Abstract

Human topoisomerase IIα utilizes a two-metal-ion mechanism for DNA cleavage. One of the metal ions (M12+) is believed to make a critical interaction with the 3′-bridging atom of the scissile phosphate, while the other (M22+) is believed to interact with a non-bridging oxygen of the scissile phosphate. Based on structural and mutagenesis studies of prokaryotic nucleic acid enzymes, it has been proposed that the active site divalent metal ions interact with type II topoisomerases through a series of conserved acidic amino acid residues. The homologous residues in human topoisomerase IIα are E461, D541, D543, and D545. To address the validity of these assignments and to delineate interactions between individual amino acids and M12+ and M22+, we individually mutated each of these acidic amino acid residues in topoisomerase IIα to either cysteine or alanine. Mutant enzymes displayed a marked loss of catalytic and DNA cleavage activity as well as a reduced affinity for divalent metal ions. Additional experiments determined the ability of wild-type and mutant topoisomerase IIα enzymes to cleave an oligonucleotide substrate that contained a sulfur atom in place of the 3′-bridging oxygen of the scissile phosphate in the presence of Mg2+, Mn2+, or Ca2+. Based on the results of these studies, we conclude that the four acidic amino acid residues interact with metal ions in the DNA cleavage/ligation active site of topoisomerase IIα. Furthermore, we propose that M12+ interacts with E461, D543, and D545 and M22+ interacts with E461 and D541.

Fundamental nuclear processes, such as replication and recombination, often generate tangles and knots in DNA (1–3). If these topological alterations in the genetic material are not successfully resolved, the ability of chromosomes to segregate during mitosis will be severely impeded (2–5).

DNA tangles and knots are removed by type II topoisomerases (2, 4, 6–9). These essential enzymes act by generating transient double-stranded breaks in DNA and passing an intact double helix through the break (4, 10). Like many enzymes that break or rejoin nucleic acids, type II topoisomerases require divalent metal ions as cofactors for catalysis (11). Magnesium appears to be the physiological metal ion used by these enzymes (11). Recent studies indicate that human topoisomerase IIα and IIβ both utilize a two-metal-ion mechanism for DNA cleavage (12, 13). This mechanism is similar to those proposed for the scission reaction of DNA gyrase (a bacterial type II topoisomerase) (14) as well as the polymerization reactions of primases and some DNA polymerases (15–17).

During the DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase IIα and IIβ, one divalent metal ion (metal ion 1) makes an important interaction with the 3′-bridging oxygen atom of the scissile phosphate (12, 13). This interaction accelerates rates of enzyme-mediated DNA scission, most likely by stabilizing the leaving group (12–14). A second metal ion (metal ion 2) appears to contact a non-bridging atom of the scissile phosphate in the active site of topoisomerase IIβ (13). This interaction plays a significant role in DNA cleavage mediated by the β isoform and greatly stimulates scission. As proposed previously, metal ion 2 is believed to stabilize the DNA transition state and/or help deprotonate the active site tyrosine (12–14, 18). Although topoisomerase IIα has an absolute requirement for metal ion 2 (12), the role of this divalent cation in its DNA cleavage reaction is unclear. It is not definitive as to whether it interacts with a non-bridging oxygen in the active site of topoisomerase IIα. However, if the interaction exists, it does not affect rates of DNA cleavage.

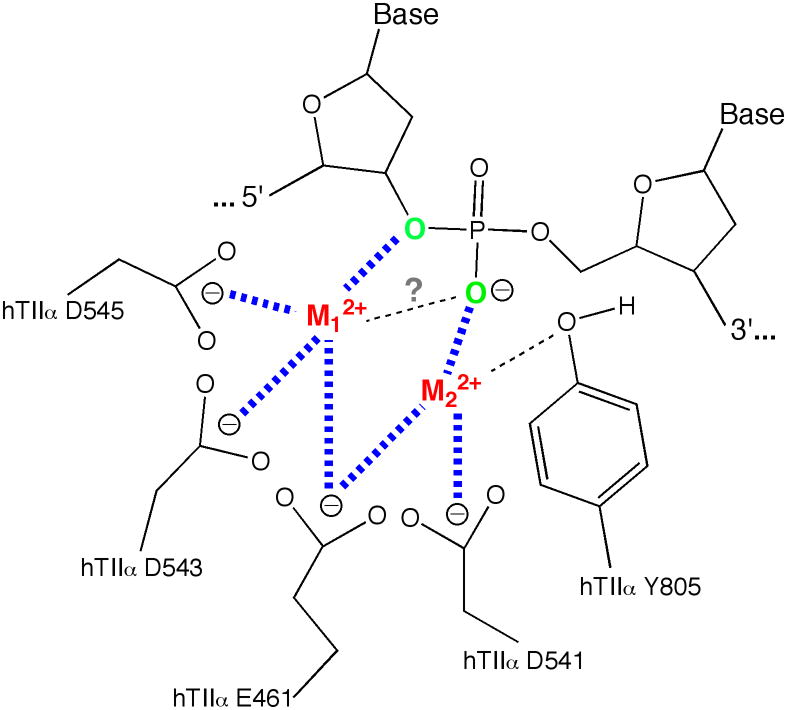

Type IA topoisomerases, type II topoisomerases, and primases share a conserved region known as the TOPRIM domain (19, 20). This region has been implicated in coordinating divalent metal ions that are used during nucleic acid cleavage, ligation, and polymerization reactions (14, 19–21). Based on structural studies of Escherichia coli topoisomerase III, primase (dnaG), and DNA gyrase, together with mutagenesis studies of DNA gyrase, it has been proposed that the divalent metal ions in the active sites of type II topoisomerases interact with the protein through a series of conserved acidic amino acid residues (Figure 1) (14, 18, 19, 22). The homologous residues in human topoisomerase IIα are E461, D541, D543, and D545 (23). These assignments are consistent with a recent crystallographic structure of the catalytic core of yeast topoisomerase II in a non-covalent complex with DNA (24). However, this latter structure contained only one divalent metal ion and the active site tyrosine residue was located too far from the scissile bond to support DNA cleavage. Thus, specific interactions between individual amino acids and the two divalent metal ions in the DNA cleavage/ligation active site of type II topoisomerases have yet to be fully elucidated.

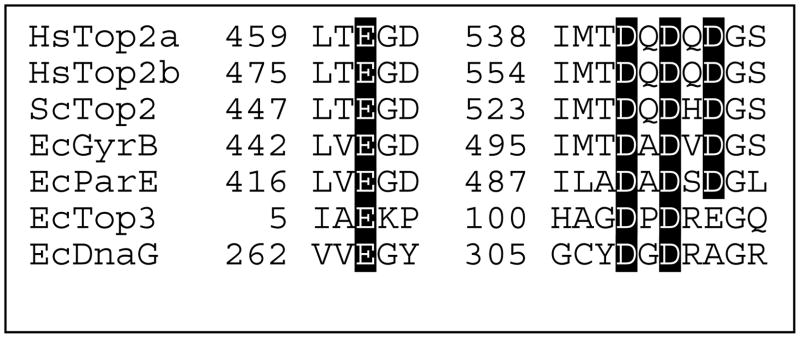

Figure 1.

Amino acids postulated to coordinate divalent metal ions in the active site of nucleic acid enzymes. Sequence alignments for enzymes that contain a TOPRIM domain, including human topoisomerase IIα (HsTop2a), topoisomerase IIβ (HsTop2b), S. cerevisiae topoisomerase II (ScTop2), E. coli Gyr B subunit of DNA gyrase (EcGyrB), E. coli Par E subunit of topoisomerase IV (EcParE), E. coli topoisomerase III (EcTop3), and E. coli DnaG (EcDnaG) are shown. Conserved acidic amino acid residues that are proposed to bind divalent metal ions are highlighted. Sequences are from Refs. (19, 23).

In an effort to more completely define interactions between divalent metal ions and type II topoisomerases, we carried out a series of kinetic and mutagenesis studies with topoisomerase IIα. Results confirm an important role for E461, D541, D543, and D545 in DNA cleavage mediated by the human enzyme and delineate contacts between individual amino acid residues and metal ions 1 and 2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Enzymes

Wild-type and mutant human topoisomerase IIα proteins were expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae JEL1Δtop1 cells and purified as described previously (25–27). Individual point mutations in human topoisomerase IIα were generated using the PCR-based Lightning Mutagenesis Kit (Strategene). D541, D543, D545, and E461 were individually mutated to either Cys or Ala in the inducible overexpression YEpWOB6 plasmid. Primer sequences were as follows: D545C forward 5′ – GGAAGATAATGATTATGACAGATCAGGACCAATGTGGTTCCCACATC – 3′; reverse 5′ – GATGTGGGAACCACATTGGTCCTGATCTGTCATAATCATTATCTTCC – 3′; D545A forward 5′ – GGAAGATAATGATTATGACAGATCAGGACCAAGCTGGTTCCCACATC – 3′; reverse 5′ – GATGTGGGAACCAGCTTGGTCCTGATCTGTCATAATCATTATCTTCC – 3′; D543C forward 5′ – GGAAGATAATGATTATGACAGATCAGTGCCAAGATGGTTCCCACATC – 3′; reverse 5′ – GATGTGGGAACCATCTTGGCACTGATCTGTCATAATCATTATCTTCC – 3′; D543A forward 5′ – GGAAGATAAGATTATGACAGATCAGGCCCAAGATGGTTCCCACATC – 3′; reverse 5′ – GATGTGGGAACCATCTTGGGCCTGATCTGTCATAATCATTATCTTCC – 3′; D541C forward 5′ – GGAAGATAATGATTATGACATGTCAGGACCAAGATGGTTCCCACATC – 3′; reverse 5′ – GATGTGGGAACCATCTTGGTCCTGACATGTCATAATCATTATCTTCC – 3′; D541A forward 5′ – GGAAGATAATGATTATGACAGCTCAGGACCAAGATGGTTCCCACATC – 3′; reverse 5′ – GATGTGGGAACCATCTTGGTCCTGAGCTGTCATAA TCATTATCTTCC – 3′; E461C forward 5′ – GAGTGTACGCTTATCCTGACTTGTGGAGATTCAGCCAAAACTTTGGCTG – 3′; reverse 5′ – CAGCCAAAGTTTTGGCTGAATCTCCACAAGTCAGGATAAGCGTACACTC – 3′; and E461A forward 5′ – GAGTGTACGCTTATCCTGACTGCGGGAGATTCAGCCAAAACTTTGGCTG – 3′; reverse 5′ – CAGCCAAAGTTTTGGCTGAATCTCCCGCAGTCAGGATAAGCGTACACTC – 3′. In all cases, mutant topoisomerase IIα genes were isolated and sequenced before being transformed into JEL1Δtop1 yeast cells. The purity of mutant enzymes was assessed by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were visualized with coomassie or silver stains (data not shown). Enzymes were >95% homogeneous. Contamination with yeast topoisomerase II was too low to quantify (<0.2%), as determined by western blot analysis using antibodies directed against the yeast type II enzyme.

Preparation of Oligonucleotides

A 50 bp duplex oligonucleotide was designed using a previously identified topoisomerase II cleavage site from pBR322 (28). Wild-type oligonucleotide sequences were generated using an Applied Biosystems DNA synthesizer. The 50-mer top and bottom sequences were 5′-TTGGTATCTGCGCTCTGCTGAAGCC↓AGTTACCTTCGGAAAAAGAGTTGGT-3′ and 5′-ACCAACTCTTTTTCCGAAGGT↓AACTGGCTTCAGCAGAGCGCAGATACCAA-3′, respectively. The arrow denotes the point of scission by topoisomerase II. The top strand was composed of two shorter sequences that produced a nick at the location of the scissile bond.

DNA containing a single 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate linkage was synthesized as described previously (29). The location of the phosphorothiolate was at the normal scissile bond on the bottom strand. Substrates containing a racemic phosphorothioate in place of the non-bridging scissile bond oxygens of the bottom strand were synthesized by Operon.

Radioactive Labeling of Oligonucleotides

[γ-32P]ATP (~5000 Ci/mmol) was obtained from ICN. Single-stranded oligonucleotides were labeled on their 5′-termini using T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs). Following labeling and gel purification, complementary oligonucleotides were annealed by incubation at 70 °C for 10 min and cooling to 25 °C.

DNA Cleavage of Oligonucleotide Substrates

DNA cleavage assays were carried out by the procedure of Deweese et al. (29). DNA cleavage reactions with wild-type or mutant human topoisomerase IIα proteins contained 200 nM enzyme and 100 nM double-stranded oligonucleotide in a total of 10 μL of DNA cleavage buffer [10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.9, 135 mM KCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 2.5% glycerol]. Unless otherwise noted, the concentration of the divalent cation added to reaction mixtures was 5 mM. In some cases, the concentration of divalent cation (MgCl2, MnCl2, or CaCl2) was varied and/or combinations of the cations were used. Experiments that monitored DNA cleavage over a range that included divalent cation concentrations below 1 mM utilized cleavage buffer that lacked EDTA. Reactions were initiated by the addition of enzyme and were incubated for 0 to 30 min at 37 °C. DNA cleavage products were trapped by the addition of 2 μL of 10% SDS followed by 2 μL of 250 mM NaEDTA, pH 8.0. Proteinase K (2 μL of 0.8 mg/mL) was added to digest the enzyme. Cleavage products were resolved by electrophoresis in a 14% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. To inhibit oxidation of cleaved oligonucleotides containing 3′-terminal –SH moieties and the formation of multimers in the gel, 100 mM DTT was added to the sample loading buffer. DNA cleavage products were visualized and quantified using a Bio-Rad Molecular Imager.

Pre-equilibrium DNA cleavage reactions were monitored for 0.5 s to 3 s using a KinTek model RQF-3 chemical quench flow apparatus (Austin, TX). Cleavage was initiated by rapidly mixing two independent solutions. The first contained a noncovalent complex formed between human topoisomerase IIα and 32P-labeled oligonucleotide in cleavage buffer that lacked divalent cation. The second solution contained cleavage buffer in which the concentration of MgCl2 was 2 times higher than normal (concentration of MgCl2 in the final reaction mixture ranged from 0.5–10 mM). The two solutions were mixed at 37 °C, and DNA cleavage was quenched with 1% SDS (v/v final concentration). Products were processed and analyzed as described above.

Pre-steady-state data were fitted using the program DynaFit (30). Best fits were obtained for plots of time courses versus metal ion concentration using least-squares regression by Levenberg-Marquardt methods. The full analysis is included in Supporting Information.

Topoisomerase II-mediated Relaxation of Plasmid DNA

DNA relaxation assays were performed according to the procedure of McClendon et al. (31). Reactions mixtures contained 0.5–20 nM wild-type or 20 nM mutant human topoisomerase IIα proteins, 1 mM ATP, and 5 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322 in a total of 20 μL of 10 mM Tris-HCL, pH 7.9, 175 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM NaEDTA, and 2.5% glycerol. Mixtures were incubated at 37 °C for 0–20 min and stopped by the addition of 3 μL of 0.5% SDS and 77 mM EDTA. Samples were mixed with 2 μL of agarose gel loading buffer [60% sucrose in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 0.5% bromophenol blue (w/v), and 0.5% xylene cyanol FF (w/v)] and subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels in 100 mM Tris-borate, pH 8.3, and 2 mM EDTA. Gels were stained for 30 min with 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. DNA bands were visualized by UV light and were quantified using an Alpha Innotech digital imaging system (San Leandro, CA). DNA relaxation was monitored by the loss of the initial supercoiled substrate.

Topoisomerase II-mediated Cleavage of Plasmid DNA

Plasmid DNA cleavage reactions were performed using the procedure of Fortune and Osheroff (32). Reaction mixtures contained 200 nM wild-type or mutant human topoisomerase II〈 proteins and 5 nM negatively supercoiled pBR322 DNA in 20 μL of DNA cleavage buffer containing 5 mM MgCl2 and 100 μM etoposide or amsacrine. DNA cleavage mixtures were incubated for 6 min at 37 °C. DNA cleavage complexes were trapped by adding 2 μL of 5% SDS followed by 2 μL of 250 mM Na2EDTA (pH 8.0). Proteinase K was added (2 μL of a 0.8 mg/mL solution), and reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C to digest topoisomerase II. Samples were mixed with 2 μL of agarose gel loading buffer, heated for 2 min at 45 °C, and subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels in 40 mM Tris-acetate (pH 8.3) and 2 mM EDTA containing 0.5 μg/mL ethidium bromide. Double-stranded DNA cleavage was monitored by the conversion of negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA to linear molecules. DNA bands were visualized and quantified as described above.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Use of Mg2+ During Topoisomerase II-mediated DNA Cleavage

As discussed earlier, human topoisomerase IIα utilizes a two-metal-ion mechanism for its DNA scission reaction. Based on the relative abilities of Mn2+ and Ca2+ to support cleavage of wild-type oligonucleotides and substrates containing 3′-bridging phosphorothiolates, it was proposed that metal ion 1 bound to topoisomerase IIα with an affinity that was ~10–fold higher than that of metal ion 2 (12). However, the interaction of the physiological metal ion, Mg2+, with topoisomerase IIα has not been explored in detail. Therefore, a kinetic approach was employed to further define the parameters of Mg2+ utilization by topoisomerase IIα.

As a first step, the cleavage of a wild-type substrate was determined over a Mg2+ concentration range of 1 μM to 10 mM (Figure 2). To simplify the analysis and increase baseline levels of scission, we used a substrate that contained a nick at the scissile bond of the unlabeled strand (12). Previous work has demonstrated that the presence of the nick enhances both the rate and level of DNA cleavage on the opposite strand (12, 33).

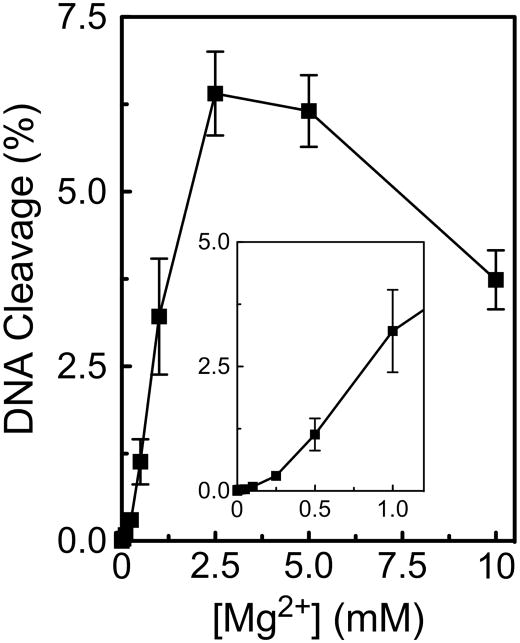

Figure 2.

Divalent metal ion concentration dependence of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage. Oligonucleotide cleavage reactions mediated by human topoisomerase IIα were performed over 30 min in the presence of 1 μM to 10 mM Mg2+. Reactions utilized a wild-type substrate that contained a nick at the scissile bond on the opposite (unlabeled) strand. The inset shows DNA cleavage levels at concentrations up to 1 mM Mg2+. Error bars represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Optimal DNA cleavage was observed at ~2.5–5.0 mM Mg2+. The decrease in enzyme activity at higher metal ion concentrations has been observed for other type II topoisomerases and most likely represents an ionic strength effect (36).

At the low end of the Mg2+ concentration range, the dependence of the metal ion appeared to be biphasic in nature. This biphasic metal ion concentration dependence suggests that there are two Mg2+ sites in the DNA cleavage/ligation domain of topoisomerase IIα and that both need to be filled in order to support scission. The initial (i.e., high affinity) phase appears to be completely filled somewhere between ~100–250 μM Mg2+, implying an apparent KD value for this site that probably is less than 100 μM. Based on the results of previous studies (12, 13), we propose that this high affinity interaction represents the binding of Mg2+ to the site of metal ion 1. One-half maximal DNA cleavage activity was observed at ~1.0–1.5 mM Mg2+. This finding suggests that Mg2+ binds to the site of metal ion 2 with an apparent KD value that is in this latter concentration range. By comparison, the concentration of free Mg2+ within the cell is estimated to be ~0.5–1.5 mM (34).

To extend the above experiments, the intrinsic KD value of human topoisomerase IIα for Mg2+ was determined by analyzing the metal ion dependence of the pre-equilibrium kinetics of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. Experiments utilized a Mg2+ concentration range of 0.5–10 mM. Since both metal ions 1 and 2 must be present in order to support DNA cleavage, we started at a concentration at which the first metal ion binding site was likely to be saturated. Thus, data from the kinetic analysis reflect primarily the interaction of Mg2+ with the second, or low affinity, metal ion binding site. In addition, since the substrate used for these studies contained a nick at the scissile bond on the unlabeled strand, the enzyme can cleave only the scissile bond on the labeled strand. As a result, the overall equation describing the reaction being monitored is reduced to the following:

Plots of percent DNA cleavage versus cation concentration were fitted to a single-exponential equation to generate apparent rate constants for the reaction at each concentration. Apparent rate constants were then plotted versus cation concentration (Figure 3) and analyzed using the program DynaFit (30).

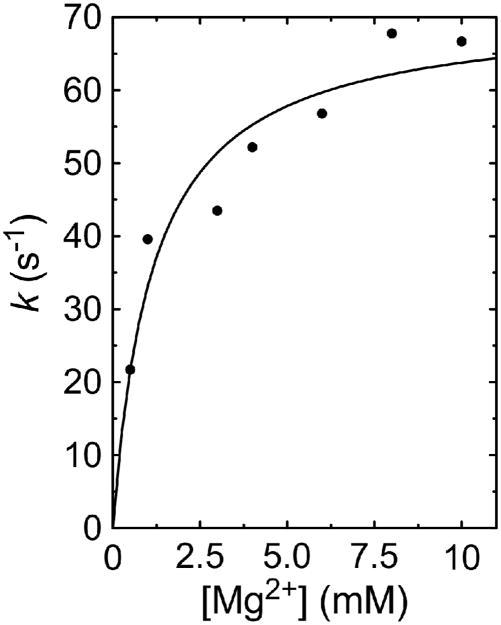

Figure 3.

Kinetic analysis of metal ion dependence during topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage. Pre-equilibrium oligonucleotide cleavage reactions mediated by human topoisomerase IIα were monitored over a time course of 5 ms to 3 s in the presence of 0.5 to 10 mM Mg2+. Reactions utilized a wild-type substrate that contained a nick at the scissile bond on the opposite (unlabeled) strand. Data points represent single exponential rate constants obtained from each reaction plotted versus metal ion concentration. A best fit curve is shown that was generated using Dynafit (30) with the equation shown in the text.

The analysis was performed using a series of values for the forward cleavage (k2) and reverse ligation (k−2) reaction rates. In all cases, best fits were obtained at k−2/k2 ratios in the range of ~40–500, implying that topoisomerase IIα ligates DNA considerably faster than it cleaves the double helix. This finding is consistent with the fact that the human type II enzyme maintains very low equilibrium levels of covalent enzyme-cleaved DNA complexes (E•DNA*•Metal) (4, 10, 33, 35).

Finally, over a wide range of k1 and k−1, best fits always yielded a k−1/k1 ratio (i.e., KD value) of ~1.2 mM. This apparent KD for the binding of Mg2+ to the second metal ion site is similar to the value obtained in the equilibrium titration experiment discussed above.

Amino Acid Residues Involved in Metal Ion Coordination

Based on crystallographic and mutagenesis studies with bacterial topoisomerases and primase, it has been proposed that divalent metal ions are coordinated to human topoisomerase IIα through a series of acidic amino acid residues (see Figure 1) (12, 14, 18–22). Metal ion 1 is postulated to interact with E461, D543, and D545, while metal ion 2 is postulated to interact with E461 and D541 (12). These residues are highly conserved among the type IA and type IIA families of topoisomerases (19, 21, 23).

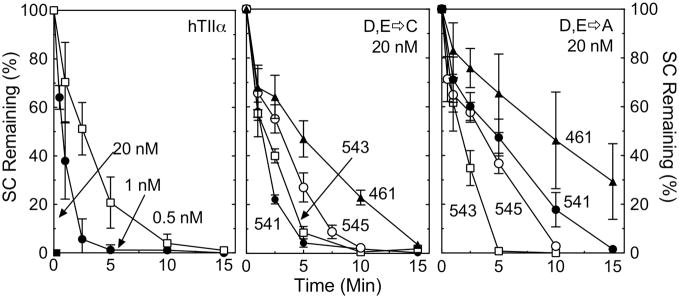

To address the validity of these assignments in human topoisomerase IIα, the four acidic amino acids were individually mutated to either Ala (to remove functional groups) or Cys (to potentially enhance interactions with thiophilic divalent metal ions). Each of the mutant enzymes was purified and characterized. As seen in Figure 4, the overall catalytic activity of the mutant enzymes, assessed by the ability to relax negatively supercoiled plasmid DNA in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+, was dramatically reduced as compared to that of the wild-type enzyme. Even the most active of the mutant enzymes, hTop2αD541C, required 10– to 20–fold higher enzyme concentrations than wild-type topoisomerase IIα to achieve similar rates of DNA relaxation. The least active mutant enzyme, hTop2αE461A, required >40–fold higher concentrations.

Figure 4.

DNA relaxation activity of mutant enzymes. DNA relaxation assays were carried out using negatively supercoiled pBR322 and wild-type or mutant topoisomerase IIα enzymes in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+. Left panel, the plot shows the loss of supercoiled plasmid in the presence of wild-type topoisomerase IIα at 0.5, 1, or 20 nM. Middle panel, the plot shows the loss of supercoiled plasmid in the presence of the D,E->C mutant enzymes at 20 nM. Right panel, the plot shows the loss of supercoiled plasmid in the presence of the D,E->A mutant enzymes at 20 nM. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of at least two independent experiments.

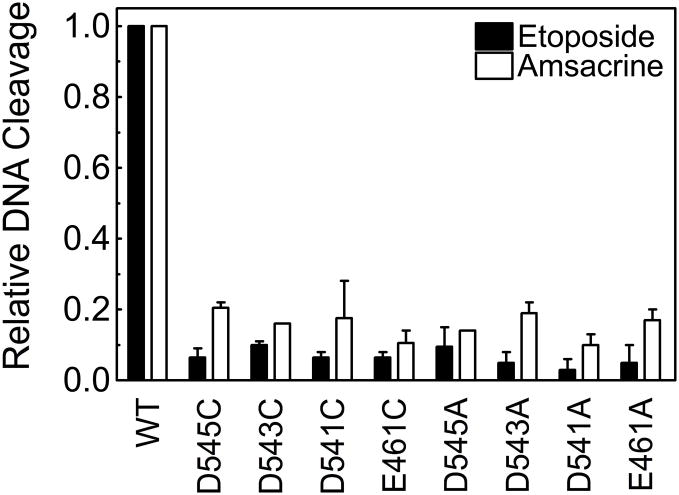

In order to examine the roles of the acidic amino acids in coordinating divalent metal ions during the scission reaction, the ability of the mutant enzymes to cleave negatively supercoiled DNA in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+ was determined. Equilibrium levels of cleavage generated by the mutant enzymes were too low to quantify reliably. Therefore, cleavage experiments were carried out in the presence of either 100 μM etoposide or amsacrine. Both of these anticancer drugs are potent topoisomerase II poisons that increase levels of enzyme-mediated DNA scission by interfering with the ability of topoisomerase II to ligate cleaved molecules. Once again, all of the mutant enzymes displayed a level of activity that was considerably lower than that of wild-type topoisomerase IIα (Figure 5). Together with the DNA relaxation results, these findings provide strong evidence that E461, D541, D543, and D545 play important roles in catalysis mediated by human topoisomerase IIα.

Figure 5.

Plasmid DNA cleavage mediated by mutant enzymes. Cleavage assays were performed using negatively supercoiled pBR322 and wild-type or mutant topoisomerase IIα enzymes in the presence of 100 μM etoposide (closed bars) or 100 μM amsacrine (open bars). Results for wild-type (WT) and each of the mutant enzymes are shown. Data are plotted relative to the WT enzyme. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of two independent experiments.

In addition to the requirement for divalent metal ions in the DNA cleavage/ligation active site of type II topoisomerases, these enzymes also utilize a divalent metal to coordinate the high energy ATP cofactor in a separate ATPase active site (36). To ensure that the mutations affected metal ion coordination only in the cleavage/ligation active site, the ability of two mutant enzymes to hydrolyze ATP in absence of DNA was determined using a thin layer chromatography technique (37). hTop2αE461C and hTop2αD543C were chosen for this study because they represent one of the least active and one of the most active mutants, respectively. Despite the fact that both mutant enzymes displayed a relaxation activity that was less than 5% that of wild-type, rates of ATP hydrolysis were ~70% and 200% that of wild-type topoisomerase IIα (data not shown). Since the effects of the mutations on ATPase activity did not reflect their effects on DNA relaxation, it is concluded that the primary defect in the enzymes is their inability to cleave DNA efficiently.

Interactions Between Acidic Amino Acid Residues and Metal Ions 1 and 2

In an effort to delineate interactions between specific amino acid residues and metal ions 1 and 2, the ability of wild-type topoisomerase IIα and the mutant enzymes to cleave a series of oligonucleotides was assessed. Three different substrates were employed for these experiments. All had the same nucleotide sequence. However, one contained a wild-type 3′-bridging oxygen at the scissile bond, while the other two substituted a sulfur atom at either the non-bridging (phosphorothioate) or 3′-bridging (phosphorothiolate) position. In addition to the different substrates, DNA cleavage was determined in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+, Mn2+, or Ca2+. Within this series, Mn2+ is the “softest,” or most thiophilic metal, and Mg2+ and Ca2+ are harder, or less thiophilic (38–40). Soft metal ions often prefer sulfur over oxygen as an inner-sphere ligand, while hard metals usually coordinate more readily with oxygen (16, 38–43). If there is a direct interaction between the metal ion and a scissile phosphate atom (or a sulfur-containing amino acid) that facilitates catalysis, relative levels or rates of scission with substrates containing a sulfur atom in place of the oxygen should increase in the presence of soft (thiophilic) metals (12, 16, 41–43). Conversely, less cleavage should be generated in reactions that contain hard metals (12, 16, 41–43).

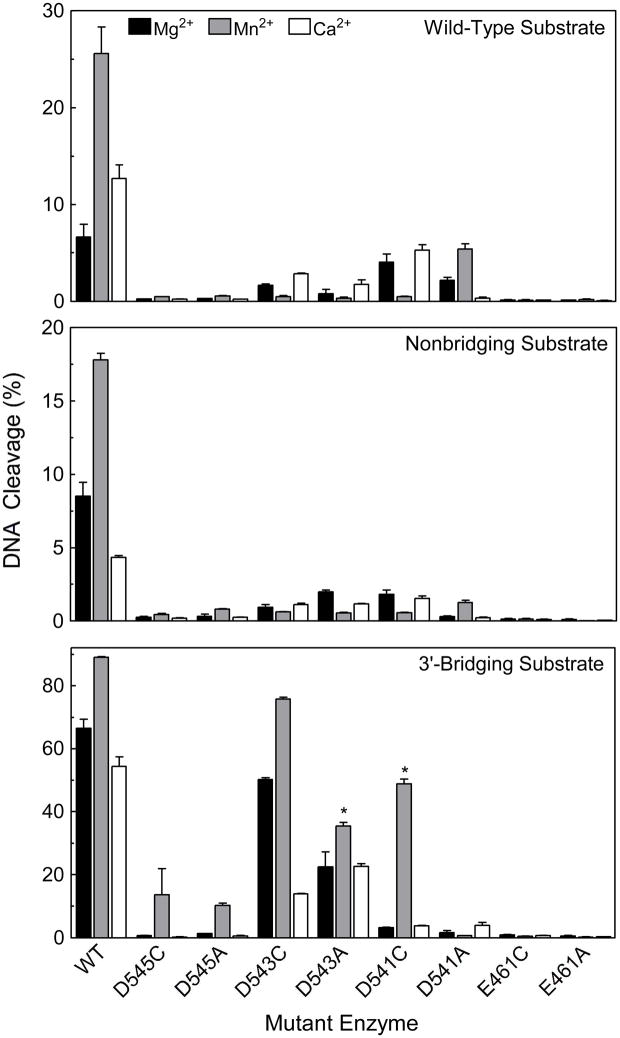

As seen in Figure 6 (Top), compared to wild-type human topoisomerase IIα, levels of cleavage of the wild-type substrate were dramatically reduced for all of the mutant enzymes. Mutations at D545 and E461 resulted in enzymes that displayed almost no cleavage activity, while marginal levels of cleavage were observed with the D543 and D541 mutant enzymes. It is notable that hTop2αD541C and hTop2αD543C, which among the D->C mutations displayed the greatest ability to cleave DNA in the presence of Mg2+, also displayed the greatest ability to relax plasmid DNA in the presence of Mg2+. However, a similar correlation was not observed among the D->A mutations.

Figure 6.

Oligonucleotide DNA cleavage mediated by mutant enzymes. All substrates contained a nick at the scissile bond on the opposite (unlabeled) strand. Data were generated with a wild-type (top panel), nonbridging phosphorothioate (middle panel), or 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate (bottom panel) substrate. Oligonucleotides were cleaved in the presence of 5 mM Mg2+ (black bars), Mn2+ (gray bars), or Ca2+ (open bars) with wild-type human topoisomerase IIα (WT), or mutant enzymes that contained D545C, D545A, D543C, D543A, D541C, D541A, E461C, or E461A. DNA cleavage data for the D543A and D541C enzymes (denoted by asterisks) in the bottom panel (3′-bridging phosphorothiolate substrate) were generated in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+. In these cases, optimal levels of DNA scission were observed at 1 mM rather than 5 mM metal ion (see Figure 7). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of two independent experiments or the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

In all cases, poor activity was seen with the substrate that contained the non-bridging phosphorothioate (Figure 6 Middle). This is consistent with the previous finding that this substrate generally is cleaved more poorly than wild-type oligonucleotides.

Unlike the other substrates, oligonucleotides that contain a 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate cannot be ligated appreciably by topoisomerase IIα (29). As a result, much higher levels of cleavage complexes accumulate with this substrate. This property provides a more sensitive assay to determine the ability of a given enzyme to cleave DNA.

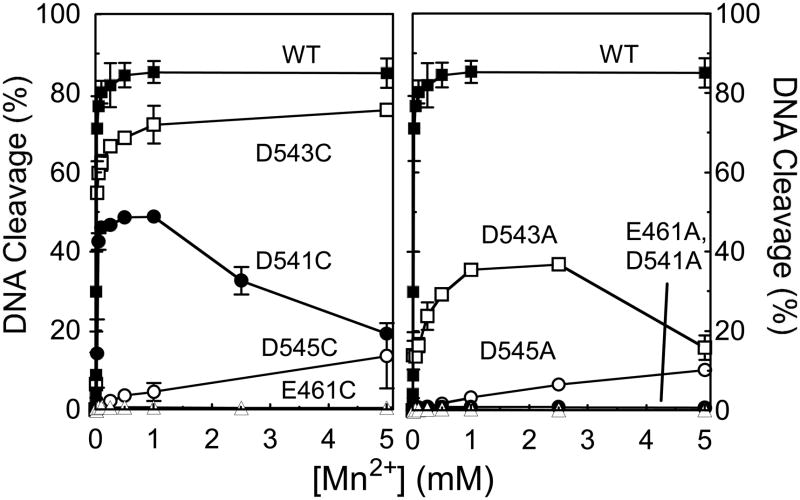

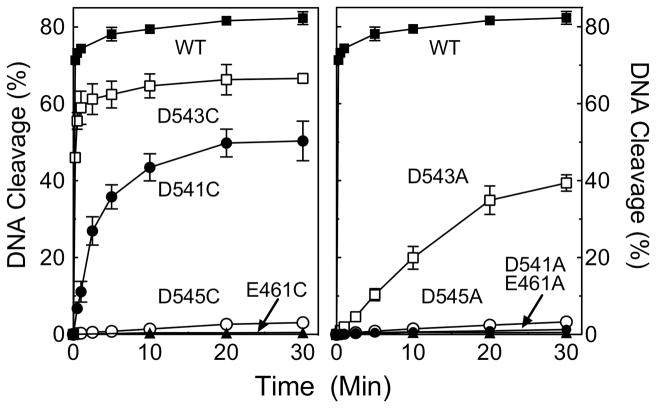

As observed with the wild-type and non-bridging phosphorothioate oligonucleotides, hTop2αE461C and hTop2αE461A displayed virtually no ability to cleave the 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate substrate (Figures 6 Bottom, 7, and 8). This finding is consistent with the proposal that E461 plays an important role in coordinating both metal ions 1 and 2. However, in contrast to the E461 mutants, modest to high levels of DNA scission were generated by most of the aspartic acid mutants (Figures 6 Bottom, 7, and 8). In all cases, higher levels and rates of cleavage were observed in the D->C than in the D->A mutants when Mn2+ was employed as the divalent metal ion. Since Mn2+ is a thiophilic metal ion, this finding implies a direct interaction between divalent cations and D541, D543, and D545.

hTop2αD545C and hTop2αD545A cleaved the 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate, but did so only in the presence of Mn2+. The fact that the DNA cleavage activity of the D545 mutants can be rescued only in the presence of a thiophilic metal ion and an S–P scissile bond strongly suggests that this residue coordinates metal ion 1, as predicted by the two-metal ion model for topoisomerase IIα. As determined by the metal ion concentration required to yield ½ maximal DNA cleavage, hTop2αD545C and hTop2αD545A displayed reduced affinities for Mn2+ [apparent KD ≈ 2.5 mM for each mutant as compared to ~14 μM for the wild-type enzyme (Figure 7)] and decreased rates of cleavage [rate ≈ 1000-fold lower than that of the wild-type enzyme (Figure 8)].

Figure 7.

Mn2+ concentration dependence of topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage of a 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate substrate. The oligonucleotide contained a nick at the scissile bond on the opposite (unlabeled) strand. Reactions with wild-type or mutant human topoisomerase IIα enzymes were carried out in the presence of 1 μM to 10 mM Mn2+. Left panel, DNA cleavage mediated by wild-type (WT, closed squares) or D,E->C mutant enzymes (E461C, closed triangles; D541C, closed circles; D543C, open squares; D545C, open circles). Right panel, cleavage mediated by wild-type (WT, closed squares) or D,E->A mutant enzymes (E461A, closed triangles; D541A, closed circles; D543A, open squares; D545A, open circles). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of two independent experiments or the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Figure 8.

Time course for topoisomerase II-mediated cleavage of a 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate substrate in the presence of Mn2+. The oligonucleotide contained a nick at the scissile bond on the opposite (unlabeled) strand. Reactions with wild-type or mutant human topoisomerase IIα enzymes were carried out in the presence of 1 mM Mn2+ over a time course from 15 s to 30 min. Left panel, DNA cleavage mediated by wild-type (WT, closed squares) or D,E->C mutant enzymes (E461C, closed triangles; D541C, closed circles; D543C, open squares; D545C, open circles). Right panel, cleavage mediated by wild-type (WT, closed squares) or D,E->A mutant enzymes (E461A, closed triangles; D541A, closed circles; D543A, open squares; D545A, open circles). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean of two independent experiments or the standard deviation of three independent experiments.

hTop2αD543C and hTop2αD543A cleaved the phosphorothiolate substrate in the presence of all three metal ions (Mg2+, Mn2+, or Ca2+). However, the highest levels of scission always were observed with Mn2+, the most thiophilic metal ion of the three. Once again, these data support the proposed interaction of D543 with metal ion 1. As above, hTop2αD543C and hTop2αD543A displayed decreased affinities for Mn2+ [apparent KD ≈ 20 μM and 140 μM, respectively (Figure 7)] and decreased rates of cleavage [rates ≈ 2- and 40-fold lower than that of the wild-type enzyme, respectively (Figure 8)].

The interpretation of results with hTop2αD541C and hTop2αD541A is less straightforward. The two-metal-ion mechanism predicts that D541 interacts with metal ion 2. The finding that hTop2αD541A cannot be rescued more than a few percent by any of the divalent metal ions (Figures 6 Bottom, 7, and 8) is consistent with this postulate. hTop2αD541C is, however, rescued by Mn2+, but not by the other two divalent cations. As above, the affinity of Mn2+ (apparent KD ≈ 34 μM, Figure 7) and rates of DNA cleavage (rate ≈ 10-fold lower than that of the wild-type enzyme, Figure 8) were reduced as compared to topoisomerase IIα. The fact that the cleavage activity of the 3′-bridging S–P bond is seen only in the presence of a thiophilic metal ion could imply that D541 coordinates with metal ion 1 rather than 2. However, if this latter interpretation were correct, it is likely that hTop2αD541A would also support DNA cleavage in the presence of Mn2+, as observed for hTop2αD545A and hTop2αD543A. Therefore, an alternative and more likely explanation for the Mn2+-specific activity of hTop2αD541C is that D541 binds metal ion 2, and the –SH group of the cysteine (which is not present in the D->A mutation) rather than the S–P scissile bond coordinates the metal ion. Further experimentation will be necessary to resolve this issue more fully.

Use of Two Metal Ions for DNA Cleavage by Human Topoisomerase IIα

Topoisomerase IIα utilizes two metal ions to support its DNA cleavage activity. This was demonstrated by experiments that compared levels of DNA cleavage monitored in the presence of Ca2+, Mn2+, or a combination of the two divalent metal ions (12). Near saturating concentrations of Ca2+ were paired with sub-saturating concentrations of Mn2+. Rates of scission of a 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate substrate generated by wild-type topoisomerase IIα in the presence of both cations were >10–fold higher than predicted by the arithmetic sum of cleavage seen when either individual metal ion was employed (12).

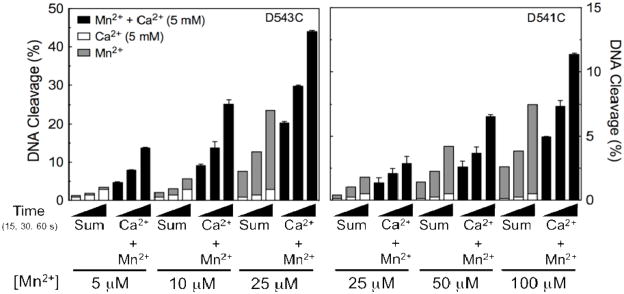

Similar experiments were carried out with two mutant enzymes, hTop2αD543C and hTop2αD541C. These two enzymes were chosen because both supported high levels of DNA scission with the 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate in the presence of Mn2+. Results are shown in Figure 9. In both cases, there was a greater than predicted effect of the two metal ions on DNA cleavage. Therefore, it appears that the mutant enzymes still employ a two-metal-ion mechanism for topoisomerase II-mediated DNA cleavage.

Figure 9.

Cleavage of a 3′-bridging phosphorothiolate oligonucleotide substrate by topoisomerase IIα mutant enzymes in the presence of divalent metal ion combinations. The oligonucleotide contained a nick at the scissile bond on the opposite (unlabeled) strand. DNA cleavage is shown for hTop2αD543C (left panel) and hTop2αD541C (right panel). Reactions were carried out for 15, 30 or 60 s in the presence of 5 mM Ca2+ alone (open bars), 5–25 μM (hTop2αD543C) or 25–100 μM (hTop2αD541C) Mn2+ alone (gray bars), or a mixture of 5 mM Ca2+ and 5–25 μM (hTop2αD543C) or 25–100 μM (hTop2αD541C) Mn2+ (Ca2+ + Mn2+, closed bars). The calculated arithmetic sum of DNA cleavage from reactions containing either Ca2+ or Mn2+ alone also is shown (Sum, stacked open and gray bars, respectively). All data represent the average of at least two independent experiments. Error bars for reactions carried out in the presence of Ca2+ + Mn2+ are shown. Error bars for reactions carried out in the presence of Ca2+ or Mn2+ alone are not shown for simplicity.

It is notable that the two-metal-ion enhancement of DNA scission with hTop2αD543C and hTop2αD541C was not as great as observed with the wild-type enzyme. This finding is consistent with the fact that neither mutant enzyme is able to utilize Ca2+ nearly as well as wild-type topoisomerase IIα. Consequently, the effect of the two metal ions, while present, is reduced.

A Model for the Use of Divalent Metal Ions for DNA Cleavage Mediated by Human Type II Topoisomerases

Based on previous structural, mutagenesis, and kinetic studies, it has been proposed that human type II topoisomerases utilize a two-metal ion mechanism for their DNA cleavage reaction (Figure 10) (12–14). In this model, there is an important interaction between metal ion 1 and the 3′-bridging atom of the scissile phosphate that accelerates rates of enzyme-mediated DNA cleavage. There also appears to be an interaction between metal ion 2 and a non-bridging oxygen of the scissile phosphate. This interaction plays a significant role in DNA cleavage mediated by topoisomerase IIβ (13). Although topoisomerase IIα has an absolute requirement for metal ion 2, the proposed interaction with the non-bridging oxygen has only a modest effect on rates of DNA cleavage.

Figure 10.

Metal ion interactions in the DNA cleavage/ligation active site of human topoisomerase IIα. Details are described in the text. The model postulates that metal ion 1 (M12+, shown in red) interacts with E461, D543, and D545 and metal ion 2 (M22+, shown in red) interacts with E461 and D541. M12+ makes a critical interaction with the 3′-bridging atom (shown in green) of the scissile phosphate (bond shown in blue), which most likely is needed to stabilize the leaving 3′-oxygen (left, shown in green). M22+ is required for DNA scission and likely interacts with the non-bridging oxygen (shown in green) during scission. This divalent cation may stabilize the DNA transition state and/or help deprotonate the active site tyrosine. The model was adapted from Ref. (14).

Previous studies have predicted an interaction between several acidic amino acid residues and the metal ions in type II topoisomerases. Mutagenesis studies have confirmed the importance of some of these residues in the bacterial type II enzyme, DNA gyrase, and in human topoisomerase IIβ (14, 22). However, the importance of the homologous residues in human topoisomerase IIα (E461, D541, D543, and D545) had not been demonstrated. In addition, while interactions between specific amino acid residues and metal ions 1 and 2 have been proposed, assignments have not been validated by enzymological studies for any type II enzyme.

Experiments were carried out that monitored DNA relaxation and cleavage (levels, rates, and metal ion concentration dependence) by mutant enzymes in which four acidic amino acid residues were individually converted to either a cysteine or an alanine. Results of these studies confirm the importance of E461, D541, D543, and D545 for the activity of human topoisomerase IIα and strongly suggest that each plays a role in metal ion binding. Furthermore, we propose that D543 and D545 play an important role in coordinating metal ion 1, that D541 plays an important role in coordinating metal ion 2, and that E461 plays an important role in coordinating both metal ions. The present study refines the two-metal-ion model for human topoisomerase II and provides a better-developed platform for additional studies regarding the role of metal ions in topoisomerase II-mediated processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Jo Ann Byl for helpful discussions regarding the preparation of mutant enzymes and ATP hydrolysis. We are grateful to Amanda C. Gentry, Adam C. Ketron, and Steven L. Pitts for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. Robert Eoff for instrument training and helpful discussions regarding rapid quench kinetics.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health research grants GM33944 and GM53960. JED was a trainee under grant T32 CA09592 from the National Institutes of Health.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

Data and parameters for the kinetic analysis are available online in Supporting Information. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Kanaar R, Cozzarelli NR. Roles of supercoiled DNA structure in DNA transactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1992;2:369–379. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang JC. Cellular roles of DNA topoisomerases: a molecular perspective. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:430–440. doi: 10.1038/nrm831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates AD, Maxwell A. DNA Topology. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McClendon AK, Osheroff N. DNA topoisomerase II, genotoxicity, and cancer. Mutat Res. 2007;623:83–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Falaschi A, Abdurashidova G, Sandoval O, Radulescu S, Biamonti G, Riva S. Molecular and Structural Transactions at Human DNA Replication Origins. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1705–1712. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.14.4495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nitiss JL. Investigating the biological functions of DNA topoisomerases in eukaryotic cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1400:63–81. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(98)00128-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang JC. DNA topoisomerases. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:635–692. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.003223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin CA, Marsh KL. Eukaryotic DNA topoisomerase IIβ. BioEssays. 1998;20:215–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199803)20:3<215::AID-BIES5>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Champoux JJ. DNA topoisomerases: structure, function, and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:369–413. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deweese JE, Osheroff N. The DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase II: wolf in sheep’s clothing. Nuc Acids Res. 2009;37:738–749. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sissi C, Palumbo M. Effects of magnesium and related divalent metal ions in topoisomerase structure and function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:702–711. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deweese JE, Burgin AB, Osheroff N. Human topoisomerase IIα uses a two-metal-ion mechanism for DNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4883–4893. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deweese JE, Burch AM, Burgin AB, Osheroff N. Use of divalent metal ions in the DNA cleavage reaction of human type II topoisomerases. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1862–1869. doi: 10.1021/bi8023256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noble CG, Maxwell A. The role of GyrB in the DNA cleavage-religation reaction of DNA gyrase: a proposed two metal-ion mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:361–371. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00049-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beese LS, Friedman JM, Steitz TA. Crystal structures of the Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I complexed with deoxynucleoside triphosphate and pyrophosphate. Biochemistry. 1993;32:14095–14101. doi: 10.1021/bi00214a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curley JF, Joyce CM, Piccirilli JA. Functional evidence that the 3′-5′ exonuclease domain of Escheria coli DNA polymerase I employs a divalent metal ion in leaving group stabilization. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:12691–12692. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kato M, Ito T, Wagner G, Richardson CC, Ellenberger T. Modular architecture of the bacteriophage T7 primase couples RNA primer synthesis to DNA synthesis. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1349–1360. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00195-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leontiou C, Lakey JH, Lightowlers R, Turnbull RM, Austin CA. Mutation P732L in human DNA topoisomerase IIβ abolishes DNA cleavage in the presence of calcium and confers drug resistance. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:130–139. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.015933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aravind L, Leipe DD, Koonin EV. Toprim--a conserved catalytic domain in type IA and II topoisomerases, DnaG-type primases, OLD family nucleases and RecR proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4205–4213. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podobnik M, McInerney P, O’Donnell M, Kuriyan J. A TOPRIM domain in the crystal structure of the catalytic core of Escherichia coli primase confirms a structural link to DNA topoisomerases. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:353–362. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger JM, Fass D, Wang JC, Harrison SC. Structural similarities between topoisomerases that cleave one or both DNA strands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7876–7881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.West KL, Meczes EL, Thorn R, Turnbull RM, Marshall R, Austin CA. Mutagenesis of E477 or K505 in the B′ domain of human topoisomerase II beta increases the requirement for magnesium ions during strand passage. Biochemistry. 2000;39:1223–1233. doi: 10.1021/bi991328b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caron PR, Wang JC. Appendix II: Alignment of primary sequences of DNA topoisomerases. Adv Pharmacol. 1994;29B:271–297. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)61143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dong KC, Berger JM. Structural basis for gate-DNA recognition and bending by type IIA topoisomerases. Nature. 2007;450:1201–1205. doi: 10.1038/nature06396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Worland ST, Wang JC. Inducible overexpression, purification, and active site mapping of DNA topoisomerase II from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4412–4416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Elsea SH, Hsiung Y, Nitiss JL, Osheroff N. A yeast type II topoisomerase selected for resistance to quinolones. Mutation of histidine 1012 to tyrosine confers resistance to nonintercalative drugs but hypersensitivity to ellipticine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1913–1920. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kingma PS, Greider CA, Osheroff N. Spontaneous DNA lesions poison human topoisomerase IIα and stimulate cleavage proximal to leukemic 11q23 chromosomal breakpoints. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5934–5939. doi: 10.1021/bi970507v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fortune JM, Dickey JS, Lavrukhin OV, Van Etten JL, Lloyd RS, Osheroff N. Site-specific DNA cleavage by Chlorella virus topoisomerase II. Biochemistry. 2002;41:11761–11769. doi: 10.1021/bi025802g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deweese JE, Burgin AB, Osheroff N. Using 3′-bridging phosphorothiolates to isolate the forward DNA cleavage reaction of human topoisomerase IIα. Biochemistry. 2008;47:4129–4140. doi: 10.1021/bi702194x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuzmic P. Program DYNAFIT for the analysis of enzyme kinetic data: application to HIV proteinase. Anal Biochem. 1996;237:260–273. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McClendon AK, Rodriguez AC, Osheroff N. Human topoisomerase IIα rapidly relaxes positively supercoiled DNA: implications for enzyme action ahead of replication forks. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39337–39345. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fortune JM, Osheroff N. Merbarone inhibits the catalytic activity of human topoisomerase IIα by blocking DNA cleavage. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:17643–17650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.28.17643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deweese JE, Osheroff N. Coordinating the two protomer active sites of human topoisomerase II: nicks as topoisomerase II poisons. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1439–1441. doi: 10.1021/bi8021679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grubbs RD. Intracellular magnesium and magnesium buffering. Biometals. 2002;15:251–259. doi: 10.1023/a:1016026831789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mueller-Planitz F, Herschlag D. Coupling between ATP binding and DNA cleavage by DNA topoisomerase II: A unifying kinetic and structural mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:17463–17476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M710014200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Osheroff N. Role of the divalent cation in topoisomerase II mediated reactions. Biochemistry. 1987;26:6402–6406. doi: 10.1021/bi00394a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kingma PS, Fortune JM, Osheroff N. Topoisomerase II-catalyzed ATP hydrolysis as monitored by thin-layer chromatography. Methods Mol Biol. 2001;95:51–56. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-057-8:51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pearson RG. Acids and Bases. Science. 1966;151:172–177. doi: 10.1126/science.151.3707.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pecoraro VL, Hermes JD, Cleland WW. Stability constants of Mg2+ and Cd2+ complexes of adenine nucleotides and thionucleotides and rate constants for formation and dissociation of MgATP and MgADP. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5262–5271. doi: 10.1021/bi00317a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sigel RKO, Song B, Sigel H. Stabilities and structures of metal ion complexes of adenosine 5′-O-thiomonophosphate (AMPS2−) in comparison with those of its parent nucleotide (AMP2−) in aqueous solution. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:744–755. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Basu S, Strobel SA. Thiophilic metal ion rescue of phosphorothioate interference within the Tetrahymena ribozyme P4-P6 domain. RNA. 1999;5:1399–1407. doi: 10.1017/s135583829999115x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sontheimer EJ, Gordon PM, Piccirilli JA. Metal ion catalysis during group II intron self-splicing: parallels with the spliceosome. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1729–1741. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.13.1729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Szewczak AA, Kosek AB, Piccirilli JA, Strobel SA. Identification of an active site ligand for a group I ribozyme catalytic metal ion. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2516–2525. doi: 10.1021/bi011973u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.