Abstract

S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) is an alcohol dehydrogenase involved in the regulation of S-nitrosothiols (SNOs) in vivo. Knock-out studies in mice have shown that GSNOR regulates the smooth muscle tone in airways and the function of β-adrenergic receptors in lungs and heart. GSNOR has emerged as a target for the development of therapeutic approaches for treating lung and cardiovascular diseases. We report three compounds that exclude GSNOR substrate, S-nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) from its binding site in GSNOR and cause an accumulation of SNOs inside the cells. The new inhibitors selectively inhibit GSNOR among the alcohol dehydrogenases. Using the inhibitors, we demonstrate that GSNOR limits nitric oxide-mediated suppression of NF-κB and activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Our findings reveal GSNOR inhibitors to be novel tools for regulating nitric oxide bioactivity and assessing the role of SNOs in vivo.

S-Nitrosylation of cellular proteins has emerged as the key reaction through which NO2 controls the function of a wide array of cellular proteins (1). Through S-nitrosylation, NO has been shown to regulate smooth muscle tone, apoptosis, and NF-κB activity (2–5). Whereas S-nitrosylation mediates many NO effects inside the body, denitrosylation pathways inside the cells terminate these effects. Among the enzymes capable of denitrosylating SNOs (6–9), the ubiquitously expressed GSNOR has been shown to be operative in vivo (10, 11).

GSNOR, a member of the alcohol dehydrogenase family (12), indirectly regulates SNOs inside the cells by reducing GSNO, a NO metabolite arising from the reaction of glutathione with reactive nitrogen species (11). Due to its role in the turnover of nitrosylation of intracellular proteins, GSNOR has become an important target for developing agents that modulate NO bioactivity inside cells. The therapeutic potential of preventing the breakdown of SNOs via inhibition of GSNOR has been demonstrated in mice lacking GSNOR. GSNOR-deficient mice showed significantly low airway hyperresponsivity to allergen challenge and increased β-adrenergic receptor expression and function in lungs and heart (4, 5). This suggested GSNOR inhibition to be beneficial for the treatment of lung and cardiovascular diseases.

We report here novel inhibitors of GSNOR that exclude GSNO from its binding site and preferentially inhibit GSNOR among the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) isozymes. Using the new inhibitors, we demonstrate that GSNOR actively regulates S-nitrosylation of proteins stemming from nitric-oxide synthase activity. Among the key cellular processes regulated by GSNOR are the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB and soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

All of the chemicals used in the experiments were purchased from Sigma. RAW 264.7 and A549 cells, DMEM, and fetal bovine serum were purchased from American Tissue and Cell Culture. Recombinant human GSNOR, ADH1B (β2-ADH), ADH4 (π-ADH), and ADH7 (σ-ADH) were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified in the Indiana University School of Medicine Protein Expression Core. Compounds C1–C3 were purchased from ChemDiv Inc.

High Throughput Screening

The screening for GSNOR inhibitors was performed using a library of 60,000 compounds from ChemDiv Inc. in the Chemical Genomics Core facility at Indiana University. Screening was conducted in 384-well plates and involved incubating GSNOR with 12.5 μm compound, 1 mm each NAD+ and octanol in 0.1 m sodium glycine, pH 10. Enzyme activity was determined by measuring the rate of production of NADH spectrophotometrically at 340 nm. Inhibition of GSNOR was calculated from the ratio of enzyme activity in the presence of compounds to that in no compound controls performed on the same plate. Following their identification from the high throughput screening, the GSNOR-inhibitory properties of the initial hits were confirmed at the pH 10 using octanol as the substrate and at pH 7.5 using GSNO as the substrate (see legend of Table 1 for details of the assay).

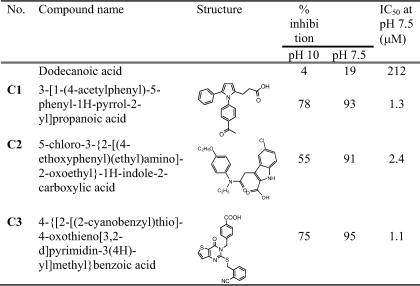

TABLE 1.

Structures of GSNOR inhibitors

Inhibition studies at pH 10 were performed in 0.1 m sodium glycine containing 1 mm octanol, 1 mm NAD+, 0.1 mm EDTA, and 50 μm inhibitor. Inhibition studies at pH 7.5 were performed in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 15 μm NADH, 10 μm GSNO, 0.1 mm EDTA, and 50 μm inhibitor.

Inhibition of ADH Isozymes by the C1–C3

Inhibition of the ADH1B (β2-ADH), ADH4 (π-ADH), and ADH7 (σ-ADH) was evaluated by determining the inhibitory effect of GSNOR inhibitors on the rate of oxidation of ethanol by each of these ADH isozymes. The assay mixture contained a saturating amount of NAD+ (1–2 mm) and ethanol at its Km concentration for each of the respective enzyme. All assays were performed at 25 °C in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 0.1 mm EDTA and involved determining the rate of formation of NADH spectrophotometrically at 340 nm. Specific assay conditions for each isozyme are as follows. (a) Studies with ADH1B involved adding 3.5 μg of the enzyme to the assay mixture containing 2 mm NAD+, 1 mm ethanol, and the inhibitor. (b) Studies with ADH7 involved adding 0.5 μg of enzyme to the assay mixture containing 2 mm NAD+, 30 mm ethanol, and the inhibitor. (c) Studies with ADH4 involved adding 19.5 μg of the enzyme to the assay mixture containing 1 mm NAD+, 35 mm ethanol and the inhibitor. (d) Studies with GSNOR involved adding 0.1 μg of the enzyme to an assay mixture containing 15 μm NADH, 5 μm GSNO, and the inhibitor.

Dead End Inhibition Studies

Inhibition experiments with the GSNOR inhibitors were conducted at 25 °C in 3 ml of 50 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.5) containing 0.1 mm EDTA. Five different concentrations of GSNO or NADH were used when they were the varied substrates and maintained at 10 and 15 μm, respectively, when present as the nonvaried substrate. A minimum of three inhibitor concentrations were used, and the rate of NADH and GSNO consumption was determined spectrophotometrically at 340 nm. The data were fit to the competitive, noncompetitive, and uncompetitive inhibition models, and the model best fitting the data was chosen on the basis of F-statistics performed using the Graphpad Prism 4.0.

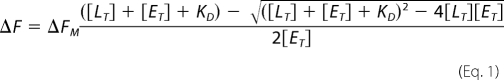

Fluorescence Studies

Fluorescence studies were conducted in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5, at room temperature using a Fluoromax-2 fluorescence spectrometer (Instruments S.A., Inc., Edison, NJ). The equilibrium dissociation constant of GSNOR inhibitors was determined by measuring the changes in the fluorescence of GSNOR-bound NADH (λex = 350 nm; λem = 455 nm) upon the addition of inhibitor. During the experiment, increasing amounts of inhibitor were added to a solution containing 2 μm GSNOR and 1.7 μm NADH. The decrease in fluorescence at 455 nm with each addition of inhibitor was plotted against the final concentration of inhibitor, and the data were fitted to Equation 1 using nonlinear regression to obtain the dissociation constant of the inhibitor for GSNOR-NADH complex,

|

In Equation 1, ΔF is the change in the fluorescence at 455 nm upon the addition of inhibitor. ΔFM is the maximum fluorescence change that was obtained from curve fitting. [ET] and [LT] are the concentrations of GSNOR and inhibitor, respectively. KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant for the formation of GSNOR·NADH·inhibitor complex. The data were fitted using the Graphpad Prism 4.0.

Determination of Nitroso Species Accumulation in RAW Cells Using the Triiodide-based Chemiluminescence Method

RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 200 units/ml penicillin, and 200 μg/ml streptomycin. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and 95% air. For the experiments, 1–2 × 106 cells were plated in 6-well plates with or without 33 μm compounds 16 h before the experiment. (Later experiments showed that pretreatment with compounds had no effect on the rate of accumulation of nitroso species inside the cells). On the day of the experiment, the medium was replaced with a fresh 3 ml of medium, and the cells were treated with compounds for a predetermined length of time. Following the incubation period, the cells were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline and scraped off of the plate in 250 μl of lysis buffer (50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, containing 50 mm N-ethylmaleimide and 1 mm EDTA) and lysed by sonication using a microtip probe (three pulses of 30% duty cycle; 2 output control on a Branson Sonicator). The cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation (10 min at 16,000 × g), and the cell lysate was analyzed for protein concentration using the Bio-Rad dye-binding protein assay. The concentration of nitroso compounds in the cell lysate was determined using the triiodide-based chemiluminescence method (13) using a Sievers 280 nitric oxide analyzer. Briefly, cell lysates were treated with 15% (v/v) of a sulfanilamide solution (5% (w/v) in 0.2 m HCl) and kept at room temperature for 5 min to remove nitrite. The triiodide mixture was prepared fresh every day as described earlier (14) and kept at 60 °C in the reaction vessel. The concentration of nitroso species was derived from a standard curve generated using GSNO.

S-Nitrosothiol Detection in RAW 264.7 Cells Using the Biotin Switch Assay

RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in 100-mm dishes using DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated serum and 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin. On the day of the experiment, the medium was replaced with a fresh medium containing C3 (33 μm) alone or a mixture of C3 and l-NAME (1.1 mm), and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for varied lengths of time. At indicated times, the cells were quenched, and the lysate was analyzed for S-nitrosothiol content by the biotin switch assay as described by Jaffrey et al. (15) with modifications suggested by Wang et al. (16) and Zhang et al. (17). Briefly, free sulfydryls in ∼200 μg of cell lysate were blocked with 20 mm S-methyl methanethiosulfonate in 1 ml of HEN buffer (250 mm HEPES, pH 7.7, containing 1 mm EDTA and 0.1 mm Neocupronine) containing 2% SDS at 50 °C for 20 min. Free S-methyl methanethiosulfonate was removed by gel filtration spin columns, and the blocked proteins were labeled with 1 mm (N-(6-(biotinamido)hexyl)-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)-propionamide) (Pierce) in the presence or absence of 30 mm ascorbate and 2 μm CuCl for 3 h. Equal amounts of proteins were loaded in each lane, and the degree of biotinylation (and hence S-nitrosylation) determined using an anti-biotin antibody (Sigma).

For the isolation of biotinylated proteins, equal amounts of biotinylated RAW cell extract were treated with streptavidin-agarose and incubated at 4 °C for 4 h. The resin was extensively washed with a washing buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.7, containing 600 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1% β-octyl glucoside) before eluting them using SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 500 mm β-mercaptoethanol at 40 °C for 2 h. The eluted proteins were separated using SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The blots were probed with IKKβ antibody (Cell Signaling Technology) and immunodetected by chemiluminescence.

A549 Luciferase Reporter Assay

A549/NfκB-luc cells (Panomics; Quantitative Biology) harboring a luciferase reporter under the control of six consensus NF-κB binding motifs were propagated at 37 °C in the presence of 5% CO2 and in DMEM with 100 units/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. During the experiments, 105 cells were plated with 2 ml of medium and 100 μg/ml hygromycin in 12-well plates. Cells were treated with C3 for 4 h followed by TNFα (50 ng/ml) treatment for 6 h. Luciferase activity was measured in cell lysates using a commercial kit (Promega, Madison, WI). The luciferase activity was measured using a manual luminometer, and the data were normalized to the total protein concentration determined using the BCA protein assay.

Western Blots

A549 or RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in F-12k or DMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin, respectively. A549 (2 × 105) and RAW 264.7 (2.5 × 105) were plated in 35-mm plates, or 50,000 A549 cells were plated in 24-well plates on the day before the experiment. On the day of the experiment, the medium was replaced with fresh medium plus or minus varied concentrations of C3 for 4 h. In some experiments, the cells were also treated with MG132 (40 μm final) for 1 h. Following the pretreatments, the cells were treated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 5 min for the analysis of phospho-IκBα, IκBα, phospho-IKKα/β, and IKKβ and for 6 h for analysis of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) before quenching them with SDS-PAGE sample buffer containing 50 mm NaF. Samples were vortexed, boiled for 5 min, centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 min, and loaded onto a 10% precast SDS- polyacrylamide Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The blots were probed overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C and incubated with the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The signal was detected using a GE Healthcare ECL Plus chemiluminescence kit.

Wire Myography

Mice were anesthetized with diethyl ether. A thoracotomy was performed to expose thoracic and abdominal aorta. A 25-gauge syringe was inserted into the apex of the left ventricle and perfused free of blood with oxygenated Krebs Henseleit buffer. The right atrium was cut to provide an exit for blood. The aorta was removed and cleaned of fat and adventitia. The aorta was cut into 2-mm-long segments and mounted on a four-channel wire myograph (AD Instruments). Vessel rings were maintained in 10-ml organ baths with oxygenated PSS (95% O2 and 5% CO2) at 37 °C. Rings were allowed to equilibrate for 80 min with the buffer in each organ bath changed every 20 min. One gram of pretension was placed on each aortic ring (appropriate starting tension for optimal vasomotor function, as determined in previous experiments). An eight-channel octal bridge (Powerlab) and data acquisition software (Chart version 5.2.2) were used to record all force measurements. After equilibration for 80 min, 1 μm phenylephrine was added to each ring for submaximal contraction. After stabilization, either C3 or sodium nitroprusside (SNP) was added to the rings, and the tone of the rings was determined. For the determination of SNP and C3 dose-response relationships, aortic rings were precontracted with 10−6 m phenylephrine, and SNP or C3 was then added in increasing concentrations from 10−9 to 10−4 m.

Soluble Guanylyl Cyclase Assay

The cytosolic fraction of RAW264.7 cells (20 μl) was mixed with 40 μl of reaction buffer (50 mm triethanolamine, pH 7.4, 0.1 mm EGTA, 0.1 mg/ml creatine kinase, 200 μm phosphocreatine, 100 μm cGMP) and, when necessary, supplied with 50 μm C3 and incubated for 10 min at room temperature. The samples were then supplied with 50 μm GSNO and incubated for an additional 10 min. At the end of incubation, 0.3 μg of purified sGC was added to the sample, which was transferred to 37 °C, and the cyclase reaction was initiated by 1 mm GTP/[α-32P]GTP. After 10 min, the reaction was stopped by 0.5 ml of 150 mm zinc acetate, followed by the addition of 0.5 ml of 200 mm sodium carbonate. The formed zinc carbonate pellet containing the bulk of unreacted GTP was precipitated by 10 min of centrifugation at 15,000 × g, and the supernatant was loaded on a 1-ml alumina oxide column equilibrated with 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5. cGMP was eluted from the column with 10 ml of 50 mm Tris, pH 7.5, collected, and quantified by a scintillation counter.

RESULTS

Identification of Compounds That Specifically Inhibit GSNOR

A high throughput screening approach was used for identifying novel inhibitors of GSNOR. Screening for GSNOR inhibitors was performed in the presence of saturating and unsaturating concentrations of NAD+ and the alcohol substrate, octanol (18), to increase the probability of identifying compounds that bind only in the GSNO binding site of GSNOR. Three compounds (C1–C3), displaying high affinity and specificity for inhibiting GSNOR within the alcohol dehydrogenase family, were selected for further investigation (Tables 1 and S1). Each of the selected compounds obeyed Lipinski's rules (19) for druglike properties and had 2-order of magnitude lower IC50 than the present GSNOR inhibitor, dodecanoic acid (20) (Table 1).

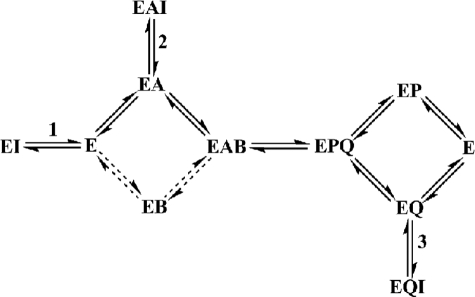

Dead end kinetic inhibition and fluorescence binding studies were performed to determine the mechanism by which C1–C3 inhibited GSNOR. As evident from Table 2 and supplemental Fig. S1, the inhibitors exhibit noncompetitive or uncompetitive inhibition against varied concentrations of GSNO or NADH. This suggested that neither of the substrates were able to completely prevent the compounds from binding to GSNOR. The inability of both of the substrates to overcome the inhibition completely is also consistent with C1–C3 binding to multiple enzyme complexes in the kinetic pathway (shown in Scheme 1). Inhibition by binding to a site outside the active site in GSNOR was unlikely, since the type of inhibition by the compounds against NADH and GSNOR would have been similar. An additional dead-end inhibition study involving dodecanoic acid as inhibitor against varied GSNO was performed to determine the type of complexes that an inhibitor binding in the substrate binding site (20, 21) would form in the kinetic pathway of GSNO reduction. Dodecanoic acid was found to be a noncompetitive inhibitor against varied concentrations of GSNO, although it binds into the GSNO binding site (Table 2). The noncompetitive inhibition of GSNOR by dodecanoic acid can be explained by its binding to GSNOR at more than one place in the kinetic pathway, one where it competes with GSNO to bind to the enzyme (steps 1 and 2 in Scheme 1) and one where GSNO does not normally bind in the kinetic pathway (step 3 in Scheme 1). The noncompetitive inhibition of GSNOR by C1–C3 against varied GSNO can also be explained by their forming such E·NADH·I (EAI in Scheme 1) and E·NAD+·I (EQI in Scheme 1) complexes. The uncompetitive inhibition by C1 and C3 and almost uncompetitive inhibition by C2 (although inhibition by C2 statistically fits the noncompetitive mechanism better, the Kis is 5-fold higher than Kii and has high S.E. values) against varied NADH can be explained by the compounds binding to the E·NADH complex in the nearly ordered kinetic mechanism of GSNOR and the high affinity of NADH (KD = 0.05 μm) for GSNOR (20). Both of these factors would make the contribution of E·I very small in the inhibition of the enzyme under the experimental conditions and make the inhibition uncompetitive. The mechanism by which C1–C3 inhibit GSNOR is similar to that by which the sulfoxide and amide compounds inhibit horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase (22). To summarize, the dead end kinetic inhibition studies are consistent with C1–C3 binding into the GSNO binding site and forming GSNOR·NADH·I (EAI in Scheme 1), GSNOR·NAD+·I (EQI), and GSNOR·I (EI) complexes.

TABLE 2.

Mechanism of inhibition of GSNOR by GSNOR inhibitors

The Kis and Kii are the slope and intercept inhibition constant estimates and are listed with their associated S.E. values. The data were fit to a competitive, noncompetitive (NC), or uncompetitive (UC) inhibition model. The type of inhibition shown represents the best fit of the data to the given model as judged from F statistics analysis.

| Compound | Varied substrate | Type of inhibition | Kis | Kii | KDa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | μm | |||

| C1 | GSNO | NC | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.3 |

| NADH | UC | 1.5 ± 0.1 | |||

| C2 | GSNO | NC | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.3 | 6.5 ± 1.0 |

| NADH | NC | 12 ± 5 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | ||

| C3 | GSNO | NC | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| NADH | UC | 1.7 ± 0.1 | |||

| Dodecanoic acid | GSNO | NC | 280 ± 40 | 190 ± 10 |

a KD is the equilibrium dissociation constant of the inhibitor for binding to the GSNOR·NADH complex, obtained by measuring the changes in the fluorescence of GSNOR-bound NADH with the addition of inhibitor (λex = 350 nm; λem = 455 nm). The dissociation constant was measured at 25 °C in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5. Each KD value is an average of three independent experiments and is shown with the associated S.E.

SCHEME 1.

Kinetic mechanism of GSNOR and the types of complexes formed by dodecanoic acid and the new GSNOR inhibitors in the kinetic pathway of GSNOR. GSNOR has a preferred pathway (shown by the heavy lines) through GSNOR·NADH complex (EA) in its random mechanism during the reduction of an aldehyde. The aldehyde (B), although it can bind to the free form of GSNOR (E), binds preferentially to the GSNOR·NADH complex to form the competent ternary complex (EAB). The ternary complex undergoes catalysis to form the products, NAD+ (Q) and alcohol (P). During the release of the products, either of the products can leave the enzyme. An inhibitor binding the GSNO binding site can bind to the free GSNOR (step 1), GSNOR·NADH (step 2), or GSNOR·NAD+ (step 3) binary complexes to form EI, EAI, and EQI complexes, respectively.

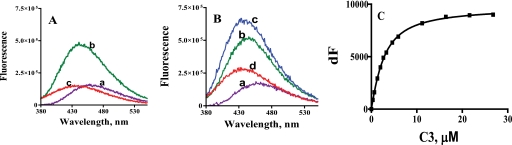

Equilibrium binding studies were conducted to support the findings of the kinetic dead end inhibition studies. The addition of C3 to the GSNOR·NADH binary complex resulted in the quenching as well as blue shift in NADH emission (compare curves b and c in Fig. 1 A). This is consistent with the formation of the GSNOR·NADH·C3 ternary complex. A similar quenching of the fluorescence of the coenzyme dihydropyridine ring was observed when the amide inhibitors were added to the horse liver ADH·NADH complex (23). Fluorescence binding studies were also conducted in the presence of the alcohol substrate, 12-hydroxydodecanoic acid (12-HDDA), to determine if C3 was excluding the substrate from the GSNOR active site. The formation of GSNOR·NADH·12-hydroxydodecanoate abortive ternary complex was reported earlier (20). Binding of 12-HDDA to the GSNOR·NADH complex resulted in an increase in the fluorescence of NADH, as shown in Fig. 1B (compare curves b and c). The addition of C3 to the mixture resulted in a spectrum (Fig. 1B, curve d) that was consistent with the displacement of 12-HDDA out of the active site and formation of the GSNOR·NADH·C3 ternary complex (curve d has higher fluorescence than that in Fig. 1A, curve c, because not all of 12-HDDA has been displaced by C3). These fluorescence binding experiments suggest that C3 excludes only the alcohol/aldehyde substrate from the binding site of GSNOR. C1 and C2 also exhibited similar effects on NADH fluorescence in the presence or absence of 12-HDDA, indicating that they too, like C3, only exclude the alcohol substrate from the GSNOR active site (data not shown). The fluorescence change observed upon the formation of the GSNOR·NADH·inhibitor complex was used to determine the equilibrium dissociation constant of the inhibitors for the GSNOR·NADH complex (Fig. 1C). The equilibrium dissociation constants of C1–C3 were in the low micromolar range (Table 2), suggesting that the affinity for the GSNOR·NADH complex was sufficient for the compounds to be effective inside the cells. C1 and C3 had a significantly higher affinity for the GSNOR·NADH complex than C2, as evident from their 3–5-fold lower equilibrium dissociation constants.

FIGURE 1.

The effect of C3 on the fluorescence of GSNOR bound NADH in the presence or absence of 12-HDDA. A, changes in the fluorescence of NADH (curve a) upon the sequential addition of GSNOR (curve b) and C3 (curve c). To a solution of 1.7 μm NADH were added 2 μm GSNOR and 50 μm C3 in sequence, and the fluorescence of the solution was measured each time (λex = 350 nm; λem = 375–550 nm). B, changes in the fluorescence of NADH (curve a) upon the sequential addition of GSNOR (curve b), 12-HDDA (curve c), and C3 (curve d). To a solution of 1.7 μm NADH were added 2 μm GSNOR, 810 μm 12-HDDA, and 50 μm C3 in sequence, and the fluorescence was measured each time (λex = 350 nm; λem = 375–550 nm). C, binding of C3 to GSNOR·NADH complex. The change in fluorescence of a 1.7 μm NADH and 2 μm GSNOR mixture (λex = 350 nm; λem = 455 nm) with increasing concentrations of C3 was fitted to a single-site binding model (Equation 1) using GraphPad Prism 4. The equilibrium dissociation constant of C3 was 1.9 ± 0.14 μm. All of the fluorescence studies were conducted at room temperature in 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 7.5.

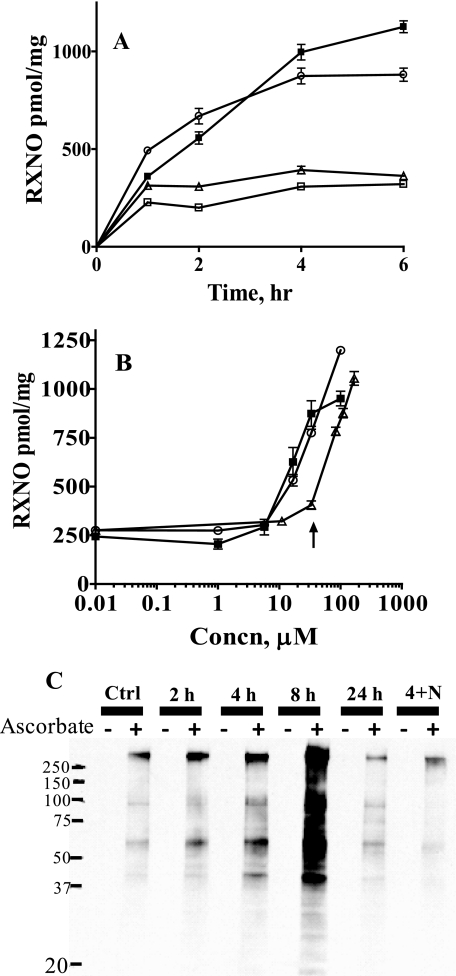

The ability of the newly discovered inhibitors to inhibit GSNOR inside the cells was tested using a murine macrophage cell line (RAW 264.7 cells). RAW 264.7 cells were treated with inhibitors alone or in combination with GSNO. The accumulation of intracellular SNOs was determined as a function of time and inhibitor concentration (Fig. 2, A and B). Significantly higher amounts of SNOs accumulated in cells treated with both GSNO and the inhibitor than in those treated with GSNO alone (Fig. 2A). C1 and C3 appeared to be more effective than C2 in inhibiting GSNOR inside the cells, as evident from higher accumulation of SNOs (Fig. 2, A and B). These studies demonstrate that C1–C3 are able to inhibit intracellular GSNOR. The dependence of SNO accumulation on the concentration of compounds in RAW 264.7 cells (Fig. 2B) suggested that it was possible to regulate the extent of S-nitrosylation with the GSNOR inhibitors. An analysis of the molecular size of the nitrosylated species inside the treated cells showed that more than 95% of the nitrosylated species were greater than 5 kDa in size. Furthermore, 21–28% of the nitrosylated species in treated cells were resistant to mercury pretreatment, suggesting that N-nitrosothiolated proteins were also getting formed inside the cells.

FIGURE 2.

Accumulation of nitrosothiols in RAW 264.7 cells upon GSNOR inhibition. A, effect of the length of incubation with C1–C3 on the buildup of nitrosylated species (RXNO) in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells, treated or untreated with 33 μm C1–C3 for 16 h, were transferred to a fresh medium containing 500 μm GSNO alone (□) or GSNO and 33 μm C1 (○), C2 (▵), or C3 (■). At the indicated times, the lysates were prepared and analyzed for nitroso species and protein concentration, using the chemiluminescence and Bradford assays, respectively. Data correspond to means ± S.E. (n = 6–21 wells), and p < 0.0001 by t test versus GSNO-treated cells for all measurements except for cells treated with GSNO and C2 for 6 h (p < 0.01). B, effect of the increasing concentrations of the compounds on the buildup of nitrosylated species (RXNO) in RAW 264.7 cells. RAW 264.7 cells were incubated with 500 μm GSNO in the presence of increasing concentrations of C1 (○), C2 (▵), or C3 (■). After 4 h, cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for nitroso species and protein concentration. Data correspond to means ± S.E. (n = 3–6 wells). The concentration of the compounds used in the time-dependent experiment (Fig. 2A) is shown by the arrow. C, regulation of S-nitrosylation in RAW 264.7 cells by GSNOR. RAW cells were treated with 33 μm C3 for varied lengths of time (0, 2, 4, 8, and 24 h) alone or in combination with 1.1 mm l-NAME for 4 h (lane 4+N). At the indicated times, the cells were quenched, and the lysate was analyzed for S-nitrosothiol content by the biotin switch assay. Equal amounts of proteins were loaded in each lane, and the degree of biotinylation (and hence S-nitrosylation) was determined using an anti-biotin antibody.

The effect of GSNOR inhibition on the nitrosylation of cellular proteins was also examined using the biotin switch assay technique developed by Jaffrey et al. (24) with modifications by Wang et al. (16). C3 increased the nitrosylation of cellular proteins in RAW 264.7 cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2C). The effects of C3 on the nitrosylation of cellular proteins appeared to peak around 8 h before coming down. The accumulation of SNOs was less if cells were simultaneously treated with C3 and the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor, l-NAME (Fig. 2C). These data suggested that the accumulation of SNOs in GSNOR-inhibited cells is dependent on NOS function and activity. The accumulation of SNOs in GSNOR-inhibited cells suggested that the inhibitors could be used to identify cellular processes regulated by GSNOR. The effects of GSNOR inhibition on two processes reported to be regulated by S-nitrosylation were examined. The effects of C3 on the activation of NF-κB by TNFα in cultured cells and on the tone of murine aorta were studied.

Suppression of NF-κB Activation by GSNOR Inhibition

NF-κB is a master regulator of the inflammatory response and exists in an inactive form in the cytoplasm complexed with a protein called IκB (inhibitor of κB) (26). Upon the arrival of a wide variety of stimuli, a kinase, IKKβ (inhibitor of κB kinase β) is activated by phosphorylation and in turn phosphorylates IκB. Phosphorylated IκB (p-IκB) is targeted for ubiquitin-dependent proteosomal degradation, setting NF-κB free to initiate the transcription of inflammatory genes (26). Nitric oxide and NF-κB regulate each other's activity, as evident from the presence of NF-κB response elements in NOS2 promoter region and the suppression of NF-κB activity by S-nitrosylation (3, 27–29). IKKβ has been shown to be the most upstream target of NO-mediated S-nitrosylation in the NF-κB signaling pathway (28). S-Nitrosylation of IKKβ inhibits its kinase activity and suppresses NF-κB activation. To determine if IKKβ was among the proteins undergoing S-nitrosylation in the presence of C3, we performed the biotin switch assay on the cytosolic proteins from RAW 264.7 cells treated with C3. The presence of a higher amount of biotinylated IKKβ in the labeling mixture containing ascorbate versus the no ascorbate control (Fig. 3A) suggested that IKKβ was S-nitrosylated in cells treated with C3. The S-nitrosylation of IKKβ appeared to be dependent on the activity of nitric-oxide synthases, since co-incubation of the cells with C3 and nitric-oxide synthase inhibitor, l-NAME, decreased its nitrosylation (lane 4h+N versus 4h in Fig. 3A). This result suggested that nitric-oxide synthase products nitrosylate IKKβ, whereas GSNOR regulates the extent and turnover of S-nitrosylation of IKKβ. Since nitrosylation of IKKβ inhibits its kinase activity, the effect of C3 on the phosphorylation of IκB by IKKβ was studied. As evident in Fig. 3B, the amount of TNFα-induced phosphorylation of IκB was decreased in cells pretreated with C3. The extent of phosphorylation decreased further with increasing concentrations of C3. This suggested that the inhibition of IKKβ increased with the extent of GSNOR inhibition.

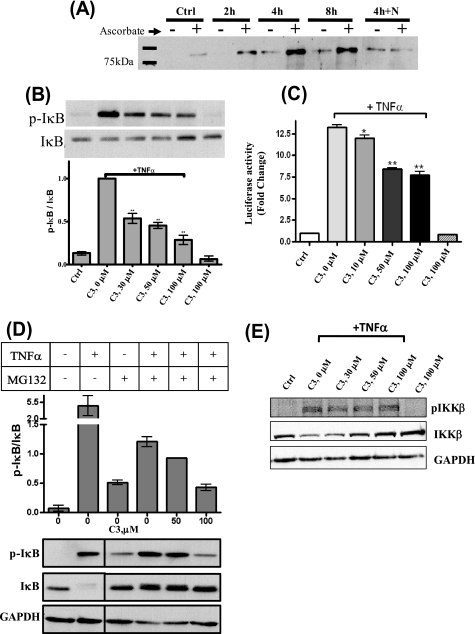

FIGURE 3.

Suppression of NF-κB activation by C3. A, induction of S-nitrosylation of IKKβ in RAW cells by C3. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with C3 (33 μm) for varied lengths of time, either alone (2, 4, and 8 h) or in combination with 1.1 mm l-NAME for 4 h (4h+N) and analyzed for S-nitrosylation using the biotin switch assay. Equal amounts of biotinylated cell extract from each sample were subjected to streptavidin purification and Western blotted using IKKβ antibody. The specificity of the biotin switch assay was demonstrated using no ascorbate controls. B, inhibition of TNFα-induced phosphorylation of IκB in RAW 264.7 cells in the presence of C3. RAW 264.7 cells were treated with varied concentrations of C3 (0, 30, 50, and 100 μm) for 4 h before being activated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 5 min. The cell extract was analyzed by Western blot using p-IκB and IκB antibodies. Controls involving untreated cells (Ctrl) or those treated with 100 μm C3 alone were also performed concomitantly. The ratios (mean ± S.E.) of the intensities of p-IκB and IκB are shown (n = 3; **, p < 0.001). C, suppression of NF-κB-dependent gene transcription by C3 in A549 cells. A549 cells harboring a NF-κB-dependent luciferase reporter were treated with varied concentrations of C3 (0, 10, 50, and 100 μm) for 4 h before being stimulated with TNFα (50 ng/ml) for 6 h. Following the incubation period, the cell extract was tested for luciferase activity, and the mean ± S.E. -fold change in luciferase activity over untreated cells was determined (n = 4; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001). D, inhibition of TNFα-induced activation of IKKβ in A549 cells by C3. A549 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of C3 for 4 h in the presence of MG132 (1-h incubation) before being activated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 5 min. The cell extract was subjected to Western blot using p-IκB, IκB, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) antibodies. The ratios (mean ± range; n = 2) of the intensities of p-IκB and IκB are shown. E, C3 does not affect TNFα-induced phosphorylation of IKKβ in A549 cells. A549 cells, treated or untreated with the indicated concentration of C3 for 4 h, were activated with TNFα for 5 min and quenched for Western blot analysis using p-IKKβ antibody.

We also studied the effect of C3 on the TNFα-induced activation of IKKβ and, subsequently, NF-κB in A549 lung epithelial cells (Figs. 3 (C–E) and 4 and supplemental Fig. S2). In an NF-κB reporter assay performed in A549 cells expressing luciferase under the control of six NF-κB response elements, C3 reduced the TNFα-induced NF-κB activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3C). Since the induction of NF-κB activity by TNFα is dependent upon IKKβ activity (30), phosphorylation of IκB was studied to determine if IKKβ was inhibited in the A549 cells pretreated with C3. The total amount of IκB was significantly higher in cells pretreated with C3 (Fig. S2), suggesting that the rate of degradation of IκB was significantly lower in these cells. Lower amounts of phospho-IκB were also found in cells treated with both C3 and the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (31) (Fig. 3D). This suggested that the higher levels of IκB observed in cells pretreated with C3 (supplemental Fig. S2) were due to a decrease in the rate of the phosphorylation of IκB rather than a decrease in the rate of proteasomal phospho-IκB degradation. Together, these results suggested that in C3-treated cells, IKKβ was inhibited. However, the observed suppression of NF-κB activation as measured in the luciferase assay could also have been potentiated by S-nitrosylation of the p65 and p50 subunits of NF-κB. S-Nitrosocysteine has been reported to nitrosylate the p65 and p50 subunits of NF-κB and inhibit their transactivation property (3, 32).

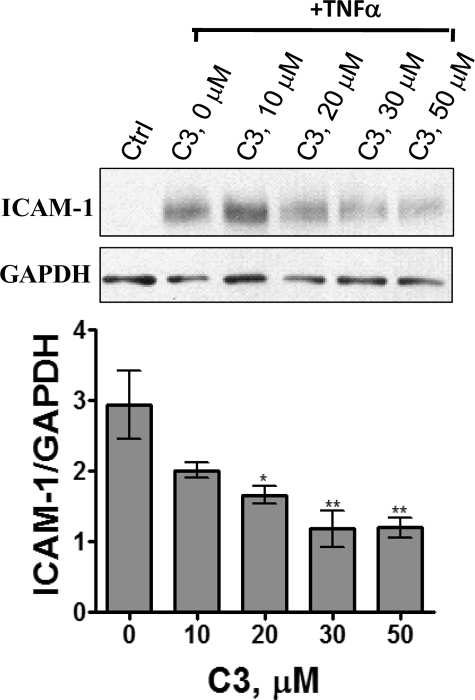

FIGURE 4.

Concentration-dependent inhibition of TNFα-induced expression of ICAM-1 by C3. A549 cells, treated with varied concentrations of C3 for 4 h were stimulated with TNFα (10 ng/ml) for 6 h before quenching the cells and analyzing the cell extract by Western blot analysis using ICAM-1 and GAPDH antibodies. The band intensities of ICAM-1 and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were determined by densitometry. The graph shows the mean ± S.E. of the ratio (n = 4; *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01).

We also examined the effects of C3 on the phosphorylation of IKKβ and its kinase activity to rule out other mechanisms of inhibition of IKKβ. As shown in Fig. 3E, the extent of IKKβ phosphorylation was similar in cells treated with TNFα alone and those treated with C3 and TNFα. This suggested that C3 does not affect any of the proteins involved in the activation of IKKβ by TNFα. C3 also had no significant effect on the kinase activity of IKKβ (supplemental Fig. S3). This suggested that inhibition of IKKβ did not result from any direct interaction between C3 and IKKβ. Together, the data are consistent with the nitrosylation-induced inhibition of IKKβ in C3-treated cells.

The suppression of NF-κB activity by C3 in A549 cells was also studied by determining the amount of ICAM-1 expressed in response to TNFα. ICAM-1 is one of the proinflammatory proteins induced by NF-κB (33). C3 decreased the expression of ICAM-1 in response to TNFα in a dose-dependent manner in A549 cells (Fig. 4). This is consistent with the suppression of NF-κB mediated gene expression in C3-treated cells.

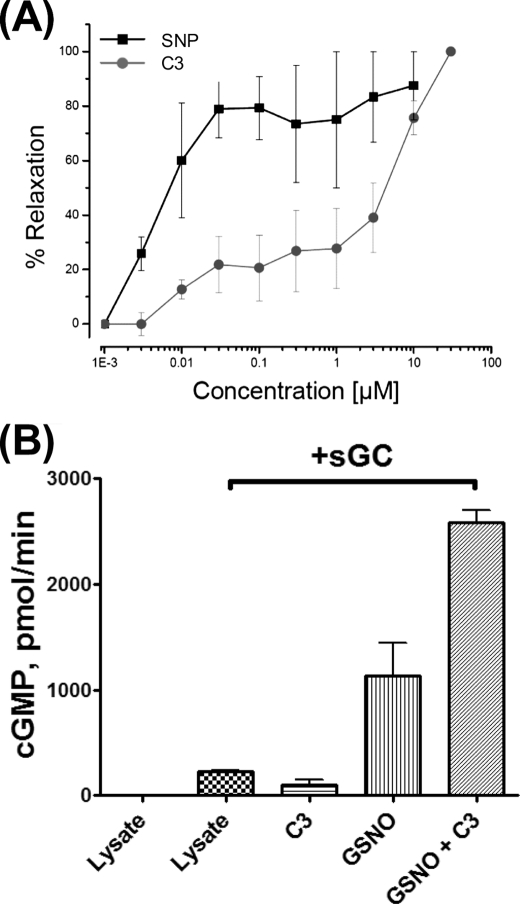

Relaxation of Murine Aorta by GSNOR Inhibition

Nitric oxide-dependent regulation of vascular tone is mediated through the activation of sGC (34). S-Nitrosothiols, through decomposition to NO, have been shown to mediate the activation of sGC and relax smooth muscles (35). Treatment with C3 (50 μm) completely relaxed the preconstricted segments of murine aorta within 15 min (supplemental Fig. S4). A complete concentration-response curve revealed an EC50 of 5 μm for C3 (Fig. 5A), with as little as 300 nm giving ∼10% relaxation. Direct comparison with SNP revealed that C3 was less potent than SNP at relaxing the vascular smooth muscle (Fig. 5A). This suggested that GSNOR-regulated S-nitrosothiols were involved in the regulation of vascular tone. To determine if stimulation of sGC was involved during the relaxation of aorta rings by C3, the effect of C3 on cGMP production by sGC was studied in vitro. The addition of GSNO to RAW 264.7 cell lysate supplemented with recombinant sGC resulted in a stimulation of cGMP production (Fig. 5B). These data are consistent with an earlier report on the relaxation of smooth muscles by GSNO through the release of nitric oxide (36). In the presence of C3, the stimulation of cGMP production by GSNO more than doubled, suggesting that GSNOR-mediated decomposition of GSNO limits the amount of nitric oxide released from S-nitrosothiols for the stimulation of sGC. Collectively, these data demonstrate that inhibiting nitrosothiol breakdown activates and enhances the NO-cGMP pathway.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of C3 on the function of NO/cGMP pathway. A, C3 induces vascular relaxation. Mouse aorta segments were equilibrated in oxygenated PSS (95% O2 and 5% CO2) at 37 °C. Following equilibration, 1 μm phenylephrine was added to each ring for submaximal contraction. After stabilization, increasing concentrations (0–100 μm) of either C3 or SNP were added to the rings, and the response to agonist was determined as a percentage of maximal relaxation. B, C3 potentiates the activation of sGC by nitrosoglutathione. RAW cell lysate, which has GSNOR activity but lacks sGC, was supplied with recombinant sGC protein and preincubated for 10 min with 50 μm C3 or buffer. After the addition of 50 μm GSNO or phosphate-buffered saline vehicle, GMP synthesis was measured by direct [α-32P]GTP → cGMP conversion, as described previously (25).

DISCUSSION

The central role of S-nitrosylation in the cellular effects of nitric oxide is increasingly being realized as reports of proteins regulated by S-nitrosylation continue to grow. SNOs are both the end products of the nitric oxide signaling pathway and the carriers of nitric oxide. Regulating the levels of SNOs should regulate nitric oxide bioactivity. Our studies reveal that denitrosylation affected by GSNOR limits the NO-mediated activation of guanylyl cyclase and the suppression of NF-κB. The three inhibitors described herein will allow determination of the processes regulated by GSNOR through S-nitrosylation and allow examination of the therapeutic benefit of inhibiting GSNOR. The suppression of NF-κB activation in RAW 264.7 and A549 cells and the relaxation of murine aorta by C3 suggest the possibility of regulating immune response and the tone of smooth muscles simultaneously via GSNOR inhibition. Similar to phosphodiesterase inhibitors, such as sildenafil, the action of these compounds requires some production of NO from NOS.

The accumulation of nitrosothiols in RAW 264.7 cells treated with C3 suggests GSNOR to be actively regulating the turnover and metabolism of S-nitrosothiols inside the cells. Due to the large number of proteins shown to be affected by S-nitrosylation, and the number of enzymes shown to effect denitrosylation, the cellular effects of GSNOR inhibitors will depend on the identity of the proteins getting nitrosylated and the time period over which that occurs. It also became evident that the effects of the GSNOR inhibition are not immediate, and the effect on the cellular processes correlates with the accumulation of S-nitrosylated protein(s) or release of NO from SNOs. In case of suppression of NF-κB activation, pretreatment of the cells with the C3 was essential. Similarly, the relaxation of murine aorta by C3 occurred after a period of time. Thus, the effects of GSNOR inhibition are likely to come into effect slowly.

The exclusion of GSNO from its binding site and inhibition of GSNOR at multiple places in its kinetic pathway by C1–C3 is advantageous for the in vivo inhibition of GSNOR. GSNOR substrates would not be able to prevent C1–C3 from binding GSNOR and overcome inhibition. By virtue of not binding in the coenzyme binding site, C1–C3 have a high probability of specifically inhibiting GSNOR among the NAD(H) binding dehydrogenases. Although they are structurally diverse, C1–C3 each has a free carboxyl group like most substrates for GSNOR. Given the importance of Arg115 at the base of the GSNOR active site in the binding of GSNO and S-hydroxymethyl-glutathione (37, 38), it is very likely that the free carboxyl group in C1–C3 interacts with Arg115. In summary, we report novel tools that regulate GSNOR function inside the cells that will allow exploration of the cellular and pharmacological effects of inhibiting an important nitric oxide deactivation pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Maureen Harrington, Robert A. Harris, and William F. Bosron for critically reading the manuscript. We thank the Indiana Genomics Initiative (INGEN®) Protein Expression Core of Indiana University (supported in part by Lilly Endowment Inc.) for the expression and purification of enzymes.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R21HL087816 (to P. C. S. and S. P. S.) and R01HL088128 (to E. M.). This work was also supported by the Showalter Research trust (to P. C. S. and S. P. S.), the Research Support Funds Grant (to P. C. S.), and the American Heart Association-National (to N. S. B.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S4.

- NO

- nitric oxide

- SNO

- S-nitrosothiol

- GSNOR

- S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase

- GSNO

- S-nitrosoglutathione

- ADH

- alcohol dehydrogenase

- sGC

- soluble guanylyl cyclase

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- ICAM

- intercellular adhesion molecule

- SNP

- sodium nitroprusside

- 12-HDDA

- 12-hydroxydodecanoic acid

- p-IκB

- phosphorylated IκB

- l-NAME

- N (ω) nitro-l-arginine methyl ester.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hess D. T., Matsumoto A., Kim S. O., Marshall H. E., Stamler J. S. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 150–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benhar M., Stamler J. S. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 645–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelleher Z. T., Matsumoto A., Stamler J. S., Marshall H. E. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30667–30672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Que L. G., Liu L., Yan Y., Whitehead G. S., Gavett S. H., Schwartz D. A., Stamler J. S. (2005) Science 308, 1618–1621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whalen E. J., Foster M. W., Matsumoto A., Ozawa K., Violin J. D., Que L. G., Nelson C. D., Benhar M., Keys J. R., Rockman H. A., Koch W. J., Daaka Y., Lefkowitz R. J., Stamler J. S. (2007) Cell 129, 511–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benhar M., Forrester M. T., Hess D. T., Stamler J. S. (2008) Science 320, 1050–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson M. A., Macdonald T. L., Mannick J. B., Conaway M. R., Gaston B. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39872–39878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trujillo M., Alvarez M. N., Peluffo G., Freeman B. A., Radi R. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 7828–7834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wink D. A., Cook J. A., Kim S. Y., Vodovotz Y., Pacelli R., Krishna M. C., Russo A., Mitchell J. B., Jourd'heuil D., Miles A. M., Grisham M. B. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11147–11151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu L., Hausladen A., Zeng M., Que L., Heitman J., Stamler J. S. (2001) Nature 410, 490–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu L., Yan Y., Zeng M., Zhang J., Hanes M. A., Ahearn G., McMahon T. J., Dickfeld T., Marshall H. E., Que L. G., Stamler J. S. (2004) Cell 116, 617–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eklund H., Müller-Wille P., Horjales E., Futer O., Holmquist B., Vallee B. L., Höög J. O., Kaiser R., Jörnvall H. (1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 193, 303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samouilov A., Zweier J. L. (1998) Anal. Biochem. 258, 322–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y., Hogg N. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 7891–7896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffrey S. R. (2005) Methods Enzymol. 396, 105–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X., Kettenhofen N. J., Shiva S., Hogg N., Gladwin M. T. (2008) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44, 1362–1372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y., Keszler A., Broniowska K. A., Hogg N. (2005) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 874–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estonius M., Höög J. O., Danielsson O., Jörnvall H. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 15080–15085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lipinski C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeney P. J. (2001) Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 46, 3–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanghani P. C., Stone C. L., Ray B. D., Pindel E. V., Hurley T. D., Bosron W. F. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 10720–10729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanghani P. C., Robinson H., Bosron W. F., Hurley T. D. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 10778–10786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chadha V. K., Leidal K. G., Plapp B. V. (1983) J. Med. Chem. 26, 916–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarma R. H., Woronick C. L. (1972) Biochemistry 11, 170–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jaffrey S. R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Ferris C. D., Tempst P., Snyder S. H. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin E., Lee Y. C., Murad F. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 12938–12942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2008) Cell 132, 344–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marshall H. E., Hess D. T., Stamler J. S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8841–8842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reynaert N. L., Ckless K., Korn S. H., Vos N., Guala A. S., Wouters E. F., van der Vliet A., Janssen-Heininger Y. M. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8945–8950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kolios G., Valatas V., Ward S. G. (2004) Immunology. 113, 427–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Q., Verma I. M. (2002) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 725–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Z., Hagler J., Palombella V. J., Melandri F., Scherer D., Ballard D., Maniatis T. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 1586–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall H. E., Stamler J. S. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 1688–1693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newton R., Holden N. S., Catley M. C., Oyelusi W., Leigh R., Proud D., Barnes P. J. (2007) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 321, 734–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Arnold W. P., Mittal C. K., Katsuki S., Murad F. (1977) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 74, 3203–3207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ignarro L. J., Edwards J. C., Gruetter D. Y., Barry B. K., Gruetter C. A. (1980) FEBS Lett. 110, 275–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathews W. R., Kerr S. W. (1993) J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 267, 1529–1537 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanghani P. C., Bosron W. F., Hurley T. D. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 15189–15194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Engeland K., Höög J. O., Holmquist B., Estonius M., Jörnvall H., Vallee B. L. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 2491–2494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.