Abstract

The two kinds of sex chromosomes in the heterogametic parent are transmitted to offspring with different sexes, causing opposite-sex siblings to be completely unrelated for genes located on these chromosomes. Just as the nest-parasitic cuckoo chick is selected to harm its unrelated nest-mates in order to garner more shared resources, sibling competition causes the sex chromosomes to be selected to harm siblings that do not carry them. Here we quantify and contrast this selection on the X and Y, or Z and W, sex chromosomes. We also develop a hypothesis for how this selection can contribute to the decay of the non-recombining sex chromosome.

Keywords: sexual conflict, sibling competition, sex chromosomes, sexually antagonistic zygotic drive, degenerate Y chromosome, Hamilton's rule

1. Introduction

The asymmetrical transmission of a parent's X and Y, or Z and W, sex chromosomes to opposite-sex siblings, when coupled with sibling competition, selects for a meiotic-drive-like process called sexually antagonistic zygotic drive (hereafter SA-zygotic drive; Miller et al. 2006; Rice et al. 2008). Meiotic drive operates via the differential success of haploid gametes from the same parent (reviewed in Hurst et al. 1996; Burt & Trivers 2006). SA-zygotic drive operates in an analogous way, but in the next generation, via differential success of diploid siblings. Just as meiotic drive elements are selected to harm the gametes that do not carry them, so too are the sex chromosomes selected to harm the competing siblings of the sex in which they are not represented. SA-zygotic drive can be mediated through (i) the heterogametic parent via sex-specific parental investment and/or epigenetic parental effects that harm only one sex of siblings and (ii) the competing siblings themselves, via sex-specific antagonistic interactions (Rice et al. 2008). Here we focus on interactions between siblings. Throughout, the term ‘sex chromosomes’ refers to their regions that do not recombine in the heterogametic sex. For simplicity, but without loss of generality, we will assume that males are the heterogametic sex.

Many cuckoo species of birds are brood parasites that lay their eggs in the nests of other bird species (hosts) and these surrogate parents rear their young. Cuckoo's chicks have evolved to be highly harmful to their unrelated nest-mates, e.g. ejecting them from the nest, pecking them and out-competing them for resources via faster development and super-stimulating begging displays (Soler & Soler 2000). Paternal X and Y sex chromosomes, in opposite-sex siblings, have the same absence of relatedness as that between cuckoo and host chicks. Correspondingly, paternally inherited sex chromosomes are selected, as cuckoos, to harm brood-mates they are not transmitted through. Here we quantify the selective constraints on SA mutations occurring on sex chromosomes that code for phenotypes that harm sisters (Y-linked) or brothers (X-linked). We use our results to motivate a new hypothesis by which SA-zygotic drive can contribute to the evolution of degenerate Y and W sex chromosomes.

2. Material and methods

(a). Model: application of Hamilton's rule

To quantify the constraints on the accumulation of Y-linked mutations that harm sisters, and X-linked mutations that harm brothers, we begin with Hamilton's rule (Hamilton 1964) for the evolution of altruism: C/B<r, where C is the fitness cost of an altruistic behaviour; B is the fitness benefit to the individual receiving the altruism; and r is the level of relatedness (proportion shared genes) between the two individuals. To convert Hamilton's rule to the case of a focal individual harming one sex of sibling, we multiply C and B (numerator and denominator) by −1, so the ‘altruism’ is converted to harm and the ‘cost’ to the focal individual becomes a benefit. Let B H be fitness benefit to the focal individual of harming another individual and C H be the fitness cost to the individual receiving the harm. Hamilton's rule when applied to harmful interactions between individuals becomes: B H/C H<r, or when expressed as a cost–benefit ratio C H/B H<1/r.

(b). Model: population genetic approach

We consider a randomly mating population in which each family has two siblings. With an even sex ratio, the probabilities that these are sisters, brothers or one of each sex are 1/4, 1/4 and 1/2, respectively. We focus on a single diallelic locus with a mutant allele (which is rare initially) decreasing the fitness (viability) of the brother from 1 to 1−C H, while simultaneously increasing the fitness of its carrier (whether male or female) from 1 to 1+B H. We assume that in families with two brothers, both carrying mutant alleles, their effects on each other combine multiplicatively resulting in fitness (1+B H)(1−C H).

(i) Autosomal locus

Allele a produces no antagonistic effects and allele A produces a brother-harming phenotype in both sexes. Let h be the frequency of genotype Aa, which we assume is small. The frequency of Aa by aa matings is then 2h and one can show that in the next generation (see the electronic supplementary material),

|

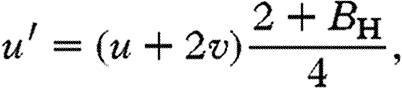

(ii) X-linked locus

We assume male heterogamety, that allele x has no antagonistic effects and a rare allele X produces a brother-harming phenotype. In this case, there are only two female genotypes, Xx and xx, at non-trivial frequencies at the adult stage, which we define to be u and 1−u, respectively. There are also two male genotypes at the adult stage, X and x, at frequencies v and 1−v, respectively. Only three types of mating occur at non-trivial frequency: Xx×x at frequency u; xx×X at frequency v; and xx×x at frequency 1−u−v. Under these conditions, one can show that in the next generation (see the electronic supplementary material),

|

|

3. Results

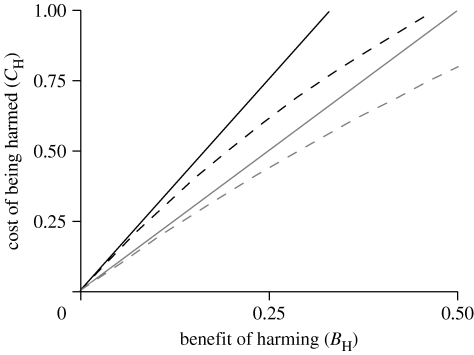

Consider a new mutation in a large outbred population. When Y-linked, r=0 between brothers and sisters, so sister-harming mutations will be favoured by selection so long as they help brothers. For the X chromosome, the same logic applies to an imprinted brother-harming mutation that is expressed exclusively when inherited from the father (although it would be selected only one-third of the time). But in the more general case when the X-linked mutation is not imprinted, Hamilton's rule must be met when averaged across the sexes, i.e. the constraints are C H/B H<1/0 when the X is paternally inherited and C H/B H<2 when inherited from the mother. Since two-thirds of X chromosomes reside in females, the weighted average result is (1/3)×B H+(2/3)×B H>0+(1/3)×C H, which implies that C H/B H<3. These X and Y constraints are unchanged with multiple paternity. For an autosomal gene, the constraint is C H/B H<2 (see Mock & Parker (1997) for a more general treatment of the autosomes). In summary, selection favours any sister-harming mutation that is Y-linked so long as some benefit accrues to brothers (cost/benefit<∞). Brother-harming X-linked mutations, lacking a special form of imprinting, are more strongly constrained than the Y, but less constrained than the autosomes (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The constraints on the accumulation of new mutations that are Y-linked and harm sisters, X-linked and harm brothers or autosomal and harm one sex of sibling. Y-linked mutations accumulate over the entire parameter space, X and autosomal mutations only when they map below the curves. Black curves denote X-linkage, grey curves autosomal linkage; solid curves are based on Hamilton's rule and dashed curves are based on a population genetic model.

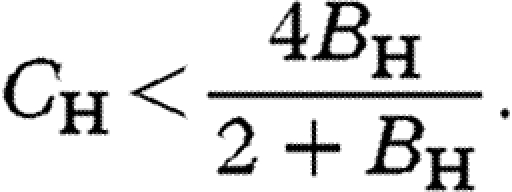

Using our population genetic model for an autosomal locus, one can show that the brother-harming allele A invades when rare if (see the electronic supplementary material)

|

3.1 |

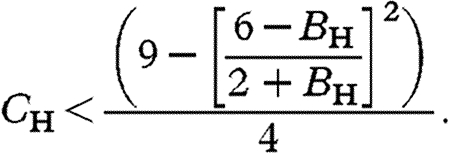

With X-linkage, a brother-harming X allele invades when rare if (see the electronic supplementary material)

|

3.2 |

These results converge on those based on Hamilton's rule when B H is small: on the autosomes C H/B H<2 and on the X C H/B H<3 (left side of figure 1). With stronger selection, however, there is stronger constraint on both the X and autosomes (right side of figure 1).

Searching the literature, we found specific examples of neither Y-linked mutations that cause brothers to harm their sisters nor X-linked mutations causing both sexes to harm brothers. There are, however, reports in which siblings of the opposite sex are more aggressive to one another than same-sex siblings (e.g. Dunn & Kendrick 1981; Bortolotti 1986; Drummond et al. 1991; Legge 2000; Moura 2003). However, we also found several examples where aggression was more pronounced between siblings of the same sex (e.g. Minnett et al. 1983; Frank et al. 1991; Snowdon & Pickhard 1999).

4. Discussion

Because X chromosomes in sisters are more closely related than those in brothers, and than the autosomes in both sexes, the homogametic sex is expected to be more cooperative (Kawecki 1991)—a prediction with at least some empirical support (see Haig (2000) for a review of this literature). Here we have shown that X chromosomes are also expected to more readily accumulate selfish mutations that harm brothers (figure 1). Although we were unable to find any studies that documented X-coded, brother-harming phenotypes, we found no studies that specifically screened for this phenotype.

In contrast to the X, Y chromosomes have no restrictions on accumulating sister-harming mutations (full parameter space in figure 1). From the perspective of X and autosomes, Y chromosomes are selected to accumulate ultra-selfish mutations that harm sisters that do not carry them, irrespective of the cost–benefit ratio (C H/B H; figure 1). Despite this unconstrained selection, we were unable to document established cases of sister-harming Y chromosomes in the literature, but, as for the X, we found no genetic screens that directly assayed for this Y-coded phenotype. We next propose a model, as a hypothesis, in which antagonistic coevolution keeps Y-coded, sister-harming phenotypes rare, and thereby leads to the decay of the Y.

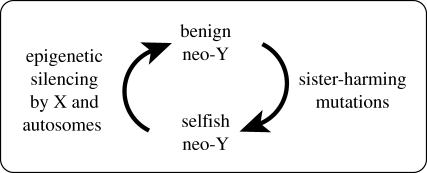

Hamilton (1967) proposed that Y chromosomes degenerated because the X and autosomes were selected to shut down Y-linked meiotic drive. Charlesworth (1978) dismissed this scenario as a general explanation for the degeneration of Y chromosomes because of the apparent paucity of genes that can evolve to cause meiotic drive in males, and because of the cost of shutting down a large region of the nascent Y chromosome (due to hemizygous gene expression without dosage compensation). However, Hamilton's logic, when applied to SA-zygotic drive, may be a more potent factor leading to the degeneration of Y chromosomes. In mice, more than 80 per cent of the genome (structural genes) is expressed in the brain (Sunkin & Hohmann 2007). As a consequence, many genes can potentially contribute to behaviour, at least some of which could influence sister-harming behavioural phenotypes. Suppose that a sister-harming mutation accumulated on a nascent Y chromosome, leading to SA-zygotic drive. When it harmed sisters more than when it helped brothers, the entire genome would be selected to silence the mutation (figure 2). One mechanism by which genomes are known to shut down harmful genes, such as transposable elements, is via epigenetic silencing (Slotkin & Martienssen 2007). Recent evidence indicates that transacting, ncRNA-based silencing of only one allele at a diploid locus is feasible (Rinn et al. 2007). Recurrent silencing of sister-harming, Y-linked genes could, in principle, contribute to the degeneration of the Y sex chromosome (figure 2). The effect of such silencing would be magnified when high sequence similarity between alleles on the nascent X and Y required the ncRNA to target sequences flanking a sister-harming, Y-linked allele (that had diverged sufficiently to be uniquely targeted), leading to collateral silencing of any intervening genes. In this case many, and perhaps most, silenced genes on the Y would not code for sister-harming phenotypes.

Figure 2.

Coevolution between selfish Y chromosomes that code for harmful sibling–sibling interactions that harm sisters, and the X and autosomes that are selected to silence them.

Our study illustrates why the evolution of nascent sex chromosomes is ‘dangerous’ to the autosomes in all species with sibling competition: paternally inherited sex chromosomes are selected to harm the sex of siblings that do not carry them. This selection is more constrained on the X than the Y. Its ramifications may include elevated hostility among siblings, especially those of opposite sex, and antagonistic, intragenomic coevolution that, similar to Hill Robertson effects (Bachtrog & Charlesworth 2000; Nicolas et al. 2005), contributes to the decay of the Y.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project came from the National Science Foundation (W.R.R. and S.G.), the National Institutes of Health (W.R.R. and S.G.) and the Wenner-Gren Foundations (U.F.).

Footnotes

One contribution of 16 to a Special Feature on ‘Sexual conflict and sex allocation: evolutionary principles and mechanisms’.

References

- Bachtrog D., Charlesworth B.2000Reduced levels of microsatellite variability on the neo-Y chromosome of Drosophila miranda. Curr. Biol 10, 1025–1031doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00656-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortolotti G.R.1986Influence of sibling competition on nestling sex-ratios of sexually dimorphic birds. Am. Nat 127, 495–507doi:10.1086/284498 [Google Scholar]

- Burt A., Trivers R.Genes in conflict: the biology of selfish genetic elements 2006Cambridge, MA:Belknap Press of Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B.1978Model for evolution of Y chromosomes and dosage compensation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 75, 5618–5622doi:10.1073/pnas.75.11.5618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond H., Osorno J.L., Torres R., Chavelas C.G., Larios H.M.1991Sexual size dimorphism and sibling competition: implications for avian sex-ratios. Am. Nat 138, 623–641doi:10.1086/285238 [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J., Kendrick C.1981Social behavior of young siblings in the family context: differences between same-sex and different-sex dyads. Child Dev 52, 1265–1273doi:10.2307/1129515 [Google Scholar]

- Frank L.G., Glickman S.E., Licht P.1991Fatal sibling aggression, precocial development, and androgens in neonatal spotted hyenas. Science 252, 702–704doi:10.1126/science.2024122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haig D.2000Genomic imprinting, sex-biased dispersal, and social behavior. Ann. NY Acad. Sci 907, 149–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W.D.1964The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J. Theor. Biol 7, 1–16doi:10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W.D.1967Extraordinary sex ratios. Science 156, 477–488doi:10.1126/science.156.3774.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurst L.D., Atlan A., Bengtsson B.O.1996Genetic conflicts. Q. Rev. Biol 71, 317–364doi:10.1086/419442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawecki T.J.1991Sex-linked altruism: a stepping-stone in the evolution of social behavior. J. Evol. Biol 4, 487–500doi:10.1046/j.1420-9101.1991.4030487.x [Google Scholar]

- Legge S.2000Siblicide in the cooperatively breeding laughing kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol 48, 293–302doi:10.1007/s002650000229 [Google Scholar]

- Miller P.M., Gavrilets S., Rice W.R.2006Sexual conflict via maternal-effect genes in ZW species. Science 312, 73.doi:10.1126/science.1123727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnett A.M., Vandell D.L., Santrock J.W.1983The effects of sibling status on sibling interaction: influence of birth order, age spacing, sex of child, and sex of sibling. Child Dev 54, 1064–1072doi:10.2307/1129910 [Google Scholar]

- Mock D.W., Parker G.A.1997The evolution of sibling rivalry. Oxford Series in Ecology and Evolution Oxford, UK; New York, NY:Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- Moura A.C.D.2003Sibling age and intragroup aggression in captive Saguinus midas midas. Int. J. Primatol 24, 639–652doi:10.1023/A:1023748616043 [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas M., et al. 2005A gradual process of recombination restriction in the evolutionary history of the sex chromosomes in dioecious plants. PLoS Biol 3, 47–56doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice W.R., Gavrilets S., Friberg U.2008Sexually antagonistic ‘zygotic drive’ of the sex chromosomes. PLoS Genet 4, e1000313.doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinn J.L., Wang J.K., Allen N., Mikels A.J., Nusse R., Helms J.A., Chang H.Y.2007Site-specific induction of epidermal fates by dermal HOX transcriptional program. J. Invest. Dermatol 127, S109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotkin R.K., Martienssen R.2007Transposable elements and the epigenetic regulation of the genome. Nat. Rev. Genet 8, 272–285doi:10.1038/nrg2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowdon C.T., Pickhard J.J.1999Family feuds: severe aggression among cooperatively breeding cotton-top tamarins. Int. J. Primatol 20, 651–663doi:10.1023/A:1020796517550 [Google Scholar]

- Soler J.J., Soler M.2000Brood–parasite interactions between great spotted cuckoos and magpies: a model system for studying coevolutionary relationships. Oecologia 125, 309–320doi:10.1007/s004420000487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunkin S.M., Hohmann J.G.2007Insights from spatially mapped gene expression in the mouse brain. Hum. Mol. Genet 16, R209–R219doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]