Abstract

Cellular determinants of the germline selectively accumulate in germ cell precursors and influence cell fate during early development in many organisms. Zhang et al. (2009) now report that targeted autophagy mediated by the SEPA-1 protein depletes germplasm proteins from somatic cells during early development of the nematode.

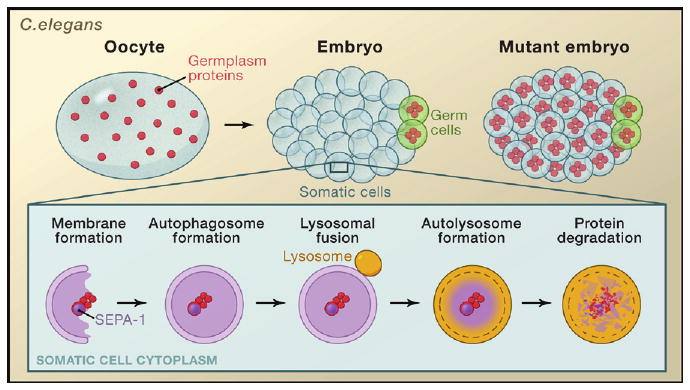

During embryonic development, cells are specified to become either nonreproductive somatic cells or germ cells that are capable of producing the next generation. Germline determinants in the cytoplasm (germplasm) comprising protein and RNA accumulate in developing germ cells but are absent in somatic cells during early animal development (Strome and Lehmann, 2007) (Figure 1). This restriction of germplasm to germ cells is partly accomplished by differential localization of this material in the developing animal. Studies in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans have shown that the loss of germplasm proteins in somatic cells is regulated by ubiquitin conjugation factors (DeRenzo et al., 2003), indicating that the ubiquitin-proteasome system is involved in degrading germplasm in somatic cells. In this issue, Zhang et al. (2009) provide evidence that autophagy directed by the SEPA-1 protein is also required for clearance of germplasm proteins from somatic cells in the developing nematode embryo.

Figure 1. Autophagy Regulates Clearance of Germplasm Proteins.

Germplasm proteins (red) are widely distributed in the C. elegans oocyte but become restricted to the germ cells (green) early during embryogenesis. Germplasm proteins are selectively degraded by autophagy in somatic cells (blue). The SEPA-1 protein (purple) is required for targeting of germplasm proteins to the autophagosome for degradation by the autolysosome. Mutant worm embryos defective in autophagy fail to degrade germplasm proteins and thus retain these proteins in both somatic cells and germ cells.

Autophagy or “self-eating” is a catabolic process that delivers cytoplasmic materials, including proteins and organelles, to the lysosomes for degradation. Whereas the ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates the degradation of many short-lived proteins, autophagy is used to degrade long-lived cellular structures and proteins. Three forms of autophagy exist: Macro-autophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy, and micro-autophagy. Of these processes, macro-autophagy is the most studied. During macro-autophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy), cytoplasmic cargo is enclosed in double-membraned vesicles called autophagosomes that are subsequently delivered to the lysosome for degradation by hydrolases (Mizushima, 2007) (Figure 1). Pioneering studies in yeast identified autophagy (atg) genes that encode proteins required for this process. Many of these atg genes have conserved functions in higher animals (Mizushima, 2007) where autophagy has been implicated in many processes, including the clearance of protein aggregates (Mizushima et al., 2008). Animals lacking atg gene function accumulate ubiquitin-positive inclusions in the brain, have shortened life spans, and develop neurological disorders (Rubinsztein, 2006). Studies of patients with protein aggregation disorders and animal models of these disorders reveal that autophagy can protect cells from these toxic protein aggregates and can regulate the clearance of abnormal protein aggregates in the aging nervous system. Now Zhang and colleagues provide evidence that autophagy can regulate the clearance of protein aggregates that are involved in the specification of germ cell fate during normal embryonic development. Their results suggest that autophagy may selectively target germplasm proteins for degradation by lysosomes (Figure 1).

In C. elegans, the germplasm contains P granules, a specialized type of RNA and protein aggregate that regulates germ cell fate. To identify genes that are required for the selective loss of P granule proteins in somatic cells of the worm embryo, Zhang et al. performed a genome-wide RNA interference (RNAi) screen. Surprisingly, they find that the autophagy gene lgg-1 (atg8 in yeast) is required for the clearance of P granule proteins in these somatic cells. Strikingly, disruption of other worm orthologs of yeast autophagy genes (atg1, atg3, atg4, atg7, atg10, atg12, and atg18) also results in the loss of P granule protein degradation in somatic cells. The persistent P granule proteins in somatic cells of lgg-1 worm embryos defective in autophagy are likely to be maternally derived because P granule component RNA transcript levels are not increased in these mutants.

How does the bulk degradation process of autophagy specifically target P granule components in somatic cells but not in germ cells? To investigate this question, Zhang and colleagues conducted a genetic screen to identify mutations that suppress the accumulation of P granule components in somatic cells of autophagy mutants. They find that mutations in the sepa-1 (suppressor of ectopic P granule in autophagy mutants 1) gene suppress the formation of P granule protein aggregates in the somatic cells of autophagy mutants without affecting P granules in germline cells. In addition, there is no decrease in P granule proteins in late-stage sepa-1 mutant worm embryos, indicating that the protein encoded by sepa-1 is required for degradation of these factors. The SEPA-1 protein is rich in helical domains and also contains a KIX protein interaction domain. Biochemical studies by Zhang et al. indicate that SEPA-1 self-associates. Immunofluorescence staining reveals that aggregates of SEPA-1 accumulate specifically in the somatic cells of developing embryos and that this staining disappears at late stages of embryogenesis.

These data raise the possibility that SEPA-1 is associated with and regulates autophagy. The authors find that clearance of SEPA-1 in somatic cells requires the autophagy genes lgg-1, atg3, and atg7. SEPA-1 aggregates colocalize and directly interact with LGG-1. In support of a role for SEPA-1 in targeting P granule components to autophagosomes, Zhang and colleagues observe that SEPA-1 aggregates also colocalize with P granule proteins and that the SEPA-1 protein physically interacts with the P granule protein PGL-3. PGL-3 is required for the accumulation of the P granule protein PGL-1 in somatic cells of autophagy-deficient embryos. Interestingly, the formation of SEPA-1 aggregates does not require either PGL-1 or PGL-3. Therefore, it appears that SEPA-1 mediates the recruitment of P granule components to autophagosomes by aggregating and physically interacting with both LGG-1 and specific P granule proteins (Figure 1).

The sequestration and degradation of cytoplasmic components by autophagy during embryogenesis present interesting questions about the regulation of autophagy, germplasm protein clearance, and development. Worms lacking proteins encoded by atg3, atg7, and atg8 develop normally; thus, the persistence of certain P granule components in somatic cells is clearly not sufficient to transform the fate of these cells to that of germ cells. These observations are consistent with the complementary involvement of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the degradation of P granule components (DeRenzo et al., 2003). Interplay between the ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy has been observed in the context of protein aggregation disorders (Pandey et al., 2007), suggesting that autophagy may enable the degradation of complexes that impair the ubiquitin-proteasome system. However, the degradation of SEPA-1 and the P granule component PGL-1 in C. elegans is unaffected when the proteasome is impaired, indicating that in this case, autophagy degrades P granule components in a manner independent of proteasome function. These data indicate that specific P granule-associated proteins are degraded by independent catabolic mechanisms. Additional studies are needed to understand why both autophagy and the ubiquitin-proteasome system are required to degrade these factors.

Autophagy is considered to be a bulk degradation process that is attenuated in growing and dividing cells (Eskelinen et al., 2002). The rapid cell division and new membrane formation that occur during early C. elegans embryonic development would likely be in conflict with the non-specific bulk degradation of cytoplasmic components mediated by autophagy. Thus, autophagy of P granule proteins in the nematode embryo may require a specific autophagosome targeting mechanism, supporting the notion that targeted degradation of specific proteins by autophagy is a more prevalent phenomenon than was previously thought (van der Vaart et al., 2008). Significantly, SEPA-1 appears to be functionally similar to the mammalian p62 protein in mediating the recognition of protein aggregates by the autophagic machinery (Komatsu et al., 2007). Zhang and colleagues further describe multiple SEPA-1-related proteins in C. elegans that appear to be targets of autophagy, thus suggesting the possibility that this protein family plays a broad role in the recruitment of cargo to autophagosomes. Notably, mutations in sepa-1 do not affect other autophagy-associated processes in C. elegans, including the clearance of polyglutamine protein aggregates. Future studies are required to determine the importance of SEPA-1-related proteins in the regulation of autophagy in other C. elegans cell types, and whether the role for autophagy in eliminating germplasm determinants from somatic cells is conserved in other organisms.

Acknowledgments

I thank the NIH (GM059136 and GM079431) for support.

References

- DeRenzo C, Reese KJ, Seydoux G. Nature. 2003;424:685–689. doi: 10.1038/nature01887.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen EL, Prescott AR, Cooper J, Brachmann SM, Wang L, Tang X, Backer JM, Lucocq JM. Traffic. 2002;3:878–893. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.31204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu M, Waguri S, Koike M, Sou YS, Ueno T, Hara T, Mizushima N, Iwata J, Ezaki J, Murata S, et al. Cell. 2007;131:1149–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2861–2873. doi: 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey UB, Nie Z, Batlevi Y, McCray BA, Ritson GP, Nedelsky NB, Schwartz SL, DiProspero NA, Knight MA, Schuldiner O, et al. Nature. 2007;447:859–863. doi: 10.1038/nature05853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC. Nature. 2006;443:780–786. doi: 10.1038/nature05291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strome S, Lehmann R. Science. 2007;316:392–393. doi: 10.1126/science.1140846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Vaart A, Mari M, Reggiori F. Traffic. 2008;9:281–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Yan L, Zhou Z, Yang P, Tian E, Zhang K, Zhao Y, Li Z, Song B, Han J, et al. Cell. 2009;(this issue) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]