Abstract

Objective

Identifying genotyping errors is an important issue in genetic research, yet it has been relatively less studied in samples consisting of unrelated individuals. In this article, we consider several models of genotyping errors, which were originally proposed for pedigree data, for unrelated population samples with single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotype data. The mathematical constraints are investigated for detecting genotyping errors without resampling replicates or genotyping relatives.

Methods

For the various proposed genotyping error models, we unveil the conditions under which the parameters are identifiable. These results are verified through applications to simulated and real SNP data.

Results

We show that, with constraints, two particular models provide both identifiable error rate and allele frequencies of an SNP for unrelated population data. The simulation study shows that these two models present unbiased estimates for the allele frequencies. One of the models also gives an unbiased estimate for the genotyping error rate.

Conclusion

While the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test can be used to detect genotyping errors, a key advantage of these models is the explicit estimates of genotyping error rates and allele frequencies. This work may help researchers to estimate error rates and to use the estimates in their analysis to increase power and decrease bias, without the extra work of genotyping family members or replicates.

Key Words: Genotyping error, Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), Identifiability

Introduction

Even with the rapid advancement of molecular technologies for genotyping, genotyping errors are still unavoidable, leading to false positive results, false negative results, or both when these errors are not treated appropriately [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Many studies have reported the effects of genotyping errors in genetic studies [3,4,5,6,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. It has been shown that, in linkage studies, an error rate of as low as 1–2% can have a substantial impact on the study results [4]. In haplotype analysis, a 1% genotyping error rate can reduce the accuracy of some statistical methods by as much as 60%; with a 10% error rate, no method can have an accuracy of greater than 30% [32]. Gordon et al. showed that in case-control studies, an increased genotyping error rate requires a larger sample size necessary (SSN) to maintain the same asymptotic Type I and Type II error rates [34]. They further showed that every 1% increase in the sum of genotyping error rates requires a 2–8% increase in both case and control SSN [34]. The necessity of confronting this issue is fortified by the fact that all studies in which errors were checked reported non-negligible error rates of from 0.2% to more than 15% per locus [5].

Although the occurrence and consequence are similar, genotyping errors have various causes, generally resulting from four origins. First, variation in DNA sequence, such as the occurrence of null alleles in microsatellite studies, may result in failure to amplify an allele and may thus generate a genotyping error [5, 38]. Second, an error can also originate from low quantity or low quality of DNA. Allelic dropouts and false alleles can be induced from a low number of target DNA molecules [39]. Low quality of DNA may be encountered in forensic studies and in the study of rare diseases for which affected individuals are very difficult to recruit and in turn low-quality DNA samples are collected and studied. Third, genotyping errors can be generated due to the limitations in the available technologies, such as the ‘+A artefact’ in PCR [40] and shortcomings in genotype scoring software [4, 41]. Fourth, human factors are the main cause of genotyping errors in many genetic studies [3, 5, 6]. These four causes, as well as others, can also sometimes interact to generate genotyping errors which further complicates the situation [5]. Because so many factors can lead to genotyping errors, it is likely that all data sets have errors [4, 5].

Although the identification and treatment of genotyping errors is an important issue in genetic studies and has received increasing attention in recent years [2,3,4,5, 8,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50], few studies have addressed genotyping errors in samples consisting of unrelated individuals [5]. Most of the methods proposed focus on pedigree data [4,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,50,51,52], and the errors are detected mostly through Mendelian consistency checking and/or Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) testing. Few methods deal with genotyping errors for unrelated population data [8, 13, 15, 25, 48, 53], and all these methods rely on external ‘validation’ study or the use of replicates to get estimates of error rates (i.e., error rates are assumed to be known in the main study). To the best of our knowledge, Scheet and Stephens [54] were the first to detect genotyping errors directly from genotype data of unrelated individuals. However, their model may have an identifiability issue that will be explained below.

In the present article, we consider several models, which were originally proposed for pedigree data, to detect genotyping errors in unrelated population samples and investigate the identifiability of the parameters in these models. The performance of these models is then assessed through simulations. We also demonstrate the practical utility of two particular models by applying them to a data set from the HapMap project.

Methods

Let 1 and 2 denote the two alleles at a biallelic marker under study; p1 and p2 denote the frequencies of alleles 1 and 2, respectively (p1 + p2 = 1); and the numbers of the observed three genotypes (1 1), (1 2), and (2 2) be n1, n2, and n3 so that the sample size n = n1 + n2 + n3. Let O denote the observed genotype and T denote the true genotype, which may not be directly observable because of genotyping errors, for an individual. Although there are three observations (n1, n2, and n3), there are only two degrees of freedom because of the constraint n = n1 + n2 + n3. Therefore, given the observed genotype data, any model with more than two parameters cannot be identified uniquely. Because the model of Scheet and Stephens [54] has three parameters (one parameter for allele frequency and two parameters for error rates), its parameters cannot be uniquely determined by the distribution of O, i.e., the parameters are not identifiable. Strictly speaking, a parameter θ for a family of distributions {f(x ∣ θ):θ ∈Θ} is identifiable if distinct values of θ correspond to distinct distributions. Identifiability is a property of the model, not of an estimator or estimation procedure. If the model is not identifiable, it is difficult to make an inference [55]. We do note that, even though the model parameters are not identifiable, it is still acceptable to use the error models to simulate data, as performed in Gordon et al. [34]. We assume that the underlying true genotype data are in HWE, and that no data are missing.

The first model, the so-called allelic model, assumes that the errors are induced randomly and independently into alleles. This model involves two error rates defined below

∊1 = Pr(observed allele is 2 ∣ true allele is 1)

∊2 = Pr(observed allele is 1 ∣ true allele is 2).

This model has been presented and used by other researchers [48, 56]. Table 1 shows the genotype penetrances, i.e., the probability of observing one genotype given the true genotype [4, 34, 48], for this model.

Table 1.

Genotype penetrances for different error models

| Model | True genotype | Observed genotype |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1 1) | (1 2) | (2 2) | ||

| Allelic model | (1 1) | (1 – ε1)2 | 2ε1(1 – ε1) | ε12 |

| (1 2) | ε2(1 – ε1) | ε1ε2 + (1 – ε1)(1 – ε2) | ε1(1 – ε2) | |

| (2 2) | ε22 | 2 ε2(1 – ε2) | (1 – ε2)2 | |

| Simplified allelic model | (1 1) | 1 – 2ε | 2ε | 0 |

| (1 2) | ε | 1 – 2ε | ε | |

| (2 2) | 0 | 2ε | 1 – 2ε | |

| Sobel's general model | (1 1) | 1 – (ε3 + ε4) | ε4 | ε3 |

| (1 2) | ε1/2 | 1 – ε1 | ε1/2 | |

| (2 2) | ε3 | ε4 | 1 – (ε3 + ε4) | |

| Scheet's allelic model | (1 1) | 1 – ε | ε | 0 |

| (1 2) | ε∗/2 | 1 – ε∗ | ε∗/2 | |

| (2 2) | 0 | ε | 1 – ε | |

| Homo-heterozygote model | (1 1) | 1 – ε | ε | 0 |

| (1 2) | ε | 1 – 2ε | ε | |

| (2 2) | 0 | ε | 1 – ε | |

| Genotypic model | (1 1) | 1 – 2ε | ε | ε |

| (1 2) | ε | 1 – 2ε | ε | |

| (2 2) | ε | ε | 1 – 2ε | |

- Refer to ‘Methods' section for the definitions of ε1, ε2, ε and for the above models except Sobel's general model and Scheet's allelic model. The definitions of ε1, ε3 and ε4 of Sobel's general model are as following:

- ε1 = 2 Pr(observe homozygote | true is heterozygote).

- ε3 = Pr(observed genotype = i | true genotype = j: i ≠ j, i, j ∈ {(1 1), (2 2)}).

- ε4 = Pr(observe heterozygote | true is homozygote).

The definitions of ε and ε∗ of Scheet's allelic model are as following: ε = Pr (observe heterozygote | true is homozygote).

ε∗ = 2 Pr(observe homozygote | true is heterozygote.

Similar to that in Zou and Zhao [15], we have

C1 = Pr(O = (1 1)) = [(1 – ∊1)p1 + ∊2p2]2

C2 = Pr(O = (1 2)) = 2[(1 – ∊1)p1 + ∊2p2][∊1p1 + (1 – ∊2)p2]

C3 = Pr(O = (2 2) = [∊1p1 + (1 – ∊2)p2]2.

As shown in the Supplementary Material (see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000181153), under the above error model, the only way to estimate error rates is to assume that ∊1 equals to ∊2 and that the allele frequencies are fixed (known). To estimate both allele frequencies and error rates, any model can contain at most one error rate ∊, because, as stated above, there are only two degrees of freedom from the observed data. In the following, we investigate the identifiability of parameters (p1, ∊) under such a simplified model.

Under the allelic model, if we ignore the quadratic terms (which may be reasonable if we assume that the error rate is low) and let ∊ = ∊1 = ∊2, we have a new model, termed the simplified allelic model. The genotype penetrances of this model are shown in table 1.

Note that other types of error models have been described in the literature [4, 34, 57] as well. With the same notation (refer to the note of table 1) as in Sobel et al. [4], we describe the genotype penetrances of Sobel's general models in table 1 for biallelic genotype data. When ∊3 = 0, Sobel's general model degenerates into Scheet's allelic model [54], whose penetrances are also shown in table 1. Both models have non-identifiable parameters because the numbers of parameters are more than two. We further simplify these two models by including only one error rate, and the resultant model is the simplified allelic model, as shown in table 1. In the following, we focus only on the simplified allelic model.

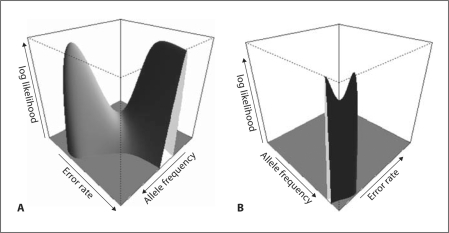

As shown in the Supplementary Material, the parameters of the simplified allelic model are not identifiable. As a consequence, the maximum likelihood estimate (MLE) of the parameters, p1 and ∊, may not be unique. For example, if the observed numbers of genotypes (1 1), (1 2), and (2 2) are 300, 600, and 100, the estimates ( and ) of (p1, ∊) give identical genotype distributions. Consequently, these two parameter sets maximize the log-likelihood function with identical value, 300 × log(0.3) + 600 × log(0.6) + 100 × log(0.1) (less a constant of log(1,000!) – log(300!) – log(600!) – log(100!)). Figure 1A shows the log-likelihood surface for this example. However, if we have the constraint that ∊ ∈ [0, 1/2], both parameters p1 and ∊ of the simplified allelic model are identifiable (see details in the Supplementary Material).

Fig. 1.

The log-likelihood functions of the simplified allelic model (A) and the homoheterozygote model (B). For the simplified allelic model, the function (less a constant of log(1,000!) – log(300!) – log(600!) – log(100!)) is plotted only for the values greater than or equal to −1,000, assuming observations n1 = 300, n2 = 600, and n3 = 100. For the homo-heterozygote model, the function (less a constant of log(1,000!) – log(810!) – log(180!) – log(10!)) is plotted only for the values greater than or equal to −530, assuming observations n1 = 810, n2 = 180, and n3 = 10.

The second model, the homo-heterozygote model, can be expressed as

∊ = Pr(observe homozygote ∣ true is heterozygote)

= Pr(observe heterozygote ∣ true is homozygote)

0 = Pr(O = (1 1) ∣ T = (2 2)) = Pr(O) = (2 2) ∣ T = (1 1)).

Its penetrances are shown in table 1. A similar but more complicated model for nuclear-family data was introduced by Douglas et al. [58]. We can see from the Supplementary Material that the parameters of the homo-heterozygote model are not identifiable. It is not straightforward to make the model parameters identifiable by putting constraints on the parameter space, as we do for the simplified allelic model.

The allelic model described above assumes that errors are introduced randomly and independently into alleles. When assuming that genotyping errors are introduced randomly and independently into genotypes, we have the following genotypic error model

∊ = Pr(observed genotype = i ∣ true genotype = j: i ≠ j, i, j ∈ {(1 1), (1 2), (2 2)}).

Its penetrances are shown in table 1. We can see from the Supplementary Material that the parameters of the genotypic model are not identifiable. However, with the constraint ∊ ∈ [0, 1/3] on the parameter space where the model parameters become identifiable.

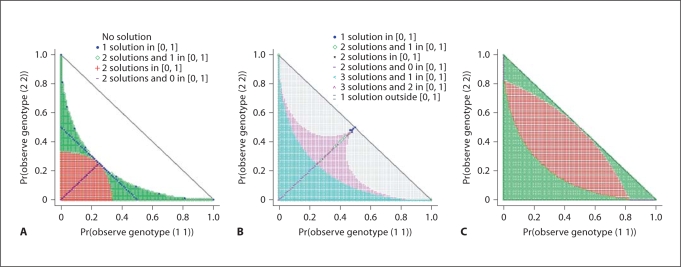

Under any of the aforementioned error models, the genotyping error rates, as well as the allele frequencies, are functions of C1 and C3 (actually, functions of any two of C1, C2, and C3). Plotted in figure 2A–C are respectively the distributions of solutions of error rates under the simplified allelic model, the homo-heterozygote model, and the genotypic model, for possible values of (C1, C3). It can be seen that for most values (about 65%) of (C1, C3), the simplified allelic model does not have a real number solution for the error rate (although complex solutions exist, they do not qualify as an error rate); for almost one-half (about 46.2%) of the (C1, C3) values, the homo-heterozygote model does not have a solution within [0, 1] for the error rate; whereas for only a small fraction (about 0.67%) of the (C1, C3) values, the genotypic model does not have a solution in [0, 1] for the error rate. In the following, we evaluate the performance of only the two models with identifiable parameters: the simplified allelic model and the genotypic model.

Fig. 2.

The solutions for error rates, as functions of C1 and C3, under the following models: (A) the simplified allelic model, (B) the homo-heterozygote model, and (C) the genotypic model with different values of C1 and C3 as defined in the text. Both (A) and (C) have the same legends, which are shown in (A) only.

We conducted a simulation study by setting the major allele frequency (MAF) as 0.6; the error rate as 0.06, 0.02, and 0; and the sample size as 1,000. We assumed HWE in the models. We also investigated the influences of departure from HWE on the estimates of error rate and allele frequency. We followed a model of departure from HWE in the literature [59] as described below

pkl = (1 – f)pkpl + 2δk lfpk, k, l = 1, 2

where pkl is the frequency of genotype (k l), δkk = 1 and δkl = 0 (k ≠ l), and f is the inbreeding coefficient or fixation index indicating the magnitude of departure from HWE. We also applied the genotypic model and the simplified allelic model to one real data set from the HapMap project [60] to evaluate the performance of these models. We used the genotype data from 44 Japanese individuals on chromosome 17 that were released in October 2005. After eliminating the SNPs with missing genotypes and those which were homozygous, a total of 14,803 out of the original 24,336 SNPs were left and were used in this study.

was employed for all the hypothesis testing. P values reported are two-sided.

Results

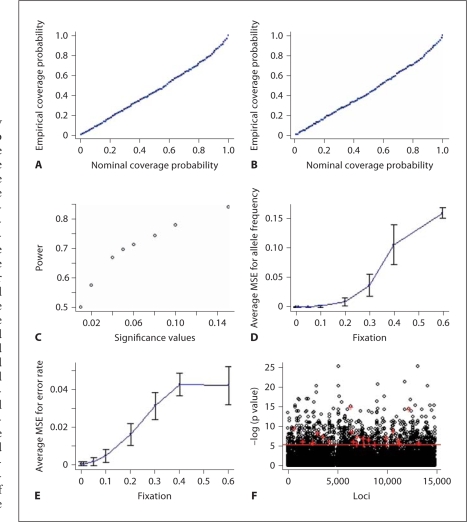

The simulation results are summarized in table 2, which shows that the genotypic model works well and, in general, better than the simplified allelic model. Figures 3A–E reveal important properties of the genotypic model through this simulation study on the basis of 1,000 simulated datasets with a major allele frequency of 0.6, an error rate of 0.06, and a sample size of 1,000. Shown in figures 3A and B are the empirical coverage probability of the confidence intervals for the estimates of allele frequency and error rate (similar patterns can be observed for an error rate of 0.02). Those two plots suggest that the estimates of parameters and standard errors are reliable. For the simplified allelic model, the coverage probability of the confidence intervals for the estimate of allele frequency is similar to figure 3A; however, the coverage probability of the confidence intervals for the estimate of error rate is not as good as figure 3B. Figure 3C shows the power under different significance levels. Both the power and type I error rate from the simplified allelic model are lower than those from the genotypic model (data not shown). Figures 3D and E display the effects of departure from HWE on the genotypic model. As expected, the estimation accuracy depends on the magnitude of departure from HWE: the further away from HWE, the lower the accuracy. However, we observe that the estimation is not very sensitive to departure from HWE.

Table 2.

Simulation results

| Null model |

Alternative model |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error rate | MAF | Error rate | MAF | Error rate | MAF | |

| True | 0 | 0.6 | 0.02 | 0.6 | 0.06 | 0.6 |

| Genotypic model | ||||||

| Mean | 0.011 | 0.604 | 0.023 | 0.601 | 0.058 | 0.600 |

| Median | 0.001 | 0.603 | 0.020 | 0.601 | 0.059 | 0.598 |

| Bias | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.002 | 0.000 |

| Standard deviation | 0.015 | 0.012 | 0.021 | 0.014 | 0.027 | 0.016 |

| Mean of standard error estimates | 0.022 | 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.012 | 0.023 | 0.014 |

| CP | 0.949 | 0.908 | 0.950 | 0.914 | 0.905 | 0.900 |

| Power | 0.051∗ | 0.194 | 0.669 | |||

| Simplified allelic model | ||||||

| Mean | 0.038 | 0.610 | 0.052 | 0.610 | 0.077 | 0.610 |

| Median | 0.030 | 0.607 | 0.039 | 0.606 | 0.054 | 0.601 |

| Bias | 0.038 | 0.010 | 0.032 | 0.010 | 0.017 | 0.010 |

| Standard deviation | 0.032 | 0.022 | 0.044 | 0.026 | 0.063 | 0.035 |

| Mean of standard error estimates | 0.051 | 0.012 | 0.052 | 0.012 | 0.053 | 0.013 |

| CP | 0.967 | 0.871 | 0.936 | 0.866 | 0.902 | 0.851 |

| Power | 0.033∗ | 0.087 | 0.159 | |||

MAF is the major allele frequency. CP is the coverage probability of the 95% confidence interval for the parameters. Power pertains to the 0.05 level Wald test of H0: error rate is 0. Each entry is based on 1,000 data sets, each of sample size 1,000.

Is actually type I error rate.

Fig. 3.

The results of the simulation study on the genotypic model and application to the HapMap data: (A) empirical coverage of the confidence intervals for the estimate of allele frequency, (B) empirical coverage of the confidence intervals for the estimate of the error rate, (C) the power for detecting genotyping errors under different significance levels, (D) the impact of departure from HWE on the estimate of allele frequency, (E) the impact of departure from HWE on the estimate of the error rate, and (F) the negative log-transformed (base 10) p values of error rates on the HapMap Japanese data. The p values were from the model with higher likelihood (between the simplified allelic model and the genotypic model) and were plotted against the physical order of SNPs. The red pluses indicate the negative log-transformed p values of the finally selected SNPs with the selection procedure described in the text. The red horizontal line indicates the negative log-transformed (base 10) value of 0.05/14,803. In the simulation study, 1,000 data sets were simulated, assuming a major allele frequency of 0.6, an error rate of 0.06, and a sample size of 1,000.

We applied both the genotypic model and the simplified allelic model to the aforementioned HapMap data. At each SNP, the p value (for testing the hypothesis that the error rate is 0) is reported from the model with a higher likelihood value. The distributions of the estimated error rates have a high spike around zero, and drop quickly at points away from zero. The summary statistics may reflect the distribution. For example, the mean, median, and standard deviation of the estimated error rates under the genotypic model are 0.024, 1.831 × 10–7, and 0.048, respectively. Figure 3F shows the (base 10) log-transformed p values for the error rate at each locus after eliminating markers with missing genotypes and which are homozygotes. None of the models listed in table 1 can distinguish between genotyping error and departure from HWE (i.e., Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium from non-genotyping error causes, such as nonrandom mating). Even with very small p values, some of the SNP configurations may be real and due to local linked selection, instead of genotyping errors. SNPs that are close to each other on the chromosome usually have a high level of linkage disequilibrium between them. Consequently, these SNPs may have a similar level of departure from HWE if it is due to local selection. In order to get rid of these SNPs, we chose the SNPs that had p values less than 0.05/14,803 (14,803 is the number of SNPs used in this study and a Bonferroni correction is applied) and did not have such SNPs (i.e. SNPs with p values less than 0.05/14,803) in their neighborhood (we chose the neighborhood as the region containing 50 SNPs on each side). Finally we identified 22 SNPs, which may have genotyping errors and are indicated with the red plus in figure 3F. The p values of Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test for the 22 SNPs are in the range of 0.008–0.236. This is expected because for the HapMap data, the quality control criteria for Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium is that p value ≥ 0.001 (http://www.hapmap.org/downloads/data-handling_protocols.html). The p values presented in figure 3F are not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

The error models considered in this article have been used for pedigree data. Note that all of them can be derived from the general model proposed by Sobel et al. [4]. Although some work has been conducted to detect genotyping errors for pedigree data, little work has been done for unrelated population data. In this article, we consider the issue of genotyping error detection for unrelated population data by investigating some error models originally proposed for pedigree data. In particular, assuming HWE (for the underlying data without errors), both the genotypic model and the simplified allelic model can detect genotyping errors. This holds promise for using statistical methods to detect genotyping errors without having to genotype relatives or resample replicates.

Detecting genotyping errors on the basis of these error models differs from detection based on testing HWE in two main ways. First, the HWE test is only a hypothesis test, whereas the error models also provide estimates of the error rates. Second, we can obtain estimates of the true allele frequencies by using these error models, which is very important in practice.

We need to put some constraints on the parameter space in order to make the model parameters (i.e., the simplified allelic and genotypic models) identifiable. The simplified allelic model becomes identifiable when the error rate is at most 0.5, and the genotypic model becomes identifiable when the error rate is at most 1/3 when . We know that in genotyping, the labeling is arbitrary, i.e., which of the two alleles is assigned the value of ‘1’ (using ‘1’ and ‘2’ for the two alleles) is arbitrary. For the simplified allelic model, if the error rate ∊ is higher than 0.5, we can simply switch the label, and the error rate becomes 1 – ∊, which is smaller than 0.5. The extreme case is that ∊ = 1, i.e., allele 1 is typed as allele 2 and allele 2 is typed as allele 1 completely, which implies perfect genotyping (i.e., ∊ = 0 with switched labels). Therefore, the simplified allelic model has a reasonable identifiability condition in consideration of the arbitrary labeling in genotyping. For genotypic model, there exist two real solutions to the error rate in the region (C1 – C3)2 + 4(C1 + C3) > 4 and C1 + C3 ≤1, with one larger than 1 and the other one in [0, 1/3]. Therefore restricting ∊ ∈[1/3, 1] does not work on the entire parameter space. In addition, it is not plausible to have error rate larger than 1/3 in practice.

Our simulation study shows that, in general, the genotypic model performs better than the simplified allelic model in terms of parameter estimates and sensitivity to initial values. Both models perform a little better in the case of ∊ > 0 than in the case of ∊ = 0. This may be because ∊ is on the boundary of the parameter space when ∊ = 0. We also observed that the sample size has a larger effect on type II error, and thus power, than on type I error. When the sample sizes are small, the models may have low power to detect genotyping errors. However, once an error is detected, it is highly possible that the error will be observed. With the fixed sample sizes in our simulation study, the power of detecting small error rates is relatively low, which is expected and common in genetic studies. We always need to increase sample size to detect small effects.

When choosing among the models that we present to practice genotyping error detection, we may make our decision on the basis of knowledge from both the experiment and the data. For example, we may take into consideration the genotyping technique used (e.g., allele-specific technique), the calling software, and the fitting of the models to the data. We found in our simulation study that for the region shown as ‘no solution’ in figure 2A (), the likelihood values of the genotypic model were uniformly higher than those of the simplified allelic model (data not shown). For the region the likelihood of the simplified allelic model is always larger than that of the genotypic model. Therefore, these two models may complement each other in practice.

It is commonly known that genotyping errors exist in most genotype data and have substantial effects on biological conclusions. However, they are neglected most of the time, especially for unrelated population data. As stated in Sobel et al., ‘Marker genotyping errors are the skeleton in the closet of statistical genetics’ [4]. The present work intends to estimate error rates for the genotype data, so researchers can base their analysis on the estimated error rates to increase power and decrease bias without genotyping family members or replicates [13, 15, 48]. Of note, duplicate typing directly captures consistency rather than accuracy. This has been noticed by other researchers as well [4, 61].

As in many other works in the literature, we focused on a single biallelic marker, which may be too simplified in practice. To have a more flexible model for more practical scenarios, we should consider more markers simultaneously and take into account linkage disequilibrium information, as suggested by Sobel et al. [4] and Scheet and Stephens [54]. Another future direction is to relax the assumption of HWE where the influence of departure from HWE can be disentangled from genotyping error.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the grants GM59507, GM57672 (HZ), P30DK056336, and GM081488 (NL) from the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank three anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions that improved the manuscript.

References

- 1.Brush G, Almasy L. Pedigree and genotype errors in the Framingham heart study. BMC Genet. 2003;4(suppl 1):S41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-4-S1-S41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukhopadhyay N, Buxbaum SG, Weeks DE. Comparative study of multipoint methods for genotype error detection. Hum Hered. 2004;58:175–189. doi: 10.1159/000083545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoffman JI, Amos W. Microsatellite genotyping errors: Detection approaches, common sources and consequences for paternal exclusion. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:599–612. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sobel E, Papp JC, Lange K. Detection and integration of genotyping errors in statistical genetics. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:496–508. doi: 10.1086/338920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pompanon F, Bonin A, Bellemain E, Taberlet P. Genotyping errors: Causes, consequences and solutions. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:847–859. doi: 10.1038/nrg1707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonin A, Bellemain E, Bronken Eidesen P, Pompanon F, Brochmann C, Taberlet P. How to track and assess genotyping errors in population genetics studies. Mol Ecol. 2004;13:3261–3273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon D, Finch SJ. Factors affecting statistical power in the detection of genetic association. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1408–1418. doi: 10.1172/JCI24756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gordon D, Haynes C, Yang Y, Kramer PL, Finch SJ. Linear trend tests for case-control genetic association that incorporate random phenotype and genotype misclassification error. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31:853–870. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cardon LR, Abecasis GR, Cherny SS. The effect of genotype error on the power to detect linkage and association with quantitative traits. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:310–310. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cardon LR. The impact of genotyping error on family-based analysis of quantitative traits. Eur J Hum Genet. 2001;9:130–134. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirk KM, Cardon LR. The impact of genotyping error on haplotype reconstruction and frequency estimation. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:616–622. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell AA, Cutler DJ, Chakravarti A. Undetected genotyping errors cause apparent overtransmission of common alleles in the transmission/disequilibrium test. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:598–610. doi: 10.1086/368203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rice KM, Holmans P. Allowing for genotyping error in analysis of unmatched case-control studies. Ann Hum Genet. 2003;67:165–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zou G, Pan D, Zhao H. Genotyping error detection through tightly linked markers. Genetics. 2003;164:1161–1173. doi: 10.1093/genetics/164.3.1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zou G, Zhao H. Haplotype frequency estimation in the presence of genotyping errors. Hum Hered. 2003;56:131–138. doi: 10.1159/000073741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gordon D, Haynes C, Johnnidis C, Patel SB, Bowcock AM, Ott J. A transmission disequilibrium test for general pedigrees that is robust to the presence of random genotyping errors and any number of untyped parents. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:752–761. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gordon D, Yang Y, Haynes C, Finch SJ, Mendell NR, Brown AM, Haroutunian V. Increasing power for tests of genetic association in the presence of phenotype and/or genotype error by use of double-sampling. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1085. Article26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang SJ, Finch SJ, Haynes C, Gordon D. Quantifying the percent increase in minimum sample size for snp genotyping errors in genetic model-based association studies. Hum Hered. 2004;58:139–144. doi: 10.1159/000083540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang S, Sha Q, Chen H, Dong J, Jiang R. Impact of genotyping errors on type i error rate of the haplotype-sharing transmission/disequilibrium test (hs-tdt) – reply. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:591–593. doi: 10.1086/382287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zou G, Zhao H. The impacts of errors in individual genotyping and DNA pooling on association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;26:1–10. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji F, Yang Y, Haynes C, Finch SJ, Gordon D. Computing asymptotic power and sample size for case-control genetic association studies in the presence of phenotype and/or genotype misclassification errors. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2005;4 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1184. Article37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moskvina V, Craddock N, Holmans P, Owen M, O'Donovan M. Minor genotyping error can result in substantial elevation in type i error rate in haplotype based case control analysis. Am J Med Gen Part B-Neuropsychiatric Genet. 2005;138B:19–19. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seaman SR, Holmans P. Effect of genotyping error on type-i error rate of affected sib pair studies with genotyped parents. Hum Hered. 2005;59:157–164. doi: 10.1159/000085939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moskvina V, Craddock N, Holmans P, Owen MJ, O'Donovan MC. Effects of differential genotyping error rate on the type I error probability of case-control studies. Hum Hered. 2006;61:55–64. doi: 10.1159/000092553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lai R, Zhang H, Yang Y. Repeated measurement sampling in genetic association analysis with genotyping errors. Genet Epidemiol. 2007;31:143–153. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akey JM, Zhang K, Xiong M, Doris P, Jin L. The effect that genotyping errors have on the robustness of common linkage-disequilibrium measures. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:1447–1456. doi: 10.1086/320607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein DR, Zhao H, Speed TP. The effects of genotyping errors and interference on estimation of genetic distance. Hum Hered. 1997;47:86–100. doi: 10.1159/000154396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tung L, Gordon D, Finch SJ. The impact of genotype misclassification errors on the power to detect a gene-environment interaction using cox proportional hazards modeling. Hum Hered. 2007;63:101–110. doi: 10.1159/000099182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Becker T, Knapp M. Comment on ‘The impact of genotyping error on haplotype reconstruction and frequency estimation’. Eur J Hum Genet. 2003;11:637. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker T, Valentonyte R, Croucher PJ, Strauch K, Schreiber S, Hampe J, Knapp M. Identification of probable genotyping errors by consideration of haplotypes. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:450–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Knapp M, Becker T. Impact of genotyping errors on type I error rate of the haplotype-sharing transmission/disequilibrium test (hs-tdt) Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:589–591. doi: 10.1086/382287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niu TH. Algorithms for inferring haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2004;27:334–347. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Quade SRE, Elston RC, Goddard KAB. Estimating haplotype frequencies in pooled DNA samples when there is genotyping error. BMC Genet. 2005:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-6-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon D, Finch SJ, Nothnagel M, Ott J. Power and sample size calculations for case-control genetic association tests when errors are present: Application to single nucleotide polymorphisms. Hum Hered. 2002;54:22–33. doi: 10.1159/000066696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levenstien MA, Ott J, Gordon D. Are molecular haplotypes worth the time and expense? A cost-effective method for applying molecular haplotypes. PLoS Genet. 2006:2. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heid IM, Lamina C, Bongardt F, Fischer G, Klopp N, Huth C, Kuchenhoff H, Kronenberg F, Wichmann HE, Illig T. [How about the uncertainty in the haplotypes in the population-based kora studies?] Gesundheitswesen. 2005;67(suppl 1):S132–S136. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-858253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang SJ, Gordon D, Finch SJ. What SNP genotyping errors are most costly for genetic association studies? Genet Epidemiol. 2004;26:132–141. doi: 10.1002/gepi.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Callen DF, Thompson AD, Shen Y, Phillips HA, Richards RI, Mulley JC, Sutherland GR. Incidence and origin of ‘null’ alleles in the (AC)n microsatellite markers. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:922–927. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taberlet P, Griffin S, Goossens B, Questiau S, Manceau V, Escaravage N, Waits LP, Bouvet J. Reliable genotyping of samples with very low DNA quantities using pcr. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:3189–3194. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.16.3189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brownstein MJ, Carpten JD, Smith JR. Modulation of non-templated nucleotide addition by taq DNA polymerase: Primer modifications that facilitate genotyping. Biotechniques. 1996;20:1004–1006. doi: 10.2144/96206st01. 1008–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rabbee N, Speed TP. A genotype calling algorithm for affymetrix SNP arrays. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:7–12. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hosking L, Lumsden S, Lewis K, Yeo A, McCarthy L, Bansal A, Riley J, Purvis I, Xu CF. Detection of genotyping errors by Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2004;12:395–399. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McPeek MS, Sun L. Statistical tests for detection of misspecified relationships by use of genome-screen data. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1076–1094. doi: 10.1086/302800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'Connell JR, Weeks DE. Pedcheck: A program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Broman KW, Wu H, Sen S, Churchill GA. R/qtl: QTL mapping in experimental crosses. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:889–890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marshall TC, Slate J, Kruuk LE, Pemberton JM. Statistical confidence for likelihood-based paternity inference in natural populations. Mol Ecol. 1998;7:639–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.1998.00374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller CR, Joyce P, Waits LP. Assessing allelic dropout and genotype reliability using maximum likelihood. Genetics. 2002;160:357–366. doi: 10.1093/genetics/160.1.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gordon D, Ott J. Assessment and management of single nucleotide polymorphism genotype errors in genetic association analysis. Pac Symp Biocomput. 2001:18–29. doi: 10.1142/9789814447362_0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huebner C, Petermann I, Browning BL, Shelling AN, Ferguson LR. Triallelic single nucleotide polymorphisms and genotyping error in genetic epidemiology studies: Mdr1 (abcb1) g2677/t/a as an example. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:1185–1192. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saunders IW, Brohede J, Hannan GN. Estimating genotyping error rates from mendelian errors in SNP array genotypes and their impact on inference. Genomics. 2007;90:291–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gordon D, Heath SC, Ott J. True pedigree errors more frequent than apparent errors for single nucleotide polymorphisms. Hum Hered. 1999;49:65–70. doi: 10.1159/000022846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheng KF, Chen JH. A simple and robust TDT-type test against genotyping error with error rates varying across families. Hum Hered. 2007;64:114–122. doi: 10.1159/000101963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng KF. Analysis of case-only studies accounting for genotyping error. Ann Hum Genet. 2007;71:238–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scheet P, Stephens M. A fast and flexible statistical model for large-scale population genotype data: Applications to inferring missing genotypes and haplotypic phase. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78:629–644. doi: 10.1086/502802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casella G, Berger LR. Statistical inference. ed 2. Duxbury Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gordon D, Heath SC, Liu X, Ott J. A transmission/disequilibrium test that allows for genotyping errors in the analysis of single-nucleotide polymorphism data. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:371–380. doi: 10.1086/321981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scheet P, Stephens M: Patterns of linkage disequilibrium reveal genotyping errors and copy number polymorphisms: Proceeding of the American Society of Human Genetics 56th Annual Meeting. New Orleans, Louisiana, 2006.

- 58.Douglas JA, Skol AD, Boehnke M. Probability of detection of genotyping errors and mutations as inheritance inconsistencies in nuclear-family data. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:487–495. doi: 10.1086/338919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Weir BS. Genetic data analysis II. Sunderland: Sinauer; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 60.The International HapMap Consortium The international hapmap project. Nature. 2003;426:789–796. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tintle NL, Gordon D, McMahon FJ, Finch SJ. Using duplicate genotyped data in genetic analyses: Testing association and estimating error rates. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2007;6 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1251. Article 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material