Abstract

Cytokinins play crucial roles in diverse aspects of plant growth and development. Spatiotemporal distribution of bioactive cytokinins is finely regulated by metabolic enzymes. LONELY GUY (LOG) was previously identified as a cytokinin-activating enzyme that works in the direct activation pathway in rice (Oryza sativa) shoot meristems. In this work, nine Arabidopsis thaliana LOG genes (At LOG1 to LOG9) were predicted as homologs of rice LOG. Seven At LOGs, which are localized in the cytosol and nuclei, had enzymatic activities equivalent to that of rice LOG. Conditional overexpression of At LOGs in transgenic Arabidopsis reduced the content of N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)adenine (iP) riboside 5′-phosphates and increased the levels of iP and the glucosides. Multiple mutants of At LOGs showed a lower sensitivity to iP riboside in terms of lateral root formation and altered root and shoot morphology. Analyses of At LOG promoter:β-glucuronidase fusion genes revealed differential expression of LOGs in various tissues during plant development. Ectopic overexpression showed pleiotropic phenotypes, such as promotion of cell division in embryos and leaf vascular tissues, reduced apical dominance, and a delay of leaf senescence. Our results strongly suggest that the direct activation pathway via LOGs plays a pivotal role in regulating cytokinin activity during normal growth and development in Arabidopsis.

INTRODUCTION

Cytokinins are a class of phytohormones known as key regulators of plant growth and development, including cell division, leaf senescence, apical dominance, lateral root formation, stress tolerance, and nutritional signaling (Mok, 1994; Sakakibara, 2006; Argueso et al., 2009). Major natural cytokinins in plants are N6-prenylated adenine derivatives, such as N6-(Δ2-isopentenyl)adenine (iP), trans-zeatin (tZ), cis-zeatin, and dihydrozeatin, which are known as the isoprenoid cytokinins (Mok and Mok, 2001; Sakakibara, 2006). Among them, iP and tZ are major forms in Arabidopsis thaliana. In the flowering plant biosynthetic pathway, iP nucleotide is initially produced as a cytokinin precursor by adenosine phosphate-isopentenyltransferase (IPT) using dimethylallyl diphosphate and adenosine phosphate as substrates (Kakimoto, 2001; Takei et al., 2001a; Sakamoto et al., 2006). tZ nucleotide is then formed by cytokinin hydroxylase, which hydroxylates the trans-end of the prenyl side chain of iP nucleotide (Takei et al., 2004a). To become biologically active, both nucleotides are converted to the corresponding nucleobases. Inactivation of cytokinins occurs by degradation or conjugation. Cytokinin oxidase (CKX) is responsible for cytokinin degradation (Houba-Herin et al., 1999; Morris et al., 1999; Schmülling et al., 2003; Galuszka et al., 2007). Cytokinin glycosyltransferases conjugate a glucose moiety to the 7N or 9N atom of the adenine ring or a glucose or xylose moiety to the oxygen atom of the prenyl side chain of zeatins (Martin et al., 1999a, 1999b, 2001; Mok and Mok, 2001; Hou et al., 2004). Enzymes of the purine salvage pathway convert the active nucleobase forms to inactive nucleotide forms (Schnorr et al., 1996; Mok and Mok, 2001; Allen et al., 2002; Sakakibara, 2006).

Two pathways have been proposed to be involved in producing active cytokinin species from nucleotides in plants: the two-step activation pathway and the direct activation pathway (Chen, 1997; Kurakawa et al., 2007). In the two-step pathway, cytokinin riboside 5′-monophosphates are successively converted to the corresponding nucleosides and nucleobases by nucleotidase and nucleosidase, respectively, although the responsible genes have not been identified yet. From studies on partially purified nucleosidases and nucleotidases from wheat germ, the enzymes are reported to not only react with cytokinin nucleotides or nucleosides, but also hydrolyze adenosine or AMP with higher affinities (Chen and Kristopeit, 1981a, 1981b). By contrast, the direct pathway mediates production of cytokinin nucleobase from the corresponding cytokinin riboside 5′-monophosphate. This enzyme was discovered through the analysis of rice (Oryza sativa) lonely guy (log) mutants that are deficient in the maintenance of shoot meristems (Kurakawa et al., 2007). The responsible gene, LOG, encodes a cytokinin riboside 5′-monophosphate phosphoribohydrolase that releases cytokinin nucleobase and ribose 5′-monophosphate. LOG hydrolyzes only cytokinin riboside 5′-monophosphate but not AMP, suggesting that LOG is specifically involved in cytokinin activation. It is not clear, however, whether the direct activation pathway is biologically important in plant organs or tissues other than the shoot meristem of rice and whether there is a functional differentiation between these two activating pathways.

Analyses of spatiotemporal expression patterns of Arabidopsis IPTs demonstrated tissue- and organ-specific distribution of cytokinin precursor biosynthesis (Miyawaki et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004b). IPT1 is expressed in xylem precursor cell files in root, leaf axils, ovules, and immature seeds; IPT3 is expressed in phloem tissues; IPT4 and IPT8 are expressed in immature seeds with higher expression in the chalazal endosperm; IPT5 is expressed in lateral root primordia, columella root caps, and fruit abscission zones; and IPT7 is expressed in phloem, the endodermis of the root elongation zones, trichomes on young leaves, and in pollen tubes (Miyawaki et al., 2004). However, the sites of IPT expression do not always coincide with those of active cytokinin formation. Cytokinins are mobile phytohormones and function as paracrine or long-distance signals. Xylem and phloem saps contain cytokinins mainly in the form of precursors, such as nucleosides and nucleotides (Corbesier et al., 2003; Hirose et al., 2008). Thus, a portion of cytokinin precursors could be translocated to other tissues or organs to be activated; however, the spatiotemporal distribution of the pathway responsible for active cytokinin formation remains to be clarified.

Phenotypic studies on transgenic plants overexpressing CKX were reported in Arabidopsis (Werner et al., 2003) and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Werner et al., 2001). In roots of transgenic Arabidopsis, meristem size was enlarged and lateral root formation was enhanced by overexpression of At CKX (Werner et al., 2003). By contrast, the activities of vegetative and floral shoot apical meristems and leaf primordia were diminished in the shoots of plants overexpressing At CKX, resulting in severe dwarfism (Werner et al., 2003). On the other hand, transgenic plants overexpressing IPT conferred enhanced shooting, reduced apical dominance, and delayed senescence in petunia (Petunia hybrida; Zubko et al., 2002) and showed arrest of growth and development shortly after germination in Arabidopsis (Sun et al., 2003). The overexpression of CKX increases metabolic flow toward degradation and that of IPT increases metabolic flow toward de novo cytokinin biosynthesis. Although the activation step for cytokinins must be important for regulating activity, the morphological and metabolic responses to the changes in metabolic flow resulting from the activation step have not been characterized yet.

To elucidate the detailed mechanism of the direct activation pathway, we focused on LOG-like genes in Arabidopsis. Characterization of the biochemical properties, morphological response to loss-of-function and gain-of-function gene modulations, and spatial expression patterns suggest that the direct activation pathway plays a pivotal role in regulating cytokinin activity during normal growth and development in Arabidopsis.

RESULTS

Isolation of cDNAs Encoding LOG-Like Proteins from Arabidopsis

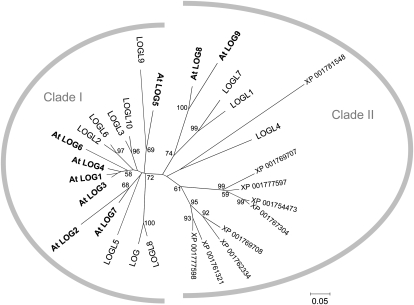

We screened the genome sequence of Arabidopsis on The Arabidopsis Information Resource (http://www.Arabidopsis.org/) in silico using the amino acid sequence of rice LOG (Kurakawa et al., 2007) as a query. Nine LOG-like genes, designated as LOG1 to LOG9 with significant similarity to rice LOG, were found (see Supplemental Table 1 online). The reading frames of the deduced At LOG proteins consisted of 143 (LOG9) to 229 (LOG6) amino acids that had 63.7% (LOG9) to 79.9% (LOG3) amino acid identity to rice LOG. The deduced amino acid sequence of At LOG9 lacked the N-terminal third of the rice LOG sequence. Analysis of phylogenetic relationships in comparison with other LOG-like proteins in rice (Rice Annotation Project Database, http://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/) and moss (Physcomitrella patens; PHYSCObase, http://www.nibb.ac.jp/evodevo/0.TopE.html) showed that the LOG-like proteins had diverged into two clades: At LOG1 to LOG7 belong to clade I, which includes rice LOG, and At LOG8 and LOG9 belong to clade II (Figure 1). Both clades include rice LOG-like proteins. All nine moss LOG-like proteins belong to clade II.

Figure 1.

Unrooted Phylogenetic Tree of LOG and Homologs in Arabidopsis, Rice, and Moss.

Full-length protein sequences from Arabidopsis (At LOGs), rice (LOG and LOGLs), and moss (XP 001754473, XP 001761321, XP 001762334, XP 001767304, XP 001769707, XP 001769708, XP 001777597, XP 001777598, and XP 001781548) were obtained from protein databases. The phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA 4.0 program (http://www.megasoftware.net) using the neighbor-joining method. The phylogenetic tree was constructed with 1000 bootstrapping replicates. The bootstrap values of 50% and above are indicated on the tree. The scale bar represents 0.05 amino acid substitutions per site.

To obtain cDNAs for the Arabidopsis LOG-like genes, total RNA was prepared from Arabidopsis seedlings, and RT-PCR was performed with specific primers for each predicted gene. cDNA fragments of LOG1 to LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 genes were amplified with expected lengths (data not shown), whereas only unexpectedly spliced cDNAs were amplified for LOG6 and LOG9, and all sequences contained predicted premature stop codons (see Supplemental Data Set 1 online). Thus, LOG6 and LOG9 were excluded from further studies.

Biochemical Characterization of Recombinant LOGs

To examine the ability of the At LOG translation products to catalyze the cytokinin activating reaction, LOG1 to LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 were expressed in Escherichia coli as His-tagged recombinant proteins. Purified recombinant proteins were used to characterize the enzymatic properties of each gene product. As is the case with rice LOG, all seven recombinant At LOGs reacted with iP riboside 5′-monophosphate (iPRMP) (Table 1) but not to iP, iP riboside (iPR), iPR 5′-diphosphate, iPR 5′-triphosphate, or AMP (data not shown).

Table 1.

Kinetic Parameters of Recombinant LOG and At LOG Proteins.

| Enzyme | Km | Vmax | kcat | kcat/Km | Sp. Ratioa | Optimum pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μM | Units mg−1 Protein | min−1 | min−1 M−1 | % | ||

| At LOG1 | 16 ± 2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 50 | 3.2 × 106 | 26 | 6.5 |

| At LOG2 | 58 ± 15 | 14 ± 2 | 328 | 5.6 × 106 | 45 | 6.5 |

| At LOG3 | 14 ± 2 | 1.5 ± 0.0 | 34 | 2.5 × 106 | 20 | 6.5 |

| At LOG4 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.2 | 103 | 1.2 × 107 | 97 | 6.5 |

| At LOG5 | 11 ± 1 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 19 | 1.6 × 106 | 13 | 5.4 |

| At LOG7 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.2 | 91 | 1.4 × 107 | 110 | 6.5 |

| At LOG8 | 17 ± 1 | 0.053 ± 0.009 | 1.3 | 7.7 × 104 | 0.6 | 7.0 |

| LOG |

12 ± 1b |

5.6 ± 1.1b |

145 |

1.2 × 107 |

100 |

6.5b |

The kinetic parameters for iPRMP were measured at the optimum pH for each enzyme. Means ± sd (n = 3).

Sp. Ratio is the specificity ratio, which is the relative kcat/Km with the value of LOG taken as 100%.

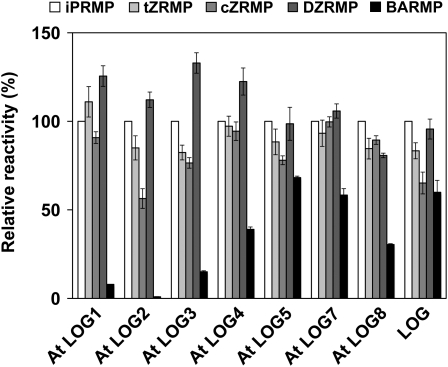

Enzymatic properties of the recombinant LOGs are summarized in Table 1. The At LOGs showed similar substrate affinities as rice LOG. However, the Km value of At LOG2 was >4 times that of rice LOG, and the kcat value was twice that of rice LOG. The kcat/Km ratio for At LOG8 was <1% of the corresponding value for rice LOG. The recombinant At LOGs had pH optima ranging from 5.4 to 7.0. Similar to rice LOG, At LOGs showed no specialized substrate specificity for isoprenoid cytokinin nucleotides but showed different reactivities toward aromatic cytokinins (Figure 2): the relative activities of At LOG1, LOG2, and LOG3 with benzyladenine riboside 5′-monophosphate were <25% of their activity with iPRMP as the substrate, whereas the activities of At LOG5, LOG7, and rice LOG were higher than 50%.

Figure 2.

Substrate Specificities of Recombinant LOG and At LOG Proteins.

Enzymes were incubated at their optimum pHs with 100 μM cytokinin nucleotides. Error bars represent the sd (n = 3). tZRMP, trans-zeatin riboside 5′-monophosphate; cZRMP, cis-zeatin riboside 5′-monophosphate; DZRMP, dihydrozeatin riboside 5′-monophosphate; BARMP, benzyladenine riboside 5′-monophosphate.

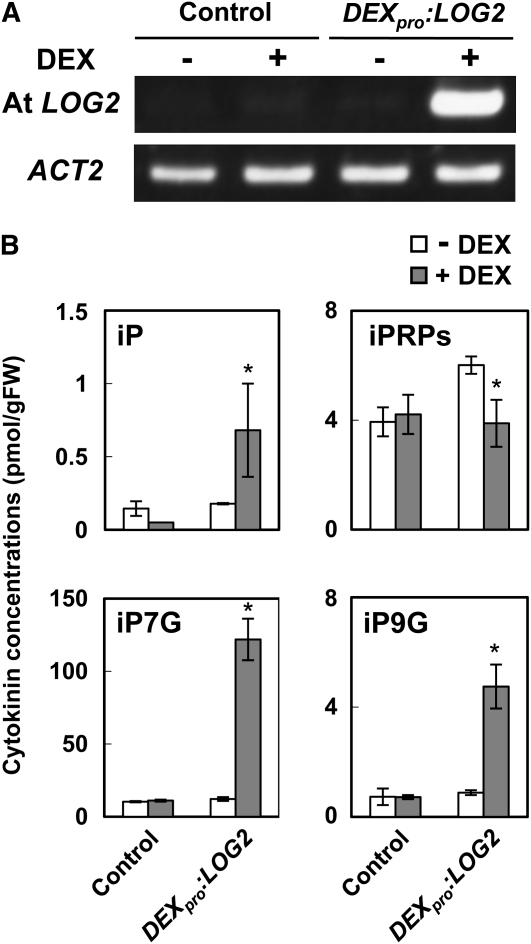

At LOGs Catalyze Cytokinin Activating Reaction in Vivo

To examine whether At LOGs catalyze cytokinin activation in vivo, transgenic Arabidopsis lines overexpressing At LOG1 to LOG5, and LOG8 under the control of a dexamethasone (DEX)-inducible promoter (DEXpro:LOG1 to DEXpro:LOG5, and DEXpro:LOG8, respectively) were generated. In DEXpro:LOG2, RT-PCR analyses showed strong transcriptional induction by DEX treatment (Figure 3A). In seedling roots treated with DEX for 5 d, accumulation of iPR phosphates (iPRPs) significantly decreased and that of iP increased (Figure 3B). On the other hand, accumulation levels of iPR did not change significantly (see Supplemental Table 2 online). Accumulation levels of iP-7-N-glucoside and iP-9-N-glucoside substantially increased in the DEX-treated plants, implying that a part of the overproduced iP was immediately inactivated by N-glucosyltransferases. Similar results were obtained in the other transgenic lines (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). These results strongly suggest that At LOGs catalyze the cytokinin-activating reaction in vivo.

Figure 3.

DEX-Inducible Overexpression of At LOG2 and Change in Cytokinin Levels.

Transgenic Arabidopsis seedlings harboring an empty pTA-7001 construct (Control) or DEXpro:LOG2 were grown for 17 d on MGRL-agar medium and then transplanted to MGRL-agar medium with or without 10 μM DEX. After 5 d, seedling roots were harvested, and RT-PCR analyses (A) and cytokinin content analyses (B) were performed. PCR reactions were performed with 25 and 22 temperature cycles for At LOG2 and ACT2, respectively. The ACT2 was used as a control. gFW, g fresh weight. Error bars represent the sd (n = 3). Data sets marked with an asterisk are significantly different from control as assessed by the Student's t test: P < 0.02. iP7G, iP-7-N-glucoside; iP9G, iP-9-N-glucoside.

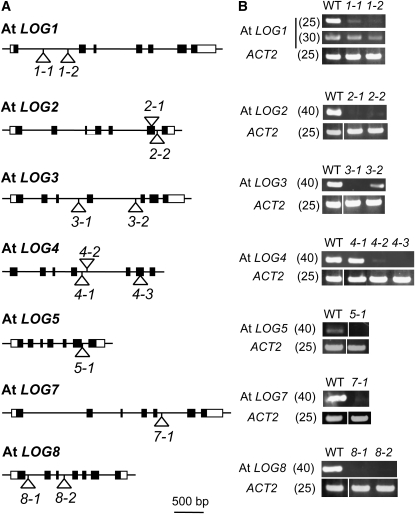

T-DNA Insertional Multiple Mutants, log2 log7 and log3 log4 log7, Are Less Sensitive to Cytokinin in Lateral Root Formation

In order to reveal the biological significance of the direct activation pathway mediated by LOGs in Arabidopsis, we isolated T-DNA inserted loss-of-function mutants for all At LOGs except for LOG6 and LOG9 (Figure 4A). RT-PCR analysis using primers amplifying full-length cDNAs was performed for each T-DNA insertional line. No PCR product was amplified from RNA of the mutants except for log1-1, log1-2, log3-2, log4-1, and log4-2 (Figure 4B). Detection of full-length transcripts in the five mutants indicates that the T-DNA inserted in these genes could be removed during RNA processing. We performed further analyses using log1-2, log2-1, log3-1, log4-3, log5-1, log7-1, and log8-2. We have omitted the allele numbers for these mutants in the following descriptions.

Figure 4.

T-DNA Insertional Mutants of At LOG Genes.

The T-DNA insertional mutants, logX-Y, are abbreviated as X-Y.

(A) Description of the mutant alleles used in this study. Black and white rectangles indicate protein coding regions and untranslated regions, respectively. T-DNA insert positions within the At LOGs are represented by open triangles.

(B) Expression of At LOG genes in wild-type and the mutant alleles. Total RNA prepared from 2-week-old seedlings grown on MGRL-agar medium was subjected to RT-PCR analysis. The ACT2 gene was used as a control. Cycle numbers for RT-PCR are shown in parentheses.

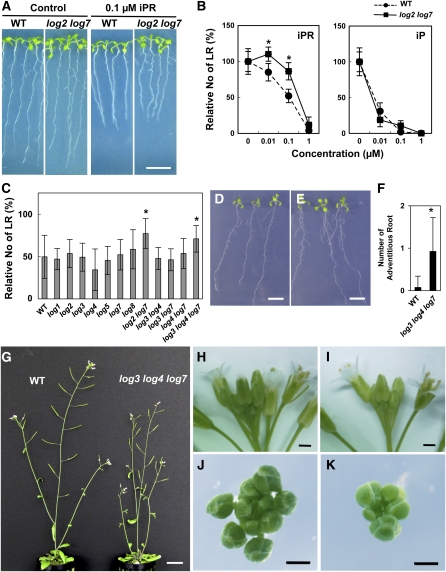

No single mutant exhibited a visible phenotype under normal growth conditions (data not shown). Therefore, we compared sensitivities of lateral root formation to cytokinin by exogenously applying iPR, a cytokinin nucleoside, in the single and multiple mutants. Cytokinin treatment inhibits the formation of lateral roots in Arabidopsis (Aloni et al., 2006). Because Arabidopsis roots secrete acid phosphatases (Trull and Deikman, 1998), it is assumed that cytokinin riboside 5′-monophosphate, the substrate of At LOGs, is not directly absorbed into plants. On the other hand, cytokinin nucleoside is absorbed and rapidly converted into the nucleotide and, to a lesser extent, into the nucleobase (Singh et al., 1988; Letham and Zhang, 1989; Jameson, 1994; Letham, 1994). In wild-type Arabidopsis seedlings, treatment with 0.1 μM iPR resulted in a significant decrease in the formation of lateral roots and a marked inhibition of primary root growth (Figures 5A and 5B); treatment with 1 μM iPR virtually eliminated the formation of lateral roots (Figures 5B). We examined the effect of iPR on lateral root formation in the T-DNA insertion mutants. In each single mutant, the sensitivity to iPR was not significantly changed in comparison to the wild type. We generated the double mutant of At LOG2 and LOG7, log2 log7, because these corresponding recombinant proteins showed high enzymatic activities (Table 1). log2 log7 showed significant resistance to iPR (Figures 5B and 5C). When seedlings were treated with 0.1 μM iPR, the inhibition of lateral root formation in log2 log7 was <20%, whereas the inhibition in the wild type was ∼50% (Figure 5B). No difference in the inhibitory effect of iP was observed between log2 log7 and the wild type (Figure 5B), indicating that sensitivity to cytokinin itself was not affected in the mutant. In addition, a triple mutant, log3 log4 log7, also showed significant resistance to exogenously applied iPR, whereas no significant resistance was observed in double mutants with any combinations of log3, log4, and log7 (Figure 5C). These results suggest that At LOG2, LOG3, LOG4, and LOG7 are redundantly responsible for cytokinin activation in the tissue adjacent to where lateral root formation occurs.

Figure 5.

Phenotypes of T-DNA Insertion Mutants of At LOG Genes.

(A) Seven-day-old seedlings of the wild type and log2 log7 grown on MGRL-agar medium with or without (Control) 0.1 μM iPR.

(B) Dose effect of iPR and iP on lateral root formation in the wild type (circles) and log2 log7 (squares). Seedlings were grown vertically on MGRL-agar medium for 11 d with the indicated concentrations of iPR or iP. Lateral roots visible with the aid of a magnifier were counted. The relative number of lateral roots (No of LR) was determined, with the number in the absence of iPR set as 100% for each genotype. The number of lateral roots without iPR was 15.8 ± 2.2 for the wild type and 16.8 ± 2.0 for log2 log7.

(C) Inhibitory effect of 0.1 μM iPR on lateral root formation in 12 Arabidopsis log mutants. The lateral root number of 11-d-old seedlings grown with or without 0.1 μM iPR was counted with the aid of a magnifier. The relative number of lateral roots (No of LR) was determined, with the number in the absence of iPR set as 100% for each genotype. The numbers of lateral roots without iPR were 11.8 ± 3.0 for the wild type, 12.3 ± 1.5 for log1, 12.4 ± 2.1 for log2, 9.9 ± 1.6 for log3, 11.4 ± 2.8 for log4, 13.4 ± 2.2 for log5, 12.5 ± 2.2 for log7, 11.1 ± 2.6 for log8, 12.4 ± 1.6 for log3 4, 11.5 ± 1.5 for log3 7, 14.1 ± 2.5 for log4 7, and 10.9 ± 1.7 for log3 4 7.

(D) and (E) Eleven-day-old seedlings of the wild type (D) and log3 log4 log7 (E) grown on MGRL-agar medium.

(F) Adventitious root formation in the log3 log4 log7 mutant. Wild-type and log3 log4 log7 seedlings were grown for 9 d on MGRL-agar medium, and the number of adventitious roots formed at root-hypocotyl junctions was counted.

(G) Five-week-old wild type (left) and log3 log4 log7 (right) grown on rockfiber blocks.

(H) to (K) Inflorescences of 4-week-old wild type [(H) and (J)] and log3 log4 log7 [(I) and (K)]. For (J) and (K), all opened flowers were removed from inflorescences.

Bars = 1 cm for (A), (D), and (E), 2 cm for (G), and 1 mm for (H) to (K). Error bars represent the sd (n > 7 for [B], n > 11 for [C], and n = 40 for [F]). Data sets marked with an asterisk are significantly different from the wild type as assessed by the Student's t test: P < 0.05.

A T-DNA Multiple Insertion Mutant, log3 log4 log7, Shows Altered Root and Shoot Morphology

Among recombinant At LOGs, LOG1, LOG3, LOG4, and LOG7 showed strong enzymatic activities (Table 1). We failed to isolate a null mutant of LOG1 (Figure 4B). Thus, to further analyze the function of LOGs in growth and development, a triple knock out mutant, log3 log4 log7, was generated. Although there was no visible phenotype in any double mutant combination of log3, log4, and log7 under normal growth conditions (data not shown), the log3 log4 log7 triple mutant showed altered root and shoot morphology. The log3 log4 log7 seedlings showed an increase in adventitious root formation in comparison to the wild type (Figures 5D to 5F), whereas there were no changes in the length of the primary root. At the reproductive stage, log3 log4 log7 showed a delay in inflorescence growth, resulting in decreased plant height (Figure 5G). The mutant log3 log4 log7 formed fewer flower buds and flowers than the wild type (Figures 5H to 5K), suggesting a reduced inflorescence meristem activity in log3 log4 log7. Transformation of a 7.6-kb fragment encompassing the genomic coding region of LOG7 including the putative promoter region into log3 log4 log7 fully rescued the reproductive stage phenotype (see Supplemental Figure 2 online), indicating that the observed phenotype of log3 log4 log7 is caused by cumulative effects of the mutations in LOG3, LOG4, and LOG7. Cytokinin measurement revealed that significantly increased levels of iPRPs accumulated, whereas those of iP decreased in log3 log4 log7 seedlings (see Supplemental Figure 3 online). These results strongly suggest that At LOG3, LOG4, and LOG7 are redundantly responsible for cytokinin activation in the course of normal root and shoot growth.

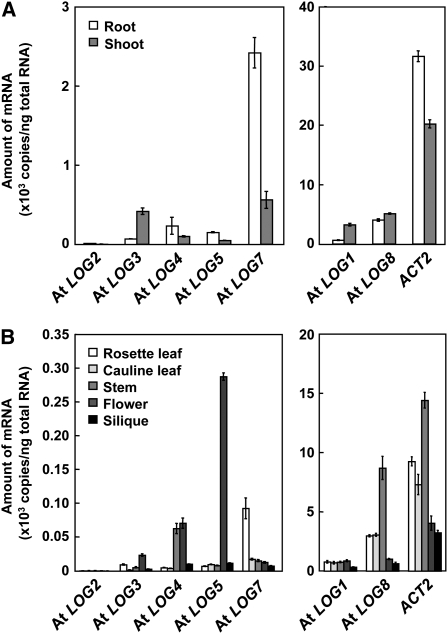

Expression Patterns of At LOG Genes

To evaluate the expression levels of LOGs in different organs, accumulation of LOG transcripts in each organ of Arabidopsis was analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR. In 2-week-old seedlings, the transcripts of all seven LOG genes were detected in both roots and shoots with different patterns and with the transcript of LOG8 being the most abundant (Figure 6A). In aerial organs of mature plants, the LOGs were differentially expressed; transcripts of LOG1 and LOG8 were abundant in all parts of the aerial organs examined, accumulation levels of LOG2 transcripts were extremely low, and transcripts of LOG4, LOG5, and LOG7 were more abundant in stem and flower, flower, and rosette leaf, respectively (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Expression Patterns of At LOGs.

(A) Accumulation patterns of LOG transcripts in Arabidopsis seedling roots and shoots. Total RNA prepared from roots and shoots of 2-week-old seedlings grown on MGRL-agar medium were subjected to quantitative RT-PCR.

(B) Accumulation patterns of LOG transcripts in aerial organs of mature plants. Total RNAs prepared from rosette leaves, cauline leaves, stems, flowers, and siliques of mature plants grown on rockwool blocks for 6 weeks were subjected to quantitative RT-PCR. Accumulation levels of the transcripts are given as the mRNA copy number per 1 ng total RNA. Real-time PCR was performed in triplicate, and the mean values with the sd are shown. ACT2 was used as an internal standard.

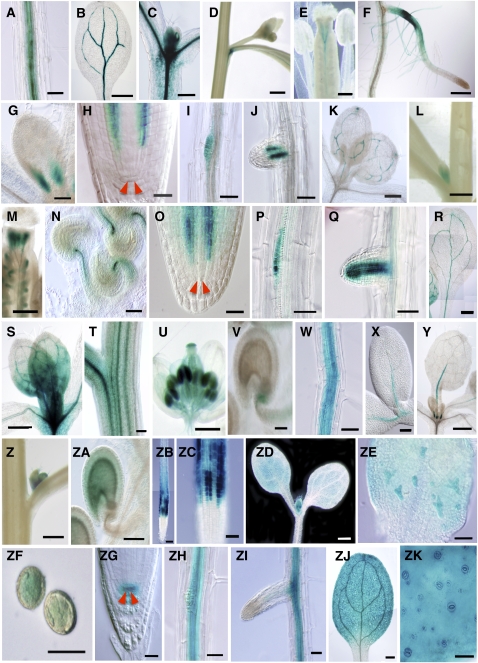

To investigate the detailed expression patterns of LOG genes, a series of transgenic plants harboring At LOG promoter:β-glucuronidase (GUS) chimeric genes fused at the second exon of each LOG, designated as LOG1pro:GUS, LOG2pro:GUS, LOG3pro:GUS, LOG4pro:GUS, LOG5pro:GUS, LOG7pro:GUS, and LOG8pro:GUS, were generated (see Supplemental Figure 4 online). In LOG1pro:GUS seedlings, GUS staining was detected in the vascular tissues of root (Figure 7A) and cotyledon (Figure 7B). Strong GUS expression was detected in the shoot apical region, including the meristem (Figure 7C). The GUS expression in the leaves was predominantly observed in immature vascular tissue (see Supplemental Figure 5A online). In stems of the adult plant, strong GUS expression was detected at the junction of the stem and cauline leaf (Figure 7D). In flowers, GUS expression was detected in immature flowers (see Supplemental Figure 5F online) and vascular tissues of pistils (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

GUS Expression Analysis of At LOG Gene Promoters.

(A) to (E) GUS expression in LOG1pro:GUS plants. GUS staining of mature primary root (A), cotyledon (B), shoot apical region (C) of 7-d-old seedlings, axillary bud (D), and pistil (E) of flowering plants are shown.

(F) and (G) GUS expression in LOG2pro:GUS plants. GUS staining of lateral root (F) and shoot apical region (G) of 7-d-old seedlings are shown.

(H) to (N) GUS expression in LOG3pro:GUS plants. GUS staining of the root tip (H), lateral root primordium (I), emerged lateral root (J), and shoot apical region (K) of 7-d-old seedlings, axillary bud (L), pistils (M), and ovules (N) of flowering plants are shown. Red arrowheads indicate quiescent center cells.

(O) to (V) GUS expression in LOG4pro:GUS plants. GUS staining of the root tip (O) of 1-d-old seedlings, lateral root primordium (P), emerged lateral root (Q), cotyledon (R), and shoot apical region (S) of 7-d-old seedlings, stem (T), immature flower (U), and ovule (V) of flowering plants are shown. Red arrowheads indicate quiescent center cells.

(W) to (ZA) GUS expression in LOG5pro:GUS plants. GUS staining of 9-d-old mature primary root (W), 1-d-old cotyledons (X), 9-d-old immature leaves (Y) of seedlings, axillary bud (Z), and ovule (ZA) of flowering plants are shown.

(ZB) to (ZF) GUS expression in LOG7pro:GUS plants. Root tips ([ZB] and [ZC]), shoot (ZD), and first leaf (ZE) of 7-d-old seedling and mature pollen (ZF) are shown. Magnified image of the elongation zone in (ZB) is shown as (ZC).

(ZG) to (ZK) GUS expression in LOG8pro:GUS plants. Root tip (ZG), mature primary root (ZH), emerged lateral root (ZI), cotyledon (ZJ), and epidermis of the cotyledon (ZK) of 9-d-old seedlings are shown. Red arrowheads indicate quiescent center cells.

Bars = 50 μm for (A), (I), (J), (P), (Q), (V), (W), (X), (ZA), (ZC), (ZE), (ZH), (ZI), and (ZK); 1 mm for (B), (D), and (L); 250 μm for (C), (E), (F), (K), (M), (S), and (ZJ); 100 μm for (G), (T), and (ZB); 25 μm for (H), (N), (O), (ZF), and (ZG); and 500 μm for (R), (U), (Y), (Z), and (ZD).

For LOG2pro:GUS, GUS expression was detected in root hairs and in the region of the primary root where root hairs form (Figure 7F). In shoots, GUS expression was observed only in the margins of the basal area of immature leaves (Figure 7G). In LOG3pro:GUS plants, GUS staining was detected in root procambium (Figure 7H), lateral root primordia (Figure 7I), and immature vascular tissues of lateral roots soon after emergence (Figure 7J). In shoots, GUS staining was detected in the vascular tissues of immature leaves (Figure 7K; see Supplemental Figure 5B online), axillary buds (Figure 7L), styles (Figure 7M; see Supplemental Figure 5G online), and ovular funiculus (Figure 7N).

Similar to the patterns expressed by LOG3pro:GUS plants, GUS expression in root procambium (Figure 7O), lateral root primordia (Figure 7P), and immature vascular tissues of lateral roots soon after emergence (Figure 7Q) was observed in LOG4pro:GUS expressing plants. In shoots, GUS expression was detected in the vascular tissue of cotyledons (Figure 7R). Strong GUS expression was detected in the shoot apical region, including the shoot apical meristem and in immature leaves as well for LOG1pro:GUS transgenic plants (Figure 7S; see Supplemental Figure 5C online). GUS expression was also detected in the vascular tissues of stems (Figure 7T), young inflorescences (Figure 7U; see Supplemental Figure 5H online), fruit abscission zones (see Supplemental Figure 5H online), and basal parts of ovules (Figure 7V).

GUS expression of LOG5pro:GUS transformants was observed in the vascular tissues of mature roots (Figure 7W). In seedlings, GUS expression was detected in the main cotyledonary veins soon after germination (Figure 7X) and in immature leaves (Figure 7Y; see Supplemental Figure 5D online). In flowering plants, GUS expression was detected in immature and mature flowers (see Supplemental Figure 5I online). GUS expression of LOG5pro:GUS plants was also observed within axillary buds (Figure 7Z) and ovules (Figure 7ZA).

For LOG7pro:GUS, strong GUS staining was observed in the epidermis of the root elongation zone (Figures 7ZB and 7ZC). In the seedling shoot, LOG7pro:GUS caused GUS expression throughout the cotyledon and immature leaves (Figure 7ZD) and in immature trichomes (Figure 7ZE). In the reproductive organs of LOG7pro:GUS plants, GUS was expressed in pollen (Figure 7ZF; see Supplemental Figure 5J online).

LOG8pro:GUS was expressed in the quiescent center of mature roots (Figure 7ZG) and mature root vascular tissue (Figures 7ZH and 7ZI). Expression in the quiescent center was not observed in immature lateral roots (Figure 7ZI). In seedlings of LOG8pro:GUS transformants, GUS was expressed in cotyledons, hypocotyls, and leaves, including the vascular tissue and stomata (Figures 7ZJ and 7ZK; see Supplemental Figure 5E online). In the reproductive organs of LOG8pro:GUS expressing plants, GUS was expressed in stems, flowers, and fruit abscission zones (see Supplemental Figure 5K online). These results strongly suggest that expression of the At LOGs is spatially and quantitatively differentiated but overlaps in some tissues (see Supplemental Table 3 online) and that active cytokinins can be synthesized via the direct activation pathway in nearly all parts of the plant body.

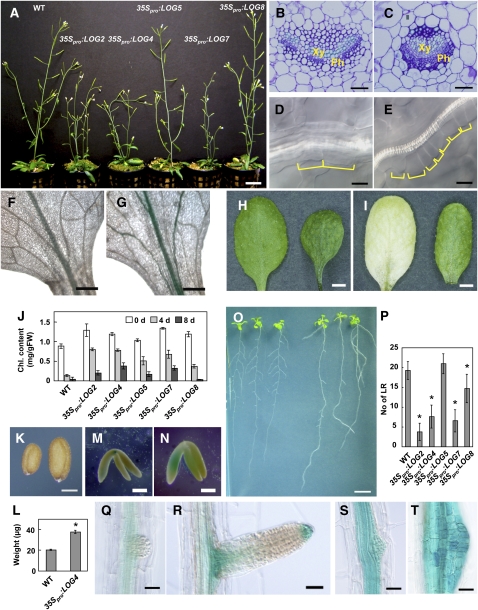

Constitutive Overexpression of At LOGs Shows Pleiotropic Phenotypes

To explore the consequences of elevated metabolic flow toward cytokinin activation mediated by LOGs, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis plants expressing At LOG2, LOG4, LOG5, LOG7, or LOG8 under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (35Spro:LOG2, 35Spro:LOG4, 35Spro:LOG5, 35Spro:LOG7, and 35Spro:LOG8, respectively). RT-PCR analyses showed that the 35S promoter–driven gene expression enhanced mRNA accumulation for each At LOG (see Supplemental Figure 6 online).

The 35Spro:LOG transgenic lines showed common and visible pleiotropic phenotypes at various developmental stages. The phenotypic changes were qualitatively similar for all genes, although the symptoms of 35Spro:LOG5 and 35Spro:LOG8 were less pronounced than others for some traits (details are described below). In shoots, 35Spro:LOG2, 35Spro:LOG4, and 35Spro:LOG7 showed a semidwarf phenotype with more axillary stems (Figure 8A), indicating a reduced shoot apical dominance in the transgenic lines.

Figure 8.

Phenotypes of 35Spro:LOG Transgenic Plants.

(A) Six-week-old plants. From left to right: wild-type, 35Spro:LOG2, 35Spro:LOG4, 35Spro:LOG5, 35Spro:LOG7, and 35Spro:LOG8 plants.

(B) and (C) Transverse sections of petioles from 3-week-old rosette leaves of wild-type (B) and 35Spro:LOG4 (C) seedlings. Xy, xylem; Ph, phloem.

(D) and (E) Bundle sheath cells of third rosette leaves from 3-week-old wild-type (D) and 35Spro:LOG4 (E) seedlings. Yellow lines indicate the length of individual bundle sheath cells.

(F) and (G) ARR5pro:GUS expression in third rosette leaves of the wild type (F) and 35Spro:LOG4 (G) background at 3 weeks after germination.

(H) to (J) Dark-induced senescence in a detached leaf assay. Third or fourth leaves of 21-d-old seedlings were detached and floated on distilled water.

(H) and (I) Leaves of the wild type (left) and 35Spro:LOG4 (right) after 0 d (H) or 4 d (I) of dark incubation.

(J) Leaf chlorophyll (Chl.) contents 0, 4, and 8 d after the dark incubation. Error bars represent the sd (n = 3).

(K) Mature seeds of wild-type (left) and the 35Spro:LOG4 (right) plants.

(L) Seed weight for wild-type and the 35Spro:LOG4 plants. The average weight of one seed was calculated from pools of 100 seeds. Error bars represent the sd (n = 3). Data sets marked with an asterisk are significantly different from the wild type as assessed by the Student's t test: P < 0.001.

(M) and (N) GUS-stained mature embryos of wild-type (M) and the 35Spro:LOG4 (N) plants in the ARR5pro:GUS background.

(O) Thirteen-day-old seedlings of wild-type (left) and the 35Spro:LOG4 (right) plants.

(P) Number of lateral roots (No of LR) in 13-d-old wild-type and 35Spro:LOG seedlings. The visible lateral roots were counted with the aid of a magnifier. Error bars represent the sd (n = 11). Data sets marked with an asterisk are significantly different from the wild type as assessed by the Student's t test: P < 0.01.

(Q) and (R) Initiating (Q) and emerging (R) lateral root of 3-week-old wild type in the ARR5pro:GUS background.

(S) and (T) GUS-stained initiating (S) and growth arrested (T) lateral root of 3-week-old 35Spro:LOG4 in the ARR5pro:GUS background.

Bars = 2 cm for (A), 50 μm for (B) and (C), 10 μm for (D) and (E), 0.5 mm for (F) and (G), 2 mm for (H) and (I), 250 μm for (K), 200 μm for (M) and (N), 1 cm for (O), and 50 μm for (Q) to (T).

Transverse sections through the central part of the fully developed third leaf of 35Spro:LOG4 seedlings showed that the cell density of vascular tissue increased in the dorsoventral direction, predominantly in the phloem (Figures 8B and 8C). The cell number per unit length of bundle sheath increased in comparison to that of the wild type (Figures 8D and 8E). These results suggest that the meristem activity of leaf vascular tissue increased in the transgenic lines. When we crossed 35Spro:LOG4 with cytokinin-responsive ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR5 (ARR5) promoter:GUS transgenic line (D'Agostino et al., 2000), GUS activity increased in the vascular tissues in the 35Spro:LOG4 background in comparison with the wild type (Figures 8F and 8G). This suggests that enhancing cytokinin signaling in vascular tissues results in increased cell division activity.

Chlorophyll contents of 35Spro:LOG leaves increased 10 to 30% relative to the wild type (Figures 8H and 8J). When the detached rosette leaves of 35Spro:LOG4 plants were kept under dark conditions, the transgenic leaves showed a retardation of senescence (Figures 8I and 8J). After a 4-d dark treatment, 60 to 70% of the chlorophyll remained in 35Spro:LOG2, 35Spro:LOG4, 35Spro:LOG5, and 35Spro:LOG7 plants, whereas only 20% of the chlorophyll remained in the wild type (Figure 8J).

The mature viable seeds of 35Spro:LOG2, 35Spro:LOG4, 35Spro:LOG5, 35Spro:LOG7, and 35Spro:LOG8 plants were larger than the wild-type seeds (Figure 8K; see Supplemental Figure 7 online). The weight of 35Spro:LOG4 seeds was approximately twice that of wild-type seeds (Figure 8L). In late-stage embryos of 35Spro:LOG4 in the ARR5pro:GUS background, embryos were enlarged and GUS expression was enhanced relative to the wild type (Figures 8M and 8N), suggesting that enhanced cytokinin signaling results in larger embryos. The cotyledon size of 35Spro:LOGs transformants was also larger than that of the wild type (see Supplemental Figures 8A to 8C online). Cell area of the cotyledon palisade tissue of 35Spro: LOG4 was comparable to the wild type (see Supplemental Figures 8D online), whereas cell number was significantly higher (see Supplemental Figure 8E online), suggesting that the larger seed phenotype is attributable to enhanced cell division during embryo development.

The F1 seeds produced by 35Spro:LOG4 flowers pollinated with wild-type pollen were as large as 35Spro:LOG4 seeds produced by self-pollination. By contrast, the seed size of F1 progeny produced by pollination in the reciprocal combination was similar to that of the wild type (see Supplemental Table 4 online). When we crossed heterozygous 35Spro:LOG4 flowers with wild-type pollen, the F1 seeds showed an intermediate seed size (see Supplemental Table 4 online). These results indicate that cytokinin activity in the ovule-bearing sporophyte is a determinant of seed size.

The length of the primary root was similar between 35Spro:LOG and wild-type seedlings grown on MGRL-agar medium, but the number of emerged lateral roots decreased in 35Spro:LOG2, 35Spro:LOG4, 35Spro:LOG7, and 35Spro:LOG8 seedlings (Figures 8O and 8P). Detailed observations of 35Spro:LOG4 in the ARR5pro:GUS background revealed an enhancement of cytokinin signaling and abnormal proliferation of lateral root primordia, whose further development was arrested (Figures 8Q to 8T).

To confirm the functionality of overexpressed At LOG in planta, we measured cytokinin concentrations in the seedlings of 35Spro:LOG4. In the roots, the concentrations of iPRPs and tZRPs were significantly lower, and those of iP, tZ, and the glucosides were higher than the wild type (see Supplemental Figure 9 online). In the shoots, however, although iP-type species showed a pattern similar to the roots, the levels of tZRPs, tZ, and the O-glucoside were all lower than the wild type.

At LOG-Green Fluorescent Protein Fusions Localized in the Cytosol and Nucleus

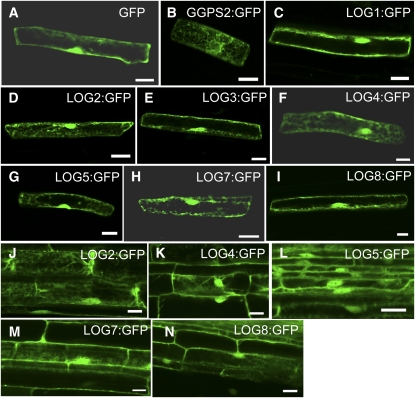

In rice, LOG:green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein localized to the cytosol as shown by transient expression in onion epidermal cells (Kurakawa et al., 2007). To determine the subcellular localization of At LOG proteins, we fused GFP to the C termini of At LOG1 to LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 (LOG1:GFP to LOG5:GFP, LOG7:GFP, and LOG8:GFP, respectively) and transiently expressed the fusion proteins in Arabidopsis root cells. As is the case with untargeted GFP, the At LOG:GFP fluorescence signals showed typical distribution patterns in the cytosol and nuclei (Figures 9A to 9I).

Figure 9.

Subcellular Localization of LOG:GFP Proteins.

(A) to (I) Subcellular localization of fusion proteins (GFP [A], GGPS2:GFP [B], LOG1:GFP [C], LOG2:GFP [D], LOG3:GFP [E], LOG4:GFP [F], LOG5:GFP [G], LOG7:GFP [H], and LOG8:GFP [I]) transiently expressed in Arabidopsis root cells by particle bombardment. GFP was used as the control marker for cytosol and nuclear localizations; Arabidopsis geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 2 (GGPS2):GFP was used as a marker for endoplasmic reticulum localization.

(J) to (N) Subcellular localization of fusion proteins (LOG2:GFP [J], LOG4:GFP [K], LOG5:GFP [L], LOG7:GFP [M], and LOG8:GFP [N]) in Arabidopsis root cells constitutively expressed by the 35S promoter.

Bars = 20 μm.

To elucidate whether the At LOG:GFP fusion proteins were functional in planta, we expressed these fusion proteins under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter in stably transformed Arabidopsis plants. The transgenic lines expressing individual LOG2, LOG4, LOG5, LOG7, or LOG8:GFP fusion genes showed essentially the same localization patterns as those demonstrated by transient assays (Figures 9J to 9N).

DISCUSSION

We undertook a detailed analysis of seven At LOG genes encoding cytokinin-activating enzymes in Arabidopsis. Our study revealed biochemical properties, spatial distribution, and pleiotropic effects of loss-of-function and gain-of-function modulations of At LOGs on morphology and cytokinin metabolism.

Biochemical Properties of LOG Proteins

As is the case with rice LOG (Kurakawa et al., 2007), in vitro and in vivo analyses demonstrated that the LOGs are involved in the direct activation pathway of cytokinins in Arabidopsis. At LOG1, LOG3, LOG4, and LOG7 showed similar substrate affinities (Km) and catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) as rice LOG (Table 1). The substrate affinity of LOG2 was less than that of other At LOGs, but the higher kcat value compensated for it and helped to maintain the catalytic efficiency (Table 1). In addition, strong phenotypes in the overexpression lines of LOG2, LOG4, and LOG7 (Figure 8; see Supplemental Figure 7 online) also point to a function in a direct activation pathway of cytokinins.

LOG5 and LOG8 have relatively low catalytic efficiencies (Table 1). The stable and ectopic overexpression of LOG5 and LOG8 also showed weaker phenotypes in some traits (Figure 8; see Supplemental Figure 7 online), whereas DEX-inducible overexpression of LOG5 and LOG8 showed similar changes in cytokinin metabolism to those of other At LOGs (see Supplemental Figure 1 online). These lines of evidence strongly suggest that all seven LOGs function in the synthesis of bioactive cytokinins in Arabidopsis, although we cannot fully exclude the possibility that LOG5 and LOG8 are also involved in other unknown metabolic pathways. The optimal pH of LOG5 is a little acidic in comparison to others (Table 1). Thus, the weaker phenotype might be due to a difference in pH where LOG5 was ectopically expressed. Since LOG8 was expressed more strongly than other At LOGs (Figures 6 and 7; see Supplemental Figure 5 online), the expression strength might have compensated for the weakness of its enzyme reactivity.

Occurrence of aromatic cytokinins has been reported in Arabidopsis (Tarkowská et al., 2003). Different substrate specificities to benzyladenine riboside 5′-monophosphate (Figure 2) imply that there are functional differences among At LOGs in regulating aromatic cytokinin activation, although the biological relevance of aromatic cytokinin metabolism in Arabidopsis has not been elucidated.

Decrease in Sensitivity to Cytokinin Nucleoside in Multiple Mutants of At LOGs

The inhibitory effect of iPR on lateral root formation was relieved in log2 log7 and log3 log4 log7 mutants (Figures 5A to 5C). iPR displays much less affinity for cytokinin receptors than iP (Yamada et al., 2001; Romanov et al., 2006), indicating that the inhibitory effect of iPR on lateral root formation was accomplished by the conversion from iPR to bioactive forms in planta. No recombinant At LOG reacted with iPR, and accumulation levels of iPR were not changed after LOG2 induction by DEX application (see Supplemental Table 2 online). These lines of evidence suggest that At LOGs do not react with iPR in planta. Exogenously applied cytokinin nucleosides are immediately converted to the nucleotides following uptake (Singh et al., 1988; Letham and Zhang, 1989; Jameson, 1994; Letham, 1994). Thus, it is plausible that the inhibitory effect of iPR on lateral root formation was accomplished not by direct conversion of iPR to iP but by indirect conversion from iPR to iP via iPRMP. LOG2 and LOG7 are expressed in the epidermis of the elongation and root hair zones, whereas LOG3 and LOG4 are expressed in vascular tissues and lateral root primordia (Figure 7). It has been reported that cytokinins regulate root meristem size in the transition zone (Dello Ioio et al., 2007) and that cytokinins act directly on lateral root founder cells to inhibit root initiation in pericycle cells adjacent to the xylem poles (Li et al., 2006; Laplaze et al., 2007). LOG2, LOG3, LOG4, and LOG7 could be involved in converting iPRMP to iP in these tissues to regulate lateral root initiation and development.

Altered Shoot and Root Morphology in a Triple Mutant of At LOGs

The log3 log4 log7 mutant showed defects in shoot growth at the reproductive stage, whereas root growth was enhanced (Figures 5D to 5K). These phenotypes are partially similar to those of transgenic plants overexpressing At CKX (Werner et al., 2003) and multiple loss-of-function mutants of At IPTs (Miyawaki et al., 2006). This result strongly suggests that the direct pathway of cytokinin activation via At LOGs is a dominant pathway for normal growth and development.

The log3 log4 log7 mutant showed enhanced growth of adventitious roots, whereas there was no significant effect on the primary root (Figures 5D to 5F). Overexpression of At CKX resulted in similar phenotypes (Werner et al., 2003), suggesting that adventitious roots are more sensitive to changes of cytokinin activity than are primary roots.

log3 log4 log7 showed a semidwarf phenotype and formed fewer flowers than the wild type (Figures 5G to 5K), suggesting a reduced activity of the inflorescence meristem. Overexpression of At CKX leads to reduced meristem activity in shoots (Werner et al., 2003). Multiple mutants of Arabidopsis genes related to cytokinin signaling also show a reduction in meristem activity in shoots (Higuchi et al., 2004; Nishimura et al., 2004; Hutchison et al., 2006; Riefler et al., 2006). Our results support the conclusions from these previous findings that cytokinins positively regulate shoot meristem activity in Arabidopsis.

It has been reported that overexpression of At CKX leads to an inhibition of vascular development and increased seed size (Werner et al., 2003). However, no significantly altered phenotype with respect to vascular development and seed size was observed in log3 log4 log7, suggesting that there is higher degree of redundancy in the function of LOGs for vascular development and the regulation of embryogenesis.

None of the single mutants of At LOG genes exhibited a visible phenotype. In rice, mutations in LOG cause premature termination of the shoot meristem (Kurakawa et al., 2007). Our results suggested that Arabidopsis has a higher redundancy in the function of LOGs than rice at least as far as the maintenance of shoot apical meristems is concerned. However, since no null mutant of At LOG1 is available (Figure 4B), we cannot exclude that At LOG1 by itself plays an important role in growth and development.

Spatial Localization of At LOGs

At LOG:GFP fusion proteins localized in the cytosol and nuclei (Figure 9). Analysis with At IPT:GFP fusion proteins showed that IPT1, IPT3, IPT5, and IPT8 were found in plastids, IPT7 was targeted to mitochondria, and IPT4 was localized in the cytosol (Kasahara et al., 2004). Experiments with stable isotope-labeled substrates indicate that plastids are a major subcellular compartment for the initial step in cytokinin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seedlings (Kasahara et al., 2004). In addition, adenosine kinase, which catalyzes conversion from cytokinin nucleosides to the nucleotides (Kwade et al., 2005), does not have an apparent signal sequence for organellar translocation. These findings imply the existence of a transport system associated with organelles that can translocate cytokinin nucleotides or nucleosides to the cytosol.

Our histochemical analyses of LOGspro:GUS plants revealed the spatial distribution of the direct activation pathway in Arabidopsis (Figure 7; see Supplemental Table 3 online). Superimposition of the expression patterns of At LOGs and At IPTs (Miyawaki et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004b) revealed that some of the expression sites of LOGs and IPTs overlap, such as lateral root primordia, fruit abscission zones, ovules, and root and leaf vascular tissues. These spatial distribution patterns suggest that the cytokinin nucleotides are synthesized by IPTs in these restricted sites and are activated locally by LOGs to act as autocrine or paracrine signals. On the other hand, expression of LOGs was observed in root hairs, the epidermis of the root elongation zone, and mature flowers (Figure 7; see Supplemental Figure 5 online), in which expression of At IPTs was not observed (Miyawaki et al., 2004; Takei et al., 2004b). The differences in expression patterns between At IPTs and LOGs also suggest that a portion of cytokinin precursors is translocated from cell to cell and/or over a long range before becoming the active forms.

Pleiotropic Phenotypes of 35Spro:LOG Plants

The overexpression of At LOG genes resulted in relatively mild phenotypes compared with that of IPT genes (Zubko et al., 2002; Sun et al., 2003; Sakamoto et al., 2006). This might indicate that At LOG enzymes are not rate limiting for de novo cytokinin synthesis and that their regulatory function might be less essential. In rosette leaves of 35Spro:LOG4 plants, the cell numbers of vascular tissues increased (Figures 8B to 8E). Overexpression of At CKX and multiple mutants of cytokinin receptors show reduced cell numbers for leaf vascular tissues and a decreased density in leaf veins, respectively (Werner et al., 2003; Nishimura et al., 2004). Our result supports a role for cytokinins in promoting cambial activity (Matsumoto-Kitano et al., 2008). In addition, overexpression of At LOG4 increased the number of phloem cells (Figures 8B and 8C), supporting the idea that cytokinin negatively regulates protoxylem specification (Mähönen et al., 2006). By contrast, the increased chlorophyll content and delay of senescence in 35Spro:LOGs leaves (Figures 8I and 8J) support a function for cytokinins as regulators of leaf longevity (Kim et al., 2006).

The 35Spro:LOG plants showed a semidwarf phenotype with more axillary stems (Figure 8A), whereas the multiple mutant log3 log4 log7 also showed a similar phenotype (Figures 5G to 5K). This result suggests that cell division activity or size of the floral meristem was reduced in both plants. At present, we cannot provide a single reason for the phenotype of 35Spro:LOG plants. One possible explanation may reflect differences in the biological roles of iP and tZ. In shoots of 35Spro:LOG4 plants, accumulation levels of tZ-type cytokinins were reduced (see Supplemental Figure 9 online). This result is probably due to excess consumption of iPRMP by overexpressing LOG4, resulting in decreased metabolic flow to the tZ-type species. tZ, not iP, might be a main factor for maintenance of floral meristem activity.

35Spro:LOG plants set larger seeds than those of the wild type (Figure 8K; see Supplemental Figure 7 online). This phenotype is attributable to the enhancement of cytokinin activation in ovule-bearing sporophytes (see Supplemental Table 4 online). On the other hand, it was reported that constitutive activation of cytokinin signaling at the embryonic heart stage by expressing ARR10 (D69E), a type-B response regulator, results in enlarged embryos (Müller and Sheen, 2008). Since the 35S promoter is not active in early embryogenesis (Custers et al., 1999), the increased size of embryos in 35Spro:LOG plants might be caused by nonautonomous effects in the ovule-bearing sporophytes that showed enhancement of cytokinin activation. However, enlarged embryos were also observed in transgenic plants overexpressing At CKX (Werner et al., 2003) and in multiple loss-of-function mutants of At IPTs (Miyawaki et al., 2006) and other components of cytokinin signaling (Hutchison et al., 2006; Riefler et al., 2006). The reasons for this discrepancy remain to be clarified. During embryo development, appropriate levels of cytokinin activity in ovule-bearing sporophytes might be important for normal seed set.

In an apparent inhibition of lateral root formation in LOG overexpression lines (Figures 8O and 8P), disciplined cell division did not occur after the formation of lateral root primordia (Figures 8S and 8T). A similar phenotype was observed following cytokinin treatment (Laplaze et al., 2007) and conditional overexpression of IPT (Kuderová et al., 2008), suggesting that cytokinins are involved in both the initiation and patterning of lateral root primordia.

Biological Importance of the Direct Activation Pathway in Arabidopsis

Our study demonstrated that cytokinin activation by the direct pathway in Arabidopsis is regulated by seven members of a small family of LOG genes. Pleiotropic phenotypes of 35Spro:LOG plants, whose metabolic flow toward activation is enhanced, shows that the activation step is a key regulatory step of cytokinin activity. At present, the responsible genes for the two-step activation pathway have not been identified. Uridine-ribohydrolase 1 (URH1), recently isolated from Arabidopsis, might be a candidate because it shows the nucleosidase activity toward iPR. URH1 also reacts with uridine, inosine, and adenosine with higher affinities in comparison to iPR (Jung et al., 2009). Further studies will provide an answer for the biological relevance of URH1 in cytokinin metabolism.

Morphological and metabolic analyses of increasing and decreasing LOG activities suggested that the direct pathway via LOGs is the major pathway for cytokinin activation and is pivotal for normal growth and development in Arabidopsis. Partially overlapping expression patterns of the LOG genes and no visible phenotype of single log mutants suggest that At LOGs play redundant functions during plant development. To confirm the importance of cytokinin activation via LOG, phenotypic analyses and tracer analyses with labeled cytokinin metabolites using higher orders of multiple loss-of-function mutants of At LOGs are needed.

METHODS

Plant Material and Growth Condition

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0) was used as the wild-type plant. T-DNA insertional mutants of log1-1 (SALK_027495), log1-2 (SALK_143462), log2-1 (SALK_052856), log2-2 (SALK_147463), log3-1 (SALK_056659), logt3-2 (SALK_066969), log4-1 (SALK_045912), and log4-2 (SALK_137667), log4-3 (SALK_092241), log7-1 (SALK_113173), log8-1 (SALK_090077), and log8-2 (SALK_093520) were obtained from the ABRC (http://www.biosci.ohio-state.edu/∼plantbio/Facilities/abrc/abrchome.htm). A T-DNA insertional mutant of log5-1 (GABI_002G02) was obtained from GABI-Kat (http://www.gabi-kat.de/). All mutants were derived from the Col-0 ecotype. Genotypes were determined by PCR with gene- and T-DNA–specific primers (see Supplemental Table 5 and Supplemental Data Set 2 online). Seeds of ARR5pro:GUS (D'Agostino et al., 2000) were obtained from the ABRC.

Arabidopsis plants were grown on rockwool blocks (Rock Fiber; Nittobo) or agar medium at 22°C, under fluorescent illumination at an intensity of ∼70 μmol m−2 s−1 with a photoperiod of 16 h light/8 h dark. For phenotypic analysis on MGRL salt medium (Fujiwara et al., 1992), 1% (w/v) agar and 1% (w/v) sucrose were added (MGRL-agar plates). For selection of transgenic plants, half-strength MS salt (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) medium was supplemented with 0.8% (w/v) agar, 1% (w/v) sucrose, and appropriate antibiotics.

Phylogenetic Analysis

Full-length amino acid sequences were aligned (see Supplemental Data Set 3 online) using the default setting of ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). A phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA 4.0 program (http://www.megasoftware.net) using the default setting of the neighbor-joining method (Saitou and Nei, 1987). Bootstrap analysis was conducted with 1000 replicates.

Cloning of cDNAs

The coding regions from LOG1 to LOG9 were amplified from cDNA of 3-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on MGRL-agar medium. Total RNA of Arabidopsis was prepared using an RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen) with oligo(dT)12–18 primers. The primers used for the PCR were LOGs-RT-F and LOGs-RT-R for At LOGs (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). Each PCR product was cloned into the pCRII-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced to confirm the sequence fidelity.

Recombinant Enzymes

The coding regions from LOG1 to LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 were amplified from Arabidopsis cDNA. The primers used for the PCR were LOGs-pCold-F and LOGs-pCold-R for At LOGs (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). The PCR products were ligated into the pCOLD-I vector (Takara) to express His-tagged recombinant proteins. The BL21 (DE3) strain harboring pG-Tf2 (Takara) was used as the Escherichia coli host. Expression of the recombinant proteins was induced in modified M9 medium (Blackwell and Horgan, 1991) with 1 mM isopropyl-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 24 h at 16°C. After induction, E. coli cells were sonicated, and the crude protein extracts were passed through a Ni-NTA Superflow column (Qiagen) to purify recombinant proteins according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Enzyme Assay

Purified rice (Oryza sativa) LOG (Kurakawa et al., 2007) and At LOGs recombinant proteins were incubated in 100 μL of reaction mixture (50 mM Tris-HCl at their optimum pH shown in Table 1, 1 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM DTT) with each substrate at 30°C. The reaction was stopped by the addition of three reaction volumes of acetone and centrifuged at 15,000g for 20 min. The supernatant was collected and evaporated to remove acetone. After dilution with 2% acetic acid, the sample was subjected to reverse-phase chromatography (Waters; Symmetry C18; 4.6 mm × 150 mm) on an HPLC system (Waters; model 600/717plus/PDA996). Other conditions were as described previously (Takei et al., 2001b). The Km values were calculated using Lineweaver-Burk plots. One unit of LOG activity was defined as the amount of enzyme that produced 1 μmol of nucleobase per minute under the conditions of the reaction.

Transgenic Arabidopsis Expressing At LOGs through the Glucocorticoid-Induced GVG System

The cDNA of At LOG1 to LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 were amplified by PCR with primers LOGs-DEX-F and LOGs-DEX-R (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). The cDNAs were ligated into the pTA7001 vector (Aoyama and Chua, 1997) to yield constructs containing the DEX-inducible At LOGs, designated as DEXpro:LOGs. The chimeric genes were introduced into wild-type Arabidopsis by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Eight or more lines for each construct were tested for DEX effects; at least three lines for each construct showed clear growth inhibition in the presence of 10 μM DEX. All analyses for CK were performed with T3 homozygous progeny, which showed growth inhibition in the 10 μM DEX treatment.

RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA extractions, cDNA synthesis, and PCR amplifications were performed using the same procedure as described for cloning of At LOG cDNAs. The primers used for PCR were as follows: LOGs-RT-F and LOGs-RT-R for At LOGs, ACT2-RT-F and ACT2-RT-R for ACTIN2 (ACT2) as control (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). Aliquots of the reactions were separated on 0.8% (w/v) agarose gels and stained with ethidium bromide.

Quantification of Cytokinins

Extraction and determination of cytokinin contents from ∼100 mg of plant tissue was performed using a liquid chromatography–tandem mass chromatography system (Waters; AQUITY UPLC System/Quattro Ultima Pt) as described (Kojima et al., 2009).

Complementation Analysis

For a complementation test of the log3 log4 log7 mutant, two 3.8-kb fragments were amplified from the Arabidopsis genome by PCR with primers LOG7-COM-Fs and LOG7-COM-Rs (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). The resulting fragments were cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and ligated using the EcoRI site for production of a 7.6-kb fragment encompassing the genomic region of the LOG7 gene as well as the putative promoter region. The fragment was integrated into the GATEWAY destination vector, pBG, using LR clonase (Invitrogen). The resulting plasmid pBG-LOG7 was introduced into log3 log4 log7 by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Eleven independent T1 plants were used for complementation analysis.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) with RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen). cDNA was synthesized using SuperScript III RT (Invitrogen) with oligo(dT)12–18 primers. The quantitative RT-PCR was performed on an ABIPRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems) by monitoring the amplification with SYBR-Green I dye (Applied Biosystems). Plasmid DNA containing the corresponding cDNAs was used as a template to generate a calibration curve. The primers used for PCR were as follows: LOGs-QRT-F and LOGs-QRT-R for At LOGs; ACT2-QRT-F and ACT2-QRT-R for ACT2 (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online).

Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Harboring the LOGpro:GUS Fusions

LOGpro:GUS fusions were prepared as shown in Supplemental Figure 4 online. For the construction of LOGpro:GUS fusions, the fragments including each promoter through a part of the second exon of LOG1 to LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 were amplified from the Arabidopsis genome by PCR. The primers used for PCR were as follows: LOGs-GUS-F and LOGs-GUS-R for LOG2, LOG3, LOG4, and LOG5pro:GUS fusions; LOGs-GUS-F1 and -R1 and LOGs-GUS-F2 and -R2 for LOG1, LOG7, and LOG8pro:GUS fusions (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). Resulting fragments for LOG1, LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8pro:GUS fusions were inserted into the vector pBI101 (Jefferson et al., 1987) upstream of the GUS reading frame. For LOG2, LOG3, and LOG4pro:GUS fusions, each fragment was subcloned into the pENTR/D/TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and then integrated into the GATEWAY binary vector, pBGGUS (Kubo et al., 2005), using LR clonase (Invitrogen). The resulting chimeric genes were introduced into Arabidopsis by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). T2 or T3 transformants were used for GUS assay. GUS staining patterns were examined in at least 20 lines per construct, and staining patterns were characterized in at least three lines.

Histological Analysis and GUS Assay

For observation of bundle sheath cells, samples were fixed in a solution containing a 9:1 (v/v) mixture of ethanol and acetic acid. The rehydrated samples were dissected under water, mounted in chloral hydrate:glycerol:water (8:3:1, w/v/v), and viewed under an Olympus BX51 microscope (Olympus) equipped with Nomarski optics. For transverse sections, the samples were embedded in Technovit 7100 resin (Heraeus Kulzer) after fixation with ethanol. Sections were cut using an ultramicrotome (Yamato Kohki; PR-50) and were stained with toluidine blue O. Observations were made using an Olympus BX51 microscope.

For detection of GUS activity, samples except for roots were first placed in 90% acetone on ice for 15 min and in reaction buffer solution [500 μg/mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-glucuronide cyclohexylammonium salt, 100 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, 0.5 mM K3Fe(CN)6, 0.5 mM K4Fe(CN)6, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Triton X-100] at 37°C. They were transferred into 70% ethanol. Samples of inflorescences were directly observed with an Olympus SZX12 stereomicroscope (Olympus). Samples of seedlings were mounted in water or chloral hydrate:glycerol:water (8:3:1, w/v/v) and viewed with an Olympus BX51 microscope equipped with or without Nomarski optics, respectively.

Transgenic Arabidopsis Plants Constitutively Overexpressing At LOG Genes

The cDNA of the At LOG2, LOG4, LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 genes were amplified by PCR with primers LOGs-35S-F and LOGs-35S-R (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). All cDNA sequences were ligated into the pBI121 vector (Jefferson et al., 1987). The chimeric genes were introduced into Arabidopsis by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Phenotypes of transgenic plants were observed in at least 20 lines per construct. At least three lines for each construct showed strong phenotypes. All analyses for CK were performed with T3 homozygous progeny that showed strong phenotypes.

Chlorophyll Retention Assay

Arabidopsis seedlings were grown on rockwool block for 21 d. The third and fourth leaves were excised and floated on distilled water in microplates. The plates were incubated in the dark or light for the indicated period. Three samples were measured for each genotype, with each sample consisting of two leaves. Chlorophyll was extracted with ethanol overnight. Light absorption at 649 and 665 nm was determined with a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu; UV-1650 PC), normalized to fresh weight, and the chlorophyll contents were calculated as described (Wintermans and de Mots, 1965).

Analyses of GFP Fusion Proteins

For construction of plasmids for particle bombardment, cDNAs of At LOG1 to LOG5, LOG7, and LOG8 were amplified by PCR with primers LOGs-GFP-F and LOGs-GFP-R (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online) and fused to the N terminus of the sGFP (S65T) vector (Niwa et al., 1999), whose expression was controlled by the cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (35Spro:GFP). The resulting DNA constructs were introduced into root cells of 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings by particle bombardment (Bio-Rad; PDU-1000/He). The 35Spro:GFP empty vector was used for the control marker of cytosol and nuclei; signal peptide of Arabidopsis geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase 2 fused to sGFP driven by 35S promoter (35Spro:GGPS2:GFP) (Okada et al., 2000) was used for the control marker of endoplasmic reticulum localization. Transient expression was observed by confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy (Olympus; Fluoview IX5) after overnight incubation.

For construction of plasmids for stable transformants, cDNAs of At LOG2:GFP, LOG4:GFP, LOG5:GFP, LOG7:GFP, and LOG8:GFP were amplified by PCR from each plasmid for particle bombardment with primers LOGs-GFPS-F and GFPS-R (see Supplemental Data Set 2 online). Each product was ligated into the pBI121 vector (Jefferson et al., 1987). The chimeric genes were introduced into Arabidopsis by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Phenotypes of transgenic plants were observed in at least 20 lines per construct. At least three lines for each construct showed strong phenotypes. Expression of At LOG:GFP fusion proteins in each T1, T2, or T3 transformant with strong phenotype was observed by confocal laser scanning fluorescence microscopy.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: Arabidopsis sequences: At LOG1, At2g28305; At LOG2, At2g35990; At LOG3, At2g37210; At LOG4, At3g53450; At LOG5, At4g35190; At LOG6, At5g03270; At LOG7, At5g06300; At LOG8, At5g11950; At LOG9, At5g26140; and ACT2, At3g18780. Rice sequences: LOG, Os01g0588900; LOGL1, Os01g0708500; LOGL2, Os02g0628000; LOGL3, Os03g0109300; LOGL4, Os03g0697200; LOGL5, Os03g0857900; LOGL6, Os04g0518800; LOGL7, Os05g0541200; LOGL8, Os05g0591600; LOGL9, Os09g0547500; and LOGL10, Os10g0479500. Moss (Physcomitrella patens) sequences: XP 001754473, XP 001761321, XP 001762334, XP 001767304, XP 001769707, XP 001769708, XP 001777597, XP 001777598, and XP 001781548.

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure 1. DEX-Inducible Overexpression of At LOG Genes and Change of Cytokinin Levels.

Supplemental Figure 2. Complementation of the log3 log4 log7 Mutant by the At LOG7 Gene.

Supplemental Figure 3. Cytokinin Levels in the log3 log4 log7 Mutant.

Supplemental Figure 4. Schematic Representation of LOGpro:GUS Fusion Constructs.

Supplemental Figure 5. GUS Expression in Seedlings and Inflorescences of LOGpro:GUS Transgenic Plants.

Supplemental Figure 6. Overexpression of At LOG Genes in 35Spro:LOG Transgenic Lines.

Supplemental Figure 7. Seed Length of the 35Spro:LOG Transgenic Plants.

Supplemental Figure 8. Phenotypes of 35Spro:LOG Cotyledons and Leaves.

Supplemental Figure 9. Cytokinin Levels in Roots and Shoots of 35Spro:LOG4 Transgenic Plants.

Supplemental Table 1. Structural Features of At LOGs and Proteins.

Supplemental Table 2. Change of iP-Type Cytokinin Concentrations in Roots of DEXpro:LOG2 Transgenic Plants.

Supplemental Table 3. Summary of GUS Expression Patterns in LOGpro:GUS Transgenic Plants.

Supplemental Table 4. Genetic Regulation of Seed Size by the 35Spro:LOG4 Transgene.

Supplemental Table 5. T-DNA Insertion Sites and Primers Used for This Study.

Supplemental Data Set 1. cDNA Sequences of At LOG6 and At LOG9 Genes.

Supplemental Data Set 2. Primer Sequences Used for This Study.

Supplemental Data Set 3. Alignment Used for Phylogenetic Analysis of LOG and Homologs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Takatoshi Kiba (RIKEN) for his critical reading of this manuscript. We also thank the ABRC and GABI-Kat for providing seeds of T-DNA insertion lines and ARR5pro:GUS lines, Yasuo Niwa (University of Shizuoka, Shizuoka, Japan) for providing the 35Spro:GFP (S65T) vector, Nam-Hai Chua (The Rockefeller University, New York) for providing the pTA-7001 vector, Kazunori Okada (University of Tokyo, Japan) for providing the 35Spro:GGPS2:GFP vector, Taku Demura (RIKEN) for providing the pBGGUS and pBG vectors, Mitsutaka Araki (RIKEN) for DNA sequencing, Kentaro Takei (RIKEN) for providing primers and plasmid of the ACT2 gene, and Masami Nanri, Hiromi Ojima, Kayo Yoshida-Hatanaka, Nobue Makita (RIKEN), and Katerina Slovalova (Palacly University, Czech) for technical assistance. This work was partly supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (Start-up [number 18870027 to T.K.] and B [number 20770043 to T.K.]) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The author responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (www.plantcell.org) is: Hitoshi Sakakibara (sakaki@riken.jp).

Online version contains Web-only data.

Open access articles can be viewed online without a subscription.

References

- Allen, M., Qin, W., Moreau, F., and Moffatt, B. (2002). Adenine phosphoribosyltransferase isoforms of Arabidopsis and their potential contributions to adenine and cytokinin metabolism. Physiol. Plant. 115 56–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aloni, R., Aloni, E., Langhans, M., and Ullrich, C.I. (2006). Role of cytokinin and auxin in shaping root architecture: Regulating vascular differentiation, lateral root initiation, root apical dominance and root gravitropism. Ann. Bot. (Lond.) 97 883–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama, T., and Chua, N.H. (1997). A glucocorticoid-mediated transcriptional induction system in transgenic plants. Plant J. 11 605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argueso, C.T., Ferreira, F.J., and Kieber, J.J. (2009). Environmental perception avenues: The interaction of cytokinin and environmental response pathways. Plant Cell Environ. 32 1147–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, J.R., and Horgan, R. (1991). A novel strategy for production of a highly expressed recombinant protein in an active form. FEBS Lett. 295 10–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.M. (1997). Cytokinin biosynthesis and interconversion. Physiol. Plant. 101 665–673. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-M., and Kristopeit, S.M. (1981. a). Metabolism of cytokinin: Dephosphorylation of cytokinin ribonucleotide by 5′-nucleotidases from wheat germ cytosol. Plant Physiol. 67 494–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.-M., and Kristopeit, S.M. (1981. b). Metabolism of cytokinin: deribosylation of cytokinin ribonucleoside by adenosine nucleosidase from wheat germ. Plant Physiol. 68 1020–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough, S.J., and Bent, A.F. (1998). Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbesier, L., Prinsen, E., Jacqmard, A., Lejeune, P., Van Onckelen, H., Périlleux, C., and Bernier, G. (2003). Cytokinin levels in leaves, leaf exudate and shoot apical meristem of Arabidopsis thaliana during floral transition. J. Exp. Bot. 54 2511–2517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Custers, J.B.M., Snepvangers, S.C.H.J., Jansen, H.J., Zhang, L., and Campagne, M.M.V. (1999). The 35S-CaMV promoter is silent during early embryogenesis hut activated during nonembryogenic sporophytic development in microspore culture. Protoplasma 208 257–264. [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino, I.B., Deruere, J., and Kieber, J.J. (2000). Characterization of the response of the Arabidopsis response regulator gene family to cytokinin. Plant Physiol. 124 1706–1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dello Ioio, R., Linhares, F.S., Scacchi, E., Casamitjana-Martinez, E., Heidstra, R., Costantino, P., and Sabatini, S. (2007). Cytokinins determine Arabidopsis root-meristem size by controlling cell differentiation. Curr. Biol. 17 678–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara, T., Hirai, M.Y., Chino, M., Komeda, Y., and Naito, S. (1992). Effects of sulfur nutrition on expression of the soybean seed storage protein genes in transgenic petunia. Plant Physiol. 99 263–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galuszka, P., Popelková, H., Werner, T., Frébortová, J., Pospisilova, H., Mik, V., Köllmer, I., Schmülling, T., and Frébort, I. (2007). Biochemical characterization of cytokinin oxidases/dehydrogenases from Arabidopsis thaliana expressed in Nicotiana tabacum L. J. Plant Growth Regul. 26 255–267. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, M., et al. (2004). In planta functions of the Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 8821–8826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose, N., Takei, K., Kuroha, T., Kamada-Nobusada, T., Hayashi, H., and Sakakibara, H. (2008). Regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis, compartmentalization and translocation. J. Exp. Bot. 59 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou, B., Lim, E.K., Higgins, G.S., and Bowles, D.J. (2004). N-glucosylation of cytokinins by glycosyltransferases of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 279 47822–47832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houba-Herin, N., Pethe, C., d'Alayer, J., and Laloue, M. (1999). Cytokinin oxidase from Zea mays: Purification, cDNA cloning and expression in moss protoplasts. Plant J. 17 615–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchison, C.E., Li, J., Argueso, C., Gonzalez, M., Lee, E., Lewis, M.W., Maxwell, B.B., Perdue, T.D., Schaller, G.E., Alonso, J.M., Ecker, J.R., and Kieber, J.J. (2006). The Arabidopsis histidine phosphotransfer proteins are redundant positive regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell 18 3073–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, P.E. (1994). Cytokinin metabolism and compartmentation. In Cytokinins, D.W.S. Mok and M.C. Mok, eds (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), pp. 113–128.

- Jefferson, R.A., Kavanagh, T.A., and Bevan, M.W. (1987). GUS fusions: Beta-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. EMBO J. 6 3901–3907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, B., Flörchinger, M., Kunz, H.H., Traub, M., Wartenberg, R., Jeblick, W., Neuhaus, H.E., and Möhlmann, T. (2009). Uridine-ribohydrolase is a key regulator in the uridine degradation pathway of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 21 876–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakimoto, T. (2001). Identification of plant cytokinin biosynthetic enzymes as dimethylallyl diphosphate:ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases. Plant Cell Physiol. 42 677–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara, H., Takei, K., Ueda, N., Hishiyama, S., Yamaya, T., Kamiya, Y., Yamaguchi, S., and Sakakibara, H. (2004). Distinct isoprenoid origins of cis- and trans-zeatin biosyntheses in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 279 14049–14054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.J., Ryu, H., Hong, S.H., Woo, H.R., Lim, P.O., Lee, I.C., Sheen, J., Nam, H.G., and Hwang, I. (2006). Cytokinin-mediated control of leaf longevity by AHK3 through phosphorylation of ARR2 in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103 814–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, M., Kamada-Nobusada, T., Komatsu, H., Takei, K., Kuroha, T., Mizutani, M., Ashikari, M., Ueguchi-Tanaka, M., Matsuoka, M., Suzuki, K., and Sakakibara, H. (2009). Highly sensitive and high-throughput analysis of plant hormones using MS-probe modification and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: an application for hormone profiling in Oryza sativa. Plant Cell Physiol. 50 1201–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, M., Udagawa, M., Nishikubo, N., Horiguchi, G., Yamaguchi, M., Ito, J., Mimura, T., Fukuda, H., and Demura, T. (2005). Transcription switches for protoxylem and metaxylem vessel formation. Genes Dev. 19 1855–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuderová, A., Urbánková, I., Válková, M., Malbeck, J., Brzobohaty, B., Némethová, D., and Hejátko, J. (2008). Effects of conditional IPT-dependent cytokinin overproduction on root architecture of Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 49 570–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurakawa, T., Ueda, N., Maekawa, M., Kobayashi, K., Kojima, M., Nagato, Y., Sakakibara, H., and Kyozuka, J. (2007). Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature 445 652–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwade, Z., Swiatek, A., Azmi, A., Goossens, A., Inzé, D., Van Onckelen, H., and Roef, L. (2005). Identification of four adenosine kinase isoforms in tobacco By-2 cells and their putative role in the cell cycle-regulated cytokinin metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 280 17512–17519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laplaze, L., et al. (2007). Cytokinins act directly on lateral root founder cells to inhibit root initiation. Plant Cell 19 3889–3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letham, D.S. (1994). Cytokinins as phytohormones-sites of biosynthesis, translocation, and function of translocated cytokinin. In Cytokinins: Chemistry, Activity, and Function, D.W.S. Mok and M.C. Mok, eds (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press), pp. 57–80.

- Letham, D.S., and Zhang, R. (1989). Cytokinin translocation and metabolism in lupin species. II. New nucleotide metabolites of cytokinins. Plant Sci. 64 161–165. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Mo, X., Shou, H., and Wu, P. (2006). Cytokinin-mediated cell cycling arrest of pericycle founder cells in lateral root initiation of Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol. 47 1112–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mähönen, A.P., Bishopp, A., Higuchi, M., Nieminen, K.M., Kinoshita, K., Tormakangas, K., Ikeda, Y., Oka, A., Kakimoto, T., and Helariutta, Y. (2006). Cytokinin signaling and its inhibitor AHP6 regulate cell fate during vascular development. Science 311 94–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.C., Mok, M.C., Habben, J.E., and Mok, D.W. (2001). A maize cytokinin gene encoding an O-glucosyltransferase specific to cis-zeatin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98 5922–5926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.C., Mok, M.C., and Mok, D.W. (1999. a). Isolation of a cytokinin gene, ZOG1, encoding zeatin O-glucosyltransferase from Phaseolus lunatus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96 284–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]