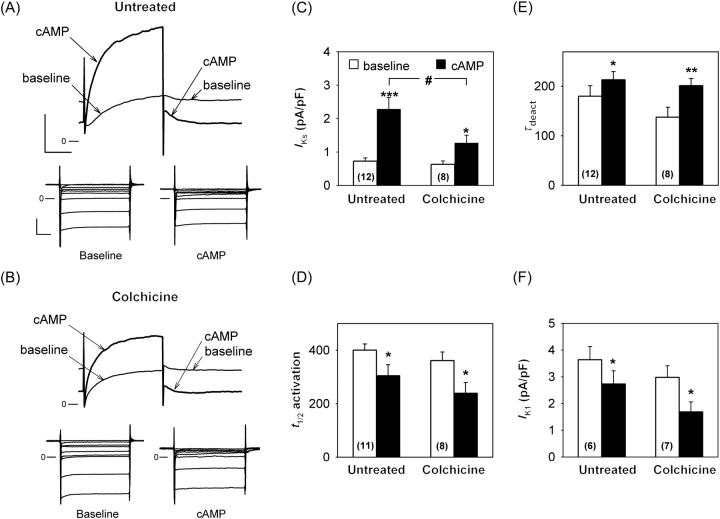

When Yotiao was cloned, it was suspected to associate with the cytoskeleton.26 Since then, Yotiao has been shown to target PKA and protein phosphatase to KCNQ1 and to be mandatory for cAMP-dependent IKs regulation.11,27 A potential role of KCNQ1–β-tubulin interaction would be that microtubules could consolidate the KCNQ1–Yotiao complex. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of microtubule depolymerization on the PKA-activated K+ current. These experiments were first conducted in COS-7 cells transfected with KCNQ1, KCNE1, and Yotiao. In this condition, the basal IKs current was not modified by colchicine (Figure 4). The density of the K+ current related to KCNQ1–KCNE1 expression was more than doubled by adding 400 µM cpt–cAMP, 10 µM forskolin, and 0.2 µM okadaic acid (Figure 4A and C). PKA stimulation of the KCNQ1–KCNE1 current was lost in the presence of colchicine (Figure 4B and C). Interestingly, the activation kinetics were significantly accelerated in both conditions by cAMP enhancement (Figure 4D), indicating that channel phosphorylation still occurs in colchicine-treated cells. The fact that only the amplitude response to PKA is altered, suggests that amplitude and activation kinetics are not linearly correlated (such as in the channel regulation by PIP221) and that an efficient coupling gives rise first to acceleration of the activation, then to an increased amplitude. Another possibility is that amplitude and activation kinetics alterations reflect distinct mechanisms (such as voltage sensing and gate opening). Nevertheless, these results suggest that microtubules are implicated in the IKs response to PKA-dependent stimulation.

Figure 4.

IKs response to protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent stimulation depends on microtubule polymerization state. Representative current traces recorded in an untreated (A) and a colchicine-treated (10 µM, B) COS-7 cells expressing KCNQ1, KCNE1, and Yotiao, in basal conditions (baseline) and exposed to 400 µM cpt–cAMP, 10 µM forskolin, and 0.2 µM okadaic acid (cAMP). Voltage protocol as in Figure 3A—scales: 100 pA and 200 ms; (B) same scales as (A). (C, D) Tail current density and half-activation time (ms) measured in untreated and colchicine-treated cells, respectively. PKA-dependent IKs response was significantly decreased in colchicine-treated cells [two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA): #P < 0.05; Tukey test: untreated: ***P < 0.001 vs. baseline value; colchicine-treated: non-significant (NS)], but the activation acceleration owing to PKA remained (two-way ANOVA: NS; t-test: untreated: ***P < 0.001 vs. baseline value; colchicine-treated: *P < 0.05). Deactivation kinetics was not altered in all conditions (see Supplementary material online, Table S2).

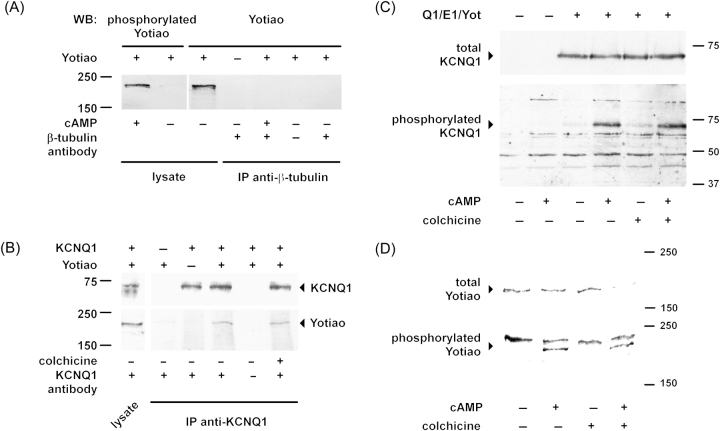

To further test the hypothesis that microtubules participate to the KCNQ1 and Yotiao connection, we checked whether Yotiao is associated with microtubules as other PKA-anchoring proteins, like AKAP7528 and MAP2B.29 As illustrated in Figure 5A, we did not observe any co-immunoprecipitation of native β-tubulin and transfected Yotiao in COS-7 cells in the absence of KCNQ1 and KCNE1 (n = 3).

Figure 5.

Microtubules interfere neither with the KCNQ1 and Yotiao interaction nor with their protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent phosphorylation. (A) Yotiao and β-tubulin do not interact in transfected COS-7 cells. Lysates of untreated cells or those exposed to 400 µM cAMP, 10 µM forskolin, and 1 µM okadaic acid, were immunoprecipitated with anti-β-tubulin antibody and the presence of Yotiao in the complex was examined by western blot. Phosphorylation efficiency was examined in lysates with anti-phosphorylated Yotiao antibody. (B) KCNQ1 interacts with Yotiao in COS-7 cells. Transfected cells were either treated or not with 10 µM colchicine for 2 h. KCNQ1 was immunoprecipitated and presence of Yotiao in the complex was examined by western blot. (C) KCNQ1 phosphorylation is not impaired by microtubule depolymerization in COS-7 cells. Western blot of cells either transfected with KCNQ1, KCNE1, and Yotiao (Q1/E1/Yot) or GFP alone, treated with 400 µM cpt–cAMP, 10 µM forskolin, and 0.2 µM okadaic acid, and probed with anti-KCNQ1 (Top) or anti-phospho-S27 KCNQ1 antibody (Bottom). The increase of phosphorylated KCNQ1 was similar in untreated and treated cells (4.4 ± 1.4-fold and 4.0 ± 1.2-fold, respectively; n = 4; Wilcoxon-signed rank test: NS). (D) Yotiao phosphorylation is not impaired by microtubule depolymerization in COS-7 cells. Western blot of cells transfected with KCNQ1, KCNE1, and Yotiao, treated with 400 µM cpt–cAMP, 10 µM forskolin, and 1 µM okadaic acid, and probed with anti-Yotiao (Top) or anti-phosphorylated Yotiao antibody (Bottom). The normalized density of the phosphorylated Yotiao-specific band was similar for untreated and treated cells (n = 4, Wilcoxon-signed rank test: NS).

One can argue that Yotiao can interact with microtubules only when phosphorylated and that this PKA-dependent association is required for subsequent IKs activation. However, we show that PKA activation leading to Yotiao phosphorylation did not induce any interaction with β-tubulin, ruling out this hypothesis (Figure 5A).

Secondly, we reasoned that if microtubules are involved in Yotiao and KCNQ1 interaction, their depolymerization should (i) limit KCNQ1 and Yotiao interaction and/or (ii) limit the channel phosphorylation. As illustrated in Figure 5B, colchicine treatment did not modify KCNQ1 and Yotiao interaction, revealed by co-immunoprecipitation in COS-7 cells (n = 3). Furthermore, KCNQ1 phosphorylation was not significantly altered (n = 4, Figure 5C).

Yotiao phosphorylation is a prerequisite for PKA-dependent activation of KCNQ1.14 Therefore, we also tested the effects of microtubule disruption on Yotiao phosphorylation. As shown in Figure 5D, colchicine treatment did not affect PKA-induced Yotiao phosphorylation (n = 4).

These results, together with the absence of β-tubulin and Yotiao co-immunoprecipitation in baseline conditions or after PKA activation, suggest that microtubules play no role in Yotiao-dependent KCNQ1 phosphorylation but modulate the influence of KCNQ1 phosphorylation on the channel activity.

Another hypothesis to explain the loss of current increase in colchicine-treated cells is that PKA stimulation recruits sub-membrane KCNQ1 pools to the membrane, as previously reported for Nav1.5,30 and microtubule depolymerization alters this trafficking. Alternatively, cAMP may decrease KCNQ1 channels endocytosis as recently reported on the potassium channel Kv1.2,31 by stabilizing the channels at the membrane. We thus tested whether the current increase observed in untreated cells was associated with an increased amount of KCNQ1 channel at the plasma membrane. COS-7 cells were transfected with the fusion protein KCNE1–KCNQ1 with a VSV extracellular tag on KCNE1 N-terminus (VSV–KCNE1–KCNQ1)12 and Yotiao. An immunoprecipitation was performed with an anti-VSV antibody on intact non-permeabilized cells. These experiments show that the amount of KCNQ1 at the plasma membrane was not increased by cAMP treatment (see Supplementary material online, Figure S1). These data suggest that KCNQ1 phosphorylation modulates the biophysical properties rather than the channel trafficking.

To evaluate the physiological relevance of the IKs regulation by microtubules, we repeated the patch-clamp experiments in guinea pig cardiomyocytes. The PKA-dependent IKs increase was significantly reduced by more than two-fold after 30 µM colchicine treatment (Figure 6B, top and C) when compared with untreated cardiomyocytes (Figure 6A, top and C), whereas activation and deactivation were similarly modified in both conditions (Figure 6D and E). Unlike IKs, the inward rectifier K+ current IK1 is decreased by PKA (Figure 6A bottom), as already reported for human and guinea pig ventricular myocytes.32,33 Here, we observed that colchicine did not alter the IK1 baseline current or its cAMP-induced decrease (Figure 6B, bottom and F). The sensitivity to microtubule depolymerization thus seems to be specific for the KCNQ1 channel.

Figure 6.

IKs and IK1 response to cAMP-dependent stimulation in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Representative IKs (Top) and IK1 (Bottom) traces recorded in untreated (A) and colchicine-treated (30 µM, B) cardiomyocytes in basal conditions (baseline) and exposed to cAMP increase (same as in Figure 4). The membrane was depolarized from −40 mV to +40 mV for 1500 ms and repolarized to −40 mV where the deactivating tail current, IKs, was measured, the remaining outward current being IK1 (A and B, scales: 200 pA and 500 ms). For IK1-specific recording, voltage steps were applied from −60 mV to various potentials from −100 to −20 mV for 500 ms (A and B scales: 500 pA and 100 ms). IKs tail current density (C), half-activation time (D), and deactivation time constant (E, single exponential fit, τdeact) in untreated and colchicine-treated cardiomyocytes. (F) IK1 current measured at the end of a 500 ms pulse from −60 mV to −40 mV, potentials at which IKs is not activated. Protein kinase A (PKA)-dependent IKs response was significantly decreased in colchicine-treated myocytes [two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA): #P < 0.05; Tukey test: untreated—**P < 0.001 vs. baseline value; colchicine-treated: *P < 0.05] despite similar activation acceleration induced by PKA (two-way ANOVA: NS; t-test—*P < 0.05, vs. corresponding baseline value) and deactivation deceleration (two-way ANOVA: NS; t-test—*P < 0.05 vs. baseline value and **P < 0.01). IK1 decrease was maintained in treated cells (two-way ANOVA: NS; t-test—*P < 0.05 vs. corresponding baseline value).

4. Discussion

In the present study, a direct interaction between β-tubulin and KCNQ1 was identified using a yeast two-hybrid screening. Both proteins are not only co-localized in cardiomyocytes, but also co-immunoprecipitate in this model and in COS-7 cells, confirming a physical association. Using patch-clamp experiments, we demonstrated that the PKA-dependent activation of IKs is modulated by microtubule polymerization in COS-7 cells and cardiomyocytes. However, microtubule disruption does not modify KCNQ1–Yotiao association and does not prevent KCNQ1 and Yotiao phosphorylation. This regulation seems to be specific to IKs, as IK1 current response to PKA activation was not modified by colchicine treatment, suggesting that IKs modulation by microtubules acts downstream the phosphorylation in the PKA signalling cascade.

Numerous and very different ion channels have been shown to be regulated by microtubules. For most of them, the role of the microtubular cytoskeleton is to regulate the protein trafficking to the appropriate cellular location.34–40 Most frequently, the identified mechanism involves a third protein [e.g. GABARAP for the neuronal GABAA receptor channel41 or mammalian diaphanous 1 (mDia1) for the mechanosensitive cation channel (PKD2) in the primary cilium of kidney cells42]. On the contrary, the Ca2+ channel TRPC1 has been demonstrated to bind directly to β-tubulin in retinal epithelium cells.43 Microtubule disruption leads to a decrease of TRPC1 expression at the plasma membrane of transfected cells. Here, we show that microtubule disruption does not modify the basal IKs amplitude or KCNQ1 targeting in COS-7 cells and in cardiomyocytes. Altogether these results rule out the involvement of tubulin in KCNQ1 trafficking.

Downstream the channel trafficking, there are several examples of channel activity modulation through tubulin polymerization. One context in which the cytoskeleton may regulate ion fluxes is volume regulation. For instance, the activity and stretch sensitivity of BKCa channels from rabbit coronary artery smooth muscle depend on microtubule stability.44 However, IKs sensitivity to osmotic changes is not dependent upon microtubule polymerization either in cardiomyocytes24 or in COS-7 cells as observed in our study.

Another way that cytoskeletal changes alter ion conductivity is by altering the efficacy of regulatory elements. It has been shown that microtubule polymerization affects L-type Ca2+ channel regulation by phosphorylation.45 However, this regulation was indirect: the authors proposed that microtubule depolymerization induces release of a guanosine triphosphate, which may lead to a maximal adenylyl cyclase activation46 and failure of β-adrenergic stimulation to further increase the Ca2+ current. The experiments presented here strongly suggest that, for KCNQ1, the participation of the microtubule network is direct: (i) We show that tubulin directly interacts with KCNQ1 and (ii) colchicine treatment spares the whole cascade down to KCNQ1 and Yotiao phosphorylation and only alters the coupling between phosphorylation and channel opening. This suggests that KCNQ1—but not a regulatory protein involved in PKA-dependent regulation (adenylyl cyclase, PKA, etc.)—is directly affected by tubulin polymerization. Furthermore, PKA stimulation does not increase KCNQ1 channel density at the membrane. This rules out the hypothesis of an altered channel trafficking after microtubule depolymerization that would prevent PKA-mediated IKs increase. Altogether, our data suggest that the current response alteration is caused by a weaker coupling of the channel phosphorylation and its intrinsic activation.

Previous studies showed that the IKs current response to PKA-dependent stimulation does not only depend on KCNQ1 channel phosphorylation, but also on Yotiao integrity. Indeed, the amplitude of the pseudo-phosphorylated form of the KCNQ1 channel (S27D KCNQ1) is increased only in the presence of Yotiao.13 In this case, the AKAP Yotiao seems to be required for the post-phosphorylation response. Furthermore, phosphorylation of Yotiao itself by PKA is needed to observe any IKs increase. In CHO cells, the unphosphorylable S43A Yotiao mutant prevents an IKs increase despite the conserved KCNQ1 phosphorylation when PKA is activated.14 In addition to ours, these results indicate that both Yotiao phosphorylation and microtubule integrity are required to maintain the PKA-dependent channel phosphorylation and activation coupling. However, these two factors seem independent because co-immunoprecipitation experiments failed to show any interaction between Yotiao and tubulin.

The duration of the action potential repolarization is known to be heterogeneous across the human ventricular wall. A longer action potential is recorded in cells from the mid-myocardium (M cells).47 Using different animal models, this difference has been shown to be owing to a smaller IKs in M cells.48,49 We have previously shown that the action potential prolongation in human M cells is correlated to higher expression of the dominant-negative alternative isoform of KCNQ1 that results in a smaller IKs.50 IKs plays a major role in human ventricular repolarization mostly under sympathetic stimulation and when the repolarization reserve is reduced.6 Therefore, a change in IKs sensitivity to β1-adrenergic stimulation, when microtubules are altered in pathological conditions, may appear to be highly relevant for ventricular repolarization and induction of arrhythmias, in particular, by inducing transmural dispersion alterations.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Cardiovascular Research online.

Funding

Supported by grants from the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale (Inserm), from the Agence Nationale de Recherche to IB (ANR COD/A05045GS) and GL (ANR -05-JCJC-0160-01), from the Fondation de la Recherche Médicale to IB, and from Vaincre la Mucoviscidose to JM. CSN is financially supported by the Inserm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the expert technical assistance of Béatrice Leray, Marie-Jo Louérat and Agnes Carcouët and of Caroline Colombeix and Philippe Hulin from the Cell Imaging platform of the Institut Fédératif de Recherche of Nantes (IFR26) and Cécile Terrenoire for her helpful advices.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1.Wang Q, Curran ME, Splawski I, Burn TC, Millholland JM, VanRaay TJ, et al. Positional cloning of a novel potassium channel gene: KvLQT1 mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias. Nat Genet. 1996;12:17–23. doi: 10.1038/ng0196-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang WP, Levesque PC, Little WA, Conder ML, Shalaby FY, Blanar MA. KvLQT1, a voltage-gated potassium channel responsible for human cardiac arrhythmias. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:4017–4021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melman YF, Krummerman A, McDonald TV. KCNE regulation of KvLQT1 channels: structure-function correlates. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2002;12:182–187. doi: 10.1016/s1050-1738(02)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barhanin J, Lesage F, Guillemare E, Fink M, Lazdunski M, Romey G. KvLQT1 and lsK (minK) proteins associate to form the IKs cardiac potassium current. Nature. 1996;384:78–80. doi: 10.1038/384078a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanguinetti MC, Curran ME, Zou A, Shen J, Spector PS, Atkinson DL, et al. Coassembly of KvLQT1 and minK (IsK) proteins to form cardiac IKs potassium channel. Nature. 1996;384:80–83. doi: 10.1038/384080a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jost N, Virag L, Bitay M, Takacs J, Lengyel C, Biliczki P, et al. Restricting excessive cardiac action potential and QT prolongation: a vital role for IKs in human ventricular muscle. Circulation. 2005;112:1392–1399. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.550111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levitan IB. Modulation of ion channels in neurons and other cells. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1988;11:119–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.11.030188.001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown D, Katsura T, Gustafson CE. Cellular mechanisms of aquaporin trafficking. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:F328–F331. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.275.3.F328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotin D, Kanelis V, Schild L. Trafficking and cell surface stability of ENaC. Am J Physiol. 2001;281:F391–F399. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.281.3.F391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furukawa T, Ono Y, Tsuchiya H, Katayama Y, Bang ML, Labeit D, et al. Specific interaction of the potassium channel beta-subunit minK with the sarcomeric protein T-cap suggests a T-tubule-myofibril linking system. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:775–784. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potet F, Scott JD, Mohammad-Panah R, Escande D, Baró I. AKAP proteins anchor cAMP-dependent protein kinase to KvLQT1/IsK channel complex. Am J Physiol. 2001;280:H2038–H2045. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.5.H2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marx SO, Kurokawa J, Reiken S, Motoike H, D'Armiento J, Marks AR, et al. Requirement of a macromolecular signaling complex for β-adrenergic receptor modulation of the KCNQ1-KCNE1 potassium channel. Science. 2002;295:496–499. doi: 10.1126/science.1066843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kurokawa J, Motoike HK, Rao J, Kass RS. Regulatory actions of the A-kinase anchoring protein Yotiao on a heart potassium channel downstream of PKA phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16374–16378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405583101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen L, Kurokawa J, Kass RS. Phosphorylation of the A-kinase-anchoring protein Yotiao contributes to protein kinase A regulation of a heart potassium channel. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31347–31352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505191200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meluh PB, Rose MD. KAR3, a kinesin-related gene required for yeast nuclear fusion. Cell. 1990;60:1029–1041. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90351-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vojtek AB, Hollenberg SM, Cooper JA. Mammalian Ras interacts directly with the serine/threonine kinase Raf. Cell. 1993;74:205–214. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90307-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurokawa J, Chen L, Kass RS. Requirement of subunit expression for cAMP-mediated regulation of a heart potassium channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2122–2127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0434935100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demolombe S, Baró I, Péréon Y, Bliek J, Mohammad-Panah R, Pollard H, et al. A dominant negative isoform of the long QT syndrome 1 gene product. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6837–6843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costes SV, Daelemans D, Cho EH, Dobbin Z, Pavlakis G, Lockett S. Automatic and quantitative measurement of protein-protein colocalization in live cells. Biophys J. 2004;86:3993–4003. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.038422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marcus DC, Shen Z. Slowly activating voltage-dependent K+ conductance is apical pathway for K+ secretion in vestibular dark cells. Am J Physiol. 1994;267:C857–C864. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.3.C857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loussouarn G, Park KH, Bellocq C, Baró I, Charpentier F, Escande D. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, PIP2, controls KCNQ1/KCNE1 voltage-gated potassium channels: a functional homology between voltage-gated and inward rectifier K+ channels. EMBO J. 2003;22:5412–5421. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loussouarn G, Baró I, Escande D. KCNQ1 K+ channel-mediated cardiac channelopathies. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;337:167–183. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-095-2:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rees SA, Vandenberg JI, Wright AR, Yoshida A, Powell T. Cell swelling has differential effects on the rapid and slow components of delayed rectifier potassium current in guinea pig cardiac myocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1995;106:1151–1170. doi: 10.1085/jgp.106.6.1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Z, Mitsuiye T, Noma A. Cell distension-induced increase of the delayed rectifier K+ current in guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1996;78:466–464. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.3.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grunnet M, Jespersen T, MacAulay N, Jorgensen NK, Schmitt N, Pongs O, et al. KCNQ1 channels sense small changes in cell volume. J Physiol. 2003;549:419–427. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.038455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin JW, Wyszynski M, Madhavan R, Sealock R, Kim JU, Sheng M. Yotiao, a novel protein of neuromuscular junction and brain that interacts with specific splice variants of NMDA receptor subunit NR1. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2017–2027. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02017.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurokawa J, Motoike HK, Rao J, Kass RS. Regulatory actions of the A-kinase anchoring protein Yotiao on a heart potassium channel downstream of PKA phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:16374–16378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405583101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glantz SB, Li Y, Rubin CS. Characterization of distinct tethering and intracellular targeting domains in AKAP75, a protein that links cAMP-dependent protein kinase II beta to the cytoskeleton. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12796–12804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davare MA, Dong F, Rubin CS, Hell JW. The A-kinase anchor protein MAP2B and cAMP-dependent protein kinase are associated with class C L-type calcium channels in neurons. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30280–30287. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.30280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallaq H, Yang Z, Viswanathan PC, Fukuda K, Shen W, Wang DW, et al. Quantitation of protein kinase A-mediated trafficking of cardiac sodium channels in living cells. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;72:250–261. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connors EC, Ballif BA, Morielli AD. Homeostatic regulation of Kv1.2 potassium channel trafficking by cyclic AMP. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3445–3453. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708875200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koumi S, Backer CL, Arentzen CE, Sato R. β-Adrenergic modulation of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel in isolated human ventricular myocytes. Alteration in channel response to β-adrenergic stimulation in failing human hearts. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2870–2881. doi: 10.1172/JCI118358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koumi S, Wasserstrom JA, Ten Eick RE. β-adrenergic and cholinergic modulation of inward rectifier K+ channel function and phosphorylation in guinea-pig ventricle. J Physiol. 1995;486:661–678. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp020842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tousson A, Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Apical recruitment of CFTR in T-84 cells is dependent on cAMP and microtubules but not Ca2+ or microfilaments. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1325–1334. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.6.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shimoni Y, Ewart HS, Severson D. Insulin stimulation of rat ventricular K+ currents depends on the integrity of the cytoskeleton. J Physiol. 1999;514:735–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.735ad.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Garcia F, Kierbel A, Larocca MC, Gradilone SA, Splinter P, LaRusso NF, et al. The water channel aquaporin-8 is mainly intracellular in rat hepatocytes, and its plasma membrane insertion is stimulated by cyclic AMP. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12147–12152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kilic G, Doctor RB, Fitz JG. Insulin stimulates membrane conductance in a liver cell line: evidence for insertion of ion channels through a phosphoinositide 3-kinase-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:26762–26768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moral Z, Dong K, Wei Y, Sterling H, Deng H, Ali S, et al. Regulation of ROMK1 channels by protein-tyrosine kinase and -tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:7156–7163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008671200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ameen NA, Marino C, Salas PJ. cAMP-dependent exocytosis and vesicle traffic regulate CFTR and fluid transport in rat jejunum in vivo. Am J Physiol. 2003;284:C429–C438. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00261.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choquet D, Triller A. The role of receptor diffusion in the organization of the postsynaptic membrane. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:251–265. doi: 10.1038/nrn1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang H, Bedford FK, Brandon NJ, Moss SJ, Olsen RW. GABA(A)-receptor-associated protein links GABA(A) receptors and the cytoskeleton. Nature. 1999;397:69–72. doi: 10.1038/16264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rundle DR, Gorbsky G, Tsiokas L. PKD2 interacts and co-localizes with mDia1 to mitotic spindles of dividing cells: role of mDia1 IN PKD2 localization to mitotic spindles. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:29728–29739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bollimuntha S, Cornatzer E, Singh BB. Plasma membrane localization and function of TRPC1 is dependent on its interaction with beta-tubulin in retinal epithelium cells. Vis Neurosci. 2005;22:163–170. doi: 10.1017/S0952523805222058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piao L, Ho WK, Earm YE. Actin filaments regulate the stretch sensitivity of large-conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels in coronary artery smooth muscle cells. Pflügers Arch. 2003;446:523–528. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1079-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomez AM, Kerfant BG, Vassort G. Microtubule disruption modulates Ca2+ signaling in rat cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2000;86:30–36. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hatta S, Ozawa H, Saito T, Amemiya N, Ohshika H. Tubulin stimulates adenylyl cyclase activity in rat striatal membranes via transfer of guanine nucleotide to Gs protein. Brain Res. 1995;704:23–30. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drouin E, Charpentier F, Gauthier C, Laurent K, Le Marec H. Electrophysiologic characteristics of cells spanning the left ventricle wall of human heart: evidence for presence of M cells. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00167-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu DW, Antzelevitch C. Characteristics of the delayed rectifier current (IKr and IKs) in canine ventricular epicardial, midmyocardial, and endocardial myocytes. A weaker IKs contributes to the longer action potential of the M cell. Circ Res. 1995;76:351–365. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.3.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Main MC, Bryant SM, Hart G. Regional differences in action potential characteristics and membrane currents of guinea-pig left ventricular myocytes. Exp Physiol. 1998;83:747–761. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1998.sp004156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Péréon Y, Demolombe S, Baró I, Drouin E, Charpentier F, Escande D. Differential expression of KvLQT1 isoforms across the human ventricular wall. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:H1908–H1915. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.6.H1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.