Abstract

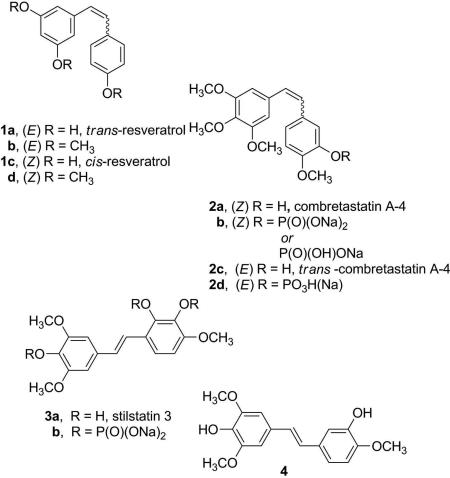

As an extension of our earlier structure/activity investigation of resveratrol (1a) cancer cell growth inhibitory activity compared to the structurally related stilbene combretastatin series (e.g., 2a), an efficient synthesis of E-stilstatin 3 (3a) and its phosphate prodrug 3b was completed. The trans-stilbene 3a was obtained using a convergent synthesis employing a Wittig reaction with phosphonium bromide 9 as the key reaction step. Deprotection of the Z-silyl ether 13 gave E-stilstatin 3 (3a) as the exclusive product. The structure and stereochemistry of 3a was confirmed by X-ray crystal structure determination.

The therapeutic potential of the E-stilbene resveratrol (1a),2a first isolated from roots of Vertarum grandiflorum (white hellebore) in 1940, covers a wide range of diseases as noted in recent reviews.2b,c Stilbene 1a has been reported to be an inhibitor of carcinogenesis at multiple stages via its ability to inhibit cyclooxygenase3a,b and is an anticancer agent with a role in antiangiogenesis2a,4 and in the upregulation of Phase II enzymes, which are involved in detoxifying harmful metabolites and are therefore an indication of chemopreventive activity.2a,5 More recently both in vitro and in vivo studies showed that stilbene 1a induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in tumor cells.6 The cardioprotective effects of resveratrol have been found to include prevention of platelet aggregation in vitro,7 promotion of vasorelaxation,8,9 prevention of LDL oxidation,10 and reduced formation of atherosclerotic plaques and restoration of flow-mediated dilation in rabbits fed on a high-cholesterol diet.11 Resveratrol's (1a) inhibition of cyclooxygenase enzymes3 led to the discovery that along with suppression of the apoptotic neuronal cell death initiated by neuroinflammation typical of Parkinson's disease12a as well as other inflammatory responses,12b specific immune responses were enhanced.13 Resveratrol has been suggested to inhibit tissue death due to oxygen starvation during a heart attack or stroke.14a,b Very importantly, resveratrol's effects on longevity have been of increasing interest.2c,15 In concert with these observations, stilbene 1a and the related Z-stilbene combretastatin A-4 (2a) have been shown to improve fasting blood glucose levels and insulin resistance as summarized below.

An investigation of resveratrol metabolism in humans by Walle16 revealed that 1a was metabolized extensively in the body and that the bulk of an intravenous initial dose was rapidly converted (~ 30 min) to sulfate esters and other derivatives. Furthermore, when the methylated analogue 1b was investigated, it was found to be more active than the natural product in the majority of bioassays.17 Such evidence raised the possibility that one (or more) of its many metabolites is the biologically active agent, rather than resveratrol itself, and has led to a number of investigations focused on the synthesis of new structural modifications of resveratrol (1a),12b,18 including our earlier synthesis and biological study of sodium resverastatin phosphate prodrug19j and stilstatins 1 and 2.1

For over 30 years, we have been exploring the chemistry and the anticancer and other important biological properties of the combretastatins that we isolated from the South African bush willow Combretum caffrum.19 Among the combretastatins, the A-4 (2a, CA4)19a has received major attention owing to its strong inhibition of tubulin polymerization and selective targeting of tumor vascular systems (cancer vascular disrupting), which cuts off the tumor blood flow, leading to hemorrhagic necrosis as well as cancer antiangiogenesis.20 After 10 years of advancing through phase I and II clinical trials, the prodrug sodium combretastatin A-4 phosphate (2b, CA4P) has now entered phase III human cancer clinical trials. In addition, CA4P has advanced to phase II human clinical trials against both myopic and wet macular degeneration (a leading cause of blindness). Current results from the clinical trials have been very encouraging and have stimulated a large number of important SAR20a-c and broad-spectrum biological /medical studies.20a-c, 21, 22

Among the latter investigations are the recent reports that CA4P strongly inhibits gastric tumor metastases by attenuating p-AKT expression (facilitates migration of cancer cells to distant tissue sites)21 and that both CA4 (2a) and resveratrol (1a) activate AMPK (and downregulate gluconeogenic enzyme mRNA levels) in the liver, which improved the fasting blood glucose levels in diabetic db/db mice.22 The AMPK studies with CA4 also showed, as with 1a, that it activates PPAR transcriptional activity, which improved the glucose tolerance in the diabetic mice.22 Overall these results, with AMPK serving as a useful therapeutic target for controlling type 2 diabetes and obesity, suggest another very important avenue for future resveratrol (1a) and CA4 (and CA4P) new drug research.22

Because of the ever increasing biological relationships of certain combretastatins to resveratrol (1a), we have continued our structure/activity investigations 19g,19j,23 and now report the synthesis of a new structural modification of 1a, the polyhydroxylated trans-stilbene designated stilstatin 3 (3a) and its phosphate prodrug (3b). Stilstatin 3 was evaluated first as a cancer cell growth inhibitor, and the data were compared with those of the structurally similar 1a and 1c, methylated derivatives 1b and 1d, combretastatin A4 isomers and salts 2a–d, and the structural modification 4. 23

Results and Discussion

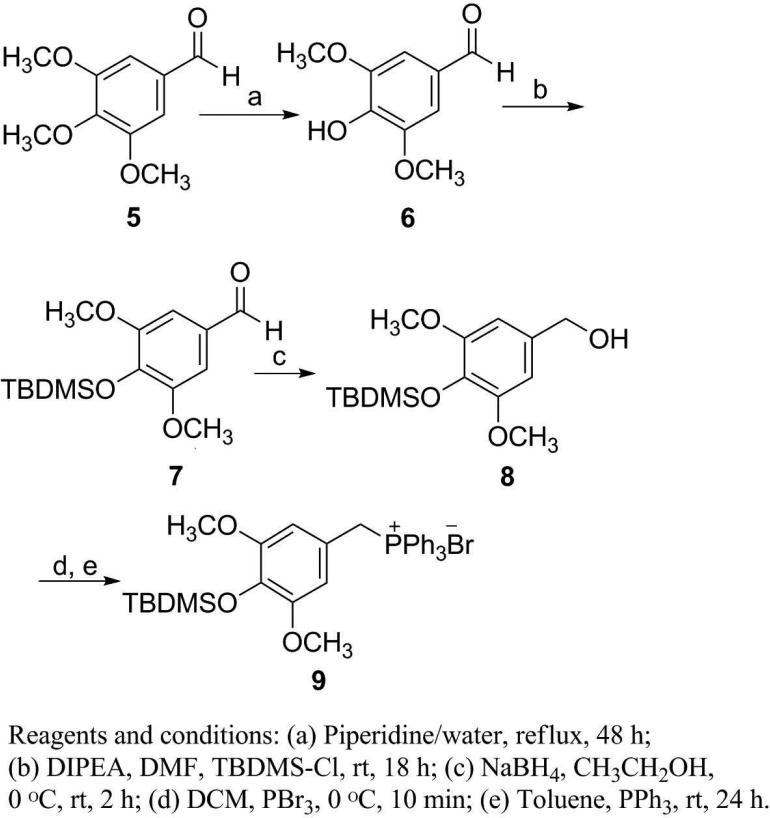

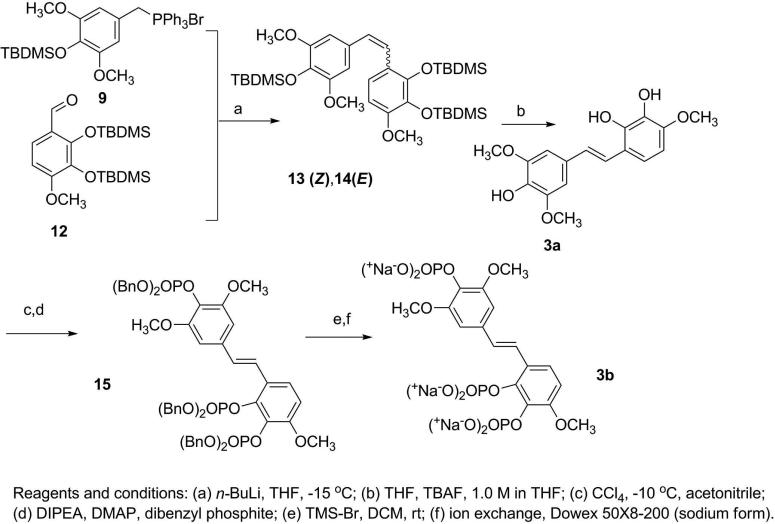

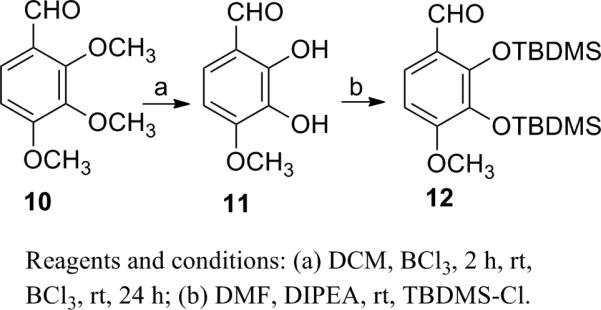

The experimental procedures19 developed for our prior syntheses of combretastatins19i were modified to give E-stilstatin 3. Scheme 1 outlines the synthesis of the necessary phosphonium bromide, where intermediates 6 and 7 were prepared by modifications of prior methods. Silyl ether 7 was reduced to alcohol 8 followed by bromination and phosphorylation to give bromide 9, the A-ring precursor of 3a. Synthesis of the B-ring counterpart was begun as follows (Scheme 2). Commercially available aldehyde 10 was selectively demethylated with BCl3 as previously described19i to furnish diphenol 11. Subsequent protection19d with TBDMSCl gave access to aldehyde 12 in very good overall yields. A Wittig reaction sequence (Scheme 3) employing phosphonium bromide 9 and aldehyde 12 led to stilbene 3a.

Scheme 1.

Scheme 2.

Scheme 3.

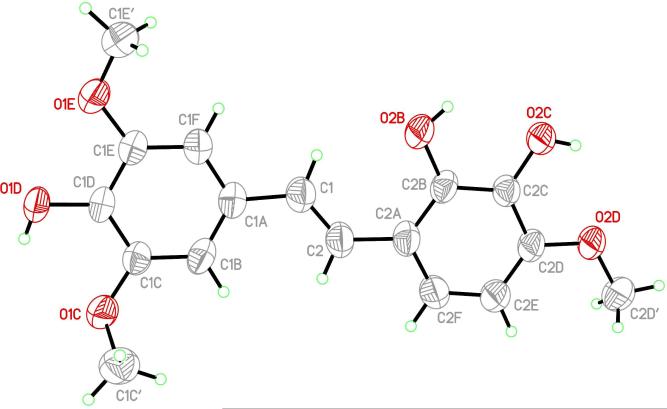

Treatment of 9 with n-butyl lithium at –15 °C afforded the ylide, and addition of aldehyde 12 gave the silyl ethers 13 and 14. The cis/Z-isomer was isolated (by fractional crystallization from ethanol) from the reaction product in 65% yield as a colorless crystalline compound. Further separation of the reaction products (now rich in trans/E) by recrystallization from CH3OH-CH2Cl2 gave the E silyl ether as needles in ~10% yield, confirmed by NMR spectroscopic analysis. A number of attempts at desilylation of Z-isomer 13 using tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF) did not yield the Z product but instead E-stilstatin 3 (3a). We have encountered the geometrical instability of related Z-isomers previously. For example, the Z-isomer of stilbene 423 could be isolated but evaded biological investigations owing to isomerization to the E-stilbene 4 over 1 day (room temperature). E-Stilstatin 3 (3a) recrystallized from benzene-chloroform, and following initial characterization the geometry and overall structure were confirmed by an X-ray crystal structure determination (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

X-ray crystal structure of E-stilstatin 3 (3a).

Photochemical isomerization24 of 3a was also investigated as a route to the Z-isomer, which was needed for biological comparison and evaluation. For the E→Z conversion, Z-stilstatin 3 (3a) in benzene was stirred with benzil and irradiated with a 254 nm UV lamp for 29 h. The products were separated by column chromatography to afford only unreacted E-isomer. Further attempts at photochemical isomerization of the E-isomer in acetonitrile with fluorenone as the sensitizer25 were also unsuccessful. Ultraviolet irradiation was conducted using a standard laboratory UV lamp at 365 nm (and at >280 nm) and also using a medium-pressure UV lamp under an argon atmosphere (photochemical cabinet) with the exclusion of light for 4 h. In the latter experiments, the light pink solution of 3a turned dark orange over time, but examination by NMR did not reveal the Z-isomer as a product in any of these experiments.

Next 3a was phosphorylated with dibenzylphosphite in the presence of CCl419j,26 to give triphosphate 15. The phosphoric acid intermediate was obtained by deprotection of 15 with TMS-Br at rt and was isolated following extraction of the reaction mixture with water. The sodium prodrug was obtained when the aqueous fraction was concentrated to a small volume and eluted through a column containing Dowex 50X8-200 ion exchange resin (sodium form). The UV-active fractions were combined and freeze-dried to yield a cream solid that was reprecipitated from a solution of ethanol-water at 0 °C overnight to yield sodium phosphate 3b as a colorless crystalline powder in quantitative yield.

Stilstatin 3a and its phosphate prodrug (3b) were found to exhibit less cancer cell growth inhibitory activity than resveratrol (1a), resveratrol analogue 1b, and E-stilbene 4 against a panel of human cancer cell lines. Stilstatin 3a showed moderate cytotoxicity (GI50 5.5 μg/ml) against the breast MCF-7 cell line. A comparison of cancer cell line data for the resveratrol synthetic modifications 1b,19j 4,23 and 3a showed a decrease in activity with successive addition of hydroxyl groups to the B-ring of the E-stilbene system. Our previous studies have shown the E-isomer of combretastatin A-419g (2c) to be in some cases 100 times less active in various cancer cell lines than the remarkably potent cis-isomer 2a. These results are consistent with general observations to date that the E-stilbenes are less active as cancer cell growth inhibitors compared to their Z-counterparts. The Z-isomer of resveratrol (1c) was the exception to this general rule and showed slightly less activity than the E-isomer (1a). However the methylated Z-isomer (1d)proved to be more active than its E-isomer (1b). Future investigation of stilstatin 3a and the other resveratrol structural modifications noted herein as sirtuin activators along with the combretastatin series may provide further SAR insights.

Experimental Section

General Experimental Procedures

All solvents and reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI), and Acros Organics (Fischer Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Ether refers to diethyl ether and Ar refers to argon gas. All starting reagents were used as purchased unless otherwise stated. Reactions were monitored by TLC using Analtech silica gel GHLF uniplates visualized under long and short wave UV irradiation along with staining with phosphomolybdic acid/heat, iodine or KMnO4. Solvent extracts were dried over anhydrous magnesium sulfate unless otherwise stated. Where appropriate, the crude products were separated by flash column chromatography on silica gel (230-400 mesh ASTM) from E. Merck. The photochemical experiments were conducted with a standard laboratory UV lamp at 365 nm and 254 nm and with a medium pressure mercury lamp at > 280 nm in a photochemical cabinet under argon.

Melting points are uncorrected and were determined employing an electrothermal 9100 apparatus. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded employing Varian Gemini 300, Varian Unity 400, or Varian Unity 500 instruments using a deuterated solvent and were referenced either to TMS or the solvent. The reported figures are given as ppm. Phosphorus NMR was referenced against a standard of 85% H3PO4. HRMS data were recorded with a Jeol LCmate mass spectrometer and Jeol GCmate. Elemental analyses were determined by Galbraith Laboratories, Inc., Knoxville, TN.

4-Hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (6)

Preparation of compound 6 was repeated as originally described27 from 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzaldehyde (5). Additional NMR and IR data are reported: 74% yield; mp 113-115 °C [lit.27 mp 113-114 °C]; Rf 0.20 in 1:1 hexanes-EtOAc; IR (neat) νmax 3231, 1671, 1607, 1513, 1464, 1330, 1113 cm-1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 3.97 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 6.12 (1H, brs, OH), 7.15 (2H, s, 2 × ArH), 9.82 (1H, s, CHO); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 56.41, 106.65, 128.30, 140.81, 147.31, 190.72; HREIMS m/z 182.0508 (calcd for C9H10O4, 182.0579).

4-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (7)

DIPEA (4.47 g, 34.6 mmol, 6.02 mL) was added to a stirred solution of 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde 6 (4.1 g, 22.47 mmol) and tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (4.06 g, 26.96 mmol) in anhydrous DMF (100 mL). After the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 18 h, water (100 mL) was added and the reaction mixture extracted with EtOAc (3 × 100 mL). The combined organic phase was washed with water (2 × 50 mL) and dried, and the solvent was removed in vacuo. Separation was achieved by column chromatography, eluting with 1:1 hexanes-EtOAc, to give the title compound in quantitative yield (6.65 g) as an off-white solid: mp 78-79 °C; [lit.28 mp 69-71 °C] Rf 0.50 in 1:1 EtOAc-hexanes; IR (neat) νmax 2932, 1690, 1503, 1331, 1126 cm-1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 0.08 (6H,s, (CH3)2Si), 0.93 (9H, s, tBu), 3.77 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 7.01 (2H, s, 2 × ArH), 9.72 (1H, s, CHO); 13C NMR(CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ –4.63, 18.68, 25.58, 55.66, 106.59, 129.28, 140.53, 151.86, 190.88; HRMS APCI+ m/z 297.1519 [M+H]+ (calcd for C15H25O4Si, 297.1522).

4-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-3,5-dimethoxybenzyl alcohol (8)

A solution of benzaldehyde 7 (6.65 g, 22.47 mmol) in ethanol (30 mL) was stirred for 10 min at 0 °C. NaBH4 (1.1 g, 29.21 mmol) was added, and the reaction mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 3 h. Solid NaHCO3 was added until effervescing stopped. The solution was filtered and the solvent removed in vacuo. Separation was realized by filtration through a 2-inch silica gel plug, eluting with 1:1 hexanes-EtOAc, to give the alcohol as a colorless solid in 83% (5.54 g) yield: mp 117-118 °C; Rf 0.24 in 7:3 hexanes-EtOAc; IR (neat) νmax 3295, 2932, 2858, 1591, 1511, 1245, 1134, 906 cm-1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 0.00 (6H, s, (CH3)2Si), 0.89 (9H, s, tBu), 1.80 (1H, brs, OH), 3.67 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 4.46 (2H, s, CH2OH), 6.42 (2H, s, 2 × ArH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ –4.66, 25.79, 55.73, 65.80, 104.10, 133.37, 151.68; HRMS APCI+ m/z 281.1574 [M + H – H2O]+ (calcd for C15H25O3Si, 281.1573).

4-(tert-Butyldimethylsilyloxy)-3,5-dimethoxybenzyltriphenylphosphonium bromide (9)

To a cooled (0 °C) and stirred solution of alcohol 8 (5.54 g, 18.6 mmol) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (50 mL) was added a solution of PBr3 (6.04 g, 22.32 mmol, 2.10 mL) in anhydrous CH2Cl2 (25 mL) dropwise at 0 °C. After stirring at 0 °C for 10 min, the reaction mixture was poured onto ice-cold saturated NaHCO3 solution (100 mL). The separated organic phase was washed with water (20 mL) and dried, and the solvent was removed in vacuo to furnish the bromide intermediate. The oily residue was dissolved in toluene (70 mL), and a solution of PPh3 (4.87 g, 18.6 mmol) in toluene (20 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 10 min. Toluene (~50 mL) was removed in vacuo, and the reaction mixture was allowed to cool over 24 h. The white precipitate was collected by filtration and recrystallized from ethanol to afford the phosphonium salt in 68% yield (7.89 g) as a colorless solid: mp 246-248 °C; Rf 0.50 in 1:9 CH3OH-CH2Cl2; IR (neat) νmax 3050, 2950, 1511, 1463, 1438, 1338, 1249, 1125 cm-1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 0.00 (6H, s, (CH3)2Si), 0.89 (9H, s, tBu), 3.37 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 5.24 (2H, d, J = 13.8 Hz, CH2P), 6.30 (2H, d, J = 2.4 Hz, 2 × ArH), 7.53-7.68 (15H, m, 3 × Ph); 31P NMR (CDCl3, 162 MHz) δ 24.06; HRMS-APCI+ m/z 543.2513 [M–Br]+ (calcd for C33H40O3PSi, 543.2484).

2,3-Dihydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (11)

Preparation of compound 11 was repeated as originally described19i from 2,3,4-trimethoxybenzaldehyde (10). Colorless solid, 87% yield: mp 115-116 °C [lit.19i mp 115-116 °C]; Rf 0.22 in 1:1 hexanes-EtOAc; IR (neat) νmax 3365, 2944, 1645, 1507, 1453, 1277, 1104, 1025 cm-1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 3.97 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.62 (1H, d, J = 14.5 Hz, ArH), 7.12 (1H, d, J = 13.5 Hz, ArH), 9.74 (1H, s, CHO); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 56.58, 103.86, 116.32, 126.28, 133.25, 149.29, 153.23, 195.38; HRMS-APCI+ m/z 169.0554 [M+H]+ (calcd for C8H9O4, 169.0500).

2,3-Bis(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (12)

Preparation of compound 12 was repeated as originally described19c from benzaldehyde 11. Additional 13C NMR data are provided here. Colorless solid, 84% yield: mp 75-76 °C [lit.19c mp 74.5-76 °C]; Rf 0.76 in 1:1 hexanes-EtOAc; IR (neat) νmax 2932, 2859, 1683, 1585, 1455, 1297, 1099 cm-1; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 0.00 (12H, s, 2 × (CH3)2Si), 0.85 (9H, s, tBu), 0.89 (9H, s, tBu), 3.70 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.49 (1H, d, J = 14.5 Hz, ArH), 7.36 (1H, d, J = 15.0 Hz, ArH), 10.08 (1H, s, CHO); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ –3.92, –3.84, 18.55, 18.74, 26.02, 26.17, 55.17, 105.40, 115.21, 120.75, 121.37, 123.36, 136.80, 150.99, 157.53, 189.26; HRMS APCI+ m/z 397.2234 [M +H]+ (calcd for C20H37O4Si2, 397.2230).

2′,3′,4-Tris(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)-3,4′,5-trimethoxy-4-Z- and -E-stilbenes (13,14)

n-Butyllithium (13.7 mmol, 5.5 mL, 2.5 M solution in hexane) was added (dropwise) to a stirred and cooled (–20 °C) suspension of triphenylphosphonium bromide 9 (6.2 g, 9.95 mmol) in anhydrous THF (200 mL). The red reaction solution was stirred for 15 min at –15 °C, before addition of benzaldehyde 12 (4.0 g, 10.1 mmol). Stirring was continued at –15 °C for the duration of the experiment. TLC analysis (49:1 hexanes-EtOAc) showed complete conversion to product after 1 h, and the reaction was terminated with the addition of iced water. The reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc (300 mL), the organic layer was washed with water (100 mL) and dried, and the solvent was removed (in vacuo) to yield a yellow residue. The crude product in ethanol (50 mL) was sonicated to effect solution. The resulting white precipitate was collected and dried to yield a colorless crystalline powder (3.58 g). The ethanol mother liquor was cooled in an ice bath to yield crystals (0.72 g) that had the same Rf value by TLC (95:5 hexanes-EtOAc) as the precipitate. Upon examination by 1H NMR, both precipitate and crystals were found to be the Z-stilstatin 3 derivative 13 and were combined to give 65% overall yield (4.3 g) of 13. The remaining mother liquor was concentrated to a yellow oil which was dissolved in CH3OH and cooled to provide crystals (0.77 g). Examination by 1H NMR showed this product to be a mixture of Z/E isomers (13/14, 0.77 g) in a ratio of 1:3 respectively. Recrystallization of this mixture (0.1 g) from CH2Cl2-CH3OH gave the E-stilbene 14 derivative as needles (0.074 g).

Z-13: mp 110-111 °C, Rf 0.73 in 95:5 hexanes-EtOAc; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 0.08 (6H, s, 2 × (CH3)2Si), 0.102 (6H, s, 2 × (CH3)2Si), 0.171 (6H, s, 2 × (CH3)2Si), 0.980 (18H, s, 2 × (t Bu)), 1.01 (9H, s, tBu), 3.59 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 3.708 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.29 (1H, d, J = 8.7 Hz, H-5’), 6.34 (1H, d, J = 12.3 Hz, -CH=CH-), 6.56 (2H, s, H-2, H-6), 6.87 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-6’); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ –4.40, –3.7, –3.0, 18.8, 19.0, 26.0, 26.4, 26.6, 55.2, 55.8, 104.3, 106.3, 122.5, 123.7, 126.5, 128.3, 130.1, 133.6, 137.0, 146.4, 151.3, 151.7; HRMS-APCI m/z 661.3750 [M+H]+ (calcd for C35H61O6Si3, 661.3776); anal. C 63.96%, H 9.24%, calcd for C35H60O6Si3, C 63.59% H 9.15%.

E-14: mp 118-119 °C, Rf 0.54 in 95:5 hexanes-EtOAc; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 500MHz) δ 0.11 (6H, s, 2 × (CH3)2Si), 0.13 (6H, s, 2 × (CH3)2Si), 0.14 (6H, s, 2 × (CH3)2Si), 0.99 (9H, s, tBu), 1.02 (9H, s, tBu), 1.08 (9H, s, tBu), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.81 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 6.54 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H-5’), 6.68 (2H, s, H-2, H-6), 6.78 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, -CH=CH-), 7.18 (1H, d, J = 8.5 Hz, H-6’), 7.24 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, -CH=CH-); HRMS-APCI+ m/z 661.3782 [M+H]+ (calcd for C35H61O6Si3, 661.3776); anal. C 63.52%, H 9.18%, calcd for C35H60O6Si3, C 63.59% H 9.15%.

E-Stilstatin 3 (3a)

To a cooled (–10 °C) solution of 2′,3′,4-tris(tert-butyldimethylsilyloxy)-3,4′,5-trimethoxy-Z-stilstatin 3 (13, 6.1g, 9.23 mmol) in anhydrous THF (30 mL), was added TBAF (11.1 mmol, 11 mL, 1.0 M solution in THF). The reaction mixture was stirred at –10 °C for 50 min. Ice-cold 6 N HCL (2 mL) was added, and the mixture was extracted with EtOAc (4 × 50 mL). The organic phase was dried and the solvent removed in vacuo to afford a brown oil (3.8 g). Purification was realized by column chromatography (eluting with 1:1 hexanes-EtOAc), leading to a pink crystalline powder (1.2 g) that was recrystallized from benzene-chloroform to yield 3a as colorless crystals: mp 110-111 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300 MHz) δ 3.88 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.91 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 5.39 (1H, s, OH), 5.51(1H, s, OH), 5.61(1H, s, OH), 6.47(d, J = 3 Hz, H-5’), 6.73 (2H, s, H-2, H-6), 7.04-6.98 (2H, m, -CH=CH-, H-6’), 7.15 (1H, d, J = 15.9 Hz, CH=CH); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 56.2, 56.3(2C), 103.1, 103.2, 117.5, 118.6, 121.4, 128.1, 128.3(2C), 129.8, 132.3, 134.4, 141.9, 146.1, 147.2; anal. C 68.93%, H 6.11%, calcd for C17H18O6.C6H6, C 69.64%, H 6.05%.

X-ray Crystal Structure of 3a

(a) Data Collection

A small amber crystal block (0.22 mm × 0.19 mm × 0.18 mm) of 3a grown from a benzene-chloroform solution was mounted on the end of a thin glass fiber using Apiezon type N grease and optically centered. Cell parameter measurements and data collection were performed at ambient temperature (298 ± 1 K) with a Bruker SMART APEX diffractometer using Mo Kα (0.71073 Å) radiation. A sphere of reciprocal space was collected using the Multi-Run scheme available in the Bruker SMART29 data collection package. Three sets of frames were obtained, with each set using 0.30°/frame steps to cover 182° in ω at fixed φ values of 0°, 120°, and 240°, respectively. Data were integrated and reduced using Bruker SAINT,29 resulting in 100% coverage of all unique reflections to a resolution of 0.84 Å with an average redundancy of 4.51.

(b) Crystal data

C17H18O6·(C6H6)1.5, FW = 435.48, monoclinic, P21/c, a = 6.839(2) Å, b = 16.920(5) Å, c = 19.998(6) Å, β = 94.559(6)°, V = 2306.8(12) Å3, Z = 4, ρc = 1.254 Mg m-3, μ(Mo Kα) = 0.089 mm-1, λ = 0.71073 Å, F(000) = 924.

(c) Structure Solution and Refinement

A total of 18,374 reflections was measured, of which 4,068 were independent (Rint = 0.0296) and 2,864 were considered observed (Iobs > 2σ(I)). Final unit cell parameters were determined by least-squares fit of 6,237 reflections covering the resolution range of 8.601 Å to 0.773 Å. An absorption correction was applied using SADABS29 on the full data set. Statistical analysis with the XPREP program in SHELXTL29 indicated that the space group was P21/c. Routine direct methods structure solution was performed with SHELXTL, which produced all non-hydrogen atom coordinates on the single 3a molecule in the asymmetric unit. Upon initial refinement with SHELXTL, the remaining solvent in the asymmetric unit became easily discernible in the Fourier difference map. After full isotropic refinement, the thermal parameters for all non-hydrogen atoms were then allowed to refine anisotropically. Subsequently, hydrogen atoms were added at idealized positions and bond distances with their isotropic thermal parameters fixed at 1.5 times the Uiso values of their bonding partners for the methyl and hydroxyl hydrogens and at 1.2 times the Uiso values of their bonding partners for all others. The model was then allowed to refine with hydrogens constrained as atoms riding on their bonding partners. This resulted in a final standard residual R1 value of 0.0528 for observed data and 0.0731 for all data. Goodness of Fit on F2 was 1.022 and the weighted residual on F2, wR2, was 0.1432 for observed data and 0.1614 for all data. The final Fourier difference map showed minimal electron density, with the largest difference peak and hole having values of 0.218 electrons Å–3 and –0.165 electrons Å–3, respectively. Final bond distances and angles were all within expected and acceptable limits for the 3a molecule. However, the average phenyl C-C distance in the included solvent (1.35 Å) was shorter than typical values (1.39 Å), probably due to the large thermal motion.30

2′,3′,4-O-Tri[bis(benzyl)phosphoryl]- 3,4′,5-trimethoxy-E-stilbene (15)

A solution of E-stilstatin 3 (3a, 1.5 g, 4.7 mmol) in CCl3 (7.5 mL) and acetonitrile (8 mL) was cooled to –10oC. DIPEA (6 mL) and DMAP (0.19 g) were added, and the solution was stirred for several min prior to addition of dibenzylphosphite (6.4 g). After 1 h the reaction had not gone to completion (by TLC), and an additional 5 mL of dibenzylphosphite was added to the brown solution. The reaction mixture was stirred at rt for a further 60 min. Next, KH2PO4 (0.5 M, 200 mL) was added and the mixture stirred for 10 min before extraction with ethyl acetate (3 × 100 mL). The solution was dried (MgSO4) and the solvent removed in vacuo to yield a brown oil. Column chromatography (99:1 CH2Cl2-CH3OH) provided the desired product as a yellow oil (1.29 g, 24.9% yield): Rf 0.25 (3:7 hexanes-EtOAc); 1H NMR (CDCl3, 300MHz) δ 3.66 (6H, s, 2 × OCH3), 3.79 (3H, s, OCH3), 5.02 (4H, m, 2 × CH2Ph), 5.18-5.27 (8H, m, CH2Ph), 6.64 (2H, s, Ar-H-2,6), 6.80-6.88 (m, 2H, -CH=CH-), 7.12-7.14 (32 H, m, 6 × Ph, 2 × Ar-H); 13C NMR (CDCl3, 125 MHz) δ 55.9 (2C), 56.4, 69.5 (2C), 69.8 (2C), 70.1, 70.2, 103.4 (2C), 109.9, 122.3, 122.6, 127.7-128.9, 134.8, 135.4, 135.5, 135.9, 136.0, 136.3, 151.8, 151.9, 152.0.

Sodium Stilstatin 3: 2′,3′,4-O-Triphosphate Prodrug (3b)

To a solution of benzyl phosphate 15 (4.5 g, 4.0 mmol) in anhydrous dichloromethane (150 mL) was added bromotrimethylsilane (3.2 mL, 3.7 g, 24 mmol, 6 equiv) (dropwise), and the reaction mixture stirred at rt for 30 min. The reaction was terminated with the addition of water (100 mL). The phosphoric acid intermediate was not soluble in the organic phase and was immediately converted to the sodium salt by separation and concentration of the aqueous fraction to 30 mL and elution through an ion-exchange column containing Dowex -50W resin (sodium form). The fractions containing the salt were spotted onto TLC plates, and the product-containing fractions were visualized using both UV and I2 vapor. The pooled fractions were reduced to dryness via freeze drying for 24 h to yield a cream solid, which was recrystallized from water-ethanol (ice bath at 0 °C) to yield an off-white powder that was collected and dried (2.7g, 96%): mp 220 °C (chars); 1H NMR (D2O, 400 MHz) δ 3.82 (m, 9H, 3 × OCH3), 6.84 (1 H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, Ar-H), 6.9 (2H, s, Ar-H), 7.0 (1H, d, J = 16.5 Hz, -CH=CH-), 7.4-7.44 (3H, m, Ar-H, -CH=CH-); 13C NMR (D2O, 100 MHz) δ 56.5, 104.1, 109.0, 120.8, 123.4, 127.7, 130.2, 130.3, 134.6, 134.9, 135.0, 144.0, 152.2, 152.3, 152.4.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Human Cancer Cell Growth Inhibition Results (GI50, μg/mL)

| cell line |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| structure | pancreas BXPC-3 | breast MCF-7 | CNS SF-268 | lung-NSC NCI-H460 | colon KM20L2 | prostate DU-145 |

| 1a19j | 3.3 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 3.6 | 13.1 | 3.5 |

| 1b19j | 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 1.5 | ||

| 1c19j | 15.5 | 14.8 | 5.0 | 13.2 | 22.0 | 10.2 |

| 1d19j | 0.0034 | 0.0044 | 0.0028 | 0.0054 | ||

| 2a19j | 0.39 | >0.01 | 0.00060 | 0.34 | 0.00080 | |

| 2c19g | 3.9 | 0.038 | 0.037 | |||

| 3a | >10 | 5.5 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| 3b | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 | >10 |

| 423 | 5.0 | 4.9 | 6.3 | |||

Acknowledgment

We are pleased to acknowledge the very necessary financial support provided by grants RO1 CA 90441-02-05, 2R56-CA 09441-06A1, and 5RO1 CA 090441-07 from the Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, NCI, DHHS; The Arizona Biomedical Research Commission; Dr. Alec D. Keith; J. W. Kieckhefer Foundation; Margaret T. Morris Foundation; the Robert B. Dalton Endowment Fund; and Dr. William Crisp and Mrs. Anita Crisp. For other helpful assistance we thank Drs. J.-C. Chapuis, F. Hogan, M. Hoard, and D. Doubek, as well as M. Dodson.

Footnotes

Dedicated to the memory of Professor Georgy B. Elyakov (1929-2005) for his pioneering contributions to the chemistry and biology of natural products.

Supporting Information Available: X-ray data for E-stilstatin 3 (3a). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References and Notes

- 1.Part 579 in the Antineoplastic Agents series. For part 578, refer to: Pettit GR, Thornhill A, Melody N, Knight JC. J. Nat. Prod. 2009;72:380–388. doi: 10.1021/np800608c.

- 2.a Takaoka MJ. J. Fac. Sci. Hokkaido Imp. Univ. 1940;3:1–16. [Google Scholar]; b Gescher AJ. Planta Med. 2008;74:1651–1655. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1074516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Orallo F. Curr. Med. Chem. 2008;15:1887–1898. doi: 10.2174/092986708785132951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Saiko P, Szakmary A, Jaeger W, Szekeres T. Mutation Res. 2008;658:68–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Baur JA, Sinclair DA. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:493–506. doi: 10.1038/nrd2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Handler N, Brunhofer G, Studenik C, Leisser K, Jaeger W, Parth S, Erker T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:6109–6118. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, Slowing KV, Thomas CF, Beecher CWW, Fong HHS, Farnsworth NR, Kinghorn AD, Mehta RG, Moon RC, Pezzuto JM. Science. 1997;275:218–220. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5297.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tseng SH, Lin SM, Chen JC, Su YH, Huang HY, Chen CK, Lin YP, Chen Y. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:2190–2202. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebbar V, Shen G, Hu R, Kim BR, Chen C, Korytko PJ, Crowell JA, Levine BS, Kong A-NT. Life Sci. 2005;76:2299–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garvin S, Öllinger K, Dabrosin C. Cancer Lett. 2006;231:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Z, Huang Y, Zou J, Cao K, Xu Y, Wu JM. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2002;9:77–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naderali EK, Doyle PJ, Williams G. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 2000;98:537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz M, Luksha L, Logman H, Poston L, Agewall S, Kublickiene K. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2006;290:H1969–H1975. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01065.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frankel EN, Waterhouse AL, Kinsella JE. Lancet. 1993;341:1103–1104. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Z, Zou J, Cao K, Hsieh TC, Huang Y, Wu JM. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2005;16:533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Bureau G, Longpré F, Martinoli M-G. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:403–410. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chen G, Shan W, Wu YL, Ren LX, Dong IH, Ji ZZ. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2005;53:1587–1590. doi: 10.1248/cpb.53.1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu SL, Yu L, Meng KW, Ma ZH, Pan CE. World J. Gastroenterol. 2005;11:4745–4749. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i30.4745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a Hung LM, Su MJ, Chu WK, Chiao CW, Chan WF, Chen JK. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;135:1627–1633. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hung LM, Chen JK, Huang SS, Lee RS, Su MJ. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000;47:549–555. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00102-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Nature. 2004;430:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature02789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang LL, Scherer B, Sinclair DA. Nature. 2003;425:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walle T, Hsieh F, DeLegge MH, Oatis JE, Jr., Walle UK. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2004;32:1377–1382. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cardile V, Chillemi R, Lombardo L, Sciuto S, Spatafora C, Tringali C. J. Biosci. 2007;62:189–195. doi: 10.1515/znc-2007-3-406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murias M, Jäger W, Handler N, Erker T, Horvath Z, Szekeres T, Nohl H, Gille L. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;69:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.a Pettit GR, Cragg GM, Herald DL, Schmidt JM, Lohavanijaya P. Can. J. Chem. 1982;60:1374–1376. [Google Scholar]; b Pettit GR, Singh SB, Cragg GM. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:3404–3406. [Google Scholar]; c Pettit GR, Singh SB, Niven ML, Hamel E, Schmidt JM. J. Nat. Prod. 1987;50:119–131. doi: 10.1021/np50049a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Pettit GR, Singh SB. Can. J. Chem. 1987;65:2390–2396. [Google Scholar]; e Pettit GR, Singh SB, Hamel E, Lin CM, Alberts DS, Garcia-Kendall D. Experientia. 1989;45:209–211. doi: 10.1007/BF01954881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Pettit GR, Singh SB, Boyd MR, Hamel E, Pettit RK, Schmidt JM, Hogan F. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1666–1672. doi: 10.1021/jm00010a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Pettit GR, Rhodes MR, Herald DL, Chaplin DJ, Oliva D. Anticancer Res. 1998;13:981–993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Pettit GR, Rhodes MR. Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 1998;13:183–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Pettit GR, Lippert JW., III Anti-Cancer Drug Des. 2000;15:203–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Pettit GR, Grealish MP, Jung MK, Hamel E, Pettit RK, Chapuis J-C, Schmidt JM. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:2534–2542. doi: 10.1021/jm010119y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.a Alloatti D, Giannini G, Cabri W, Lustrati I, Marzi M, Ciacci A, Gallo G, Tinti MO, Marcellini M, Riccioni T, Guglielmi MB, Carminati P, Pisano C. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:2708–2721. doi: 10.1021/jm701362m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zou Y, Xiao C-F, Zhong R-Q, Wei W, Huang W-M, He S-J. J. Chem. Res. 2008:354–356. [Google Scholar]; c Pinney KG, Jelinek C, Edvardsen K, Chaplin DJ, Pettit GR. In: Anticancer Agents from Natural Products. Cragg GM, Kingston DGI, Newman DJ, editors. Taylor and Francis; Boca Raton, Fl: 2005. pp. 23–46. [Google Scholar]; d Cirla A, Mann J. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2003;20:558–564. doi: 10.1039/b306797c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Pettit GR. In: Anticancer Agents: Frontiers in Cancer Chemotherapy. Ojima I, Vite GD, Altmann K-H, editors. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2001. pp. 16–42. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin H-L, Chiou S-H, Wu C-W, Lin W-B, Chen L-H, Yang Y-P, Tsai M-L, Uen Y-H, Liou J-P, Chi C-W. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2007;323:365–373. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.124966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.a Zhang F, Sun C, Wu J, He C, Ge X, Huang W, Zou Y, Chen X, Qi W, Zhai Q. Pharmcol. Res. 2008;57:318–323. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sun C, Zhang F, Ge X, Yan T, Chen X, Shi X, Zhai Q. Cell Metabol. 2007;6:307–319. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pettit GR, Rhodes MR, Herald DL, Hamel E, Schmidt JM, Pettit RK. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4087–4099. doi: 10.1021/jm0205797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pettit GR, Anderson CR, Herald DL, Jung MK, Lee DJ, Hamel E, Pettit RK. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:525–531. doi: 10.1021/jm020204l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hammond GS, Saltiel J, Lamola AA, Turro NJ, Bradshaw JS, Cowan DO, Counsell RC, Vogt V, Dalton C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1964;86:3197–3217. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverberg LJ, Dillon JL, Vemishetti P. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:771–774. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ren X, Chen X, Peng K, Xie X, Xia Y, Pan X. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2002;13:1799–1804. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snider BB, Grabowski JF. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:5171–5177. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SMART (Version 5.632), SAINT (Version 6.45a), SHELXTL (Version 6.14), and SADABS (Version 2.10) Bruker AXS Inc.; Madison, WI: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 30.CCDC 736738 (3a) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for 3a. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.