Abstract

Previously, safety and immunogenicity of human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) or 18 E7-pulsed dendritic cells (DC) vaccinations were demonstrated in a dose-escalation Phase I clinical trial which enrolled ten patients diagnosed with stage IB or IIA cervical cancer (nine HPV 16-positive, one HPV 18-positive). The goal of the study was to define the T-cell epitopes of HPV 16 or 18 E7 protein in these patients in order to develop new strategies for treating HPV-associated malignancies. This was accomplished through establishing T-cell lines by stimulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells with autologous mature DC pulsed with the HPV 16 or 18 E7 protein, examining the T-cell responses using ELISPOT assays, and isolating E7-specific T-cell clones based on IFN-γ secretion. Then, the epitope was characterized in terms of its core sequence and the restriction element. Twelve T-cell lines from eight subjects (seven HPV 16-positive, one HPV 18-positive) were evaluated. Positive T-cell responses were demonstrated in four subjects (all HPV 16-positive). All four were positive for the HPV 16 E7 46-70 (EPDRAHYNIVTFCCKCDSTLRLCVQ) region. T-cell clones specific for the E7 47–70 region were isolated from one of the subjects. Further analyses revealed a novel, naturally processed, CD4 T-cell epitope, E7 58–68 (CCKCDSTLRLC), restricted by the HLA-DR17 molecule.

Keywords: Cervical cancer, Human papillomavirus (HPV), Dendritic cells (DC), T-cell epitope

Introduction

Cervical cancer represents the second most common malignant cancer in females worldwide. The close association between high risk human papillomaviruses (HPVs) and the development of cervical cancer is well documented [31, 34]. High risk HPVs, the most commonly human papillomavius type 16 (HPV 16) and HPV 18, encode two viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins. They are constitutively expressed in cervical cancer cells and are required for malignant transformation and the maintenance of malignant phenotype of cervical cancer [33, 34]. Therefore, high risk HPV E6 or E7 oncoprotein may represent an attractive target for immunotherapeutic strategies for cervical cancer.

Identification of T-cell epitopes of HPV E6 or E7 protein may be useful for the development of refined peptide-based immunotherapy for cervical cancer and for evaluation of T-cell responses to antigens after immunotherapy. Three T-cell epitopes of HPV 16 (E7 11–20, E7 82–90, E7 86–93) were identified by analyzing the immunogenicity of the peptides encoded by HPV 16 E6 and E7 in vivo and in vitro [22]. HPV 16 E7 12–20 and E7 86–93 peptide were used to treat 18 patients with HPV 16-positive high-grade cervical or vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia in a vaccine trial [13]. Three subjects showed complete regression and six subjects had partial regression of their cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions. Another HLA-DQB1*02-restricted HPV 16 E7 71–85 epitope was identified from healthy donors, and immune responses to this epitope have been shown to be correlated with spontaneous regression of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions in HPV 16-positive women [21]. The goal of the present study was to characterize the HPV T-cell epitopes recognized in cervical cancer patients who were treated with the full length HPV 16/18 E7 protein-pulsed dendritic cells (DC) vaccines. In this manuscript, a novel HPV 16 E7 CD4 T-cell epitope [E7 58–68 (CCKCDSTLRLC) restricted by the HLA-DR17 molecule], within the most commonly recognized region among these patients, is described.

Material and methods

Subjects and T-cell lines

Ten subjects with stage IB or IIA cervical cancer (nine HPV 16-positive, one HPV 18-positive) in this study were participants of a Phase I escalating dose trial of HPV 16/18 E7 DC vaccine described previously [26]. Five subcutaneous injections of autologous mature DC pulsed with recombinant HPV 16 or 18 E7 protein were administered 21 days apart. The protocol was approved by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences Internal Review Board and the Food and Drug Administration. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant. Seventeen T-cell lines, established by stimulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) with autologous mature DC pulsed with full-length HPV 16 or 18 E7 protein [26], were available from all ten subjects for this study. These PBMC were collected on day 56 after three vaccine administrations (referred to as time 1), on day 98 after five vaccine administrations (time 2), or on day 144 (without any further vaccinations; time 3). The T-cell lines were cryopreserved until 1 day prior to performing IFN-γ ELISPOT assays.

Synthetic HPV 16 or 18 E7 peptides

A set of 15-mer peptides overlapping by the central ten amino acids and a set of 9-mer peptides overlapping by the central eight amino acids for the HPV 16 E7 protein have been described previously [14]. A set of 15-mer peptides (also overlapping by ten amino acids) covering the HPV18 E7 protein were synthesized by CPC Scientific Inc. (San Jose, CA, USA). To define the core sequence of the T-cell epitope from subject 15–04, six 10-mer peptides, overlapping by the central nine amino acids, covering the HPV 16 E7 56–70 region [HPV 16 E7 56–65 (TFCCKCDSTL); HPV 16 E7 57–66 (FCCKCDSTLR); HPV 16 E7 58–67 (CCKCDSTLRL); HPV 16 E7 59–68 (CKCDSTLRLC); HPV 16 E7 60–69 (KCDSTLRLCV); HPV 16 E7 61–70 (CDSTLRLCVQ)], and one 11-mer peptide [HPV 16 E7 58–68 (CCKCDSTLRLC)] were also synthesized (CPC Scientific, Inc.).

Identifying regions that contain potential T-cell epitopes

To identify regions that contain potential T-cell epitopes, an ELISPOT assay was performed utilizing a method previously used to study CD8 T-cell epitopes [16]. In this study, unselected T-cell lines were examined using peptide pools (three 15-mer peptides contained in each pool) covering the HPV 16 or HPV 18 E7 protein depending on the HPV type of the subject’s tumor. Cell recovery was considered adequate when 1 × 105 cells were available per well in duplicates for peptide wells and media wells.

MultiScreen-MAHA 96-wells plate (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) was coated with anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (1-DIK; Mabtech, Stockholm, Sweden; 5 μg/ml) overnight at 4°C. After the wells were washed and were blocked, 1 × 105 cells were added per well along with pools of peptides (10 μM of each) and recombinant human interleukin-2 (rhIL-2) (20 U/ml) in duplicate. Negative control wells contained media only, and positive control wells contained phytohaemagglutin (PHA) (10 μg/ml). Following a 24 h incubation, the wells were washed, and secondary antibody (biotin-conjugated anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody; 7-B6-1, Mabtech) was added (l μg/ml). After 2 h of incubation and washing, avidin-bound biotinylated horseradish peroxidase H (Vectastain Elite Kit; Vector laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) was added. After 1 h of incubation, the wells were washed, and spots were developed using stable diaminobenzene (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL, USA). The spot-forming units were counted using an automated Elispot analyzer (Cell Technology Inc., Jessup, MD, USA). HPV 16/18 E7-specific T-cell responses were considered positive if averaged spot-forming units in peptide-containing wells were at least twice as those in the negative control wells containing media only [12, 16].

Selecting and growing antigen-specific T-cell clones

Using a method previously developed by our group for characterizing HPV-specific CD8 T-cell epitopes, antigen-specific T-cell clones were isolated and characterized [14, 15]. Sufficient cells from the T-cell lines were remaining only for subjects 15-03 and 15-04 to perform this part of the analysis. Briefly, the T-cell lines were stimulated with positive peptide pools (10 μM each), and were positively selected with the use of the IFN-γ Secretion Assay Cell Enrichment and Detection Kit (Miltenyi Biontec Inc., Auburn, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions. Antigen-specific T-cell clones were isolated using a limiting dilution method as described previously [15].

Screening T-cell clones

An ELISPOT assay was used to screen for epitope-specific T-cell clones as previously described [15]. Two 15-mer peptide pools (10 μM each peptide) covering the HPV 16 E7 46–70 region and covering the HPV 16 E7 61–85 region, respectively, were used. The wells that showed spots in an ELISPOT plate with one peptide pool, but not in other plates, were considered to contain T-cell clones possibly with the specificity of interest.

Confirming the specificity of T-cell clones

T-cell clones that were positive in the screening ELISPOT assay were retested again to confirm the specificity using individual 15-mer peptides (10 μM) contained in the positive peptide pool. One thousand T-cell clone cells were added per well in triplicate along with 1 × 105 autologous Epstein-Barr Virus-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell line (LCL) cells and rhIL-2 (20 U/ml). Otherwise, ELISPOT assay was performed as described above.

Determining the mode of antigen presentation

To assess whether the T-cell epitope being studied is processed endogenously through the MHC class I pathway, an ELISPOT assay was performed using the autologous LCL cells (1 × 105 cells per well) infected with previously described recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the E6 protein (E6-vac), E7 protein (E7-vac) or the wild-type virus, Western Reserve (WR), at a multiplicity of infection of five in duplicate along with rhIL-2 (20 U/ml) [17]. One thousand T-clone cells were added to each well. As a positive control, a T-cell clone (27G6), previously demonstrated to recognize HPV 16 E7 79-87 (LEDLLMGTL) endogenously processed CD8 T-cell epitope restricted by the HLA-B60 molecule, was included [14].

Another ELISPOT assay was performed to assess whether the T-cell epitope of interest is processed through the MHC class II pathway using recombinant E7 protein-pulsed autologous mature DC [26]. Two thousand five hundred DC pulsed with recombinant E7 protein were plated per well in duplicate. Peptide (HPV 16 E7 56–70; 10 μM)-pulsed DC were used as a positive control, and DC alone were included as a negative control. One thousand T-clone cells, 5 × 104 autologous LCL cells, and rhIL-2 (20 U/ml) were added to each well.

Characterizing the surface phenotype of the T-cell clones

The T-cell clones were stained with CD4-PE/CD8-FITC cocktail, CD3-FITC/CD16-PE cocktail, and corresponding isotype controls (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA), and were analyzed using Coulter EPICS XL-MLC flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA).

Identifying the core amino acid sequence of the CD4 T-cell epitope

A series of ELISPOT assays were performed to define the core sequence of the novel CD4 T-cell epitope from subject 15–04. All peptides were used at a concentration of 10 μM along with 20 U/ml of rhIL-2. One thousand cells from each T-cell clone along with 5 × 104 or 1 × 105 autologous LCL cells were plated to each well in duplicate or triplicate. ELISPOT assays were performed with a set of 9-mer peptides, overlapping by eight amino acids, covering the HPV 16 E6 56–70 region, and with a set of 10-mer peptides overlapping by nine amino acids covering the same region. An ELISPOT assay was repeated with two 10-mer peptides which demonstrated the most numbers of spot forming units, an 11-mer peptide encompassing these two 10-mers, and three 9-mers contained in the 11-mer peptide. Serial diluted peptides (the two 10-mers and the 11-mer) were also tested in an ELISPOT assay to define the core sequence of the novel CD4 T-cell epitope.

Identifying the restricting HLA class II molecule

Six allogeneic LCL cells sharing one or more class II molecule(s) with the subject being studied (HLA-DR15, -DR17, -DR51, -DR52, -DQ2, -DQ6) were used for the ELISPOT assay (1 × 103 T-clone cells were plated along with 1 × 105 allogeneic LCL cells per well in triplicate). The E7 56–70 (15-mer) peptide (10 μM) and rhIL-2 (20 U/ml) were added. The HLA type shared between the subject and the allogeneic LCL cells with the largest number of spot-forming units was designated to be the restriction element if the results were corroborated with at least two allogeneic LCLs.

HLA typing

HLA typing was performed at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences HLA Laboratory by a serological method or polymerase chain reaction sequence-specific amplification method.

Results

Patterns of T-cell responses to HPV 16 E7 protein in vaccinated subjects

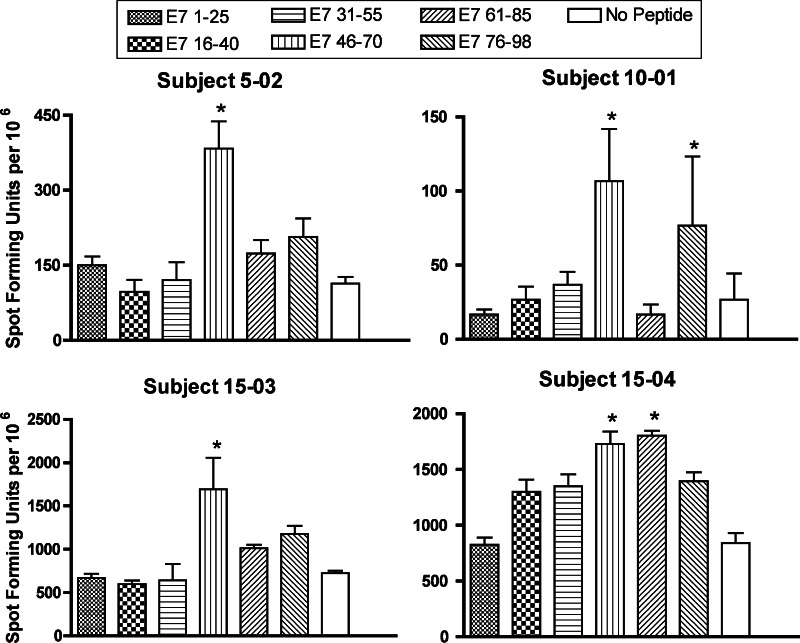

At least one T-cell line from each of the ten subjects (n = 17) was available to be examined, and cell recovery was adequate for twelve T-cell lines from eight subjects [subject 5-02 time 3, subject 5-03 time 2 (HPV 18), subject 10-01 time 2, subject 10-02 times 1 and 2, subject 15-01 times 1 and 2, subject 15-02 times 2 and 3, subject 15-03 times 1 and 2, and subject 15-04 time 2]. Positive responses to at least one region were demonstrated for four T-cell lines from four subjects (5-02, 10-01, 15-03, 15-04) (Fig. 1). All of the four subjects were HPV16 positive, and showed a positive T-cell response to the E7 46-70 region. The subjects 15–04 and 10-01 also showed positive responses to the E7 61-85 region and the E7 76–98 region, respectively.

Fig. 1.

The pattern of T-cell responses to HPV 16 E7 protein in patients with HPV 16 positive cervical cancer treated with DC vaccination. The results for T-cell lines with at least one positive peptide pool are shown (subject 5-02, time 3; subject 10-01, time 2, subject 15-03, time 1; and subject 15-04, time 2). Asterisk positive peptide pool. The bars represent standard errors of the means

Isolation of T-cell clones

The remaining cells of the T-cell line from subjects 15-03 (6.5 × 105 cells) and 15-04 (1.3 × 106 cells) were used to isolate antigen-specific T-cells based on IFN-γ secretion. Approximately 500 or 1,100 IFN-γ secretion cells were isolated from subjects 15-03 or 15-04, respectively. While 599 T-cell clones were isolated from subject 15-04, no T-cell clones grew for subject 15-03.

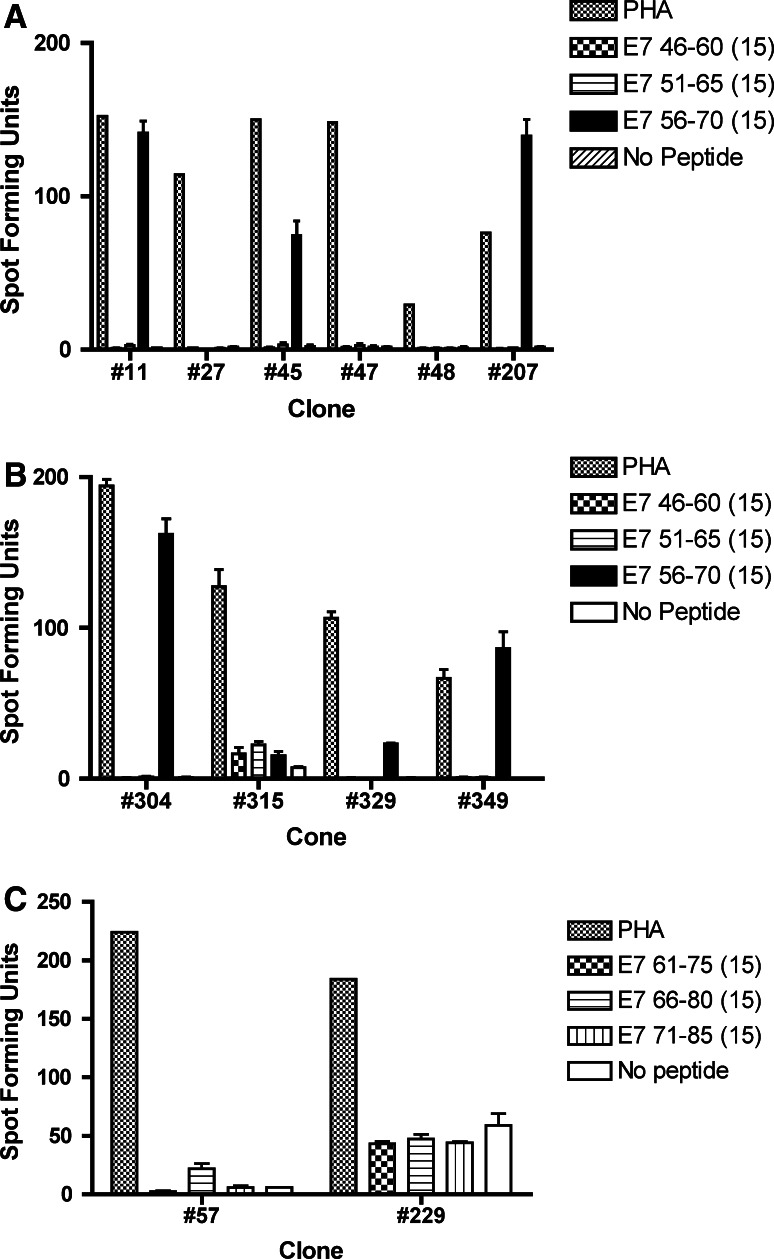

Of a random selection of 376 clones screened, 10 T-cell clones were positive for the E7 46-70 pool, and two clones were positive for the E7 61–85 pool (data not shown). Upon re-testing with individual peptides, six (#11, #45, #207, #304, #329, #349) of ten T-cell clones initially positive for the E7 46–70 pool were positive for the E7 56–70 peptide (Fig. 2a, b). The two T-cell clones initially positive for the E7 61–85 pool turned out to be false-positives (Fig. 2c).

Fig. 2.

ELISPOT assays for determining the specificities of the screen-positive T-cell clones from subject 15-04. The bars represent standard errors of the means. a Three (#11, #45, #207) of six screen-positive T-cell clones showed specificity to E7 56-70. b Three (#304, #329, #349) of four screen-positive T-cell clones showed specificity to E7 56–70. c Two screen-positive T-cell clones in the E7 61–85 region were negative upon re-testing, and were shown to be false-positive

Analyzing the surface phenotype of peptide-specific T-cell clones

Flow cytometric analysis demonstrated that the surface phenotypes of the clones #11, #45, #207, #304, and #329 were CD3+CD4+CD8-CD16– and that of clone #349 was CD3−CD4−CD8+CD16+ (data not shown).

Examining the mode of antigen presentation: MHC Class I versus Class II pathway

To examine the mode of antigen presentation, ELISPOT assays were performed using autologous LCL cells infected with recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the E7 protein and autologous E7 protein-pulsed DC, respectively. None of the T-cell clones (#11, #45, #207, #304, #329) was positive when E6-vac, E7-vac, and WR infected autologous LCL cells while a known HPV 16 E7 CD8 epitope-specific T-cell clone (27G6) was positive (data not shown). On the other hand, all T-cell clones tested (#11, #207, #304) demonstrated IFN-γ secretion when autologous DC pulsed with E7 protein or E7 56–70 15-mer peptide were used (data not shown). These results suggest that the antigen is presented through the MHC class II pathway, but not through the class I pathway.

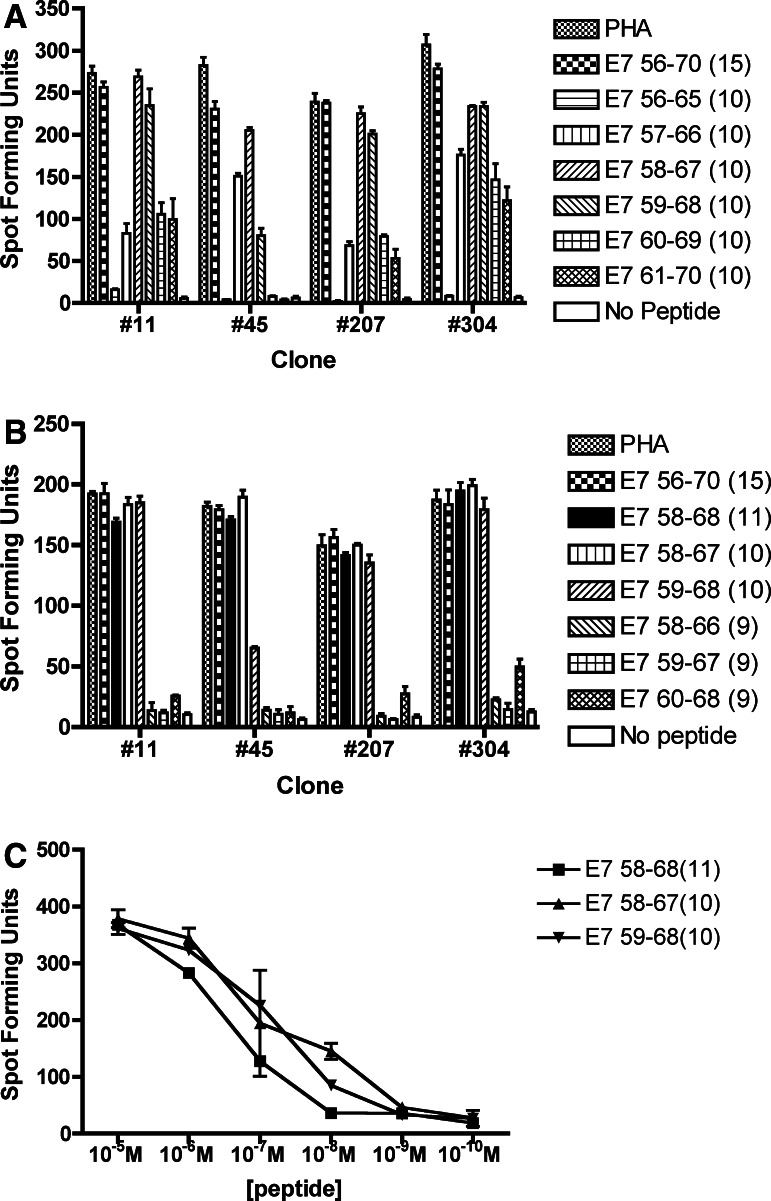

Determining the core sequence of the novel CD4 T-cell epitope

All 9-mer peptides covering the E7 56–70 region were negative (data not shown). Among the six 10-mer peptides examined, the strongest response was seen for the E7 58–67 peptide, followed by the E7 59–68 peptide for three of the four T-cell clones tested (Fig. 3a). Another ELISPOT assay was performed using an 11-mer peptide (E7 58–68) encompassing the two 10-mer peptides with the strongest responses along with E7 56–70 (15-mer), E7 58–67 (10-mer), E7 59–68 (10-mer), E7 58–66 (9-mer), E7 59–67 (9-mer), and E7 60–68 (9-mer) peptides. Equally large numbers of spot-forming units were demonstrated with E7 56–70 (15-mer), E7 58–68 (11-mer), E7 58–67 (10-mer), E7 59–68 (10-mer) (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, serially diluted E7 58–68 (11-mer), E7 58–67 (10-mer), E7 59–68 (10-mer) peptides demonstrated equivalent numbers of spot forming units with all peptides examined (clones #45 and #207 tested) (Fig. 3c). The core sequence of the CD4 T-cell epitope was determined to be HPV 16 E7 58–68.

Fig. 3.

Defining the core sequence of the novel CD4 T-cell epitope within the E7 56–70 region. The core sequence of this novel HPV 16 E7 CD4 epitope appears to be E7 58–68 (11-mer). The bars represent standard errors of the means. a E7 58–67 (10-mer) followed by E7 59–68 (10-mer) showed the highest number of spot-forming units among the six overlapping 10-mer peptides in the E7 56–70 region (#11, #45, and #207). A representative example of two experiments is shown. b E7 56–70 (15-mer), E7 58–68 (11-mer), E7 58–67 (10-mer), and E7 59–68 (10-mer) demonstrated equally high number of spot-forming units but not E7 58–66 (9-mer), E7 59–67 (9-mer), and E7 60–68 (9-mer). c Serially diluted E7 58–68 (11-mer), E7 58–67 (10-mer), and E7 59–68 (10-mer) peptides showed equivalent numbers of spot-forming units. A representative result (#207) of two T-cell clones (#45 and #207) tested is shown

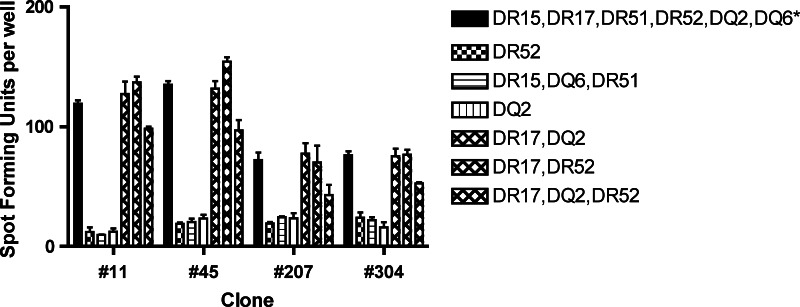

Determining the restricting HLA molecule of the novel CD4 T-cell epitope

The ELISPOT assay demonstrated more spot forming units with the allogeneic LCL cells expressing the HLA-DR17 molecule, but not with LCL cells expressing HLA-DR15, -DQ2, -DQ6, -DR51, or -DR52 (Fig. 4). Therefore, the restriction element was determined to be the HLA–DR17 molecule.

Fig. 4.

An ELISPOT assay for determing the restriction element using allogeneic LCL cells sharing one or more HLA class II molecule with subject 15-04. The results suggest that the restriction element for the novel CD4 T-cell epitope is the HLA-DR 17 molecule. A representative example from three experiments performed is shown. Asterisk autologous LCL cells. The bars represent standard errors of the means

Discussion

The subjects in this study were participants of a Phase I escalating dose trial of HPV 16/18 E7 DC vaccination [26]. They demonstrated increased CD4 responses to the E7 protein, and delayed-type hypersensitivity responses to the E7 antigen and keyhole limpet hemocyanin (a control antigen) after vaccination. We believe that the reason why we were able to demonstrate potential CD4 T-cell epitopes in only four of eight subjects evaluated was at least partly due to negative effects of freezing and thawing cells. Cell recovery was variable from sample to sample. In the future, we plan to perform this analysis immediately after in vitro stimulation to avoid the necessity of freezing and thawing. Another less likely possibility is that the series of 15-mer peptides used may be lacking some epitopes contained in the E7 protein.

CD4 T-cells are important in the development of antitumor responses [9, 20, 25, 27]. It is believed that the effectiveness of these CD4 T-cells lies in their ability to deliver help for priming and maintaining CD8 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte (CTL), which are thought to serve as the dominant effector cells in tumor elimination. The CD4 T-cells do so by providing activation signals to professional antigen presenting cells necessary for priming of tumor-specific CTL [3, 24, 28, 29], and by producing helper T-lymphocyte type 1 cytokines in the proximity of CTL [5]. Moreover, tumor-specific CD4 T-cells may be able to exert their effects on tumors by producing cytokines that can activate eosinophils as well as macrophages [10]. It has been shown that the macrophages have the abilities to kill tumor cells by producing superoxide and nitric oxide [10]. In our Phase I clinical trial, the HPV 16 E7-specific CD4 T-cell responses, but not CD8 T-cell responses, were increased in all vaccine recipients [26]. Taken together, these evidence seem to support the important role of CD4 T-cell activities in anti-tumor activity.

A peptide-based Phase I/II vaccination clinical trial was performed in recurrent or residual cervical cancer patients using two HPV 16 E7-encoded CTL epitopes and one universal helper T-lymphocyte (Th) epitope (PADRE). Though no CTL responses against the HPV 16 E7 peptide were induced, Th-epitope directed proliferative responses were demonstrated in some patients [23]. Induction of tumor-specific CD4 T-cells by vaccination with a specific viral Th epitope was shown to induce protective immunity against MHC class II negative, virus-induced tumor cells [20]. Simultaneous vaccination with the tumor-specific Th and CTL epitopes resulted in strong synergistic protection. Therefore, the optimal vaccines would incorporate tumor specific CTL epitopes and tumor specific Th epitopes to induce activation of both tumor-specific CD8 T-cells and CD4 T-cells.

All four subjects who demonstrated the presence of potential T-cell epitopes in this study showed positive T-cell response to the HPV 16 E7 46–70 region. In addition T-cell clones were isolated from subject 15-04 had specificities only to this region. It is possible that this region may be the immunodominant region in patients who are treated with DC immunotherapy, and more recipients need to be examined to explore this possibility. Identifying an immunodominant region would lead to the development of new strategies for treating HPV-associated malignancies. Furthermore, this region is likely to contain multiple T-cell epitopes given that the HLA types of the four subjects are different (Table 1).

Table 1.

HLA alleles of four subjects from which T-cell lines containing potential T-cell epitopes

| Subject | HLA | |

|---|---|---|

| Class I | Class II | |

| 5-02 | A*2901, A*3301, B*5701, B*3501, Cw*0401 | DRB*1301 (DR13), DRB*1401 (DR14), DRB3*0101 (DR52), DRB3*0202 (DR52), DQB1*0503 (DQ5), DQB1*0603 (DQ6) |

| 10-01 | A*0201, A*0301, B*1501, B*4402, Cw*0304, Cw*0501 | DR4, DR12, DQ3, DRw52, DRw53 |

| 15-03 | A*0201, A*0301, B*0702, B*0801, Cw*0304, Cw*0701 | DRB1*0301 (DR17), DRB1*1501 (DR15), DRB3*0101 (DR52), DRB5*0101 (DR51), DQB1*0201 (DQ2), DQB1*0602 (DQ6) |

| 15-04 | A*0101, A*3201, B*0702, B*0801, Cw*0701, Cw*0702 | DRB1*0301 (DR17), DRB1*1501 (DR15), DRB3*0101 (DR52), DRB5*0101 (DR51), DQB1*0201 (DQ2), DQB1*0602 (DQ6) |

Due to efforts by many investigators [2, 4, 6, 7, 11, 14, 18, 22, 32], numerous CD8 T-cell epitopes of HPV 16 E6 and E7 proteins have been described, and CD8 epitopes relevant to the vast majority of the population are known. On the other hand, only a handful of HPV-specific CD4 T-cell epitopes have been described [i.e., E7 50–62 (33 amino acids long) restricted by DR15, E7 43–77 (35 amino acids long) restricted by DR3, and E7 35–50 (16 amino acids long) restricted by DQ2 described by van der Burg et al. [30]; and E7 61–80 (20 amino acids long) restricted by DR9 described by Okubo et al. [19]. Recently, Gallagher and Man described one HPV 16 E6 CD4 epitope (E6 127–141 restricted by HLA-DRB1*01) and one HPV 18 E6 CD4 epitope (E6 43–57 restricted by HLA-DRB1*15) [8]. In this manuscript, we have described another novel CD4 T-cell epiotpe: HPV 16 E7 58–68 restricted by the HLA-DR17 molecule. To our knowledge, we are the only group that has studied recipients of DC vaccination. The presence of this epitope would not have been predicted by computer alogarithms since it does not contain known binding motifs [1]. Since the DR17 molecule is a split of DR3 molecule, it is a theoretical possibility that the E7 58–68 sequence represent the core sequence of the E7 43–77 (35 amino acid long) epitope described by van der Burg et al. [30]. It would not be possible to exclude this possibility since other investigators did not attempt to characterize the core sequences of the epitopes they described (usually 10 amino acids in length), and 35 amino acids is long enough to contain multiple CD4 T-cell epitopes. Although we designated HPV 16 E7 58–68 (11 amino acids) to be the core sequence, E7 58–67 (10 amino acids) and E7 59–68 (10 amino acids) were equally effective in inducing IFN-γ secretion (Fig. 3c). Further studies are needed to assess whether the E7 46–60 region represents an immunodominant region, and to describe more CD4 T-cell epitopes since they may be used for more targeted immunotherapy in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the subjects for participating in this study. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21CA094507).

Abbreviations

- HPVs

Human papillomaviruses

- HPV 16

Human papillomavius type 16

- DC

Dendritic cells

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- LCL

Epstein-Barr Virus-transformed B-lymphoblastoid cell line

- CTL

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte

- Th

Helper T-lymphocyte

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21CA094507).

An erratum to this article can be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00262-008-0617-z

References

- 1.HIV HLA Anchor Residue Motif Scan

- 2.Alexander M, Salgaller ML, Celis E, Sette A, Barnes WA, Rosenberg SA, Steller MA. Generation of tumor-specific cytolytic T lymphocytes from peripheral blood of cervical cancer patients by in vitro stimulation with a synthetic human papillomavirus type 16 E7 epitope. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1586–1593. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70110-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bennett SR, Carbone FR, Karamalis F, Flavell RA, Miller JF, Heath WR. Help for cytotoxic-T-cell responses is mediated by CD40 signalling. Nature. 1998;393:478–480. doi: 10.1038/30996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bourgault Villada I, Beneton N, Bony C, Connan F, Monsonego J, Bianchi A, Saiag P, Levy JP, Guillet JG, Choppin J. Identification in humans of HPV–16 E6 and E7 protein epitopes recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes in association with HLA-B18 and determination of the HLA-B18-specific binding motif. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:2281–2289. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2000)30:8<2281::AID-IMMU2281>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cassell D, Forman J. Linked recognition of helper and cytotoxic antigenic determinants for the generation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;532:51–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb36325.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evans EM, Man S, Evans AS, Borysiewicz LK. Infiltration of cervical cancer tissue with human papillomavirus-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2943–2950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Evans M, Borysiewicz LK, Evans AS, Rowe M, Jones M, Gileadi U, Cerundolo V, Man S. Antigen processing defects in cervical carcinomas limit the presentation of a CTL epitope from human papillomavirus 16 E6. J Immunol. 2001;167:5420–5428. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.5420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gallagher KM, Man S. Identification of HLA-DR1- and HLA-DR15-restricted human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) and HPV18 E6 epitopes recognized by CD4 + T cells from healthy young women. J Gen Virol. 2007;88:1470–1478. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82558-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Greenberg PD. Adoptive T cell therapy of tumors: mechanisms operative in the recognition and elimination of tumor cells. Adv Immunol. 1991;49:281–355. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)60778-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung K, Hayashi R, Lafond-Walker A, Lowenstein C, Pardoll D, Levitsky H. The central role of CD4(+) T cells in the antitumor immune response. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2357–2368. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.12.2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaufmann AM, Nieland J, Schinz M, Nonn M, Gabelsberger J, Meissner H, Muller RT, Jochmus I, Gissmann L, Schneider A, Durst M. HPV16 L1E7 chimeric virus-like particles induce specific HLA-restricted T cells in humans after in vitro vaccination. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:285–293. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200102)9999:9999<::AID-IJC1181>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaul R, Dong T, Plummer FA, Kimani J, Rostron T, Kiama P, Njagi E, Irungu E, Farah B, Oyugi J, Chakraborty R, MacDonald KS, Bwayo JJ, McMichael A, Rowland-Jones SL. CD8(+) lymphocytes respond to different HIV epitopes in seronegative and infected subjects. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:1303–1310. doi: 10.1172/JCI12433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muderspach L, Wilczynski S, Roman L, Bade L, Felix J, Small LA, Kast WM, Fascio G, Marty V, Weber J. A phase I trial of a human papillomavirus (HPV) peptide vaccine for women with high-grade cervical and vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia who are HPV 16 positive. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:3406–3416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakagawa M, Kim KH, Moscicki A-B. Different Methods of Identifying New Antigenic Epitopes of Human Papillomavirus Type 16 E6 and E7 Proteins. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:889–896. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.5.889-896.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa M, Kim KH, Gillam TM, Moscicki A-B. HLA class I binding promiscuity of the CD8 T-cell epitopes of human papillomavirus type 16 E6 protein. J Virol. 2007;81:1412–1423. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01768-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakagawa M, Kim KH, Moscicki A-B. Patterns of CD8 T-cell epitopes within the human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV 16) E6 protein among young women whose HPV 16 infection has become undetectable. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1003–1005. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.8.1003-1005.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakagawa M, Stites DP, Farhat S, Sisler JR, Moss B, Kong F, Moscicki A-B, Palefsky JM. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to E6 and E7 proteins of human papillomavirus type 16: relationship to cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:927–931. doi: 10.1086/513992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oerke S, Hohn H, Zehbe I, Pilch H, Schicketanz KH, Hitzler WE, Neukirch C, Freitag K, Maeurer MJ. Naturally processed and HLA-B8-presented HPV16 E7 epitope recognized by T cells from patients with cervical cancer. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:766–778. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okubo M, Saito M, Inoku H, Hirata R, Yanagisawa M, Takeda S, Kinoshita K, Maeda H. Analysis of HLA-DRB1*0901-binding HPV–16 E7 helper T cell epitope. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30:120–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2003.00171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ossendorp F, Mengede E, Camps M, Filius R, Melief CJ. Specific T helper cell requirement for optimal induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against major histocompatibility complex class II negative tumors. J Exp Med. 1998;187:693–702. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.5.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Peng S, Trimble C, Wu L, Pardoll D, Roden R, Hung CF, Wu TC. HLA-DQB1*02-restricted HPV–16 E7 peptide-specific CD4 + T-cell immune responses correlate with regression of HPV–16-associated high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:2479–2487. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ressing ME, Sette A, Brandt RM, Ruppert J, Wentworth PA, Hartman M, Oseroff C, Grey HM, Melief CJ, Kast WM. Human CTL epitopes encoded by human papillomavirus type 16 E6 and E7 identified through in vivo and in vitro immunogenicity studies of HLA-A*0201-binding peptides. J Immunol. 1995;154:5934–5943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ressing ME, Driel WJ, Brandt RM, Kenter GG, Jong JH, Bauknecht T, Fleuren GJ, Hoogerhout P, Offringa R, Sette A, Celis E, Grey H, Trimbos BJ, Kast WM, Melief CJ. Detection of T helper responses, but not of human papillomavirus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses, after peptide vaccination of patients with cervical carcinoma. J Immunother. 2000;23:255–266. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200003000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ridge JP, Di Rosa F, Matzinger P. A conditioned dendritic cell can be a temporal bridge between a CD4 + T-helper and a T-killer cell. Nature. 1998;393:474–478. doi: 10.1038/30989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Romerdahl CA, Kripke ML. Role of helper T-lymphocytes in rejection of UV-induced murine skin cancers. Cancer Res. 1988;48:2325–2328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Santin AD, Bellone S, Palmieri M, Zanolini A, Ravaggi A, Siegel ER, Roman JJ, Pecorelli S, Cannon MJ. Human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 E7-pulsed dendritic cell vaccination of stage IB or IIA cervical cancer patients: a phase I escalating-dose trial. J Virol. 2008;82:1968–1979. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02343-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schild HJ, Kyewski B, Von Hoegen P, Schirrmacher V. CD4 + helper T cells are required for resistance to a highly metastatic murine tumor. Eur J Immunol. 1987;17:1863–1866. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830171231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoenberger SP, Toes RE, van der Voort EI, Offringa R, Melief CJ. T-cell help for cytotoxic T lymphocytes is mediated by CD40-CD40L interactions. Nature. 1998;393:480–483. doi: 10.1038/31002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snijders A, Kalinski P, Hilkens CM, Kapsenberg ML. High-level IL-12 production by human dendritic cells requires two signals. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1593–1598. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.11.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Burg SH, Ressing ME, Kwappenberg KM, de Jong A, Straathof K, de Jong J, Geluk A, van Meijgaarden KE, Franken KL, Ottenhoff TH, Fleuren GJ, Kenter G, Melief CJ, Offringa R. Natural T-helper immunity against human papillomavirus type 16 (HPV16) E7-derived peptide epitopes in patients with HPV16-positive cervical lesions: Identification of 3 human leukocyte antigen class II-restricted epitopes. Int J Cancer. 2001;91:612–618. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200002)9999:9999<::AID-IJC1119>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Youde SJ, Dunbar PR, Evans EM, Fiander AN, Borysiewicz LK, Cerundolo V, Man S. Use of fluorogenic histocompatibility leukocyte antigen-A*0201/HPV 16 E7 peptide complexes to isolate rare human cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-recognizing endogenous human papillomavirus antigens. Cancer Res. 2000;60:365–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.zur Hausen H. Immortalization of human cells and their malignant conversion by high risk human papillomavirus genotypes. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:405–411. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1999.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.zur Hausen H. Papillomavirus infections-a major cause of human cancers. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1288:F55–F78. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(96)00020-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]