Abstract

Linker for activation of T cells (LAT) is a dually palmitoylated transmembrane adaptor protein essential for T cell development and activation. However, whether LAT palmitoylation and/or lipid raft localization are required for its function is controversial. To address this question, we used a combination of biochemical, imaging, and genetic approaches, including LAT retrovirus-transduced mouse T cells and bone marrow chimeric mice. A nonpalmitoylated, non-lipid raft-residing mutant of transmembrane LAT could not reconstitute T cell development in bone marrow chimeric mice. This mutant was absent from the plasma membrane (PM) and was restricted mainly to the Golgi apparatus. A chimeric, nonpalmitoylated LAT protein consisting of the PM-targeting N-terminal sequence of Src kinase and the LAT cytoplasmic domain (Src-LAT) localized as a peripheral membrane protein in the PM, but outside lipid rafts. Nevertheless, Src-LAT restored T cell development and activation. Lastly, monopalmitoylation of LAT on Cys26 (but not Cys29) was required and sufficient for its PM transport and function. Thus, the function of LAT in T cells requires its PM, but not raft, localization, even when expressed as a peripheral membrane protein. Furthermore, LAT palmitoylation functions primarily as a sorting signal required for its PM transport.

Proteins can be modified with fatty acids in several different ways, including palmitoylation. This particular modification refers to the covalent, and usually reversible, attachment of palmitate to cysteine residues. In most cases, palmitate is attached to the protein posttranslationally through a reversible thioester bond (S-palmitoylation), but to date there is no known consensus site for palmitoylation. Although initially thought to serve the function of simply anchoring proteins in the cell membrane, palmitoylation is now known to occur in a wide variety of proteins (e.g., ∼50 in yeast), including peripheral and integral membrane proteins. Palmitoylation is also involved in protein trafficking, localization, and function, and palmitoylated proteins are known to play important roles in various cellular signal transduction pathways (1, 2). Despite the fact that protein palmitoylation was first documented more than 25 years ago, only recently has the pace of discovery in this field accelerated due to several developments, particularly the identification of a large (∼23-member) novel family of mammalian protein acyl transferases (PATs)3 (3) that mediate the palmitoylation of various proteins (3). To date, however, very little is known about the mechanisms that regulate the function, localization, and substrate specificity of these PATs. One of the best examples of the importance of protein palmitoylation in signaling pathways is provided by immune receptor-mediated signaling, particularly the Ag-specific TCR. Although none of the subunits of the TCR complex itself is palmitoylated, substantial numbers of signaling enzymes and adaptor proteins are modified by palmitoylation (4), including positive regulators of signaling such as the CD4 and CD8β coreceptors, the Src-family kinases Lck and Fyn, and the adaptor protein linker for activation of T cells (LAT), or negative regulators such as the adaptor protein PAG/Cbp. In most cases, the palmitoylation of these signaling proteins (and others) was found to be essential for their proper signaling function as evidenced by mutagenesis studies and, in some cases, by using 2-bromopalmitate, a synthetic inhibitor of protein palmitoylation (5). Nevertheless, the processes and enzymes that regulate the dynamic process of protein palmitoylation in hematopoietic cells, including T cells, remain elusive.

LAT, a 36- to 38-kDa transmembrane (TM) protein, belongs to the family of TM adaptor proteins (TRAPs) (6) and is expressed in T, NKT, NK, pre-B, and mast cells and in platelets (7). Upon receptor triggering, LAT is phosphorylated on several cytoplasmic tyrosine residues, primarily by Syk-family kinases (e.g., ZAP-70 in T cells), whereupon it functions as an adaptor to directly or indirectly recruit other signaling proteins such as PLCγ1, SLP-76, Grb2, and Gads. Analysis of Lat−/− mice and LAT-deficient Jurkat T cell lines (J.CaM2 and ANJ3) showed that T cell development and the activation of peripheral T cells depend on LAT (8, 9).

In the absence of LAT, the activation of several TCR-stimulated signaling pathways, including Ca2+ mobilization, Tyr phosphorylation of PLCγ1, Vav, and SLP-76, CD69 up-regulation, and activation of the MAPK ERK, Ras, the transcription factors AP-1 and NFAT, and the Il-2 gene promoter, are greatly impaired (8, 10). Hence, LAT is considered to function as a critical scaffold protein that assembles TCR-coupled enzymes and adaptors essential for T cell development and activation.

Similar to other TRAPs (e.g., PAG/Cbp, LIME and NTAL/LAB), LAT is dually palmitoylated on cysteine residues, in this case Cys26 and Cys29, which are localized intracellularly adjacent to the TM domain of LAT (6). As a result of this palmitoylation, LAT is localized in lipid rafts and in their corresponding biochemically defined cellular fraction, that is, detergent-resistant membranes (DRMs) (11). However, the importance of raft localization for the proper function of LAT is controversial. Thus, it was initially reported that cysteine-mutated, nonpalmitoylated LAT mutants cannot reconstitute TCR signaling in LAT-deficient Jurkat cells (10, 12), leading to the conclusion that the localization of LAT in lipid rafts is essential for its function. In apparent contrast to this finding, analysis of a LAT fusion protein consisting of the extracellular and TM region of the LAT-related TRAP, linker for activation of X cells (LAX), and the cytoplasmic domain of LAT, revealed that this nonpalmitoylated chimeric LAT protein was functional in LAT-deficient Jurkat cells and restored T cell development when expressed as a transgene under control of the CD2 promoter in Lat−/− mice, despite not being localized in lipid rafts (13). To further explore this apparent contradiction and follow the fate and function of nonpalmitoylated LAT, we analyzed in detail the localization and function of cysteine-mutated native LAT, or a LAT chimera (Src-LAT), expressed as a peripheral membrane protein targeted to the plasma membrane (PM) by the N-terminal region of the Src kinase. Here, we confirm that nonpalmitoylated transmembrane LAT is retained in intracellular compartment(s), primarily the Golgi apparatus. Furthermore, our results reveal, first, that Cys26 (but not Cys29) is essential for transporting LAT from the Golgi to the PM and, second, that PM-targeted Src-LAT, despite the fact that it is not an integral membrane protein and is absent from lipid rafts, fully restores T cell development and activation. Thus, we conclude that the mere targeting of LAT to the PM is sufficient for its function, irrespective of its lipid raft localization.

Materials and Methods

Mice, Abs, and other reagents

C57BL/6 (B6) and Lat−/− mice on a B6 background (9) were bred and maintained in our animal facility. Animal experiments were performed according to American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care guidelines and approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Hamster anti-mouse CD3ε (145-2C11) and anti-mouse CD28 (37.51) and anti-phospho-Tyr (pY; 4G10) mAbs were purified from hybridoma supernatants. Rabbit anti-phospho-LAT (Y191) Ab, rabbit anti-LAT (used for flow cytometry), and mouse anti-phospho-p44/42 (ERK1/2) MAPK (T202/Y204; E10) mAbs were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. The rabbit anti-LAT Ab used for immunoblotting was from Millipore. Unconjugated rat anti-mouse CD4 (RM4-5), rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (2.4G2), rat anti-mouse IL-4 (11B11), and mouse anti-GM130 (35) mAbs were from BD Biosciences. The allophycocyanin- and PE-conjugated hamster anti-mouse TCRβ (H57-597), PE-conjugated and biotinylated rat anti-mouse CD4 (RM4-5), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD8α (53-6.7), PE-conjugated and biotinylated hamster anti-mouse CD3ε (145-2C11), allophycocyanin-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD19 (6D5), PE-conjugated mouse anti-mouse NK1.1 (PK136), and PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (XMG1.2) mAbs were from BioLegend. Mouse anti-Myc mAb (9E10), rabbit anti-ERK1/2 (C-16), rabbit anti-Grb2 (C-23), and rabbit anti-PLCγ1 Ab (1249) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse anti-actin (C4) mAb was purchased from MP Biomedicals. HRP-conjugated cholera toxin B subunit and streptavidin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All cytokines were obtained from Pepro-Tech, and Staphylococcus enterotoxin E (SEE) was from Toxin Technology.

Vectors

The retroviral vector pMIGII was a gift from Dr. D. Vignali (14). LAT-wild-type (wt)-GFP and LAT-C26/29A-GFP cDNAs in the pMX vector have been described previously (15) and were subcloned into pMIGII, thereby removing the IRES-GFP element from pMIGII. The new vectors were designated pMII-LATwt-GFP and pMII-LAT-C26/29A-GFP. pCEFL vectors encoding LATwt, LATC26A, LAT-C29A, and LAT-C26/29A (all with a C-terminal Myc tag) were provided by Dr. L. Samelson (10), and the LAT cDNAs were subcloned into pMIGII by PCR using the restriction sites EcoRI and XhoI to generate pMIGII-LATwt, -LAT-C26A, -LAT-C29A, and -LAT-C26/29A. LATwt was similarly subcloned into the pcDNA3 vector (pcDNA3-LATwt). Src-LAT was constructed by PCR amplification of Src kinase amino acids 1–20 (using KpnI and BamHI restriction sites) and LAT (amino acids 34–233 plus a C-terminal Myc-tag, using BamHI and XhoI restriction sites), and subcloned into pMIGII, pcDNA3, and pMII (pMIGII-Src-LAT, pcDNA3-Src-LAT, and pMII-Src-LAT-GFP, respectively). The sequences of all inserts were verified by sequencing (Eton Bioscience).

Cell culture

J.CaM2 cells, a LAT-deficient mutant of Jurkat cells, were obtained from Dr. A. Weiss (8). Raji B lymphoblastoid cells (CCL-86) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. J.CaM2 and Raji cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The ecotropic packaging cell line Plat-E was obtained from T. Kitamura (16) and was maintained in DMEM containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, penicillin (100 U/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml), puromycin (1 μg/ml), and blasticidin (10 μg/ml). Mouse CD4+ T cells were enriched from lymph node and spleen cell suspensions by negative selection using magnetic beads (Stem-Cell Technologies). More than 95% of the resulting cells were CD4+. For biochemical analysis, thymocytes were incubated on ice for 30 min with biotinylated anti-CD3ε plus biotinylated anti-CD4 mAbs (10 μg/ml each) and then stimulated with streptavidin (20 μg/ml) at 37°C for 1 min. Peripheral CD4+ T cells were incubated on ice for 20 min with anti-CD3ε plus anti-CD28 mAbs (20 μg/ml each) or with control hamster IgG (40 μg/ml). After washing, the cells were stimulated with a crosslinking anti-hamster IgG Ab (30 μg/ml; Pierce) at 37°C for 2 min. For Th1 differentiation, cells were cultured in 24-well plates (2 × 106 cells/well) coated with anti-CD3ε (1.5 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) in a total volume of 1 ml of culture medium (RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 55 μM 2-ME, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) in the presence of 10 ng/ml IL-12 and 5 μg/ml anti-IL-4. After 1 wk, cells were washed and restimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 for 6 h in the presence of 5 μg/ml brefeldin A. IFN-γ expression was analyzed by intracellular staining (ICS; see below).

Transient transfection, retroviral transduction, and bone marrow (BM) chimeras

For transient transfection, 5 × 106 Jurkat cells in 400 μl of RPMI 1640 were electroporated with 10 μg of DNA at 250 V, 950 μF using the Bio-Rad Gene Pulser electroporator. Cells were analyzed 16–48 h later by fluorescence microscopy.

Plat-E cells were transfected with retroviral vectors using TransIT-LT1 (Mirus Bio), and the virus containing supernatant was harvested after 48 and 72 h. Mouse CD4+ T cells were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3ε (1.5 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 (2 μg/ml) in complete RPMI 1640 medium containing IL-2 (10 ng/ml). After 24 and 48 h, T cells were infected with virus-containing supernatant containing 5 μg/ml polybrene (Sigma-Aldrich). Thirty percent to 60% of the T cells were routinely GFP-positive after the second infection, as determined by flow cytometry.

BM cells isolated from the femurs and tibia of Lat−/− donor mice (6–8 wk old) were cultured in DMEM containing 20% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 55 μM 2-ME, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), 10 mM HEPES, and 100 μM MEM nonessential amino acid solution, and supplemented with IL-3 (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (20 ng/ml), and stem cell factor (50 ng/ml). The cultured cells were infected twice after 24 and 48 h with virus as described above. Twenty percent to 30% of the BM cells were routinely GFP-positive. One day after the second infection, BM cells (1 × 106/mouse) were transferred by retroorbital injection into B6 recipient mice that were irradiated twice, at a 3-h interval, with 600 rad. BM chimeric mice were analyzed after 6–8 wk.

Flow cytometry

Peripheral blood lymphocytes, splenocytes, and thymocytes were resuspended in PBS/0.5% BSA. Nonspecific, Fc receptor-mediated Ab binding was blocked by preincubation with rat anti-mouse CD16/CD32 (0.25 μg/1 × 106 cells). Cells were surface stained with fluorochrome-conjugated Abs for 30 min on ice, washed, and then directly analyzed on a FACSCalibur or LSR II (BD Biosciences). For intracellular LAT staining, cells were first surface-stained with anti-CD4, fixed with 2% formalin for 10 min at 37°C, permeabilized with 90% methanol for 30 min on ice, and then indirectly stained with anti-LAT (1/200 in PBS/0.5% BSA) for 1 h at room temperature, followed by PE-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig (1/250) for 45 min at room temperature. For determination of intracellular IFN-γ expression by ICS, cells (1 × 106) were fixed, permeabilized, stained with 0.1 μg of PE-conjugated anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb (30 min on ice), and washed using the BD Cytofix/Cytoperm and BD Wash/Perm buffer (BD Biosciences) following the manufacturer's instructions. All flow cytometric data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star).

Digital microscopy

For fluorescence microscopy, cells (2 × 105) were attached to poly-l-lysine-coated slides, fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 10 min, and blocked with PBS/1% BSA for 30 min, all at room temperature. Cells were then incubated with anti-CD4 (1/100), anti-GM130 (1/500), anti-Myc (1/200), or anti-CD43 (1/20) for 1 h at room temperature, washed three times with PBS, incubated with Alexa Fluor 555 (1/300 in PBS/1% BSA), Alexa Fluor 488 (1/500), or Alexa Fluor 647 (1/100)-conjugated secondary Abs (Invitrogen) for 45 min, and finally mounted on slides with Vectashield containing 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories). Slides were examined using a Marianas digital microscopy workstation consisting of a Zeiss Axiovert 200M inverted microscope with Zeiss Plan-Apo 40 × 1.3 oil and 63 × 1.4 oil objectives, a Photometrics CoolSNAP HQ2 digital camera, and with SlideBook 4.2 software (Intelligent Imaging Innovations). Images were deconvoluted by the nearest neighbor method. Stacks of images were exported as TIFF files and further analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The plug-in Colocalisation Threshold was used to calculate the Pearson's correlation (Rtotal), where a value close to +1 indicates reliable colocalization and a value close to 0 represents random localization, and the percentage of green pixel intensities colocalized with red pixels (% green intensity (Int)) to estimate the percentage of LAT protein that localizes in the PM. This plug-in also generated frequency scatter plots, where the intensity of each pixel represents the frequency of pixels that display those particular green/red values. The RGB Profiler plug-in was used to generate line profiles of green and red pixel intensities from single images.

For immunological synapse (IS) analysis, Raji cells pulsed with 5 μg/ml SEE for 30 min at 37°C and washed were used as APCs. J.CaM2 cells transiently transfected with LATwt or Src-LAT were mixed with the SEE-pulsed Raji cells at a ratio of 1:1, and the mixture was transferred to poly-l-lysine-coated slides. After adherence for 20 min at 37°C, the cells were stained.

Immunoprecipitation, immunoblotting, and DRM isolation

For immunoprecipitation, cells were washed in ice-cold PBS and resuspended for 15 min in cold RIPA lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS, 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 2 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, and 10 μg/ml each aprotinin and leupeptin). Lysates were precleared with protein G-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) and then incubated with the indicated Ab (1 μg/sample) plus protein G-Sepharose. After shaking at 4°C overnight, the complexes were washed four times with lysis buffer, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted with Laemmli buffer containing 2-ME. Lysates or immunoprecipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). After blocking with 5% (w/v) dry milk in Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4°C with the indicated primary Ab, washed, and subjected to chemiluminescence detection with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG Ab using ECL (all from Amersham).

To isolate DRMs, T cells were lysed in 0.5 ml of MNE buffer (25 mM MES (pH 6.5), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 30 mM Na4P2O7, 1 mM Na3VO4, and protease inhibitors) containing 1% Triton X-100 for 30 min on ice, and dounced 15 times. Samples were centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatants were then mixed with 80% sucrose (0.5 ml) and transferred to Beckman ultracentrifuge tubes. Three milliliters of 30% sucrose, followed by 1 ml of 5% sucrose in MNE buffer, were overlaid. Samples were ultracentrifuged in a Beckman SW50Ti rotor (200,000 × g for 18 h at 4°C). Twelve fractions a 0.4 ml each were collected from the top of the gradient. Aliquots from each fraction were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with the indicated Abs.

Proliferation assay

CD4+ T cells (2 × 105/well) were cultured in Ab-coated 96-well flat-bottom plates for 3 days. Proliferation was assessed by [3H]thymidine uptake during the final 16 h of culture.

Results

T cell development depends on LAT palmitoylation

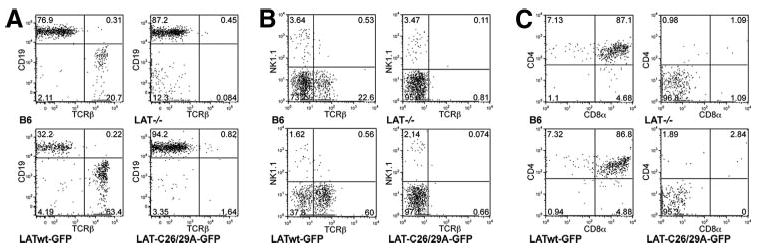

Palmitoylation of transfected LAT is required to reconstitute TCR signaling in LAT-deficient Jurkat cell lines (10, 12). However, it is unknown whether LAT palmitoylation is likewise necessary for T cell development. Therefore, we infected BM cells from Lat−/− mice with a retrovirus expressing a LATwt-GFP fusion protein that can become palmitoylated or with a nonpalmitoylated, cysteine-mutated LAT-C26/29A-GFP protein. Infected BM cells were then transferred into irradiated B6 mice and, 6 wk later, the reconstituted BM chimeras were analyzed for the reconstitution of different hematopoietic cell compartments. Non-reconstituted, Lat−/− mice and wt B6 mice were used as controls. TCRβ+ lymphocytes were detected in the peripheral blood of BM chimeric mice reconstituted with LATwt-GFP (and in normal B6 mice) but, similar to control Lat−/− mice, they were largely absent from BM chimeras reconstituted with LAT-C26/29A-GFP (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

LAT palmitoylation is required for T cell development. Lat−/− BM cells were infected with palmitoylated LATwt-GFP or nonpalmitoylated LAT-C26/29A-GFP and transferred into irradiated B6 mice. After 6 wk, blood (A), spleen (B), and thymus (C) were analyzed by flow cytometry, after gating on GFP+ cells. The difference in TCRβ staining intensity in lymphocytes from peripheral blood (A) and spleen (B) is due to the use of different fluorochromes. Untreated B6 and Lat−/− mice were used as controls. Diagrams are representative for one of four mice per group.

The proportion of CD19+TCRβ− B cells in the blood of LATwt-GFP (but not LAT-C26/29A)-reconstituted chimeric mice was always lower than in wt or Lat−/− B6 mice (32% vs 77% or 87%, respectively; Fig. 1A). This decrease most likely reflects the negative effect of LAT on B cell development. Indeed, during B cell development LAT is expressed in pre-B cells, but not in immature and mature B cells (17). LAT expression is down-regulated by pre-BCR activation at the pre-B cell stage and, similar to our findings, mice that express transgenic LAT in the B cell lineage show reduced numbers of peripheral B cells (18). Analysis of splenocytes of chimeric mice revealed a similar proportion (∼0.5%) of NKT (NK1.1+TCRβ+) cells in control B6 mice or LATwt-reconstituted BM chimeras, but a ∼5-fold reduced proportion (≤0.1%) in intact Lat−/− mice and in LAT-C26/29A-reconstituted chimeric mice. The LAT-C26/29A mutation, however, did not reduce the proportion of NK1.1+TCRβ− NK cells (Fig. 1B). Lastly, analysis of thymocytes from these mice indicated that the chimeric, LAT-C26/29A-GFP-reconstituted thymocytes displayed the same block in T cell development at the CD4−CD8− double-negative (DN) stage as did the intact Lat−/− thymocytes (Fig. 1C). In contrast, reconstitution with LATwt-GFP restored the DN thymocyte compartment to a level similar to that observed in intact B6 mice. Similar results were obtained with BM chimeras reconstituted with a LAT mutant, in which Cys26 and Cys29 were mutated to serine (LAT-C26/29S) instead of alanine (LAT-C26/29A; data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that, in contrast to wt LAT, the nonpalmitoylated LAT mutant was incapable of restoring T (and NKT) cell development. Thus, palmitoylation of intact LAT is required for T cell development.

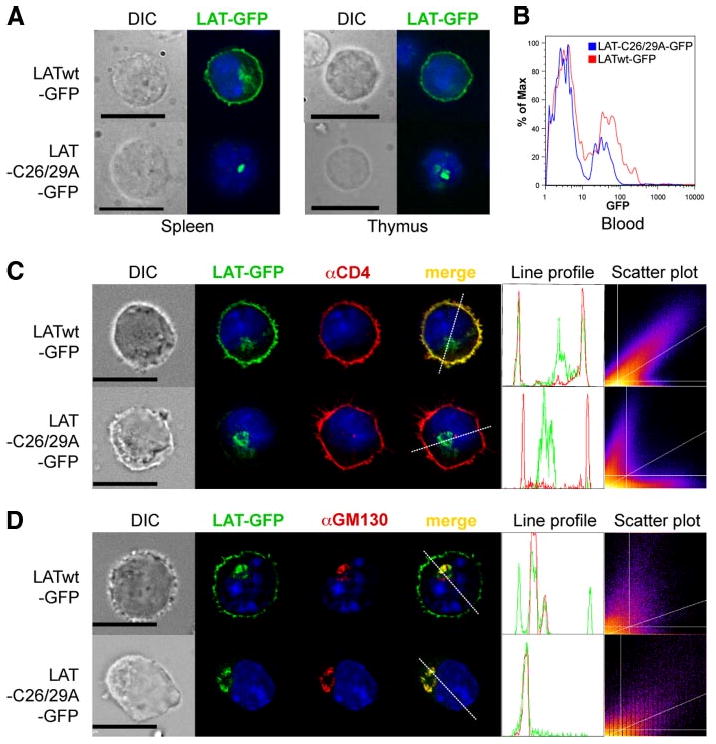

Nonpalmitoylated LAT is absent from the PM

The inability of cysteine-mutated LAT to restore T cell development seemed to suggest that the lipid raft localization of LAT is required for this process, as was initially concluded with regard to the importance of LAT palmitoylation for TCR-induced activation in Jurkat cells (10, 12). However, the possibility that nonpalmitoylated LAT fails to reach the PM in the first place is a caveat in this tentative conclusion. Indeed, Tanimura et al. recently reported that transfected nonpalmitoylated LAT was absent from the PM of J. CaM2 cells and was retained, instead, in the Golgi apparatus (15). Therefore, we analyzed the cellular localization of LATwt-GFP and LATC26/29A-GFP in splenocytes and thymocytes from Lat−/− BM chimeric mice. The fluorescence pattern of LATwt-GFP was consistent with PM localization as well as intracellular staining reminiscent of the Golgi apparatus (Fig. 2A). However, cells from LAT-C26/29A-GFP-infected Lat−/− BM chimeras showed only an intracellular staining consistent with the Golgi. These results confirm the earlier report (15) and, moreover, extend it to primary T cells. We also determined the expression level of LATwt-GFP and LATC26/29A-GFP in PBLs from these BM chimeric mice by ICS of fixed cells (Fig. 2B). LATwt-GFP was expressed to a slightly higher degree than LATC26/29A-GFP.

Figure 2.

LAT palmitoylation is required for its PM localization. A, Splenocytes (left panels) and thymocytes (right panels) from LATwt-GFP and LAT-C26/29A-GFP BM chimeric mice were directly analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. B, Histogram of GFP expression in PBL from LATwt-GFP and LAT-C26/29A-GFP BM chimeric mice. C and D, Mouse CD4+ T cells were infected with LATwt-GFP or LAT-C26/29A-GFP (green), stained with anti-CD4 as a PM marker (red; C) or with anti-GM130 as Golgi marker (red; D), and then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. An intensity profile for LAT (green) and CD4 or GM130 (red) along the dashed line was obtained from the merged image. The DAPI profile was removed to increase clarity. Frequency scatter plots display the intensity of LAT pixels on the x-axis and the intensity of CD4 or GM130 pixels on the y-axis. Nuclei of all cells were stained with DAPI (blue). Depicted photos are representative of at least 20 GFP+ cells each. Bar, 10 μm.

To further elucidate the localization of transduced LAT, primary CD4+ T cells from normal B6 mice were retrovirally infected with LATwt-GFP or LAT-C26/29A-GFP in vitro. As markers for the PM and Golgi compartments, we used Abs specific for CD4 (Fig. 2C) or the Golgi marker GM130 (Fig. 2D), respectively. LATwt-GFP colocalized with CD4 in the PM and with GM130 in the Golgi. In contrast, LAT-C26/29A-GFP was absent from the PM, and it was almost exclusively restricted to an intracellular compartment overlapping with the Golgi apparatus. Hence, nonpalmitoylated LAT most likely failed to reach the PM. Line profiles of LATwt-GFP showed usually three major peaks. The two peripheral ones overlapped with CD4, whereas the middle one overlapped with GM130. In contrast, the line profiles of LAT-C26/29A-GFP showed only one major peak that overlapped with GM130, but not with CD4. Scatter plots of LATwt-GFP and CD4 showed a high degree of correlation (Rtotal = 0.82 ± 0.15 (mean ± SD, n = 20)), whereas LAT-C26/29A-GFP and CD4 showed random localization (Rtotal = 0.04 ± 0.11). Additionally, 73.7 ± 19.1% of total LATwt-GFP colocalized with CD4 (% green Int). In contrast, only 5.9 ± 5.2% of total LAT-C26/29A-GFP colocalized with CD4.

Monopalmitoylation of LAT Cys26 is sufficient for PM localization and T cell development

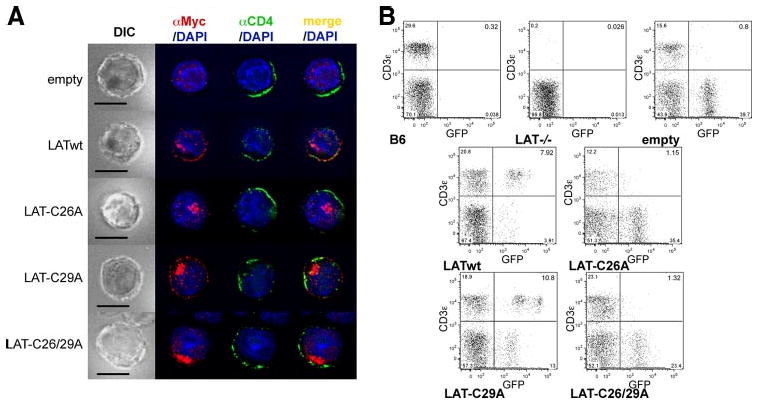

LAT is dually palmitoylated on Cys26 and Cys29 (11), but palmitoylation of LAT Cys26 was found to be more important than palmitoylation of Cys29 for its lipid raft localization (11) and TCR signaling function in LAT-deficient Jurkat cells (12). Therefore, we examined whether the dominant role of Cys26 reflects its greater importance in transporting LAT to the PM. Similar to LATwt, LAT-C29A colocalized with the PM marker CD4 in retrovirally infected mouse CD4+ T cells (Fig. 3A). In contrast, LAT-C26A and the doubly mutated LAT-C26/29A did not display any colocalization with CD4, and only colocalized with the Golgi marker GM130 (data not shown). We additionally determined the localization of these differentially palmitoylated LAT proteins in transfected J.CaM2 and found an identical pattern (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Palmitoylation of LAT Cys26 is sufficient for LAT PM localization and T cell development. A, Mouse CD4+ T cells were infected with empty vector, LATwt, LAT-C26A, LAT-C29A, or LAT-C26/29A, stained with anti-Myc to localize exogenous LAT variants (red), with anti-CD4 (green), and with DAPI (blue), and then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. One representative cell from at least 25 cells analyzed per group is shown. Bar, 10 μm. B, Lat−/− BM cells were infected as in A and then transferred into irradiated B6 mice. After 6 wk blood was analyzed for the presence of T cells. Untreated B6 and Lat−/− mice were used as controls. Diagrams are representative for one of four mice per group from two independent experiments.

Next, we used the BM chimera system described above to determine whether single palmitoylation of LAT at Cys26 would also be sufficient for restoring T cell development. Analysis of peripheral blood cells 6 wk following reconstitution with LAT-GFP-transduced BM cells revealed the presence of CD3+GFP+ T cells in LATwt- and LAT-C29A-transduced, but not in LAT-C26A or LAT-C26/29A-transduced, BM chimeric mice (Fig. 3B). Statistical analysis of eight individual mice per group analyzed in two independent experiments revealed the following percentages of CD3+ cells per GFP+ lymphocytes in the peripheral blood: empty vector, 1.5 ± 0.5% (mean ± SEM); LATwt, 50.5 ± 12.0%; LAT-C26A, 2.3 ± 0.4%; LAT-C29A, 34.6 ± 9.4%; and LAT-C26/29A, 3.6 ± 0.6%. As a control, no GFP+ cells were evident in intact B6 or LAT−/− mice. In conclusion, the ability of LAT mutants to rescue T cell development fully correlated with their PM localization, thus indicating that the Cys26-dependent PM localization of LAT is also critical and sufficient for its obligatory function in T cell development.

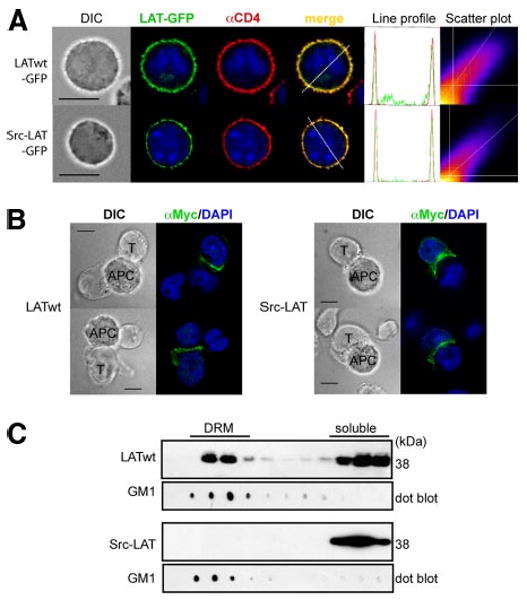

A Src-LAT chimera localizes in the PM and IS, but outside lipid rafts

The above findings suggest that the PM localization of LAT, rather than its lipid raft localization, is required for its proper function. This notion is consistent with the report that a PM-targeted, but non-lipid raft-residing fusion protein consisting of the extracellular and TM domain of the LAT-related adaptor, LAX, and the cytoplasmic domain (lacking Cys26 and Cys29) of LAT restored T cell development and activation in transgenic mice on a Lat−/− background (13). To extend this observation, we next wanted to determine whether a chimeric LAT protein (Src-LAT) expressed as a peripheral (rather than integral) membrane protein is also functional. Therefore, we generated a construct consisting of the membrane-targeting N-terminal 20-aa residues of Src kinase, fused to the intracellular domain (residues 34–233) of LAT, which lacks the two palmitoylation sites but contains all Tyr residues required for its adaptor function (19). Src is a peripheral membrane protein targeted to the PM via its N-terminal myristoylation and the presence of positively charged amino acids. However, in contrast to other Src-family members such as Lck or Fyn, Src is not palmitoylated and therefore is not localized in lipid rafts (20). The Src-LAT chimera was then tested for its ability to restore T cell functions in transfected LAT-deficient Jurkat cells or in the BM chimera system described above.

First, we examined the localization of Src-LAT in retrovirally infected mouse CD4+ T cells. Src-LAT-GFP showed an expression pattern consistent with the PM (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, Src-LAT-GFP colocalized with the PM marker CD4 (Rtotal = 0.60 ± 0.14; % green Int = 54.10 ± 14.30%; n = 20). Similarly, Src-LAT was present in the PM of transfected J.CaM2 cells (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Src-LAT localizes in the PM outside lipid rafts and is enriched in the IS. A, Mouse CD4+ T cells were infected with LATwt-GFP or Src-LAT-GFP (green), stained with anti-CD4 as a PM marker (red) and with DAPI (blue), and then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (left). An intensity profile for LAT (green) and CD4 (red) along the dashed line was obtained from the merged image (right). The DAPI profile was removed to increase clarity. Frequency scatter plots display the intensity of LAT pixels on the x-axis and the intensity of CD4 pixels on the y-axis. Depicted images are representative of at least 20 GFP+ cells each. Bar, 10 μm. B, Transfected J.CaM2 cells (T) were incubated with SEE-pulsed Raji cells (APC) for 20 min. LATwt and Src-LAT were detected by anti-Myc staining. LATwt and Src-LAT enrichment in the IS was observed in >80% of conjugates between J.CaM2 cells and SEE-pulsed Raji cells. The number of conjugates between J.CaM2 cells and unpulsed Raji cells was very low, and enrichment of LATwt or Src-LAT was found in <5% of these conjugates (not shown). Bar, 10 μm. C, Transfected J.CaM2 cells were lysed and subjected to a sucrose gradient fractionation. Fractions were immunoblotted with cholera-toxin B subunit to identify DRM fractions (GM1), and with anti-Myc to detect LATwt and Src-LAT. One representative blot from two independent experiments is shown.

LAT partitions to the IS, which forms in the contact area between T cells and APCs (21). The presence of LAT in the IS is thought to be important for TCR signaling. To determine whether Src-LAT localizes in the IS, J.CaM2 cells were transfected with LATwt or Src-LAT and then stimulated with SEE superantigen-pulsed Raji APCs. Both LATwt (Fig. 4B, left panel) and Src-LAT (Fig. 4B, right panel) were found concentrated in the contact area between the transfected J.CaM2 cells and the APCs, in contrast to their uniform and homogeneous membrane localization in unstimulated cells (Fig. 4A). This result indicates that Src-LAT, despite being expressed as a peripheral membrane protein, is fully capable of localizing in the IS following Ag stimulation.

Lastly, we confirmed that, in contrast to LATwt, which was abundantly present in the DRM fractions of transfected JCaM2 cells, Src-LAT was absent from these fractions and was fully found in the detergent-soluble cell fractions (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained in 293T cells transfected with the same LAT expression vectors (data not shown). Additionally, standard subcellular fractionation revealed that Src-LAT was present in the membrane, but not in the cytosol fraction of transfected J.CaM2 cells (data not shown).

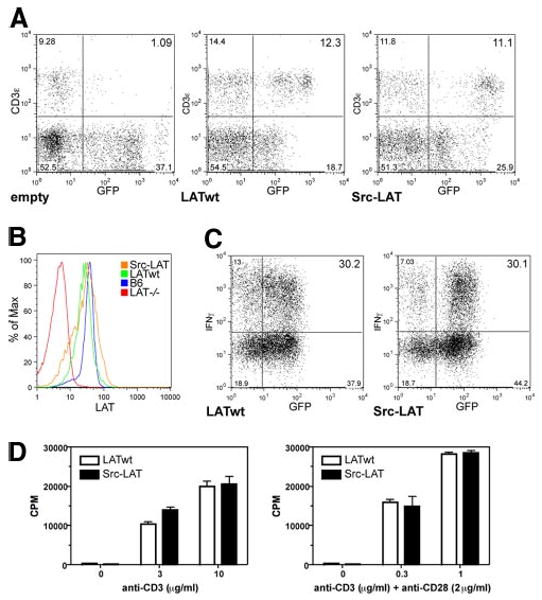

Src-LAT restores T cell development and function of peripheral CD4+ T cells

To analyze the functionality of Src-LAT in the context of primary T cells, we generated intact B6 BM chimeras reconstituted with retrovirally transduced Src-LAT (or LATwt as a positive control) on a Lat−/− background and analyzed the ability of Src-LAT to restore T cell development and peripheral T cell differentiation as well as function. Transduced Src-LAT reconstituted T cell development to the same extent as LATwt, as indicated by the presence of a similar proportion (11–12%) of CD3+GFP+ T cells in the peripheral blood of the chimeric mice (Fig. 5A). The average percentages of CD3+GFP+ cells in the peripheral blood of eight mice per group from two independent experiments were: empty vector, 2.0 ± 0.9%; LATwt, 48.9 ± 7.1%; and Src-LAT, 35.7 ± 10.2%. Similar results were obtained after transfer of LAT-transduced BM cells into irradiated Rag1−/− or Lat−/− recipient mice (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Src-LAT can reconstitute T cell development and is functional in Lat−/− BM chimeric mice. A, Lat−/− BM cells were infected with empty vector, LATwt, or Src-LAT and then transferred into irradiated B6 mice. After 6 wk, blood was analyzed for the presence of T cells. Diagrams are representative for one of four mice per group from two independent experiments. B, Expression of endogenous LAT in CD4+ splenocytes of B6 mice, the background staining for LAT in splenocytes from Lat−/− mice, and the expression of exogenous LATwt and Src-LAT in CD4+GFP+ splenocytes from BM chimeric mice were determined by intracellular staining with anti-LAT and subsequent flow cytometry. C, CD4+ T cells from LATwt and Src-LAT BM chimeric mice were cultured under Th1 conditions, restimulated with anti-CD3ε plus anti-CD28 mAbs, and then IFN-γ was measured by ICS. One representative example of two independent experiments is shown. D, CD4+ T cells from LATwt and Src-LAT BM chimeric mice were stimulated with different concentrations of anti-CD3ε alone (left panel) or in combination with anti-CD28 (right panel). Proliferation was measured after 72 h.

Expression levels of the retrovirally transduced LATwt and Src-LAT proteins detected by ICS were comparable to the endogenous LAT expression level in CD4+ T cells from nontransduced normal B6 mice (Fig. 5B). Therefore, we can rule out the possibility that artificially high expression of Src-LAT would somehow overcome the deficient TCR signaling function, even when it is absent from lipid rafts.

To analyze the functional status of peripheral Src-LAT-expressing T cells from these BM chimeric mice, we isolated GFP+CD4+ T cells from LATwt and Src-LAT BM chimeras, cultured them under Th1 differentiation conditions, and then measured IFN-γ expression following anti-CD3 plus anti-CD28 mAb stimulation by ICS. Th1 cells from Src-LAT-reconstituted BM chimeras displayed a similar percentage (∼30%) of IFN-γ+ cells as did Th1 cells from LATwt-reconstituted mice (Fig. 5C).

As an additional functional test, naive GFP+CD4+ T cells from LATwt-GFP and Src-LAT-GFP BM chimeras were stimulated in vitro with different concentrations of plate-bound anti-CD3ε alone, or in combination with a fixed concentration of anti-CD28 mAb, for 3 days. There was no difference in the proliferative response between GFP+CD4+ T cells from LATwt and Src-LAT chimeric mice (Fig. 5D).

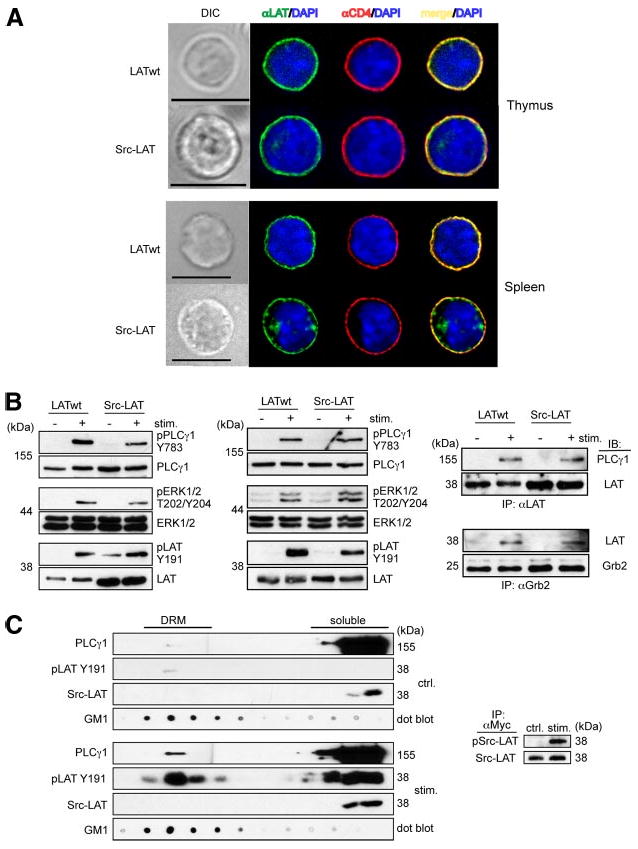

Localization and signaling of Src-LAT in reconstituted BM chimeras

The PM localization of Src-LAT was confirmed in BM chimeric mice by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 6A). Similar to LATwt, Src-LAT colocalized with the PM marker CD4 in thymocytes and spleen from these BM chimeras.

Figure 6.

Src-LAT reconstitutes TCR signaling in Lat−/− BM chimeric mice. A, Thymocytes and splenocytes from Lat−/− BM chimeric mice were stained with anti-LAT (green), anti-CD4 (red), and DAPI (blue) and then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Depicted images are representative of at least 20 GFP+ cells each. Bar, 10 μm. B, Thymocytes (left panel) and splenic CD4+ T cells (middle and right panels) from Lat−/− BM chimeric mice were stimulated for 1 min with anti-CD3 plus anti-CD4 mAbs, or for 2 min with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD28 mAbs, respectively. Cell lysates were directly immunoblotted (left and middle panels) or first immunoprecipitated with anti-LAT (upper right panel) or anti-Grb2 (lower right panel). Representative blots from two independent experiments are shown. C, Src-LAT infected CD4+ T cells from B6 mice were left unstimulated (upper left panels) or stimulated with anti-CD3ε plus anti-CD28 mAbs for 2 min (lower left panels), lysed, and then subjected to sucrose gradient fractionation. Fractions were immunoblotted with cholera-toxin B subunit to identify DRM fractions (GM1), with anti-PLCγ1, with anti-Myc to detect exogenous Src-LAT, and with anti-phospho LAT Y191 (pLAT Y191) to label phosphorylated endogenous LAT (wt) and exogenous Src-LAT (indistinguishable by size). Src-LAT was immunoprecipitated from the soluble fraction with anti-Myc and then blotted with anti-pTyr and anti-LAT Abs (right panel). Representative blots from two independent experiments are shown.

For biochemical analysis of signaling, thymocytes from LATwt- and Src-LAT-reconstituted BM chimeric mice were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3ε and anti-CD4. Stimulated thymocytes from Src-LAT-reconstituted chimeras showed phosphorylation (i.e., activation) of PLCγ1 on Tyr783, ERK1/2 on Thr202/Tyr204, and the cytoplasmic tail of LAT itself on Tyr191, although the phosphorylation of PLCγ1 and ERK1/2 was slightly reduced compared with LATwt-transduced thymocytes (Fig. 6B, left panel). Similar experiments were done with peripheral GFP+CD4+ T cells from these mice. In this case T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3ε plus anti-CD28 mAbs. As in thymocytes, Src-LAT was phosphorylated and capable of fully restoring phosphorylation of PLCγ1 and ERK1/2 (Fig. 6B, middle panel). Additionally, PLCγ1 (Fig. 6B, upper right panel) and Grb2 (Fig. 6B, lower right panel) co-immunoprecipitated with Src-LAT to a similar degree as with LATwt in an activation-dependent manner.

To formally exclude the possibility that Src-LAT expressed in mouse CD4+ T cells translocates to lipid rafts after TCR stimulation, we analyzed the DRM vs soluble fraction localization of retrovirus-transduced Myc-tagged Src-LAT and its phosphorylation status before (Fig. 6C, left upper panels) or after (Fig. 6C, left lower panels) CD3ε and CD28 crosslinking. Src-LAT (detected by anti-Myc immunoblotting) was exclusively present in the soluble fractions, but not in DRM fractions, both before and after TCR stimulation. A very low basal level of phospho-Tyr191 LAT was detected in the DRM (but not soluble) fraction of unstimulated T cells, and this level greatly increased in both fractions as a result of TCR stimulation. Under this SDS-PAGE separation condition, endogenous LAT could not be distinguished from Src-LAT. As an additional control for proper activation of the T cells, we also observed TCR-induced translocation of PLCγ1 to the DRM fractions. To determine whether TCR stimulation induced phosphorylation of the Src-LAT protein, we immunoprecipitated it from the soluble fractions using an anti-Myc mAb and immunoblotted the resulting immunoprecipitates with an anti-pTyr Ab. This analysis revealed that TCR stimulation induced prominent Tyr phosphorylation of Src-LAT (Fig. 6C, right panel), despite the fact that it was undetectable in the DRM fractions.

Discussion

We reported recently that anergic T cells display a relatively selective defect in the palmitoylation of LAT (22). As a result of this impaired palmitoylation, LAT was largely absent from lipid rafts or DRMs and was poorly phosphorylated on Tyr in response to TCR stimulation, resulting in defective recruitment of other signaling proteins such as PLCγ1. However, as described earlier (see Introduction), whether the localization of LAT in membrane lipid rafts is required for its proper function has been a matter of debate, with conflicting results reported over time (11–13). Therefore, as a first step toward resolving the molecular basis of the impaired LAT palmitoylation in anergic T cells, we set out to examine in detail the cellular localization of nonpalmitoylated LAT and determine the relative importance of its raft vs PM localization for its function.

Our findings clearly demonstrate that the palmitoylation of intact LAT is required for its function in T cell development and TCR-induced T cell activation, and they confirm previous studies that reached the same conclusion (10, 12). However, this palmitoylation does not reflect a requirement for lipid raft localization, as has previously been assumed, but, rather, the obligatory role of palmitoylation in targeting LAT from the Golgi apparatus to the PM. Thus, in the absence of palmitoylation, that is, when the palmitoylated cysteine residues of LAT are mutated, LAT was trapped in an intracellular compartment, predominantly in the Golgi apparatus, and was absent from the PM in both reconstituted J.CaM2 cells and peripheral mouse CD4+ T cells. This observation confirms a recent report (15) and, furthermore, extends it, for the first time, to primary T cells. BM chimeric mice expressing nonpalmitoylated LATC26/29A on a Lat−/− background failed to develop peripheral T cells due to a block in thymocyte differentiation at the DN stage, similar to control Lat−/− mice. Additionally, we found that Cys26, but not Cys29, was critical for the PM localization of LAT. Lastly, consistent with the notion that the primary function of LAT palmitoylation (at least on Cys26) is to target it to the PM in a functional form, we found that a chimeric Src-LAT protein, which was localized in the PM, but was absent from lipid rafts, could reconstitute TCR signaling, T cell development, and function in BM chimeric mice. This finding further proves that the lipid raft localization of LAT is dispensable for its function, and that LAT palmitoylation is required primarily for its transport to the PM. Hence, the lipid raft localization of LAT is a secondary consequence of its palmitoylation, which is not required for TCR signaling per se. Although one of the studies demonstrating the importance of LAT palmitoylation for its function (11) claimed that the cysteine-mutated LAT was localized in the membrane, this localization was not rigorously analyzed by co-staining for a PM marker, as done herein. Similar to LAT, other TRAPs such as NTAL/LAB and LIME require palmitoylation for their transport to the PM (23) (data not shown). In contrast, the fourth palmitoylated member of the TRAP family, PAG/Cbp, requires no palmitoylation for PM localization (24) (data not shown).

LAT has a very short extracellular domain of 4 residues, a TM domain of 23 residues, and a long cytoplasmic tail of 206 aa, but interestingly it lacks an intrinsic signal peptide for PM insertion. Therefore, its palmitoylation, particularly on Cys26, would appear to serve an essential role of targeting it from an intracellular compartment, where it is synthesized, to the PM, where it can interact with the TCR signaling machinery. In the cysteine-lacking LAT fusion proteins, that is, LAX-LAT (13), or the Src-LAT protein analyzed herein, intrinsic PM-targeting motifs derived from LAX and Src, respectively, presumably target the cytoplasmic domain of LAT to the PM. Remarkably, NTAL/LAB and LAT are internalized after BCR or TCR stimulation, respectively, whereas PAG/Cbp is not internalized after BCR stimulation (23, 25). These findings highlighting the importance of palmitoylation in targeting TRAPs, including LAT, to the PM are consistent with recent studies that revealed a novel, hitherto unsuspected role for protein palmitoylation, that is, that of regulating various aspects of protein sorting within the cells (2, 26–28).

Our findings raise a question regarding the mechanism through which palmitoylation promotes the transport of LAT from an intracellular compartment to the PM. Palmitoylation of caveolin-1 has been shown to increase its affinity for cholesterol (29), and it is known that cholesterol is transported by vesicular traffic from the endoplasmic reticulum via the Golgi to the PM (30). Hence, one possibility is that LAT uses these cholesterol vesicles as shuttles for its transport to the PM. Another possibility is that the TM domain of LAT, which consists of 23 aa residues, in contrast to the more abundant length of 21 residues found in many other TM proteins, might be too long to optimally match the thickness of the membrane, a phenomenon called hydrophobic mismatch (26). In this case, the palmitoylation of LAT might result in tilting of the TM domain, thereby generating a more favorable conformation in the membrane. Such a scenario is supported by the finding that shortening of the TM domain of LRP6, a palmitoylated subunit of the anthrax toxin receptor complex, from 23 to 19–21 residues rescued its transport from the endoplasmic reticulum to the PM even without being palmitoylated (31).

The finding that Src-LAT restores T cell development and function is similar to the report that a nonpalmitoylated, chimeric LAX-LAT protein also restored T cell development and activation in LAT−/− mice (13). However, in contrast to the LAX-LAT fusion protein, which is an integral TM protein, the Src-LAT protein that we analyzed here is a peripheral membrane protein attached to the inner face of the PM via its Src-derived myristoylation signal and polybasic motif. Hence, this finding extends the report by Zhu et al. by demonstrating, for the first time, that the cytoplasmic tail of LAT is sufficient to restore T cell function even when it is attached to the PM as a peripheral protein (13). The functionality of the two nonpalmitoylated LAT fusion proteins, Src-LAT and LAX-LAT, raises an important question, namely, how do these chimeric LAT proteins signal outside of lipid rafts? Relevant in this regard, single molecule and scanning confocal imaging revealed that LAT, Lck kinase, and the CD2 coreceptor cocluster in discrete PM microdomains that are not maintained by interactions with lipid rafts or actin, and that these microdomains require protein-protein interactions mediated through LAT phosphorylation (32). Based on these findings, it was suggested that diffusional trapping through protein-protein interactions creates microdomains that concentrate or exclude cell surface proteins to facilitate T cell signaling.

Consistent with this idea, recent studies implicated LAT-mediated protein-protein interactions, which are independent of its palmitoylation or lipid raft localization, as being important for its function (21, 25, 33–35). Therefore, these LAT-mediated protein-protein interactions are likely to play an important contributory role in forming LAT-nucleated signaling complexes that cocluster with the TCR when T cells are engaged by APCs. LAT was recently found to colocalize with TCR microclusters that form at the periphery of the IS in Ag-stimulated T cells (36–38), and it would be interesting to determine whether Src-LAT (or LAX-LAT) is also found in these peripheral TCR microclusters and, if so, whether manipulations that disrupt lipid raft integrity or the association of LAT with other signaling proteins impair this colocalization.

A corollary question emerging from our finding that the nonpalmitoylated (and non-raft-residing) Src-LAT protein can restore T cell development and activation concerns the overall importance of lipid rafts for TCR signaling. This is still a controversial question (39). Many studies addressing the importance of lipid rafts in T cell signaling have relied on the use of methyl-β-cyclodextrin to disrupt lipid rafts by depletion of cholesterol (40). However, in addition to disruption of lipid rafts, methyl-β-cyclodextrin inhibits TCR signaling by nonspecific depletion of intracellular Ca2+ stores and PM depolarization (41). Furthermore, alternative methods for cholesterol depletion using cholesterol oxidase or depletion of sphingomyelin with sphingomyelinase led to the conclusion that lipid rafts are not required for TCR signaling (42, 43). On the other hand, conclusions based on the effects of mutating palmitoylated cysteine residues as a way of preventing the lipid raft localization of signaling proteins need to be reexamined given our findings and those by others (34) that, in some cases (and certainly in the case of LAT), palmitoylation is required in the first place for sorting to the PM.

Our finding that Cys26, but not Cys29, was critical for the PM localization of LAT is consistent with, and provides an explanation for, a previous report demonstrating the greater importance of this residue in the lipid raft localization, TCR-induced phosphorylation, and signaling function of LAT (10). Other examples exist where each of two palmitoylation sites in a protein differentially affect protein localization (44, 45), including the finding that palmitoylation of Cys3, but not Cys6, in Fyn kinase was essential for its rapid PM targeting (46). Differential regulation of palmitoylation at distinct sites in a given protein may be explained by the preference of different members of the recently described PAT family for distinct palmitoylation motifs, and could also be affected by the colocalization of a given PAT vis-à-vis its substrate in internal (endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi) and external (PM) cellular membranes (26, 47–49). Hence, it is possible that under physiological conditions, different PATs palmitoylate Cys26 and Cys29 of LAT and/or that Cys26 and Cys29 are palmitoylated at different cellular locations, for example, Cys26 in the Golgi apparatus, and Cys29 in the PM. Ongoing studies aimed at identifying PATs that palmitoylate LAT, and determining their cellular localization vis-à-vis LAT, are likely to be informative.

In summary, our findings reveal a novel role for LAT palmitoylation on Cys26 as a sorting signal essential for its transport from the Golgi apparatus to the PM. These findings have potential implications for other palmitoylated proteins involved in TCR signaling, and they raise the possibility that the function of some of these proteins may also be regulated at the level of PM sorting, rather than by their lipid raft localization per se. Future analysis of how palmitoylation regulates the localization, trafficking, and function of signaling proteins, including the study of palmitoyl transferases that mediate this posttranslational protein modification, are likely to shed new light on the molecular basis for T cell activation and establish a new immunoregulatory paradigm mediated by reversible protein palmitoylation in cells of the immune system.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Keitaro Hayashi for help with vector design, and Dr. Yun-Cai Liu for advice. This is manuscript no. 1069 from the La Jolla Institute for Allergy & Immunology.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI081078 and by institutional funds (to A.A.), and by a Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Special Fellowship (to M.H.).

Abbreviations used in this paper: BM, bone marrow; B6 (mice), C57BL/6 mice; DAPI, 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DN, double negative; DRM, detergent-resistant membrane; ICS, intracellular staining; IS, immunological synapse; LAT, linker for activation of T cells; LAX, linker for activation of X cells; PAT, protein acyl transferase; PM, plasma membrane; SEE, Staphylococcus enterotoxin E; TM, transmembrane; TRAP, transmembrane adaptor protein; wt, wild type; Int, intensity.

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Linder ME, Deschenes RJ. New insights into the mechanisms of protein palmitoylation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:4311–4320. doi: 10.1021/bi034159a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resh MD. Trafficking and signaling by fatty-acylated and prenylated proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nchembio834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fukata M, Fukata Y, Adesnik H, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Identification of PSD-95 palmitoylating enzymes. Neuron. 2004;44:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Resh MD. Palmitoylation of ligands, receptors, and intracellular signaling molecules. Sci STKE. 2006;2006:re14. doi: 10.1126/stke.3592006re14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webb Y, Hermida-Matsumoto L, Resh MD. Inhibition of protein palmitoylation, raft localization, and T cell signaling by 2-bromopalmitate and polyunsaturated fatty acids. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:261–270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horejsi V, Zhang W, Schraven B. Transmembrane adaptor proteins: organizers of immunoreceptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:603–616. doi: 10.1038/nri1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang W, Sloan-Lancaster J, Kitchen J, Trible RP, Samelson LE. LAT: the ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell. 1998;92:83–92. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80901-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finco TS, Kadlecek T, Zhang W, Samelson LE, Weiss A. LAT is required for TCR-mediated activation of PLCγ1 and the Ras pathway. Immunity. 1998;9:617–626. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang W, Sommers CL, Burshtyn DN, Stebbins CC, DeJarnette JB, Trible RP, Grinberg A, Tsay HC, Jacobs HM, Kessler CM, et al. Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity. 1999;10:323–332. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang W, Irvin BJ, Trible RP, Abraham RT, Samelson LE. Functional analysis of LAT in TCR-mediated signaling pathways using a LAT-deficient Jurkat cell line. Int Immunol. 1999;11:943–950. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.6.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang W, Trible RP, Samelson LE. LAT palmitoylation: its essential role in membrane microdomain targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation during T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;9:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80606-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin J, Weiss A, Finco TS. Localization of LAT in glycolipid-enriched microdomains is required for T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28861–28864. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.41.28861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu M, Shen S, Liu Y, Granillo O, Zhang W. Cutting edge: localization of linker for activation of T cells to lipid rafts is not essential in T cell activation and development. J Immunol. 2005;174:31–35. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holst J, Szymczak-Workman AL, Vignali KM, Burton AR, Workman CJ, Vignali DA. Generation of T-cell receptor retrogenic mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:406–417. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tanimura N, Saitoh S, Kawano S, Kosugi A, Miyake K. Palmitoylation of LAT contributes to its subcellular localization and stability. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;341:1177–1183. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morita S, Kojima T, Kitamura T. Plat-E: an efficient and stable system for transient packaging of retroviruses. Gene Ther. 2000;7:1063–1066. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Su YW, Jumaa H. LAT links the pre-BCR to calcium signaling. Immunity. 2003;19:295–305. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00202-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oya K, Wang J, Watanabe Y, Koga R, Watanabe T. Appearance of the LAT protein at an early stage of B-cell development and its possible role. Immunology. 2003;109:351–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu M, Janssen E, Zhang W. Minimal requirement of tyrosine residues of linker for activation of T cells in TCR signaling and thymocyte development. J Immunol. 2003;170:325–333. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.1.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shenoy-Scaria AM, Dietzen DJ, Kwong J, Link DC, Lublin DM. Cysteine-3 of Src family protein tyrosine kinase determines palmitoylation and localization in caveolae. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:353–363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harder T, Kuhn M. Selective accumulation of raft-associated membrane protein LAT in T cell receptor signaling assemblies. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:199–208. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hundt M, Tabata H, Jeon MS, Hayashi K, Tanaka Y, Krishna R, de Giorgio L, Liu YC, Fukata M, Altman A. Impaired activation and localization of LAT in anergic T cells as a consequence of a selective palmitoylation defect. Immunity. 2006;24:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mutch CM, Sanyal R, Unruh TL, Grigoriou L, Zhu M, Zhang W, Deans JP. Activation-induced endocytosis of the raft-associated transmembrane adaptor protein LAB/NTAL in B lymphocytes: evidence for a role in internalization of the B cell receptor. Int Immunol. 2007;19:19–30. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Posevitz-Fejfar A, Smida M, Kliche S, Hartig R, Schraven B, Lindquist JA. A displaced PAG enhances proximal signaling and SDF-1-induced T cell migration. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:250–259. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonello G, Blanchard N, Montoya MC, Aguado E, Langlet C, He HT, Nunez-Cruz S, Malissen M, Sanchez-Madrid F, Olive D, et al. Dynamic recruitment of the adaptor protein LAT: LAT exists in two distinct intracellular pools and controls its own recruitment. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:1009–1016. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greaves J, Chamberlain LH. Palmitoylation-dependent protein sorting. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:249–254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petaja-Repo UE, Hogue M, Leskela TT, Markkanen PM, Tuusa JT, Bouvier M. Distinct subcellular localization for constitutive and agonist-modulated palmitoylation of the human δ opioid receptor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15780–15789. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602267200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam KK, Davey M, Sun B, Roth AF, Davis NG, Conibear E. Palmitoylation by the DHHC protein Pfa4 regulates the ER exit of Chs3. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:19–25. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200602049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uittenbogaard A, Smart EJ. Palmitoylation of caveolin-1 is required for cholesterol binding, chaperone complex formation, and rapid transport of cholesterol to caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25595–25599. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003401200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heino S, Lusa S, Somerharju P, Ehnholm C, Olkkonen VM, Ikonen E. Dissecting the role of the Golgi complex and lipid rafts in biosynthetic transport of cholesterol to the cell surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8375–8380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140218797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abrami L, Kunz B, Iacovache I, van der Goot FG. Palmitoylation and ubiquitination regulate exit of the Wnt signaling protein LRP6 from the endoplasmic reticulum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:5384–5389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710389105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Douglass AD, Vale RD. Single-molecule microscopy reveals plasma membrane microdomains created by protein-protein networks that exclude or trap signaling molecules in T cells. Cell. 2005;121:937–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shogomori H, Hammond AT, Ostermeyer-Fay AG, Barr DJ, Feigenson GW, London E, Brown DA. Palmitoylation and intracellular domain interactions both contribute to raft targeting of linker for activation of T cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18931–18942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500247200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanimura N, Nagafuku M, Minaki Y, Umeda Y, Hayashi F, Sakakura J, Kato A, Liddicoat DR, Ogata M, Hamaoka T, Kosugi A. Dynamic changes in the mobility of LAT in aggregated lipid rafts upon T cell activation. J Cell Biol. 2003;160:125–135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200207096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houtman JC, Yamaguchi H, Barda-Saad M, Braiman A, Bowden B, Appella E, Schuck P, Samelson LE. Oligomerization of signaling complexes by the multipoint binding of GRB2 to both LAT and SOS1. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:798–805. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunnell SC, Hong DI, Kardon JR, Yamazaki T, McGlade CJ, Barr VA, Samelson LE. T cell receptor ligation induces the formation of dynamically regulated signaling assemblies. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:1263–1275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Campi G, Varma R, Dustin ML. Actin and agonist MHC-peptide complex-dependent T cell receptor microclusters as scaffolds for signaling. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1031–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito T, Yokosuka T. Immunological synapse and microclusters: the site for recognition and activation of T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw AS. Lipid rafts: now you see them, now you don't. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:1139–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xavier R, Brennan T, Li Q, McCormack C, Seed B. Membrane compartmentation is required for efficient T cell activation. Immunity. 1998;8:723–732. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80577-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pizzo P, Giurisato E, Tassi M, Benedetti A, Pozzan T, Viola A. Lipid rafts and T cell receptor signaling: a critical re-evaluation. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3082–3091. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200211)32:11<3082::AID-IMMU3082>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rouquette-Jazdanian AK, Pelassy C, Breittmayer JP, Aussel C. Revaluation of the role of cholesterol in stabilizing rafts implicated in T cell receptor signaling. Cell Signal. 2006;18:105–122. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rouquette-Jazdanian AK, Pelassy C, Breittmayer JP, Aussel C. Full CD3/TCR activation through cholesterol-depleted lipid rafts. Cell Signal. 2007;19:1404–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Roy S, Plowman S, Rotblat B, Prior IA, Muncke C, Grainger S, Parton RG, Henis YI, Kloog Y, Hancock JF. Individual palmitoyl residues serve distinct roles in H-ras trafficking, microlocalization, and signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6722–6733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.15.6722-6733.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayashi T, Rumbaugh G, Huganir RL. Differential regulation of AMPA receptor subunit trafficking by palmitoylation of two distinct sites. Neuron. 2005;47:709–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van't Hof W, Resh MD. Rapid plasma membrane anchoring of newly synthesized p59fyn: selective requirement for NH2-terminal myristoylation and palmitoylation at cysteine-3. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:1023–1035. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.5.1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huang K, Yanai A, Kang R, Arstikaitis P, Singaraja RR, Metzler M, Mullard A, Haigh B, Gauthier-Campbell C, Gutekunst CA, et al. Huntingtin-interacting protein HIP14 is a palmitoyl transferase involved in palmitoylation and trafficking of multiple neuronal proteins. Neuron. 2004;44:977–986. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keller CA, Yuan X, Panzanelli P, Martin ML, Alldred M, Sassoe-Pognetto M, Luscher B. The γ 2 subunit of GABAA receptors is a substrate for palmitoylation by GODZ. J Neurosci. 2004;24:5881–5891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1037-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swarthout JT, Lobo S, Farh L, Croke MR, Greentree WK, Deschenes RJ, Linder ME. DHHC9 and GCP16 constitute a human protein fatty acyltransferase with specificity for H- and N-Ras. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:31141–31148. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]