Abstract

Homologous recombination represents an important means for the error-free elimination of DNA double-strand breaks and other deleterious DNA lesions from chromosomes. The Rad51 recombinase, a member of the RAD52 group of recombination proteins, catalyzes the homologous recombination reaction in the context of a helical protein polymer assembled on single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) that is derived from the nucleolytic processing of a primary lesion. The assembly of the Rad51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament, often referred to as the presynaptic filament, is prone to interference by the single-strand DNA-binding factor replication protein A (RPA). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rad52 protein facilitates presynaptic filament assembly by helping to mediate the displacement of RPA from ssDNA. On the other hand, disruption of the presynaptic filament by the Srs2 helicase leads to a net exchange of Rad51 for RPA. To understand the significance of protein-protein interactions in the control of Rad52- or Srs2-mediated presynaptic filament assembly or disassembly, we have examined two rad51 mutants, rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D, that are simultaneously ablated for Rad52 and Srs2 interactions and one, rad51 A320V, that is differentially inactivated for Rad52 binding for their biochemical properties and also for functional interactions with Rad52 or Srs2. We show that these mutant rad51 proteins are impervious to the mediator activity of Rad52 or the disruptive function of Srs2 in concordance with their protein interaction defects. Our results thus provide insights into the functional significance of the Rad51-Rad52 and Rad51-Srs2 complexes in the control of presynaptic filament assembly and disassembly. Moreover, our biochemical studies have helped identify A320V as a separation-of-function mutation in Rad51 with regards to a differential ablation of Rad52 interaction.

Homologous recombination (HR)3 helps maintain genomic stability by eliminating DNA double-strand breaks induced by ionizing radiation and chemical reagents, by restarting damaged or collapsed DNA replication forks, and by elongating shortened telomeres especially when telomerase is dysfunctional (1–3). Accordingly, defects in HR invariably lead to enhanced sensitivity to genotoxic agents, chromosome aberrations, and tumor development (4, 5). In meiosis also, HR helps mediate the linkage of homologous chromosome pairs via arm cross-overs, thus ensuring the proper segregation of chromosomes at the first meiotic division (6). Accordingly, HR mutants exhibit a plethora of meiotic defects, including early meiotic cell cycle arrest, aneuploidy, and inviability.

Much of the knowledge regarding the mechanistic basis of HR has been derived from studies of model organisms, such as the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetic analyses in S. cerevisiae have led to the identification of the RAD52 group of genes, namely, RAD50, RAD51, RAD52, RAD54, RAD55, RAD57, RAD59, RDH54, MRE11, and XRS2 (1), that are needed for the successful execution of HR. Each member of the RAD52 group of genes has an orthologue in higher eukaryotes, including humans, and mutations in any of these genes cause defects in HR and repair of double-strand breaks.

The DNA pairing and strand invasion step of the HR reaction is mediated by RAD51-encoded protein, which is orthologous to the Escherichia coli recombinase RecA (2). Like RecA, Rad51 polymerizes on ssDNA, derived from the nucleolytic processing of a primary lesion such as a double-strand break, to form a right-handed nucleoprotein filament, often referred to as the presynaptic filament (3, 7). The presynaptic filament engages dsDNA, conducts a search for homology in the latter, and catalyzes DNA joint formation between the recombining ssDNA and dsDNA partners upon the location of homology (1, 3). As such, the timely and efficient assembly of the presynaptic filament is indispensable for the successful execution of HR.

Because the nucleation of Rad51 onto ssDNA is a rate-limiting process, presynaptic filament assembly is prone to interference by the single-strand DNA-binding protein replication protein A (RPA) (1, 3, 7). In reconstituted biochemical systems, the addition of Rad52 counteracts the inhibitory action of RPA (8, 9). Consistent with the biochemical results, in both mitotic and meiotic cells, the recruitment of Rad51 to double-strand breaks is strongly dependent on Rad52 (10–12). This effect of Rad52 on Rad51 presynaptic filament assembly has been termed a “recombination mediator” function (13).

Interestingly, genetic studies have shown that the Srs2 helicase fulfills the role of an anti-recombinase. Specifically, mutations in Srs2 often engender a hyper-recombinational phenotype and can also help suppress the DNA damage sensitivity of rad6 and rad18 mutants, because of the heightened HR proficiency being able to substitute for the post-replicative DNA repair defects of these mutant cells (2, 14). Importantly, in reconstituted systems, Srs2 exerts a strong inhibitory effect on Rad51-mediated reactions in a manner that is potentiated by RPA. Biochemical and electron microscopic analyses have provided compelling evidence that Srs2 acts by disassembling the presynaptic filament, to effect the replacement of Rad51 by RPA (15, 16). The ability of Srs2 to dissociate the presynaptic filament relies on its ATPase activity, revealed using mutant variants, K41A and K41R, that harbor changes in the Walker type A motif involved in ATP engagement. Accordingly, the srs2 K41A and srs2 K41R mutants are biologically inactive (17).

In both yeast two-hybrid and biochemical analyses, a complex of Rad51 with either Rad52 or Srs2 can be captured (1, 16). Using yeast two-hybrid-based mutagenesis, several rad51 mutant alleles, A320V, Y388H, and G393D, that engender a defect in the yeast two-hybrid association with Rad52 have been found (18). Here we document our biochemical studies demonstrating the inability of these rad51 mutant proteins to physically and functionally interact with Rad52. Interestingly, we find that two of these rad51 mutants, namely, Y388H and G393D, are also defective in Srs2 interaction. Accordingly, these mutant rad51 proteins form presynaptic filaments that are resistant to the disruptive action of Srs2. Our results thus emphasize the role of Rad51-Rad52 and Rad51-Srs2 interactions in the regulation of Rad51 presynaptic filament assembly and maintenance, and they also reveal the presence of overlapping Rad52 and Srs2 interaction motifs in Rad51. In these regards, our biochemical studies have identified the A320V change as a separation-of-function mutation in Rad51.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Purification of Proteins

All of the chromatographic steps in protein purification were carried out at 4 °C. The rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, and rad51 G393D proteins were expressed in yeast cells and purified to near homogeneity, as described for the wild type counterpart (19). Rad52 with a His6 tag at its C terminus and Srs2 with a His9 tag at its N terminus were expressed in E. coli Rosetta strains (Novagen) and purified to near homogeneity, as described (16, 20). Rad54 and Rdh54 containing a thioredoxin-His6 double tag at its N terminus were purified from Rosetta cells, as described (21, 22).

For the expression and purification of Rad52-C, a DNA fragment harboring amino acid residues 327–504 of Rad52 was introduced into pET-11d. Rosetta cells harboring this plasmid were grown at 37 °C to A600 0.6–0.8, at which time 0.4 mm isopropyl d-thiogalactopyranoside was added. The culture was incubated for another 3 h at 37 °C, and the cells were harvested by centrifugation. Cell lysate from 20 g of cells (being equivalent to 10 liters of culture) was prepared by sonicating the cell suspension in 50 ml of cell breakage buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mm KCl, 2 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 10% sucrose, 0.01% Igepal, 5 μg/ml leupeptin, pepstatin A, aprotinin, chymostatin, and 0.4 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and ultracentrifugation (100,000 × g for 90 min). The clarified lysate was applied onto a Q Sepharose column (20 ml), and the flow-through fraction was collected and applied onto a SP Sepharose column (20 ml). The proteins were fractionated with a 160-ml gradient from 50 to 300 mm KCl in K buffer (10 mm K2HPO4, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 1 mm DDT, and 0.5 mm EDTA). The fractions containing Rad52-C (8 ml total, 200 mm KCl) were applied onto a Macro-Hydroxyapatite column (1 ml; Bio-Rad) and then eluted with a 40-ml gradient from 0 to 200 mm KH2PO4 in K buffer. The Macro-Hydroxyapatite fractions (6 ml total, 60 mm KH2PO4) were applied onto 1-ml Mono S column and eluted with a 40-ml gradient from 50 to 300 mm KCl in K buffer. The peak fractions (5 ml total, 150 mm KCl) were collected and concentrated to 10 mg/ml with Amicon Ultra-4 concentrator (Millipore). The overall yield of highly purified Rad52-C was ∼1.5 mg.

In Vitro Pulldown Assay

Rad51 or rad51 mutant (5.0 μm) was mixed with Rad52 (5.0 μm), Rad54 (5.0 μm), or Srs2 (5.0 μm) at 4 °C for 30 min in 30 μl of buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm KCl, 10 mm imidazole, 1 mm β-mercaptoethanol, 0.01% Igepal). To examine the effect of Rad52 on Rad51-Srs2 complex formation, Rad51 or rad51 A320V (5.0 μm) was mixed with Rad52-C (3.3, 5.0, or 6.7 μm) and Srs2 (5.0 μm), as above. The reactions were gently mixed at 4 °C for 30 min with 20 μl of Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen), which binds the polyhistidine tag on Rad52, Rad54, or Srs2, to capture protein complexes. After washing the resin three times with 20 μl of the same buffer, the bound proteins were eluted with 2% SDS. The supernatant (S), wash (W), and SDS eluate (E) fractions, 10 μl each, were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue.

DNA Substrates

The ϕX174 replicative form I DNA and viral (+) strand DNA were purchased from New England Biolabs. The linear ϕX174 dsDNA was prepared by digesting the replicative form I DNA with the restriction enzyme ApaLI. Topologically relaxed ϕX174 DNA was prepared by treating the replicative form I DNA with calf thymus topoisomerase I (Invitrogen) as described previously (23). For the DNA mobility shift assay, the 83-mer oligonucleotide (5′-TTTATATCCTTTACTTTATTTTCTATGTTTATTCATTTACTTATTTTGTATTATCCTTATACTTTTTACTTTATGTTCATTT-3′) was 5′ end-labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Roche Applied Science) and [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham Biosciences). The radiolabeled oligonucleotides were annealed to its exact complement by heating the two oligonucleotides at 85 °C for 3 min followed by slow cooling to 23 °C. The resulting duplex DNA was purified from a 10% polyacrylamide gel, as described (22). For the D-loop assay, a 5′ end-labeled 90-mer oligonucleotide complementary to positions 1932–2022 of pBluescript SK DNA was used (24). The 150-mer oligonucleotide (5′-TCTTATTTATGTCTCTTTTATTTCATTTCCTATATTTATTCCTATTATGTTTTATTCATTTACTTATTCTTTATGTTCATTTTTTATATCCTTTACTTTATTTTCTCTGTTTATTCATTTACTTATTTTGTATTATCCTTATCTTATTTA-3′) was used as DNA substrate in the electron microscopic analysis of presynaptic filament formation.

ATPase Assay

Rad51 or rad51 mutant (3.5 μm) was incubated with ϕX174 circular (+) strand DNA (30 μm nucleotides) in 10 μl of buffer (35 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 50 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 0.1 mm [γ-32P]ATP) at 37 °C. A 2-μl aliquot of the reaction mixtures was removed at the indicated times and mixed with an equal volume of 500 mm EDTA to halt the reaction. Thin layer chromatography and phosphorimaging analysis were used to determine the level of ATP hydrolysis, as described (25).

DNA Mobility Shift Assay

The 32P-labeled 83-mer ssDNA or dsDNA (4.5 μm nucleotides) was mixed with the indicated amounts of Rad51 or rad51 mutant in 10 μl of buffer (35 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin) for 10 min at 37 °C. The reaction mixtures were resolved in 10% polyacrylamide gels in TA buffer (30 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.4) containing 5 mm magnesium acetate. The gels were dried on a sheet of DEAE paper (Whatman) and subjected to phosphorimaging analysis.

Assays for Rad51-induced DNA Topology Change

To measure DNA topology change induced by Rad51 or the rad51 mutants, the indicated amount of the wild type or mutant protein was incubated with topologically relaxed ϕX174 dsDNA (15 μm nucleotides) for 5 min at 37 °C in 8.1 μl of buffer (35 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 100 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, 2 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin), followed by the incorporation of 3 units of calf thymus topoisomerase I (Invitrogen; added in 0.4 μl) and a 20-min incubation. To measure the disruption of the presynaptic filament by Srs2, Rad51 or rad51 mutant (2 μm) was incubated with ϕX174 ssDNA (8.5 μm nucleotides) for 5 min with an ATP regenerating system (20 mm creatine phosphate and 20 μg/ml creatine kinase) in 8.1 μl of buffer, followed by the incorporation of RPA (1 μm, added in 0.5 μl) and Srs2 (35 or 50 nm, added in 0.7 μl) and a 5-min incubation. Topologically relaxed ϕX174 dsDNA (15 μm nucleotides) and 3 units of calf thymus topoisomerase I (Invitrogen) were then added in 0.7 and 0.4 μl, respectively, followed by an 8-min incubation. The reaction mixtures were deproteinized with SDS (0.5%) and proteinase K (0.5 mg/ml) for 5 min at 37 °C, before being resolved on 0.9% agarose gel run in TAE buffer (30 mm Tris acetate, pH 7.4, 0.5 mm EDTA). DNA species were stained with ethidium bromide, and the results were recorded in a gel documentation station (Bio-Rad).

DNA Strand Exchange Assay

All of the reaction steps were carried out at 37 °C. For the standard reaction, the indicated amount of Rad51 or rad51 mutant was incubated with ϕX174 ssDNA (30 μm nucleotides) in 10.3 μl of buffer (35 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, 2.5 mm ATP, 3 mm MgCl2) at 37 °C for 5 min. Following the addition of RPA (1.2 μm, added in 0.5 μl), linearized ϕX174 dsDNA (25 μm nucleotides, added in 0.7 μl) and spermidine hydrochloride (final concentration, 4 mm added in 1 μl) were incorporated into the reaction, followed by a 60-min incubation. After deproteinizing treatment, the reaction mixtures were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and analyzed as before. To examine the effects of the rad51 mutations, Rad51 or rad51 mutant (10 μm), RPA (2 μm), and the indicated amounts of Rad52 were mixed on ice for 10 min in buffer before adding ssDNA and a 10-min incubation. Otherwise, these reactions were treated and processed in the same manner as above.

D-loop Reaction

The radiolabeled 90-mer oligonucleotide (3 μm nucleotides) was incubated with Rad51 or rad51 mutant (1 μm) for 5 min at 37 °C in 10 μl of buffer (35 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.2, 140 mm KCl, 2 mm ATP, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, and the ATP-regenerating system) to assemble the Rad51-ssDNA nucleoprotein filament, followed by the incorporation of RPA (200 nm, added in 0.5 μl) and Srs2 (17 or 24 nm, added in 0.5 μl) and a 4-min incubation at 37 °C. Then Rad54 (150 nm) was added in 0.5 μl, and the reaction mixtures were incubated for 3 min at 23 °C. DNA pairing was initiated by adding pBluescript replicative form I DNA (50 μm base pairs) in 1 μl, and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 30 °C for 7 min. The reaction mixtures were deproteinized and subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis, as above, and the gels were dried and subjected to phosphorimaging analysis.

Electron Microscopy

To assemble the presynaptic filament, the 150-mer oligonucleotide (7.2 μm nucleotides) and Rad51 or rad51 G393D (2.4 μm) were incubated for 5 min in 12 μl of buffer containing 2 mm ATP, 2.5 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, and an ATP-regenerating system at 37 °C. Following the addition of RPA (240 nm, in 0.5 μl) and Srs2 (100 nm, in 0.4 μl), the reaction mixture was incubated for 3 min at 37 °C. After a 10-fold dilution with buffer, a 3-μl aliquot of the reaction was applied to a 400-mesh grid coated with carbon film, which had been glow-discharged in air. The grid was stained with 2% uranyl acetate for 30 s and rinsed with water. The samples were examined with a Tecnai 12 Biotwin electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a tungsten filament at 100 keV. Digital images were captured with a Morada (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions) charge-coupled device camera at a nominal magnification of 87,000–135,000×.

RESULTS

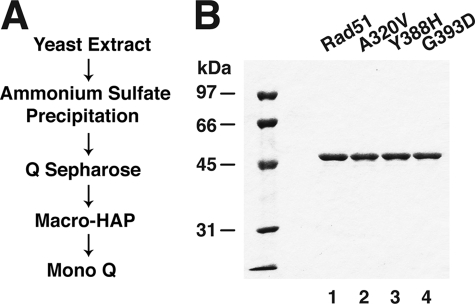

Purification of rad51 Mutants

A mutagenic screen conducted previously identified three RAD51 mutations, namely, A320V, Y388H, and G393D, that ablate the interaction of Rad51 with Rad52 but not with Rad54 or Rad55 in the yeast two-hybrid system (18). For their biochemical analyses, we expressed the three rad51 mutant proteins alongside the wild type counterpart in yeast cells deleted for the endogenous RAD51 gene and purified these proteins to near homogeneity (Fig. 1) using the procedure devised for the wild type protein (19). The mutants were expressed to the same level as the wild type protein, and during purification, all three mutants behaved like the wild type protein chromatographically. Moreover, a yield of these mutants similar to that of the wild type protein was obtained.

FIGURE 1.

Purification of rad51 mutants. A, scheme of protein purification. B, purified Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, and rad51 G393D (2 μg each) were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie Blue.

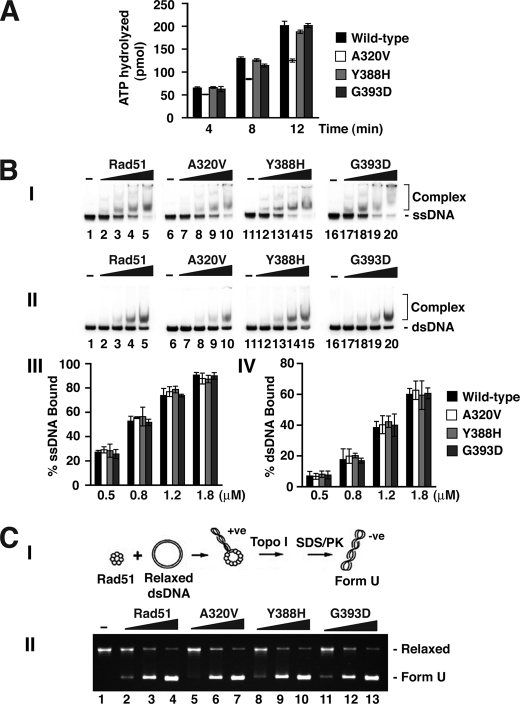

The rad51 Mutants Retain the Basic Biochemical Attributes of Rad51

Before evaluating the rad51 mutants for their physical and functional interactions with Rad52 and Srs2, we wished to first establish that they possess the biochemical attributes of the wild type protein with regards to ATP hydrolysis, DNA binding, and the ability to mediate homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange in conjunction with RPA. First, the ATPase activity was measured with ϕX174 (+) DNA as co-factor, and the results showed that all three rad51 mutant proteins possess a level of ATPase activity comparable with that of the wild type protein (Fig. 2A). By a DNA mobility shift assay conducted with radiolabeled ssDNA or dsDNA as substrate (Fig. 2B), we also verified that none of the rad51 mutants has any noticeable DNA binding deficiency. One of the key characteristic of Rad51 is the ability to form extended helical nucleoprotein filaments on DNA. The extent of nucleoprotein filament formation can be conveniently monitored by a topoisomerase I-linked assay (Fig. 2C). The resulting products are negatively supercoiled species called Form U (underwound). Fig. 2C showed that all three rad51 mutants are just as adept as the wild type protein in inducing the formation of Form U DNA.

FIGURE 2.

Biochemical properties of the rad51 mutants. A, the ATPase activity of Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D was examined. B, the ssDNA (panel I) or dsDNA (panel II) binding activity of Rad51 and rad51 mutants was examined. The amounts of these proteins used were 0.5, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.8 μm. The results from these DNA binding experiments are plotted in panels III and IV. C, DNA topology change induced by Rad51 and mutants. Panel I depicts the basis of the topoisomerase I-linked assay. In panel II, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 μm of Rad51 and the three rad51 mutants were examined for their ability to induce Form U.

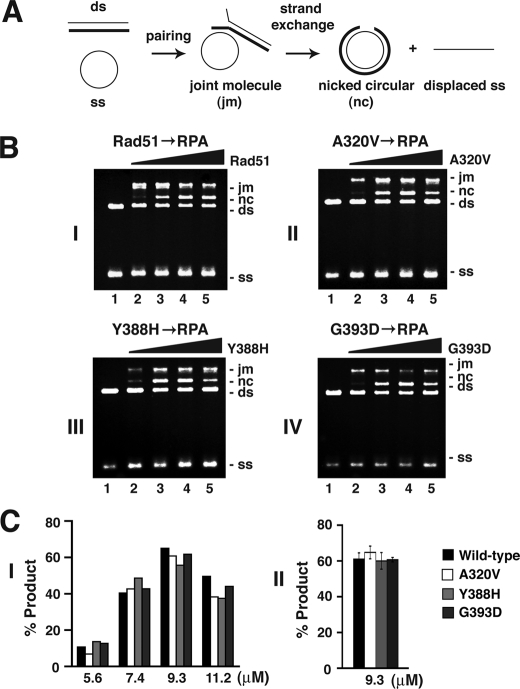

We next tested the three rad51 mutant proteins for their ability to catalyze the homologous DNA pairing and DNA strand exchange reaction. In the in vitro system used, ϕX174 circular ssDNA is first incubated with Rad51 to allow for presynaptic filament assembly, and then RPA followed by homologous linear dsDNA are added to complete the reaction. Under these prescribed conditions, RPA enhances the efficiency of the reaction, by helping remove secondary structure in the ssDNA and also sequestering the displaced ssDNA generated as a result of DNA strand exchange. As shown in Fig. 3, all three rad51 mutants generated the same level of reaction products as wild type Rad51. Thus, all three rad51 mutants are just as capable as wild type Rad51 in the catalysis of homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange. Altogether, the results from the four independent analyses as summarized above allowed us to conclude that the rad51 A320V, Y388H, and G393D mutants possess biochemical activities comparable with that of wild type Rad51.

FIGURE 3.

Homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by rad51 mutants. A, scheme of the homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange reaction. Pairing between the circular ϕX174 (+) ssDNA and linear ϕX174 dsDNA yields a joint molecule (jm), which can be further processed by strand exchange to produce a nicked circular duplex (nc). B, Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D (5.6, 7.4, 9.3, and 11.2 μm) was pre cubated with ssDNA to assemble presynaptic filaments before RPA and dsDNA addition. C, total products (joint molecule plus nicked circular duplex) catalyzed by the optimal level of Rad51 or rad51 mutant (9.3 μm) were quantified and plotted in the histogram.

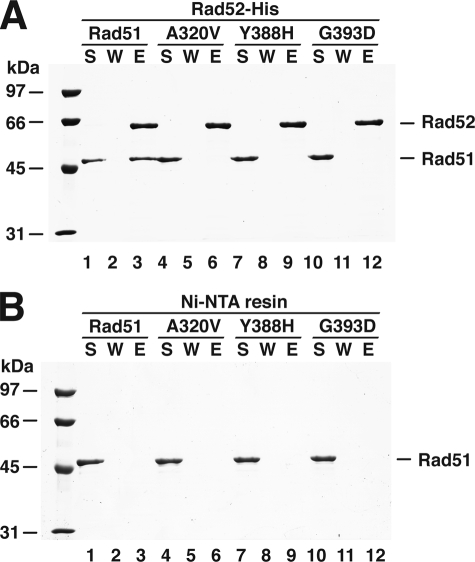

The rad51 Mutants Are Defective in Rad52 Interaction

We used affinity pulldown to test whether the rad51 mutants are defective in physical interaction with Rad52 tagged with a His6 epitope at its C terminus. For this, the purified rad51 mutants and wild type Rad51 were individually mixed with purified Rad52, and any protein complex that formed was captured on Ni-NTA resin, which recognized the His6 affinity tag on Rad52. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS and then analyzed. None of three rad51 mutants interacted with Rad52, whereas, as expected, a complex of wild type Rad51 with Rad52 was seen (Fig. 4A). Neither wild type Rad51 nor any of the rad51 mutants bound the Ni-NTA resin in the absence of Rad52 (Fig. 4B). Thus, all three rad51 mutants are defective in complex formation with Rad52. In contrast, all three rad51 mutants retain the wild type level of ability to interact with Rad54 (see later), Rdh54, and Rad59 (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Interaction of rad51 mutants with Rad52. Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D was incubated with His6-tagged Rad52. The reaction mixtures were mixed with Ni-NTA resin to capture any protein complex that had formed. Bound proteins were eluted from the resin with SDS. The supernatant (S), wash (W), and SDS eluate (E) were analyzed by 10% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining (A). Neither Rad51 nor any of the three rad51 mutants bound the Ni-NTA resin in the absence of Rad52 (B).

Reliance of Rad52 Recombination Mediator Function on Rad51 Interaction

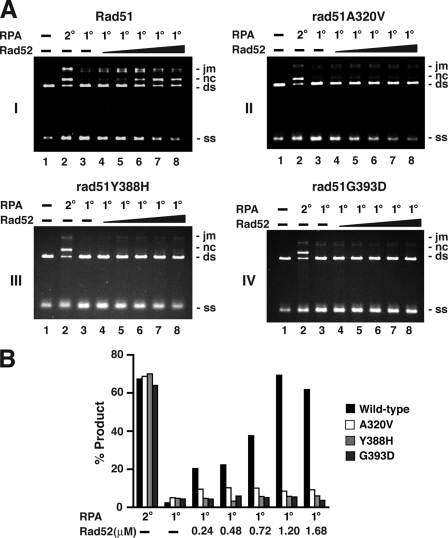

Because of the ability of RPA to compete with Rad51 for sites on ssDNA, co-addition of RPA with Rad51 to the ssDNA template strongly inhibits the homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange reaction. Importantly, the reaction efficiency can be fully restored by the inclusion of an amount of Rad52 substoichiometric to that of Rad51 (20). We used the RPA/Rad51 co-addition protocol (RPA, 1°) to test for the responsiveness of the three rad51 mutant proteins to Rad52. As expected, RPA strongly suppressed the efficiency of homologous pairing and strand exchange mediated by wild type Rad51 or any of the three mutants (Fig. 5, A, compare lanes 3 with lanes 2, and B). Importantly, although Rad52 was able to help overcome the inhibitory action of RPA with wild type Rad51 (Fig. 5, A, panel I, lanes 4–8, and B), with maximal restoration occurring at a Rad51 to Rad52 ratio of ∼10 (Fig. 5, A, panel I, and B), the inhibition posed by RPA was not at all relieved by Rad52 when any of the rad51 mutant proteins was examined (Fig. 5, A, panels II–IV, lanes 4–8, and B). These results thus provide evidence that interaction with Rad51 is critical for the efficacy of Rad52 recombination mediator activity.

FIGURE 5.

rad51 mutants are refractory to Rad52 mediator activity. A, DNA strand exchange reactions were conducted as described in Fig. 3, with RPA added after Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D was allowed to bind the ssDNA (RPA 2°) or with RPA added together with Rad51 or rad51 mutant to the ssDNA (RPA 1°). Rad52 (0.24, 0.48, 0.72, 1.2, or 1.68 μm) was added together with Rad51 and RPA, as indicated. B, the results from A were plotted. jm, joint molecule; nc, nicked circular duplex.

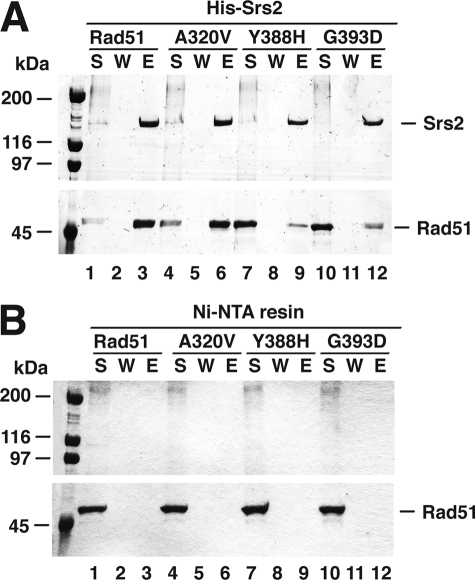

rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D Are Impaired for Srs2 Interaction

As described above and elsewhere (18), the rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, and rad51 G393D mutants are proficient in interaction with Rad54, Rdh54, and Rad59 but are specifically defective in Rad52 binding. We wondered whether these rad51 mutants retain the ability to interact with Srs2. To address this question, purified Rad51 and rad51 mutants were each mixed with His9-tagged Srs2 and subsequently with Ni-NTA affinity resin to capture protein complexes, which were eluted from the resin with SDS and analyzed. Rad51 associated with Srs2 as previously described (Fig. 6A) (16). Interestingly, whereas rad51 A320V also bound Srs2, much less rad51 Y388H or rad51 G393D was found associated with Srs2 (Fig. 6A). Specifically, whereas nearly 80% of the input Rad51 or rad51 A320V associated with Srs2, only 15% of rad51 Y388H or 17% of rad51 G393D was pulled down by Srs2 under the same conditions (Fig. 6A). As expected, neither Rad51 nor any of the rad51 mutants was retained on the Ni-NTA affinity resin without Srs2 (Fig. 6B). These affinity pulldown data thus revealed an Srs2 interaction defect in the rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D proteins and provide evidence that the rad51 A320V mutation differentially inactivates Rad52 interaction.

FIGURE 6.

Interaction of rad51 mutants with Srs2. Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D was incubated with His9-tagged Srs2, and the reaction mixtures were mixed with Ni-NTA resin to capture any protein complex that had formed. The proteins were eluted from the resin with SDS. The supernatant (S), wash (W), and SDS eluate (E) were analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining (A). Neither Rad51 nor any of the three rad51 mutants bound the Ni-NTA in the absence of Srs2 (B).

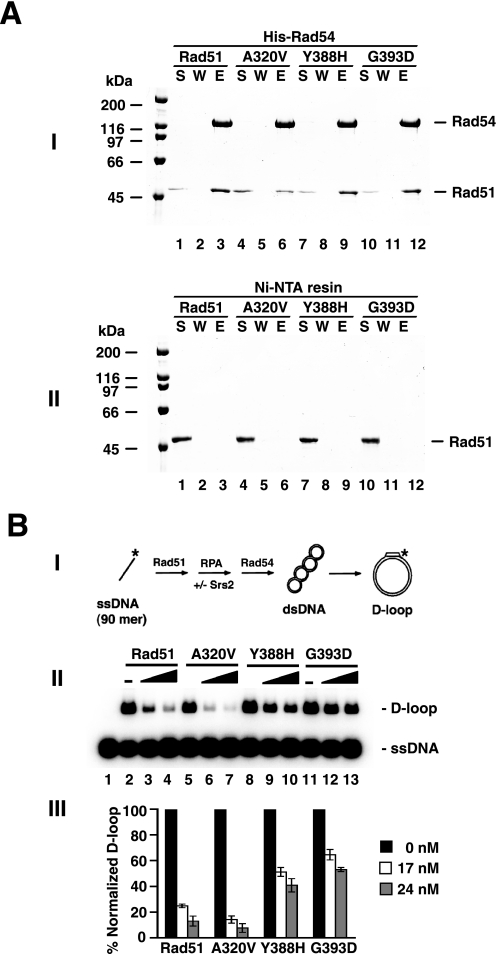

Effect of Srs2 on the D-loop Reaction Mediated by rad51 Mutants

As an anti-recombinase, Srs2 interferes with Rad51-mediated homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by disrupting the presynaptic filament (16). The availability of the rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D mutant proteins that retain the basic functional attributes of Rad51 but are defective in Srs2 interaction provides the opportunity to verify the functional significance of the Rad51-Srs2 complex in the anti-recombinase function of Srs2. Because Srs2 exerts a strong suppressive effect on the D-loop reaction mediated by the Rad51-Rad54 protein pair (16), we asked whether the D-loop reaction mediated by rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D in conjunction with Rad54 is also prone to the inhibitory action of Srs2. Consistent with their proficiency in Rad54 interaction (Fig. 7A), all three rad51 mutants gave a level of D-loop product comparable with that obtained with wild type Rad51 (Fig. 7B). However, whereas the rad51 A320V-mediated D-loop reaction was suppressed to a similar degree as in the case of wild type Rad51, much less inhibition was seen with either rad51 Y388H or rad51 G393D (Fig. 7B). These results thus revealed a dependence of Srs2 anti-recombinase function on its ability to interact with Rad51 protein.

FIGURE 7.

Resistance of the rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D mutants to Srs2. A, Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D was incubated with His6-tagged Rad54. The reaction mixtures were mixed with Ni-NTA resin to capture any protein complex that had formed. Bound proteins were eluted from the resin with SDS. The supernatant (S), wash (W), and SDS eluate (E) were analyzed by 8% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining (panel I). Neither Rad51 nor any of the three rad51 mutants bound the Ni-NTA resin in the absence of Rad54 (panel II). B, scheme of the D-loop assay is shown in panel I. Panel II shows D-loop reactions that were mediated by Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D in conjunction with Rad54 and RPA (lanes 2–13). Srs2 was added to 17 or 24 nm, where indicated. The results from panel II were quantified and plotted in panel III.

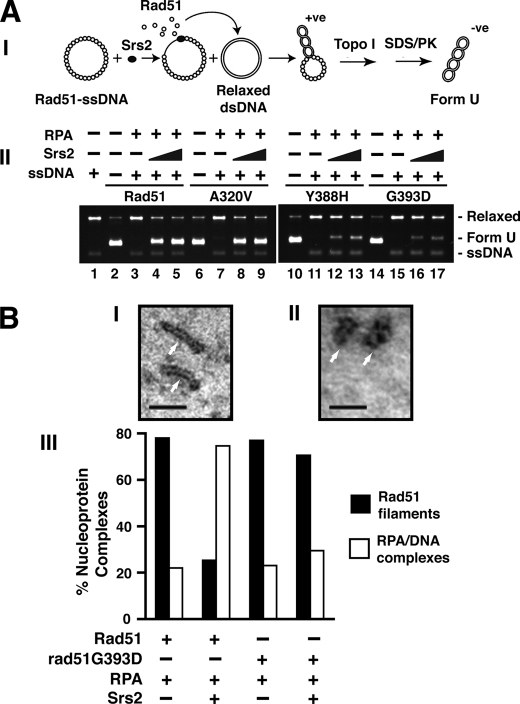

Resistance of rad51 Y388H or rad51 G393D Presynaptic Filaments to Srs2 Action

We employed a topoisomerase-linked assay to test the susceptibility of presynaptic filaments of the rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, and rad51 G393D mutants to Srs2. In this assay, Rad51 displaced from ssDNA by Srs2 is trapped on topologically relaxed dsDNA, leading to lengthening of the latter DNA species that can be monitored as a DNA linking number change upon treatment with calf thymus topoisomerase I (Fig. 8A, panel I). The underwound dsDNA species, called Form U, is visualized by ethidium bromide staining after agarose gel electrophoresis (16). We had already established that the three rad51 mutants are just as effective as the wild type protein in inducing the Form U species when allowed to bind to dsDNA (Figs. 2C and 8A, panel II, lanes 2, 6, 10, and 14). In addition, the presynaptic filaments made by the mutant proteins are stable in the absence of Srs2 (Fig. 8A, panel II, lanes 3, 7, 11, and 15).

FIGURE 8.

Resistance of the rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D presynaptic filaments to Srs2. A, the schematic of the topoisomerase I-linked assay is shown in panel I. Panel II shows the results obtained when presynaptic filaments of Rad51, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, or rad51 G393D were incubated with or without Srs2. The appropriate controls were included. B, electron microscopic analysis. Representative Rad51 nucleoprotein filaments (panel I) or RPA-ssDNA complexes (panel II) assembled on 150-mer ssDNA and imaged at 87,000× magnification. The scale bars represent 50 nm. Panel III shows the distributions of presynaptic filaments and RPA-ssDNA complexes upon incubation of Rad51 or rad51 G393D presynaptic filaments with RPA alone or with RPA and Srs2, as indicated.

The addition of Srs2 to the Rad51 presynaptic filament induced the generation of Form U (Fig. 8A, panel II, lanes 4 and 5), indicating the displacement of Rad51 from the ssDNA and trapping of the dissociated Rad51 molecules on the dsDNA. Similarly, Form U was efficiently generated when Srs2 was mixed with presynaptic filaments that harbored rad51 A320V (Fig. 8A, panel II, lanes 8 and 9). In sharp contrast, only a trace of Form U DNA was evident when presynaptic filaments of rad51 Y388H or rad51 G393D were incubated with Srs2 (Fig. 8A, panel II, lanes 12, 13, 16, and 17). These results provide clear evidence that disruption of Rad51 nucleoprotein filament by Srs2 requires the interaction of Rad51 with Srs2.

Characterization of Presynaptic Filaments by Electron Microscopy

Electron microscopy was employed to further characterize the effect of Srs2 on the Rad51 or rad51 G393D presynaptic filaments, with the prediction that the latter filaments would be more resistant to Srs2. Incubation of Rad51 or rad51 G393D with a 150-mer oligonucleotide produced abundant presynaptic filaments with the characteristic striations (Fig. 8B, panels I and III; data not shown) and few RPA-ssDNA complexes with a nondescript appearance (Fig. 8B, panels II and III). As reported previously, the addition of Srs2 to Rad51 presynaptic filaments led to their dissociation, such that the RPA-ssDNA complexes now comprised the majority of nucleoprotein species (Fig. 8B, panel III). Importantly, the presynaptic filaments of rad51 G393D were much less sensitive to the disruptive action of Srs2, because only a slight reduction in their level was observed upon the inclusion of Srs2 (Fig. 8B, panel III). Thus, these results also support the notion that the disassembly of presynaptic filament by Srs2 is dependent on the interaction between Rad51 and Srs2.

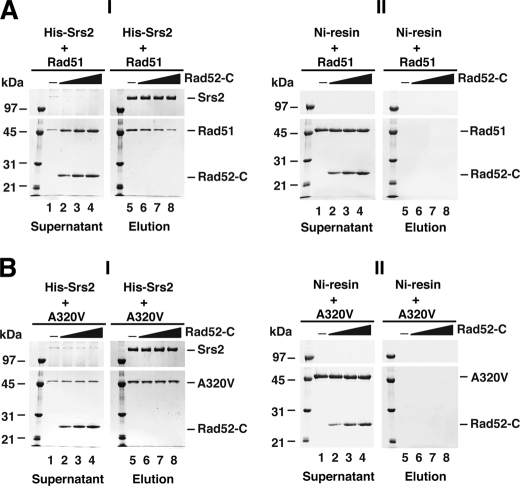

Rad52 Inhibits Rad51-Srs2 Complex Formation

Because rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D are simultaneously impaired for Rad52 and Srs2 interaction, it seems possible that the domains in Rad51 that mediate its interaction with Rad52 and Srs2 might overlap. If this were the case, then Rad52 should compete with Srs2 for Rad51 binding. To address this, His9-tagged Srs2 immobilized on Ni-NTA-agarose beads was mixed with Rad51 and an increasing concentration of a Rad52 fragment (residues 327–504, termed Rad52-C) harboring the Rad51-binding domain (26, 27). After washing the beads with buffer, bound proteins were eluted with SDS and analyzed, to quantify the amount of Srs2-Rad51 complex. As shown in Fig. 9A, less Srs2-Rad51 complex was captured on the Ni-NTA-agarose beads upon the inclusion of Rad52-C, and this effect was clearly dependent on the concentration of Rad52-C. Importantly, under the same reaction conditions, the complex made with Srs2 and rad51 A320V mutant, which we have shown earlier to be defective only in Rad52 interaction (Fig. 4), was resistant to even the highest concentration of Rad52-C tested. Thus, the results from the above pulldown experiments validate the premise that the Rad52 and Srs2 interaction domains in Rad51 overlap. They also provide further support that the change of alanine 320 in Rad51 to valine represents a separation-of-function mutation with regards to the differential impairment of Rad52 interaction.

FIGURE 9.

Rad52 interferes with Rad51-Srs2 complex assembly. Rad51 (A) or rad51 A320V (B), 5.0 μm each, was incubated with (panels I) or without (panels II) His9-tagged Srs2 (5.0 μm) in the absence or presence of 3.3, 5.0, or 6.7 μm Rad52-C. The reaction mixtures were mixed with Ni-NTA resin to capture any protein complex that had formed. After washing with buffer, the resin was treated with SDS to elute bound proteins, and the supernatant (left panels) and SDS eluate fractions (right panels) were analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining.

DISCUSSION

The inhibitory effect of RPA on Rad51 presynaptic filament assembly can be effectively overcome by Rad52 (3). By multiple criteria, including co-immunoprecipitation, yeast two-hybrid analysis, and biochemical means, yeast Rad51 and Rad52 have been shown to form a stable complex (1, 3). The Rad51 interaction domain resides within the C terminus of Rad52 (27), and previously, using variants of Rad52 that lack the C-terminal Rad51 interaction domain, we and others have provided evidence for a role of the Rad51-Rad52 complex in the delivery of Rad51 to RPA-coated ssDNA to seed the assembly of the presynaptic filament (9, 26).

To further define the importance of the Rad51-Rad52 complex in presynaptic filament assembly, we have expressed and purified three rad51 mutants that each harbor a single amino acid change, namely, rad51 A320V, rad51 Y388H, and rad51 G393D, shown previously to be impaired for Rad52 interaction by the yeast two-hybrid assay (18). We have provided herein several lines of evidence that these rad51 mutants possess normal biochemical attributes with regards to DNA binding, ATP hydrolysis, and the ability to conduct homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange. Importantly we have verified that all three rad51 mutants are indeed defective in complex formation with Rad52, even though they retain the ability to interact with other recombination factors including Rad54, Rad59, and Rdh54. Consistent with their deficiency in Rad52 interaction, none of the three rad51 mutants is responsive to the recombination mediator activity of Rad52. Thus, our analyses with these rad51 mutants along with previous studies involving the use of Rad51 interaction defective variants of Rad52 (9, 26) provide unequivocal support for the notion that physical interaction with Rad51 is indispensable for the recombination mediator attribute of Rad52.

Ablation of SRS2 leads to elevated levels of recombination including cross-over recombination, cell cycle arrest, and synthetic impairment of growth fitness in combination with other mutations (17, 28–30). Studies in the past several years have indicated that Srs2 serves the role of an anti-recombinase, acting to prevent untimely or undesirable HR events via the disruption of the Rad51 presynaptic filaments (15, 16). The ssDNA freed of Rad51 molecules via Srs2 action becomes occupied by RPA, thus making the DNA inaccessible for Rad51 reloading (16). In yeast two-hybrid and biochemical analyses, Srs2 forms a complex with Rad51, and we have mapped the Rad51 interaction domain to the C-terminal region of Srs2 (16). Unexpectedly we found that rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D, but not rad51 A320V, are impaired for Srs2 interaction. With these rad51 mutant proteins, we have presented evidence derived from biochemical and electron microscopic analyses to validate the premise that the “disruptase” activity of Srs2 relies on complex formation with the Rad51 recombinase. The interaction defective rad51 Y388H and rad51 G393D mutants are much more resistant to the anti-recombinase activity of Srs2 than is either wild type Rad51 or the interaction proficient mutant rad51 A320V. Consistent with the premise that the Rad52 and Srs2 interactions motifs overlap in Rad51, we have furnished biochemical results that Srs2 is precluded from interacting with Rad51 when an excess of Rad52 is present. However, the fact that the rad51 A320V mutation differentially inactivates the ability to interact with Rad52 suggests that the Rad52 makes an additional contact with Rad51 protein that is not shared by Srs2. Alternatively, the rad51 A320V mutation alters the conformation of Rad51 in such a fashion as to ablate Rad52 interaction without affecting Srs2 binding.

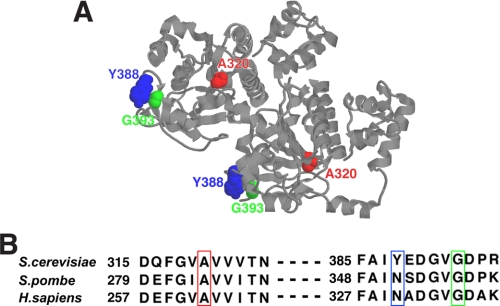

Fig. 10 maps the locations of the three rad51 mutations onto the known three-dimensional structure of the yeast Rad51 filament (Fig. 10A). We note that Tyr388 and Gly393 are located on the outer surface of the Rad51 helical polymer, whereas Ala320 is situated in the interior of the polymer. We also note that Ala320 and Gly393 are conserved among various Rad51 orthologues, including human Rad51 (Fig. 10B). It will be interesting to ask whether these residues contribute to the association of Rad51 proteins from other species with their cognate mediator proteins, such as the BRCA2 protein in human cells, and toward the association of the Rad51 orthologues with anti-recombinase proteins, such as the RECQ5 helicase in human cells (31, 32).

FIGURE 10.

Locations of the rad51 mutations in the Rad51 polymer. A, the positions of the amino acid residues Ala320, Tyr388, and Gly393 in the Rad51 filament, colored in red, blue, and green, respectively, adapted from Ref. 33. B, sequence alignment of the Rad51 orthologues from budding, fission yeast, and humans. Positions of amino acid residues explored in this study are boxed in red, blue, or green as in A.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 ES07061, RO1 GM57814, and PO1 CA92584. This work was also supported by Wellcome International Senior Research Fellowship WT076476 and GACR 301/09/317 a 203/09/H046.

- HR

- homologous recombination

- RPA

- replication protein A

- ss

- single-stranded

- ds

- double-stranded

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- DTT

- dithiothreitol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Symington L. S. (2002) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66, 630–670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung P., Klein H. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 739–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.San Filippo J., Sung P., Klein H. (2008) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 229–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jasin M. (2002) Oncogene 21, 8981–8993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D'Andrea A. D., Grompe M. (2003) Nat. Rev. Cancer 3, 23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bishop D. K., Zickler D. (2004) Cell 117, 9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianco P. R., Tracy R. B., Kowalczykowski S. C. (1998) Front. Biosci. 3, D570–D603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.New J. H., Sugiyama T., Zaitseva E., Kowalczykowski S. C. (1998) Nature 391, 407–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shinohara A., Ogawa T. (1998) Nature 391, 404–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugawara N., Wang X., Haber J. E. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 209–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolner B., van Komen S., Sung P., Peterson C. L. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 221–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lisby M., Barlow J. H., Burgess R. C., Rothstein R. (2004) Cell 118, 699–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung P., Krejci L., Van Komen S., Sehorn M. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 42729–42732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiestl R. H., Prakash S., Prakash L. (1990) Genetics 124, 817–831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veaute X., Jeusset J., Soustelle C., Kowalczykowski S. C., Le Cam E., Fabre F. (2003) Nature 423, 309–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krejci L., Van Komen S., Li Y., Villemain J., Reddy M. S., Klein H., Ellenberger T., Sung P. (2003) Nature 423, 305–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krejci L., Macris M., Li Y., Van Komen S., Villemain J., Ellenberger T., Klein H., Sung P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 23193–23199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krejci L., Damborsky J., Thomsen B., Duno M., Bendixen C. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 966–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 19.Sung P., Robberson D. L. (1995) Cell 82, 453–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seong C., Sehorn M. G., Plate I., Shi I., Song B., Chi P., Mortensen U., Sung P., Krejci L. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 12166–12174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raschle M., Van Komen S., Chi P., Ellenberger T., Sung P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 51973–51980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chi P., Kwon Y., Seong C., Epshtein A., Lam I., Sung P., Klein H. L. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26268–26279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petukhova G., Van Komen S., Vergano S., Klein H., Sung P. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 29453–29462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Komen S., Petukhova G., Sigurdsson S., Stratton S., Sung P. (2000) Mol. Cell 6, 563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petukhova G., Stratton S., Sung P. (1998) Nature 393, 91–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krejci L., Song B., Bussen W., Rothstein R., Mortensen U. H., Sung P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40132–40141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milne G. T., Weaver D. T. (1993) Genes Dev. 7, 1755–1765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aguilera A., Klein H. L. (1988) Genetics 119, 779–790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schild D. (1995) Genetics 140, 115–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gangloff S., Soustelle C., Fabre F. (2000) Nat. Genet. 25, 192–194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang H., Li Q., Fan J., Holloman W. K., Pavletich N. P. (2005) Nature 433, 653–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.San Filippo J., Chi P., Sehorn M. G., Etchin J., Krejci L., Sung P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11649–11657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Conway A. B., Lynch T. W., Zhang Y., Fortin G. S., Fung C. W., Symington L. S., Rice P. A. (2004) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 791–796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]