Abstract

Motivation: The power of a microarray experiment derives from the identification of genes differentially regulated across biological conditions. To date, differential regulation is most often taken to mean differential expression, and a number of useful methods for identifying differentially expressed (DE) genes or gene sets are available. However, such methods are not able to identify many relevant classes of differentially regulated genes. One important example concerns differentially co-expressed (DC) genes.

Results: We propose an approach, gene set co-expression analysis (GSCA), to identify DC gene sets. The GSCA approach provides a false discovery rate controlled list of interesting gene sets, does not require that genes be highly correlated in at least one biological condition and is readily applied to data from individual or multiple experiments, as we demonstrate using data from studies of lung cancer and diabetes.

Availability: The GSCA approach is implemented in R and available at www.biostat.wisc.edu/∼kendzior/GSCA/.

Contact: kendzior@biostat.wisc.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

A main goal of microarray experiments is to identify individual genes or gene sets differentially regulated across biological conditions. Most often, differential regulation is taken to mean differential expression; and a number of statistical methods for identifying differentially expressed (DE) genes or gene sets are now available (for reviews, see Allison et al., 2006; Barry et al., 2008; Ho et al., 2007; Newton et al., 2007). Although useful in thousands of studies, these methods are not able to identify many important classes of differentially regulated genes. One example concerns differentially co-expressed (DC) genes.

Two genes are DC if their correlation in one biological condition differs from that in another; and statistical methods for identifying DC gene pairs are available (Lai et al., 2004; Shedden and Taylor, 2005). Generally speaking, a DC gene group is defined similarly, as one in which the correlation structure among the group's genes in one condition differs from that in another. However, the exact way in which one defines the gene group, specifies the correlation structure, and quantifies differences varies from study to study.

A number of investigators have proposed approaches that identify groups of genes where pairwise correlations are necessarily high in at least one biological condition (Brown et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2005; Ihmels et al., 2005; Kostka and Spang, 2004; Oldham et al., 2006; Watson, 2006). Most of the methods begin by identifying modules (Oldham et al., 2006), clusters (Brown et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2005; Ihmels et al., 2005; Watson, 2006) or cliques (Voy et al., 2006) within biological condition followed by a comparison of the condition-specific lists. Those modules, clusters or cliques identified in one condition but not another are of primary interest and often investigated further to determine if there is evidence of enrichment of biological function(s) potentially associated with the underlying mechanisms giving rise to the DC.

In this work, we propose a statistical approach to identify DC gene groups. Unlike previous work, our approach does not require that genes within a set are highly correlated in at least one biological condition; they may be, but differential regulation can manifest itself in significant but more subtle correlation shifts. Furthermore, the approach provides a false discovery rate (FDR) controlled list of interesting groups, and is readily applied to data from individual or multiple experiments. As detailed in Section 2, the approach requires that gene groups be defined a priori. We consider groups, referred to hereinafter as gene sets, specified by Gene Ontology (GO; The Gene Ontology Consortium, 2000) and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG; Kanehisa and Goto, 2000), noting that other annotations or study-specific biological knowledge could also be used. Pairwise co-expressions (correlations) are calculated for all gene pairs within a gene set; and a dispersion index is introduced to quantify the difference between the resulting gene set co-expression vectors. This gene set co-expression analysis (GSCA) is illustrated in the context of a single experiment in Section 2.1; applications to multiple experiments are provided in Section 2.2. Once DC gene sets are obtained, it is often of interest to identify the specific genes within each gene set contributing most to the observed DC. A statistical test for identifying DC hub genes, or genes with unusually high contributions, is given in Section 2.3. A small simulation study and results from analyses of lung cancer and diabetes datasets are given in Sections 3 and 4, respectively. Section 5 concludes with a discussion of the advantages and disadvantages of the GSCA approach, and the similarities and differences to the well-known gene set enrichment methods.

2 METHODS

The GSCA approach begins with a collection of gene sets. These can be defined from GO, KEGG or some other biological knowledge. Of primary interest is the identification of those gene sets significantly DC across biological conditions.

2.1 Identification of DC gene sets within a single experiment

Consider first a single two group microarray experiment. To assess the extent of DC for a given gene set c with nc genes, pairwise co-expressions (correlations) are calculated for all  gene pairs, and a dispersion index is applied to the co-expression vectors to quantify the extent of DC. A schematic is given in Figure 1.

gene pairs, and a dispersion index is applied to the co-expression vectors to quantify the extent of DC. A schematic is given in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the GSCA approach. Shown are expression matrices for a single gene set with nc genes in two biological conditions, T1 and T2; Nk represents the number of arrays in condition k, k = 1, 2.

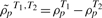

The dispersion index for a single study GSCA, DS, is given by the Euclidean distance, adjusted for the size of the gene set considered:

| (1) |

where  ,

,  indexes gene pairs within the gene set c of size nc, and ρpTk denotes the co-expression calculated for gene pair p within condition Tk, k = 1, 2. For a study with more than two conditions, DS is averaged across study pairs.

indexes gene pairs within the gene set c of size nc, and ρpTk denotes the co-expression calculated for gene pair p within condition Tk, k = 1, 2. For a study with more than two conditions, DS is averaged across study pairs.

To identify significant DC gene sets, samples are permuted across conditions to simulate the null of equivalent correlation between conditions. The GSCA approach shown in Figure 1 is applied to calculate a DC score from the permuted dataset. This is repeated on B − 1 permuted datasets to yield gene set-specific P-values. For example, for gene set c, the permutation P-value is  , where T1b and T2b denote samples derived from the b-th permuted dataset. An estimated FDR is obtained by converting the P-values to q-values (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003). In our simulations and case studies, we considered Pearson's correlation coefficients and B = 10 000.

, where T1b and T2b denote samples derived from the b-th permuted dataset. An estimated FDR is obtained by converting the P-values to q-values (Storey and Tibshirani, 2003). In our simulations and case studies, we considered Pearson's correlation coefficients and B = 10 000.

2.2 Identification of DC gene sets across multiple experiments

The GSCA approach can combine evidence from multiple experiments to identify DC gene sets. We refer to this as a meta-GSCA. As different experiments use different microarray platforms that often contain different sets of genes and gene identifiers, the problem of gene matching—identifying the genes in common across studies—must be addressed prior to meta-GSCA. Gene matching is generally done by specifying a gene identifier common to all experiments, matching on those identifiers, and then removing genes that are not represented across all experiments. In addition to gene matching, it is also necessary to summarize transcript-level expression which is often measured using multiple probes. Common methods include taking the brightest probe (Mah et al., 2004; Subramanian et al., 2005), the most variant probe (Dallas et al., 2005; Raghavan et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2007) or the average across the probes (Lee et al., 2008; Parmigiani et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2007). We use the average taken at the log level.

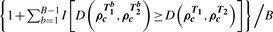

Once a set of common genes is identified, gene sets are defined for the common genes and meta-GSCA proceeds similarly to that above, with a few important differences. First, in single study GSCA, it is of primary interest to identify those gene sets with large differences in correlation between conditions. This is also important in the meta-GSCA, but equally important in preservation of the difference across studies. In other words, for a meta-GSCA combining two studies S1 and S2, we would like to identify DC gene sets for which the difference in co-expressions within S1,  , is close to the co-expression differences in S2,

, is close to the co-expression differences in S2,  . We use a test statistic similar to (1), where

. We use a test statistic similar to (1), where  is replaced by

is replaced by  for the two-study case:

for the two-study case:

| (2) |

where  represents the sign of the correlation for gene pair p in condition Tk, k = 1, 2. For studies with more than two conditions, DM is averaged across study pairs.

represents the sign of the correlation for gene pair p in condition Tk, k = 1, 2. For studies with more than two conditions, DM is averaged across study pairs.

Unlike the single study GSCA, the gene sets that are most interesting in the meta-GSCA are those with unusually small values of the statistic given by (2), as these are the sets that are most highly preserved across studies. Note that gene sets containing many uncorrelated genes could appear to be highly preserved, even if they are not, if ρp is used as in (1). This is because observed correlations for such sets would most often be near zero and, as a result, the differences in correlations between studies would be necessarily small. By considering s(ρp) instead of ρp, Equation (2) helps to ensure that such sets are not identified. As in the single study GSCA, permutations are used to calibrate the statistic given by (2). However, in the meta-GSCA case, the null is that  differs from

differs from  . Permuting samples within each study across conditions results in preservation of

. Permuting samples within each study across conditions results in preservation of  across studies since the values of

across studies since the values of  within each study Sk will be near zero. In other words, permuting samples across conditions as in a single study GSCA breaks the DC structure which simulates the alternative, not the null. Instead, we permute gene pairs within study across gene sets keeping the gene set sizes fixed (see Supplementary Fig. S1). This preserves the overall amount of DC, but breaks the relationship among gene pairs across studies.

within each study Sk will be near zero. In other words, permuting samples across conditions as in a single study GSCA breaks the DC structure which simulates the alternative, not the null. Instead, we permute gene pairs within study across gene sets keeping the gene set sizes fixed (see Supplementary Fig. S1). This preserves the overall amount of DC, but breaks the relationship among gene pairs across studies.

2.3 Identification of DC hub genes

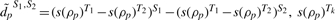

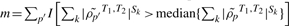

Given DC gene sets obtained from a single study or meta-GSCA, it is often of interest to identify specific genes within the gene sets that contribute most to the detected DC. Consider a gene g within gene set c. For K studies, a simple ordering ranks g according to the average DC,  , where k indexes study and p′ indexes the nc − 1 gene pairs containing g. A complementary approach that is less sensitive to outliers considers the number of gene pairs containing g with co-expression differences that exceed the median of all co-expressions in c (co-expressions are averaged across studies in the case of multiple studies). In other words, we consider

, where k indexes study and p′ indexes the nc − 1 gene pairs containing g. A complementary approach that is less sensitive to outliers considers the number of gene pairs containing g with co-expression differences that exceed the median of all co-expressions in c (co-expressions are averaged across studies in the case of multiple studies). In other words, we consider  where p indexes the Pc gene pairs within gene set c, as in (1). A hypergeometric distribution can be used to calculate the probability that j of nc − 1 gene pairs chosen from Pc gene pairs exceed the median absolute correlation of the Pc pairs. Gene-specific P-values are obtained from the hypergeometric test given in (3) and adjusted using a Bonferroni correction for nc, the total number of genes in the set:

where p indexes the Pc gene pairs within gene set c, as in (1). A hypergeometric distribution can be used to calculate the probability that j of nc − 1 gene pairs chosen from Pc gene pairs exceed the median absolute correlation of the Pc pairs. Gene-specific P-values are obtained from the hypergeometric test given in (3) and adjusted using a Bonferroni correction for nc, the total number of genes in the set:

| (3) |

where  . When Pc is odd, (Pc − 1)/2 and (Pc + 1)/2 are used for the left and right Pc/2, respectively, in the numerator. Genes with significant Bonferroni corrected hypergeometric P-values are referred to as hub genes.

. When Pc is odd, (Pc − 1)/2 and (Pc + 1)/2 are used for the left and right Pc/2, respectively, in the numerator. Genes with significant Bonferroni corrected hypergeometric P-values are referred to as hub genes.

2.4 Comparison to tests for enrichment

Generally speaking, most methods to detect enrichment take one of two approaches [Newton et al. (2007) and Sartor et al.. (2009) provide detailed reviews and comparisons of enrichment methods]. The first consists of identifying DE genes (or genes otherwise significantly associated with a response), and then evaluating gene sets for which there are more DE genes than expected by chance. Evaluation proceeds through a hypergeometric test, or something similar (Falcon and Gentleman, 2007). A second enrichment approach considers all genes (not just DE genes) and identifies gene sets for which a set-level statistic looks unusual compared with the same statistic evaluated following label permutations. Details of this type of approach are given in Subramanian et al. (2005), who proposed the gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), and Barry et al. (2005), who proposed a framework for the significance analysis of function and expression (SAFE). The single study GSCA approach is most similar to GSEA (or SAFE) in that a single statistic is calculated for each gene set and calibrated via permutations across samples. The results of single study GSCA are therefore compared with GSEA in Section 4.1. We also compare the single study GSCA results to those obtained by testing for enrichment among DC gene pairs. In short, we evaluate condition-specific co-expression for all gene pairs in a dataset, identify those pairs that are DE between conditions, and test for enrichment using a hypergeometric test as in Falcon and Gentleman (2007). As each gene pair has a single co-expression value within a given condition (i.e. replicate measurements for a pair of genes determine a single co-expression value), the DE analysis is carried out using EBarrays, an empirical Bayes approach that shares information across genes (or in this case gene pairs) and can therefore be applied when replicate measurements are not available (Newton et al., 2001). Because the GSEA approach does not extend naturally to multiple studies, meta-GSCA is compared with an alternative approach. Specifically, we consider the two most common DE meta-analysis methods, Rhodes et al. (2002) and Choi et al. (2003), to provide lists of DE genes. The lists are then tested for enrichment using the hypergeometric approach described in Falcon and Gentleman (2007).

3 SIMULATION STUDY

To assess the performance of the GSCA approach, we performed two small sets of simulations. The simulations are in no way designed to capture many of the subtle complexities inherent in microarray-based co-expression, but rather to provide some preliminary information on operating characteristics of the GSCA approach in simple settings. For both sets of simulations, we considered 20 replicate measurements in each of two conditions. Log measurements for genes in a given gene set in condition 1 (condition 2) are simulated as multivariate normal with mean vector zero and covariance matrix Σ1 (Σ2). Σ1 is generated as in Schäfer and Strimmer (2004). Briefly, for a gene set of size nc, we start with an nc × nc matrix of zeros. Off-diagonal positions in the upper triangular portion of the matrix are filled in with random draws from a uniform distribution between −1 and 1. The lower triangular portion is filled in to create a symmetric matrix. Column sums are computed from the absolute values of matrix entries, and the corresponding diagonal element is set to the sum plus a small constant (here 0.0001). This ensures that the resulting matrix is diagonally dominant and therefore positive definite. For both sets of simulations, we considered 1000 gene sets, 250 of sizes 3, 5, 10 and 20; 10% (25 sets) of each size are defined to be DC. For equivalently co-expressed gene sets, Σ2 is defined to equal Σ1. In the first set of simulations, Σ2 for a DC gene set is constructed as follows: each (i, j)-th entry (i ≠ j) of Σ2 is defined as the negative of the (i, j)-th entry from Σ1. In this case, each gene pair in a gene set is DC, although we note that for any given pair, the magnitude of the change may be quite small (e.g. from 0.02 to −0.02). In the second set of simulations, the proportion of DC gene pairs varies from 10% to 50%. Specifically, we construct five sets each with 10%, 20%, 30%, 40% and 50% of the (i, j)-th entries changing sign between Σ1 and Σ2. The upper panel of Supplementary Figure S2 shows that test statistics calculated from simulated data are close to those observed in the Harvard lung cancer data described in the next section. The middle and lower panels show that FDR is well controlled and power increases with the amount of DC, as expected. In contrast, an enrichment analysis on DC gene pairs found no gene sets with FDR <25% for either set of simulations.

4 RESULTS

4.1 Lung cancer

We illustrate the GSCA approach using the three lung cancer microarray datasets considered in Parmigiani et al. (2004) and Subramanian et al. (2005) and described in detail in Garber et al. (2001), Bhattacharjee et al. (2001) and Beer et al. (2002). Briefly, the three studies referred to here as the Stanford (Garber et al., 2001), Harvard (Bhattacharjee et al., 2001) and Michigan studies (Beer et al., 2002), were aimed at characterizing lung tumor gene expression profiles relative to that of normal lung tissue. The Stanford and Harvard studies include many subtypes of lung cancer, while the Michigan study focuses on lung adenocarcinomas, a tumor subtype included in the other two studies. The Harvard, Michigan and Stanford studies contain 17, 10, 5 normals and 139, 86, 41 tumor samples, respectively.

We considered the Entrez Gene ID, Unigene ID and Gene Symbol for gene matching. The Entrez Gene IDs were used as this ID gave the biggest inter-study gene coverage overlap for the lung cancer data. Following gene matching, the 3924 genes that appeared in all three studies were annotated into 3649 gene sets including 3471 GO categories and 178 KEGG pathways of at least size 3. We note that GSCA conducted within each study would not require any gene matching; however, gene matching was done here prior to all analyses to facilitate comparison of the GSCA results with the meta-GSCA results that follow.

The GSCA approach was applied to each of the three studies in isolation. Table 1 shows the total number of DC gene sets identified within each study at varying levels of FDR. Given the dispersion index specified in (1), the identification of a given set as DC could be due to a small number of gene pairs showing large differences in correlation between conditions, to many gene pairs showing moderate difference, or both. As a result it is useful to further investigate the identified gene sets to gain insight into specific sources of DC.

Table 1.

Number of significant DC gene sets (total 3649)

| FDR (%) | Harvard | Michigan | Stanford | H&M | All three |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 312 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 1663 | 1582 | 0 | 947 | 0 |

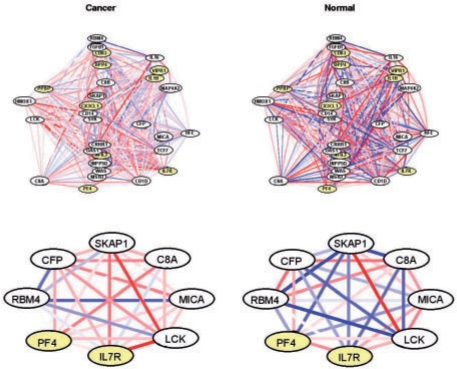

Consider a particular gene set, the immune response gene set GO:0006955, which was identified as DC at FDR 4.2% using the Harvard study data. To focus on a subset of the 211 genes in this set, genes were rank ordered by P-values derived from the hypergeometric test described in (3). The 30 genes with smallest P-values are shown in the upper panel of Figure 2. A striking feature concerns the presence of relatively stronger co-expressions in the normal condition. A closer look at a subset of the network (lower panel) highlights a few specific differences. For example, the co-expression between CFP and SKAP1 increases in cancer compared with normal; the opposite holds for CFP and RBM4. CFP, complement factor properdin, is a member of the properdin family which is known to play an important role in the immune system (Ivanovska et al., 2008; Stover et al., 2008) and has been associated with numerous types of cancer (Rottino et al., 2006).

Fig. 2.

GO:0006955 immune response. The upper (lower) panel shows the 30 (8) genes most DC between cancer and normal. Edges represent co-expressions ranging from −1 (blue) to 1 (red). Nodes identified as DE by Rhodes et al. (2002) or Choi et al. (2003) are shaded.

Similar results are observed in the Michigan and Stanford studies (see Supplementary Fig. S3), although this gene set did not reach the same level of statistical significance. Using the Michigan data, the gene set is identified as DC at FDR 8.3%. With the Stanford data, the estimated FDR for this gene set is 49%, which is clearly quite high. However, we note that 0.49 was the smallest q-value observed in the Stanford DC analysis, largely due to the relatively small sample size.

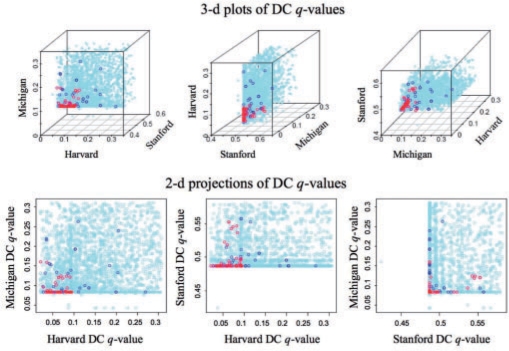

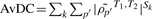

When the data are combined in a meta-GSCA, the immune response gene set GO:0006955 as well as a number of others (48 at 5% FDR, shown in Supplementary Table S1) is identified as significantly DC. As in the case of GO:0006955, the sets identified in the meta-GSCA are largely those showing moderate, but not necessarily statistically significant evidence of DC within each study. This is shown in Figure 3, where the study-specific GSCA q-values are plotted for each study, and color-coded according to the meta-GSCA q-values. As shown, most of the gene sets identified as statistically significant in the meta-GSCA are those having relatively small (although not necessarily significant) study-specific q-values.

Fig. 3.

Study specific GSCA q-values are shown for the 3649 gene sets (upper panels show varying angles of the 3D plot). Red, blue and light blue values correspond to gene sets for which the meta-GSCA q-values are q < 0.1, 0.1 ≤ q < 0.3 and q ≥ 0.3, respectively.

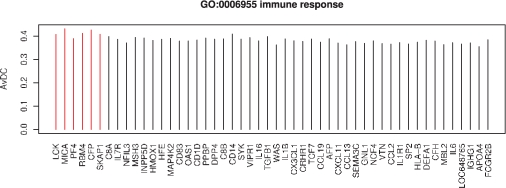

Figure 4 displays the gene-specific average DCs for 50 of the 211 genes in GO category GO:0006955, rank ordered by the hub-gene test described in Section 2.3. The most significant hub gene identified in this set is LCK, lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase, a much studied gene that is associated with lung and other kinds of cancer (Harashima et al., 2001; Imai et al., 2001; Krystal et al., 1998; Naito et al., 2007). Slow decay of the average DCs as shown suggests that there is not a single gene, or a few genes, driving the DC call for this dataset, but rather many genes showing a similar amount of DC overall. Investigation of such plots can be useful when identifying DC gene sets for which there are a few genes giving rise to a majority of the observed DC.

Fig. 4.

The average DC between two biological conditions is shown for 50 of the 211 genes in GO:0006955. The genes are ordered by P-values obtained from a hub-gene test (see Section 2.3). Red bars highlight genes with Bonferroni corrected P <0.05.

A similar calculation was carried out for each of the 48 gene sets identified in the meta-GSCA. The top 10 hub genes (10 genes with smallest hub-gene test P-values) were recorded for each set and the 12 genes showing up at least five times in the top 10 across the 48 sets are shown in Table 2. There we give the gene name and the number of sets (out of 48) for which that gene is in the top 10 hub-gene list. As genes present in many gene sets are favored for over representation, we also report the number of sets (out of 48) that the gene appears in, the number of genes that appear in that many sets and the number of genes that appear in at least that many sets. For example, MXI1 appears in the top 10 genes in 10 of 48 gene sets. It is present in 11 of the 48 gene sets; 92 other genes are present in exactly 11 of the 48 gene sets; and 314 genes are present in 11 or more of the 48 gene sets. MXI1 is a well-known tumor suppressor gene (Ariyanayagam-Baksh et al., 2003; Eagle et al., 1995; Kim et al., 1998; Petersen et al., 1998), and has recently been studied with respect to its interactions with other genes (Corn and El-Deiry, 2007; Dang et al., 2008; Dooley et al., 1995; Tsao et al., 2008). A number of other interesting genes made the list, including TGFB1 which has been associated with lung cancer risk (Park et al., 2006), and BMP7, a gene recently identified as a potential therapeutic target for breast cancer (Yan and Chen, 2007) and metastatic bone disease (Buijs et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Common hub genes identified in 48 gene sets

| Gene name | Top 10 | GS | O-GS | O-A-GS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MXI1 | 10 | 11 | 92 | 314 |

| FADS1 | 10 | 10 | 113 | 427 |

| RBM4 | 9 | 9 | 165 | 592 |

| TGFB1 | 8 | 30 | 1 | 1 |

| BMP7 | 8 | 9 | 165 | 592 |

| MICA | 7 | 10 | 113 | 427 |

| CFP | 7 | 10 | 113 | 427 |

| FEZ1 | 7 | 7 | 258 | 1064 |

| CLOCK | 7 | 7 | 258 | 1064 |

Shown are the gene name, the number of times (out of 48) the gene appears in the top 10 hub-gene list (Top 10), the number of gene sets (out of 48) containing that gene (GS), the number of other genes that appear in GS gene sets (O-GS), and the number of other genes that appear in at least GS gene sets (O-A-GS).

We note that the results discussed here are largely distinct from those obtained from traditional enrichment methods (for details on the enrichment methods employed here, see Section 2.4). GSEA applied to the Harvard data found no gene sets to be enriched for DE genes at FDR 5% (or 10% FDR; the smallest q-value from the GSEA analysis was 0.18). The upper left panel of Supplementary Figure S4 suggests that most of the gene sets show little DE between tumor and normal. That is not the case for DC (upper right panel of Fig. S4). Tests for enrichment among DC gene pairs gave analogous results with only eight gene sets identified at 5% FDR, compared with 312 gene sets identified by GSCA (Table 1). Two of the eight are represented in the 312; all eight are represented in the 1663 sets identified by GSCA at FDR 10%. A similar finding was observed in the meta-analysis. Rhodes et al. (2002) and Choi et al. (2003) identified 111 and 1534 of the 3924 genes to be DE at FDR 5%, with each of the 111 genes contained in 1534. The GO category GO:0006955 highlighted in Figure 2 contained five genes identified as DE using the method of Rhodes et al. (2002); the method of Choi et al. (2003) identified 86 DE genes. Given these totals, GO:0006955 was not found to be enriched for DE genes using the hypergeometric approach described in Falcon and Gentleman (2007) at FDR 5%. Indeed, neither the DE list derived from Rhodes et al. (2002) nor Choi et al. (2003) showed enrichment for any of the 3649 gene sets at FDR 5%; and, as shown in Supplementary Figure S5, the discrepancy between the meta-GSCA and enrichment tests is not due to the FDR threshold.

4.2 Diabetes

We performed a second meta-analysis with diabetes data obtained by searching the public repository NCBI GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) and DGAP (Diabetes Genome Anatomy Project). As of February 29, 2008, NCBI GEO returned 79 GEO Series (GSE) for the search term ‘diabetes’. After removing series only peripherally related with diabetes, series without Entrez Gene ID annotation, series with fewer than three biological replicates and series without raw data files uploaded, 16 datasets from human, mouse and rat remained eligible for analysis. DGAP provided an additional six datasets for which the diabetic and normal conditions were clearly described. A brief summary of the 22 datasets is given in Supplementary Table S2. After gene matching by NCBI HomoloGene build 61, the 22 datasets represent 2349 common genes and 2253 common gene sets defined by GO and KEGG of size at least 3. We further reduced the collection to include eight experiments with sample size larger than 5, based on the shape of the distribution of correlation coefficients obtained from simulations (Supplementary Fig. S6). The final eight sets are marked in Supplementary Table S2.

Meta-GSCA on the eight datasets identified 47 gene sets significantly preserved across studies at 5% FDR (sets are shown in Supplementary Table S3). The approach again identifies what are likely biologically meaningful gene sets. For example, the KEGG pathway for mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling was identified. This pathway is known to play a key role in both types I and II diabetes (Evans et al., 2003; Wellen and Hotamisligil, 2005). NR4A1, nuclear receptor subfamily 4, group A, member 1 in particular, included in this and many other significant sets, has been reported to be a regulator of hepatic glucose metabolism (Pei et al., 2006). PDK4, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase, isozyme 4a, well known to be associated with diabetes (Cadoudal et al., 2008; Kim et al., 2006), is another gene that also appears in many significant gene sets.

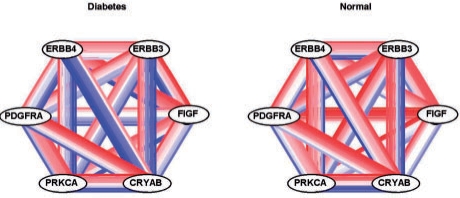

A particularly interesting gene set among the 47 is GO:0007169. Figure 5 shows a subset of six important genes selected from GO:0007169 as done for the lung cancer results shown in the lower panel of Figure 2. The gene set contains ERBB4, a gene known to be involved in pancreatic islet cell development (Huotari et al., 2002; Kritzik et al., 2000; Miettinen et al., 2000), which our group has recently shown to be predictive of type 2 diabetes (Keller et al., 2008). In the normal condition, ERBB4 is non-negatively correlated with CRYAB and PRKCA in seven of the eight studies; the correlations are largely negative in the diabetic condition.

Fig. 5.

GO:0007169 transmembrane receptor protein tyrosine kinase signaling. The six genes most DC between diabetic and normal are shown. Each pair of nodes is connected by eight edges, one for each of the eight studies. Edges represent co-expressions ranging from −1 (blue) to 1 (red).

5 DISCUSSION

Statistical methods for identifying DE genes were among the first developed for microarray data, with methods for detecting enrichment following soon thereafter. Many methods to detect enrichment (e.g. hypergeometric test) involve identifying DE genes and then gene sets for which there are more DE genes than expected by chance; others (e.g. GSEA; SAFE) consider all genes and calibrate set-level statistics via label permutations. The single study GSCA approach proposed here is most similar to GSEA (or SAFE) in that a single statistic is calculated for each gene set and calibrated via permutations across samples. A major difference is that unlike GSEA (or SAFE), the GSCA statistic evaluates pairwise co-expression, as opposed to gene-specific expression, across a gene set. The gene sets identified as a result are those showing distinct correlation profiles across conditions, which may or may not be related to differences in average expression. As a result, the GSCA provides complementary information to traditional GSEA approaches and should be done in addition to, not in lieu of, a GSEA.

Implementation of GSCA requires that a number of decisions be made. The most important ones concern choosing measures of correlation and dispersion. The results reported here were obtained using Pearson's correlation coefficients, although we note that a number of other measures could prove useful. For the lung cancer data considered, GSCA using Spearman's correlation coefficients resulted in an increased number of gene sets identified (specific results not shown). For example, 1055 gene sets were identified for the Harvard study data (268 agree with the 312 identified using Pearson's coefficients). A consideration of transformed correlation coefficients as well as alternative forms of the test statistic could also prove useful in the context of GSCA, particularly if the identification of specific correlation structures is of interest. Further simulation studies are required to provide general guidelines on the advantages and disadvantages of various implementations.

As with many dispersion indices one could consider, the ones proposed in Equations (1) and (2) can achieve significance for gene sets with a few highly DC gene pairs as well as those showing moderate evidence of DC across many pairs. As a result, it is interesting, informative and important to closely investigate the DC gene sets identified. The graphical summaries presented here can provide some insight into the gene pairs most DC across conditions.

In summary, the GSCA approach provides an FDR controlled list of gene sets DC between two or more biological conditions. Unlike previous work (Brown et al., 2002; Choi et al., 2005; Ihmels et al., 2005; Kostka and Spang, 2004; Oldham et al., 2006; Watson, 2006), the GSCA approach does not require that groups of genes be highly correlated in at least one biological condition. This feature is an important one, as gene pairs in known regulatory pathways often show relatively low correlations overall (see Supplementary Fig. S7). A second important feature of GSCA is that multiple studies are naturally accommodated. In particular, the consideration of co-expression facilitates combining data across potentially different platforms since the measurements for analysis (i.e. co-expressions) are necessarily on the same scale. Finally, the computational simplicity of the GSCA lends itself to larger problems. We have here considered two group analyses, but are currently working on applications to gene set mapping, where groups are defined by genotypes at a genetic marker.

6 CONCLUSIONS

The GSCA approach provides an FDR controlled list of gene sets DC between two or more biological conditions. It does not require that groups of genes be highly correlated in at least one biological condition and can be applied within a single study or across multiple studies. It should prove useful as a complement to traditional enrichment methods.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Michael Newton for comments that greatly improved the manuscript.

Funding: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive Kidney Diseases (grant 58037); National Institute of General Medical Sciences (grant 76274).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

REFERENCES

- Allison DB, et al. Microarray data analysis: from disarray to consolidation and consensus. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:55–65. doi: 10.1038/nrg1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariyanayagam-Baksh SM, et al. Malignant blue nevus: a case report and molecular analysis. Am. J. Dermatopathol. 2003;25:21–27. doi: 10.1097/00000372-200302000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry WT, et al. Significance analysis of functional categories in gene expression studies: a structured permutation approach. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1943–1949. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry WT, et al. A statistical framework for testing functional categories in microarray data. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2008;2:286–315. [Google Scholar]

- Beer DG, et al. Gene-expression profiles predict survival of patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Nat. Med. 2002;8:816–824. doi: 10.1038/nm733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A, et al. Classification of human lung carcinomas by mRNA expression profiling reveals distinct adenocarcinoma subclasses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13790–13795. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191502998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown VM, et al. High-throughput imaging of brain gene expression. Genome Res. 2002;12:244–254. doi: 10.1101/gr.204102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buijs JT, et al. BMP7, a putative regulator of epithelial homeostasis in the human prostate, is a potent inhibitor of prostate cancer bone metastasis in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 2007;171:1047–1057. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadoudal T, et al. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4: regulation by thiazolidinediones and implication in glyceroneogenesis in adipose tissue. Diabetes. 2008;57:2272–2279. doi: 10.2337/db08-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, et al. Combining multiple microarray studies and modeling interstudy variation. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl. 1):i84–i90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi JK, et al. Differential coexpression analysis using microarray data and its application to human cancer. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:4348–4355. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corn PG, El-Deiry WS. Microarray analysis of p53-dependent gene expression in response to hypoxia and DNA damage. Cancer Biol. Therapy. 2007;6:1858–1866. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.12.5330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas PB, et al. Gene expression levels assessed by oligonucleotide microarray analysis and quantitative real-time RT-PCR - how well do they correlate? BMC Genomics. 2005;6:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang CV, et al. The interplay between MYC and HIF in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:51–56. doi: 10.1038/nrc2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley S, et al. Coexpression pattern of c-myc associated genes in a small cell lung cancer cell line with high steady state c-myc transcription. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995;213:789–795. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagle LR, et al. Mutation of the MXI1 gene in prostate cancer. Nat. Genet. 1995;9:249–255. doi: 10.1038/ng0395-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JL, et al. Are oxidative stress-activated signaling pathways mediators of insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction? Diabetes. 2003;52:1–8. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon S, Gentleman R. Using GOstats to test gene lists for GO term association. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:257–258. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber ME, et al. Diversity of gene expression in adenocarcinoma of the lung. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:13784–13789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241500798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman R, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentleman R, et al. On the synthesis of microarray experiments. Bioconductor Project Working Papers, Working Paper 8. 2005 http://www.bepress.com/bioconductor/paper8. [Google Scholar]

- Harashima N, et al. Recognition of the Lck tyrosine kinase as a tumor antigen by cytotoxic T lymphocytes of cancer patients with distant metastases. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:323–332. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200102)31:2<323::aid-immu323>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho Y-Y, et al. Statistical methods for identifying differentially expressed gene combinations. In: Ochs MF, editor. Gene Function Analysis, Methods in Molecular Biology Series. Vol. 408. Clifton, NJ: Humana Press; 2007. pp. 171–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huotari M-A, et al. ErbB signaling regulates lineage determination of developing pancreatic islet cells in embryonic organ culture. Endocrinology. 2002;143:4437–4446. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihmels J, et al. Comparative gene expression analysis by a differential clustering approach: Application to the Candida albicans transcription program. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e39. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai N, et al. Identification of Lck-derived peptides capable of inducing HLA-A2-restricted and tumor-specific CTLs in cancer patients with distant metastases. Int. J. Cancer. 2001;94:237–242. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanovska ND, et al. Properdin deficiency in murine models of nonseptic shock. J. Immunol. 2008;180:6962–6969. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.10.6962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller MP, et al. A gene expression network model of type 2 diabetes links cell cycle regulation in islets with diabetes susceptibility. Genome Res. 2008;18:706–716. doi: 10.1101/gr.074914.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SK, et al. Identification of two distinct tumor-suppressor loci on the long arm of chromosome 10 in small cell lung cancer. Oncogene. 1998;17:1749–1753. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YI, et al. Insulin regulation of skeletal muscle PDK4 mRNA expression is impaired in acute insulin-resistant states. Diabetes. 2006;55:2311–2317. doi: 10.2337/db05-1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kostka D, Spang R. Finding disease specific alterations in the co-expression of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:194–199. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristiansen OP, et al. No linkage of P187S polymorphism in NAD(P)H: Quinone oxidoreductase (NQO1/DIA4) and type 1 diabetes in the Danish population. Hum. Mutat. 1999;14:67–70. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)14:1<67::AID-HUMU8>3.0.CO;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritzik MR, et al. Expression of ErbB receptors during pancreatic islet development and regrowth. J. Endoc. 2000;165:67–77. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1650067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal GW, et al. Lck associates with is activated by Kit in a small cell lung cancer cell line: inhibition of SCF-mediated growth by the Src family kinase inhibitor PP1. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4660–4666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, et al. A statistical method for identifying differential gene-gene co-expression patterns. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3146–3155. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H, et al. Integrative analysis reveals the direct and indirect interactions between DNA copy number aberrations and gene expression changes. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:889–896. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mah N, et al. A comparison of oligonucleotide and cDNA-based microarray systems. Physiol. Genomics. 2004;16:361–370. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00080.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen PJ, et al. Impaired migration and delayed differentiation of pancreatic islet cells in mice lacking EGF-receptors. Development. 2000;127:2617–2627. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.12.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito M, et al. Identification of Lck-derived peptides applicable to anti-cancer vaccine for patients with human leukocyte antigen-A3 supertype alleles. Br. J. Cancer. 2007;97:1648–1654. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton MA, et al. On differential variability of expression ratios: improving statistical inference about gene expression changes from microarray data. J. Comput. Biol. 2001;8:37–52. doi: 10.1089/106652701300099074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton MA, et al. Random-set methods identify distinct aspects of the enrichment signal in gene-set analysis. Ann. Appl. Stat. 2007;1:85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham MC, et al. Conservation and evolution of gene coexpression networks in human and chimpanzee brains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:17973–17978. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605938103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park KH, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the TGFB1 gene and lung cancer risk in a Korean population. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2006;169:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parmigiani G, et al. A cross-study comparison of gene expression studies for the molecular classification of lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:2922–2927. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei L, et al. NR4A orphan nuclear receptors are transcriptional regulators of hepatic glucose metabolism. Nat. Med. 2006;12:1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/nm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen S, et al. Allelic loss on chromosome 10q in human lung cancer: association with tumour progression and metastatic phenotype. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;77:270–276. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan N, et al. The high-level similarity of some disparate gene expression measures. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3032–3038. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes DR, et al. Meta-analysis of microarrays: interstudy validation of gene expression profiles reveals pathway dysregulation in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4427–4433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rottino A, et al. A study of the serum properdin levels of patients with malignant tumors. Cancer. 2006;11:351–356. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195803/04)11:2<351::aid-cncr2820110219>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfer J, Strimmer K. An empirical Bayes approach to inferring large-scale gene association networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:754–764. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartor MA, et al. LRpath: a logistic regression approach for identifying enriched biological groups in gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:211–217. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shedden K, Taylor J. Differential correlation detects complex associations between gene expression and clinical outcomes in lung adenocarcinomas. In: Shoemaker JS, Lin SM, editors. Methods of Microarray Data Analysis IV. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 121–131. [Google Scholar]

- Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CM, et al. Properdin plays a protective role in polymicrobial septic peritonitis. J. Immunol. 2008;180:3313–3318. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. Gene Ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao CC, et al. Inhibition of MXI1 suppresses HIF-2α-dependent renal cancer tumorigenesis. Cancer Biol. Therapy. 2008;7:1620–1628. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.10.6583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voy BH, et al. Extracting gene networks for low-dose radiation using graph theoretical algorithms. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006;2:e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, et al. Merging microarray data, robust feature selection, and predicting prognosis in prostate cancer. Cancer Inform. 2007;2:87–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson M. CoXpress: differential co-expression in gene expression data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:509. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:1111–1119. doi: 10.1172/JCI25102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan W, Chen X. Targeted repression of bone morphogenetic protein 7, a novel target of the p53 family, triggers proliferative defect in p53-deficient breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9117–9124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, et al. Extracting three-way gene interactions from microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2903–2909. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.