Abstract

Introduction:

Smoking rates are higher among lesbian/gay/bisexual (LGB) than heterosexual (HT) individuals. However, there is scant information regarding smoking cessation treatments and outcomes in LGB populations. This study examined abstinence outcome in response to a high intensity smoking cessation program not specifically tailored to LGB smokers.

Methods:

A total of 54 gay/bisexual (GB) and 243 HT male smokers received 8-week open treatment with nicotine patch, bupropion, and counseling. Participants reported biologically verified abstinence at multiple time points during the study.

Results:

Demographic, smoking, and psychological characteristics at baseline were similar according to sexual orientation. During the first 2 weeks after quit day, abstinence rates were higher among GB smokers (Week 1: GB = 89%, HT = 82%; Week 2: GB = 77%, HT = 68%; ps < .05); abstinence rates converged subsequently, becoming nearly identical at the end of treatment (Week 8, GB = 59% vs. HT = 57%). In mixed effects longitudinal analysis of end-of-treatment outcome, sexual orientation (b = 1.40, SEM = 0.73, p = .056) and the Sexual Orientation × Time interaction (b = −0.146; SEM = 0.08, p = .058) approached statistical significance, reflecting the higher initial abstinence rates among GB smokers and the later convergence in abstinence rates by sexual orientation.

Discussion:

This first report comparing smoking cessation treatment response by sexual orientation found higher initial and similar end-of-treatment abstinence rates in GB and HT smokers. Further work is needed to determine whether these observations from GB smokers who displayed a willingness to attend a non-tailored program and broad similarity with their HT counterparts in many baseline characteristics will replicate in other groups of GB smokers.

Introduction

The prevalence of cigarette smoking is higher among lesbian/gay/bisexual (LGB) than heterosexual (HT) groups (Greenwood et al., 2005; Ryan, Wortley, Easton, Pederson, & Greenwood, 2001), posing significant risk for tobacco-related illness among individuals already at risk for other health problems (Greenwood et al.). Smoking cessation reduces that risk (Peto et al., 2000), but scant information exists relevant to quit smoking efforts and outcomes among LGB individuals (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2008).

A recent survey in Zurich, Switzerland, found that gay/bisexual (GB) male smokers reported greater preference for smoking cessation programs tailored to gay men over generic programs (Schwappach, 2008). Another study, conducted in London, found that a community-level intervention tailored for LGB smokers achieved smoking cessation rates that compared favorably with national monitoring data (Harding, Bensley, & Corrigan, 2004). A comparison of abstinence rates according to participants’ sexual orientation in response to smoking cessation interventions, whether generic or tailored to GB needs, has not been reported.

The aim of this study was to examine abstinence rates among GB compared with HT smokers in a smoking cessation treatment study that did not specifically recruit GB smokers or use a therapeutic approach targeted to any special group of smoker. The 8-week open treatment phase that preceded a maintenance treatment study (Covey et al., 2007) provided an opportunity to compare short-term cessation outcome by sexual orientation.

Methods

At the baseline visit, participants completed a self-administered form that included the following question: “Do you think of yourself as: (a) heterosexual or straight, (b) homosexual or gay or lesbian, or (c) bisexual?” Based on responses to this question, we categorized study participants as HT versus GB. Using advertisements without reference to participants’ sexual orientation, our study drew 1,859 respondents, of whom 1,047 met study eligibility criteria during telephone screen and 588 met enrollment criteria at the initial clinic visit (Covey et al., 2007). Of the enrolled group, 11.6% (68/588) self-reported LGB orientation, a percentage similar to the recent 10.6% estimate of the LGB population in the New York City metropolitan area (Gates, 2006), where our smoking cessation program is located. Among 305 males, 54 (19%) self-identified as GB, 243 (80%) as HT, and 8 (2.6%) did not answer. Among 283 female study participants, only a small number (n = 14) self-identified as LGB; this led us to restrict the present study to the sample of 297 males who answered the sexual orientation question.

The study outcome was abstinence status at Weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 (the end of treatment) following the target quit day, verified by expired carbon monoxide ≤8 parts per million (Jarvis, Tunstall-Pedoe, Feyerabend, Vesey, & Saloojee, 1987). Dropouts were considered nonabstainers. The main predictor was sexual orientation (GB vs. HT). Potential covariates selected for their putative influence on smoking cessation outcome were demographics, smoking history, body mass index (BMI), psychological variables, and psychiatric history (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of heterosexual and gay/bisexual male smokers

| Variable |

Heterosexual (n = 243), % | Gay/bisexual (n = 54), % | p value | |

| Race/ethnicity | White | 62.1 | 75.9 | ns |

| African American | 16.9 | 9.3 | ||

| Hispanic | 15.6 | 15.8 | ||

| Asian | 5.3 | 0.0 | ||

| Education | High school | 25.6 | 14.8 | ns |

| College | 46.7 | 51.9 | ||

| Graduate school | 27.7 | 33.3 | ||

| Occupational level | Upper white collar | 32.9 | 50.0 | .02 |

| Lower white collar | 34.6 | 35.2 | ||

| Blue collar | 32.5 | 14.8 | ||

| Past major depressive disorder | None | 83.5 | 77.8 | ns |

| Single episode | 11.5 | 14.8 | ||

| Recurrent | 4.9 | 7.4 | ||

| Past alcohol dependence | Absent | 81.9 | 81.5 | ns |

| Present | 18.1 | 18.5 | ||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Current age (years) | 42.4 (10.6) | 37.7 (9.0) | .002 | |

| Body mass index | 27.5 (5.5) | 25.7 (4.5 | .03 | |

| Motivation for quitting smoking | 9.1 (1.3) | 9.2 (1.1) | ns | |

| Confidence in ability to quit smoking | 7.9 (1.9) | 8.1 (1.6) | ns | |

| Number of past attempts to quit | 3.6 (2.8) | 3.6 (2.5) | ns | |

| Carbon monoxide at baseline (ppm) | 17.5 (6.5) | 17.9 (8.5) | ns | |

| Serum cotinine at baseline (ng/ml) | 265.9 (122.3) | 269.4 (113.7) | ns | |

| Age first smoked a cigarette | 16.0 (3.97) | 14.9 (3.1) | ns | |

| Age began smoking daily | 17.4 (4.1) | 17.6 (4.6) | ns | |

| Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence | 5.3 (2.1) | 5.5 (2.0) | ns | |

| Spielberger State Anxiety | 31.6 (9.1) | 30.8 (9.9) | ns | |

| Spielberger Trait Anxiety | 35.4 (8.8) | 35.9 (9.1) | ns | |

| Profile of Moods Scale–Total Mood Disturbance | .34 (14.5) | 1.3 (16.8) | ns | |

Note. ns = nonsignificant.

To test differences by sexual orientation, we used the chi-square test for categorical variables and the two-sample t test for continuous variables. To evaluate moderation of cessation outcome by sexual orientation during the 8-week treatment, we applied a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) for categorical repeated measures using a logit link function, fitted with PROC GLIMMIX in SAS, with weekly abstinence status (Weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, 8) modeled as a function of sexual orientation, time (weeks since target cessation day), age, occupational level, and BMI (baseline characteristics that significantly differentiated GB from HT smokers in the study).

Results

Compared with HT participants, GB smokers were younger, reported lower BMI, and included more upper level white collar workers (professional/executive), but did not differ on other demographic, smoking history, or psychological and psychiatric variables (Table 1). Assessments of adverse effects and compliance indicators (duration and dosage of study medications used and number of clinic visits) showed no difference by sexual orientation.

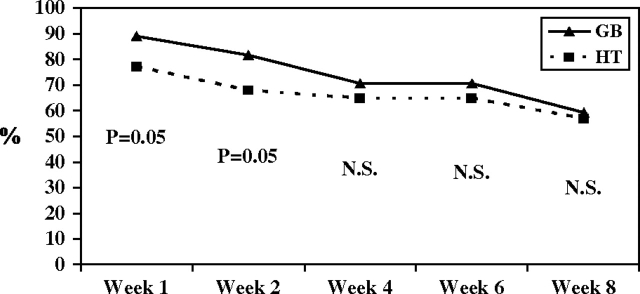

Abstinence rates at Weeks 1 and 2 were significantly higher among GB participants than among HTs (Week 1, GB = 89% and 82%; Week 2, HT = 77% and 68%; both ps = .05); as seen in Figure 1, these rates converged during the next 6 weeks, becoming nearly identical by the end of treatment (GB = 59%; HT = 57%). GLMM analysis reflected the pattern of early divergence and later convergence in cessation rates of the GB and HT subgroups. That is, higher initial abstinence among GB smokers was demonstrated by borderline statistical significance of sexual orientation (b = 1.40, SEM = 0.73, p = .056), and the later convergence of abstinence rates between GB and HT subgroups was demonstrated by the negative beta coefficient for the Sexual Orientation × Time interaction term that also approached statistical significance (b = 0.146, SEM = 0.076, p = .058).

Figure 1.

GB = gay/bisexual males (N = 54), HT = heterosexual males (N = 243). Abstinence rates (%) by sexual orientation during 8-week treatment with bupropion, nicotine patch, and counseling. p values shown for each week are from χ2 tests comparing GB versus HT.

Discussion

This first comparison of smoking quit rates according to sexual orientation in response to a non-tailored treatment program found higher abstinence rates early in treatment among GB participants and nearly identical end-of-treatment abstinence rates. This finding was unexpected in light of prior research indicating that most GB smokers would prefer a cessation program run by and attended by other gay individuals (Schwappach, 2008). It is relevant that abstinence rates at the end of 7-week treatment among gay smokers in a community-level intervention conducted in London tailored to gay smokers compared favorably with national (United Kingdom) data (Harding et al., 2004). Our results from a non-tailored program are not incompatible with both earlier studies; what our finding does suggest is that, given GB smokers who are willing to enroll in a non-tailored, high intensity program and are similar to HT participants on several baseline characteristics relevant to smoking cessation success, comparable abstinence rates by sexual orientation are achievable. Of clinical interest, GB participants showed a greater tendency to smoke again after Week 2, as illustrated in Figure 1. We have no data to explain that difference but offer the possibility that program characteristics tailored to GB issues and concerns could have been better able to sustain the higher initial abstinence rates among the GB subgroup. Further research that compares tailored with non-tailored programs among diverse groups of male and female GB smokers (the low number of female GB participants did not permit a valid analysis) and examines the role of attitudes toward generic or tailored programs is needed to clarify the influence of sexual orientation on smoking cessation outcomes.

Strengths of the study include the high rates of end-of-treatment abstinence (GB = 59%, HT = 57%), which are comparable to those observed in a large, placebo-controlled trial that demonstrated the short-term efficacy of the same treatment used in the present study, that is, combined bupropion, nicotine patch, and counseling (Jorenby, Leischow, Nides, Rennard, & Johnston, 1999). Other strengths include biological verification of abstinence reports, the use of repeated measures of abstinence, and corresponding longitudinal statistical analysis. The post-hoc nature of the data analysis limits the internal validity of our study. Selected study entry criteria, and the likely underrepresentation of GB smokers who preferred to attend a tailored program, limit external validity.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (RO1#13490) to LSC.

Declaration of Interests

Study medications were provided by GlaxoSmithKline, Inc. LSC received conference travel funds from GlaxoSmithKline, Inc. LSC and ND have received research support from Pfizer, Inc.

Supplementary Material

References

- Covey LS, Glassman AH, Jiang H, Fried J, Masmela J, LoDuca C, et al. A randomized trial of bupropion and/or nicotine gum as maintenance treatment for preventing smoking relapse. Addiction. 2007;102:1292–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates G. Same-sex couples and the gay, lesbian, bisexual population: New estimates from the American Community Survey. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, University of California, Los Angeles, UCLA School of Law; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood GL, Paul JP, Pollack LM, Brinson D, Catania JA, Chang J, et al. Tobacco use and cessation among a household-based sample of US urban men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:145–151. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.021451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding R, Bensley J, Corrigan N. Targeting smoking cessation to high prevalence communities: Outcomes from a pilot intervention for gay men. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:43–50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis MJ, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Feyerabend C, Vesey C, Saloojee Y. Comparison of tests used to distinguish smokers from nonsmokers. American Journal of Public Health. 1987;77:1435–1439. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.11.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Rennard SI, Johnston JA. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: Combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. British Medical Journal. 2000;321:323–329. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan H, Wortley PM, Easton A, Pederson L, Greenwood G. Smoking among lesbians, gays, and bisexuals. A review of the literature. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2001;21:142–149. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(01)00331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwappach DLB. Smoking behavior, intention to quit, and preferences toward cessation programs among gay men in Zurich, Switzerland. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2008;10:1783–1787. doi: 10.1080/14622200802443502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Treating tobacco use and dependence—2008 update, clinical practice guidelines. Rockville, MD: 2008. Author. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.