Abstract

The hypothesis that lipid rafts exist in plasma membranes and have crucial biological functions remains controversial. The lateral heterogeneity of proteins in the plasma membrane is undisputed, but the contribution of cholesterol-dependent lipid assemblies to this complex, non-random organization promotes vigorous debate. In the light of recent studies with model membranes, computational modelling and innovative cell biology, I propose an updated model of lipid rafts that readily accommodates diverse views on plasma-membrane micro-organization.

A widely accepted hypothesis in contemporary cell biology is that freely diffusing, stable, lateral assemblies of sphingolipids and cholesterol, which are termed lipid rafts1-3, constitute an important organizing principle for the plasma membrane. The basic concept is that lipid rafts can facilitate selective protein–protein interactions by selectively excluding or including proteins. This lipid-based sorting mechanism has been widely implicated in the assembly of transient signalling platforms and more permanent structures such as the immunological synapse, as well as in the sorting of proteins for entry into specific exocytic and endocytic trafficking pathways1-3. Despite the undoubted theoretical utility of lipid rafts to many cell biological processes, the basic hypothesis that stable lipid rafts exist at all in biological membranes is under intense scrutiny4,5. This is partly because lipid rafts, if they exist in resting cell membranes, are too small to be resolved by fluorescent microscopy and have no defined ultrastructure; therefore, proving their existence is problematic.

This article will consider the biophysical properties of model membranes that underpin the lipid raft hypothesis, and the limitations of the biochemical approaches that have been used to study rafts in biological membranes that largely account for the current debate on the hypothesis mentioned above. After examining the challenges that are involved in correlating observations, which have been made in model and cellular membranes, I focus on synthesizing recent data on the size of lipid domains in model membranes with observations that have been obtained by imaging intact plasma membranes. These imaging approaches include single particle tracking (SPT), single fluorophore video tracking (SFVT), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), homo-FRET and electron microscopy (EM). On the one hand, these studies challenge the simplistic null hypothesis that lipid-based assemblies, such as lipid rafts, do not exist in biological membranes. On the other hand, it is timely to reconsider the raft hypothesis in the light of these new data because the consensus model that emerges is more complex than a simplistic notion of stable, freely diffusing lipid rafts. Some intriguing new questions about the structure and function of lipid rafts in the plasma membrane, which are posed by this revised raft model, will be discussed.

Biophysics and model membranes

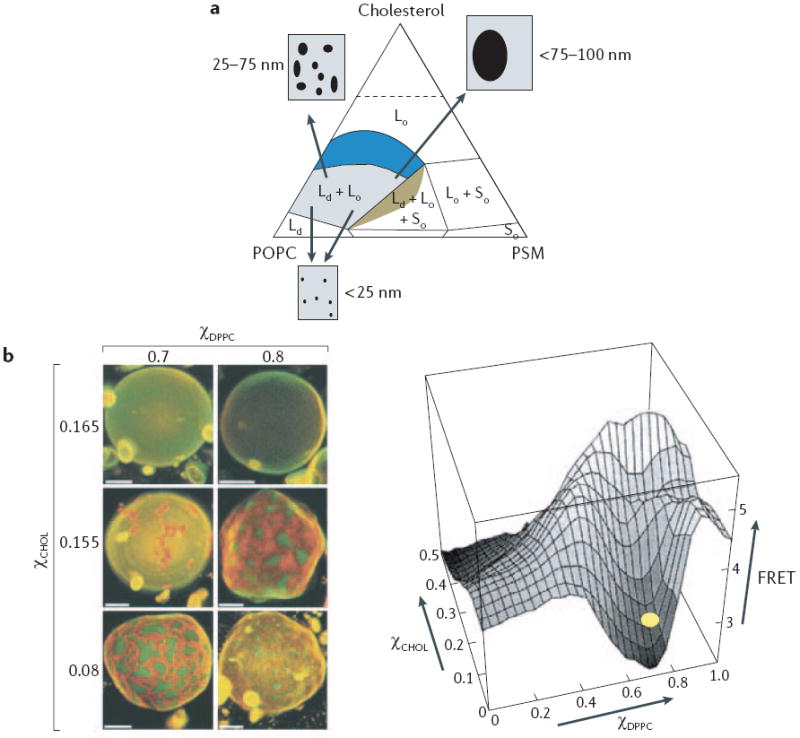

Although the plasma membrane is a complex organelle, its basic structure consists of a phospholipid bilayer. Some insights into the behaviour of this basic structure might then be anticipated by analysing model membranes that consist of simple, hydrated phospholipid bilayers. An important property of such a model membrane is revealed as the temperature of the bilayer is progressively increased. At a temperature that is characteristic of the particular lipid species, the phospholipids undergo a phase transition from a solid ordered, or gel, phase (So) to a liquid disordered phase (Ld). The lateral mobility of the lipids, which is highly restricted in the So phase, increases, and the acyl-side chains become disordered and no longer pack together tightly in rigid straight conformations. If the membrane also contains sufficient cholesterol, a third phase (liquid ordered (Lo)) is possible. The Lo phase is characterized by a high degree of acyl-chain ordering, which is typical of the So phase, but with the translational disorder (or increased lateral mobility) that is characteristic of the Ld phase, such that lipid diffusion in the Lo phase is only two- to three-fold slower than in the Ld phase. Precisely how cholesterol drives the formation of the Lo phase remains unclear (BOX 1). Importantly, in membranes that comprise appropriate mixtures of sphingomyelin, unsaturated phospholipids and cholesterol, Lo and Ld phases can co-exist6,7 (FIG. 1).

Box 1 How does cholesterol drive domain formation in membranes?

The presence of cholesterol and saturated phospholipids, such as sphingomyelin, is crucial to observe phase co-existence. However, what does the cholesterol actually do, and what is the structure and size of the two co-existing phases? Cholesterol has a condensing effect on phospholipids. Therefore, a mixture of cholesterol and phospholipid occupies a smaller area than expected from the sum of the constituents. One explanation is that cholesterol forms reversible, condensed complexes of defined stoichiometry with phospholipids50-51. Another possibility is that the head groups of the phospholipids shield hydrophobic cholesterol from contact with the membrane–water interface and therefore function as umbrellas52. In performing this umbrella function, the side chains of the phospholipids need to become more ordered to allow closer packing and crowding of the lipid head groups. A third and particularly interesting possibility is shown by computational modelling of the molecular interactions in a ternary mixture of cholesterol, 1,2-dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC) and sphingomyelin53-54. As the simulations evolve, cholesterol preferentially localizes at the interface between sphingomyelin-enriched and DOPC-enriched regions, with the saturated sphingomyelin acyl chains packing against the smooth α-face of cholesterol, and the disordered acyl chains of DOPC packing more easily against the opposite β-face, which is rougher because of protruding methyl groups53. The intriguing aspect of these simulations is the potential insight that can be given into the very early molecular interactions that lead to domains. Although the simulations were time-limited, formation of small nanoscale domains was observed. Moreover, the domains remained small and were not increasing in size at the end of the simulation (currently to 200 ns)53. These results show that the domains that form spontaneously are small and curvilinear, and that cholesterol might have an important role in reducing the line tension between liquid ordered (Lo) and liquid disordered (Ld) domains53.

Figure 1. Liquid-ordered domains in model membranes.

a Phase diagram at 23°C for ternary mixtures of cholesterol, sphingomyelin (PSM) and l-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine (POPC). Each vertex of the diagram corresponds to a 100% content of each lipid. Coloured regions represent membrane compositions that can form a liquid disordered (Ld) phase. Within the region of liquid ordered (Lo)–Ld co-existence (blue), varying the cholesterol percentages from ~10% to 35% progressively increases the size of Lo domains that are detected by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) imaging or standard microscopy7. It is important to note that phase diagrams such as this are crucially dependent on temperature, although an extensive area of Lo–Ld phase co-existence is present at 37°C(see REFS 3,6). b Macroscopic domain formation in giant unilamellar vesicles that are composed of cholesterol, 1,2-dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) and 1,2-dioleoylphosphatidylcholine (DOPC) and visualized using dyes that preferentially partition into Lo domains (orange) and Ld domains (green). When the cholesterol percentage (χCHOL) is >16%, macroscopic domain formation is no longer seen, but nanodomain formation is still detectable as a loss of a FRET signal between two probes that preferentially partition into Lo and Ld domains. The yellow oval marks the approximate composition of the top row of vesicles. Scale bar = 5μm. χDPPC = DPPC content as a fraction of DPPC and DOPC. Part a is reproduced with permission from REF. 7 © (2005) Elsevier; part b is reproduced with permission from REF. 13 © (2001) The Biophysical Society.

Lipid rafts in biological membranes are postulated to be microdomains with a lipid structure that is equivalent to the Lo phase of model membranes, and to be surrounded by a contiguous ‘sea’ of membrane with a lipid structure that is equivalent to the Ld phase of model membranes. The abbreviated term ‘Lo domain’ captures these concepts and will be used hereafter in this article. The crucial role of cholesterol in allowing Lo phase formation therefore provides the theoretical basis for cholesterol-depletion experiments that are extensively used to disrupt the Lo structure of lipid rafts in living cells. However, it is important to realize that drugs such as β-methyl-cyclodextrin that are used to extract cholesterol from the plasma membrane also have other effects (BOX 2). Furthermore, a comment is needed here on another biochemical technique that is widely used to study lipid rafts. Detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fractions that are prepared from model membranes and cell membranes are enriched in cholesterol and sphingomyelin, and contain a subset of lipid-anchored and integral plasma-membrane proteins8-10. These observations, among other things, have led to the assumption that Lo domains, lipid rafts and DRMs can be considered as synonymous terms (BOX 2). This assumption has led to an ever-increasing number of proteins being assigned to lipid rafts based solely on their DRM association, and has prompted a series of valid, crucial questions to be asked of the lipid-raft hypothesis4,5 (BOX 2).

Box 2 Limitations of biochemical approaches to study lipid rafts in biological membranes

A detergent-resistant membrane (DRM) fraction is prepared by solubilizing cell membranes in Triton-X100 at 4°C and purifying an insoluble fraction by flotation on a density gradient. A DRM fraction is enriched in cholesterol and sphingomyelin and contains >240 proteins, including glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins, caveolin and a subset of transmembrane proteins8-10,55. The interpretation of DRM experiments is predicated on the assumption that liquid ordered (Lo) domains that exist in intact membranes at 37°C and their associated proteins are faithfully purified by cold-detergent extraction8-10. It is clear, however, that the association of a protein with a DRM fraction should not be considered sole evidence that a protein is associated with Lo domains in intact cells. The effects of detergents on membranes are much too complex to draw substantive conclusions about the nanoscale localization of a given protein on native membrane56. For example, detergents can create domains, cause mixing of domains and solubilize proteins and lipids irrespective of their intrinsic affinity for Lo domains56-58. As one of many examples, consider that 30% of GPI–PLAP (placental alkaline phosphatase) partitions into the Lo phase of a unilamellar model membrane as detected by direct imaging of intact vesicles, whereas >95% is recovered in a DRM fraction prepared from the same vesicles20. This topic has been the subject of an excellent recent review56 and will not be considered further. Precisely what association with a DRM fraction might mean, and whether it is a useful parameter in an experimental context for any given protein in which mutations or activation status alter the extent of DRM association, is beyond the scope of this article, but has been considered elsewhere23-56. The bottom line is that there is no substitute for using an imaging technique with nanoscale resolution to visualize intact plasma membrane to provide compelling evidence for non-random protein clustering that is consistent with raft localization.

Cholesterol depletion using agents such as β-methyl-cyclodextrin has been used extensively in model systems. When applied to cells, these cholesterol-binding drugs have effects other than their ability to extract cholesterol from membranes and disrupt Lo domains. Perturbation of the actin cytoskeleton59 and inhibition of clathrin-mediated endocytosis are probably directly related to cholesterol depletion per se60-62, but β-methyl-cyclodextrin has other effects that are unrelated to cholesterol depletion, such as global inhibition of the lateral mobility of plasma-membrane proteins, irrespective of their putative association with Lo domains63. The latter effects are not seen with cholesterol depletion using statins47,63,64. Failure to appreciate such phenomena can lead to over-interpretation or misinterpretation of experimental results.

Lo domains in model membranes

In model membranes, macroscopic separation of Lo and Ld phases into large (>200 nm) domains is clearly visible using fluorescent dyes that partition differentially into the two phases (FIG. 1). These large Lo domains are not seen in native cell membranes. However, the use of techniques other than light microscopy11 (which is limited by diffraction and has a spatial resolution of >200 nm) to probe shorter length scales that are biologically relevant provides ample evidence for much smaller Lo domains. For example, donor-quenching FRET analysis shows nanoscale domain formation (~10–40 nm) in lipid bilayers with a similar composition to that of the outer plasma membrane, at the physiologically relevant temperature of 37°C, when macroscopic phase separation is not evident12. Similarly, Lo nanodomains can be detected by FRET in regions of a phase diagram in which confocal microscopy indicates only the presence of a single homogenous phase13 (FIG. 1). Domains on length scales of 30–80 nm in a region of Lo and Ld co-existence have also been detected using atomic-force microscopy (AFM)14, deuterium-based nuclear magnetic resonance (2H-NMR) and differential scanning calorimetry15-17, although there is some debate here as to whether these small domains represent true thermodynamic phase separation16,17. The effective local cholesterol concentration might determine Lo domain size; in membranes that show coexistence of Lo and Ld, varying the cholesterol content from ~10% to 35% progressively increases the size of Lo domains from small (<20 nm), through intermediate sizes (20–75 nm) detected by FRET imaging, to larger domains (>100 nm) that are visible by standard microscopy7 (FIG. 1).

A crucial requirement of the raft hypothesis in biological membranes is that these domains can laterally segregate proteins. There is clear evidence for this function in model membranes. Lo–Ld phase separation in model membranes laterally segregates glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins, although the segregation is usually incomplete. For example, ~40% of the GPI-anchored protein THY1 partitions into Lo domains of supported monolayers and unsupported bilayers18,19. Similarly, ~30% of GPI–PLAP (placental alkaline phosphatase) partitions into Lo domains of giant unilamellar vesicles that are imaged using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), although this fraction increases if the GPI–PLAP is crosslinked20. The lateral mobility of GPI–PLAP is 1.4-fold slower than the mobility of free lipids in the model membrane20 — this is an important result because the formation of simple protein clusters would not increase the hydronamic radii of GPI–PLAP complexes sufficiently to retard diffusion. This result therefore implies either nanoscale lipid-domain organization around the GPI–PLAP proteins, or transient interactions with larger Lo domains. In summary, complex lipid–lipid–cholesterol interactions in model membranes with a lipid composition approximating that of the outer plasma membrane spontaneously generate lateral heterogeneity on multiple length scales. The plasma membrane is a much more complex structure than these simple model membranes (BOX 3). However, there is no a priori reason to assume that the basic lipid biochemistry and thermodynamics that operate in model systems are not the same as those that operate in the plasma membrane.

Box 3 Extrapolating from model membranes to the plasma membrane

The plasma membrane is a much more complex structure than a model membrane. Extrapolations of observations made in model systems must take account of some of the important differences between a simple bilayer with a defined lipid composition and the plasma membrane. For example:

The plasma membrane has a much more complex mixture of lipids65, although the general class mixture (unsaturated phospholipid–sphingomyelin–cholesterol) is matched by the more relevant model membranes.

The plasma membrane contains a plethora of lipid-anchored proteins, transmembrane proteins and peripheral membrane proteins.

The plasma membrane is not a static platform and cannot be considered an equilibrated membrane, not least because there is constant internalization and recycling of vesicles through multiple endocytic pathways66.

Kusumi and colleagues have shown that the plasma membrane is compartmentalized by a picket fence of transmembrane proteins that are anchored to the submembrane actin cytoskeleton26,67-69. The fence allows relative free lateral diffusion of lipids within compartments but restricts movement between compartments. One important consequence of the picket fence is that it slows long-range lipid diffusion, because lipids can only undergo hop diffusion between neighbouring compartments as the fence fluctuates. The restriction on lateral diffusion between compartments means that the lipid bilayer is not well-mixed on long-length scales.

Cholesterol is excluded from the immediate vicinity of transmembrane proteins; therefore the local concentration of cholesterol will vary on a nanometer-length scale26,70.

Cells are not simple spheres, and local differences in membrane curvature can have profound effects on lipid sorting71.

Most model membranes have been studied at 23°C rather than 37 °C.

The plasma membrane is an asymmetric bilayer, the composition of the inner membrane is unclear, and the degree to which the two leaflets are coupled remains unknown.

However, despite these complexities the basic matrix remains a lipid bilayer, with the outer leaflet, at least, similar to lipid cholesterol mixtures that have the intrinsic property of self-organization into domains or lipid assemblies on multiple length scales.

Lipid rafts in the intact plasma membrane?

The classic lipid-raft hypothesis postulates that rafts pre-exist in the plasma membrane1,3. Proteins with lipid anchors or transmembrane domains that are able to partition into an Lo environment are sequestered or concentrated in these rafts. A generalization of this hypothesis indicates that proteins dynamically partition into and out of rafts such that only a fraction of proteins are clustered in the rafts. Implicit in this hypothesis is the concept that rafts diffuse as stable entities that impose lateral heterogeneity on plasma-membrane proteins by virtue of the ability of the proteins to partition into the domains or not. These concepts flow directly from the biophysical studies that have already been outlined.

However, the surface distribution of green fluorescent protein (GFP)-labelled GPI (GFP–GPI) on the outer plasma membrane, as determined by a combination of homo-FRET imaging and mathematical modelling21,22, cannot be reconciled with this classic raft hypothesis22,23. Twenty to forty percent of GFP–GPI proteins are present as small clusters on length scales of 5–10 nm that comprise 3–4 proteins on average, with the remainder of the proteins distributed as monomers — however, this clustering is sensitive to cholesterol depletion22. Most interestingly, the ratio of monomers to clusters is not altered with increasing expression of GFP–GPI proteins22. A similar distribution, determined by a combination of EM spatial-point-pattern analysis and mathematical modelling, is seen for GFP-tH (which is GFP that is targeted to the plasma membrane by the dual palmitoylation and farnesylation anchoring of H-Ras). Forty percent of GFP-tH is present in clusters with a radius of 12–20 nm that comprise 6–7 proteins on average, with the remainder distributed randomly as monomers24. Clustering of GFP-tH is abrogated by cholesterol depletion or disassembly of the actin cytoskeleton and, as with GFP–GPI, the ratio of GFP-tH clusters to monomers does not change as a function of GFP-tH expression24,25. Computational modelling shows that a lack of dependence of the extent of clustering on expression level essentially excludes partitioning of GFP-tH into a fixed number of stable pre-existing raft domains24.

Single-particle tracking experiments at high temporal and moderate spatial resolution also indicate that single GPI-anchored proteins are associated with very small (<10 nm) domains with short lifetimes (<0.1 ms), although the size and stability of these domains increase if GPI-anchored proteins are crosslinked26. Moreover, the results of earlier FRET and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR)-spin labelling experiments can only be rationalized if rafts are small and unstable, or raft proteins exchange rapidly with non-raft membrane on a timescale of <0.1 ms (REFS 27,28). Other FRET studies have shown cholesterol-dependent clustering of certain lipid-anchored proteins on the inner leaflet, but did not estimate domain lifetime or an upper limit of domain size29.

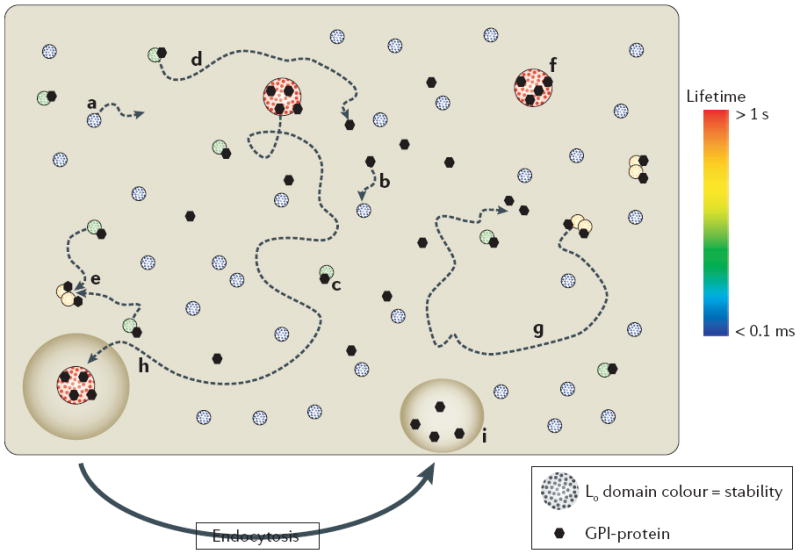

Starting from these data, consider the proposal that small, laterally mobile Lo domains form spontaneously in the plasma membrane as in model membranes (FIG. 2). The domains exist on short lengths and timescales (<10 nm and <0.1 ms, respectively) and are transient or unstable for several reasons, including physiological temperature and nanoscale heterogeneity in cholesterol distribution (BOX 3). These unstable rafts can however be captured and stabilized by lipid-anchored or transmembrane proteins. If the initial site for protein interaction is the boundary between the Lo domain and the adjacent Ld membrane, then proteins could function as surfactants, reducing line tension and therefore generating increased stability. In fact, preferential localization of lipid-anchored N-Ras to Lo–Ld domain boundaries has recently been shown in vitro using AFM30. Collision with other protein or lipid domains leads to the fusion of small domains into larger lipid-based protein assemblies and, therefore, the formation of protein clusters (FIG. 2). These basic properties of the model predict that cluster formation is cholesterol-dependent, but do not predict or require the existence of stable, pre-existing, large Lo domains. Larger, even more stable domains can be formed, but these require protein–protein interactions and/or crosslinking — as with the creation of T-cell-signalling domains31. Note that this model is different from the previously advanced lipid-shell hypothesis32, which suggests that lipid shells that are formed around lipid anchors operate as targeting motifs that allow interaction of the shelled protein with pre-existing lipid rafts or caveolae32.

Figure 2. Revised raft model.

Liquid ordered (Lo) domains in the plasma membrane are heterogeneous in size and lifetime (from >1 s to <0.1 ms, as indicated by colour). Lo domain stability or lifetime is a function of size, capture by a raft-stabilizing protein and protein–protein interactions of constituent proteins. The length of trajectories (dotted arrowed lines) and, therefore, the probability of collision with proteins or other Lo domains are proportional to lifetime. For simplicity, only sample trajectories are shown — however, all of the domains and proteins that are shown should be envisaged to diffuse laterally. The diagram illustrates the fate of different classes of Lo domain. Small, unstable Lo domains form spontaneously, diffuse laterally in the plasma membrane, but have a limited lifetime (a). If captured by a glycosylphosphatidylinisotol (GPI)-anchored protein (or other raft-stabilizing proteins) (b) the stability of the Lo domain is increased with the formation of a complex (c), which has two possible outcomes: the complex diffuses laterally but the Lo domain disassembles (d), or there is a collision with other protein-stabilized Lo domains that creates protein clusters (e). Further collisions will generate larger, more stable Lo–protein complexes (f) that are further stabilized by protein–protein interactions, or in the absence of collisions (g) the Lo–protein complex disassembles. The fate of larger, more stable Lo–protein complexes (h) is capture by endocytic pathways that disassemble the complexes and return lipid and protein constituents back to the plasma membrane (i). Intuitively, the model predicts the generation of protein clusters that is dependent on their interaction with Lo domains. Endocytosis indicates endocytosis that is specific for larger raft complexes (as shown), possibly all endocytic processes contribute to limiting the size of raft domains. Note that the larger, more stable lipid–protein complexes (f) could operate the way rafts are proposed to in the classic model, with dynamic partitioning of proteins between the domain and the surrounding disordered membrane (not shown).

Can the small, transient structures of the revised model be called rafts? This is almost a semantic question, but the answer is yes because there is a cholesterol-dependent lipid assembly present, even though longer-term stability requires the presence of protein. In the context of this model, two general classes of laterally diffusing plasma membrane proteins can be defined: those that are able to capture and stabilize small Lo domains (raft proteins), and those that cannot (raft excluded). It is possible that these classes represent two ends of a continuous spectrum in which proteins can show intermediate probabilities of capturing and stabilizing small Lo domains; in which case the likelihood of cluster formation and of finding a given protein in a raft cluster will correlate with the protein’s ability to stabilize an Lo domain.

Determinants of raft stability

The mobility and localization of a protein that is tethered by a lipid anchor is determined to some extent by the composition of the bilayer, as different lipid anchors preferentially associate with specific lipid assemblies; this is a mainstay of the raft hypothesis for lipid-based protein sorting. However, it is important to appreciate that the lipid anchor also has the capacity to modify its immediate lipid environment — for example, to facilitate or inhibit the chain and translational ordering of adjacent phospholipids. These phenomena have been clearly shown for lipidated peptides that interact with model membranes33-37. So, saturated lipid anchors might not only preferentially segregate to Lo domains, but also increase their stability by virtue of interactions with membrane-anchor phospholipids. Integral membrane proteins also organize lipids, as the intramembrane protein needs to be solvated by the flexible disordered chains of phospholipids. Indeed, Mouritsen’s hydrophobic matching hypothesis proposes that integral membrane proteins perturb surrounding lipids so that bilayer thickness matches the length of the transmembrane domain38. Consistent with this hypothesis, recent work indicates that proteins might be the most important determinant of membrane thickness, at least in the exocytic pathway39.

It remains an open question whether lipid-anchored and transmembrane proteins show differential abilities to function as surfactants at Lo–Ld boundaries, given their different mechanisms of organizing membrane lipids. Either way, as diameter increases, the stability of an Lo domain increases because of decreasing line tension with the surrounding Ld membrane. Extra stability will also be provided by protein–protein interactions between co-resident proteins that have an interaction with the Lo platform. In a general sense, this concept of proteins stabilizing a raft domain is simply another example of proteins organizing lipids, as with caveolin, sterol-sensing domain proteins, BAR (Bin, amphiphysin, Rvs)-domain proteins and myristoylated alanine-rich protein kinase C (PKC) substrate (MARCKS) protein. Reciprocally, lipids organize proteins, as with pleckstrin homology and FYVE domain proteins, annexins, PKC and C-Raf. Continuing the analogy with lipid-raft–protein interactions, many of these other protein–lipid interactions are very dynamic, with fast on and off rates and short lifetimes40. It is also worth considering whether the plasma-membrane picket fence (BOX 3) is actually required for the formation of transient Lo domains, as disassembling the actin cytoskeleton with latrunculin declusters GFP-tH as effectively as cholesterol depletion24.

A crucial feature of the revised model is the proposal that proteins have an active role in raft organization; two recent studies are directly relevant to this prediction. In an elegant set of SFVT experiments examining formation of T-cell receptor (TCR) signalling platforms, Douglass and Vale (REF. 31) showed that full-length lymphocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase (LCK) stably interacts with CD2-positive and linker for activation of T cells (LAT)-positive TCR-signalling domains, but that the minimal lipid anchor of LCK coupled to GFP does not. Similarly, Larson et al.41 showed that full length Lyn co-localizes (actually co-diffuses as this is an FCS analysis) with crosslinked immunoglobulin E (IgE) receptor, but again the minimal lipid anchor of Lyn coupled to GFP does not. In parallel, Gaus et al.42 have shown, using Laurdan imaging, that the lipids in and around the TCR–protein complex are ordered, which shows with some certainty that these signalling platforms are indeed large, stable Lo domains. Together, these observations raise an important question: why do a subset of lipid-modified GFP probes that putatively associate with Lo domains (raft markers) not associate with the large putative Lo domains that constitute the TCR and IgE receptor signalling platforms? The conclusion of Larson et al.41 is that a protein-interaction domain, provided by the activated kinase domain of Lyn, is required for stable association with the crosslinked-IgE receptor. A similar conclusion is equally plausible in the case of interactions between activated LCK with the TCR-signalling domain31. Analysis of the microlocalization of the minimal anchors of Lyn and LCK and the cognate full-length proteins has largely relied on detergent insolubility with all its inherent problems (BOX 2), except for a FRET study that showed cholesterol-dependent clustering of the minimal Lyn anchor29. The new studies31,41 show that the surface distribution of the minimal anchor and the full-length proteins are different, and therefore illustrate the importance of protein–protein as well as anchor–lipid-bilayer interactions in controlling the stable association of proteins with Lo domains.

There is an interesting analogy here with Ras. The minimal anchor of H-Ras attached to GFP (GFP-tH) localizes to Lo domains, whereas full-length activated H-Ras does not. Full-length Ras has a protein domain, adjacent to the anchor, that is required for the formation of non-raft microdomains that constitute the actual Ras signalling platform. Therefore, it is a combination of lipid anchor and protein-based sorting mechanisms that determines the final composition of an H-Ras-signalling complex24,43,44.

Limiting Lo domain size

The small, transient Lo domains might be expected to progressively coalesce into ever larger, and eventually macroscopic, domains once they are captured by proteins. This clearly does not occur because such domains are not detected in native cell membranes. Furthermore, at shorter-length scales significant aggregation does not occur, as evidenced by the clustering of GFP–GPI and GFP-tH in small nanodomains with a fixed monomer to cluster ratio at all expression levels22,24. The simplest explanation to account for these results is that there is an active, energy-dependent process that limits raft-domain size. A recent computational analysis of this problem considered small, spontaneously forming Lo domains that diffuse laterally and fuse on collision, and showed that endocytosis might be the process that limits raft-domain size45. This study showed that small domains in the modelled membrane would eventually fuse to one large raft, driven by the reduction of line tension discussed above. By contrast, active, selective removal of large rafts by endocytosis and recycling of disassembled, smaller raft units back to the model membrane limited raft size to a nanometer length scale45. In this context, it is worth noting that there are well-defined endocytic pathways that selectively internalize lipid-raft-associated proteins, and traffic through these pathways is increased after crosslinking the rafts into larger domains22,46. Intriguingly, a similar limitation in raft size was achieved by randomly recycling areas of membrane without any selection for large rafts45. This indicates that all endocytic processes might contribute to the active maintenance of small rafts on the plasma membrane.

Are small, short lifetime rafts useful?

It is also important to consider what small, unstable raft domains might be able to do. Is there actually an advantage to having multiple small domains? This is a difficult question to tackle experimentally, but it is amenable to computational approaches. For example, recent work with Ras signalling platforms indicates that compartmentalizing switch-like activation of the Raf–MEK (mitogen- activated protein kinase (MAPK) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase)–MAPK cascade across multiple nanoscale plasma-membrane domains allows high-fidelity transmembrane signal transmission from growth-factor receptors to MAPK activation (T. Tian, A. Harding and J.F.H.; personal communication). Furthermore, disrupting Ras nanoclustering using multiple different conditions significantly impairs Ras signalling24,44,47,48, which emphasizes the importance of nanocluster formation. It is tempting to speculate that lipid rafts might have similar roles in other signalling cascades. If this is the case, much larger and more stable rafts, or crosslinked rafts, might predominantly be required for protein trafficking and endocytosis, and for highly specialized functions such as those observed in caveolae or the T-cell synapse.

However, what if we consider that a crucial role of raft domains is to promote reactions between raft-partitioning proteins? Could the type of nanoscale domains proposed here realize this function? A recent computational modelling study of raft–protein dynamics provides some preliminary answers to these questions49. This study considered a classic raft model in which proteins dynamically partition into rafts. Inter-protein collisions were observed to be maximal when rafts were small (6–14 nm), mobile and when the diffusion rate of proteins in rafts was two-fold slower than the diffusion rate of proteins outside of rafts. Although the effect of raft instability per se was not investigated, the average residence time of a protein in a raft was <0.1 ms. So, although the simulations of protein dynamics were based on a model of stable raft domains, the conclusion is that transient, short-lifetime protein interactions with small lipid-raft domains might still facilitate useful biochemical reactions49.

Conclusions

An analysis of recent work with model membranes and intact plasma membranes, using experimental techniques that explore short length and timescales, together with computational modelling, indicate that a revised hypothesis for the structure and function of lipid-raft domains in the plasma membrane is warranted. This revised model needs to take into account a more dominant role for plasma-membrane proteins in capturing and stabilizing intrinsically unstable Lo domains. Importantly, this revised hypothesis indicates a series of testable predictions and offers what might be elusive common ground between two polarized standpoints: the idea that stable pre-existing rafts are the dominant organizing principle in the plasma membrane, versus the idea that rafts do not exist and therefore have no role in plasma membrane function. In summary, rafts exist, but their length and timescale specifications are crucially important characteristics that must be included in any definition.

To rigorously test the hypothesis, a wider application of imaging techniques that can explore short distances and timescales in intact membranes is needed to build a more extensive spatio–temporal map of proteins on the plasma membrane. Such studies will give deeper insights into the diverse mechanisms that drive plasma-membrane compartmentalization and show the overall significance of lipid–protein interactions in generating distinct membrane microdomains. Integrating different data sets will also require more in silico modelling of protein dynamics on the plasma membrane. Finally, the extent to which the inner and outer leaflets of the plasma membrane are coupled remains unknown. Progress in solving this complex problem will no doubt reveal new insights into plasma-membrane micro-organization and lipid-raft function.

Acknowledgments

I thank A. Yap, R. Parton and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript, and the National Health and Medical Research Council, Australia, and the National Institutes of Health, USA, for their continuing support. The Institute for Molecular Bioscience is a Special Research Centre of the Australian Research Council.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement The author declares no competing financial interests.

DATABASES

The following terms in this article are linked online to: UniProtKB: http://ca.expasy.org/sprot

CD2 ∣ H-Ras ∣ LAT ∣ LCK ∣ Lyn ∣ MARCKS ∣ N-Ras ∣ PLAP ∣ THY1

FURTHER INFORMATION

John Hancock’s homepage: http://www.imb.uq.edu.au/index.html?id=11726

Access to this Links box is available online.

References

- 1.Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edidin M. The state of lipid rafts: from model membranes to cells. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:257–283. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.142439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons K, Vaz WL. Model systems, lipid rafts, and cell membranes. Anna Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:269–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munro S. Lipid rafts: elusive or illusive? Cell. 2003;115:377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00882-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nichols B. Cell biology: without a raft. Nature. 2005;436:638–639. doi: 10.1038/436638a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Almeida RE, Fedorov A, Prieto M. Sphingomyelin–phosphatidylcholine–cholesterol phase diagram: boundaries and composition of lipid rafts. Biophys J. 2003;85:2406–2416. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(03)74664-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Almeida RF, Loura LM, Fedorov A, Prieto M. Lipid rafts have different sizes depending on membrane composition: a time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer study. J Mol Biol. 2005;346:1109–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown DA, Rose JK. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 1992;68:533–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90189-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown DA, London E. Structure of detergent-resistant membrane domains: does phase separation occur in biological membranes? Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:1–7. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.London E, Brown DA. Insolubility of lipids in triton X-100: physical origin and relationship to sphingolipid–cholesterol membrane domains (rafts) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1508:182–195. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4157(00)00007-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heberle FA, Buboltz JT, Stringer D, Feigenson GW. Fluorescence methods to detect phase boundaries in lipid bilayer mixtures. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silvius JR. Fluorescence energy transfer reveals microdomain formation at physiological temperatures in lipid mixtures modeling the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. Biophys J. 2003;85:1034–1045. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74542-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feigenson GW, Buboltz JT. Ternary phase diagram of dipalmitoyl-PC–dilauroyl-PC–cholesterol: nanoscopic domain formation driven by cholesterol. Biophys J. 2001;80:2775–2788. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76245-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuan C, Furlong J, Burgos P, Johnston LJ. The size of lipid rafts: an atomic force microscopy study of ganglioside GM1 domains in sphingomyelin–DOPC–cholesterol membranes. Biophys J. 2002;82:2526–2535. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75596-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsueh YW, Gilbert K, Trandum C, Zuckermann M, Thewalt J. The effect of ergosterol on dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine bilayers: a deuterium NMR and calorimetric study. Biophys J. 2005;88:1799–1808. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veatch SL, Polozov IV, Gawrisch K, Keller SL. Liquid domains in vesicles investigated by NMR and fluorescence microscopy. Biophys J. 2004;86:2910–2922. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74342-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Veatch SL, Keller SL. Seeing spots: Complex phase behavior in simple membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:172–185. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dietrich C, et al. Lipid rafts reconstituted in model membranes. Biophys J. 2001;80:1417–1428. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76114-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dietrich C, Volovyk ZN, Levi M, Thompson NL, Jacobson K. Partitioning of Thy-1, GM1, and cross-linked phospholipid analogs into lipid rafts reconstituted in supported model membrane monolayers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10642–10647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191168698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kahya N, Brown DA, Schwille P. Raft partitioning and dynamic behavior of human placental alkaline phosphatase in giant unilamellar vesicles. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7479–7489. doi: 10.1021/bi047429d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rao M, Mayor S. Use of Forster’s resonance energy transfer microscopy to study lipid rafts. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma P, et al. Nanoscale organization of multiple GPI-anchored proteins in living cell membranes. Cell. 2004;116:577–589. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayor S, Rao M. Rafts: scale-dependent, active lipid organization at the cell surface. Traffic. 2004;5:231–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plowman S, Muncke C, Parton RG, Hancock JF. H-ras, K-ras and inner plasma membrane raft proteins operate in nanoclusters that exhibit differential dependence on the actin cytoskeleton. Proc NatlAcad Sci USA. 2005;102:15500–15505. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504114102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prior IA, Muncke C, Parton RG, Hancock JF. Direct visualization of Ras proteins in spatially distinct cell surface microdomains. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:165–170. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusumi A, Koyama-Honda I, Suzuki K. Molecular dynamics and interactions for creation of stimulation-induced stabilized rafts from small unstable steady-state rafts. Traffic. 2004;5:213–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.0178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenworthy AK, Petranova N, Edidin M. High-resolution FRET microscopy of cholera toxin B-subunit and GPI-anchored proteins in cell plasma membranes. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:1645–1655. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawasaki K, Yin JJ, Subczynski WK, Hyde JS, Kusumi A. Pulse EPR detection of lipid exchange between protein-rich raft and bulk domains in the membrane: methodology development and its application to studies of influenza viral membrane. Biophys J. 2001;80:738–748. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76053-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zacharias DA, Violin JD, Newton AC, Tsien RY. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science. 2002;296:913–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1068539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nicolini C, et al. Visualizing association of N-Ras in lipid microdomains: influence of domain structure and interfacial adsorption. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:192–201. doi: 10.1021/ja055779x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Douglass AD, Vale RD. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein–protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell. 2005;121:937–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson RG, Jacobson K. A role for lipid shells in targeting proteins to caveolae, rafts, and other lipid domains. Science. 2002;296:1821–1825. doi: 10.1126/science.1068886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huster D, et al. Membrane insertion of a lipidated ras peptide studied by FTIR, solid-state NMR, and neutron diffraction spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4070–4079. doi: 10.1021/ja0289245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gorfe AA, Pellarin R, Caflisch A. Membrane localization and flexibility of a lipidated ras peptide studied by molecular dynamics simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15277–15286. doi: 10.1021/ja046607n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janosch S, et al. Partitioning of dual-lipidated peptides into membrane microdomains: lipid sorting vs peptide aggregation. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:7496–7503. doi: 10.1021/ja049922i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowat AC, et al. Farnesylated peptides in model membranes: a biophysical investigation. Eur Biophys J. 2004;33:300–309. doi: 10.1007/s00249-003-0368-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowat AC, Keller D, Ipsen JH. Effects of farnesol on the physical properties of DMPC membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1713:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen MO, Mouritsen OG. Lipids do influence protein function — the hydrophobic matching hypothesis revisited. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:205–226. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mitra K, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Taguchi T, Warren G, Engelman DM. Modulation of the bilayer thickness of exocytic pathway membranes by membrane proteins rather than cholesterol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4083–4088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307332101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho W, Stahelin RV. Membrane–protein interactions in cell signaling and membrane trafficking. Anna Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2005;34:119–151. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.33.110502.133337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Larson DR, Gosse JA, Holowka DA, Baird BA, Webb WW. Temporally resolved interactions between antigen-stimulated IgE receptors and Lyn kinase on living cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:527–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gaus K, Chklovskaia E, Fazekas de St Groth B, Jessup W, Harder T. Condensation of the plasma membrane at the site of T lymphocyte activation. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:121–131. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Murakoshi H, et al. Single-molecule imaging analysis of Ras activation in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:7317–7322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401354101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hancock JF, Parton RG. Ras plasma membrane signalling platforms. Biochem J. 2005;389:1–11. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner MS, Sens P, Socci ND. Nonequilibrium raft-like domains under continuous recycling. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95:168301. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.168301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirkham M, et al. Ultrastructural identification of uncoated caveolin-independent early endocytic vehicles. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:465–476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rotblat B, et al. Three separable domains regulate GTP-dependent association of H-ras with the plasma membrane. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6799–6810. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6799-6810.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roy S, et al. Individual palmitoyl residues serve distinct roles in H-ras trafficking, microlocalization, and signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6722–6733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6722-6733.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nicolau DV, Jr, Burrage K, Parton RG, Hancock JF. Identifying optimal lipid raft characteristics required to promote nanoscale protein–protein interactions on the plasma membrane. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;26:313–323. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.1.313-323.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McConnell HM, Radhakrishnan A. Condensed complexes of cholesterol and phospholipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1610:159–173. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00015-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McConnell HM, Vrljic M. Liquid-liquid immiscibility in membranes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2003;32:469–492. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Huang J, Feigenson GW. A microscopic interaction model of maximum solubility of cholesterol in lipid bilayers. Biophys J. 1999;76:2142–2157. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77369-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pandit SA, Jakobsson E, Scott HL. Simulation of the early stages of nano-domain formation in mixed bilayers of sphingomyelin, cholesterol, and dioleylphos phatidylcholine. Biophys J. 2004;87:3312–3322. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.046078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pandit SA, et al. Sphingomyelin–cholesterol domains in phospholipid membranes: atomistic simulation. Biophys J. 2004;87:1092–1100. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.041939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foster LJ, De Hoog CL, Mann M. Unbiased quantitative proteomics of lipid rafts reveals high specificity for signaling factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5813–5818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631608100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lichtenberg D, Goni FM, Heerklotz H. Detergent-resistant membranes should not be identified with membrane rafts. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Heerklotz H. Triton promotes domain formation in lipid raft mixtures. Biophys J. 2002;83:2693–2701. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75278-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heerklotz H, Szadkowska H, Anderson T, Seelig J. The sensitivity of lipid domains to small perturbations demonstrated by the effect of Triton. J Mol Biol. 2003;329:793–799. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00504-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kwik J, et al. Membrane cholesterol, lateral mobility, and the phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-dependent organization of cell actin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13964–13969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336102100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Subtil A, et al. Acute cholesterol depletion inhibits clathrin-coated pit budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6775–6780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pichler H, Riezman H. Where sterols are required for endocytosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1666:51–61. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hao M, Mukherjee S, Sun Y, Maxfield ER. Effects of cholesterol depletion and increased lipid unsaturation on the properties of endocytic membranes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:14171–14178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309793200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goodwin JS, Drake KR, Remmert CL, Kenworthy AK. Ras diffusion is sensitive to plasma membrane viscosity. Biophys J. 2005;89:1398–1410. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.055640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Niv H, Gutman O, Kloog Y, Henis YI. Activated K-Ras and H-Ras display different interactions with saturable nonraft sites at the surface of live cells. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:865–872. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pike LJ, Han X, Chung KN, Gross RW. Lipid rafts are enriched in arachidonic acid and plasmenylethanolamine and their composition is independent of caveolin-1 expression: a quantitative electrospray ionization/mass spectrometric analysis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2075–2088. doi: 10.1021/bi0156557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hao M, Maxfield FR. Characterization of rapid membrane internalization and recycling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15279–15286. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fujiwara T, Ritchie K, Murakoshi H, Jacobson K, Kusumi A. Phospholipids undergo hop diffusion in compartmentalized cell membrane. J. Cell Biol. 2002;157:1071–1081. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murase K, et al. Ultrafine membrane compartments for molecular diffusion as revealed by single molecule techniques. Biophys J. 2004;86:4075–4093. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.103.035717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schutz GJ, Kada G, Pastushenko VP, Schindler H. Properties of lipid microdomains in a muscle cell membrane visualized by single molecule microscopy. EMBO J. 2000;19:892–901. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.5.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang W, et al. Structural analysis of sterol distributions in the plasma membrane of living cells. Biochemistry. 2005;44:2864–2884. doi: 10.1021/bi048172m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roux A, et al. Role of curvature and phase transition in lipid sorting and fission of membrane tubules. EMBO J. 2005;24:1537–1545. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]