Abstract

Hypertension is a multi-factorial disorder thought to result from both genetic and environmental factors. Epidemiological studies suggest that cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension may be programmed in-utero. Experimental studies demonstrate that developmental programming occurs in response to a nutritional insult during fetal life and leads to slow fetal growth and permanent structural and pathophysiological changes that result in the development of hypertension and cardiovascular disease. A reduction in nephron number, hyperfiltration and increased susceptibility to renal injury, activation of the sympathetic and renin angiotensin systems, in addition to, increases in oxidative stress, are potential mediators of post-natal hypertension programmed in response to developmental insult. However, the quantitative importance and integration of these mechanistic pathways has not been clearly elucidated. Additionally, animal models of developmental programming exhibit sex differences with severity of the fetal insult critical to the phenotypic outcome. Recent studies suggest that sex hormones may play a critical role via modulation of the normal regulatory systems involved in the long-term control of arterial pressure. Investigation into sex differences in the developmental programming of hypertension may provide critical insight into the mechanisms linking sex hormones and factors important in blood pressure regulation. Understanding the complexity of the developmental programming of adult disease may lead to preventive measures and early detection of cardiovascular risk.

Keywords: intrauterine growth restriction, sex hormones, nephron number, angiotensin, renal nerves, oxidative stress

INTRODUCTION

Low birth weight (LBW), defined as a birth weight of 2.5 kg or less at term, is a major health issue within the United States today. The risk for LBW is greater within the black population than the white with a greater percentage of LBW occurring within the southern United States relative to other parts of the country 1. Babies born small for gestational age not only have a greater risk for survival at birth 2, 3, but based on numerous epidemiological studies, face long-term consequences such as increased risk for development of hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other health problems 4-6. Barker first proposed that an adverse environmental stimulus experienced during a critical period of fetal development leads to slow fetal growth and permanent structural and physiological changes in the fetus predisposing it to increased risk for development of hypertension and cardiovascular disease 7. Investigators utilizing animal models to induce an adverse fetal environment and mimic the human condition of slow fetal growth are providing convincing evidence to support the concept of developmental programming of adult disease 8-17. Although there is compelling epidemiological and experimental data which suggest that cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension may be programmed in utero, the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms remain unclear. Investigators utilize unique animal models of nutritional manipulation to induce slow fetal growth in order to examine the mechanisms linking birth weight and chronic adult disease such as hypertension. In this review we will discuss alterations in potential mechanistic pathways that evolve in response to fetal insult and lead to the developmental programming of hypertension highlighting insight provided by animal models of nutritional manipulation.

Animal models of nutritional manipulation during fetal life

Nutritional restriction is one of the most common experimental methods of fetal insult utilized for investigation into the mechanisms of programmed hypertension, and was one of the first to demonstrate that exposure to an adverse environment in utero leads to marked structural and physiological alterations 17. Importantly, this method of fetal insult was also one of the first to demonstrate that timing of the insult is critical to the programming response with a reduction in nephron number observed when the nutritional insult coincides with the nephrogenic period 8, 13, 18-21. Observations linking nutritional restriction during gestation with elevated blood pressure in offspring have been controversial 21-24. In the rat variations in dietary nutrient and protein balance are reported to contribute to differing blood pressure responses in offspring 22 with post-natal influences such as excessive weight gain exacerbating the effect 25. In humans, childhood growth is also a strong determinant of adult blood pressure demonstrating the importance of the post-natal environment on adult disease 26. In the sheep model of nutrient restriction birth weight rather than maternal diet may play a more critical role in the blood pressure response 23 with maternal body composition at the time of conception also critical to cardiovascular outcome 21. Animal models of reduced uteroplacental perfusion during late gestation also lead to an environment of undernutrition and hypertension in the intrauterine growth restricted (IUGR) offspring 10, 11. Contention exists in regards to the reproducibility of these models 27. However, consistent observations of IUGR are reported by numerous investigators 10-12, 28, 29; moreover, similar phenotypic outcomes such as a reduction in nephron number is observed in response to placental insufficiency, an observation that is not species specific 29-32. Overnutrition as a nutritional insult during fetal life also programs metabolic and cardiovascular dysfunction 33-35; implications critical due to the increased prevalence of obesity 36.

Importantly, these models of nutritional manipulation demonstrate characteristics reflective of the human condition of LBW including marked increases in blood pressure 10-15, 17, 19, 35, 37, 38 and reduced nephron number 13, 15, 18, 28, 29, 39. In humans, nephron number is directly correlated with birth weight and inversely correlated with blood pressure 40. Thus, models of nutritional insult, whether induced by direct manipulation of the gestational diet or through a reduction in uteroplacental perfusion, serve as relevant pathophysiological models for investigation into the mechanisms linking birth weight and blood pressure and will provide the basis for the discussion of potential mechanistic pathways presented in this review.

Mechanisms of developmental programming of hypertension

Hormones

Hormones are known to play a critical role in the proper development and growth of fetal tissues 41 and it is well documented that alterations in the intrauterine hormonal environment can lead to long-term effects on fetal outcome and cardiovascular health 42-46. In experimental studies, inappropriate exposure to testosterone during gestation results in IUGR44, impaired insulin sensitivity45, and cardiovascular dysfunction 46 demonstrating a critical role for sex hormones in the developmental programming of adult cardiovascular disease.

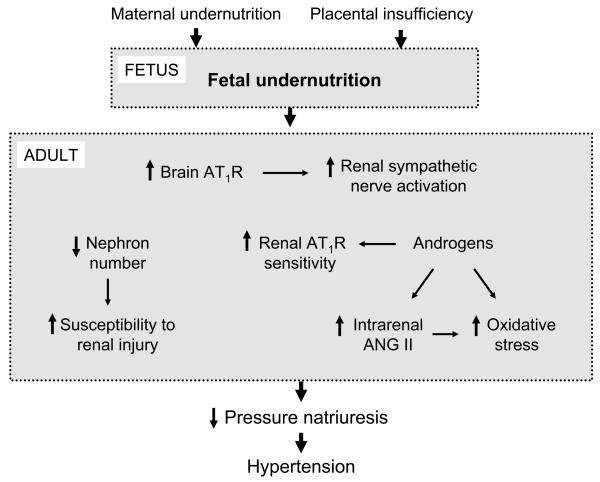

Models of developmental programming exhibit sex differences with severity of the fetal insult critical to the adult phenotypic outcome 18, 47. Whereas, severe protein restriction during gestation in the rat leads to hypertension and changes in renal structure in both male and female offspring15, 18, moderate protein restriction during gestation in the rat leads to marked increases in blood pressure and a reduction in nephron number in male, but not female offspring 15, 18, 47. Therefore, female offspring appear to be protected from an unfavorable phenotypic outcome in response to a moderate under-nutritional insult in utero. However, in models of programming induced by maternal diet-induced obesity, the prevalence for hypertension is greater 35 or present only 38 in female offspring indicating that sex differences in sensitivity to nutritional manipulation is insult specific. Sex differences in adult blood pressure are not observed in models of undernutrition programmed by placental insufficiency in the rat when assessed indirectly by tail cuff in conscious, restrained animals 11, 48. Conversely, sex differences in adult blood pressure are observed when measured directly by telemetry 49, 50; blood pressure after puberty is stabilized to normotensive levels in female IUGR, yet is further increased in male IUGR 49, 50. Castration abolishes hypertension in male IUGR 49; ovariectomy induces hypertension in female IUGR rats, an effect reverted by hormonal replacement therapy 50. Thus, sex differences in the blood pressure response to placental insufficiency in IUGR offspring indicate a potential role for sex hormones in mediating sex differences in the post-natal blood pressure response to fetal insult (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Potential mechanisms for the developmental programming of hypertension in response to nutritional manipulation during fetal development.

Sexual dimorphism is observed in human essential hypertension and in experimental models of hypertension 51-54 with a role for sex hormone involvement strongly indicated. Hypertension is less prevalent in pre-menopausal women as compared to age-matched men. However, after menopause the risk of hypertension increases with age 51, 52 suggesting that while the ovaries are functional women have a lower risk for hypertension and cardiovascular disease than men. Experimental studies suggest sex hormones play a mechanistic role in blood pressure control. Ovariectomy leads to hypertension in female rats normotensive to their male counterparts in some experimental models of hypertension 53, 54 suggesting an important role for estradiol in blood pressure regulation. Androgens exacerbate hypertension in the male spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR)55; castration reduces blood pressure in male SHR 56 thus, indicating a role for androgens. Thus, sex hormones appear to contribute to sex differences in adult blood pressure regulation. Whether sex hormones are altered in LBW individuals is controversial 57-60. Moreover, few investigators have reported whether adult sex hormones are altered in response to fetal insult 61-66, nor have they examined the direct effect of sex hormones on post-natal hypertension in experimental models of developmental programming. Thus, the exact mechanism(s) by which sex hormones contribute to the developmental programming of blood pressure regulation has not been clearly elucidated, but may involve modulation of systems critical to the long term control of blood pressure regulation.

The renin angiotensin system

The renin angiotensin system (RAS) is a major regulator of blood pressure control and volume homeostasis 67. Numerous studies indicate that the RAS plays an important role in the etiology of hypertension programmed by in utero insult 15, 49, 50, 68-72 (Figure 1). A critical role for the central RAS is indicated in hypertension programmed in response to maternal undernutrition in the rat with marked increases in angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) expression observed in areas of the brain critical to cardiovascular regulation 73 (Figure 2). In the kidneys temporal alterations in the RAS occur in response to fetal insult. A reduction in intrarenal renin and angiotensin II (ANG II) is observed at birth in response to maternal protein restriction in the rat 15 followed by post-natal up-regulation of the renal AT1R70, 72. In addition, inappropriate activation of the peripheral RAS, demonstrated by a marked increase in plasma renin activity (PRA), occurs after development of hypertension 68, 69. Importantly, hypertension is abolished by systemic blockade of the RAS 68, 69, 71 indicating that the RAS contributes to hypertension programmed in response to maternal nutrient restriction. In a model of undernutrition induced by placental insufficiency temporal alterations in the renal RAS are also observed with renal angiotensinogen and renin mRNA expression suppressed at birth, but markedly elevated in adulthood 74. Unlike models of maternal nutrient restriction, renal AT1R and ANG II expression as well as inappropriate activation of the peripheral RAS are not observed 49, 50, 74; yet, the importance of the RAS is indicated as hypertension is abolished by RAS blockade 49. Although the contribution of the RAS to the development of hypertension is not clearly defined, it may involve an increased responsiveness to ANG II. Androgens can augment renal vascular responses to ANG II 75. Elevated levels of testosterone are observed in male IUGR programmed in response to placental insufficiency49. Therefore, elevated levels of adult testosterone may be one mechanism by which sensitivity to ANG II is increased, and may also contribute to the enhanced intrarenal renin and angiotensinogen mRNA expression observed in adult male IUGR 76.

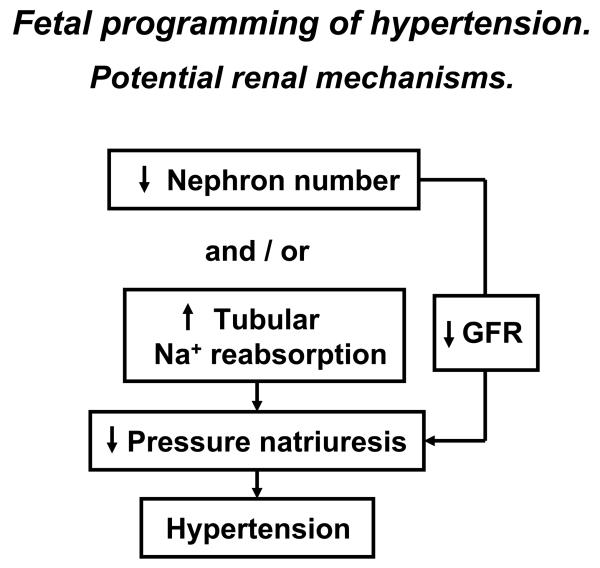

Figure 2.

Potential renal mechanisms whereby developmental programming in response to in utero insult leads to development of hypertension.

Modulation of the RAS by estradiol may also contribute to sex differences in hypertension programmed by fetal insult. Estradiol is reported to downregulate tissue ACE 77 and AT1R mRNA expression 78 suggesting estradiol may reduce ANG II, a potent vasoconstrictor peptide critical for blood pressure regulation 67, 79. Estradiol may also alter the ACE2-dependent pathway 80, which generates ANG (1-7), a negative regulator of the vasoconstrictor effects of ANG II 79. Modulation of the RAS by estradiol may be one mechanism by which sex hormones play a protective role against an increase in blood pressure in adult female IUGR offspring in a model of undernutrition induced by placental insufficiency. Hypertension is induced by ovariectomy in female IUGR, but not female control offspring 50. ACE inhibition abolishes ovariectomy-induced hypertension 50 suggesting a critical role for the RAS. Normotensive adult female IUGR offspring exhibit a significant elevation in renal ACE2 mRNA expression that is decreased by ovariectomy with no effect observed in adult female control 50. Thus, loss of estradiol may decrease the vasodilator effect provided by the ACE2 pathway leading to an increase in blood pressure in adult female IUGR following ovariectomy. Therefore, permanent alterations in the RAS occur in response to fetal insult and contribute to the development of hypertension; modulation of the RAS by sex hormones is one mechanism that may contribute to sex differences in programmed hypertension (Figure 1).

The renal nerves

Many known regulatory mechanisms control sodium balance and alterations in sympathetic activity have sustained effects to reduce pressure natriuresis and result in long-term changes in arterial pressure 81, 82. However, whether sympathetic function contributes to hypertension in LBW individuals is controversial 83-86. Circulating levels of catecholamines, neurotransmitters which serve as an indirect marker of sympathetic nerve outflow, are increased in response to fetal undernutrition in models of developmental programming induced by both gestational protein restriction 87 and also placental insufficiency in the rat 88 and sheep 89. The importance of the renal nerves in the etiology of hypertension programmed by in utero insult was recently demonstrated whereby renal denervation normalized arterial pressure in adult male IUGR offspring in a model of placental insufficiency with no significant effect on blood pressure in adult control offspring 90. Therefore, these findings indicate the renal nerves play an important role in the etiology of hypertension programmed by fetal undernutrition induced by placental insufficiency (Figure 1). Increased sympathetic outflow including sustained increases in renal sympathetic nerve activity can also occur as a result of the actions of ANG II in regions of the brain critical for cardiovascular regulation 91. Thus, central activation of the RAS leading to an increase in RSNA may induce altered renal nerve development in IUGR offspring resulting in hypertension.

Oxidative stress

A decrease in bioavailability of antioxidants leading to an increase in oxidative stress is indicated to play an important role in essential and experimental hypertension 92, 93. Oxidative stress is increased in LBW children 94 suggesting that alterations in oxidant status may contribute to hypertension programmed in response to fetal insult. In experimental models of in utero exposure to undernutrition, hypertension is abolished by administration of the superoxide dismutase mimetic (SOD), tempol 95, or the lipid peroxidation inhibitor, lazaroid 96 implicating an important role for oxidative stress (Figure 1). ANG II stimulates oxidative stress through its AT1R 97. Thus, up-regulation of renal AT1R and inappropriate activation of the RAS may serve as a stimulus for increased oxidative stress in the developmental programming of hypertension.

Nephron number

A reduction in nephron number is a phenotypic outcome commonly observed in the fetal response to gestational insult in experimental models of undernutrition induced by maternal nutrient restriction 8, 14, 15, 20, 21, 98 and placental insufficiency 29-32. A reduction in nephron number leading to a reduction in renal excretory function is suggested to serve as a mechanism in the developmental programming of hypertension. Whether a reduced nephron complement could lead to hypertension was demonstrated in a study whereby removal of one kidney during the nephrogenic period in the rat led to adult hypertension 99. However, recent findings indicate that a reduction in nephron number is not always critical to the developmental programming of hypertension. A maternal diet rich in fat does not alter nephron number in offspring 100. Furthermore, an increase in glomerular volume is often observed in conjunction with reduced nephron number 18. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is not decreased in a rat models of maternal protein restriction 15 or placental insufficiency 10. Thus, compensatory hyperfiltration may occur in response to fewer nephrons at birth resulting in preservation of GFR 10, 15, 98 suggesting that factors other than a reduced nephron complement contribute to the etiology of hypertension programmed by in utero insult. Numerous factors including intrarenal sodium transport defects and/or abnormalities in the extrarenal control systems that regulate kidney function can mediate a reduction in renal sodium excretory function observed in hypertension 101. Thus, a sodium retaining defect not mediated by alterations in the filtered load of sodium may be the main contributor to a reduction in pressure natriuresis and hypertension programmed in response to adverse developmental influences (Figure 2). Whether a reduction in nephron number leading to a decrease in GFR contributes to hypertension programmed in response to fetal insult is unclear. Nevertheless, a reduction in nephron complement may diminish resistance to renal damage in adult life leading to an increased susceptibility to renal disease.

Susceptibility to renal disease

Progression of renal injury and disease is closely linked to hypertension. It is well established that the kidney exhibits increased vulnerability to fetal insult as evidenced by the association of reduced nephron number with IUGR in animal models of fetal nutrient manipulation 8, 14, 15, 20, 21, 29-32, 98 . However, recent studies indicate that susceptibility to renal disease is greater in LBW individuals 102, 103 with implications for a gender bias and a protective role for estradiol in women 104. Hypertension associated with an increase in urinary albuminuria 105, glomerulosclerosis, and histological determinants of renal damage 106, 107 is observed in offspring of nutrient restricted dams. Hypertension, proteinuria, and glomerulosclerosis are reduced by long-term post-natal Larginine supplementation; however, evidence of renal damage persists 106. Therefore, these studies indicate that increased susceptibility to renal damage is not just the result of hypertension, but may have an origin in fetal life. Furthermore, a reduction in nephron number at birth in conjunction with an increase in glomerular size and compensatory hyperfiltration may contribute to an increased susceptibility to renal injury, and enhance the later development of hypertension in LBW individuals (Figure 1).

Perspective

Insight provided by animal models of nutritional manipulation during fetal life suggests that slow fetal growth leads to alterations in the normal regulatory systems involved in the long-term control of blood pressure regulation. The pathogenesis of hypertension programmed by in utero insult is multifactorial and may involve intrinsic intrarenal defects or alterations in extrarenal regulatory systems critical to renal sodium excretory function. Moreover, a role for sex steroids is also demonstrated. Understanding the complexity of the fetal programming of adult disease may lead to preventive measures and early detection of cardiovascular risk in low birth weight individuals.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF FUNDING

Dr. Alexander is supported by NIH grants HL074927 and HL51971.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Sutton PD, Ventura SJ, Menacker F, Kirmeyer S. Births: final data for 2004. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2006;55:1–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bernstein IGS, Reed KL. Intrauterine growth restriction. Churchil Livingstone; Philadelphia: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baschat AA, Hecher K. Fetal growth restriction due to placental disease. Semin Perinatol. 2004;28:67–80. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2003.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huxley RR, Shiell AW, Law CM. The role of size at birth and postnatal catch-up growth in determining systolic blood pressure: a systematic review of the literature. J Hypertens. 2000;18:815–831. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syddall HE, Sayer AA, Simmonds SJ, Osmond C, Cox V, Dennison EM, Barker DJ, Cooper C. Birth weight, infant weight gain, and cause-specific mortality: the Hertfordshire Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;161:1074–1080. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newsome CA, Shiell AW, Fall CH, Phillips DI, Shier R, Law CM. Is birth weight related to later glucose and insulin metabolism?--A systematic review. Diabet Med. 2003;20:339–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.00871.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker D. Mother, babies, and disease in later life. BMJ Publishing Group; London: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Symonds ME, Stephenson T, Gardner DS, Budge H. Long-term effects of nutritional programming of the embryo and fetus: mechanisms and critical windows. Reprod Fertil Dev. 2007;19:53–63. doi: 10.1071/rd06130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodic M, Abouantoun T, O'Connor A, Wintour EM, Moritz KM. Programming effects of short prenatal exposure to dexamethasone in sheep. Hypertension. 2002;40:729–734. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000036455.62159.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alexander BT. Placental insufficiency leads to development of hypertension in growth-restricted offspring. Hypertension. 2003;41:457–462. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000053448.95913.3D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baserga M, Hale MA, Wang ZM, Yu X, Callaway CW, McKnight RA, Lane RH. Uteroplacental insufficiency alters nephrogenesis and downregulates cyclooxygenase-2 expression in a model of IUGR with adult-onset hypertension. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1943–1955. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00558.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schreuder MF, van Wijk JA, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Intrauterine growth restriction increases blood pressure and central pulse pressure measured with telemetry in aging rats. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1337–1343. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000234114.33025.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet impairs nephrogenesis and promotes hypertension in the rat. Life Sci. 1999;64:965–974. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vehaskari VM, Aviles DH, Manning J. Prenatal programming of adult hypertension in the rat. Kidney Int. 2001;59:238–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Nyengaard JR, Rasch R. Maternal protein restriction suppresses the newborn renin-angiotensin system and programs adult hypertension in rats. Pediatr Res. 2001;49:460–467. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200104000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guron G. Renal haemodynamics and function in weanling rats treated with enalapril from birth. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:865–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2010.04278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langley-Evans SC, Phillips GJ, Jackson AA. In utero exposure to maternal low protein diets induces hypertension in weanling rats, independently of maternal blood pressure changes. Clin Nutr. 1994;13:319–324. doi: 10.1016/0261-5614(94)90056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woods LL, Weeks DA, Rasch R. Programming of adult blood pressure by maternal protein restriction: role of nephrogenesis. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1339–1348. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Sherman RC, Jackson AA. Weanling rats exposed to maternal low-protein diets during discrete periods of gestation exhibit differing severity of hypertension. Clin Sci (Lond) 1996;91:607–615. doi: 10.1042/cs0910607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brennan KA, Olson DM, Symonds ME. Maternal nutrient restriction alters renal development and blood pressure regulation of the offspring. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006;65:116–124. doi: 10.1079/pns2005484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gopalakrishnan GS, Gardner DS, Dandrea J, Langley-Evans SC, Pearce S, Kurlak LO, Walker RM, Seetho IW, Keisler DH, Ramsay MM, Stephenson T, Symonds ME. Influence of maternal pre-pregnancy body composition and diet during early-mid pregnancy on cardiovascular function and nephron number in juvenile sheep. Br J Nutr. 2005;94:938–947. doi: 10.1079/bjn20051559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langley-Evans SC. Critical differences between two low protein diet protocols in the programming of hypertension in the rat. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000;51:11–17. doi: 10.1080/096374800100859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oliver MH, Breier BH, Gluckman PD, Harding JE. Birth weight rather than maternal nutrition influences glucose tolerance, blood pressure, and IGF-I levels in sheep. Pediatr Res. 2002;52:516–524. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200210000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gopalakrishnan GS, Gardner DS, Rhind SM, Rae MT, Kyle CE, Brooks AN, Walker RM, Ramsay MM, Keisler DH, Stephenson T, Symonds ME. Programming of adult cardiovascular function after early maternal undernutrition in sheep. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2004;287:R12–20. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00687.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petry CJ, Ozanne SE, Wang CL, Hales CN. Early protein restriction and obesity independently induce hypertension in 1-year-old rats. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997;93:147–152. doi: 10.1042/cs0930147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Falkner B, Hulman S, Kushner H. Birth weight versus childhood growth as determinants of adult blood pressure. Hypertension. 1998;31:145–150. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neitzke U, Harder T, Schellong K, Melchior K, Ziska T, Rodekamp E, Dudenhausen JW, Plagemann A. Intrauterine growth restriction in a rodent model and developmental programming of the metabolic syndrome: A Critical Appraisal of the Experimental Evidence. Placenta. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.11.014. [Epub ahead of print] PMID 18207235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanders MW, Fazzi GE, Janssen GM, de Leeuw PW, Blanco CE, De Mey JG. Reduced uteroplacental blood flow alters renal arterial reactivity and glomerular properties in the rat offspring. Hypertension. 2004;43:1283–1289. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000127787.85259.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merlet-Benichou C, Gilbert T, Muffat-Joly M, Lelievre-Pegorier M, Leroy B. Intrauterine growth retardation leads to a permanent nephron deficit in the rat. Pediatr Nephrol. 1994;8:175–180. doi: 10.1007/BF00865473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bassan H, Trejo LL, Kariv N, Bassan M, Berger E, Fattal A, Gozes I, Harel S. Experimental intrauterine growth retardation alters renal development. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;15:192–195. doi: 10.1007/s004670000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Briscoe TA, Rehn AE, Dieni S, Duncan JR, Wlodek ME, Owens JA, Rees SM. Cardiovascular and renal disease in the adolescent guinea pig after chronic placental insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:847–855. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zohdi V, Moritz KM, Bubb KJ, Cock ML, Wreford N, Harding R, Black MJ. Nephrogenesis and the renal renin-angiotensin system in fetal sheep: effects of intrauterine growth restriction during late gestation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293:R1267–1273. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00119.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khan IY, Dekou V, Douglas G, Jensen R, Hanson MA, Poston L, Taylor PD. A high-fat diet during rat pregnancy or suckling induces cardiovascular dysfunction in adult offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R127–133. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00354.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koukkou E, Ghosh P, Lowy C, Poston L. Offspring of normal and diabetic rats fed saturated fat in pregnancy demonstrate vascular dysfunction. Circulation. 1998;98:2899–2904. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samuelsson AM, Matthews PA, Argenton M, Christie MR, McConnell JM, Jansen EH, Piersma AH, Ozanne SE, Twinn DF, Remacle C, Rowlerson A, Poston L, Taylor PD. Diet-induced obesity in female mice leads to offspring hyperphagia, adiposity, hypertension, and insulin resistance: a novel murine model of developmental programming. Hypertension. 2008;51:383–392. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ogden CL, Yanovski SZ, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. The epidemiology of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2087–2102. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brawley L, Itoh S, Torrens C, Barker A, Bertram C, Poston L, Hanson M. Dietary protein restriction in pregnancy induces hypertension and vascular defects in rat male offspring. Pediatr Res. 2003;54:83–90. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000065731.00639.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan IY, Taylor PD, Dekou V, Seed PT, Lakasing L, Graham D, Dominiczak AF, Hanson MA, Poston L. Gender-linked hypertension in offspring of lard-fed pregnant rats. Hypertension. 2003;41:168–175. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000047511.97879.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pham TD, MacLennan NK, Chiu CT, Laksana GS, Hsu JL, Lane RH. Uteroplacental insufficiency increases apoptosis and alters p53 gene methylation in the full-term IUGR rat kidney. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R962–970. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00201.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Douglas-Denton RN, McNamara BJ, Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Bertram JF. Does nephron number matter in the development of kidney disease? Ethn Dis. 2006;16:S2-40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fowden AL, Forhead AJ. Endocrine mechanisms of intrauterine programming. Reproduction. 2004;127:515–526. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langley-Evans SC. Intrauterine programming of hypertension by glucocorticoids. Life Sci. 1997;60:1213–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(96)00611-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ortiz LA, Quan A, Zarzar F, Weinberg A, Baum M. Prenatal dexamethasone programs hypertension and renal injury in the rat. Hypertension. 2003;41:328–334. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000049763.51269.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manikkam M, Crespi EJ, Doop DD, Herkimer C, Lee JS, Yu S, Brown MB, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V. Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone excess leads to fetal growth retardation and postnatal catch-up growth in sheep. Endocrinology. 2004;145:790–798. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crespi EJ, Steckler TL, Mohankumar PS, Padmanabhan V. Prenatal exposure to excess testosterone modifies the developmental trajectory of the insulin-like growth factor system in female sheep. J Physiol. 2006;572:119–130. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.King AJ, Olivier NB, Mohankumar PS, Lee JS, Padmanabhan V, Fink GD. Hypertension caused by prenatal testosterone excess in female sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E1837–1841. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00668.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Woods LL, Ingelfinger JR, Rasch R. Modest maternal protein restriction fails to program adult hypertension in female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;289:R1131–1136. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00037.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Anderson CM, Lopez F, Zimmer A, Benoit JN. Placental insufficiency leads to developmental hypertension and mesenteric artery dysfunction in two generations of Sprague-Dawley rat offspring. Biol Reprod. 2006;74:538–544. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.045807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ojeda NB, Grigore D, Yanes LL, Iliescu R, Robertson EB, Zhang H, Alexander BT. Testosterone contributes to marked elevations in mean arterial pressure in adult male intrauterine growth restricted offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R758–763. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00311.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ojeda NB, Grigore D, Robertson EB, Alexander BT. Estrogen protects against increased blood pressure in postpubertal female growth restricted offspring. Hypertension. 2007;50:679–685. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.091785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lloyd-Jones D, McDermott M, Meigs J, Moy C, Nichol G, O'Donnell CJ, Roger V, Rumsfeld J, Sorlie P, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Hong Y. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2007 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:e69–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reckelhoff JF. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension. 2001;37:1199–1208. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hinojosa-Laborde C, Craig T, Zheng W, Ji H, Haywood JR, Sandberg K. Ovariectomy augments hypertension in aging female Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2004;44:405–409. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000142893.08655.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chappell MC, Yamaleyeva LM, Westwood BM. Estrogen and salt sensitivity in the female mRen(2).Lewis rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;291:R1557–1563. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00051.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Reckelhoff JF, Zhang H, Granger JP. Testosterone exacerbates hypertension and reduces pressure-natriuresis in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1998;31:435–439. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.31.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Martin DS, Biltoft S, Redetzke R, Vogel E. Castration reduces blood pressure and autonomic venous tone in male spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2229–2236. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000191903.19230.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Teixeira CV, Silandre D, de Souza Santos AM, Delalande C, Sampaio FJ, Carreau S, da Fonte Ramos C. Effects of maternal undernutrition during lactation on aromatase, estrogen, and androgen receptors expression in rat testis at weaning. J Endocrinol. 2007;192:301–311. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Allvin K, Ankarberg-Lindgren C, Fors H, Dahlgren J. Elevated serum levels of estradiol, dihydrotestosterone and inhibin B in adult males born small for gestational age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1743. [Epub ahead of print] PMID: 18252790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cicognani A, Alessandroni R, Pasini A, Pirazzoli P, Cassio A, Barbieri E, Cacciari E. Low birth weight for gestational age and subsequent male gonadal function. J Pediatr. 2002;141:376–379. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.126300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jensen RB, Vielwerth S, Larsen T, Greisen G, Veldhuis J, Juul A. Pituitary-gonadal function in adolescent males born appropriate or small for gestational age with or without intrauterine growth restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1353–1357. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zambrano E, Rodriguez-Gonzalez GL, Guzman C, Garcia-Becerra R, Boeck L, Diaz L, Menjivar M, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW. A maternal low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation in the rat impairs male reproductive development. J Physiol. 2005;563:275–284. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.078543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Leonhardt M, Lesage J, Croix D, Dutriez-Casteloot I, Beauvillain JC, Dupouy JP. Effects of perinatal maternal food restriction on pituitary-gonadal axis and plasma leptin level in rat pup at birth and weaning and on timing of puberty. Biol Reprod. 2003;68:390–400. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.102.003269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Da Silva P, Aitken RP, Rhind SM, Racey PA, Wallace JM. Influence of placentally mediated fetal growth restriction on the onset of puberty in male and female lambs. Reproduction. 2001;122:375–383. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1220375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rae MT, Kyle CE, Miller DW, Hammond AJ, Brooks AN, Rhind SM. The effects of undernutrition, in utero, on reproductive function in adult male and female sheep. Anim Reprod Sci. 2002;72:63–71. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4320(02)00068-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Weissenbruch MM, Engelbregt MJ, Veening MA, Delemarre-van de Waal HA. Fetal nutrition and timing of puberty. Endocr Dev. 2005;8:15–33. doi: 10.1159/000084084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guzman C, Cabrera R, Cardenas M, Larrea F, Nathanielsz PW, Zambrano E. Protein restriction during fetal and neonatal development in the rat alters reproductive function and accelerates reproductive ageing in female progeny. J Physiol. 2006;572:97–108. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hall JE, Brands MW, Henegar JR. Angiotensin II and long-term arterial pressure regulation: the overriding dominance of the kidney. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(Suppl 12):S258–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manning J, Vehaskari VM. Low birth weight-associated adult hypertension in the rat. Pediatr Nephrol. 2001;16:417–422. doi: 10.1007/s004670000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Langley-Evans SC, Jackson AA. Captopril normalises systolic blood pressure in rats with hypertension induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Comp Biochem Physiol A Physiol. 1995;110:223–228. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(94)00177-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sahajpal V, Ashton N. Renal function and angiotensin AT1 receptor expression in young rats following intrauterine exposure to a maternal low-protein diet. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:607–614. doi: 10.1042/CS20020355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ceravolo GS, Franco MC, Carneiro-Ramos MS, Barreto-Chaves ML, Tostes RC, Nigro D, Fortes ZB, Carvalho MH. Enalapril and losartan restored blood pressure and vascular reactivity in intrauterine undernourished rats. Life Sci. 2007;80:782–787. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ruster M, Sommer M, Stein G, Bauer K, Walter B, Wolf G, Bauer R. Renal Angiotensin receptor type 1 and 2 upregulation in intrauterine growth restriction of newborn piglets. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;182:106–114. doi: 10.1159/000093065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pladys P, Lahaie I, Cambonie G, Thibault G, Le NL, Abran D, Nuyt AM. Role of brain and peripheral angiotensin II in hypertension and altered arterial baroreflex programmed during fetal life in rat. Pediatr Res. 2004;55:1042–1049. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000127012.37315.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grigore D, Ojeda NB, Robertson EB, Dawson AS, Huffman CA, Bourassa EA, Speth RC, Brosnihan KB, Alexander BT. Placental insufficiency results in temporal alterations in the renin angiotensin system in male hypertensive growth restricted offspring. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;293(2):R804–R811. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00725.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Song J, Kost CK, Jr., Martin DS. Androgens augment renal vascular responses to ANG II in New Zealand genetically hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1608–1615. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00364.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen YF, Naftilan AJ, Oparil S. Androgen-dependent angiotensinogen and renin messenger RNA expression in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1992;19:456–463. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.19.5.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gallagher PE, Li P, Lenhart JR, Chappell MC, Brosnihan KB. Estrogen regulation of angiotensin-converting enzyme mRNA. Hypertension. 1999;33:323–328. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.1.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nickenig G, Baumer AT, Grohe C, Kahlert S, Strehlow K, Rosenkranz S, Stablein A, Beckers F, Smits JF, Daemen MJ, Vetter H, Bohm M. Estrogen modulates AT1 receptor gene expression in vitro and in vivo. Circulation. 1998;97:2197–2201. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.22.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ferrario CM, Chappell MC. Novel angiotensin peptides. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2720–2727. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-4243-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brosnihan KB, Senanayake PS, Li P, Ferrario CM. Bi-directional actions of estrogen on the renin-angiotensin system. Braz J Med Biol Res. 1999;32:373–381. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x1999000400001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.DiBona GF, Kopp UC. Neural control of renal function. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:75–197. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hall JE, Guyton AC, Brands MW. Pressure-volume regulation in hypertension. Kidney Int Suppl. 1996;55:S35–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.I.Jzerman R, Stehouwer CD, de Geus EJ, van Weissenbruch MM, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, Boomsma DI. Low birth weight is associated with increased sympathetic activity: dependence on genetic factors. Circulation. 2003;108:566–571. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000081778.35370.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Phillips DI, Barker DJ. Association between low birthweight and high resting pulse in adult life: is the sympathetic nervous system involved in programming the insulin resistance syndrome? Diabet Med. 1997;14:673–677. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199708)14:8<673::AID-DIA458>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Boguszewski MC, Johannsson G, Fortes LC, Sverrisdottir YB. Low birth size and final height predict high sympathetic nerve activity in adulthood. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1157–1163. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200406000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Weitz G, Deckert P, Heindl S, Struck J, Perras B, Dodt C. Evidence for lower sympathetic nerve activity in young adults with low birth weight. J Hypertens. 2003;21:943–950. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200305000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Petry CJ, Dorling MW, Wang CL, Pawlak DB, Ozanne SE. Catecholamine levels and receptor expression in low protein rat offspring. Diabet Med. 2000;17:848–853. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hiraoka T, Kudo T, Kishimoto Y. Catecholamines in experimentally growth-retarded rat fetus. Asia Oceania J Obstet Gynaecol. 1991;17:341–348. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.1991.tb00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Jones CT, Robinson JS. Studies on experimental growth retardation in sheep. Plasma catecholamines in fetuses with small placenta. J Dev Physiol. 1983;5:77–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Alexander BT, Hendon AE, Ferril G, Dwyer TM. Renal denervation abolishes hypertension in low-birth-weight offspring from pregnant rats with reduced uterine perfusion. Hypertension. 2005;45:754–758. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000153319.20340.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dampney RA, Horiuchi J, Killinger S, Sheriff MJ, Tan PS, McDowall LM. Long-term regulation of arterial blood pressure by hypothalamic nuclei: some critical questions. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2005;32:419–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2005.04205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wilcox CS. Reactive oxygen species: roles in blood pressure and kidney function. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2002;4:160–166. doi: 10.1007/s11906-002-0041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. Reactive oxygen species in vascular biology: implications in hypertension. Histochem Cell Biol. 2004;122:339–352. doi: 10.1007/s00418-004-0696-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Franco MC, Kawamoto EM, Gorjao R, Rastelli VM, Curi R, Scavone C, Sawaya AL, Fortes ZB, Sesso R. Biomarkers of oxidative stress and antioxidant status in children born small for gestational age: evidence of lipid peroxidation. Pediatr Res. 2007;62:204–208. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3180986d04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Stewart T, Jung FF, Manning J, Vehaskari VM. Kidney immune cell infiltration and oxidative stress contribute to prenatally programmed hypertension. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2180–2188. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cambonie G, Comte B, Yzydorczyk C, Ntimbane T, Germain N, Le NL, Pladys P, Gauthier C, Lahaie I, Abran D, Lavoie JC, Nuyt AM. Antenatal antioxidant prevents adult hypertension, vascular dysfunction, and microvascular rarefaction associated with in utero exposure to a low-protein diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292:R1236–1245. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00227.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chabrashvili T, Kitiyakara C, Blau J, Karber A, Aslam S, Welch WJ, Wilcox CS. Effects of ANG II type 1 and 2 receptors on oxidative stress, renal NADPH oxidase, and SOD expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285:R117–124. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00476.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bagby SP. Maternal nutrition, low nephron number, and hypertension in later life: pathways of nutritional programming. J Nutr. 2007;137:1066–1072. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.4.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Woods LL. Neonatal uninephrectomy causes hypertension in adult rats. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:R974–978. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1999.276.4.R974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Armitage JA, Lakasing L, Taylor PD, Balachandran AA, Jensen RI, Dekou V, Ashton N, Nyengaard JR, Poston L. Developmental programming of aortic and renal structure in offspring of rats fed fat-rich diets in pregnancy. J Physiol. 2005;565:171–184. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Guyton AC, Coleman TG, Cowley AV, Jr., Scheel KW, Manning RD, Jr., Norman RA., Jr Arterial pressure regulation. Overriding dominance of the kidneys in long-term regulation and in hypertension. Am J Med. 1972;52:584–594. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(72)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hoy WE, Rees M, Kile E, Mathews JD, Wang Z. A new dimension to the Barker hypothesis: low birthweight and susceptibility to renal disease. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1072–1077. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Fan ZJ, Lackland DT, Lipsitz SR, Nicholas JS. The association of low birthweight and chronic renal failure among Medicaid young adults with diabetes and/or hypertension. Public Health Rep. 2006;121:239–244. doi: 10.1177/003335490612100304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li S, Chen SC, Shlipak M, Bakris G, McCullough PA, Sowers J, Stevens L, Jurkovitz C, McFarlane S, Norris K, Vassalotti J, Klag MJ, Brown WW, Narva A, Calhoun D, Johnson B, Obialo C, Whaley-Connell A, Becker B, Collins AJ. Low birth weight is associated with chronic kidney disease only in men. Kidney Int. 2008;73:637–642. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nwagwu MO, Cook A, Langley-Evans SC. Evidence of progressive deterioration of renal function in rats exposed to a maternal low-protein diet in utero. Br J Nutr. 2000;83:79–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Regina S, Lucas R, Miraglia SM, Zaladek Gil F, Machado Coimbra T. Intrauterine food restriction as a determinant of nephrosclerosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:467–476. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.22088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gil FZ, Lucas SR, Gomes GN, Cavanal Mde F, Coimbra TM. Effects of intrauterine food restriction and long-term dietary supplementation with L-arginine on age-related changes in renal function and structure of rats. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:724–731. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000159514.06939.7E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]