Abstract

Background and purpose:

Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (ICl(Ca)) in arterial smooth muscle cells are inhibited by phosphorylation. The Ca2+-activated Cl− channel (ClCa) blocker niflumic acid (NFA) produces a paradoxical dual effect on ICl(Ca), causing stimulation or inhibition at potentials below or above 0 mV respectively. We tested whether the effects of NFA on ICl(Ca) were modulated by phosphorylation.

Experimental approach:

ICl(Ca) was elicited with 500 nM free internal Ca2+ in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes. The state of global phosphorylation was altered by cell dialysis with either 5 mM ATP or 0 mM ATP with or without an inhibitor of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II, KN-93 (10 µM).

Key results:

Dephosphorylation enhanced the ability of 100 µM NFA to inhibit ICl(Ca). This effect was attributed to a large negative shift in the voltage-dependence of block, which was converted to stimulation at potentials <−50 mV, ∼70 mV more negative than cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP. NFA dose-dependently blocked ICl(Ca) in the range of 0.1–250 µM in cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and KN-93, which contrasted with the stimulation induced by 0.1 µM, which converted to block at concentrations >1 µM when cells were dialysed with 5 mM ATP.

Conclusions and implications:

Our data indicate that the presumed state of phosphorylation of the pore-forming or regulatory subunit of ClCa channels influenced the interaction of NFA in a manner that obstructs interaction of the drug with an inhibitory binding site.

Keywords: Calcium-activated chloride channels, vascular smooth muscle, niflumic acid, phosphorylation, state-dependent block

Introduction

The membrane depolarization associated with the opening of Ca2+-activated Cl− channels (ClCa) is thought to be an important contributor to the development of vascular smooth muscle tone induced by constricting hormones and neurotransmitters (Large and Wang, 1996; Leblanc et al., 2005). Among several classes of agents, the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, niflumic acid (NFA) has been extensively used as a ‘relatively’ selective blocker of ClCa channels in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (Large and Wang, 1996). At concentrations in the range of ∼1–50 µM, NFA blocks Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (ICl(Ca)) evoked by L-type Ca2+ current (Yuan, 1997), reverse-mode Na+/Ca2+ exchange (Leblanc and Leung, 1995), constricting agonists or caffeine (Hogg et al., 1994), spontaneous transient inward Cl− currents (STICs) triggered by spontaneous release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) (Hogg et al., 1994; Janssen and Sims, 1994; Greenwood and Large, 1995; ZhuGe et al., 1998), or flash photolysis of caged Ca2+ (Clapp et al., 1996). Within the same concentration range, NFA has no effect on the magnitude of Ca2+ current (Pacaud et al., 1989; Lamb et al., 1994; Yuan, 1997), swelling-activated Cl− current (Greenwood and Large, 1998), KCl-induced contractions (Criddle et al., 1996; 1997; Yuan, 1997; Lamb and Barna, 1998; Remillard et al., 2000), or SR Ca2+release evoked by caffeine or norepinephrine (Hogg et al., 1994).

The effects of NFA on VSMC ClCa channels are complex, with a wide range of IC50 values reported for blockade of these channels. A close examination of the studies that have investigated the effects of NFA on ICl(Ca) suggests that its potency appears to be linked to the method used to evoke the current. Indeed, the IC50 for inhibiting STICs was <4 µM (Hogg et al., 1994) whereas the affinity of NFA for blocking ICl(Ca) evoked by an agonist or caffeine was at least twofold lower (Hogg et al., 1994). Although dose–response relationships were not obtained, NFA appeared less efficacious at inhibiting arterial ICl(Ca) elicited by inward Ca2+ current than STICs with 10 µM NFA producing ∼50–80% of the deactivating Cl− tail current recorded after return to the holding potential (HP) (Lamb et al., 1994; Yuan, 1997). A further reduction in potency was evident during NFA-induced block of ICl(Ca) evoked by elevated sustained intracellular Ca2+ concentration (500 nM) in coronary myocytes with an IC50 at +50 mV of 159 µM (Ledoux et al., 2005). One possible explanation of these observations may relate to the ability of higher [Ca2+]i, either induced cyclically or maintained, to promote downregulation of ICl(Ca) by phosphorylation via calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II (CaMKII) (Wang and Kotlikoff, 1997; Greenwood et al., 2001; 2004; Ledoux et al., 2003; Angermann et al., 2006).

The present study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that the presumed state of phosphorylation of ClCa channel influences their pharmacology.To this end, we tested the effects of NFA on ICl(Ca) evoked by 500 nM internal Ca2+ in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes dialysed with either 5 mM ATP to induce global phosphorylation, or in the absence of ATP with or without the CaMKII inhibitor KN-93, to promote dephosphorylation of the channel or a regulatory protein (Angermann et al., 2006). At positive potentials, the block displayed steep voltage dependence that was markedly attenuated in conditions favouring global dephosphorylation. On the other hand, ClCa channels suppressed by conditions promoting global phosphorylation exhibited enhanced stimulation by NFA at negative potentials. These results demonstrate that the presumed state phosphorylation of the pore-forming or regulatory subunit of ClCa channels has a profound influence on the interaction of NFA with these channels, which may explain the wide range of sensitivities of these channels to NFA reported in many earlier studies.

Methods

Isolation of rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the University of Nevada Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The animals were allowed free access to food and water and kept on a 12–12 h light/dark cycle. Smooth muscle cells were isolated as described earlier (Greenwood et al., 2004; Angermann et al., 2006). In brief, cells were prepared from the main and secondary pulmonary arterial branches dissected from New Zealand white rabbits (2–3 kg) killed by anaesthetic overdose. After dissection and removal of connective tissue, the pulmonary arteries were cut into small strips and incubated overnight (∼16 h) at 4°C in a low Ca2+ physiological salt solution (PSS; see composition below) containing either 10 or 50 µM CaCl2 and ∼1·mg·mL−1 papain, 0.15·mg·mL−1 dithiothreitol and 1·mg·mL−1 bovine serum albumin. The next morning, the tissue strips were rinsed three times in low Ca2+ PSS and incubated in the same solution for 5 min at 37°C. Cells were released by gentle agitation with a wide bore Pasteur pipette, and then stored at 4°C until used (within 10 h following dispersion).

Whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiology

Ca2+-activated Cl−currents were elicited using the conventional whole-cell configuration of the patch clamp technique with a pipette solution containing either 0 mM ATP with KN-93 (a specific inhibitor of CaMKII) or 5 mM ATP. The pipette solution also contained 10 mM BAPTA as the Ca2+ buffer and free [Ca2+] was set to 500 nM by the addition of 7.08 mM CaCl2. The free [Ca2+] was estimated by the calcium chelator program WinMaxC (v. 2.50; http://www.stanford.edu/~cpatton/downloads.htm). Using a Ca2+-sensitive electrode and calibrated solutions, the total amounts of CaCl2 and MgCl2 calculated by the software were previously shown to yield accurate free Ca2+ concentrations with both EGTA and BAPTA as Ca2+ buffers (Ledoux et al., 2003; Greenwood et al., 2004; Angermann et al., 2006). Contamination of ICl(Ca) from other types of current was minimized by the use of CsCl and tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) in the pipette solution, and TEA in the external solution. Data for each group were collected in cells from at least two animals but generally more.

Experimental protocols

ICl(Ca) was evoked immediately upon rupture of the cell membrane and the voltage-dependent properties were monitored every 5 or 10 s by stepping from a HP of −50 mV to +90 mV for 1 s, followed by repolarization to −80 mV for 1 s. Current–voltage (I–V) relationships were constructed by stepping in 10 mV increments from HP to test potentials between −100 mV and +140 mV for 1 s after 10 min dialysis. For I–V relationships, ICl(Ca) was expressed as current density (pA/pF) by dividing the amplitude of the current measured at the end of the voltage clamp step by the cell capacitance. For all figure panels showing a time course of ICl(Ca) changes, the late current measured at +90 mV was normalized to the amplitude of first current elicited at time = 0 (∼30 s after breaking the seal and measuring cell capacitance). After measuring cell capacitance, the constant step protocol described above was started to monitor the changes of ICl(Ca) over the course of 10 min after which a control I–V relationship was obtained. While monitoring ICl(Ca) elicited by a similar constant step protocol described above, the external solution was switched to one containing NFA at a concentration of 0.1, 1, 10, 100 or 500 µM. During these experiments, cells were stepped from the HP to +80 mV before being repolarized to −80 mV. After a steady-state effect was noticed, another I–V relationship was obtained in the presence of NFA. If the seal was still stable, washout was subsequently initiated and an I–V curve generated after washout. Only one concentration of NFA was tested per cell.

Solutions

Single pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells were isolated by incubating pulmonary artery tissue strips in the following low Ca2+ (10 or 50 µM) PSS (in mM): NaCl (120), KCl (4.2), NaHCO3 (25; pH 7.4 after equilibration with 95% O2 5% CO2 gas), KH2PO4 (1.2), MgCl2 (1.2), glucose (11), taurine (25), adenosine (0.01) and CaCl2 (0.01 or 0.05). The K+-free bathing solution used in all patch clamp experiments had the following composition (in mM): NaCl (126), HEPES-NaOH (10, pH 7.35), TEA (8.4), glucose (20), MgCl2 (1.2) and CaCl2 (1.8). The pipette solution had the following composition (in mM): TEA (20), CsCl (106), HEPES-CsOH (10, pH 7.2), BAPTA (10), ATP.Mg (0 or 5), GTP.diNa (0.2) and KN-93 (0 or 0.01). To this solution, the following total amounts of CaCl2 and MgCl2 were added to set free [Mg2+] at 0.5 mM and free [Ca2+] at various desired levels: 5 mM ATP and 500 nM Ca2+(in mM): CaCl2 (7.08), MgCl2 (3.0); no ATP and 500 nM Ca2+: CaCl2 (7.08), MgCl2 (0.545).

Statistical analysis

All data were pooled from n cells taken from at least two different animals with error bars representing the SEM. All data were first pooled in Excel and means exported to Origin 7.5 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) for plotting and curve fitting. All graphs and current traces were exported to CorelDraw 12 (Ottawa, ON, Canada) for final processing of the figures. Origin 7.5 software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) was also used to determine the statistical significance between two groups using a paired or unpaired Student's t-test, or one-way anova test followed by Bonferroni post hoc multiple range tests in multiple group comparisons. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Materials

All enzymes, analytical grade reagents and NFA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). NFA was initially prepared as 1, 10 or 100 mM stock in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) and an appropriate aliquot was added to the external solution to reach the final desired concentration. The maximal concentration of DMSO never exceeded 0.1%, a concentration that had no effect on ICl(Ca).

Results

Effect of global phosphorylation status on Ca2+-activated Cl− current

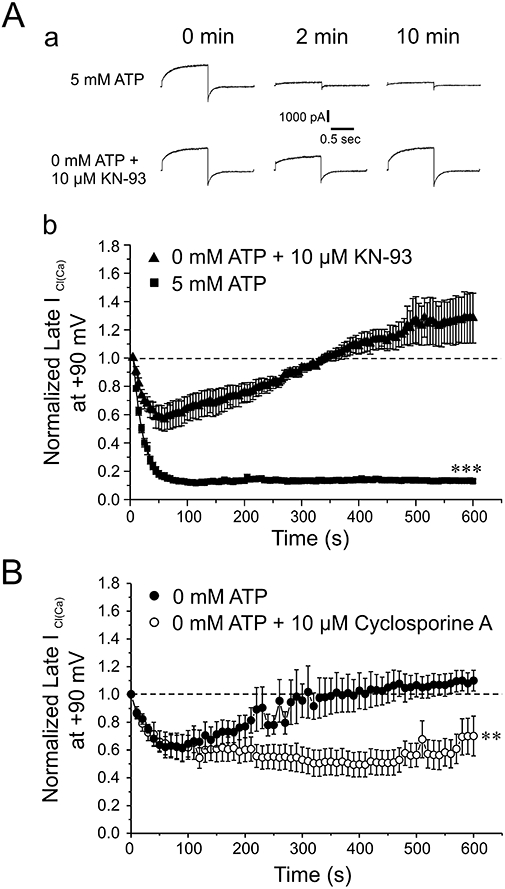

In all experiments we systematically dialysed the cells for 10 min with 5 mM ATP, or 0 mM ATP with or without 10 µM KN-93, a specific inhibitor of CaMKII. KN-93 was added to facilitate a presumed state of dephosphorylation of the channel or regulatory subunit by endogenous phosphatases. As previously shown by our group (Greenwood et al., 2001; 2004; Angermann et al., 2006), these conditions allowed us to first establish conditions favouring completely different states of cellular phosphorylation before examining the effects of NFA on Ca2+-activated Cl− current (ICl(Ca)) evoked by 500 nM free intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Figure 1A-a shows current traces recorded at different times after seal rupture from two sample experiments under the conditions described above. ICl(Ca) was evoked by 1 s steps to +90 mV from an HP of −50 mV which was followed by a 1 s repolarizing step to −80 mV before returning to the HP. As previously shown by our group (Greenwood et al., 2001; 2004; Angermann et al., 2006), step depolarization to +90 mV induced an initial instantaneous membrane current after the capacitative current that was followed by a slow time-dependent current component, both arising from basal and voltage-dependent gating properties of Ca2+-activated Cl−channels. A slow tail current was apparent upon repolarization to −80 mV and is consistent with channel closure caused by voltage-dependent deactivation. Immediately after seal rupture (0 min), ICl(Ca) evoked in both conditions displayed similar amplitude and kinetics. ICl(Ca) exhibited marked rundown during the first 2 min and remained suppressed throughout the initial 10 min of cell dialysis with 5 mM ATP. Removal of ATP and inclusion of KN-93 to suppress CaMKII activity in the pipette solution also resulted in ICl(Ca) rundown but the magnitude of this process was clearly attenuated after 2 min. This initial rundown is most likely to reflect a partial state of phosphorylation of an unknown regulatory or pore-forming subunit because of consumption of endogenous levels of ATP before depletion ensues. With continued dialysis, ICl(Ca) progressively recovered and eventually exceeded (see traces at 10 min) the amplitude of the initial current recorded at the onset of dialysis. The graph in Figure 1A-b shows mean data obtained from 32 or 42 cells in each group. For each data set, the amplitude of ICl(Ca) recorded at the end of the step to +90 mV was normalized to that of the initial current recorded at time = 0. Consistent with the experiment described in Figure 1A-a, ICl(Ca) exhibited marked rundown after breaking the seal with 5 mM ATP reaching ∼15% of the initial level in less than 2 min, a level that remained very stable throughout the rest of the experiment. As in Figure 1A, removing ATP and the addition of KN-93 from the pipette attenuated the rundown and resulted in a complete recovery that continued to develop beyond the initial level (∼30% above the initial level). The global state of phosphorylation also affected deactivation kinetics, where removal of ATP from the pipette solution caused a slowing of the time constant from 70.5 ± 3.4 ms (n= 42) to 101.9 ± 6.1 ms (n= 32; P < 0.001), with 5 mM ATP and no ATP and 10 µM KN-93 respectively. An opposite trend was observed for the activation kinetics although the differences were just at the limit of significance; τ for activation was 322.9 ± 11.1 ms for 5 mM ATP (n= 42) and 300.5 ± 14.1 ms for 0 mM ATP with KN-93 (n= 32; P= 0.0576). The effects of different ATP levels on ICl(Ca) are very similar to those reported by Angermann et al. (2006) who proposed that phosphorylation causes a state-dependent block of the channels. Another series of experiments was carried out to further demonstrate that changing ATP levels influenced an important phosphorylation step regulating ICl(Ca). Figure 1B shows that removing ATP alone also attenuated rundown ICl(Ca) and led to a recovery of the current that still exceeded the initial level after 10 min but to a lesser extent (∼10% instead of 30%) than when KN-93 was included in the pipette solution. As shown in Figure 1B including cyclosporine A in the pipette solution, a specific inhibitor of the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase calcineurin (Klee et al., 1998; Rusnak and Mertz, 2000), prevented the recovery of ICl(Ca). These experiments established that the very different characteristics of ICl(Ca) before any exposure to NFA was carried out were dictated by diametrically opposed states of global phosphorylation.

Figure 1.

Attenuation of rundown of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit pulmonary artery myocytes by minimizing phosphorylation. (A-a) Representative current traces demonstrate the time-dependent changes of Ca2+-activated Cl− current recorded from pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells dialysed with either 5 mM ATP or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93. Currents depicted were recorded immediately following breaking the seal (0 min), and after 2 and 10 min of cell dialysis. The currents were elicited by repetitive 1 s step depolarizations (every 5 s) to +90 mV from a holding potential (HP) of −50 mV. Each depolarizing pulse was followed by a repolarizing step to −80 mV to enhance the magnitude of the tail current. (A-b) This graph depicts the mean time course of ICl(Ca) amplitude elicited by 1 s depolarizing pulses to +90 mV, followed by 1 s repolarizing steps to −80 mV, in the presence of 5 mM ATP (n= 42), or with 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93 (n= 32). Currents were normalized to the initial current amplitude at the beginning of the protocol. Each step was applied from HP =−50 mV at a frequency of one pulse every 5 s for 10 min. ***Significantly different from cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and 10 µM KN-93; P < 0.001. (B) This graph shows the mean time course of changes of late ICl(Ca) measured at the end of 1 s steps to +90 mV from HP =−50 mV (one step every 10 s) in cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP, with (n= 4) or without (n= 5) 10 µM cyclosporine A to inhibit calcineurin. **Significantly different from cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and 10 µM cyclosporine A; P < 0.01.

Global state of dephosphorylation enhances the potency of NFA-induced block of ICl(Ca)

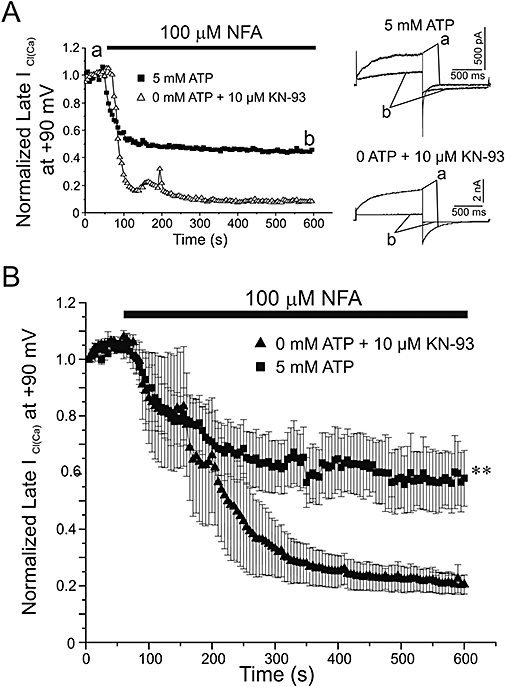

The next series of experiments were conducted to determine whether NFA exerts a differential effect on ICl(Ca) when the state of global phosphorylation is altered. Figure 2A depicts typical experiments in which the effects of 100 µM NFA were tested on ICl(Ca) recorded from a cell dialysed with 5 mM ATP, and 0 mM ATP and 10 µM KN-93 respectively. The superimposed traces shown to the right of the graph were obtained immediately before (labelled a) and after steady-state block achieved by NFA (labelled b). The voltage clamp protocol used was similar to that of Figure 1, with changes outlined in the Methods section. The graph shows the two superimposed time courses of normalized ICl(Ca) amplitude before and during the application of NFA. In both cases, NFA blocked the instantaneous and time-dependent components of ICl(Ca) but the amount of inhibition was notably increased for the cell dialysed with 0 mM ATP and KN-93. Figure 2B shows plots of mean normalized ICl(Ca) at +90 mV as a function of time for similar experiments performed with a pipette solution containing 5 mM ATP or 0 mM ATP and KN-93. Although the time course of block of ICl(Ca) by NFA was similar in both groups, the ATP-free pipette solution containing KN-93 clearly enhanced the potency of the drug. On average NFA blocked ICl(Ca) by 42 ± 10% with 5 mM ATP and 80 ± 3% with no ATP + KN-93. These results demonstrate that inhibition of ICl(Ca) mediated by a presumed state channel or regulatory subunit phosphorylation reduces the ability of NFA to inhibit the channels.

Figure 2.

Effect of phosphorylation on the ability of NFA to block ICl(Ca). (A) Representative time courses from pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells dialysed with pipette solutions containing either 5 mM ATP or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93. Currents were measured at the end of 1 s depolarizing steps to +90 mV from HP =−50 mV and plotted against time over a 10 min period of dialysis. Following current stabilization, 100 µM NFA was applied to the cells, as indicated by the filled bar. Corresponding to points (a) and (b) on the time courses, superimposed sample traces taken before (a) and after (b) the application of NFA are shown to the right of the graph for each experiment. (B) Time courses representing mean data collected as described above for cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP (n= 10) or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93 pipette solution (n= 5). **Significantly different from 5 mM ATP with P < 0.01.

We next examined the voltage dependence of interaction of NFA under both conditions (Figure 3). On the left hand side of each panel, typical families of ICl(Ca) currents recorded from the same cell in control (top) and after exposure to 100 µM NFA for 10 min (bottom) are shown. For each panel, the graph on the right hand side reflects the mean I–V relationships of ICl(Ca) density registered at the end of 1 s steps ranging from −100 to +140 mV from HP =−50 mV and obtained before and after the application of NFA. Consistent with phosphorylation-induced changes in ClCa channel gating (Greenwood et al., 2001; 2004; Ledoux et al., 2003; Leblanc et al., 2005; Angermann et al., 2006), control currents recorded with 5 mM ATP (Figure 3A) were considerably smaller (note the different calibration bars), and displayed slower activation and faster deactivation kinetics than those obtained in the absence of ATP (Fig. 3B). For both groups of cells, NFA blocked instantaneous and time-dependent outward ICl(Ca) (>0 mV) but the block was greater with 0 mM ATP and KN-93 (Figure 3B) than with 5 mM ATP (Figure 3A). NFA was previously shown to enhance ICl(Ca) in the negative range of membrane potentials (Piper et al., 2002). The same group also reported marked rebound stimulation of the current in the entire range of membrane potentials examined during washout of the drug and a similar observation was also made for ICl(Ca) in rabbit coronary myocytes (Ledoux et al., 2005). The insets in the graphs displayed in Figure 3 represent an expanded scale in the negative range of voltages of the I–V relationships of ICl(Ca) density. The results confirm that NFA stimulated this current at negative potentials without inducing any shifts in reversal potential which matched the equilibrium for Cl−(∼0 mV). While NFA produced stimulation in cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP at potentials negative to −20 mV (Figure 3A), the stimulation was only apparent for potentials negative to −50 mV in cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and KN-93 (Figure 3B); in fact NFA blocked ICl(Ca) at potentials between −40 and −10 mV and this led to the appearance of a crossover point at −50 mV (see arrow). Taken together these results suggested that a phosphorylation step might be causing a shift in the voltage dependence of NFA-induced block and stimulation.

Figure 3.

The voltage dependence of ICl(Ca) block by NFA is altered by phosphorylation levels. (A) On the left, two representative families of currents from a cell dialysed with 5 mM ATP, before (upper) and after (lower) a 10 min application of 100 µM NFA. Currents were evoked by stepping in 10 mV increments from HP =−50 mV to 1 s test potentials ranging from −100 mV to +140 mV following a 10 min period of dialysis. On the right, mean current–voltage relationships generated from similar families of currents after 10 min of cell dialysis with 5 mM ATP (n= 10), and after 10 min with the addition of 100 µM NFA to the external solution (n= 10). The inset highlights an expanded segment of the current–voltage relationship from −100 mV to −20 mV. (B) was generated in a similar fashion to (A) except for the fact that in (B), cells were dialysed with a pipette solution containing 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93 (n= 5). Please note in (B) the negative shift in voltage where block is converted to stimulation when phosphorylation is minimized (indicated by the arrow in the inset). *P < 0.05.

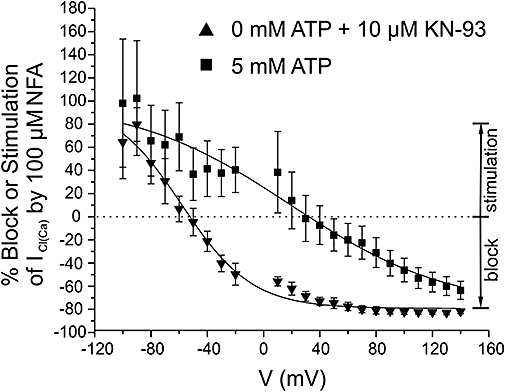

To test this hypothesis, the intensity of block or stimulation (as %) by NFA of steady-state ICl(Ca) was plotted as a function of voltage (Figure 4) and the calculated parameters are presented in Table 1. In Figure 4, the data in 0 mM ATP alone were omitted for the sake of clarity but fell in between those obtained with 5 mM ATP and 0 mM ATP + KN-93 (see Table 1). All data sets could be well fitted by simple Boltzmann relationships. Figure 4 clearly shows that the interaction of NFA with the ClCa channel was voltage-dependent and apparently linked to channel gating (see Discussion). In the absence of ATP, a significant block of ICl(Ca) was apparent above −50 mV and saturated around +50 mV. In contrast, steps more positive than +30 mV were required to detect NFA-induced block of ICl(Ca) with 5 mM ATP. Another interesting feature is the much shallower slope of the relationship obtained with 5 mM versus 0 mM ATP + KN-93 (Figure 4 and Table 1) suggesting a reduced sensitivity to voltage when phosphorylation is promoted. Thus, global phosphorylation has a major impact on the voltage dependence of interaction of the fenamate compound with the channel favouring inhibition over stimulation, both appearing to be functionally linked.

Figure 4.

Altering global phosphorylation status shifts the voltage dependence of the dual effect of NFA on ICl(Ca). The two data sets were obtained after 10 min of cell dialysis with either 5 mM ATP or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93 pipette solutions, before and after addition of 100 µM NFA. % Block was determined at each individual voltage step for each cell using the formula ((INFA/IControl)*100) − 100, where INFA and IControl is the current recorded in the presence and absence of NFA respectively. For IControl, the mean of the first five traces was used in the calculation, while for INFA the mean of the last five stable traces was used. Stimulation appears as a positive value using the above formula and is shown as such. Mean values were then plotted at each voltage, and fitted to a Boltzmann function. Parameters estimated from these fits are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Voltage-dependent parameters describing the interaction of niflumic acid with Ca2+-activated Cl− currents (ICl(Ca)) recorded from pulmonary artery myocytes

| V0.5 (mV) | Slope (mV) | V where y =0 (mV) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 mM ATP | +16.0 ± 2.1 | 59.2 ± 3.9 | 29.7 |

| 0 ATP | −8.9 ± 3.5 | 24.2 ± 3.1 | −3.3 |

| 0 ATP + 10 µM KN-93 | −59.7 ± 0.8 | 26.1 ± 1.5 | −53.7 |

Half-maximal voltage (V0.5) and slope values were estimated by curve fitting of the data plotted in Figure 4 (except for the data with 0 mM ATP alone which was not shown) to a Boltzmann equation. V where y= 0 represents the voltage where the fitted Boltzmann relationships cross the y-axis and corresponds to the voltage at which conversion from block to stimulation by niflumic acid was observed.

Concentration dependence of NFA interaction with ClCa channels altered by phosphorylation

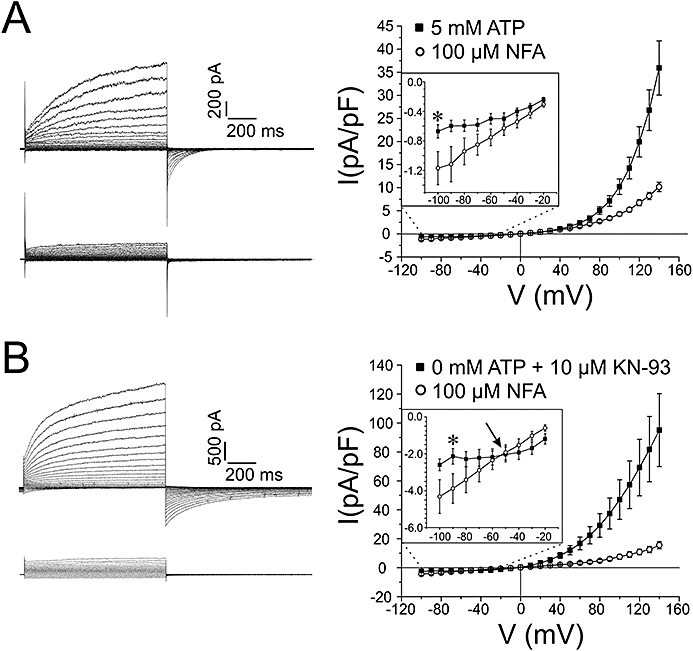

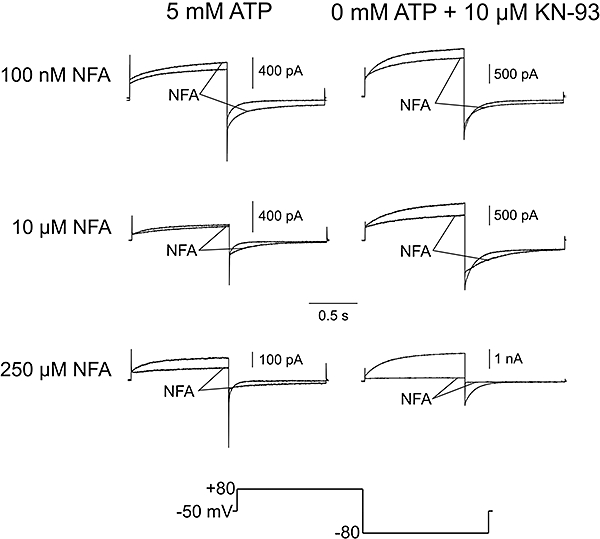

Because of the dual nature of the interaction of NFA with ClCa channels (Piper et al., 2002; Ledoux et al., 2005), we postulated that it might be possible to better distinguish the inhibitory and stimulatory effects of NFA on ICl(Ca) recorded under different states of phosphorylation by examining the effects of a wide range of concentrations (0.1–250 µM) of this compound. Consistent with this possibility, Ledoux et al. (2005) showed that NFA blocked and stimulated ICl(Ca) with different affinities. Figure 5 illustrates the effects of NFA on ICl(Ca) elicited by the standard step protocol described in Figure 1 and depicted at the bottom. Each trace is an average of five traces from four to eight cells recorded immediately prior to, or after a steady-state effect of NFA was observed after 10 min. Interestingly 0.1 mM NFA consistently stimulated the outward current at +80 mV and tail current at −80 mV as well as the steady-state current at the HP in cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP (upper left traces). In contrast, in cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and KN-93, the same concentration of NFA produced inhibition of the outward current at +80 mV, a slight inhibition of the peak inward tail current at −80 mV, and stimulation of steady-state current as evident from the tail current deactivating to a higher negative level (upper right traces). Increasing the concentration of NFA to 10 µM converted the stimulation to block at +80 mV with 5 mM ATP (middle left traces), little effect on peak inward tail current at −80 mV but a profound and well-characterized slowing of deactivation (Hogg et al., 1994; Greenwood and Large, 1996). In the absence of substrate, NFA produced a more potent inhibition of the time-dependent outward current at +80 mV and tail current at −80 mV; as with ATP, NFA markedly slowed deactivation kinetics of ICl(Ca) which crossed over with the control current (middle right traces). Increasing NFA concentration to 250 µM led to more potent block of the current at +80 mV, and now a significant but small inhibition of the peak inward tail current at −80 mV accompanied by the typical slowing of deactivation kinetics at −80 mV with a detectable cross-over with the control current (lower left traces). With 0 mM ATP and KN-93, the same concentration of NFA led to marked block of the outward and inward ICl(Ca) at +80 and −80 mV respectively; it is apparent that the cross-over described above disappeared because of the marked inhibition of the inward tail current.

Figure 5.

Effects of various concentrations of NFA on representative ICl(Ca) traces recorded from cells under different states of global phosphorylation. Average currents are shown before and after application of NFA in cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP, or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93. Current were elicited by 1 s repetitive depolarizing steps from HP =−50 mV to +80 mV, each followed by a 1 s repolarizing step to −80 mV to record tail current. Averaged traces were calculated using Clampfit 9.2 (Molecular Devices). For unmarked control currents, the first five stable traces at the end of 10 min of cell dialysis were averaged for each cell, and subsequently averaged to give a mean current trace for the entire group of cells. Following a 10 min application of NFA, currents (marked ‘NFA’) were similarly averaged. Note the concentration-dependent effect of NFA on deactivation kinetics by comparing the effect of 10 µM NFA on ICl(Ca) in cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP (n= 6), or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93 (n= 3), to the effect of 250 µM NFA on cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP (n= 3), or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93 (n= 3).

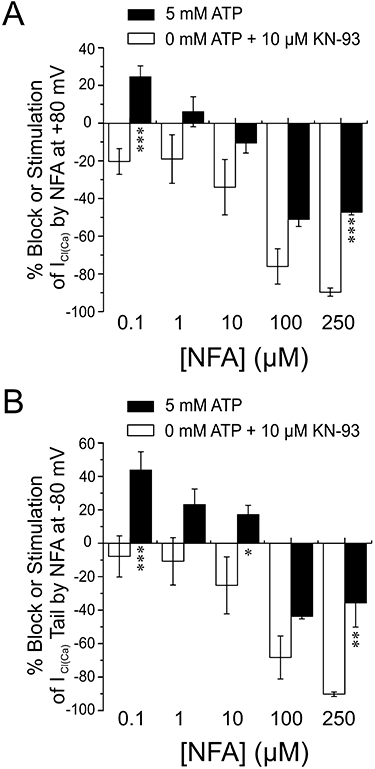

Figure 6 reports mean data for all NFA concentrations tested on ICl(Ca) measured at the end of the step to +80 mV (Figure 6A) and peak inward tail current at −80 mV (Figure 6B). For both graphs, % block or % stimulation is indicated by a negative or positive value respectively. With 0 mM ATP and KN-93, NFA dose-dependently blocked the outward and inward current relaxations with an IC50 of ∼ 46 µM. We were also unable to observe stimulation of ICl(Ca) when testing even lower concentrations of NFA (0.1 µM, n= 3; 1 µM, n= 4; and 10 µM, n= 3). Enabling global phosphorylation with 5 mM ATP led to a significant stimulation of the outward current at +80 mV with 0.1 µM NFA, and inward tail current at −80 mV in the range of 0.1–10 µM NFA. 100 and 250 µM NFA led to significant inhibition of both current components but the magnitude of block was considerably reduced relative to cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and KN-93. Taken together, these results provide convincing evidence for a direct impact of the presumed state of phosphorylation on the ability of NFA to inhibit and stimulate ClCa channels.

Figure 6.

Concentration dependence of the dual effect of NFA on ICl(Ca). (A) In cells dialysed with either 5 mM ATP (filled bars), or 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93, NFA was added for 10 min at concentrations of 0.1, 1, 10, 100 and 250 µM. Current was recorded at the end of 1 s depolarizing pulses to +80 mV from HP of −50 mV, and % block for each cell was calculated by the formula ((INFA/IControl)*100) − 100, where INFA and IControl are the currents recorded in the presence and absence of NFA respectively. For IControl, the mean of the first five traces was used in the calculation, while for INFA the mean of the last five stable traces was used. Stimulation appears as a positive value using the above formula, and is shown as such. Mean calculated values were then determined for each group (5 mM ATP: 0.1 µM NFA, n= 8; 1 µM NFA, n= 5, 10 µM NFA, n= 6; 100 µM NFA, n= 4; 250 µM NFA, n= 4; 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93: 0.1 µM NFA, n= 7; 1 µM NFA, n= 4; 10 µM NFA, n= 3; 100 µM NFA, n= 5; 250 µM NFA, n= 4) and graphed. Panel (B) was generated similarly to (A), but the instantaneous tail current was recorded upon repolarizing the cell to −80 mV for 1 s following the depolarizing step described in (A). Note that while low concentrations of NFA stimulated ICl(Ca) at +80 mV and −80 mV when cells were dialysed with 5 mM ATP, in cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP + 10 µM KN-93 only block by NFA was detected. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 (unpaired Student's t-tests).

Discussion

This study reports for the first time, the effect of a presumed state of phosphorylation in the channel or regulatory subunit, on the interaction of NFA on native Ca2+-activated Cl− currents recorded in freshly isolated rabbit pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. ICl(Ca) elicited by sustained elevated intracellular Ca2+ concentration under conditions favouring either phosphorylation or dephosphorylation led to very marked differences in sensitivity to NFA. NFA produces a paradoxical dual effect on ICl(Ca) in pulmonary artery myocytes, stimulating and blocking the channels at negative and positive potentials respectively (Piper et al., 2002). Analysis of the voltage dependence of interaction of NFA with ICl(Ca) showed that although the maximal level of block at positive potentials and stimulation at negative potentials were similar, promoting global dephosphorylation shifted the voltage at which block was ‘apparently’ converted to stimulation by more than −70 mV. Examination of the concentration dependence of the interaction revealed that a very low concentration of NFA (100 nM) led to stimulation of fully activated ICl(Ca) at +80 mV and tail current at −80 mV in cells dialysed with ATP to support global phosphorylation; stimulation was converted to block between 1 and 10 µM NFA and higher concentrations inhibited the current, albeit to a lower extent than for cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and 10 µM KN-93. In contrast, ICl(Ca) in cells dialysed with 0 mM ATP and KN-93 was blocked in a concentration-dependent manner by NFA in the range of 0.1–250 µM. These results demonstrate that alteration of ClCa channel gating by an unidentified phosphorylation step profoundly influences the mode of interaction of NFA with the channel.

Conditions establishing global states of phosphorylation

Ca2+-activated Cl− channels in airway and arterial myocytes are subject to Ca2+-dependent suppression when intracellular Ca2+ levels are raised and this process involves activation of Ca2+-calmodulin and CaMKII (Wang and Kotlikoff, 1997; Greenwood et al., 2001). Phosphorylation by CaMKII of an unknown target on the channel protein or closely associated accessory regulator protein results in a time-dependent decline of ICl(Ca) that is faster than the Ca2+ transient triggering channel opening (Wang and Kotlikoff, 1997), or current rundown when intracellular Ca2+ levels are clamped above 200 nM (Angermann et al., 2006). It is hypothesized that CaMKII-induced inhibition of ICl(Ca) serves an important role in attenuating the strong depolarizing influence of ClCa channels during excitation (Leblanc et al., 2005). This ‘braking’ or negative feedback regulation by CaMKII is antagonized by calcineurin in rabbit coronary (Ledoux et al., 2003) and pulmonary artery (Greenwood et al., 2004). Several of our present findings – the extensive rundown of ICl(Ca) seen in our study when phosphorylation is supported by 5 mM ATP in the pipette solution, the substantial recovery of the current in myocytes supplied internally with 0 mM ATP with or without KN-93, and the inhibition of the delayed recovery by the calcineurin inhibitor cyclosporine A – are consistent with this hypothesis. These findings are compatible with recent work from our group contrasting the effects of cell dialysis with 3 mM ATP or 3 mM AMP-PNP, a non-hydrolysable analogue of ATP (Angermann et al., 2006). Also in accord with this idea, the higher ATP concentration used in the present study (5 vs. 3 mM in Angermann et al., 2006) enhanced the rate and magnitude of ICl(Ca) rundown. Angermann et al. (2006) proposed a kinetic model whereby phosphorylation induces state-dependent block through voltage-dependent gating steps favouring closure at high levels of Ca2+ occupancy on the cytoplasmic side of the channel. This model predicts more rapid activation at positive potentials and slower deactivation kinetics at negative potentials at high [Ca2+]i when the channel or an unknown regulatory element is dephosphorylated by endogenous phosphatases. Currents elicited in cells supplied with 0 mM ATP and KN-93 to inhibit CaMKII, activated more quickly and deactivated more slowly than those dialysed with 5 mM ATP. Our results thus firmly establish that the underlying pore-forming or regulatory subunit of ClCa channels was either extensively phosphorylated (5 mM ATP) or dephosphorylated (0 mM ATP, with or without KN-93) after 10 min of cell dialysis, prior to any application of drug.

Global phosphorylation attenuates the block of ICl(Ca) by NFA

Our first series of experiments were designed to examine the effects of 100 µM NFA, a widely used concentration, on presumed phosphorylated and dephosphorylated ClCa channels. The rationale for these experiments was based on the observation that NFA preferentially interacts with open ClCa channels and that the block is voltage-dependent (Hogg et al., 1994; Large and Wang, 1996). We thus hypothesized that presumed phosphorylation-induced channel closure might reduce the ability of NFA to block ICl(Ca). Our data confirmed this hypothesis by showing that steady-state block at +90 mV by this compound was significantly greater in cells lacking ATP. Although the maximal levels of achievable inhibition or stimulation were similar, analysis of the voltage dependence of the interaction of NFA with the channels revealed striking differences. For presumed dephosphorylated channels, the block was sharply voltage-dependent below 0 mV and stimulation was apparent below −50 mV. In contrast, stimulation was evident at potentials negative to +20 mV in cells dialysed with 5 mM ATP whereas block was only apparent at potentials more positive than +20 mV. These data suggest that presumed phosphorylation reduces the blocking efficacy of NFA, an effect that may favour the unmasking of the stimulatory effect of NFA. Whether these two opposing effects of NFA are independent as previously suggested by our group for the effects of NFA on ICl(Ca) in rabbit coronary artery myocytes (Ledoux et al., 2003) will require more investigation. One possibility to explain these observations is that the NFA binding site responsible for blocking the channel becomes more easily accessible by channel opening, a situation favoured by presumed dephosphorylation; consistent with this idea was the observation that cell dialysis with 500 nM Ca2+ and 3 mM AMP-PNP caused an elevation of basal ClCa channel conductance between −100 and −50 mV, and increased progressively from −50 to +130 mV (Angermann et al., 2006). This contrasted with ClCa conductance in myocytes dialysed with 5 mM ATP which was very small from −100 to ∼0 mV and increased sharply beyond this voltage. An alternative explanation is that presumed phosphorylation favoured NFA-mediated stimulation that counteracted inhibition.

Pharmacological significance

To our knowledge, there is only one other study demonstrating the impact of altered channel gating because of phosphorylation on the pharmacology of an anion channel. Derand et al. (2003) showed that the activation of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) anion channel by a benzimidazolone, NS004, was influenced by the state of phosphorylation of the R domain by cAMP-dependent protein kinase. This compound was shown to activate phosphorylated CFTR with an EC50 of 11 µM while an EC50 in excess of 100 µM was determined for non-phosphorylated CFTR channels. Derand et al. (2003) suggested that phosphorylation facilitates binding site accessibility through domain interactions or conformational changes. We propose a similar paradigm, albeit in the opposite direction, for the attenuated ability of NFA to inhibit presumed phosphorylated ClCa channels. CaMKII-induced phosphorylation may occlude the binding site by voltage-dependent steric hindrance, or by reduced availability through a state-dependent mechanism.

The present study offers some interesting clues relating to the relatively wide range of IC50 values for NFA to block ICl(Ca) in VSMCs. In the first comprehensive description of the mechanism of block of this current in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells, Hogg et al. (1994) showed that NFA blocked STICs produced by ClCa channels with an IC50 of ∼1–4 µM. 10 µM NFA blocked the slow inward ICl(Ca) tail evoked by Ca2+ entry through L-type Ca2+ channels (ICaL) by 71% in rabbit coronary artery (Lamb et al., 1994), implying an EC50 value below that concentration. In the same preparation, NFA reduced ICl(Ca) elicited by sustained 500 nM Ca2+ with a much higher IC50 (159 µM; Ledoux et al., 2005). One important difference in the methods used to elicit ICl(Ca) is that STICs and ICaL-induced ICl(Ca) are evoked by transient elevations of [Ca2+]i. Autophosphorylation of CaMKII may be quite limited; in fact, the phosphorylation balance is likely to be shifted towards a dephosphorylation state as calcineurin displays about two orders of magnitude higher affinity for Ca2+-CaM than CaMKII and is directly activated by Ca2+ via an interaction with the B subunit of calcineurin (Abraham et al., 1996; Klee et al., 1998; Rusnak and Mertz, 2000; Ledoux et al., 2003). These results suggest caution when using NFA as a pharmacological tool to assess the role of ClCa channels in controlling vascular tone. Large sustained elevations in [Ca2+]i caused by high concentrations of constricting agonists is likely to promote a higher state of phosphorylation of ClCa channels and reduced efficacy of NFA. Indeed, a study by Remillard et al. (2000) showed a progressive attenuation of NFA-induced vasorelaxation of pressurized rabbit mesenteric small arteries when the concentration of the α1-adrenoceptor agonist, phenylephrine, was raised from 100 nM to 10 µM. The recent discoveries of the Bestrophin (Leblanc et al., 2005; Hartzell et al., 2008) and TMEM16A/B genes (Caputo et al., 2008; Schroeder et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2008) as novel molecular candidates for ClCa genes will soon bring novel insight into the mechanisms regulating their activation by Ca2+, voltage and phosphorylation, and how the interplay of these factors influences their pharmacology.

Acknowledgments

We thank Catherine Lachendro, Janice Tinney and Marissa Huebner for their technical support in isolating pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and preparing solutions. This study was supported by a grant to NL from the National Institutes of Health (Grant 5 RO1 HL 075477) and a grant to IAG from the British Heart Foundation (PG/ 05/ 038). The publication was also made possible by a grant to NL (NCRR 5 P20 RR15581) from the National Center for Research Resources, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) supporting two Centers of Biomedical Research Excellence (COBRE) at the University of Nevada School of Medicine, Reno, Nevada. The contents of the manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NCRR or NIH.

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AMP-PNP

adenosine 5′-(β,γ-imido)-triphosphate

- BAPTA

1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- BKCa

large conductance calcium-activated potassium channel

- CaM

calmodulin

- CaMKII

calmodulin-dependent protein kinase type II

- ClCa

calcium-activated chloride channel

- CsA

cyclosporine A

- HP

holding potential

- ICaL

L-type calcium current

- ICl(Ca)

calcium-activated chloride current

- IsK

slow delayed rectifier potassium current

- I-V

current–voltage relationship

- NFA

niflumic acid

- PA

pulmonary artery

- PSS

physiological salt solution

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- STICs

spontaneous transient inward currents

- V0.5

half-maximal voltage

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Abraham ST, Benscoter H, Schworer CM, Singer HA. In situ Ca2+ dependence for activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2506–2513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angermann JE, Sanguinetti AR, Kenyon JL, Leblanc N, Greenwood IA. Mechanism of the inhibition of Ca2+-activated Cl- currents by phosphorylation in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:73–87. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, Pedemonte N, Barsanti C, Sondo E, et al. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–594. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp LH, Turner JL, Kozlowski RZ. Ca2+-activated Cl- currents in pulmonary arterial myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1996;39:H1577, H1584. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1996.270.5.H1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criddle DN, de Moura RS, Greenwood IA, Large WA. Effect of niflumic acid on noradrenaline-induced contractions of the rat aorta. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1065–1071. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criddle DN, de Moura RS, Greenwood IA, Large WA. Inhibitory action of niflumic acid on noradrenaline- and 5-hydroxytryptamine-induced pressor responses in the isolated mesenteric vascular bed of the rat. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;120:813–818. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0700981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derand R, Bulteau-Pignoux L, Becq F. Comparative pharmacology of the activity of wild-type and G551D mutated CFTR chloride channel: effect of the benzimidazolone derivative NS004. J Membr Biol. 2003;194:109–117. doi: 10.1007/s00232-003-2030-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood IA, Large WA. Comparison of the effects of fenamates on Ca-activated chloride and potassium currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;116:2939–2948. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15948.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood IA, Large WA. Analysis of the time course of calcium-activated chloride ‘tail’ currents in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 1996;432:970–979. doi: 10.1007/s004240050224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood IA, Large WA. Properties of a Cl− current activated by cell swelling in rabbit portal vein vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H1524, H1532. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.5.H1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Leblanc N. Differential regulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit arterial and portal vein smooth muscle cells by Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent kinase. J Physiol. 2001;534:395–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00395.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood IA, Ledoux J, Sanguinetti A, Perrino BA, Leblanc N. Calcineurin Aα but not Aβ augments ICl(Ca) in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38830–38837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartzell HC, Qu Z, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT. Molecular physiology of bestrophins: multifunctional membrane proteins linked to best disease and other retinopathies. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:639–672. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00022.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogg RC, Wang Q, Large WA. Action of niflumic acid on evoked and spontaneous calcium-activated chloride and potassium currents in smooth muscle cells from rabbit portal vein. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;112:977–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb13177.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen J, Sims SM. Spontaneous transient inward currents and rhythmicity in canine and guinea-pig tracheal smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch. 1994;427:473–480. doi: 10.1007/BF00374263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee CB, Ren H, Wang XT. Regulation of the calmodulin-stimulated protein phosphatase, calcineurin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13367–13370. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb FS, Barna TJ. Chloride ion currents contribute functionally to norepinephrine-induced vascular contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1998;275:H151, H160. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.1.H151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamb FS, Volk KA, Shibata EF. Calcium-activated chloride current in rabbit coronary artery myocytes. Circ Res. 1994;75:742–750. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large WA, Wang Q. Characteristics and physiological role of the Ca2+-activated Cl− conductance in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1996;271:C435, C454. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.2.C435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N, Leung PM. Indirect stimulation of Ca2+-activated Cl− current by Na+/Ca2+ exchange in rabbit portal vein smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1995;268:H1906, H1917. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.5.H1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc N, Ledoux J, Saleh S, Sanguinetti A, Angermann J, O'Driscoll K, et al. Regulation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle cells: a complex picture is emerging. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2005;83:541–556. doi: 10.1139/y05-040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux J, Greenwood I, Villeneuve LR, Leblanc N. Modulation of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels by calcineurin in rabbit coronary arterial myocytes. J Physiol. 2003;552:701–714. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.043836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledoux J, Greenwood IA, Leblanc N. Dynamics of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channel modulation by niflumic acid in rabbit coronary arterial myocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;67:163–173. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacaud P, Loirand G, Lavie JL, Mironneau C, Mironneau J. Calcium-activated chloride current in rat vascular smooth muscle cells in short-term primary culture. Pflugers Arch. 1989;413:629–636. doi: 10.1007/BF00581813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper AS, Greenwood IA, Large WA. Dual effect of blocking agents on Ca2+-activated Cl− currents in rabbit pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Physiol. 2002;539:119–131. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remillard CV, Lupien MA, Crepeau V, Leblanc N. Role of Ca2+- and swelling-activated Cl− channels in a1-adrenoceptor-mediated tone in pressurized rabbit mesenteric arterioles. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;46:557–568. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusnak F, Mertz P. Calcineurin: Form and function. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:1483–1521. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.4.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BC, Cheng T, Jan YN, Jan LY. Expression cloning of TMEM16A as a calcium-activated chloride channel subunit. Cell. 2008;134:1019–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YX, Kotlikoff MI. Inactivation of calcium-activated chloride channels in smooth muscle by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14918–14923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YD, Cho H, Koo JY, Tak MH, Cho Y, Shim WS, et al. TMEM16A confers receptor-activated calcium-dependent chloride conductance. Nature. 2008;455:1210–1215. doi: 10.1038/nature07313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan XJ. Role of calcium-activated chloride current in regulating pulmonary vasomotor tone. Am J Physiol Lung Respir Physiol. 1997;272:L959, L968. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.5.L959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZhuGe RH, Sims SM, Tuft RA, Fogarty KE, Walsh JV. Ca2+ sparks activate K+ and Cl− channels, resulting in spontaneous transient currents in guinea-pig tracheal myocytes. J Physiol. 1998;513:711–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.711ba.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]