Abstract

Motivation: With the availability of many ‘omics’ data, such as transcriptomics, proteomics or metabolomics, the integrative or joint analysis of multiple datasets from different technology platforms is becoming crucial to unravel the relationships between different biological functional levels. However, the development of such an analysis is a major computational and technical challenge as most approaches suffer from high data dimensionality. New methodologies need to be developed and validated.

Results: integrOmics efficiently performs integrative analyses of two types of ‘omics’ variables that are measured on the same samples. It includes a regularized version of canonical correlation analysis to enlighten correlations between two datasets, and a sparse version of partial least squares (PLS) regression that includes simultaneous variable selection in both datasets. The usefulness of both approaches has been demonstrated previously and successfully applied in various integrative studies.

Availability: integrOmics is freely available from http://CRAN.R-project.org/ or from the web site companion (http://math.univ-toulouse.fr/biostat) that provides full documentation and tutorials.

Contact: k.lecao@uq.edu.au

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 BACKGROUND

In the context of an integrative systems biology approach, the simultaneous analysis of two datasets is an important task to better understand the relationships between different biological functional levels. For example, it is becoming increasingly clear that the integration of ‘omics’ data, such as transcriptomics, proteomics or metabolomics will provide a better understanding of biological systems. However, the few existing integrative approaches are facing computational issues because of the ‘large p, small n’ problem as is the case of canonical correlation analysis (CCA; Hotelling, 1936) that requires to compute the inverse of singular matrices. Another challenge is to give interpretable results, i.e. to answer the following questions (i) which variables from both types are related to each other and (ii) which relevant variables provide more insight into the biological experimental hypotheses? The solution is to perform variable selection while combining the two types of variables in the modeled integration process, an issue that is challenging in statistics. The integration and the selection of two different types of variables is nowadays an active research subject as data of high dimension are arising in numerous studies. They require appropriate methodologies to extract or summarize the relevant information.

To address this problem, we developed and implemented two useful approaches: a regularized version of CCA to overcome computational issues in CCA when p> >n (González et al., 2009), and a variant of partial least squares (PLS) regression (Wold, 1966) called sparse PLS (Lê Cao et al., 2008, 2009) to simultaneously integrate and select variables using lasso penalization (Tibshirani, 1996). Both approaches were thoroughly assessed on several biological studies and were proven to produce relevant results. integrOmics provides not only various frameworks to efficiently analyze highly dimensional data but also numerous graphical outputs to guide the interpretation of the results, as illustrated in the next sections.

2 METHODS AND IMPLEMENTATION

We denote the two-block data matrices X (n × p) and Y (n × q) with standardized columns, where the variables p and q are of two different types (e.g. gene and metabolite expressions) and are measured on the same samples or individuals n.

CCA and PLS are both exploratory approaches which enable the integration of two datasets, but they fundamentally differ in essence. CCA maximizes the correlation between linear combinations of the variables from each dataset, whereas PLS maximizes the covariance. To be solved, CCA requires the computation of the inverses of the covariance matrices XX′ and YY′ that are singular if p> >n. Vinod (1976) and González et al. (2008), therefore, introduced l2 penalties on the covariance matrices so as to make them invertible in a ridge CCA (rCCA). On the contrary, PLS circumvents this ill-conditioned matrices issue by performing local regressions. Both approaches seek for (i) p- and q-dimensional weight vectors, called canonical factors or loading vectors, and (ii) n-dimensional vectors, called score or latent vectors. In order to give interpretable results and remove noisy variables, Lê Cao et al. (2008, 2009) proposed to add l1 penalizations to each PLS loading vector, in which the magnitude of the coefficients indicate the importance of the variables in the integrative model. As a result, many coefficients in these vectors are set to zero, which naturally allows for a simultaneous variable selection in the two datasets. Two types of analysis were proposed in sPLS: a regression analysis for a causal relationship between the two datasets, or a canonical analysis for a reciprocal relationship similar to a CCA framework.

The functions in the CCA R package (González et al., 2008) were rewritten in integrOmics to standardize the outputs in our package.

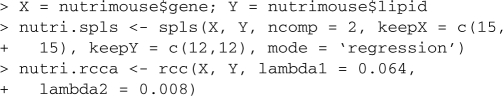

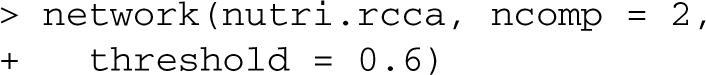

The R script below shows the calls in integrOmics for the nutrimouse data included in the package. The user needs to specify (i) the number of variables to select in the X and Y datasets with sPLS, or (ii) the regularization parameters for each dataset with rCCA.

3 SOFTWARE FEATURES

Numerical outputs: numerous criteria are proposed to assess the quality of the analysis in integrOmics. The Q2 criterion (Tenenhaus, 1998) can be computed to determine the number of components to choose from the (s)PLS regression model. The root mean squared error prediction can be used to choose the optimal number of variables to be selected using cross-validation. The user can also estimate the predicted value of a new sample in the model and regularization parameters in rCCA can be tuned using cross-validation. Missing values of each dataset can be efficiently imputed with a singular value decomposition using NIPALS, an iterative version of principal component analysis (Wold, 1966).

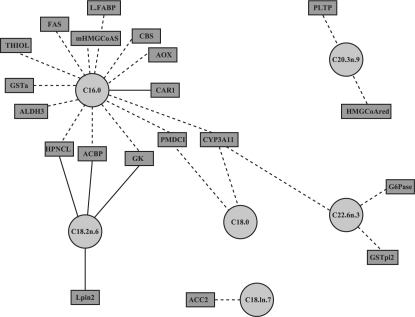

Visualization outputs: focus is also made on visualization to guide the interpretation of the results. Scatter plots of the score (latent) vectors from the first dimensions allow the user to identify similarities between the samples. Often, these similarities (clusters of samples) were found to have biological meaning (González et al., 2009; Lê Cao et al., 2009, see Supplementary Material). Further, the (selected) variables can be represented by projecting them on correlation circles to highlight their correlation structure (González et al., 2008, see Supplementary Material). integrOmics also enables the inference of large-scale association networks between the two datasets with the use of network graphical displays (Fig. 1), where the edges represent relevant associations between the variables (nodes):

Fig. 1.

Example of variable visualization outputs with integrOmics.

Interactive graph drawing may be used to include more relationships in the network. Further examples and outputs can be found on integrOmics web site.

Versatility of integrOmics: rCCA and sPLS have been successfully applied in various biological contexts where p+q> >n. sPLS with regression mode has been applied to integrate gene expression with metabolite expression, clinical chemistry or fatty acids measurements, where often p>5000−22000 and q=10−150 (Lê Cao et al., 2008). rCCA or sPLS with canonical mode were applied to relate physicochemical measurements with sensory variables or to relate gene expression measured on different platforms (p ≃ q >1500), see Combes et al. (2008), González et al. (2009), Yergeau et al. (2008) and Lê Cao et al. (2009) for more details. We are currently investigating the versatility of sPLS to integrate discrete and continuous variables (e.g. clinical variables and microarray data in cancer studies) or, in a regression context, to relate single nucleotide polymorphism to one or several quantitative or qualitative traits.

Funding: Australian Research Council under the ARC Centres of Excellence program; ARC Centre of Excellence in Bioinformatics (to K-A.L.C.); Program on Food and Human Nutrition of the French National Research Agency, ANR PNRA 2006, project 2.23, plast-impact (to I.G.).

Conflict of Interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Combes S, et al. Relationships between sensorial and physicochemical measurements in meat of rabbit from three different breeding systems using canonical correlation analysis. Meat Sci. 2008;80:835–841. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González I, et al. CCA: an R package to extend canonical correlation analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008;23:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- González I, et al. Highlighting relationships between heteregeneous biological data through graphical displays based on regularized canonical correlation analysis. J. Biol. Syst. 2009;17:173–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hotelling H. Relations between two sets of variates. Biometrika. 1936;28:321–377. [Google Scholar]

- Lê Cao K-A, et al. A sparse PLS for variable selection when integrating Omics data. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2008;7 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1390. Article 35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê Cao K-A, et al. Sparse canonical methods for biological data integration: application to a cross-platform study. BMC Bioinformatics. 2009;10 doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-34. Article 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenhaus M. La régression PLS: théorie et pratique. Paris: Editions Technip; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B. 1996;58:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Vinod HD. Canonical ridge and econometrics of joint production. J. Econom. 1976;4:147–166. [Google Scholar]

- Wold H. Estimation of principal components and related models by iterative least squares. In: Krishnaiah P, editor. Multivariate Analysis. New York: Academic Press, Wiley; 1966. pp. 391–420. [Google Scholar]

- Yergeau E, et al. Environmental microarray analyses of Antarctic soil microbial communities. Int. Soc. Microbial. Ecol. J. 2008;3:340–351. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.