Abstract

The co-occurrence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Nicotine Dependence is common. Individuals with ADHD are more likely to initiate smoking and become dependent on nicotine than their non-ADHD counterparts, and recent evidence suggests that they may have more difficulty quitting smoking. Little is known about how to best approach treating these co-morbidities to optimize clinical outcome. Clinicians treating individuals with either ADHD or Nicotine Dependence should be aware of their common co-occurrence and the need to address both in treatment. This review of ADHD and Nicotine Dependence provides an overview of relevant epidemiology, bidirectional interactions, and implications for pharmacological and adjunctive psychosocial treatment.

Keywords: ADHD, Nicotine, Smoking, Tobacco, Treatment

A. Overview

This article is intended to provide a framework for understanding the clinical implications of the common co-occurrence of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Nicotine Dependence. First, the epidemiology of both disorders is reviewed, with special attention to their co-occurrence. Etiological and therapeutic interactions are discussed. Finally, a practical guide for approaching smoking cessation treatment for smokers with ADHD is provided.

B. ADHD and Cigarette Smoking: Epidemiology, Interactions, and Treatment Implications

B1. Epidemiology

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a common psychiatric disorder, with onset in early childhood, involving significantly impairing core symptoms of inattention (IN) and hyperactivity/impulsivity (HI).[1] ADHD is associated with a variety of adverse academic, social, and health outcomes. While ADHD was previously recognized as a disorder primarily of childhood and adolescence, emerging evidence suggests persistence of impairing symptoms into adulthood for many individuals with ADHD. In the United States, epidemiological evidence indicates that 3–10% of school age children and 4.4% of adults have ADHD.[2,3]

While overall rates of cigarette smoking in the United States have declined, smoking remains the leading cause of preventable death, with one in every five deaths in the U.S. related to smoking.[4] The average age of first cigarette use is 16.9 years, while 19% of 16–17 year olds, 33% of 18–20 year olds, 39% of 21–25 year olds, and 36% of 26–29 year olds have smoked in the last month.[5]

B2. Interactions

ADHD has been closely linked to cigarette smoking in a number of epidemiological studies. Individuals with ADHD become regular smokers at an earlier age and are about twice as likely to develop nicotine dependence when compared with their non-ADHD counterparts.[6,7] However, some debate has continued over the nature and mechanism of the ADHD-smoking association. Novelty seeking, a trait common among individuals with ADHD,[8,9] is associated with smoking risk.[10] The quantity of present ADHD symptoms appears to be associated with the risk for early smoking initiation, increased smoking amount, and increasing dependence on nicotine.[11] Some studies have suggested that IN symptoms drive this association,[12] while others have suggested that HI symptoms are more predictive of cigarette smoking,[13,14] or that the relative contributions of IN and HI symptoms to risk for nicotine dependence may differ depending on developmental period (adolescence versus young adulthood).[15] Still others have maintained that the link between ADHD and smoking is largely driven by common co-morbidities, such as conduct disorder, which itself is a robust predictor of nicotine dependence and substance abuse in general.[16] In a sample (n=334) of college students, our research group found that both HI and IN symptoms were associated with cigarette smoking.[17] Another recent study revealed that some genetic polymorphisms may interact with ADHD symptoms to increase risk for smoking.[18]

In addition to possessing an increased risk for cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence, individuals with ADHD may also have more difficulty quitting cigarettes.[19,20] Given that nicotine administration has been shown to acutely reduce ADHD symptoms even among nonsmokers,[21,22] it has been suggested that smokers with ADHD may be “self-medicating” with nicotine to reduce ADHD symptoms.[23,24] When attempting to quit smoking, individuals with ADHD may have more severe withdrawal symptoms, including irritability and difficulty concentrating.[25] A recent controlled laboratory study demonstrated that nicotine abstinence among smokers with ADHD is associated with greater worsening of attention and response inhibition.[26] In an analysis of over 400 adult participants in smoking cessation treatment studies, childhood ADHD diagnosis was significantly associated with treatment failure.[19]

Neurobiological processes may underlie the link between cigarette smoking and ADHD. Smoking leads to nicotine receptor activation, which in turn stimulates the release of several neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine, glutamate, serotonin, beta-endorphin, and GABA, all of which then mediate various effects of nicotine use (i.e., pleasure, arousal, cognitive enhancement, appetite suppression, reduction in anxiety/tension).[27,28] The core symptoms of ADHD have been posited to reflect an underlying deficit in behavioral inhibition,[29] a process that may be modulated by cholinergic and catecholaminergic systems.[30] Nicotine’s robust effect on these systems, with resultant enhancement in behavioral inhibition, may in part explain smoking as “self-medication” among individuals with ADHD.[28] Individuals with ADHD may additionally seek out nicotine for cognitive enhancing effects.[31]

B3. Treatment Implications

B3a. ADHD Pharmacotherapy

As ADHD symptoms predict cigarette smoking and nicotine dependence, it is important to explore the effects of ADHD treatment on smoking. The mainstay of ADHD treatment is pharmacotherapy with psycho-stimulants, which does not appear to increase or decrease subsequent risk of substance use disorders, including nicotine dependence.[32-36] In one of the few clinical studies to monitor smoking rates and medication status among adolescent smokers with ADHD, cigarette smoking was monitored via self-report, electronic diaries, and salivary cotinine levels.[37] Those who were receiving pharmacotherapy for ADHD smoked significantly less than those who did not receive medication treatment. Additionally, a recent longitudinal study of adolescents with ADHD suggested that treatment with stimulants (versus no treatment) reduces the risk for later smoking.[38] Of potential concern, though, laboratory studies among smokers without ADHD have shown that stimulant administration may acutely increase cigarette smoking,[39-41] potentially owing to a synergistic effect of stimulants and nicotine on mesocorticolimbic dopamine levels.[42-43] This concern may be tempered by evidence that bupropion, which has been consistently shown to be effective for smoking cessation, also acutely increases smoking rate in a laboratory setting.[39]

Atomoxetine and bupropion, among other medications used in the treatment of ADHD, may hold appeal in the treatment of patients with co-morbid nicotine dependence. Bupropion is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States as a smoking cessation treatment. Atomoxetine, in contrast to stimulants and bupropion, does not acutely increase smoking rate.[41] It may also reduce subjective withdrawal symptoms and craving during acute nicotine abstinence.[44]

B3b. Nicotine Dependence Pharmacotherapy

Nicotine replacement, well established as a smoking cessation aid, has not specifically been investigated in individuals with ADHD. However, evidence that ADHD symptoms improve with nicotine administration among nonsmokers suggests that there may be theoretical potential for a combined therapeutic effect for nicotine dependence and ADHD.[21,22]

Bupropion is another effective smoking cessation treatment.[45,46] It has additionally shown efficacy in treating ADHD,[47] but has only been specifically investigated for smoking cessation in individuals with ADHD in one pilot study.[48] Further research is needed to determine whether bupropion can effectively treat both conditions simultaneously.

Varenicline has demonstrated efficacy superior to placebo, nicotine replacement, and bupropion in smoking cessation,[49-51] but no published studies have specifically investigated individuals with ADHD. Of note, a recent case report suggests that the smoking cessation effects of varenicline may be interrupted by administration of the psycho-stimulant amphetamine-dextroamphetamine.[52]

B3c. Psychosocial Treatment for Nicotine Dependence

A critical component in smoking cessation treatment is psychosocial intervention. Clinicians, particularly those treating ADHD, should advise patients and families of the potential risks of tobacco use and monitor for use at every visit.[53] The cornerstone for provision of smoking cessation treatment should be the 5-A Method (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange).[54] Among smoking cessation interventions targeting young people, those that incorporate motivational enhancement, cognitive-behavioral, and contingency management approaches may be most associated with success.[55-57]

Motivational enhancement therapy is designed to elicit and support readiness to quit smoking.[58,59] Using this method, the clinician and patient discuss the patient’s smoking patterns, beliefs and thoughts about smoking, and level of motivation or desire to cease smoking. Ambivalence is addressed, and goals for behavioral change (i.e., increasing readiness to quit, initiating a smoking reduction attempt, or initiating a quit attempt) are developed collaboratively.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy seeks to identify and combat maladaptive cognitive and behavioral patterns that support cigarette smoking.[60] The patient works with the clinician to develop techniques for self-monitoring and improved coping and problem-solving skills, with the goal of the patient developing self-efficacy with carrying out these techniques even after the course of therapy has concluded.

Built upon the theoretical foundation of operant conditioning, contingency management interventions provide contingent rewards for cigarette reduction and abstinence.[55] Contingent rewards may include monetary payment, redeemable vouchers, or opportunities to draw prizes from a bowl containing rewards of varying values.

Combined approaches, involving multiple psychosocial modalities, may show added promise.[61,62] The principles underlying motivational enhancement therapy, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and contingency management may indeed be more complementary than overlapping when applied to smoking cessation treatment.

C. Practical Guide to Smoking Cessation in Patients with ADHD and Nicotine Dependence

Given the overall dearth of studies specifically investigating smoking cessation treatment in individuals with ADHD, the clinician is faced with the task of compiling disparate areas of research into a practical approach to patient care. Ideally, a single treatment would fully address both nicotine dependence and ADHD, but evidence does not currently support any single intervention for both disorders. In light of that limitation, the goal of treatment of these co-morbid conditions is to provide the best evidence-based approach to each condition while incorporating understanding of the relationship between the two.

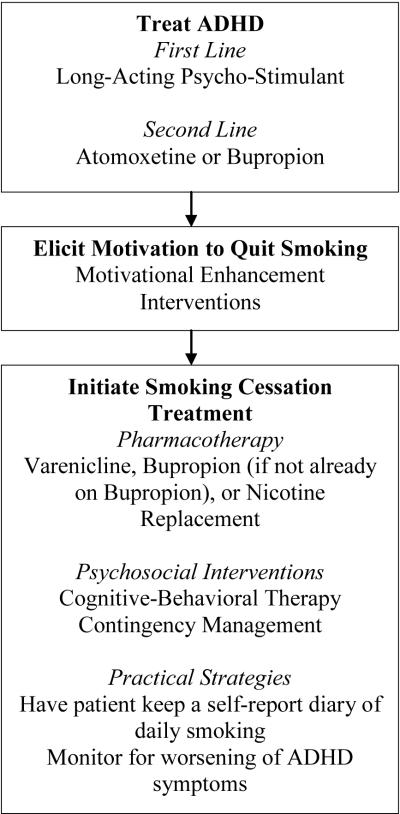

In general, we recommend stabilization of ADHD symptoms as the first priority of treatment since smoking cessation over the background of untreated ADHD could lead to greater relapse to smoking. Based on current evidence, this initial step should include pharmacotherapy. The second step is to encourage the patient’s motivation to quit smoking cigarettes. Once that is established, the third step is to initiate smoking cessation treatment, either with or without pharmacotherapy, depending on individual patient considerations. The fourth step is to work closely with the patient during the smoking cessation process, closely monitoring and addressing symptoms of ADHD and nicotine withdrawal. Details of treatment choices for these interventions are discussed below. Please see Figure 1 for an overview of our recommended approach.

Figure 1.

Step-wise approach to treating co-morbid ADHD and nicotine dependence

In regard to ADHD, pharmacotherapy is a key component of treatment. Additionally, since evidence indicates that active symptoms of ADHD convey increased risk for cigarette smoking[63] and difficulty quitting, medication treatment that successfully reduces symptoms may indirectly impact smoking cessation outcome. Since psycho-stimulants convey the most robust effect size, and since long-acting (compared with immediate-acting) stimulants possess reduced potential for misuse or diversion,[64] the first line medication treatment for ADHD is a long-acting psycho-stimulant. However, since some research has suggested that stimulants may acutely increase cigarette smoking, it is important to monitor smoking rates in ADHD patients initiating stimulant treatment. If a patient has difficulty tolerating a stimulant due to adverse effects, evidence-based alternatives include atomoxetine and bupropion. While effect sizes for these agents are not as large as those for stimulants, they are significant when compared with placebo. An additional benefit of bupropion is that it is also an effective treatment for smoking cessation. Of note, though, no published studies have demonstrated that bupropion is effective for ADHD symptoms in cigarette smokers or for smoking cessation among individuals with ADHD.

In regard to smoking cessation, varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine replacement are all first-line medication treatments. Head-to-head studies comparing varenicline with bupropion indicate that varenicline may be more effective. Although bupropion and nicotine replacement, as discussed previously, may possess theoretical advantages in treating smokers with ADHD, in light of the paucity of clear evidence, we recommend using the medication with the greatest probability for successful smoking cessation (varenicline). There may be other considerations (e.g., adverse effects) that may lead to the use of other medications over varenicline.

We recommend that ADHD symptoms be monitored during treatment with a rating scale, such as the ADHD Rating Scale IV.[65] Cigarette smoking may be monitored using a self-report instrument, such as the Timeline Follow-Back method.[66] If available, biological confirmation of abstinence may be achieved using a carbon monoxide breathalyzer and/or urine cotinine measurement.

Regardless of the pharmacotherapy (if any) chosen for smoking cessation, it is important to incorporate psychosocial interventions into treatment. We recommend a combined approach, based on the evidence, which incorporates motivational enhancement, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and/or contingency management. Initially, the patient’s motivation to quit smoking cigarettes must be established. Building upon that, the patient’s cognitive and behavioral patterns that reinforce smoking may be identified and challenged. Additionally, if possible, plans for contingent rewards for smoking abstinence may be established. The rewards should be developmentally and individually motivating, and do not have to be of great monetary value. Contingent reinforcement helps to maintain the motivation that was initially elicited using motivational enhancement interventions. The structure conveyed by a series of short-term contingent rewards may be especially helpful for patients with ADHD, who may struggle with organization and long-term planning. Recently published expert guidelines for the treatment of nicotine dependence may help guide pharmacological and psychosocial treatment.[53,67]

It is important to note that, even among smokers without co-morbid ADHD, relapse rates are very high. It is expected that many patients will have difficulty quitting and may relapse after quitting. In the especially challenging circumstance of treating the patient with co-morbid ADHD and nicotine dependence, the clinician must avoid becoming discouraged in light of patient relapse. The clinician should continue to treat ADHD and encourage the patient’s motivation to quit smoking. When the patient is ready for another quit attempt, the clinician should again provide a structured approach to cessation based on the current evidence.

With further research, it is hoped that integrated treatment specific to patients with ADHD and nicotine dependence will be developed. In the interim, when incorporating emerging data on both disorders, their interactions, and their treatments, the clinician can make informed treatment decisions that can make potentially significant impacts on morbidity and mortality.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. American Psychiatric Association; Washington DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, Biederman J. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World Psychiatry. 2003;2:104–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, Biederman J, Conners CK, Demler O, Faraone SV, Greenhill LL, Howes MJ, Secnik K, Spencer T, Ustun TB, Walters EE, Zaslavsky AM. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716–723. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.4.716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Targeting Tobacco Use: The Nation’s Leading Cause of Preventable Death 2007. 2007 Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/publications/aag/pdf/osh.pdf.

- 5.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Office of Applied Studies . Results from the 2007 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2008. NSDUH Series H-34, DHHS Publication No. SMA 08-4343. Available online at http://oas.samhsa.gov/NSDUH/2k7NSDUH/2k7results.cfm#Ch4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lambert NM, Hartsough CS. Prospective study of tobacco smoking and substance dependencies among samples of ADHD and non-ADHD participants. J Learn Disabil. 1998;31:533–544. doi: 10.1177/002221949803100603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Milberger S, Biederman J, Faraone SV, Chen L, Jones J. ADHD is associated with early initiation of cigarette smoking in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:37–44. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199701000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anckarsäter H, Stahlberg O, Larson T, Hakansson C, Jutblad SB, Niklasson L, Nydén A, Wentz E, Westergren S, Cloninger CR, Gillberg C, Rastam M. The impact of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders on temperament, character, and personality development. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1239–1244. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.7.1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho SC, Hwang JW, Lyoo IK, Yoo HJ, Kin BN, Kim JW. Patterns of temperament and character in a clinical sample of Korean children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62:160–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2008.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tercyak KP, Audrain-McGovern J. Personality differences associated with smoking experimentation among adolescents with and without comorbid symptoms of ADHD. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:1953–1970. doi: 10.1081/ja-120025121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kollins SH, McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF. Association between smoking and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in a population-based sample of young adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1142–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.10.1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tercyak KP, Lerman C, Audrain J. Association of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms with levels of cigarette smoking in a community sample of adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:799–805. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200207000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elkins IJ, McGue M, Iacono WG. Prospective effects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, and sex on adolescent substance use and abuse. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1145–1152. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuemmeler BF, Kollins SH, McClernon FJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms predict nicotine dependence and progression to regular smoking from adolescence to young adulthood. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32:1203–1213. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodriguez D, Tercyak KP, Audrain-McGovern J. Effects of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms on development of nicotine dependence from mid adolescence to young adulthood. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:563–575. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brook JS, Duan T, Zhang C, Cohen PR, Brook DW. The association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescence and smoking in adulthood. Am J Addict. 2008;17:54–59. doi: 10.1080/10550490701756039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Upadhyaya HP, Carpenter MJ. Is attention deficit hyperactivity disorder symptom severity associated with tobacco use? Am J Addict. 2008;17:195–198. doi: 10.1080/10550490802021937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McClernon FJ, Fuemmeler BF, Kollins SH, Kail ME, Ashley-Koch AE. Interactions between genotype and retrospective ADHD symptoms predict lifetime smoking risk in a sample of young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:117–127. doi: 10.1080/14622200701704913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humfleet GL, Prochaska JJ, Mengis M, Cullen J, Muñoz R, Reus V, Hall SM. Preliminary evidence of the association between the history of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and smoking treatment failure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7:453–460. doi: 10.1080/14622200500125310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pomerleau CS, Downey KK, Stelson FW, Pomerleau CS. Cigarette smoking in adult patients diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Subst Abuse. 1995;7:373–378. doi: 10.1016/0899-3289(95)90030-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levin ED, Conners CK, Sparrow E, Hinton SC, Erhardt D, Meck WH, Rose JE, March J. Nicotine effects on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;123:55–63. doi: 10.1007/BF02246281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potter AS, Newhouse PA. Acute nicotine improves cognitive deficits in young adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2008;88:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gehricke JG, Whalen CK, Jamner LD, Wigal TL, Steinhoff K. The reinforcing effects of nicotine and stimulant medication in the everyday lives of adult smokers with ADHD: A preliminary examination. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:37–47. doi: 10.1080/14622200500431619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lerman C, Audrain J, Tercyak K, Hawk LW, Jr, Bush A, Crystal-Mansour S, Rose C, Niaura R, Epstein LH. Nicotine Tob Res. 2001;3:353–359. doi: 10.1080/14622200110072156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pomerleau CS, Downey KK, Snedecor SM, Mehringer AM, Marks JL, Pomerleau OF. Smoking patterns and abstinence effects in smokers with no ADHD, childhood ADHD, and adult ADHD symptomatology. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1149–1157. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(02)00223-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McClernon FJ, Kollins SH, Lutz AM, Fitzgerald DP, Murray DW, Redman C, Rose JE. Effects of smoking abstinence on adult smokers with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: results of a preliminary study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;197:95–105. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mansvelder HD, McGehee DS. Cellular and synaptic mechanisms of nicotine addiction. J Neurobiol. 2002;53:606–617. doi: 10.1002/neu.10148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newhouse P, Singh A, Potter A. Nicotine and nicotinic receptor involvement in neuropsychiatric disorders. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2004;4:267–282. doi: 10.2174/1568026043451401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin. 1997;121:65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brennan AR, Arnsten AF. Neuronal mechanisms underlying attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: the influence of arousal on prefrontal cortical function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:236–45. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalil KL, Bau CH, Grevet EH, Sousa NO, Garcia CR, Victor MM, Fischer AG, Salgado CA, Belmonte-de-Abreu P. Smoking is associated with lower performance in WAIS-R Block Design scores in adults with ADHD. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:683–688. doi: 10.1080/14622200801979019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Macpherson HA, Faraone SV. Stimulant therapy and risk for subsequent substance use disorders in male adults with ADHD: a naturalistic controlled 10-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:597–603. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07091486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faraone SV, Biederman J, Wilens TE, Adamson J. A naturalistic study of the effects of pharmacotherapy on substance use disorders among ADHD adults. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1743–1752. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huss M, Poustka F, Lehmkuhl G, Lehmkuhl U. No increase in long-term risk for nicotine use disorders after treatment with methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): evidence from a non-randomised retrospective study. J Neural Transm. 2008;115:335–339. doi: 10.1007/s00702-008-0872-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Truong NL, Moulton JL, 3rd, Roizen ER, Howell KH, Castellanos FX. Age of methylphenidate treatment initiation in children with ADHD and later substance abuse: prospective follow-up into adulthood. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:604–609. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07091465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Molina BS, Pelham WE, The MTA Cooperative Group Development of substance use among youth with ADHD; Panel session presentation, The American College of Neuropsychopharmacology annual meeting; Hollywood, Florida. December 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whalen CK, Jamner LD, Henker B, Gehricke JG, King PS. Is there a link between adolescent cigarette smoking and pharmacotherapy for ADHD? Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17:332–335. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.17.4.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilens TE, Adamson J, Monuteaux MC, Faraone SV, Schillinger M, Westerberg D, Biederman J. Effect of prior stimulant treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on subsequent risk for cigarette smoking and alcohol and drug use disorders in adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:916–921. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.10.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cousins MS, Stamat HM, de Wit H. Acute doses of d-amphetamine and bupropion increase cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2001;157:243–253. doi: 10.1007/s002130100802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rush CR, Higgins ST, Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PEA. Methylphenidate increases cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181:781–789. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Glaser PE, Rush CR. A pharmacological analysis of stimulant-induced increases in smoking. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;193:305–313. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0786-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gerasimov MR, Franceschi M, Volkow ND, Rice O, Schiffer WK, Dewey SL. Synergistic interactions between nicotine and cocaine or methylphenidate depend on the dose of dopamine transporter inhibitor. Synapse. 2000;38:432–437. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20001215)38:4<432::AID-SYN8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huston-Lyons D, Sarkar M, Kornetsky C. Nicotine and brain stimulation reward: interactions with morphine, amphetamine and pimozide. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1993;46:453–457. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(93)90378-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ray R, Rukstalis M, Jepson C, Strasser AA, Patterson F, Lynch K, Lerman C. Effects of atomoxetine on subjective and neurocognitive symptoms of nicotine abstinence. J Psychopharmacol. 2008 doi: 10.1177/0269881108089580. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hurt RD, Sachs DP, Glover ED, Offord KP, Johnston JA, Dale LC, Khayrallah MA, Schroeder DR, Glover PN, Sullivan CR, Croghan IT, Sullivan PM. A comparison of sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1195–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710233371703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jorenby DE, Leischow SJ, Nides MA, Rennard SI, Johnston JA, Hughes AR, Smith SS, Muramoto ML, Daughton DM, Doan K, Fiore MC, Baker TB. A controlled trial of sustained-release bupropion, a nicotine patch, or both for smoking cessation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:685–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903043400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilens TE, Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Girard K, Doyle R, Prince J, Polisner D, Solhkhah R, Comeau S, Monuteaux MC, Parekh A. A controlled clinical trial of bupropion for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:282–288. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Upadhyaya HP, Brady KT, Wang W. Bupropion SR in adolescents with comorbid ADHD and nicotine dependence: a pilot study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:199–205. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200402000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aubin H-J, Bobak A, Britton JR, Oncken C, Billing CB, Gong J, Williams KE. Varenicline versus transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation: results from a randomized open-label trial. Thorax. 2008 doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.090647. doi:10.1136/thx.2007.090647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzales D, Rennard SI, Nides M, Oncken C, Azoulay S, Billing CB, Watsky EJ, Gong J, Williams KE, Reeves KR, Varenicline Phase 3 Study Group Varenicline, an alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs sustained-release bupropion and placebo for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296:47–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nides M, Oncken C, Gonzales D, Rennard S, Watsky EJ, Anziano R, Reeves KR. Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7-week, randomized, placebo- and bupropion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 166:1561–1568. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.15.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Whitley HP, Moorman KL. Interference with smoking-cessation effects of varenicline after administration of immediate-release amphetamine-dextroamphetamine. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27:1440–1445. doi: 10.1592/phco.27.10.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement [Accessed July 14, 2008];Health care guideline: tobacco use prevention and cessation for adults and mature adolescents. 2007 http://www.icsi.org/tobacco_use_prevention_and_cessation_for_adults/tobacco_use_prevention_and_cessation_for_adults_and_mature_adolescents_2510.html.

- 54.Fiore M. Treating tobacco use and dependence. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; Rockville, Md.: [Accessed July 14, 2008]. 2000. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?rid=hstat2.chapter.7644. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Krishnan-Sarin S, Duhig AM, McKee SA, McMahon TJ, Liss T, McFetridge A, Cavallo DA. Contingency management for smoking cessation in adolescent smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacology. 2006;14:306–310. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.14.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roll JM. Assessing the feasibility of using contingency management to modify cigarette smoking by adolescents. J Appl Behav Anal. 2005;38:463–467. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.114-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sussman S, Sun P, Dent CW. A meta-analysis of teen cigarette smoking cessation. Health Psychol. 2006;25:549–557. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. Guilford Press; New York: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Miller WR, Zweben A, DiClemente CC, Rychtarik RG. Motivational enhancement therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol and drug dependence. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 1995. NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series, 2, DHHS Publication No. 94-3723. [Google Scholar]

- 60.McDonald P, Colwell B, Backinger CL, Husten C, Maule CO. Better practices for youth tobacco cessation: evidence of review panel. Am J Health Behav. 2003;27:S144–S158. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.27.1.s2.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cavallo DA, Cooney JL, Duhig AM, Smith AE, Liss TB, McFetridge AK, Babuscio T, Nich C, Carroll KM, Rounsaville BJ, Krishnan-Sarin S. Combining cognitive behavioral therapy with contingency management for smoking cessation in adolescent smokers: a preliminary comparison of two different CBT formats. Am J Addict. 2007;16:468–474. doi: 10.1080/10550490701641173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grimshaw GM, Stanton A. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub4. CD003289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Upadhyaya HP, Rose K, Wang W, O’Rourke K, Sullivan B, Deas D, Brady KT. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, medication treatment, and substance use patterns among adolescents and young adults. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:799–809. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, Sqambati S, Rotrosen J, Sawtelle R, Utzinger L, Fusillo S. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:21–31. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31815a56f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. ADHD Rating Scale - IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. Bethlehem, PA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sobell LC, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Cancilla A. Reliability of a timeline method: assessing normal drinkers’ reports of recent drinking and a comparative evaluation across several populations. Br J Addiction. 1988;83:393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1988.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fiore M, et al. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:158–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009. Available at: http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/tobacco/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]