Abstract

In the winter-annual accessions of Arabidopsis thaliana, presence of an active allele of FRIGIDA (FRI) elevates expression of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), a repressor of flowering, and thus confers a vernalization requirement. FLC activation by FRI involves methylation of Lys 4 of histone H3 (H3K4) at FLC chromatin. Many multicellular organisms that have been examined contain two classes of H3K4 methylases, a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) Set1 class and a class related to Drosophila melanogaster Trithorax. In this work, we demonstrate that ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX-RELATED7 (ATXR7), a putative Set1 class H3K4 methylase, is required for proper FLC expression. The atxr7 mutation partially suppresses the delayed flowering of a FRI-containing line. The rapid flowering of atxr7 is associated with reduced FLC expression and is accompanied by decreased H3K4 methylation and increased H3K27 methylation at FLC. Thus, ATXR7 is required for the proper levels of these histone modifications that set the level of FLC expression to create a vernalization requirement in winter-annual accessions. Previously, it has been reported that lesions in ATX1, which encodes a Trithorax class H3K4 methylase, partially suppress the delayed flowering of winter-annual Arabidopsis. We show that the flowering phenotype of atx1 atxr7 double mutants is additive relative to those of single mutants. Therefore, both classes of H3K4 methylases appear to be required for proper regulation of FLC expression.

INTRODUCTION

Flowering is a highly regulated developmental transition from the vegetative phase to the reproductive phase in higher plants. Plants perceive both environmental and internal cues to ensure that the transition to flowering occurs during optimal times of the year to maximize reproductive success. Photoperiod and temperature are major environmental cues that influence the timing of flowering of plants adapted to temperate zones. For example, a long exposure to cold during the winter months can hasten the onset of flowering in spring in some winter-annual, biennial, and perennial species. This acquisition of competence to flower that occurs during a prolonged exposure to cold is known as vernalization (Chouard, 1960).

In Arabidopsis thaliana, the molecular basis of the vernalization requirement has been well studied (Henderson and Dean, 2004; Sung and Amasino, 2005; Dennis and Peacock, 2007). There are both summer-annual (no vernalization requirement) and winter-annual (vernalization-responsive) accessions of Arabidopsis. Studies addressing the genetic basis of natural variation for the winter-annual habit revealed that two loci, FRIGIDA (FRI) and FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), are the major determinants of natural variation for the vernalization requirement (Napp-Zinn, 1979; Koornneef et al., 1994; Lee et al., 1994a). FLC encodes a MADS box transcription factor that represses flowering, and FRI encodes a protein of unknown function (Johanson et al., 2000) that is required to elevate FLC expression to sufficient levels to repress flowering in the fall season (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999). It was recently reported that FRI interacts with Cap binding protein 20, a component of the nuclear cap binding complex, which binds to the 5′ end of eukaryotic mRNAs (Geraldo et al., 2009), raising the possibility that FRI may elevate FLC expression, at least partially, through cap binding complex activity.

In winter-annual Arabidopsis, FLC expression is repressed by vernalization, resulting in the acquisition of competence to flower in the spring (Michaels and Amasino, 1999; Sheldon et al., 1999). As a result of vernalization, histone modifications associated with gene repression, such as trimethylation of Lys 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3), accumulate at the FLC locus (Sung et al., 2006a; Finnegan and Dennis, 2007; Greb et al., 2007). This repressed state of FLC following vernalization is maintained throughout the Arabidopsis life cycle. However, the FLC locus is reset to an active state as it passes through meiosis and embryogenesis to the next generation (Sheldon et al., 2008; Choi et al., 2009).

Prior to vernalization, histone modifications associated with actively transcribed genes, such as H3K4me3 and H3K36me2/me3, are enriched at FLC (He et al., 2004; Cao et al., 2008; Oh et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2008). Elevated levels of H3K4me3 at FLC chromatin result from the presence of an active FRI locus (Kim et al., 2005; Kim and Michaels, 2006; Martin-Trillo et al., 2006). Methylation of H3K4 and H3K36 is likely to play an essential role in the transcriptional activation of FLC; the effects of FRI on FLC expression are suppressed nearly completely by mutations of certain genes involved in these histone modifications. For example, the early flowering in short days (efs) mutant exhibits reduced FLC expression as well as reduced H3K36me2/me3 levels at FLC (Zhao et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2008). The global level of H3K36me2/me3 is also decreased in the efs mutant (Zhao et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2008; Schmitz et al., 2009). EFS encodes a protein with a SET domain; SET domains catalyze histone methylation (Rea et al., 2000). The structure of the SET domain of EFS is similar to that of Set2, a yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) H3K36 methylase (Baumbusch et al., 2001).

Thus, EFS appears to be a homolog of yeast Set2 that affects H3K36 methylation in Arabidopsis. In yeast, the recruitment of Set2 and the H3K4 methylase Set1 (Briggs et al., 2001; Roguev et al., 2001) involves the RNA Polymerase II-associated factor 1 (Paf1) complex (Krogan et al., 2003a, 2003b). Mutations in the genes encoding Arabidopsis Paf1 complex components, such as EARLY FLOWERING7 (ELF7), cause a reduction of both FLC expression and H3K4 and H3K36 methylation of FLC chromatin (He et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2008). Thus, the Arabidopsis Paf1 complex is likely to activate FLC expression through both increased H3K4 and H3K36 methylation. EFS and ELF7 are also required for full expression of the FLC-related genes FLOWERING LOCUS M (FLM)/MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING1 (MAF1) and MAF2–MAF5, hereafter referred to as the FLC clade (Ratcliffe et al., 2001, 2003; Scortecci et al., 2003). This indicates that the expression of these genes also requires H3K4 and/or H3K36 methylation (Oh et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2008).

In most multicellular organisms that have been examined, H3K4 methylation is mainly catalyzed by two classes of proteins, the yeast SET1 class and a class related to Drosophila melanogaster Trithorax (Trx) (Smith et al., 2004; reviewed in Shilatifard, 2008; Avramova, 2009). In Arabidopsis, 10 proteins were identified as putative H3K4 methylases due to the similarity of the SET domains to those of Trx and/or Set1 (Baumbusch et al., 2001; Springer et al., 2003; Jacob et al., 2009). Five of these were designated ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX (ATX1-5) based on similarity of the SET domain to that of Trx and the presence of other conserved domains in Trx, such as the plant homeodomain (PHD) finger (Alvarez-Venegas and Avramova, 2001; Baumbusch et al., 2001). Thus, ATXs are thought to be the Trx class H3K4 methylases in Arabidopsis. The remaining five proteins were named ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX-RELATED (ATXR1-4 and 7). Among them, ATXR7 has a full SET domain, which is more similar to that of Set1 than that of Trx. An RNA recognition motif in Set1 is also present in ATXR7 (Avramova, 2009). Given that these Set1 features are not present in other ATXs and ATXRs, ATXR7 may be the only active ortholog of yeast Set1 in Arabidopsis (reviewed in Avramova, 2009).

Among the putative Arabidopsis H3K4 methylases, the function of ATX1 has been extensively investigated. The atx1-1 mutant exhibits homeotic conversion of floral organs as well as rapid flowering (Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2003; Pien et al., 2008). The rapid flowering is in part due to reduced FLC expression, which is accompanied by a reduction of H3K4me3 at FLC (Pien et al., 2008; Saleh et al., 2008a). Furthermore, ATX1 fails to methylate histone H3 lacking Lys 4 in vitro (Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2003). These data indicate that ATX1 functions in transcriptional activation of FLC by methylating H3K4. Moreover, an atx1-2 atx2-1 double mutant strongly suppresses the delayed-flowering phenotype of FRI (Pien et al., 2008). Because ATX2 is a close homolog of ATX1, ATX1 and ATX2 are thought to have a redundant function in the transcriptional activation of FLC (Pien et al., 2008). Interestingly, it has been reported that ATX1 and ATX2 are required for H3K4me3 and H3K4me2, respectively, at several loci other than FLC, suggesting that ATX1 and ATX2 have different biochemical functions (Saleh et al., 2008b). It has also been reported that WDR5a, an Arabidopsis homolog of a component of human H3K4 methyltransferase complexes, interacts with ATX1 and is involved in the delayed flowering caused by FRI (Jiang et al., 2009). These data support the importance of H3K4 methylation in the transcriptional activation of FLC by FRI.

In this study, we further examine the involvement of putative Arabidopsis H3K4 methylases in flowering time regulation. We find that ATXR7, in addition to ATX1/ATX2, plays a crucial role in the activation of FLC. In addition, we show that both ATXR7 and ATX1 function in the transcriptional activation of the FLC clade members, FLM, MAF4, and MAF5. Thus, we demonstrate a function for a Set1 class H3K4 methylase in the activation of specific target genes.

RESULTS

atxr7 and atx1 Mutants Flower More Rapidly Than the Wild Type in Both Long Days and Short Days

To explore the role of H3K4 methylases in flowering, the flowering behavior of all the atx and atxr mutants was examined. Multiple T-DNA insertion mutants in the Columbia (Col) background were obtained for each ATX gene (see Supplemental Table 1 online), and the mutants were evaluated for a rapid flowering phenotype in short days (noninductive photoperiods). Among the atx mutants, only atxr7 and atx1 mutants flowered more rapidly than the wild type (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). To investigate the role of the Set1 class of H3K4 methyltransferases in plants, we characterized two independent atxr7 mutants, atxr7-1 and atxr7-2, in more detail.

Both atxr7-1 and atxr7-2 flowered more rapidly than the wild type in long days (inductive photoperiods) and short days (Figure 1; see Supplemental Figure 1 online). To confirm that the rapid flowering was caused by the T-DNA insertions in the ATXR7 gene, atxr7-1 and atxr7-2 were crossed, and the flowering time of F1 plants was assessed. F1 plants were indistinguishable from atxr7-1 and atxr7-2 single mutants (see Supplemental Figure 1E online), indicating that T-DNA insertions into ATXR7 gene were responsible for the flowering phenotype. Also, as discussed below and presented in Supplemental Figure 5 online, an ATXR7 transgene rescued the flowering defect of an atxr7 mutant.

Figure 1.

ATXR7 Gene Structure and Flowering Phenotype of atxr7.

(A) ATXR7 gene structure and T-DNA insertion sites. Thick and thin lines indicate exons and introns, respectively. atxr7-1 and atxr7-2 are in the Col background.

(B) and (C) Representative plants of Col, atxr7-1, and atx1-2 atxr7-1 grown in long days ([B], 4 weeks old) or in short days ([C], 10 weeks old).

(D) and (E) Primary leaf number at flowering of Col, atxr7-1, and atx1-2 atxr7-1 grown in long days (D) or in short days (E). Closed and open bars indicate rosette and cauline leaves, respectively. The averages of the results from at least 10 plants are shown. Bars indicate sd.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

Rapid flowering of atxr7 was not as extreme as that of certain other rapid flowering mutants that affect H3K4 and/or H3K36 methylation, such as the Paf1 complex component, elf7, or the H3K36 methylase, efs (He et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005; see Supplemental Figure 1 online). In contrast with the pleiotropic phenotypes of elf7 and efs, atxr7 did not exhibit any obvious pleiotropic phenotypes except for rapid flowering (see Supplemental Figures 1 online). An atxr7 mutant in the Wassilewskija (Ws) background (atxr7-3) also flowered more rapidly in both long days and short days and did not exhibit any obvious pleiotropic phenotypes (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). Thus, we conclude that the lack of ATXR7 activity causes rapid flowering in inductive and noninductive photoperiods in multiple backgrounds, demonstrating that ATXR7 function contributes to the repression of flowering.

As described previously (Pien et al., 2008), the atx1-2 mutant was also rapid flowering both in long days and short days without exhibiting any pleiotropic phenotypes (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). atxr7 flowered slightly more rapidly than atx1-2 in short days. The atx1-2 atxr7-1 double mutant flowered more rapidly than either single mutant and did not exhibit any additional developmental defects (Figure 1).

ATXR7 and ATX1 Are Required for Expression of FLC and the FLC Clade

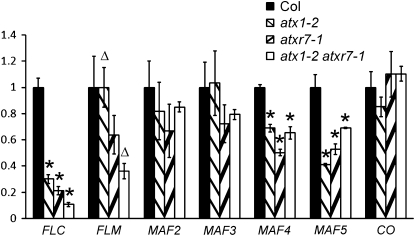

Possible targets of ATXR7 are flowering time regulators, such as FLC, the FLC clade, and CONSTANS (CO), which encodes a protein that mediates the acceleration of flowering in long days (Putterill et al., 1995; Suarez-Lopez et al., 2001). ATX1 is known to be required for the activation of FLC (Pien et al., 2008; Saleh et al., 2008a), but whether ATX1 is involved in the regulation of the FLC clade and/or CO has not been examined. Accordingly, mRNA levels of these genes were analyzed by real-time RT-PCR (Figure 2). atxr7, atx1, and atx1 atxr7 double mutants had lower levels of FLC, MAF4, and MAF5 mRNA relative to the wild type, whereas mRNA levels of MAF2 and MAF3 in the mutants exhibited no significant difference from those in the wild type. The expression of MAF4 and MAF5 in the atx1 atxr7 double mutant was similar to that of the single mutants.

Figure 2.

Expression Level of FLC and FLC-Related Family Genes in H3K4 Methylase Mutants.

Real-time PCR was performed to analyze expression levels. Because there were no significant differences between the results of atxr7-1 and atxr7-2, data from atxr7-1 are presented. The averages of the results from three different biological replicates are shown. Each experiment was normalized to ACTIN2 expression. Bars indicate the se. Asterisks above the bars indicate the significant differences in the expression levels of the genes between Col and mutants (P < 0.05). Triangles indicate the significant difference in the FLM expression level between atx1-2 and atx1-2 atxr7-1 (P = 0.017).

However, expression of FLC in the double mutants was significantly lower than that of the single mutants (P < 0.05). In addition, FLM mRNA levels in the atx1 atxr7 double mutant were lower than the wild type. Thus, ATXR7 functions in FLC activation in the atx1 mutant, and vice versa, and perhaps this redundant relationship applies to FLM activation as well. No significant change was observed for CO expression in the mutants; thus, these H3K4 methylase genes do not affect the expression of this key gene in the photoperiodic pathway of flowering. The major role of ATXR7 and ATX1 in the repression of the flowering is thus likely to be through transcriptional activation of FLC, FLM, MAF4, and MAF5. In efs-3, the expression of FLC, FLM, and MAF4 was reduced, whereas in elf7-2, the expression of FLC and all of the FLC clade was reduced (see Supplemental Figure 3 online), consistent with previous reports (He et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2008). Thus, ATX1, ATXR7, EFS, and ELF7 have varying effects on the expression of FLC and the FLC clade.

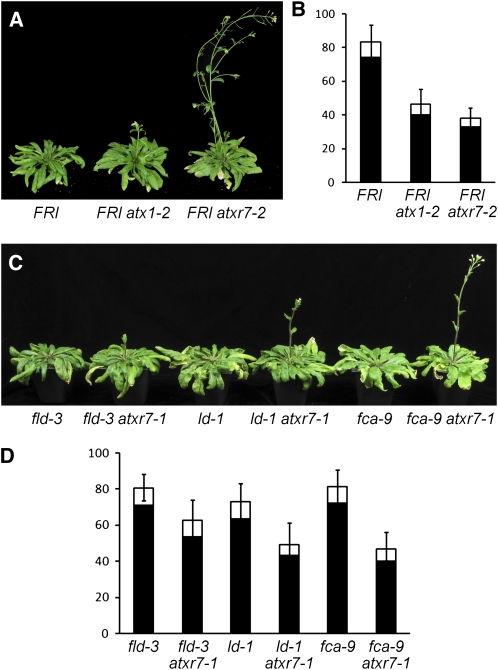

The atxr7 Mutant Suppresses the Delayed Flowering Phenotype in FRI and Autonomous Pathway Mutants

To further assess the role of H3K4 methylases in FLC activation, an active FRI locus was introgressed into all the atx and atxr mutants (see Supplemental Table 1 online) and the flowering phenotype was assessed. Among the mutants, atxr7 and atx1 exhibited the strongest suppression of the delayed flowering phenotype caused by an active FRI locus (Figures 3A and 3B; see Supplemental Figure 4 online). The effect of loss of ATX1 in FRI-mediated delayed flowering has been recently reported (Pien et al., 2008). atxr7-2 suppressed the effects of FRI slightly stronger than atx1-2. The rapid flowering phenotype of FRI atxr7 was fully rescued by an ATXR7 transgene, confirming that the phenotype was caused by the lack of ATXR7 (see Supplemental Figure 5 online).

Figure 3.

Phenotypes of atxr7 in a FRI or Autonomous Pathway Mutant Backgrounds.

(A) and (C) Representative plants of atx mutants in a FRI ([A], 7 weeks old) or autonomous pathway mutant backgrounds ([C], 9 weeks old) grown in long days.

(B) and (D) Primary leaf number at flowering of atx mutants in a FRI (B) or autonomous pathway mutant backgrounds (D) grown in long days. Closed and open bars indicate rosette and cauline leaves, respectively. The averages of the results from 9 to 20 plants are shown. Bars indicate sd. Results of t test between single autonomous pathway mutant and the double mutant with atxr7-1 are P < 0.001.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

In Arabidopsis, genes that comprise the autonomous pathway promote flowering through the suppression of FLC expression; thus, autonomous pathway mutants display elevated FLC expression and delayed flowering (Michaels and Amasino, 2001). To assess whether atxr7 can suppress the delayed flowering of autonomous pathway mutants, atxr7-1 was crossed to autonomous pathway mutants flowering locus d (fld-3), luminidependens (ld-1), and fca-9 (Lee et al., 1994b; Macknight et al., 1997; He et al., 2003). All of the double mutants flowered more rapidly than the respective single mutant (Figures 3C and 3D), and, as was the case with FRI, the suppression was partial. Thus, ATXR7 contributes to the transcriptional activation of FLC in autonomous pathway mutant backgrounds as well as in the presence of FRI.

To analyze whether ATXR7 or ATX1 functions in vernalization, the atxr7 and atx1 single mutants in a FRI background were vernalized. All of these mutants exhibited a typical vernalization response (see Supplemental Figure 4 online), indicating that neither ATXR7 nor ATX1 is essential for vernalization.

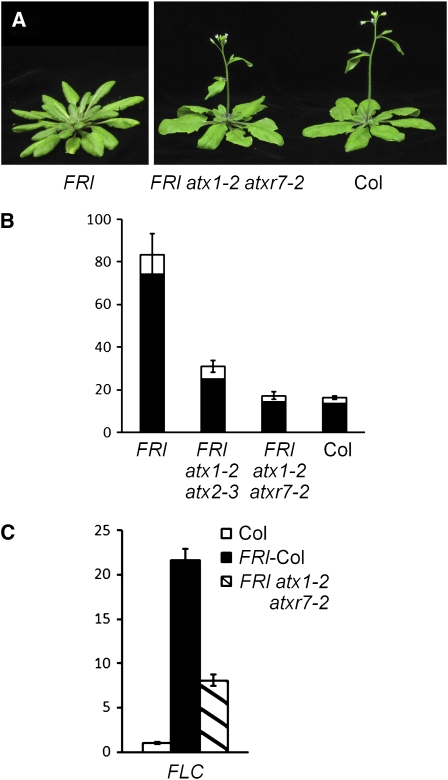

An atx1 atxr7 Double Mutant Suppresses the Delayed Flowering Caused by FRI

Because both atxr7 and atx1 single mutants partially suppressed FRI-mediated delayed flowering, we wanted to assess the phenotype of the FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 double mutant. The suppression of FRI-mediated delayed flowering caused by atx1-2 atxr7-2 was stronger than that caused by atx1-2 atx2-3 (Figure 4B; the atx1-2 atx2-1 suppression was also previously described in Pien et al., 2008). In fact, FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 flowered synchronously with Col, which lacks an active FRI locus (Figures 4A and 4B). However, in the FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 line, FLC mRNA levels were not as low as those in Col, although the FLC mRNA levels were substantially reduced relative to the FRI-Col control (Figure 4C). As shown earlier, the mRNA levels of other FLC clade members, such as FLM, were reduced in the atx1 atxr7 double mutant (Figure 2). Thus, although FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 and Col flowered synchronously, the rapid flowering of Col relative to FRI-Col is due to loss of FLC expression (Michaels and Amasino, 2001), and the rapid flowering of FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 relative to FRI-Col is likely due to a combination of FLC repression and repression of other FLC clade members.

Figure 4.

Phenotype of atx Double Mutants in a FRI Background.

(A) Representative plants of FRI-Col (6 weeks old), FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2, and Col (5 weeks old) grown in long days.

(B) Primary leaf number at flowering of atx1-2 atx2-3 and atx1-2 atxr7-2 double mutants in a FRI background grown in long days. Closed and open bars indicate rosette and cauline leaves, respectively. The averages of the results from at least nine plants are shown. Bars indicate sd.

(C) Real-time PCR was performed to analyze FLC expression in Col, FRI-Col, and the FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 mutant. The averages of the results from three different biological replicates are shown. Each experiment was normalized to ACTIN2 expression. Bars indicate the se.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

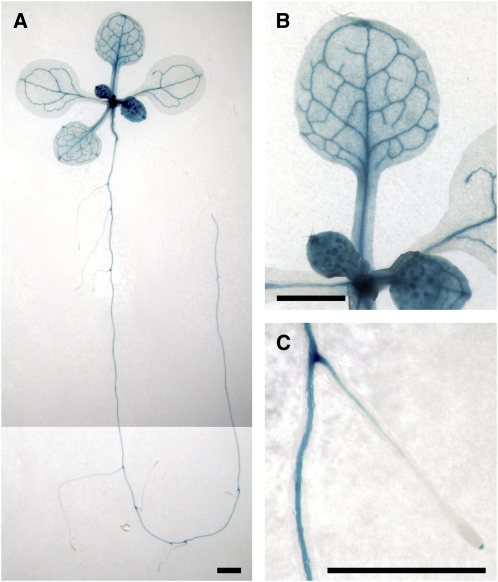

ATXR7 Directly Regulates FLC Expression

To further explore the role of ATXR7 in FLC regulation, the expression pattern of ATXR7 was analyzed by transforming an ATXR7pro:ATXR7-GUS (for β-glucuronidase) construct into a FRI atxr7-1 mutant. The ATXR7pro:ATXR7-GUS construct fully rescued the flowering phenotype of the FRI atxr7-1 mutant. In transformed lines, strong GUS activity was observed in the shoot and root apices and in the vascular tissues (Figure 5). GUS was also expressed in the mesophyll cells of rosette leaves. This expression pattern is consistent with the genome-wide expression data in the AtGenExpress database (http://www.weigelworld.org/resources/microarray/AtGenExpress/; Schmid et al., 2005) and overlaps with the FLC expression pattern (Michaels and Amasino, 2000; Sheldon et al., 2002; Pien et al., 2008), supporting a direct role of ATXR7 in FLC transcription.

Figure 5.

Expression Pattern of ATXR7pro:ATXR7-GUS in the FRI atxr7-1 Mutant.

GUS expression pattern in a representative 12-d-old ATXR7pro:ATXR7-GUS transformant. Bars = 1 mm.

(A) Entire seedling.

(B) Rosette leaf.

(C) Main and lateral roots.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

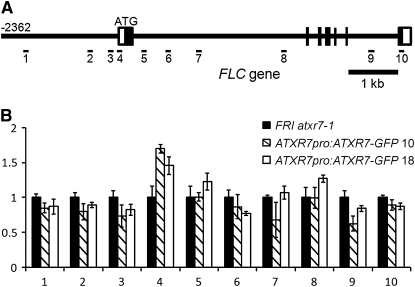

Furthermore, localization of the ATXR7 protein at FLC was analyzed by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using ATXR7pro:ATXR7-GFP (for green fluorescent protein) transformants. As with the GUS construct, the ATXR7pro:ATXR7-GFP construct fully rescued the FRI atxr7-1 mutant. Enrichment of ATXR7-GFP protein was observed around the transcription start site of FLC (Figure 6B), indicating that ATXR7 directly interacts with this region of FLC chromatin.

Figure 6.

Enrichment of ATXR7-GFP at the FLC Locus.

(A) Schematic model of primer positions at the FLC locus.

(B) Levels of the ATXR7-GFP protein at FLC. Homozygous T3 seedlings of two independent ATXR7pro:ATXR7-GFP lines (10 and 18) were used as samples. ChIP using GFP antibody and real-time PCR were performed to evaluate the occupancy of the ATXR7-GFP protein at FLC. The x axis and y axis indicate the primer number and the relative level of ATXR7-GFP enrichment, respectively. The averages of the results from three different biological replicates are shown. Each experiment was normalized to Ta3, in which mono-, di-, and trimethylation of H3K4 are not detected (Zhang et al., 2009). Bars indicate the se.

Loss of ATXR7 Alone and in Combination with Loss of ATX1 Affects Histone Modifications at FLC Chromatin

As discussed above, ATXR7 appears to be the ortholog of the yeast H3K4 methylase Set1 (Baumbusch et al., 2001). Therefore, we used ChIP to evaluate the effect of the loss of ATXR7 function on H3K4me3, H3K4me2, and H3K4me1 levels at FLC in FRI-Col, FRI atxr7-2, and FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 (Figure 7). In FRI-Col, H3K4me3 was enriched around the transcription and translation start sites as previously described (He et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2008). This enrichment of H3K4me3 was reduced in both FRI atxr7-2 and FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 (Figure 7A). The reduction was greatest in FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2, consistent with the requirement of both ATXR7 and ATX1 for FLC activation. The level of H3K4me3 reduction around the transcription start site in FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 (primer 4 in Figure 7A) correlates well with the reduction of FLC expression level in the mutant (Figure 4C). Other studies have also found that the H3K4me3 levels are well correlated with the expression level of FLC (Kim and Michaels, 2006; Martin-Trillo et al., 2006; Sung et al., 2006b; Pien et al., 2008).

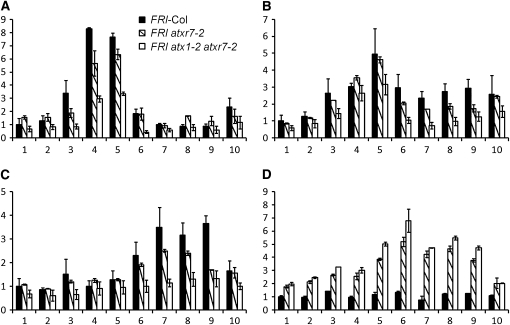

Figure 7.

H3K4 Methylation and H3K27 Trimethylation at FLC in FRI-Col, FRI atxr7-1, and FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 Mutants.

Levels of H3K4me3 (A), H3K4me2 (B), H3K4me1 (C), and H3K27me3 (D) at FLC. The x axis and y axis indicate the primer number described in Figure 6A and relative levels of modifications, respectively. The averages of the results from two different biological replicates are shown. Each experiment was normalized to total Histone H3 ChIP. Bars indicate the se.

The pattern of H3K4me2 in FRI-Col wild type was similar to that of H3K4me3, although the difference in H3K4me2 levels in various regions of FLC was not as pronounced as those for H3K4me3 (Figure 7B). Also, as observed for H3K4me3, the atxr7-2 mutation caused a modest reduction in the levels of H3K4me2, and the reduction was greater in the atx1-2 atxr7-2 double mutant.

H3K4me1 exhibits a pattern distinct from that of H3K4me2/me3; H3K4me1 was enriched at the 3′ region of FLC (Figure 7C). The levels of H3K4me1 were reduced in both FRI atxr7-2 and FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2, and the extent was again greater in FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 than in FRI atxr7-2 (Figure 7C). These results indicate that both ATXR7 and ATX1 are required for wild-type levels of mono-, di-, and trimethylation of H3K4 at FLC.

H3K27me3 is associated with the repression of FLC expression (Sung et al., 2006a; Finnegan and Dennis, 2007; Greb et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2007). We performed ChIP of FLC chromatin in FRI-Col, FRI atxr7-2, and FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 to determine whether the reduction of FLC expression in the atxr7 mutant is also associated with increased H3K27me3 (Figure 7D). In FRI-Col wild type, H3K27me3 levels were consistently low throughout the entire FLC locus, in contrast with the situation in Col (which lacks FRI) in which H3K27me3 is enriched in the body of the gene (Zhang et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2008). In FRI atxr7-2, H3K27me3 was enriched relative to FRI-Col across the entire FLC gene, particularly in the body of the gene (primers 5-9), indicating that ATXR7 activity is antagonistic to H3K27 methylation at FLC. H3K27me3 levels in FRI atx1-2 atxr7-2 were nearly equivalent to that in FRI atxr7-2, indicating that ATXR7 is the major H3K4 methylase involved in the suppression of H3K27 methylation at FLC.

An atxr7 efs Double Mutant Exhibits a Stronger Phenotype than the Single Mutants

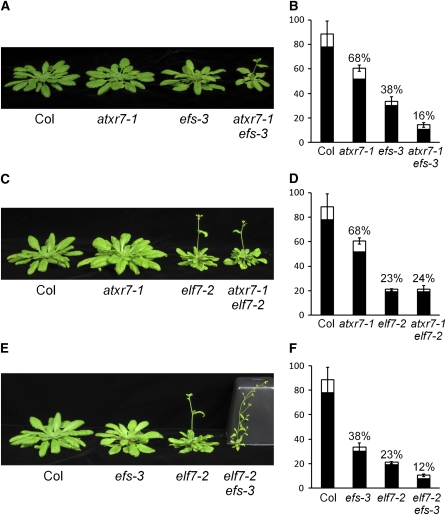

The results presented above indicate that ATXR7 is involved in the transcriptional activation of FLC and certain members of the FLC clade, most likely through H3K4 methylation. As described earlier, EFS most likely encodes a H3K36 methylase in Arabidopsis. To explore the relationship between H3K4 and H3K36 methylation, the atxr7 efs double mutant was characterized. The phenotype of the atxr7 efs double mutant transgressed that of the single mutants: the double mutant was more rapid flowering than either single mutant and had smaller size and leaves that lacked visible veins (Figures 8A and 8B).

Figure 8.

The Phenotypes of the Double Mutants among atxr7-1, elf7-2, and efs-3.

(A), (C), and (E) Representative 8-week-old plants of Col, atxr7-1, efs-3, and atxr7-1 efs-3 (A), Col, atxr7-1, elf7-2, and atxr7-1 elf7-2 (C), and Col, efs-3, elf7-2, and elf7-2 efs-3 (E) grown in short days.

(B), (D), and (F) Primary leaf number at flowering of Col, atxr7-1, efs-3, and atxr7-1 efs-3 (B), Col, atxr7-1, elf7-2, and atxr7-1 elf7-2 (D), and Col, efs-3, elf7-2, and elf7-2 efs-3 (F) grown in short days. Closed and open bars indicate rosette and cauline leaves, respectively. The averages of the results from at least nine plants are shown except for atxr7-1 elf7-2 (n = 7). Bars indicate sd. The numbers above the bars indicate the percentages of the primary leaf number at flowering compared with that of Col.

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

Loss of ATXR7 Does Not Enhance the Phenotype of a Paf1 Complex Lesion

In yeast, the Paf1 complex is required for the function of both Set1 and Set2 (Krogan et al., 2003a, 2003b). The Arabidopsis Paf1 complex plays a role in the transcriptional activation of FLC and the FLC clade through both H3K4 and H3K36 methylation (He et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2008; see Supplemental Figure 3 online). Thus, we explored whether the Arabidopsis Paf1 complex is required for the function of ATXR7. To evaluate this, we characterized the phenotype of a double mutant of ATXR7 and the Paf1 complex component ELF7. The elf7-2 single mutant exhibits a rapid flowering phenotype as well as several pleiotropic phenotypes in both long days and short days (Figure 8C; and as previously described in He et al., 2004). However, the atxr7-1 elf7-2 double mutant did not show any additional rapid flowering or pleiotropic phenotypes relative to elf7-2 (Figures 8C and 8D). This is consistent with a model in which the function of ATXR7 requires the Paf1 complex.

In contrast with atxr7 elf7, transgressive phenotypes were observed in elf7 efs double mutants: both rapid flowering and pleiotropic phenotypes were more severe when compared with the elf7 or efs single mutant (Figures 8E and 8F). The elf7 efs double mutant phenotype is reminiscent of the phenotype of vernalization independence4 (vip4) efs double mutants (Zhao et al., 2005; Xu et al., 2008); VIP4 encodes another component of Arabidopsis Paf1 complex). These results indicate that, in contrast with ATXR7, EFS has roles in Arabidopsis development that are independent of the Paf1 complex.

DISCUSSION

Both atxr7 and atx1 single mutants flowered more rapidly than wild-type plants, which is likely due to the reduction in the expression of FLC, FLM, MAF4, and MAF5 (Figures 1 and 2; see Supplemental Figure 1 online). The reduction in FLC expression was accompanied by a decrease in H3K4 methylation at the FLC locus (Figure 7). Thus, both ATXR7 and ATX1, Set1, and Trx class H3K4 methylases, respectively, repress flowering by activating the transcription of FLC, FLM, MAF4, and MAF5, and the activation most likely occurs through H3K4 methylation. A lesion in ATXR7 caused rapid flowering in FRI-Col and several autonomous pathway mutant backgrounds (Figure 3). The expression pattern of ATXR7 overlaps with that of FLC, and an ATXR7-GFP fusion protein directly binds to FLC chromatin (Figure 6), suggesting that ATXR7 directly regulates FLC transcription.

The atx1 atxr7 double mutant flowered more rapidly than the single atx1 or atxr7 mutant in both Col and FRI-Col backgrounds (Figures 1 and 4). In particular, the double mutant almost completely suppressed the delayed flowering caused by FRI, and the suppression was stronger than that caused by the atx1 atx2 double mutant (Figure 4). Despite the complete suppression of delayed flowering of a FRI-containing line by atx1 atxr7, FLC mRNA levels were higher in the FRI atx1 atxr7 double mutant than in Col. This indicates that lack of atx1 atxr7 does not fully inhibit the ability of FRI to upregulate FLC. Thus, rapid flowering of the atx1 atxr7 double mutant is due in part to lowered expression of FLC and to downregulation of other FLC clade members like FLM.

The atx1 atxr7 double mutant phenotype indicates that both Set1-type and Trx-type H3K4 methylases are required for wild-type expression levels of FLC and FLC clade members. Most plants and animals that have been examined contain both Set1-type and Trx-type H3K4 methylases, but the role of Set1-type H3K4 methylases in multicellular organisms has not been well characterized (reviewed in Shilatifard, 2008). In this study, we present a role for the Arabidopsis Set1-type H3K4 methylase in flowering time. The mechanism of transcriptional activation of FLC by ATXR7 is a potential model system to investigate not only the function of Set1-type H3K4 methylases in multicellular organisms but also the cooperation of Set1-type and Trx-type H3K4 methylases to maintain full levels of gene expression. Several differences exist between ATXR7 and ATX1. In the Ws background, the atx1-1 mutant shows severe pleiotropic phenotypes (Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2003; Pien et al., 2008) that are not present in the atxr7-3 mutant (see Supplemental Figure 2 online). In addition, ATX1 binds phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate (PI5P) through its PHD finger (Alvarez-Venegas et al., 2006). When bound to PI5P, subcellular localization of the ATX1 protein changes and the protein activity decreases. ATXR7 is not likely to bind PI5P because it lacks the PHD finger (Baumbusch et al., 2001). Given these differences, it will be interesting to further explore how ATXR7 and ATX1 cooperate to effect expression of FLC and FLC clade members.

In FRI-Col wild type, we found that H3K4me3 was enriched around the transcription and translation start sites of FLC as previously described (Figure 7; He et al., 2004). In addition, we characterized the accumulation pattern of H3K4me2 and H3K4me1 at FLC in FRI-Col wild type (Figure 7). These distribution patterns of H3K4 methylation are similar to those of transcribed genes in yeast (Santos-Rosa et al., 2002; Ng et al., 2003; Li et al., 2007). Accumulation of all states of H3K4 methylation was reduced in FRI atxr7, and the reduction was greatest in FRI atx1 atxr7 (Figure 7), indicating that both ATXR7 and ATX1 contribute to mono-, di-, and trimethylation of H3K4 at FLC. This is consistent with the requirement of both ATXR7 and ATX1 for FLC activation. Even in the atx1 atxr7 double mutant, there was more H3K4me2/me3 accumulation around the transcription and translation start sites of FLC compared with other regions of FLC. It is possible that other ATX gene(s) deposit H3K4me2/3 at FLC chromatin in the double mutant. ATX2, which has a redundant role and similar protein structure with ATX1 (Pien et al., 2008), is a good candidate.

H3K27me3 accumulated in the body of the FLC locus in atxr7 mutants (Figure 7). Thus, the action of wild-type ATXR7 leads to the suppression of H3K27 methylation. In Drosophila melanogaster, H3K4 methylation by Trx is essential to activate gene transcription by counteracting the repressive chromatin-modifying complexes that increase levels of H3K27me3 (Schuettengruber et al., 2007). Our study provides additional evidence that a similar system operates in plants; specifically, the ATXR7-mediated increase in H3K4 methylation may in turn suppress the accumulation of H3K27 methylation and result in a more active state of FLC chromatin. Genome-wide distribution of H3K4 and H3K27 methylation in Col seedlings recently revealed that H3K4me1 and H3K27me3 appear to be mutually exclusive (Zhang et al., 2007, 2009). This is consistent with our results; the FRI atxr7 and FRI atx1 atxr7 mutants exhibited reduced H3K4me1 and increased H3K27me3 levels in the body of the FLC gene compared with the FRI-Col wild type (Figure 7). Monomethylation of H3K4 by ATX1 and ATXR7 may be an important component of the suppression of H3K27me3 in the body of FLC in the FRI-Col wild type. It is interesting that in the atx1-1 mutant, which is in the Ws background and lacks FRI, the H3K27me3 level at FLC is reduced (Pien et al., 2008). In our study, loss of ATXR7 in the FRI-Col background resulted in increased levels of H3K27me3 at FLC (Figure 7). This difference in the effect of loss of ATX1 and ATXR7 might be due to the presence of FRI, which affects the levels of H3K27me3 at FLC in the parental line, other genetic background differences between Ws and Col, or result from a difference in the role of ATX1 versus ATXR7.

Although enrichment of ATXR7 protein was detected around the transcription site of FLC (Figure 6), a lesion in ATXR7 affected histone modifications throughout the entire FLC locus (Figure 7). There may be a lower level of ATXR7 occupancy across the FLC locus that is below our detection limit, or changes in histone modifications in the body of FLC may be a consequence of H3K4 methylation around the transcription site by ATXR7.

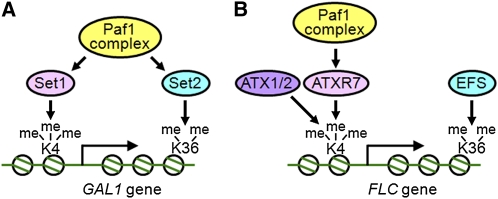

In yeast, the Paf1 complex is required for the recruitment of Set1 and Set2 (Krogan et al., 2003a, 2003b). The Arabidopsis Paf1 complex is required for the transcriptional activation of FLC and the FLC clade through H3K4 and H3K36 methylation (He et al., 2004; Oh et al., 2008; Xu et al., 2008), and our results indicate that this requirement is in part because the Arabidopsis Paf1 complex is essential for the function of ATXR7. Specifically, the atxr7 elf7 double mutant was indistinguishable from the single mutant of the Paf1 complex component ELF7 (Figure 8), indicating that ELF7 and ATXR7 are in the same pathway. The Arabidopsis Paf1 complex may function to recruit ATXR7 to target loci, such as FLC, FLM, MAF4, and MAF5, genes for which the corresponding mRNA levels were reduced in both atxr7 and elf7 mutants. Interestingly, the expression of MAF2 and MAF3 was significantly decreased in the elf7 mutant but not in atxr7, atx1, and atx1 atxr7 (Figure 2; see Supplemental Figure 3 online). Given that a lesion in another Paf1 complex component VIP4 exhibits reduced H3K4me3 levels at MAF2 and MAF3 as well as FLC and other MAF loci (Xu et al., 2008), the Paf1 complex likely activates those genes by recruiting an H3K4 methylase other than ATXR7 and ATX1.

It is interesting that, unlike the atxr7 elf7 double mutant, the atxr7 efs and elf7 efs double mutants exhibited transgressive phenotypes when compared with the single mutants (Figure 8). This indicates that at least a part of the role of EFS, the Arabidopsis homolog of the H3K36 methylase Set2, is independent of the Paf1 complex and ATXR7. It will be of interest to further investigate how the function of both H3K4 methylase and H3K36 methylase families interact to effect proper gene regulation in plants. The possible relationship among the factors involved in the histone modification and transcriptional activation of FLC is summarized in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Schematic Model of Transcriptional Activation through Histone Modifications.

Summary of the relationship among the factors involved in the transcriptional activation of the yeast GAL1 gene ([A]; from Hampsey and Reinberg, 2003) and the FLC gene (B). Circles, histone octamers; K4, Lys 4 of histone H3 (H3K4); K36, Lys 36 of histone H3 (H3K36); me, methyl groups on Lys residues.

(A) In yeast, the Paf1 complex is required for the recruitment of both Set1 and Set2, which are H3K4 and H3K36 methylases, respectively. Both trimethylation of H3K4 (H3K4me3) and dimethylation of H3K36 (H3K36me2) are involved in the transcriptional activation of certain genes including GAL1.

(B) In Arabidopsis, H3K4me3 and H3K36me2 are also essential for the transcriptional activation of FLC. Both Set1-class (ATXR7) and Trx-class (ATX1/2) H3K4 methylases are required for full H3K4 methylation and, thus, FLC activation. The Paf1 complex (including ELF7 and VIP4) is required for the function of ATXR7 and possibly ATX1/2, but not EFS (a Set2 ortholog).

[See online article for color version of this figure.]

At the time this article was accepted for publication, another article noting a role for ATXR7 in FLC activation was published (Berr et al., 2009).

METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

FRI-Col is the Col genetic background into which an active FRI locus of accession Sf-2 was introgressed (Lee and Amasino, 1995). All of the atx and atxr mutant lines analyzed in the manuscript are listed in Supplemental Table 1 online. SALK, SAIL, and WiscDsLox lines were obtained from the ABRC (Sessions et al., 2002; Alonso et al., 2003; Woody et al., 2007). GABI-Kat and FLAG lines were obtained from the European Arabidopsis Stock Centre (NASC) and Institute of Agronomic Research (Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique), respectively (Samson et al., 2002; Rosso et al., 2003).

Plants were grown in long days (16 h light/8 h dark), short days (8 h light/16 h dark), or continuous light from cool-white fluorescent tubes (PPFD ∼60 to 70 μmol m−2 s−1). Seeds were incubated in water at 4°C for 2 d and were directly sown on the soil surface (Sun-Gro; MetroMix360) or incubated on agar-solidified medium containing 0.65 g/L Peters Excel 15-5-15 fertilizer (Grace Sierra) at 4°C for 2 d and were transferred to either long days, short days, or continuous light.

Real-Time RT-PCR

Entire 10-d-old seedlings grown in continuous light were used. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 3 μg of total RNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Real-time PCR was performed on 7500 Fast Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) using DyNAmo HS SYBR Green qPCR kit (Finnzymes) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The PCR conditions were one cycle of 15 min at 95°C and 45 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s at 60°C, and 30 s at 72°C, followed by the dissociation stage as recommended by the manufacturer. Primers used to amplify the cDNAs are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online. All real-time RT-PCR data shown in the manuscript are the averages of the results from three different biological replicates and are normalized versus ACTIN2 expression.

Complementation Analysis

The ATXR7 genomic clone and its 3.1-kb native promoter were amplified by PCR with Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) according to the manufacturer's protocol (the termination codon was not included in the amplification). The MDH9 P1-derived artificial chromosome vector, obtained from the Kazusa DNA Research Institute, was used as a template for amplification (Asamizu et al., 1998). The primers used for amplification were 5′-CACCGACCGTTCGTCACAAGACTTAGCT-3′ and 5′-GTTTCGTCTTGAAAACCACGTCCT-3′. Amplified cDNA was subcloned into pENTR-D-TOPO (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Next, the cDNA was subcloned into the pMDC107 (for GFP fusion), pEG302 (for FLAG fusion), or pMDC163 (for GUS fusion) binary vector (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003; Earley et al., 2006) by site-specific recombination with Gateway LR Clonase II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendation. The plasmid was transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 (pMP90), and the bacteria were used for the transformation into the FRI atxr7-1 mutant. T1 seedlings were selected by spraying with BASTA (1/1000 dilution of Liberty herbicide; AgrEvo) several times for the pEG302 transformants or growing on plates with 25 mg/L hygromycin (MP Biomedicals) for the pMDC107 or pMDC163 transformants. The pMDC107 or pMDC163 lines that exhibited a 3:1 segregation ratio for the hygromycin resistance at the T2 generation and which fully rescued the rapid flowering phenotype of FRI atxr7-1 were used for subsequent analyses.

GUS Staining

Histochemical assays for GUS activity were performed as previously described (An et al., 1996). Briefly, plant tissues were fixed in 90% acetone on ice for 10 min, washed in 50 mM NaPO4, pH 7.0, incubated in a 0.5 mM X-gluc–containing solution with 0.5% Triton X-100, washed, and then bleached in 70% ethanol.

ChIP

Entire 10-d-old seedlings grown in continuous light were used. Preparation of chromatin samples and immunoprecipitation were performed as described previously (Johnson et al., 2002; Gendrel et al., 2005). Immunoprecipitation was performed using 10 μL of each antibody for total histone H3 (ab1791; Abcam), H3K4me3 (ab8580; Abcam), H3K4me2 (07-030; Millipore), H3K4me1 (07-436; Millipore), H3K27me3 (07-449; Millipore), and GFP (A-11122; Invitrogen). Real-time PCR was performed to detect the DNA associated with the modified or total H3 or ATXR7-GFP. PCR conditions were as described above for real-time RT-PCR. Primers (1 to 10 in Figure 6 and Ta3) are listed in Supplemental Table 2 online. The data of real-time PCR from ChIP samples shown in the manuscript are the averages of the results from three (Figure 6) or two (Figure 7) different biological replicates.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the EMBL/GenBank data libraries under accession numbers At4g00650 (FRI), At1g79730 (ELF7), At1g77300 (EFS), At5g10140 (FLC), At1g77080 (FLM), At5g65050 (MAF2), At5g65060 (MAF3), At5g65070 (MAF4), At5g65080 (MAF5), and At5g09810 (ACTIN2). Stock numbers of the T-DNA insertion lines described in this manuscript are as follows: SALK_046605 (elf7-2), SALK_141971 (flm-3), and SALK_075401 (fld-3). efs-3 (Kim et al., 2005), flc-3 (Michaels and Amasino, 1999), ld-1 (Redei, 1962), and fca-9 (Page et al., 1999) were previously described. The accession numbers of the ATX genes and information regarding T-DNA insertions in the ATX genes is described in Supplemental Table 1 online.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of the article.

Supplemental Figure 1. Flowering Phenotype of H3K4 Methylase Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 2. Flowering Phenotype of atxr7 in the Ws Background.

Supplemental Figure 3. mRNA Levels of FLC and FLC-Related Family Genes in atx1-2 atxr7-1, efs-3, and elf7-2 Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 4. Effect of Vernalization on H3K4 Methylase Mutants.

Supplemental Figure 5. Rapid Flowering Phenotype Caused by the atxr7 Lesion Is Rescued by an ATXR7 Transgene.

Supplemental Table 1. atx Mutant Lines Analyzed in the Manuscript.

Supplemental Table 2. Primers for Real-time PCR.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mark R. Doyle for much advice and Noriko Masuda, Ye Eun Kang, and Asuka Murata for assisting in our experiments. We also thank other current and previous members of the Amasino Laboratory, Donna E. Fernandez Laboratory, and Sebastian Y. Bednarek Laboratory for helpful discussions. We acknowledge Yasukazu Nakamura (Kazusa DNA Research Institute) for supplying a plasmid and the ABRC, NASC, and Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique for providing the Arabidopsis T-DNA insertion lines and a construct. This work was supported by the University of Wisconsin, the National Institutes of Health (Grant 1R01GM079525), the National Science Foundation (Grant 0446440), and the GRL Program of the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology/Korea Foundation for International Cooperation of Science and Technology.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Richard M. Amasino (amasino@biochem.wisc.edu).

Some figures in this article are displayed in color online but in black and white in the print edition.

Online version contains Web-only data.

References

- Alonso, J.M., et al. (2003). Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science 301 653–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Venegas, R., and Avramova, Z. (2001). Two Arabidopsis homologs of the animal trithorax genes: A new structural domain is a signature feature of the trithorax gene family. Gene 271 215–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Venegas, R., Pien, S., Sadder, M., Witmer, X., Grossniklaus, U., and Avramova, Z. (2003). ATX-1, an Arabidopsis homolog of trithorax, activates flower homeotic genes. Curr. Biol. 13 627–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez-Venegas, R., Sadder, M., Hlavacka, A., Baluska, F., Xia, Y., Lu, G., Firsov, A., Sarath, G., Moriyama, H., Dubrovsky, J.G., and Avramova, Z. (2006). The Arabidopsis homolog of trithorax, ATX1, binds phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate, and the two regulate a common set of target genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 6049–6054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An, Y.Q., Huang, S., McDowell, J.M., McKinney, E.C., and Meagher, R.B. (1996). Conserved expression of the Arabidopsis ACT1 and ACT 3 actin subclass in organ primordia and mature pollen. Plant Cell 8 15–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asamizu, E., Sato, S., Kaneko, T., Nakamura, Y., Kotani, H., Miyajima, N., and Tabata, S. (1998). Structural analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 5. VIII. Sequence features of the regions of 1,081,958 bp covered by seventeen physically assigned P1 and TAC clones. DNA Res. 5 379–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avramova, Z. (2009). Evolution and pleiotropy of TRITHORAX function in Arabidopsis. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 53 371–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumbusch, L.O., Thorstensen, T., Krauss, V., Fischer, A., Naumann, K., Assalkhou, R., Schulz, I., Reuter, G., and Aalen, R.B. (2001). The Arabidopsis thaliana genome contains at least 29 active genes encoding SET domain proteins that can be assigned to four evolutionarily conserved classes. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 4319–4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berr, A., Xu, L., Gao, J., Cognat, V., Steinmetz, A., Dong, A., and Shen, W.H. (2009). SET DOMAIN GROUP 25 encodes a histone methyltransferase and is involved in FLC activation and repression of flowering. Plant Physiol., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Briggs, S.D., Bryk, M., Strahl, B.D., Cheung, W.L., Davie, J.K., Dent, S.Y., Winston, F., and Allis, C.D. (2001). Histone H3 lysine 4 methylation is mediated by Set1 and required for cell growth and rDNA silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 15 3286–3295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y., Dai, Y., Cui, S., and Ma, L. (2008). Histone H2B monoubiquitination in the chromatin of FLOWERING LOCUS C regulates flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 20 2586–2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi, J., Hyun, Y., Kang, M.J., In Yun, H., Yun, J.Y., Lister, C., Dean, C., Amasino, R.M., Noh, B., Noh, Y.S., and Choi, Y. (2009). Resetting and regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS C expression during Arabidopsis reproductive development. Plant J. 57 918–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chouard, P. (1960). Vernalization and its relations to dormancy. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 11 191–238. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis, M.D., and Grossniklaus, U. (2003). A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133 462–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis, E.S., and Peacock, W.J. (2007). Epigenetic regulation of flowering. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 10 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earley, K.W., Haag, J.R., Pontes, O., Opper, K., Juehne, T., Song, K., and Pikaard, C.S. (2006). Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 45 616–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan, E.J., and Dennis, E.S. (2007). Vernalization-induced trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 27 at FLC is not maintained in mitotically quiescent cells. Curr. Biol. 17 1978–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendrel, A.V., Lippman, Z., Martienssen, R., and Colot, V. (2005). Profiling histone modification patterns in plants using genomic tiling microarrays. Nat. Methods 2 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraldo, N., Baurle, I., Kidou, S., Hu, X., and Dean, C. (2009). FRIGIDA delays flowering in Arabidopsis via a cotranscriptional mechanism involving direct interaction with the nuclear cap-binding complex. Plant Physiol. 150 1611–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greb, T., Mylne, J.S., Crevillen, P., Geraldo, N., An, H., Gendall, A.R., and Dean, C. (2007). The PHD finger protein VRN5 functions in the epigenetic silencing of Arabidopsis FLC. Curr. Biol. 17 73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampsey, M., and Reinberg, D. (2003). Tails of intrigue: Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II mediates histone methylation. Cell 113 429–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Y., Doyle, M.R., and Amasino, R.M. (2004). PAF1-complex-mediated histone methylation of FLOWERING LOCUS C chromatin is required for the vernalization-responsive, winter-annual habit in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 18 2774–2784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Y., Michaels, S.D., and Amasino, R.M. (2003). Regulation of flowering time by histone acetylation in Arabidopsis. Science 302 1751–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, I.R., and Dean, C. (2004). Control of Arabidopsis flowering: the chill before the bloom. Development 131 3829–3838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, Y., Feng, S., Leblanc, C.A., Bernatavichute, Y.V., Stroud, H., Cokus, S., Johnson, L.M., Pellegrini, M., Jacobsen, S.E., and Michaels, S.D. (2009). ATXR5 and ATXR6 are H3K27 monomethyltransferases required for chromatin structure and gene silencing. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16 763–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, D., Gu, X., and He, Y. (2009). Establishment of the winter-annual growth habit via FRIGIDA-mediated histone methylation at FLOWERING LOCUS C in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 1733–1746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson, U., West, J., Lister, C., Michaels, S., Amasino, R., and Dean, C. (2000). Molecular analysis of FRIGIDA, a major determinant of natural variation in Arabidopsis flowering time. Science 290 344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L., Cao, X., and Jacobsen, S. (2002). Interplay between two epigenetic marks. DNA methylation and histone H3 lysine 9 methylation. Curr. Biol. 12 1360–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y., He, Y., Jacob, Y., Noh, Y.S., Michaels, S., and Amasino, R. (2005). Establishment of the vernalization-responsive, winter-annual habit in Arabidopsis requires a putative histone H3 methyl transferase. Plant Cell 17 3301–3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.Y., and Michaels, S.D. (2006). SUPPRESSOR OF FRI 4 encodes a nuclear-localized protein that is required for delayed flowering in winter-annual Arabidopsis. Development 133 4699–4707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koornneef, M., Blankestijn-de Vries, H., Hanhart, C.J., Soppe, W., and Peeters, T. (1994). The phenotype of some late-flowering mutants is enhanced by a locus on chromosome 5 that is not effective in the Landsberg erecta wild-type. Plant J. 6 911–919. [Google Scholar]

- Krogan, N.J., Dover, J., Wood, A., Schneider, J., Heidt, J., Boateng, M.A., Dean, K., Ryan, O.W., Golshani, A., Johnston, M., Greenblatt, J.F., and Shilatifard, A. (2003. a). The Paf1 complex is required for histone H3 methylation by COMPASS and Dot1p: linking transcriptional elongation to histone methylation. Mol. Cell 11 721–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogan, N.J., et al. (2003. b). Methylation of histone H3 by Set2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is linked to transcriptional elongation by RNA polymerase II. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 4207–4218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I., and Amasino, R.M. (1995). Effect of vernalization, photoperiod, and light quality on the flowering phenotype of Arabidopsis plants containing the FRIGIDA gene. Plant Physiol. 108 157–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I., Aukerman, M.J., Gore, S.L., Lohman, K.N., Michaels, S.D., Weaver, L.M., John, M.C., Feldmann, K.A., and Amasino, R.M. (1994. b). Isolation of LUMINIDEPENDENS: a gene involved in the control of flowering time in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 6 75–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I., Michaels, S.D., Masshardt, A.S., and Amasino, R.M. (1994. a). The late-flowering phenotype of FRIGIDA and mutations in LUMINIDEPENDENS is suppressed in the Landsberg erecta strain of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 6 903–909. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B., Carey, M., and Workman, J.L. (2007). The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128 707–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macknight, R., Bancroft, I., Page, T., Lister, C., Schmidt, R., Love, K., Westphal, L., Murphy, G., Sherson, S., Cobbett, C., and Dean, C. (1997). FCA, a gene controlling flowering time in Arabidopsis, encodes a protein containing RNA-binding domains. Cell 89 737–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Trillo, M., Lazaro, A., Poethig, R.S., Gomez-Mena, C., Pineiro, M.A., Martinez-Zapater, J.M., and Jarillo, J.A. (2006). EARLY IN SHORT DAYS 1 (ESD1) encodes ACTIN-RELATED PROTEIN 6 (AtARP6), a putative component of chromatin remodelling complexes that positively regulates FLC accumulation in Arabidopsis. Development 133 1241–1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, S.D., and Amasino, R.M. (1999). FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 11 949–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, S.D., and Amasino, R.M. (2000). Memories of winter: Vernalization and the competence to flower. Plant Cell Environ. 23 1145–1153. [Google Scholar]

- Michaels, S.D., and Amasino, R.M. (2001). Loss of FLOWERING LOCUS C activity eliminates the late-flowering phenotype of FRIGIDA and autonomous pathway mutations but not responsiveness to vernalization. Plant Cell 13 935–941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Napp-Zinn, K. (1979). On the genetical basis of vernalization requirement in Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. In La Physiologie de la Floraison, P. Champagnat and R. Jaques, eds (Paris: Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique), pp. 217–220.

- Ng, H.H., Robert, F., Young, R.A., and Struhl, K. (2003). Targeted recruitment of Set1 histone methylase by elongating Pol II provides a localized mark and memory of recent transcriptional activity. Mol. Cell 11 709–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S., Park, S., and van Nocker, S. (2008). Genic and global functions for Paf1C in chromatin modification and gene expression in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 4 e1000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S., Zhang, H., Ludwig, P., and van Nocker, S. (2004). A mechanism related to the yeast transcriptional regulator Paf1c is required for expression of the Arabidopsis FLC/MAF MADS box gene family. Plant Cell 16 2940–2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, T., Macknight, R., Yang, C.H., and Dean, C. (1999). Genetic interactions of the Arabidopsis flowering time gene FCA, with genes regulating floral initiation. Plant J. 17 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pien, S., Fleury, D., Mylne, J.S., Crevillen, P., Inze, D., Avramova, Z., Dean, C., and Grossniklaus, U. (2008). ARABIDOPSIS TRITHORAX1 dynamically regulates FLOWERING LOCUS C activation via histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation. Plant Cell 20 580–588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putterill, J., Robson, F., Lee, K., Simon, R., and Coupland, G. (1995). The CONSTANS gene of Arabidopsis promotes flowering and encodes a protein showing similarities to zinc finger transcription factors. Cell 80 847–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, O.J., Kumimoto, R.W., Wong, B.J., and Riechmann, J.L. (2003). Analysis of the Arabidopsis MADS AFFECTING FLOWERING gene family: MAF2 prevents vernalization by short periods of cold. Plant Cell 15 1159–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, O.J., Nadzan, G.C., Reuber, T.L., and Riechmann, J.L. (2001). Regulation of flowering in Arabidopsis by an FLC homologue. Plant Physiol. 126 122–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rea, S., Eisenhaber, F., O'Carroll, D., Strahl, B.D., Sun, Z.W., Schmid, M., Opravil, S., Mechtler, K., Ponting, C.P., Allis, C.D., and Jenuwein, T. (2000). Regulation of chromatin structure by site-specific histone H3 methyltransferases. Nature 406 593–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redei, G.P. (1962). Supervital mutants in Arabidopsis. Genetics 47 443–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roguev, A., Schaft, D., Shevchenko, A., Pijnappel, W.W., Wilm, M., Aasland, R., and Stewart, A.F. (2001). The Saccharomyces cerevisiae Set1 complex includes an Ash2 homologue and methylates histone 3 lysine 4. EMBO J. 20 7137–7148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso, M.G., Li, Y., Strizhov, N., Reiss, B., Dekker, K., and Weisshaar, B. (2003). An Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA mutagenized population (GABI-Kat) for flanking sequence tag-based reverse genetics. Plant Mol. Biol. 53 247–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A., Alvarez-Venegas, R., and Avramova, Z. (2008. a). Dynamic and stable histone H3 methylation patterns at the Arabidopsis FLC and AP1 loci. Gene 423 43–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, A., Alvarez-Venegas, R., Yilmaz, M., Le, O., Hou, G., Sadder, M., Al-Abdallat, A., Xia, Y., Lu, G., Ladunga, I., and Avramova, Z. (2008. b). The highly similar Arabidopsis homologs of trithorax ATX1 and ATX2 encode proteins with divergent biochemical functions. Plant Cell 20 568–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samson, F., Brunaud, V., Balzergue, S., Dubreucq, B., Lepiniec, L., Pelletier, G., Caboche, M., and Lecharny, A. (2002). FLAGdb/FST: A database of mapped flanking insertion sites (FSTs) of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA transformants. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 94–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos-Rosa, H., Schneider, R., Bannister, A.J., Sherriff, J., Bernstein, B.E., Emre, N.C., Schreiber, S.L., Mellor, J., and Kouzarides, T. (2002). Active genes are tri-methylated at K4 of histone H3. Nature 419 407–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, M., Davison, T.S., Henz, S.R., Pape, U.J., Demar, M., Vingron, M., Scholkopf, B., Weigel, D., and Lohmann, J.U. (2005). A gene expression map of Arabidopsis thaliana development. Nat. Genet. 37 501–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz, R.J., Tamada, Y., Doyle, M.R., Zhang, X., and Amasino, R.M. (2009). Histone H2B deubiquitination is required for transcriptional activation of FLOWERING LOCUS C and for proper control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 149 1196–1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettengruber, B., Chourrout, D., Vervoort, M., Leblanc, B., and Cavalli, G. (2007). Genome regulation by polycomb and trithorax proteins. Cell 128 735–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scortecci, K., Michaels, S.D., and Amasino, R.M. (2003). Genetic interactions between FLM and other flowering-time genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 52 915–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessions, A., et al. (2002). A high-throughput Arabidopsis reverse genetics system. Plant Cell 14 2985–2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, C.C., Burn, J.E., Perez, P.P., Metzger, J., Edwards, J.A., Peacock, W.J., and Dennis, E.S. (1999). The FLF MADS box gene: A repressor of flowering in Arabidopsis regulated by vernalization and methylation. Plant Cell 11 445–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, C.C., Conn, A.B., Dennis, E.S., and Peacock, W.J. (2002). Different regulatory regions are required for the vernalization-induced repression of FLOWERING LOCUS C and for the epigenetic maintenance of repression. Plant Cell 14 2527–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, C.C., Hills, M.J., Lister, C., Dean, C., Dennis, E.S., and Peacock, W.J. (2008). Resetting of FLOWERING LOCUS C expression after epigenetic repression by vernalization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105 2214–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilatifard, A. (2008). Molecular implementation and physiological roles for histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4) methylation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20 341–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, S.T., Petruk, S., Sedkov, Y., Cho, E., Tillib, S., Canaani, E., and Mazo, A. (2004). Modulation of heat shock gene expression by the TAC1 chromatin-modifying complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 6 162–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer, N.M., Napoli, C.A., Selinger, D.A., Pandey, R., Cone, K.C., Chandler, V.L., Kaeppler, H.F., and Kaeppler, S.M. (2003). Comparative analysis of SET domain proteins in maize and Arabidopsis reveals multiple duplications preceding the divergence of monocots and dicots. Plant Physiol. 132 907–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez-Lopez, P., Wheatley, K., Robson, F., Onouchi, H., Valverde, F., and Coupland, G. (2001). CONSTANS mediates between the circadian clock and the control of flowering in Arabidopsis. Nature 410 1116–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, S., and Amasino, R.M. (2005). Remembering winter: Toward a molecular understanding of vernalization. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 56 491–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, S., He, Y., Eshoo, T.W., Tamada, Y., Johnson, L., Nakahigashi, K., Goto, K., Jacobsen, S.E., and Amasino, R.M. (2006. b). Epigenetic maintenance of the vernalized state in Arabidopsis thaliana requires LIKE HETEROCHROMATIN PROTEIN 1. Nat. Genet. 38 706–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung, S., Schmitz, R.J., and Amasino, R.M. (2006. a). A PHD finger protein involved in both the vernalization and photoperiod pathways in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 20 3244–3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woody, S.T., Austin-Phillips, S., Amasino, R.M., and Krysan, P.J. (2007). The WiscDsLox T-DNA collection: An Arabidopsis community resource generated by using an improved high-throughput T-DNA sequencing pipeline. J. Plant Res. 120 157–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., Zhao, Z., Dong, A., Soubigou-Taconnat, L., Renou, J.P., Steinmetz, A., and Shen, W.H. (2008). Di- and tri- but not monomethylation on histone H3 lysine 36 marks active transcription of genes involved in flowering time regulation and other processes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Cell. Biol. 28 1348–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Bernatavichute, Y.V., Cokus, S., Pellegrini, M., and Jacobsen, S.E. (2009). Genome-wide analysis of mono-, di- and trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Biol. 10 R62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Clarenz, O., Cokus, S., Bernatavichute, Y.V., Pellegrini, M., Goodrich, J., and Jacobsen, S.E. (2007). Whole-genome analysis of histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation in Arabidopsis. PLoS Biol. 5 e129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z., Yu, Y., Meyer, D., Wu, C., and Shen, W.H. (2005). Prevention of early flowering by expression of FLOWERING LOCUS C requires methylation of histone H3 K36. Nat. Cell Biol. 7 1256–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.