Abstract

Aims

To determine whether there is a sequence in which adolescents experience symptoms of nicotine dependence (ND) as per the DSM-IV.

Design

A two-stage design was implemented to select a multi-ethnic target sample of adolescents from a school survey of 6th-10th graders from the Chicago Public Schools. The cohort was interviewed at home with structured computerized interviews 5 times at 6-month intervals over a two-year period.

Participants

Subsample of new tobacco users (N=353) who had started to use tobacco within 12 months prior to Wave 1 or between Waves 1-5.

Measurements and statistical methods

Monthly histories of DSM-IV symptoms of ND were obtained. Log-Linear quasi-independence models were estimated to identify the fit of different cumulative models of progression among the four most prevalent dependence criteria (tolerance, impaired control, withdrawal, unsuccessful attempts to quit), indexed by specific symptoms, by gender and race/ethnicity.

Findings

Pathways varied slightly across groups. The proportions who could be classified in a progression pathway not by chance ranged from 51% to 69%. Overall, tolerance and impaired control appeared first and preceded withdrawal; impaired control preceded attempts to quit. For males, tolerance was experienced first, with withdrawal a minor path of entry; for females withdrawal was experienced last, tolerance and impaired control were experienced first. For African Americans, tolerance by itself was experienced first; for other groups an alternative path began with impaired control.

Conclusions

The prevalence and sequence of criteria of ND fit our understanding of the neuropharmacology of ND. The order among symptoms early in the process of dependence may differ from the severity order of symptoms among those who persist in smoking.

Keywords: Nicotine dependence, criteria of dependence, symptoms of dependence, sequencing, development, adolescence

Introduction

Over the last several years, advances have been made in understanding the development of ND. Several research groups have documented that dependence, and not only tobacco use, begins in adolescence [1-7], and that ND can develop quickly following smoking initiation and at very low levels of consumption [1, 4]. Understanding the full developmental course of addiction requires understanding four underlying processes: (1) When in the lifecycle are symptoms of dependence first experienced? (2) How long after the onset of tobacco use does it take to become dependent? (3) What is the subsequent symptomatic course following the initial experience of dependence? (4) Are there specific sequences according to which symptoms are experienced? These questions have to be explored in adolescence when dependence has its onset.

Most investigations have focused on the first two questions: establishing the prevalence and latency to dependence in adolescence [2-4, 8]. Our group has also addressed the third question and examined developmental trajectories of ND symptoms over a two-year period [9]. We identified four groups: (1) experienced no symptoms; (2) developed symptoms very rapidly and remained chronically dependent throughout the period of observation; (3) developed symptoms very rapidly, then remitted; (4) developed symptoms slowly after a relatively long period of time. Thus, our prior work focused on the prevalence, latency, and developmental course of ND. We here address the fourth issue: Is there a discernable sequence in which young people experience the criteria that define the syndrome of ND?

This issue has not been addressed with epidemiological data, although neurobiological and theoretical discussions of addiction and dependence often assume an order between symptoms, in particular tolerance and withdrawal [10-13]. As stressed by Shadel et al. [13], understanding the development of ND requires understanding the order in which particular features of dependence unfold in adolescence: “Which features appear first? Is there a fixed sequence of appearance? Does this imply a causal chain, in which the emergence of one feature causes the next one to emerge?” (p.18) We here address the first two of these questions.

Detailed monthly assessments of symptoms of nicotine dependence as per the DSM-IV [14] made it possible to investigate potential sequences according to which criteria, comprising one or more symptomatic indicators, are experienced by adolescents. We examined sequences separately for males and females, and non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic African Americans, and Hispanics. With one exception, with no prior relevant work, we could not outline hypotheses regarding specific sequences and gender or ethnic differences. Based on the neurobiology of addiction, we expected that tolerance would precede withdrawal.

Methods

Sample

The analyses are based on five waves of interviews with a subsample from a multi-ethnic longitudinal cohort of 1,039 6th-10th graders from the Chicago Public Schools. A two-stage design was implemented to select efficiently the target sample for follow-up. In Phase I (spring 2003), 15,763 students in grades 6-10 sampled from 43 public schools were administered a brief self-administered questionnaire. Responses were used to select a target sample of 1,236 youths: 1,106 tobacco users who reported having started to use tobacco in the prior 12 months and 130 non-tobacco users susceptible of starting to smoke [15], divided as evenly as possible among non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic African-Americans and Hispanics. Whites and African Americans who started using tobacco 0-12 months earlier and Hispanics who started 0-6 months earlier were selected with certainty; Hispanics who started 7-12 months earlier were sampled at a 25% rate because of the larger number of Hispanics than other race/ethnic groups in the sample schools. In Phase II, on average 9 weeks after each school survey, 1,039 (84.1%) of targeted youths and one parent agreed to participate in the longitudinal follow-up consisting of three annual computer assisted personal household interviews with youths and parents, each about 90 minutes long (Waves 1, 3, 5), and two interim bi-annual interviews (20 minutes long) with youths (Waves 2, 4), collected from 2/03 - 10/05. The average interval between waves was 6.0-6.3 months, range=3-10. Completion rates at each wave were 96% of the Wave 1 sample. See also [4]. The field work was conducted by NORC, University of Chicago.

Human subject procedures

Passive parental consent was obtained for the school survey (parents returned a form only to refuse their child’s participation) and active consent for the household interviews. Adolescent assent was obtained for school and household interviews. The interviewers emphasized that all answers would be kept completely confidential. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Columbia University, and NORC.

Data collection

At each of the five waves, tobacco use patterns were ascertained for cigarettes, cigars, pipes, bidis, kreteks, and smokeless tobacco. The interview included a tobacco use history chart that obtained detailed monthly information on smoking patterns (number of days had smoked, average number of cigarettes smoked per day each month) for the 12 months preceding the Wave 1 interview and the intervals since each prior interview at Waves 2-5. A unique component of the chart was the monthly ascertainment of specific DSM-IV dependence symptoms between successive waves as of Wave 1. At Wave 1, the onset month of each DSM-IV symptom experienced the prior 12 months was assessed.

Measurement of ND

ND was measured as per the DSM-IV, with a scale developed for adolescents and young adults, with high internal reliability and concurrent, predictive and incremental validity [16, 17]. The 11-item scale measured symptoms that defined the seven DSM-IV dependence criteria experienced following the use of specific tobacco products (α = 0.84) [4, 18]. A criterion could be indexed by one or more items. The interviews personalized the questions to specify the products used by respondents [4]. Dependence was defined when subjects reported experiencing three criteria within a twelve-month period. The DSM-IV [14] uses the terms symptoms and criteria interchangeably and somewhat inconsistently.

Analytical sample

To minimize retrospective reports, the analytical sample included 353 new tobacco users, who had initiated use of tobacco within 12 months preceding Wave 1 (N=286) or between Waves 1 and 5 (N=67), had no missing data on DSM-IV symptoms, and could time the onset of their first symptom. Nineteen youths could not do so and were excluded. Smoking only one or two puffs qualified smokers for inclusion in the sample. Of those who started using tobacco within the 12 months prior to Wave 1, 16.0% started within the prior 3 months, 26.7% 4-6 months earlier, 29.0% 7-9 months earlier, and 28.3% 10-12 months earlier.

At Wave 1, adolescents were on average 14.0 years old (SD=1.3), range 11-17 years; 42.7% were male, 57.3% female. The racial/ethnic distribution was non-Hispanic white (29.1%), non-Hispanic African American (26.8%), Hispanic (44.1%). Most had smoked cigarettes (95.7%). Other products used were cigars (36.9%), smokeless tobacco (3.9%), kreteks (3.1%), pipes (3.2%), bidis (1.9%). The average onset age of tobacco use was 13.8 years (SD=1.3), range 10-17 years.

Analytical strategies: Modified Guttman scaling

The analytical strategies are based on log-linear models used in prior analyses of stages in drug use [19-23]. Since sequential analysis increases greatly in complexity with increases in the number of events [22], and given the sample size, the analysis was restricted to the four most prevalent criteria: tolerance, impaired control, withdrawal, unsuccessful attempts to quit (See below). Analyses of progression were based on the temporal order of events from the year and month of onset ascertained for each criterion. Major pathways of progression were identified from the ordering of initiation among the four criteria and specific cumulative progression models (or scale types) were tested for fit to the data. The proportion of persons classified in the hypothesized progression models not by chance beyond that expected from the prevalence of the criteria was estimated. For a given model of progression, the observed proportion of individuals who could be classified in the progression model was calculated, although, as in Guttman scaling, not all individuals were required to reach the highest stage in the progression.

Log linear quasi-independence models were applied to identify the efficiency of different cumulative progression models in fitting the data [21-23]. In testing the fit of a model, it is important to ascertain not only the observed proportion of individuals who fall in a progression model (scale type) but also the expected proportion not due to chance, controlling for the differential probabilities of experiencing each criterion. For a given specification of scale and non-scale types, and the assumption that the non-scale type can occur only by chance, the maximum likelihood estimates of five parameters is obtained. One parameter, λ, is a constant fixing the total frequency of persons whose pattern of progression, whether or not it ends in the scale type, occurs by chance (random-type); the other four parameters, λTi, λIj, λWk, and λQl, fix the marginal probabilities of initiation for each dependence criterion among persons in the random-type group. The expected proportion of persons in the scale type not by chance is given by [f-F (chance)]/f where f is the observed frequency and F (chance) is the frequency expected by chance [22]. The likelihood ratio chi-square statistic (χ2LR) associated with maximum likelihood estimation is used to assess the relative goodness of fit between nested models of sequences of progression. If the difference in χ2LR between two hierarchical models is smaller than the critical value at p<0.05 for the difference in degrees of freedom (DF) between the two models, the model with the higher DF provides a better fit. If the difference in chi-square is larger than the critical value, the model with the lower DF fits better. If the difference in the likelihood ratio is almost equal to the critical value, e.g., models 2C and 2D for females, both fit equally well.

Results

Prevalence of dependence criteria

These youths were light tobacco users. By Wave 5, 26.9% of smokers had ever smoked less than one cigarette, 8.9% a whole cigarette, 18.3% 2-5 cigarettes, 11.4% 6-15 cigarettes, 7.4% 16-25 cigarettes, 7.9% 26-99 cigarettes, 19.2% 100 or more cigarettes; 10.1% had ever used any tobacco product daily.

Over half (52.5%) reported at least one DSM-IV ND criterion by Wave 5, 39.7% two or more criteria, 26.2% three or more criteria. Among those who experienced at least one criterion, the majority experienced only one (24.4%) or two (25.7%) criteria. The remaining frequency distribution was three criteria 18.3%, four 8.3%, five 17.0%, six 3.2%, and seven criteria 3.1%. All those who experienced three or more criteria did so within a 12-month period and met criteria for full dependence. There were sharp differences in the prevalence of criteria. Tolerance, impaired control, and withdrawal were the most prevalent .By Wave 5, the prevalences were 36.9%, 36.9% and 29.7%, respectively, for these three, compared with 16.9% for unsuccessful attempts to quit, 13.2% use despite negative consequences, 12.9% time spent using, and 5.9 % neglecting activities.

Latency to the initial DSM-IV criterion

The latency from onset of tobacco use to onset of a criterion varied by criterion. There was a slight trend for the most prevalent criteria to be experienced within the shortest period of time; it took at least ten months after tobacco use onset for the appearance of the first criterion. The shortest latency was for tolerance (x̄=10.3 months, SD=9.0), the longest for a great deal of time spent using tobacco (x̄=13.8 months, SD=9.5). The latencies for time using unsuccessful attempts to quit (x̄=12.8 months, SD=9.2), and using despite negative consequences (x̄=13.5 months, SD=8.8) were statistically significantly different from latency to tolerance. Average latencies were 11.3 months (SD=8.8) for impaired control, 12.1 months (SD=9.1) withdrawal, and 12.6 months (SD=9.3) neglecting activities.

Pairwise comparisons of onset order among the four DSM-IV criteria

Among adolescents who experienced any of the seven DSM-IV criteria, 92% experienced one of the four criteria selected for analysis. The majority (76.6%) experienced only one criterion in the first symptomatic month, 18.6% experienced two criteria, 3.3% experienced 3 criteria. Seventy-three percent experienced tolerance and/or impaired control in the first symptomatic month. Three cases who reported four criteria in that month were excluded from the analysis.

To identify stages of progression, we calculated the order in which each criterion in a pair had been experienced first. When two or three criteria were experienced in the same month (ties), an order among them was assumed based on the order observed among adolescents who first experienced these two criteria in different months. Table 1 presents the proportions who experienced each criterion first for cases who experienced at least one criterion and those who experienced both criteria in a pair. If only one criterion had been experienced, it was counted as occurring first. The first proportions reflect differences in the probabilities of occurrence of criteria; the second proportions indicate ordering propensities, with no confounding due to differences in probabilities of occurrence.

Table 1.

Pairwise comparison of the order of onset of four criteria of DSM-IV nicotine dependence for those who experienced at least one DSM-IV criterion or both criteria by W5 among new tobacco users (W1-W5, N=181)

| Onset order |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among youths who experienced at least one DSM-IV criteriona |

Among youths who experienced both DSM-IV criteria |

||||||||

| Criterion A | Criterion B | A first (no ties) (%) |

A&B Same month (%) |

A first (ties)b (%) |

N | A first (no ties) (%) |

A&B Same month (%) |

A first (ties)b (%) |

N |

| Tolerance | Impaired control | 45.3 | 10.4 | 50.5 | (169) | 41.0 | 19.8 | 51.1 | (83) |

| Tolerance | Withdrawal | 61.2 | 8.5 | 66.9 | (155) | 56.4 | 18.0 | 68.8 | (71) |

| Tolerance | Unsuccessful attempts to quit |

78.7 | 2.1 | 80.4 | (143) | 64.3 | 7.5 | 69.5 | (41) |

| Impaired Control | Withdrawal | 52.7 | 13.7 | 61.0 | (152) | 38.3 | 27.1 | 53.3 | (74) |

| Impaired Control | Unsuccessful attempts to quit |

79.4 | 11.9 | 90.1 | (129) | 55.2 | 28.5 | 77.1 | (55) |

| Withdrawal | Unsuccessful attempts to quit |

67.3 | 5.4 | 70.1 | (115) | 43.8 | 14.6 | 51.3 | (43) |

If only one criterion was experienced, it was counted as occurring first.

Includes ties distributed as per order of non-tied responses among those who first experienced each criterion in a different month.

There are six potential sequences. The proportion who experienced one criterion prior to the other (among youths who experienced both criteria in a pair) ranged from 51.1% to 77.1%. The strongest order was between impaired control and unsuccessful attempts to quit; the next two strongest sequential patterns were tolerance prior to withdrawal and unsuccessful attempts to quit. There did not appear to be any order between tolerance and impaired control, impaired control and withdrawal, or withdrawal and unsuccessful attempts to quit.

Test of sequential models for male and female adolescents

To identify stages of progression beyond pairwise comparisons of two events, the analytical strategy outlined above was implemented by gender. The tests examined whether specific sequences were necessary in the progression, except for individuals who progressed randomly with no systematic order. The baseline Model 0 assumed independence and no ordering among criteria.

Based on the observed pairwise comparisons, alternate specifications of sequences of progression in DSM-IV criteria were tested against the baseline model. Combinations of criteria were examined two, three and four at a time. At each step, the best fitting model identified in the prior step was taken as the starting model for the next modification. First, all combinations of the two earliest criteria (tolerance, impaired control) were assumed to precede each of the two subsequent criteria (withdrawal, unsuccessful attempts to quit). Given four criteria, 24 models could be tested. Four models were tested for withdrawal (Models 1A-1D), assuming that withdrawal was preceded by: (1) either tolerance or impaired control (1A); (2) only tolerance (1B); (3) only impaired control (1C); (4) both tolerance and impaired control (1D). Parallel sequences were tested for unsuccessful attempts to quit (Models 2A-2D). Of Models 1, Model 1D fit the data best for both genders. Of Models 2, Model 2D fit best for males; Models 2C and 2D fit equally well for females (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sequential models of DSM-IV criteria for males and females among new tobacco users by Wave 5 (N=350)

| Male (N=150) |

Female (N=200) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Models | df | ||

| Model 0 (independence model) | 60 | 194.73 | 234.98 |

| Models 1- Tolerance or impaired control before withdrawal | |||

| 1A. Tolerance or impaired control before withdrawal | 16 | 19.05 | 12.30 |

| 1B. Tolerance before withdrawal | 25 | 26.62 | 22.50 |

| 1C. Impaired control before withdrawal | 25 | 30.85 | 19.82 |

| 1D. Tolerance and impaired control before withdrawal | 34 | 38.19 | 30.85 |

| Models 2- Tolerance or impaired control before attempts to quit | |||

| 2A. Tolerance or impaired control before attempts to quit | 16 | 5.99 | 10.40 |

| 2B. Tolerance before attempts to quit | 25 | 14.36 | 28.04 |

| 2C. Impaired control before attempts to quit | 25 | 11.02 | 14.82 |

| 2D. Tolerance and impaired control before attempts to quit | 34 | 18.52 | 31.27 |

| Models 3- Combined best fitting models of Models 1 and 2 | |||

| 3A. (1D+2D) Tolerance and impaired control before withdrawal and attempts to quit |

47 | 48.19 | 55.49 |

| 3B. (1D+2C) Tolerance and impaired control before withdrawal, impaired control before attempts to quit |

44 | 37.45 | |

|

Models 4- Modifications of Model 2D for males and Model 3B for females in the order between withdrawal and attempts to quit |

|||

| 4A. Model 2D+ withdrawal before attempts to quit | 38 | 22.54 | |

| 4B. Model 2D+ attempts to quit before withdrawal | 51 | 50.23 | |

| 4C. Model 3B+ attempts to quit before withdrawal | 48 | 43.25 | |

|

Models 5- Modifications of Model 4A for males in the order between withdrawal and impaired control |

|||

| 5A. Model 4A+ withdrawal before impaired control | 48 | 33.94 | |

| 5B. Model 4A+ impaired control before withdrawal | 48 | 46.85 | |

|

Models 6- Modifications of Model 5A for males and Model 4C for females in the order between tolerance and impaired control |

|||

| 6A. Model 5A+ tolerance before impaired control | 51 | 40.11 | |

| 6B. Model 5A+ impaired control before tolerance | 55 | 64.00 | |

| 6C. Model 4C+ impaired control before tolerance | 52 | 62.12 | |

|

Models 7- Modifications of Model 6A for males in the order between tolerance and withdrawal |

|||

| 7A. Model 6A+ tolerance before withdrawal | 55 | 49.22 | |

| 7B. Model 6A+ withdrawal before tolerance | 55 | 63.57 | |

While a maximum of 16 models could theoretically be fitted from the combinations of Models 1 and 2, only the best fitting models from each set needed to be considered, one for males and two for females (Models 3). Combined Model 3A (1D + 2D) was tested for males and females against the single best-fitting models 1D and 2D; combined Model 3B (1D + 2C) was tested against 1D and 2C for females. For males, the best fitting model overall was Model 2D (tolerance and impaired control before unsuccessful attempts to quit). For females, the best fitting model was Model 3B (1D + 2C) (tolerance and impaired control before withdrawal and impaired control before unsuccessful attempts to quit). Model 2D fit the data for 94.2% of males (93.3% not by chance); Model 3B fit the data for 75.2% of females (67.2% not by chance). These models fit the data better than the baseline model.

To test the full sequence among the four criteria, four modifications, which tested alternate sequential orders between pairs of criteria, were added to these models (See Table 2 for detailed specifications of the models). Three models (Models 4) tested modifications in the order between withdrawal and unsuccessful attempts to quit: (1) withdrawal precedes unsuccessful attempts to quit (4A); (2) unsuccessful attempts to quit precedes withdrawal (4B, 4C). Model 4A significantly improved the fit of Model 2D for males; Model 4C improved the fit of Model 3B for females.

Two models (Models 5) tested modifications in the order between impaired control and withdrawal: (1) withdrawal precedes impaired control (5A); (2) impaired control precedes withdrawal (5B). These modifications could not be applied to females since Model 4C for females established that impaired control preceded withdrawal. Model 5A improved the fit of Model 4A.

Three models (Models 6) tested modifications in the order between tolerance and impaired control: (1) tolerance precedes impaired control (6A); (2) impaired control precedes tolerance (6B, 6C). Model 6A provided a better fit than Model 5A for males, 6B did not fit. Model 6C provided a worse fit than Model 4C for females, suggesting that no order existed between tolerance and impaired control.

Two models (Models 7) tested modifications in the order between tolerance and withdrawal for males: (1) tolerance precedes withdrawal (7A); (2) withdrawal precedes tolerance (7B). Model 7A provided a better fit than model 6A; 7B did not fit. However, Model 7A provided a worse fit than Model 5A.

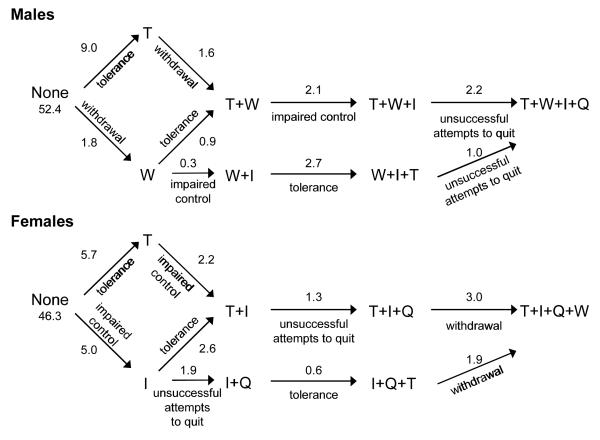

Thus, for males, the best fitting model is Model 5A (Figure 1), which characterizes 74.1% of males (66.0% not by chance):

Tolerance and withdrawal or withdrawal by itself precede impaired control

Tolerance or impaired control precedes unsuccessful attempts to quit

Figure 1.

Proportions of scale-type individuals who followed specific pathways among males and females (New tobacco users by Wave 5, N=350)

Note: T-tolerance; I-impaired control; W-withdrawal, Q-unsuccessful attempts to quit The model accounts for 74.1% of males (66.0% not by chance) and 70.6% of females (65.7% not by chance)

For females, the best fitting model is Model 4C, which characterizes 70.6% of females (65.7% not by chance):

Tolerance and impaired control or impaired control by itself precede unsuccessful attempts to quit

Unsuccessful attempts to quit precedes tolerance

Unsuccessful attempts to quit or tolerance precedes withdrawal.

Test of sequential models for different racial/ethnic groups

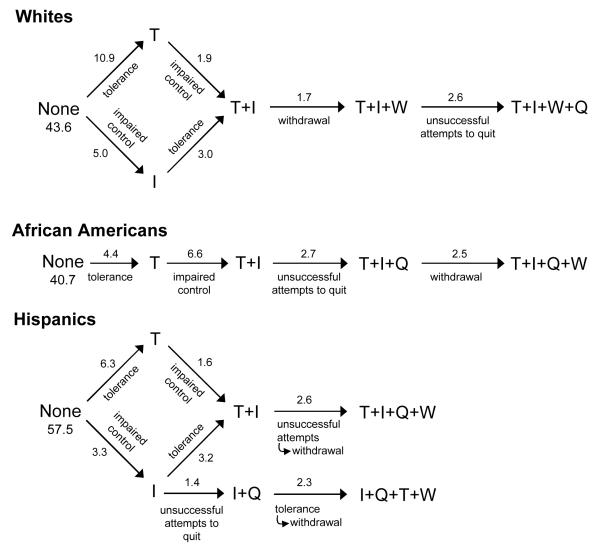

A similar analysis was applied to each racial/ethnic group. The steps in model testing are specified in Table 3. For white adolescents, the best fitting model is Model 4D, which characterizes 68.7% of whites (60.6% not by chance) (Figure 2):

Tolerance and impaired control precede withdrawal

Withdrawal precedes unsuccessful attempts to quit

Table 3.

Sequential models of DSM-IV criteria for Whites, African Americans, and Hispanics among new tobacco users by Wave 5 (N=350)

| Whites (N=101) |

African Americans (N=91) |

Hispanics (N=158) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Models | df | |||

| Model 0 (independence model) | 60 | 141.86 | 135.56 | 179.92 |

|

Models 1- Tolerance or impaired control before

withdrawal |

||||

| 1A. Tolerance or impaired control before withdrawal | 16 | 7.80 | 11.11 | |

| 1B. Tolerance before withdrawal | 25 | 17.47 | 16.43 | 11.85 |

| 1C. Impaired control before withdrawal | 25 | 16.45 | 22.07 | 12.00 |

| 1D. Tolerance and impaired control before withdrawal | 34 | 26.13 | 26.32 | 15.33 |

|

Models 2- Tolerance or impaired control before

attempts to quit |

||||

| 2A. Tolerance or impaired control before attempts to quit |

16 | 9.73 | 2.31 | 7.68 |

| 2B. Tolerance before attempts to quit | 25 | 18.16 | 9.40 | 33.09 |

| 2C. Impaired control before attempts to quit | 25 | 13.93 | 9.23 | 9.16 |

| 2D. Tolerance and impaired control before attempts to quit |

34 | 22.92 | 15.82 | 36.04 |

|

Models 3- Combined best fitting models of Models 1

and 2 |

||||

| 3A. (1D+2D) Tolerance & impaired control before withdrawal and attempts to quit |

47 | 37.37 | 33.95 | |

| 3B. (1D +2C) Tolerance & impaired control before withdrawal, impaired control before attempts to quit |

44 | 23.94 | ||

|

Models 4- Modifications of Model 3A for whites and African Americans and Model 3B for Hispanics in the order between withdrawal and attempts to quit |

||||

| 4D. Model 3A + withdrawal before attempts to quit | 51 | 39.91 | 42.86 | |

| 4E. Model 3A + attempts to quit before withdrawal | 51 | 41.24 | 37.98 | |

| 4C. Model 3B + attempts to quit before withdrawal | 48 | 29.22 | ||

|

Models 6- Modifications of Model 4D for whites, Model 4E for African Americans, and Model 4C for Hispanics in the order between tolerance and impaired control |

||||

| 6D. Model 4D + tolerance before impaired control | 55 | 49.81 | ||

| 6E. Model 4D + impaired control before tolerance | 55 | 59.62 | ||

| 6F. Model 4E + tolerance before impaired control | 55 | 41.63 | ||

| 6G. Model 4E + impaired control before tolerance | 55 | 51.75 | ||

| 6C. Model 4C + impaired control before tolerance | 52 | 43.01 | ||

Figure 2.

Proportions of scale-type individuals who followed specific pathways among racial/ethnic groups (New tobacco users by Wave 5, N=350)

Note: T-tolerance; I-impaired control; W-withdrawal, Q-unsuccessful attempts to quit The model accounts for 68.7% (60.6% not by chance), 56.8% (50.7% not by chance) and 78.1% (68.8% not by chance) of white, African American, and Hispanic adolescents, respectively.

For African Americans, the best fitting model is Model 6F, which characterizes 56.8% of African Americans (50.7% not by chance):

Tolerance precedes impaired control

Impaired control precedes unsuccessful attempts to quit

Unsuccessful attempts to quit precedes withdrawal.

The sequencing order (Model 4C) for Hispanics is more complex than for African Americans and is the same as for females. It characterizes 78.1% of Hispanics (68.8% not by chance):

Tolerance and impaired control or impaired control by itself precede unsuccessful attempts to quit

Unsuccessful attempts to quit precedes tolerance

Unsuccessful attempts to quit or tolerance precedes withdrawal

Discussion

Little is known about the nature of the first symptoms of ND and the sequence of subsequent symptoms in adolescence. We attempted to delineate developmental sequences of onset among the four most prevalent criteria of DSM-IV ND: tolerance, impaired control, withdrawal, and unsuccessful attempts to quit. We did not consider use despite negative consequences, time spent using, or neglecting activities to be able to use, since these criteria were reported less frequently than the other four and the complexity of sequencing analysis increases greatly with increasing number of events to be ordered. We examined sequences by gender and race/ethnicity.

The order of onset across criteria varied by gender and race/ethnicity. The proportion of tobacco users who could be classified as following an order not by chance ranged from 50.7% to 68.8%. The proportion was the same for males and females; it was the lowest among African Americans and the highest among Hispanics. Multiple pathways were more common than single pathways. For most adolescents, tolerance appeared first, although for a substantial minority the first criterion was impaired control. Tolerance appeared before withdrawal; impaired control appeared before attempts to quit. However, there were variations in these patterns and additional symptoms could intervene between symptoms in a pair. For males, withdrawal was experienced first or second, while for females, it was experienced last. Each racial/ethnic group had its own pattern. For all three groups, the major path was one in which tolerance was experienced first, although for whites and Hispanics, an alternate path began with impaired control. The last experienced criterion was unsuccessful quit attempts among whites, but withdrawal among African Americans and Hispanics. Two reasons may account for the facts that the model provided more explanatory power for Hispanics than the other two groups. A larger proportion of Hispanics than others reported no symptoms, the first stage in the progression. In addition, Hispanics who reported symptoms exhibited a larger number of distinct patterns of progression than whites or African Americans. More complicated patterns allow for a larger proportion of individuals to be classified in a particular scale type. By contrast, African Americans had a simpler structure. We could not identify for them any significant minor patterns, those who did not follow the major pattern appeared to do so randomly.

Since extensiveness of smoking is highly associated with ND [4], sequencing of criteria might differ among regular smokers and experimenters. However, the analysis could not be implemented separately for groups that differed in extensiveness of use, since this distinction could reflect a consequence of cigarette use, an endogenous variable of ND. When analyzing a sequential pattern, the selection of the sample should not be controlled by the state of an endogenous variable.

A limitation of the study is potential left censoring resulting from sample selection, and right censoring resulting from the truncation of observations. Youths who initiated the use of tobacco products more than one year prior to the survey, especially at younger ages, were not included. Left censoring can be a source of bias, if those who manifest dependence symptoms early have different progression patterns than those who develop symptoms later. There is potentially right censoring since some smokers will develop symptoms of ND and some youths will start to smoke after the last interview. A longer period of observation will increase the proportion of persons who reach the latter stages. Right censoring will affect the composition of individuals who follow various progression stages but not necessarily the progression patterns themselves— unless the future progression patterns of censored cases are different from those already observed among the non-censored cases. The extent of censoring cannot be determined from our data. One would need additional follow-ups of subjects past the period of risk to resolve the issue of right censoring and data on younger subjects to resolve the issue of left censoring. The extent to which the sequences observed in this sample can be replicated remains also to be determined. In addition, further research is needed on how sequential patterns might vary depending up on age of onset into tobacco use.

The identification of sequences among criteria implies increasing degree of dependence severity. An earlier symptom in the sequence is probably a less severe indicator of dependence than a later one. The multiplicity of patterns argues against a clear ranking in order of severity early in the process of addiction, except for tolerance, which generally tends to be reported first. Ranking in order of severity may differ at different stages of dependence, as suggested by the findings of a psychometric analysis conducted on data from current smokers in our study [24] which ascertained based on item response theory [25] the degree to which the DSM-IV items mapped into an underlying dimension of severity of ND. The data fit a unidimensional model. The suggested order of increasing severity among the criteria was impaired control, tolerance, withdrawal, unsuccessful attempts to quit, great deal of time spent using tobacco, using despite negative consequences, and neglecting activities because of use. Strong et al. [24] did not test for alternate pathways. Most importantly, ordering in severity among current smokers may differ from the developmental ordering among new smokers. The four criteria examined in this study at the earliest stage of dependence, and particularly the two earliest criteria — tolerance and impaired control - are also among the four least severe criteria in the assumed unidimensional order observed among current smokers. However, while impaired control ranked as the least severe in Strong et al. [24], the present analysis documents that tolerance was experienced first more frequently than impaired control.

The prevalence and sequence of symptoms observed in this sample fit our understanding of the neuropharmacology of ND [10]. Tobacco products deliver nicotine to the brain, where it binds to nicotinic cholinergic receptors and facilitates the release of neurotransmitters. As stressed by Benowitz [10]: “Chronic nicotine exposure results in neuroadaptation, that is, the development of tolerance. When a person stops smoking, the absence of nicotine results in a subnormal release of dopamine and other neurotransmitters. Thus, nicotine withdrawal results in the state of deficient dopamine responses to novel stimuli”(p. 533). The sequence of initial symptoms of dependence reported by adolescent smokers in this study follows a general pattern consonant with this underlying neurobiological process and supports the importance of physiological factors in the earliest stages of the development of ND.

Acknowledgements

This research was partially supported by research grants DA12697 from NIDA/NCI and ALF CU51672301A1 from the American Legacy Foundation (Denise Kandel, Principal Investigator), and a Research Scientist Award (DA00081) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to Denise Kandel. The authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Portions of this paper were presented at the 14th Annual Meeting of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, Portland, Oregon, February 2008.

References

- 1.DiFranza JR. Hooked from the first cigarette. Sci Am. 2008;298:82–87. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0508-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, Ockene JK, McNeill AD, Coleman M, et al. Development of symptoms of tobacco dependence in youths: 30 month follow up data from the DANDY study. Tob Control. 2002;11:228–235. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiFranza JR, Savageau JA, Fletcher K, O’Loughlin J, Pbert L, Ockene JK, et al. Symptoms of tobacco dependence after brief intermittent use: the development and assessment of nicotine dependence in youth-2 study. Arch Pediatr Adoles. 2007;161:704–710. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.7.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandel DB, Hu M, Griesler P, Schaffran C. On the development of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:26–39. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karp I, O’Loughlin J, Hanley J, Tyndale RF, Paradis G. Risk factors for tobacco dependence in adolescent smoking. Tob Control. 2006;15:199–204. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.014118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tarasuk J, Meshefedjian G, McMillan-Davey E, Paradis G, et al. Assessment of nicotine dependence symptoms in adolescents: a comparison of five indicators. Tob Control. 2002;11:354–360. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.4.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Loughlin J, DiFranza J, Tyndale RF, Meshefedjian G, McMillan-Davey E, Clarke PB, et al. Nicotine-dependence symptoms are associated with smoking frequency in adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gervais A, O’Loughlin J, Meshefedjian G, Bancej C, Tremblay M. Milestones in the natural course of cigarette use onset in adolescents. CMAJ. 2006;175:255–261. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu M, Muthen B, Schaffran C, Griesler P, Kandel DB. Developmental trajectories of criteria of nicotine dependence in adolescence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008;98:94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benowitz NL. Clinical pharmacology of nicotine: implications for understanding, preventing, and treating tobacco addiction. Clin Pharmacol Therapeutics. 2008;83:531–541. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koob G, Kandel DB, Volkow ND. Psychiatric Pathophysiology: Addiction. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J, First MB, Maj M, editors. Psychiatry. 3rd ed John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2008. pp. 354–378. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Baker TB. Assessing tobacco dependence: a guide to measure evaluation and selection. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8:339–351. doi: 10.1080/14622200600672765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shadel WG, Shiffman S, Niaura R, Nichter M, Abrams DB. Current modesl of nicotine dependence: what is known and whis is needed to advance understanding of tobacco etiology among youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:S9–S21. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed American Psychiatric Association; Washington: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pierce JP, Choi WS, Gilpin EA, Farkas AJ. Validation of susceptibility as predictor of which adolescents take up smoking in the United States. Health Psychol. 1996;15:355–361. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dierker LC, Donny E, Tiffany S, Colby SM, Perrine N, Clayton RR. The association between cigarette smoking and DSM-IV nicotine dependence among first year college students. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;86:106–14. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sledjeski EM, Dierker LC, Costello D, Shiffman S, Donny E, Flay BR, et al. Predictive validity of four nicotine dependence measures in a college sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;87:10–19. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kandel DB, Schaffran C, Griesler P, Samuolis J, Davies M, Galanti MR. On the measurement of nicotine dependence in adolescence: comparisons of the FTND and a DSM-IV based scale. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30:319–332. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of drug involvement, examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kandel DB, Yamaguchi K, Chen K. Stages of progression in drug involvement from adolescence to adulthood: further evidence for the gateway theory. J Stud Alcohol. 1992;53:447–457. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. Patterns of drug use from adolescence to young adulthood: II. Sequences of progression. Am J Public Health. 1984;74:668–672. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.7.668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. Parametric event sequence analysis: An application to an analysis of gender and racial/ethnic differences in patterns of drug-use progression. J Am Statistical Association. 1996;91:1388–1399. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamaguchi K, Kandel DB. Log linear sequence analyses, gender and racial/ethnic differences in drug use progress. In: Kandel DB, editor. Stages and pathways of drug involvement, examining the gateway hypothesis. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strong DR, Kahler CW, Colby SM, Griesler PG, Kandel DB. Linking measures of adolescent nicotine dependence to a common latent continuum. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:296–308. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strong DR, Kahler CW, Abrantes AM, MacPherson L, Myers MG, Ramsey SE, et al. Nicotine dependence symptoms among adolescents with psychiatric disorders: using a Rasch model to evaluate symptom expression across time. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:557–569. doi: 10.1080/14622200701239563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]