Abstract

Disappearance of hepatitis B surface antigens (HBsAg) in chronic hepatitis B usually indicates clearance of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. However, false HBsAg negativity with mutations in pre-S2 and 'a' determinant has been reported. It is also known that YMDD mutations decrease the production of HBV and escape detection of serum HBsAg. Here, we report overlapping gene mutations in a patient with HBsAg loss during the lamivudine therapy. After 36 months of lamivudine therapy in a 44-yr-old Korean chronic hepatitis B patient, serum HBsAg turned negative while HBV DNA remained positive by a DNA probe method. Nucleotide sequence of serum HBV DNA was compared with the HBV genotype C subtype adr registered in NCBI AF 286594. Deletion of nucleotides 23 to 55 (amino acids 12 to 22) was identified in the pre-S2 region. Sequencing of the 'a' determinant revealed amino acid substitutions as I126S, T131N, M133T, and S136Y. Methionine of rtM204 in the P gene was substituted for isoleucine indicating YIDD mutation (rtM204I). We identified a HBV mutant composed of pre-S2 deletions and 'a' determinant substitutions with YMDD mutation. Our result suggests that false HBsAg negativity can be induced by combination of overlapping gene mutations during the lamivudine therapy.

Keywords: Hepatitis B, Chronic; Hepatitis B Surface Antigens; Hepatitis B virus; Lamivudine; Mutation

INTRODUCTION

The major envelope protein of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) which consists of 226 amino acids is coded by the S gene (1). The common antigenic determinant epitopes of all subtypes of HBsAg are found in 'a' determinant which is between amino acids 124 to 147 (2). This important region is considered to be within a larger antigenic area called the major hydrophilic region (MHR), and targeted antibodies against these epitopes are used in standard assays for HBsAg to diagnose hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (3). However, we encounter some HBsAg negative chronic hepatitis B (CHB) cases with a detectable level of HBV DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in a clinical setting. This is defined as occult HBV infection (4), and has been reported in 9.4% of CHB patients (5). Usually individuals with occult HBV infection have low viremia (6). Progressive decrease in HBV load as well as replication and various relevant mutations have been implicated in such HBsAg negativity (7).

Occult HBV infection has also been documented after vaccination or hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) therapy by previous studies (8-13). Although the underlying mechanisms are fully unknown yet, nucleotide substitution or deletion of viral epitopes leading to escape from HBsAg detection has been suggested (14). As an example, some variants of 'a' determinant were isolated from a vaccinated person showing an altered antigenicity of HBsAg (8, 15). As a whole, this kind of variant HBsAg evading the known protective anti-HBs response supports the suggestion that such mutation arise as a result of immune pressure (9). Besides, it is also known that polymerase with YMDD mutation results in impaired replication efficiency of virus which may also decrease the production of HBV and escape detection (16, 17). However, no single report has been published on variant HBsAg inducing seronegativity by YMDD mutation during lamivudine therapy.

Here, we report a variant of the overlapping gene mutations isolated from a CHB patient whose serum turned into negative for HBsAg but positive for HBV DNA during a long term lamivudine therapy. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on occult HBV infection with YMDD mutation during the lamivudine therapy.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Patient

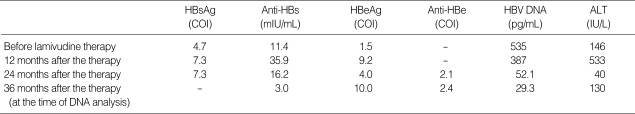

A diagnosis of chronic hepatitis B was made clinically in a 44-yr-old Korean man. It was based on the persistent elevation of serum aminotransferase levels and a positive serology for HBsAg, HBeAg, and HBV-DNA, as detected by a DNA probe method (Table 1). After 36 months of lamivudine therapy, HBsAg became negative while HBeAg and HBV-DNA remained positive. Qualitative serological tests for HBsAg were performed by using standard, commercially available, microparticle enzyme immunoassays (AxSym, Abbott Laboratories). The serum concentration of HBV DNA was 29.3 pg/mL by using a HBV hybrid capture assay II (Digene Corp, Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.).

Table 1.

Status of viral markers and serum ALT levels before and after the lamivudine therapy

COI, cut off index; -, not detected.

By using a web-based genotyping resource for viral sequences (18), a comparison was made with the published sequences of HBV genotype C subtype adr registered in GenBank (NCBI) AF 286594. The case was finally assigned as genotype C and subtype adr after deducing from the amino acid substitutions at positions 122, 127, and 160.

Methods

The nucleotide sequence of Pre-S/S region of HBV isolated from the serum of this patient was determined. In addition, the impact of any mutation within the 'a' determinant on the antigenicity of the S protein was evaluated. We also evaluated the presence of YMDD mutant in this patient.

HBV DNA was extracted from 200 µL of serum using a QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen Inc, Vanencia, CA, U.S.A.). The HBV S coding region was amplified using the following primers; HBS-1S (5'- CTT CAT TTT GTG GGT CAC CA-3', position 2803~2822) and HBS-1AS (5'- GCT TCC AAT TAC ATA TCC CAT GA -3', position 875~897). For direct sequencing, HBS-1S, HBS-1AS, HBS-2S (5'-GGA ACT CCA CCA CAT TCC AC-3', position 3212~3215. 1~16) and HBS-3S (5'-TGC CTC ATC TTC TTG TTG GTT-3', position 422~442) were used. PCR was performed for 30 cycles of denaturation at 94℃ for 30 sec and annealing at 55℃ for 30 sec, which was followed by a final primer extension at 72℃ for 1 min. Ten µL of amplified product was examined by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR products were stained with ethidium bromide after gel electrophoresis.

PCR amplified HBV DNA was purified by using a QIAgen PCR purification kit (Qiagen Inc, Vanencia, CA, U.S.A.). Purified DNA was treated with an ABI Prism BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit (Applied Biosystems, CA, U.S.A.). Sequences were determined using an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) by a bidirectional sequencing method. The nucleotide sequences were compared with the sequence of the HBV genotype C subtype adr registered in NCBI nucleotide LOCUS AF286594. Mutations were confirmed by bi-directional sequencing.

The P gene region of HBV was analysed in order to identify the YMDD mutant using a direct sequencing method. A separate set of primers or probes were not used because the whole sequence of pre-S, pre-S2, and S-gene overlapped with that of P gene.

RESULTS

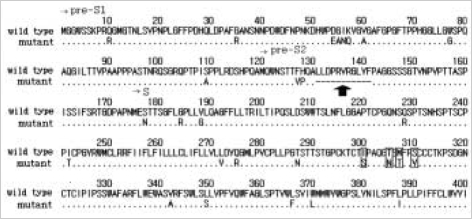

Identification of a pre-S2 deletion mutant

Comparing the S gene nucleotide and amino acid sequences of HBV with the published sequence of HBV genotype C subtype adr registered in NCBI AF 286594, the pre-S2 amplification products showed deletion from nucleotide 23 to 55 (Fig. 1). This finding was consistent with the deletion of amino acids 12 to 22 in the pre-S2 region (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Alignment of the sequence with HBV subtype adr in the pre-S2 region. Comparisons of nucleotide sequences in the S region between mutant HBV and wild type HBV (NCBI nucleotide LOCUS AF286594) reveal the deletion of nucleotide 23 to 55 in pre-S2 gene.

Fig. 2.

Translation of the pre-S2 region open reading frame aligned with the wild type. The heterogeneous amplication products reveal the presence of pre-S2 deletions. An arrow indicates pre-S2 deletions which is consistent with deletion of amino acids 12 to 22 in the pre-S2 region. Small boxes indicate the locations of amino acid substitutions within the 'a' determinant.

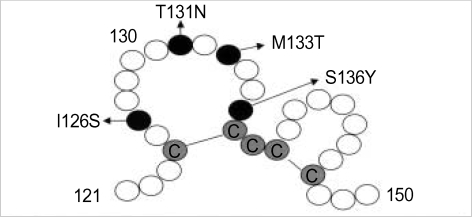

Mutations on the 'a' determinant

PCR amplification and sequencing analyses revealed point mutations resulting in amino acid substitutions at the group 'a' determinant (Fig. 3). Nucleotide substitutions included changes of T→G at codon 126, C→A at codon 131, T→C at codon 133, and C→A at codon 136. These changes were consistent with amino acid substitutions at position I126S, T131N, M133T, and S136Y.

Fig. 3.

Amino acid substitution within the 'a' loop structure of HBsAg protein. Sequencing revealed substitutions at position I126S, T131N, M133T, and S136Y in the 'a' determinant of the S gene. Black circles represent residues with mutations while gray circles represent cysteines. White circles represent other residues.

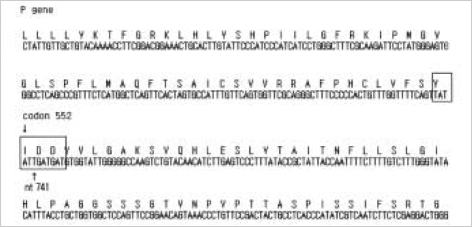

YIDD mutant

A mutation in the YMDD (tyrosine, methionine, aspartate, aspartate) motif of the viral polymerase (reverse transcriptase [rt]) was noticed as methionine 204 to isoleucine (rtM204I) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the polymerase gene. Methionine on rtM204 is substituted by isoleucine indicating YIDD mutation (rtM204I).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report an overlapping gene mutation in a CHB patient with non-detectable HBsAg despite the persistent hepatitis B viremia during a long term lamivudine therapy. Since a loss of HBsAg usually means the end of viral hepatitis, we should be aware of such occult HBV infections which might lead to confusion during the antiviral therapy.

Although the molecular mechanisms of these occult HBV infections are unresolved yet, it appears that the nondetectability of HBsAg in serum arises from several mechanisms caused by alterations in the structural, functional, and regulatory regions of HBV genome resulting in HBsAg in serum below the sensitivity of standard assays (5). Previous reports on HBsAg negative individuals with HBV persistence have suggested that genetic mutations in the S gene allows HBV to escape detection by standard HBsAg assays (14, 15, 19-24). A deletion in the pre-S region or disruption of the S promoter leads to the reduced synthesis of small surface antigen and results in the accumulation of large surface proteins in greatly dilated smooth vesicles or in the endoplasmic reticulum (25). Large surface protein usually assembles into long, branching, filamentous particles that become trapped in the endoplasmic reticulum and cannot be secreted in the absence of small surface protein (26-28). Moreover, the accumulation of large surface antigens in the cytoplasm may induce endoplasmic reticulum stress, which may alter the physiology or cell biology of the hepatocytes (28). This phenomenon is related with the control of viral replication and the evasion of immune surveillance which account for the occasional life-long persistence of HBV infection and the discrepancy between HBV DNA and HBsAg in serum (28). In addition, substitutions within the 'a' loop can create a putative glycosylation site in mutant HBVs which makes the antigenicity of HBsAg undetectable (20). Taken together, these mutations in S promoter gene and 'a' determinant might have destroyed the antigenicity of HBsAg in our patient because these amino acids are essential for the display of antigenicity (3).

Recently, Chaudhuri et al. reported that two major changes, deletion in the surface promoter region and YMDD mutations in the polymerase gene, are the most common observations in occult HBV infection (5). They found 3 cases of YMDD mutations among their 9 occult HBV infections, but all of these 3 cases were not under antiviral therapy. Therefore, our study is still the first report on a HBV variant with the combination of pre-S2 deletions, 'a' determinant substitutions, and YMDD mutation during the lamivudine therapy. This combination is important because polymerase with YMDD mutation results in impaired replication efficacy of virus, and this further leads to decreased HBV production and escape detection (16, 17). When this YMDD mutation happens with S gene promoter mutations like our case, this combination may decrease the circulating HBsAg level synergistically, making the detection of serum HBsAg impossible (5).

The limitation of our study is that we could not compare the DNA sequence variations with those before the lamivudine therapy because there was no preserved serum before the therapy. Therefore, we could not confirm whether this YMDD mutant existed even before the lamivudine therapy like previous report (29) or emerged during the lamivudine therapy. Furthermore, we could not confirm whether this YMDD mutation occurred before other mutations or not. In other words, it is difficult to decide whether pre-S2 deletions and 'a' determinant substitutions are a consequence of immune pressure created by the lamivudine therapy or just a coincidence with the emergence of YMDD mutation during the antiviral therapy. Further investigations with serial samples before and during lamivudine therapy are warranted.

In summary, a possible explanation regarding HBsAg loss during a long term lamivudine therapy in our patient is the mutations in the structural proteins consisting of pre-S2 deletions and 'a' determinant substitutions altering the antigenic properties synergistically with the YMDD mutation. The emergence of these overlapping gene mutations during the antiviral therapy should be considered significant since this false negativity might lead to confusions during the treatment. More cases of occult HBV infection during the antiviral therapy are needed for confirmation. Not only the clinical analysis concerning HBVs which escape detection by standard HBsAg assays despite the persistence of HBV DNA, but also the biological analysis should be applied in the future, so that the pathogenesis of seronegative HBV infection during the antiviral therapy can fully be understood.

References

- 1.Michael ML, Tillers P. Structure and expression of the hepatitis B virus genome. Hepatology. 1987;7:61–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840070711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carman WF, Zanetti AR, Karayiannis P, Waters J, Manzillo G, Tanzi E, Zuckerman AJ, Thomas HC. Vaccine induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus. Lancet. 1990;336:325–329. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91874-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milich DR, Chen M, Schodel F, Peterson DL, Jones JE, Hughes JL. Role of B cells in antigen presentation of the hepatitis B core. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14648–14653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conjeevaram HS, Lok AS. Occult hepatitis B virus infection: a hidden menace? Hepatology. 2001;34:204–206. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhuri V, Tayal R, Nayak B, Acharya SK, Panda SK. Occult hepatitis B virus infection in chronic liver disease: full-length genome and analysis of mutant surface promoter. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1356–1371. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Inigo E, Mariscal L, Bartolome J, Castillo I, Navacerrada C, Ortiz-Movilla N, Pardo M, Carreno V. Distribution of hepatitis B virus in the liver of chronic hepatitis C patients with occult hepatitis B virus infection. J Med Virol. 2003;70:571–580. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunther S, Fischer L, Pult I, Sterneck M, Will H. Naturally occurring variants of hepatitis B virus. Adv Virus Res. 1999;52:25–137. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60298-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee KM, Kim YS, Ko YY, Yoo BM, Lee KJ, Kim JH, Hahm KB, Cho SW. Emergence of vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus with multiple surface gene mutations in a Korean child. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:359–362. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.3.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waters JA, Kennedy M, Voet P, Hauser P, Petre J, Carman W, Thomas HC. Loss of common 'a' determinant of hepatitis B surface antigen by a vaccine-induced escape mutant. J Clin Invest. 1992;90:2543–2547. doi: 10.1172/JCI116148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison TJ, Hopes EA, Oon CJ, Zanetti AR, Zuckerman AJ. Independent emergence of a vaccine-induced escape mutant of hepatitis B virus. J Hepatol. 1991;13:S105–S107. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90037-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karthigesu VD, Allison LM, Fortuin M, Mendy M, Whittle HC, Howard CR. A novel hepatitis B virus variant in the sera of immunized children. J Gen Virol. 1994;75(Pt2):443–448. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMahon G, Ehrlich PH, Moustafa ZA, McCarthy LA, Dottavio D, Tolpin MD, Nadler PI, Ostberg L. Genetic alterations in the gene encoding the major HBsAg: DNA and immunological analysis of recurrent HBsAg derived from monoclonal antibody-treated liver transplant patients. Hepatology. 1992;15:757–766. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okamoto H, Yano K, Nozaki Y, Matsui A, Miyazaki H, Yamamoto K, Tsuda F, Machida A, Mishiro S. Mutations within the S gene of hepatitis B virus transmitted from mothers to babies immunized with hepatitis B immune globulin and vaccine. Pediatr Res. 1992;32:264–268. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199209000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato J, Hasegawa K, Torii N, Yamaguchi K, Hayashi N. A molecular analysis of viral persistence in surface antigen-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 1996;23:389–395. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v23.pm0008617416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chiou HL, Lee TS, Kuo J, Mau YC, Ho MS. Altered antigenecity of 'a' determinant variants of hepatitis B virus. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2639–2645. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-10-2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaillard RK, Barnard J, Lopez V, Hodges P, Bourne E, Johnson L, Allen MI, Condreay P, Miller WH, Condreay LD. Kinetic analysis of wild-type and YMDD mutant hepatitis B virus polymerases and effects of deoxyribonucleotide concentrations on polymerase activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:1005–1013. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.4.1005-1013.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doo E, Liang TJ. Molecular anatomy and pathophysiologic implications of drug resistance in hepatitis B virus infection. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1000–1008. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.22454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rozanov M, Plikat U, Chappey C, Kochergin A, Tatusova T. A web-based genotyping resource for viral sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Web Server issue):W654–W659. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongerius JM, Wester M, Cuypers HT, van Oostendorp WR, Lelie PN, van der Poel CL, van Leeuwen EF. New hepatitis B virus mutant from in a blood donor that is undetectable in several hepatitis B surface antigen screening assays. Transfusion. 1998;38:56–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38198141499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koyanagi T, Nakamuta M, Sakai H, Sugimoto R, Enjoji M, Koto K, Iwamoto H, Kumazawa T, Mukaide M, Nawata H. Analysis of HBs antigen negative variant of hepatitis B virus: unique substitutions, Glu129 to Asp and Gly145 to Ala in the surface antigen gene. Med Sci Monit. 2000;6:1165–1169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fan YF, Lu CC, Chang YC, Chang TT, Lin PW, Lei HY, Su IJ. Identification of a pre-S2 mutant in hepatocytes expressing a novel marginal pattern of surface antigen in advanced diseases of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:519–528. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2000.02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinberger KM, Bauer T, Bohm S, Jilg W. High genetic variability of the group-specific a-determinant of hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) and the corresponding fragment of the viral polymerase in chronic virus carriers lacking detectable HBsAg in serum. J Gen Virol. 2000;81(Pt5):1165–1174. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-5-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blum HE, Liang TJ, Galun E, Wands JR. Persistence of hepatitis B viral DNA after serological recovery from hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 1991;14:56–63. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840140110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fan YF, Lu CC, Chen WC, Yao WJ, Wang HC, Chang TT, Lei HY, Shiau AL, Su IJ. Prevalence and significance of hepatitis B virus (HBV) pre-S mutations in serum and liver at different replicative stages of chronic HBV infection. Hepatology. 2001;33:277–286. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.21163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang ZM, Yen TS. Dysregulated surface gene expression from disrupted hepatitis B genomes. J Virol. 1993;67:7032–7040. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7032-7040.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Persing DH, Varmus HE, Ganem D. Inhibition of secretion of hepatitis B surface antigen by related presurface polypeptide. Science. 1986;234:1388–1390. doi: 10.1126/science.3787251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Z, Yen TS. Intracellular retention of surface protein by a hepatitis B virus mutant that releases virion particles. J Virol. 1996;70:133–140. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.133-140.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu Z, Jesen G, Yen TS. Activation of hepatitis B virus S promoter by viral large surface protein via induction stress in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 1997;71:7387–7392. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7387-7392.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda M, Suzuki F, Suzuki Y, Tsubota A, Akuta N, Hosaka T, Someya T, Kobayashi M, Saitoh S, Arase Y, Satoh J, Kobayashi M, Ikeda K, Miyakawa Y, Kumada H. YMDD mutants in patients with chronic hepatitis B before treatment are not selected by lamivudine. J Med Virol. 2004;74:361–366. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]