Abstract

The distribution of Aedes aegypti (L.) in Australia is currently restricted to northern Queensland, but it has been more extensive in the past. In this study, we evaluate the genetic structure of Ae. aegypti populations in Australia and Vietnam and consider genetic differentiation between mosquitoes from these areas and those from a population in Thailand. Six microsatellites and two exon primed intron crossing markers were used to assess isolation by distance across all populations and also within the Australian sample. Investigations of founder effects, amount of molecular variation between and within regions and comparison of FST values among Australian and Vietnamese populations were made to assess the scale of movement of Ae. aegypti. Genetic control methods are under development for mosquito vector populations including the dengue vector Ae. aegypti. The success of these control methods will depend on the population structure of the target species including population size and rates of movement among populations. Releases of modified mosquitoes could target local populations that show a high degree of isolation from surrounding populations, potentially allowing new variants to become established in one region with eventual dispersal to other regions.

Keywords: Aedes aegypti, dengue, population structure, gene flow

New methods of controlling mosquito-borne diseases are being developed and include genetic manipulation to alter the transmission of mosquito-borne pathogens (James 2005). Attempts to modify transmission of the dengue virus in the vectors, Aedes aegypti (L.) and Aedes albopictus (Skuse) are being made. Transgenic Ae. aegypti with reduced vector competence for DENV-2 viruses have been developed using RNA interference techniques (Franz et al. 2006). Ae. aegypti also is being engineered to contain repressible dominant lethal genes for use in areawide population control based on the sterile insect technique (Yakob et al. 2008).

In another approach, the widely distributed insect endosymbiont Wolbachia is being used to modify Aedes species. So far, Wolbachia has been introduced into both Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus (Xi et al. 2005, Ruang-areerate and Kittayapong 2006, Xi et al. 2006) and establishment of life span-reducing strains of Wolbachia that were originally isolated from Drosophila (Sinkins and Gould 2006) is being attempted. Life span-reducing strains of Wolbachia are expected to decrease transmission of dengue, which only occurs in older females (Watts et al. 1987, Cook et al. 2006).

The success of Wolbachia-based control measures will depend on the size of the target population as well as levels of immigration of local mosquitoes. Therefore, it is critical that estimates of population structure are obtained in areas where releases are planned. Studies on the population structure of target mosquitoes including Ae. aegypti have been made, initially, to determine the appropriate size of the insecticide treatment area around dengue fever cases (Mousson et al. 2002), but they are now being intensified to address the requirements of new control methods for mosquitoes.

Initial studies of population structure of Ae. aegypti used allozymes (Pashley and Rai 1983, Failloux et al. 1995, DinardoMiranda and Contel 1996, Failloux et al. 2002). There are also a few studies in which amplified fragment length polymorphism markers are used (Ravel et al. 2001, Paupy et al. 2004a, Merrill et al. 2005) and a mitochondrial DNA study of Ae. aegypti in Thailand (Bosio et al. 2005). A set of microsatellite markers for Ae. aegypti was initially isolated by Huber et al. (2001) and used (sometimes in conjunction with isoenzymes) to demonstrate genetic differences among populations in Vietnam (Huber et al. 2002a,b) and other countries in Southeast Asia (Huber et al. 2004). However, a need for a larger set of robust microsatellite loci was identified and two other sets of microsatellite primers have been isolated but not yet used in extensive population surveys (Chambers et al. 2007, Slotman et al. 2007). These other sets of markers should provide an extensive resource for population genetic surveys.

Low rates of movement are expected in populations of Ae. aegypti because this species has a very close association with humans and shelters in indoor habitats (Reiter 2007). Some local dispersal occurs as females seek a bloodmeal and as they engage in “skip oviposition” (Reiter 2007)—distributing a small number of eggs among many containers. Significant genetic differentiation at the local scale in Cambodian populations of Ae. aegypti detected by both microsatellites and allozymes (Paupy et al. 2003, 2004a,b) is evidence of low rates of movement in this species. Genetic differentiation over a few kilometers was identified in North Cameroon (Paupy et al. 2008). Longer distance movement, although not as common, also can take place. It is thought to be the cause of genetic similarity between populations of Ae. aegypti that are separated by hundreds of kilometers, as occurs in Ho Chi Minh City and Phnom Penh (Huber et al. 2004). Long-distance movement probably arises by translocation of desiccation resistant mosquito eggs, aquatic stages, or both in containers moved by humans.

Here, we examine the population genetic structure of Ae. aegypti in Australia to determine the degree of isolation of populations and also to compare variability in Australian samples with those from Vietnam and Thailand. Ae. aegypti probably arrived in Australia during the mid-nineteenth century. Currently, it maintains a stronghold in Queensland with southern and western limits to its distribution, although it was more widely distributed in the past (O'Gower 1956). It is currently present year-round in urban areas of northern Queensland, Australia (Sinclair 1992). Outbreaks of dengue fever have occurred regularly in northern Queensland since 1990 (Ritchie et al. 2004, Hanna et al. 2006).

After evaluation of the available microsatellite markers, we chose to use those markers that showed optimal performance under conditions in our laboratory. The final selection of markers was made from those of Chambers et al. (2007) and Slotman et al. (2007), and we also isolated three new markers from the Ae. aegypti genome (http://aaegypti.vectorbase.org), namely, another microsatellite marker and two exon primed intron crossing (EPIC) markers. EPIC markers (Exon-Primed Intron Crossing markers) flank the coding regions of single copy genes and are used for detection of polymorphisms across noncoding regions. This is the first study to use EPIC markers in mosquito population work although they have now been applied successfully to investigate population structure in some other insects (He and Haymer 1997, Mun et al. 2003). Implications of the results are discussed in light of attempts to introduce new control options for mosquitoes to suppress transmission of pathogens.

Materials and Methods

Mosquito Collections

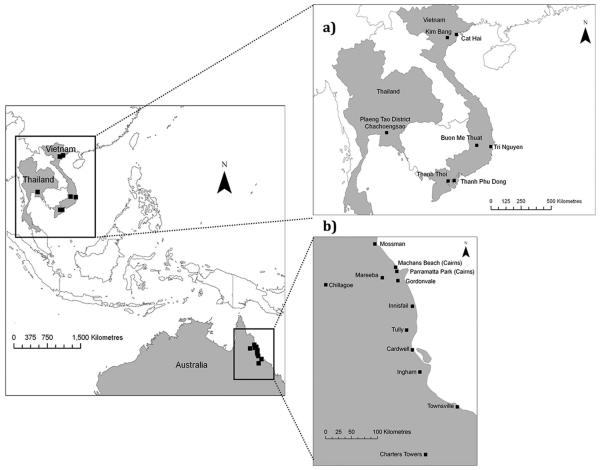

Ae. aegypti were sampled from 12 locations in far north Queensland in Australia. These locations were made up of three inland and nine coastal locations, including two suburbs (Parramatta Park and Machans Beach) within Cairns (Table 1; Fig. 1). The greatest distance between Australian sample locations was 441 km between Charters Towers and Mossman.

Table 1.

Collection details of Ae. aegypti samples screened with eight nuclear markers from Australia, Thailand, and Vietnam (wet season 2006)

| Country | Location | Life stage | Sample size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Parramatta Park, Cairns, Queensland | Adult/larval | 32 |

| Townsville, Queensland | Adult | 35 | |

| Charters Towers, Queensland | Adult/larval | 29 | |

| Ingham, Queensland | Adult/larval | 48 | |

| Machans Beach, Cairns, Queensland | Adult | 48 | |

| Innisfail, Queensland | Larval | 46 | |

| Chillagoe, Queensland | Adult/larval | 43 | |

| Tully, Queensland | Larval | 44 | |

| Gordonvale, Queensland | Larval | 44 | |

| Mareeba, Queensland | Larval | 36 | |

| Cardwell, Queensland | Adult/larval | 44 | |

| Mossman, Queensland | Larval | 31 | |

| Thailand | Plaeng Yao District, Chachoengsao Province | Adult | 48 |

| Vietnam | Cat Hai, Hai Phong, Northern | Adult | 22 |

| Kim Bang, Ha Nam, Northern | Adult | 19 | |

| Tri Nguyen, Khanh Hoa, Central | Adult | 52 | |

| Buon Me Thuat, Dak Lak, Highland | Adult | 38 | |

| Thanh Phu Dong, Ben Tre, Southern | Adult | 30 | |

| Thanh Thoi, Vinh Long, Southern | Adult | 19 |

Fig. 1.

Map of areas where Ae. aegypti was sampled in Australia, Vietnam, and Thailand. Inset figures: (a) collection sites in Thailand and Vietnam and (b) collection sites in north Queensland.

The inland sites were located in the dry tropics of north Queensland, with annual precipitation ranging from 600 to 900 mm and daily minimal/maximal temperatures of ≈17–31°C; annual rainfall in the wet tropics sites ranges from 2,000 to 4,500 mm, with average daily minimal/maximal temperature of 19–29°C (data from Australian Bureau of Meteorology). Mosquitoes were sampled during the wet season, from March to May 2006. Samples were collected using BG-Sentinel traps (run with or without dry-ice) (Williams et al. 2006), ovitraps (Ritchie et al. 2004), or by pipetting larvae from flooded containers. Attempts were made to collect at least 50 live individuals per location. To minimize the number of siblings in the analysis, only five adults per BG-Sentinel trap and one larva per ovitrap or container were used. Live specimens (larvae or adults) were killed by freezing or were submerged directly in absolute ethanol. Samples were preserved in absolute ethanol and stored at −20°C before analysis.

Female Ae. aegypti adults were collected from six locations in Vietnam: Cat Hai, Hai Phong Province (Northern Vietnam); Kim Bang, Ha Nam Province (Northern Vietnam); Buon Me Thuat, Dak Lak Province (Central Highlands), Tri Nguyen, Khanh Hoa Province (Central Vietnam); Thanh Thoi, Vinh Long Province (Southern Vietnam); Thanh Phu Dong, Ben Tre Province (Southern Vietnam). Collections were made inside houses using mechanical aspirators (Clarke Mosquito Control, Roselle, IL) between May and August 2006. Individual female mosquitoes were killed by freezing at −20°C, identified to species, and then stored in absolute ethanol at −60°C until processed. A sample of adult Ae. aegypti was taken from Plaeng Yao District, Chachoengsao Province, Thailand, from inside houses by using mechanical aspirators.

Genetic Markers

Eight genetic markers were used to screen for variation in populations of Ae. aegypti (Table 1). One microsatellite marker (Gyp8) and two ribosomal protein EPIC markers (Rps20b and RpL30a) were developed for this study. The ribosomal protein markers were developed by identifying proteins from the unannotated genomic sequence of Ae. aegypti and developing primers for those sequences that had an intron that was within ≈300 bp of exons. Rps20b (78148872 gb AAGE02016649.1 Aedes aegypti strain Liverpool cont1.16649, whole genome shotgun sequence) spans position 681–930. RpL30a (78157656 gb AAGE02008136.1 Aedes aegypti strain Liverpool cont1.8136) spans position 271–468. The Gyp8 microsatellite marker also was developed from sequences taken from the unannotated genomic sequence of Ae. aegypti (contig 1.12955, GenBank accession 78152577, position 29289–29470). A further two microsatellite loci developed by Slotman et al. (2007) (AC1 and AG5) and three loci developed by Chambers et al. (2007) (BbA10, BbH08, and BbB07) also were used to screen samples.

Amplification of microsatellites by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) took place in a volume of 10 μl with 2 μl of genomic DNA extracted using either a cetyltrimethylammonium bromide/chloroform method (Weeks et al. 2002) or a Chelex 100 Resin (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) method (Endersby et al. 2005). Primer concentrations of 0.03 μM (forward primer end labeled with [γ33-P]ATP), 0.1 μM (unlabeled forward primer), and 0.4 μM (reverse primer) were used. The reaction mix contained 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dNTPs, 0.5 mg/ml purified bovine serum albumin (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), 1 μl of 10× PCR amplification buffer, and 0.4 U of Taq polymerase (New England Biolabs). PCR cycling conditions were as follows: AC1, AG5: denaturation (10 min, 94°C), 35 cycles of 94°C (30 s), annealing (30 s) 55°C and extension at 72°C (30 s), with final extension at 72°C (5 min); BbA10, BbH08, BbB07: denaturation (5 min, 94°C), 30 cycles of 94°C (1 min), annealing (1 min) at 60°C and extension at 72°C (2 min), with final extension at 72°C (10 min); and Rps20b, Rpl30a, Gyp8: denaturation (5 min, 94°C), 35 cycles of 94°C (30 s), annealing (30 s) at 58°C and extension at 72°C (45 s), with final extension at 72°C (5 min). Fragments derived from PCR were separated through 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gels at 65 W for 2.5–3.5 h and exposed for >12 h to autoradiographic film.

Analysis

The following basic statistics were calculated for the genetic marker data using FSTAT, version 2.9.3 (Goudet 1995): allelic richness per population averaged over loci, Weir and Cockerham's measure of FIS, a global estimate of FST (with 95% confidence limits) (Weir and Cockerham 1984); population pairwise measures of FST and their significance determined using permutations; and pairs of loci tested for linkage disequilibrium using a log-likelihood ratio test. Measures of FST over all loci were used to estimate the level of gene flow among populations following the formula Nm = 1/4 (1/FST − 1) (Slatkin and Barton 1989), where N is the effective population size (the number of individuals contributing to the next generation) and m is the migration rate.

Estimates of observed (HO) and expected (HE) heterozygosity were determined using Genetic Data Analysis (GDA) (Lewis and Zaykin 2001) and deviations from Hardy–Weinberg (HW) equilibrium were tested using Genepop, version 3.4 (Raymond and Rousset 1995). Regression and Mantel tests of Slatkin's linearized FST transformation [FST/(1−FST)] (Rousset 1997), with the natural log of geographical distance were calculated using PopTools, version 2.6 (Hood 2002). Significance of Mantel tests was determined by permutation (10,000 randomizations).

An analysis of molecular variation (AMOVA) was performed in Arlequin, version 3.11 (Schneider et al. 2000) by using pairwise FST as the distance measure, with 10,000 permutations and missing data for loci set at 10%. The model for analysis partitioned variation among regions (Australia, Thailand, and Vietnam), among populations within regions, and within populations. A factorial correspondence analysis was used to summarize patterns of genetic differentiation between the populations sampled (Genetix, version 4.03) (Belkhir et al. 2004). We plotted the first two underlying factors that explain the majority of the variation in the multilocus genotypes.

A Bayesian analysis to estimate the number of populations within the sample data was made using STRUCTURE, version 2 (Pritchard et al. 2000). A burn-in length of 100,000 was chosen followed by 500,000 iterations and the simulation was run using the admixture model with allele frequencies correlated among populations. The number of populations within the data (K) is estimated by checking the fit of the model for a range of K values. The data consisted of nineteen samples so K values of 1–19 were tested with three runs for each value of K. We used the method of Evanno et al. (2005) to estimate the true K.

We used two indirect methods to estimate Ne for all populations in this study. The first method calculates the effective population size as Ne = HE/4ν(1 − HE) and follows the assumptions of the Infinite Alleles model (IAM) of evolution (Kimura and Crow 1964). The second method is based on the stepwise mutation model (SMM) (Ohta and Kimura 1973) and calculates the effective population size as Ne = [(1/(1 − HE)2) − 1]/8ν. The methods are based on models for the evolution of microsatellite loci, and we therefore only used data from the six microsatellite loci.

Results

Genetic Markers

Seventy alleles in total were found for the eight genetic markers. The highest number of alleles was found for the microsatellite locus BbB07 (18; Table 2). The EPIC marker RpL30a had the lowest number of alleles (three), whereas the other EPIC marker (RpS20b) showed similar numbers of alleles to the other microsatellite loci. Allelic richness averaged over loci was highest in the samples from Vietnam (Table 3), and the Australian samples consistently had lower numbers of alleles at each locus compared with the Vietnamese samples (P < 0.05 for all pairwise population comparisons using a Wilcoxon's signed rank test), although there was no significant difference between allele numbers in Australia and Thailand or Vietnam and Thailand. Observed and expected heterozygosities were moderately high in all populations sampled (HO ≈ 0.43–0.58; HE ≈ 0.42–0.59). Only one population had a significant FIS, with an excess of homozygotes (Ca Hai, Hai Phong, northern Vietnam). Similarly, this was the only population that was significantly out of HW equilibrium across loci. However, when locus BbB07 was removed from the analyses, this population was no longer out of HW equilibrium and did not show an excess of homozygotes (data not shown). The microsatellite locus BbB07 showed a lack of heterozygotes across all populations (Table 2), and this may reflect the presence of null alleles at this locus. No consistent linkage dis-equilibrium was found between any loci across all populations, with only three of 532 pairwise tests significant after corrections for multiple comparisons.

Table 2.

Genetic markers used to screen samples of Ae. aegypti from Australia, Thailand, and Vietnam collected during the wet season, 2006

| Locus | Type | Alleles | Marker origin | HE | HO | HW P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rps20b | EPIC | 6 | Present study | 0.4991 | 0.4930 | 0.2691 |

| RpL30a | EPIC | 3 | Present study | 0.1042 | 0.0979 | 0.9999 |

| Gyp8 | Msat | 7 | Present study | 0.7592 | 0.7120 | 0.0510 |

| AC1 | Msat | 8 | Slotman et al. (2007) | 0.6832 | 0.5991 | 0.4597 |

| AG5 | Msat | 11 | Slotman et al. (2007) | 0.7018 | 0.6213 | 0.1864 |

| BbA10 | Msat | 12 | Chambers et al. (2007) | 0.5327 | 0.4812 | 0.0417 |

| BbH08 | Msat | 5 | Chambers et al. (2007) | 0.2722 | 0.2702 | 0.9999 |

| BbB07 | Msat | 18 | Chambers et al. (2007) | 0.8329 | 0.7269 | <0.001* |

Expected (HE) and observed heterozygosity (HO) and HW P values are indicated over all populations.

Asterisk denotes significance after correcting for multiple comparisons using the Dunn–Sidak method (Zar 1996).

Table 3.

Ae. aegypti population statistics from screening with eight genetic markers

| Pop | Location | r | FIS | HE | HO | HW-P | NeIAM (NeSMM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Australia | Parramatta Park, Cairns, Queensland | 3.75 | −0.005 | 0.5534 | 0.5563 | 0.9804 | 95989 (153786) |

| Townsville, Queensland | 3.62 | 0.003 | 0.4707 | 0.4679 | 0.2988 | 58785 (76122) | |

| Charters Towers, Queensland | 4.11 | −0.016 | 0.5402 | 0.5489 | 0.1127 | 77382 (112087) | |

| Ingham, Queensland | 3.48 | 0.001 | 0.4422 | 0.4417 | 0.2826 | 52195 (64749) | |

| Machans Beach, Cairns, Queensland | 3.70 | 0.009 | 0.5375 | 0.5326 | 0.1712 | 85160 (128822) | |

| Innisfail, Queensland | 3.92 | 0.034 | 0.5237 | 0.5062 | 0.9754 | 75352 (107883) | |

| Chillagoe, Queensland | 3.01 | −0.075 | 0.4214 | 0.4526 | 0.5083 | 45051 (53229) | |

| Tully, Queensland | 3.66 | 0.062 | 0.5307 | 0.4980 | 0.0097 | 80992 (119731) | |

| Gordonvale, Queensland | 3.42 | −0.053 | 0.4979 | 0.5238 | 0.3670 | 68679 (94546) | |

| Mareeba, Queensland | 3.46 | −0.033 | 0.4503 | 0.4652 | 0.9999 | 54361 (68407) | |

| Cardwell, Queensland | 3.59 | −0.021 | 0.4699 | 0.4795 | 0.2135 | 58062 (74839) | |

| Mossman, Queensland | 3.50 | 0.078 | 0.4681 | 0.4321 | 0.3378 | 57973 (74682) | |

| Thailand | Plaeng Yao District, Chachoengsao Province | 4.09 | 0.044 | 0.5756 | 0.5507 | 0.3745 | 81848 (121573) |

| Vietnam | Cat Hai, Hai Phong, Northern | 4.53 | 0.164* | 0.5488 | 0.4606 | 0.0004* | 83457 (125072) |

| Kim Bang, Ha Nam, Northern | 4.87 | 0.114 | 0.5785 | 0.5141 | 0.0259 | 84667 (127731) | |

| Tri Nguyen, Khanh Hoa, Central | 4.33 | 0.045 | 0.5366 | 0.5125 | 0.0187 | 74929 (107016) | |

| Buon Me Thuat, Dak Lak, Highland | 4.41 | 0.096 | 0.5308 | 0.4803 | 0.3876 | 76729 (110727) | |

| Thanh Phu Dong, Ben Tre, Southern | 5.06 | 0.036 | 0.5758 | 0.5553 | 0.8587 | 102077 (168672) | |

| Thanh Thoi, Vinh Long, Southern | 4.81 | 0.023 | 0.5884 | 0.5754 | 0.8783 | 97966 (158552) |

Mean values over loci are indicated for allelic richness (r), inbreeding (FIS), expected (HE) and observed (HO) heterozygosities, Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium P values. Indirect estimates of Ne were calculated under the assumptions of an IAM and SMM by using a mutation rate of 6.3 × 10−6 (Shug et al. 1997).

Asterisk denotes significantly different from zero after corrections for multiple comparisons at the table-wide α = 0.05 level.

Population Differentiation

The estimate of FST over all populations was 0.069 (0.055–0.085; 99% confidence intervals [CIs]), which indicates that there is significant population differentiation between the samples screened here. An AMOVA showed significant differentiation between samples from Australia, Thailand, and Vietnam, as well as differences within populations from Australia and Vietnam (Table 4). The majority of the variation in the microsatellite loci was explained by variation within populations (90.9%; P < 0.001), whereas variation between regions (Australia, Thailand, and Vietnam) explained 5.4% (P < 0.001) of the variation and populations within regions explained 3.7% (P < 0.001). Population pairwise comparisons of FST revealed only 20 nonsignificant comparisons out of 171 (Table 5). The Thailand and Vietnam populations were differentiated from all Australian populations; however, the Vietnamese populations showed the least differentiation among themselves with 12 of 15 comparisons for the six populations being nonsignificant.

Table 4.

Analysis of molecular variation at eight molecular markers among three regions (Australia, Vietnam, and Thailand), among populations within regions and within populations of Ae. aegypti

| Source of variation | df | Sum of squares |

Variance components |

Fixation indices |

P value | % variation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among regions | 2 | 90.19 | 0.111 | 0.054 | <0.001 | 5.40 |

| Among populations within regions | 16 | 117.90 | 0.075 | 0.039 | <0.001 | 3.68 |

| Within populations | 1,397 | 2,605.06 | 1.865 | 0.091 | <0.001 | 90.93 |

| Total | 1,415 | 2,813.15 | 2.051 |

Table 5.

Pairwise population comparisons of Ae. aegypti from Australia, Thailand, and Vietnam

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parramatta | 0 | 0.0547 | 0.0483 | 0.0836 | 0.0081 | 0.0211 | 0.0783 | 0.0301 | 0.0152 | 0.0321 | 0.0433 | 0.0371 | 0.0802 | 0.0440 | 0.074 | 0.0725 | 0.0452 | 0.0404 | 0.0368 |

| 2. Townsville | 282.2 | 0 | 0.0437 | 0.0294 | 0.0689 | 0.0160 | 0.0741 | 0.0150 | 0.0608 | 0.0590 | 0.0062 | 0.0216 | 0.1027 | 0.1015 | 0.1266 | 0.1222 | 0.0921 | 0.1026 | 0.0989 |

| 3. Charters | 354.1 | 107.5 | 0 | 0.0909 | 0.0757 | 0.0404 | 0.1083 | 0.0355 | 0.0606 | 0.0764 | 0.0570 | 0.0505 | 0.0947 | 0.0846 | 0.1016 | 0.1188 | 0.0842 | 0.0846 | 0.0538 |

| 4. Ingham | 197.0 | 95.3 | 180.4 | 0 | 0.1023 | 0.0619 | 0.0536 | 0.0465 | 0.0737 | 0.0761 | 0.0482 | 0.0390 | 0.1009 | 0.1270 | 0.1314 | 0.1261 | 0.1084 | 0.1181 | 0.1040 |

| 5. Machans | 7.9 | 267.0 | 358.7 | 180.1 | 0 | 0.0318 | 0.1117 | 0.0556 | 0.0186 | 0.0421 | 0.0510 | 0.0396 | 0.0941 | 0.0749 | 0.1019 | 0.1013 | 0.0587 | 0.0596 | 0.0634 |

| 6. Innisfail | 72.2 | 207.0 | 302.9 | 122.6 | 63.2 | 0 | 0.084 | 0.0131 | 0.0284 | 0.0356 | 0.0293 | 0.0164 | 0.0973 | 0.076 | 0.1034 | 0.0999 | 0.0728 | 0.0778 | 0.0698 |

| 7. Chillagoe | 134.5 | 322.4 | 382.2 | 241.1 | 151.4 | 185.2 | 0 | 0.0884 | 0.0744 | 0.0745 | 0.0773 | 0.0683 | 0.1113 | 0.1169 | 0.1054 | 0.1161 | 0.0946 | 0.1082 | 0.0941 |

| 8. Tully | 114.0 | 200.4 | 283.3 | 112.5 | 81.9 | 59.2 | 140.9 | 0 | 0.0545 | 0.0629 | 0.0379 | 0.0219 | 0.0988 | 0.0922 | 0.1152 | 0.1182 | 0.1006 | 0.0907 | 0.0747 |

| 9. Gordonvale | 18.8 | 254.5 | 340.5 | 166.3 | 33.3 | 66.3 | 124.5 | 57.6 | 0 | 0.0093 | 0.0434 | 0.0320 | 0.0942 | 0.0598 | 0.0789 | 0.0926 | 0.0505 | 0.0571 | 0.0524 |

| 10. Mareeba | 37.2 | 310.8 | 395.5 | 222.6 | 56.3 | 116.2 | 114.5 | 112.3 | 56.3 | 0 | 0.0340 | 0.0343 | 0.1158 | 0.0526 | 0.0849 | 0.0993 | 0.0540 | 0.0667 | 0.0604 |

| 11. Cardwell | 151.7 | 121.2 | 212.9 | 33.4 | 146.8 | 90.2 | 215.3 | 81.1 | 133.3 | 189.6 | 0 | 0.0272 | 0.0985 | 0.0893 | 0.1184 | 0.1097 | 0.0716 | 0.0837 | 0.0870 |

| 12. Mossman | 65.1 | 354.6 | 439.3 | 266.4 | 94.2 | 156.9 | 129.3 | 156.2 | 100.2 | 44.0 | 233.4 | 0 | 0.102 | 0.1054 | 0.1200 | 0.1255 | 0.0904 | 0.0996 | 0.0827 |

| 13. Thailand | 5900.5 | 6095.3 | 6121.6 | 6021.2 | 5895.0 | 5951.8 | 5781.6 | 5920.6 | 5885.7 | 5838.8 | 5996.8 | 5805.0 | 0 | 0.0825 | 0.0529 | 0.0600 | 0.0459 | 0.0428 | 0.0264 |

| 14. Cat Hai, N | 5961.6 | 6186.7 | 6232.6 | 6104.6 | 5955.2 | 6016.4 | 5864.5 | 5995.9 | 5952.5 | 5900.2 | 6076.1 | 5861.4 | 1043.5 | 0 | 0.0213 | 0.0368 | 0.0159 | 0.0122 | 0.0244 |

| 15. Kim Bang, N | 6164.8 | 6338.8 | 6384.1 | 6256.9 | 6108.0 | 6169.1 | 6016.7 | 6148.3 | 6105.1 | 6052.9 | 6228.5 | 6014.2 | 1046.7 | 155.0 | 0 | 0.0312 | 0.0187 | 0.0099 | 0.0157 |

| 16. Tri Nguyen, C | 6058.1 | 6281.1 | 6325.5 | 6199.5 | 6051.7 | 6112.7 | 5959.1 | 6091.3 | 6048.5 | 5996.6 | 6171.4 | 5958.1 | 978.2 | 127.0 | 79.9 | 0 | 0.0088 | 0.0106 | 0.0293 |

| 17. Buon Me Thuat C | 5294.8 | 5502.4 | 5536.8 | 5424.8 | 5289.0 | 5347.7 | 5183.8 | 5320.5 | 5282.1 | 5232.9 | 5398.7 | 5197.1 | 714.2 | 912.4 | 1017.6 | 939.2 | 0 | 0.0028 | 0.0136 |

| 18. Thanh Phu Dong, S | 5282.4 | 5478.9 | 5506.6 | 5404.3 | 5276.9 | 5333.9 | 5164.4 | 5303.1 | 5267.8 | 5220.6 | 5379.6 | 5186.7 | 619.3 | 1178.1 | 1259.9 | 1180.0 | 326.3 | 0 | 0.0050 |

| 19. Thanh Thoi, S | 5321.1 | 5516.7 | 5543.8 | 5442.3 | 5315.6 | 5372.4 | 5202.6 | 5341.4 | 5306.3 | 5259.3 | 5417.8 | 5225.5 | 579.6 | 1179.5 | 1256.3 | 1176.5 | 352.2 | 45.6 | 0 |

Upper diagonal is pairwise FST estimates, below diagonal is pairwise geographic distance (km). Significance of FST estimates (obtained by 171,000 permutations) at the table-wide α = 0.05 level are indicated by normal type (bold type indicates nonsignificance).

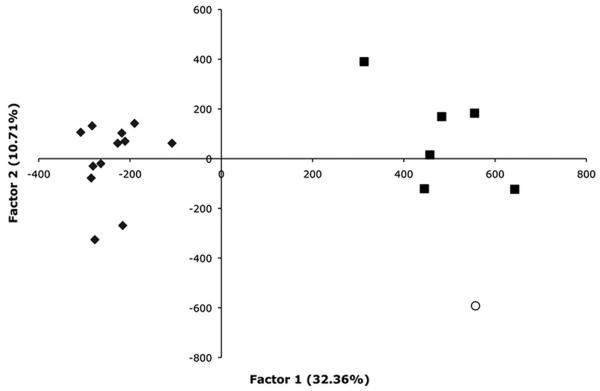

The first three axes in the factorial correspondence analysis at the population level explained 32.4, 10.7, and 9.1% of the variation. The first two axes are plotted in Fig. 2. Samples from Thailand and Vietnam showed a higher amount of genetic variation than samples from Australia, which seemed more discrete. The Australian samples are clearly differentiated from the Vietnam and Thailand samples, whereas the Vietnam and Thailand samples also seem to be differentiated. STRUCTURE analysis, using the method of Evanno et al. (2005), also indicated that the number of populations within our data set was three (data not shown). However, in the STRUCTURE analysis, samples from Australia were a mixture of two populations, whereas samples from Vietnam and Thailand largely represented one population.

Fig. 2.

Factorial correspondence analysis by population for Ae. aegypti from Australia, Thailand, and Vietnam. Each point represents a sample region weighted by number of individuals and the sum of alleles present. Closed squares, Vietnam population samples; closed diamonds, Australian population samples; open circle, Thailand sample. Percentage of variation explained by the first factor = 32.36%.

Isolation by Distance

There was a significant correlation between genetic distance and geographic distance with the Mantel test showing a strong relationship between Slatkin's linearized FST and the natural log of geographic distance (Mantel r = 0.662, P < 0.001). Linear regression showed this relationship to be positive (Fig. 3a; R2 = 0.422, F = 123.462, P < 0.001). Within the Australian samples, there was also a positive correlation between genetic and geographic distance, although this relationship was somewhat weaker (Fig. 3b; Mantel r = 0.371, P = 0.026; R2 = 0.208, F = 16.806, P < 0.001).

Fig. 3.

Regression of Slatkin's linearized FST (FST/1 − FST) against the natural logarithm of geographical distance (km) for (a) all pairs of populations from Australia, Vietnam, and Thailand (Mantel r = 0.662, P < 0.001; R2 = 0.422, F = 123.462, P < 0.001); and (b) population pairs from Australia only (Mantel r = 0.371, P = 0.026; R2 = 0.208, F = 16.806, P < 0.001).

Effective Population Size and Migration Rate

We used two indirect methods to calculate the effective population size based on marker heterozygosity and mutation rate. The effective population size did not differ greatly between populations using these methods and was generally quite high (Table 3). If we assume a mutation rate of 6.3 × 10−6 (Schug et al. 1997), then Chillagoe in northern Queensland had the lowest population size estimate (IAM = 45051, SMM = 53229) and Thanh, Phu Dong, in southern Vietnam had the highest population estimate (IAM = 102077, SMM = 168672).

Estimates of Nm were generally low between populations with an overall estimate of 3.37 (95% CIs, 2.69–4.29). The lowest Nm was 1.65 and found between Machans Beach in Australia and Kim Bang, Ha Nam, in northern Vietnam. The highest Nm was 89.54 and found between Buon Me Thuat, Dak Lak, and Thanh Phu Dong, Ben Tre in Vietnam. Within Australia, values ranged between 1.99 (Chillagoe and Machans Beach) and 26.63 (Gordonvale and Mareeba), with an average Nm of 7.40.

Discussion

Screening with microsatellite and EPIC markers has identified that there is population structure within Ae. aegypti in Australia and in Vietnam. FST values among Australian populations vary significantly and an AMOVA indicates that significant variation (3.7%) exists between populations within regions. Linearized FST values (Slatkin 1995) also show isolation by geographic distance to some extent although this relationship is relatively weak. This weaker relationship is highlighted by some disjunct population structure in which widely spaced samples are not differentiated genetically (e.g., Townsville and Machans Beach, Townsville and Mossman, Tully and Mossman). This could reflect the translocation of mosquito eggs and aquatic stages in containers as a result of human travel throughout the region. Inland populations are, however, separated clearly from those on the coast (e.g., Chillagoe and Charters Towers). The FST values are consistent with those obtained by other researchers working with microsatellites and allozymes in Ae. aegypti (Paupy et al. 2004b, 2008).

Ae. aegypti shows greater allelic variation in Vietnam than in Australia and, although not significant, tends to have a higher number of alleles than the Thailand sample at each locus. Previous studies of Ae. aegypti in Vietnam showed lower levels of genetic differentiation in the wet season compared with the dry (Huber et al. 2002b). The collections from Vietnam analyzed in our study were all made during the wet season and few pairwise comparisons showed genetic differentiation. However, the samples of Huber et al. (2002b) were taken from Ho Chi Minh City and surrounding districts, whereas those of the current study were taken in north, south and central Vietnam so further comparisons cannot be made.

The AMOVA showed highly significant variation at the regional level, differentiating populations from Vietnam, Australia and Thailand. This variation is best shown by the correspondence analysis (Fig. 2), in which populations from each region seem separate. Therefore, it is likely that very limited movement occurs between these regions. Allelic richness was lower in Australia compared with Vietnam and possibly Thailand. Further samples would need to be taken from Thailand and other parts of Asia to confirm whether variation in allelic richness is lower in Australia, but the data suggest that Ae. aegypti may have gone through a bottleneck during colonization of Australia.

These data are consistent with observations of movement patterns of Ae. aegypti that suggest limited directional movement of 100 m within 8 d in Queensland (Russell et al. 2005). The domestic form of Ae. aegypti is closely associated with human habitation and, in Asia and the South Pacific, is not found in sylvan habitats (Failloux et al. 2002) because it may have difficulty crossing uninhabited areas (Maciel-De-Freitas et al. 2006). Ae. aegypti also has limited resistance to some climatic stresses that can further limit movement (Kearney et al. 2009).

The similar genetic constitution of disparate populations (like Mossman/ Townsville in Queensland and Ha Nam/Vinh Long in Vietnam) may be a consequence of human assisted movement. Recently, an incursion of Ae. aegypti occurred in isolated Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory and was attributed to human introduction. However, the presence of population genetic structure suggests that this form of movement is limited. Estimates of Nm between populations varied, but in most instances were low and indicated that generally only a small fraction of a local population consisted of migrants.

We also obtained some long-term indirect estimates of Ne from the microsatellite data. With a mutation rate of 6.3 × 10−6 (Schug et al. 1997), these varied from 45051 to 102077 for the infinite alleles model (Kimura and Crow 1964) and from 53229 to 168671 for the stepwise mutation model (Ohta and Kimura 1973). These estimates will generally have large confidence intervals and could be an order of magnitude greater, depending on the mutation rate. Here, we used the Drosophila microsatellite mutation rate (Schug et al. 1997), however, to obtain more accurate short-term estimates of Ne, temporal sampling spanning numerous field generations is required (Waples 1989).

The EPIC markers proved useful in detecting population genetic structure in Ae. aegypti. The markers were in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium suggesting that they reflect population processes rather than strong selection. The mean FST for these markers among populations was similar to that estimated for the microsatellites (0.073), although mean allele number was somewhat lower. The advantage of these markers is that they are unlikely to suffer from null alleles and can be isolated from genomic studies or expressed sequence tag libraries. EPIC markers are becoming more popular for use in population genetic studies in insects (Berrebi et al. 2006, Atarhouch et al. 2007, Rolland et al. 2007) and do not require assumptions about a particular model of evolution that is often required for microsatellites.

The data have several implications for novel control options when introducing mosquitoes into populations. Under several envisaged scenarios, new mosquito variants need to be established at a threshold exceeding an unstable equilibrium point (Turelli and Hoffmann 1999, Sinkins and Gould 2006, Huang et al. 2007). Once this point is exceeded, the new variants will spread close to fixation. For instance, in the mechanism involving Wolbachia, with nonoverlapping generations and no age structure, the unstable point for a Wolbachia variant is ≈20% depending on the rate of maternal transmission, fitness costs associated with the infection and incompatibility levels induced by Wolbachia (Turelli and Hoffmann 1999). Substantial numbers of new variants would be needed for this strategy to be successful, although there also might be other options such as decreasing numbers of the target population through pesticide applications, dry season targeting, or source reduction programs to remove desiccation resistant eggs, before establishing new variants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ben Wegener and Paul Mitrovski for technical assistance. This study was funded by a grant from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health through the Grand Challenges in Global Health Initiative and the Australian Research Council via the Special Research Centre program.

References Cited

- Atarhouch T, Rami M, Naciri M, Dakkak A. Genetic population structure of sardine (Sardina pilchardus) off Morocco detected with intron polymorphism (EPIC-PCR) Mar. Biol. 2007;150:521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Belkhir K, Borsa P, Chikhi L, Raufaste N, Bonhomme F. Laboratoire Génome, Populations, Interactions, CNRS UMR 5000. Université de Montpellier II; Montpellier, France: 2004. GENETIX 4.05, logiciel sous Windows TM pour la génétique des populations. [Google Scholar]

- Berrebi P, Retif X, Fang F, Zhang CG. Population structure and systematics of Opsariichthys bidens (Osteichthyes: Cyprinidae) in south-east China using a new nuclear marker: the introns (EPIC-PCR) Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2006;87:155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Bosio CF, Harrington LC, Jones JW, Sithiprasasna R, Norris DE, Scott TW. Genetic structure of Aedes aegypti populations in Thailand using mitochondrial DNA. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;72:434–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers EW, Meece JK, McGowan JA, Lovin DD, Hemme RR, Chadee DD, McAbee K, Brown SE, Knudson DL, Severson DW. Microsatellite isolation and linkage group identification in the yellow fever mosquito Aedes aegypti. J. Hered. 2007;98:202–210. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esm015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PE, Hugo LE, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Williams CR, Chenoweth SF, Ritchie SA, Ryan PA, Kay BH, Blows MW, O'Neill SL. The use of transcriptional profiles to predict adult mosquito age under field conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:18060–18065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604875103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DinardoMiranda LL, Contel EPB. Enzymatic variability in natural populations of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Brazil. J. Med. Entomol. 1996;33:726–733. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/33.5.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endersby NM, McKechnie SW, Vogel H, Gahan LJ, Baxter SW, Ridland PM, Weeks AR. Microsatellites isolated from diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (L.), for studies of dispersal in Australian populations. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2005;5:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Failloux A, Vazeille M, Rodhain F. Geographic genetic variation in populations of the dengue virus vector Aedes aegypti. J. Mol. Evol. 2002;55:653–663. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2360-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Failloux AB, Darius H, Pasteur N. Genetic differentiation of Aedes aegypti, the vector of dengue virus in French Polynesia. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 1995;11:457–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz AWE, Sanchez-Vargas I, Adelman ZN, Blair CD, Beaty BJ, James AA, Olson KE. Engineering RNA interference-based resistance to dengue virus type 2 in genetically modified Aedes aegypti. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:4198–4203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600479103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goudet J. FSTAT (version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. J. Hered. 1995;86:485–486. [Google Scholar]

- Hanna JN, Ritchie SA, Richards AR, Taylor CT, Pyke AT, Montgomery BL, Piispanen JP, Morgan AK, Humphreys JL. Multiple outbreaks of dengue serotype 2 in north Queensland, 2003/04. Aust. NZ J. Public Health. 2006;30:220–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2006.tb00861.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M, Haymer DS. Polymorphic intron sequences detected within and between populations of the oriental fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae) Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1997;90:825–831. [Google Scholar]

- Hood G, Hood G. PopTools computer program, version 2.5. Canberra, Australia: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Magori K, Lloyd AL, Gould F. Introducing transgenes into insect populations using combined gene-drive strategies: modeling and analysis. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2007;37:1054–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber K, Mousson L, Rodhain F, Failloux AB. Isolation and variability of polymorphic microsatellite loci in Aedes aegypti, the vector of dengue viruses. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2001;1:219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Huber K, Le Loan L, Hoang TH, Ravel S, Rodhain F, Failloux AB. Genetic differentiation of the dengue vector, Aedes aegypti (Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) using microsatellite markers. Mol. Ecol. 2002a;11:1629–1635. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01555.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber K, Le Loan L, Hoang TH, Tien TK, Rodhain F, Failloux AB. Temporal genetic variation in Aedes aegypti populations in Ho Chi Minh City (Vietnam) Heredity. 2002b;89:7–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber K, Le Loan L, Chantha N, Failloux AB. Human transportation influences Aedes aegypti gene flow in Southeast Asia. Acta Trop. 2004;90:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James AA. Gene drive systems in mosquitoes: rules of the road. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:64–67. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney M, Porter WP, Williams C, Ritchie S, Hoffmann AA. Integrating biophysical models and evolutionary theory to predict climatic impacts on species' ranges: the dengue mosquito Aedes aegypti in Australia. Funct. Ecol. 2009 (in press). (DOI: 10.1111/j.1365–2435.2008.01538.x) [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Crow JF. The number of alleles that can be maintained in a finite population. Genetics. 1964;49:725–738. doi: 10.1093/genetics/49.4.725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis P, Zaykin D. Genetic Data Analysis: computer program for the analysis of allelic data, version 1.0 (d16c) 2001 http://hydrodictyon.eeb.uconn.edu/people/plewis/software.php

- Maciel-De-Freitas R, Brocki R, Goncalves JM, Codeco CT, Lourenco-De-Oliveira R. Movement of dengue vectors between the human modified environment and urban forest in Rio de Janeiro. J. Med. Entomol. 2006;43:1112–1120. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)43[1112:modvbt]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill SA, Ramberg FB, Hagedorn HH. Phylogeography and population structure of Aedes aegypti in Arizona. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;72:304–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousson L, Vazeille M, Chawprom S, Prajakwong S, Rodhain F, Failloux AB. Genetic structure of Aedes aegypti populations in Chiang Mai (Thailand) and relation with dengue transmission. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2002;7:865–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun J, Bohonak AJ, Roderick GK. Population structure of the pumpkin fruit fly Bactrocera depressa (Tephritidae) in Korea and Japan: Pliocene allopatry or recent invasion? Mol. Ecol. 2003;12:2941–2951. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Gower AK. Surveys in northern Australia. Vol. 6. Health; NY: 1956. Control measures for Aedes aegypti; pp. 40–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T, Kimura M. Model of mutation appropriate to estimate number of electrophoretically detectable alleles in a finite population. Genet. Res. 1973;22:201–204. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300012994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashley DP, Rai KS. Comparison of allozyme and morphological relationships in some Aedes (Stegomyia) mosquitos (Diptera, Culicidae) Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1983;76:388–394. [Google Scholar]

- Paupy C, Chantha N, Vazeille M, Reynes JM, Rodhain F, Failloux AB. Variation over space and time of Aedes aegypti in Phnom Penh (Cambodia): genetic structure and oral susceptibility to a dengue virus. Genet. Res. 2003;82:171–182. doi: 10.1017/s0016672303006463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paupy C, Orsoni A, Mousson L, Huber K. Comparisons of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP), microsatellite, and isoenzyme markers: population genetics of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Phnom Penh (Cambodia) J. Med. Entomol. 2004a;41:664–671. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paupy C, Chantha N, Huber K, Lecoz N, Reynes JM, Rodhain F, Failloux AB. Influence of breeding sites features on genetic differentiation of Aedes aegypti populations analyzed on a local scale in Phnom Penh Municipality of Cambodia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004b;71:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paupy C, Brengues C, Kamgang B, Herve J-P, Fontenille D, Simard F. Gene flow between domestic and sylvan populations of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in North Cameroon. J. Med. Entomol. 2008;45:391–400. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[391:gfbdas]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravel S, Monteny N, Olmos DV, Verdugo JE, Cuny G. A preliminary study of the population genetics of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) from Mexico using microsatellite and AFLP markers. Acta Trop. 2001;78:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(01)00083-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond M, Rousset F. An exact test for population differentiation. Evolution. 1995;49:1280–1283. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb04456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter P. Oviposition, dispersal, and survival in Aedes aegypti: implications for the efficacy of control strategies. Vector-Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2007;7:261–273. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2006.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie SA, Long S, Smith G, Pyke A, Knox TB. Entomological investigations in a focus of dengue transmission in Cairns, Queensland, Australia, by using the sticky ovitraps. J. Med. Entomol. 2004;41:1–4. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-41.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland JL, Bonhomme F, Lagardere F, Hassan M, Guinand B. Population structure of the common sole (Solea solea) in the northeastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean sea: revisiting the divide with EPIC markers. Mar. Biol. 2007;151:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- Rousset F. Genetic differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics. 1997;145:1219–1228. doi: 10.1093/genetics/145.4.1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruang-areerate T, Kittayapong P. Wolbachia transinfection in Aedes aegypti: a potential gene driver of dengue vectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:12534–12539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508879103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell RC, Webb CE, Williams CR, Ritchie SA. Mark-release-recapture study to measure dispersal of the mosquito Aedes aegypti in Cairns, Queensland, Australia. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2005;19:451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2005.00589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider S, Roessli D, Excoffier L. ARLEQUIN, version 2.001: a software for population genetics and data analysis. Genetics and Biometry Laboratory, University of Geneva; Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. http://lgb.unige.ch/arlequin/ [Google Scholar]

- Schug MD, Mackay TF, Aquadro CF. Low mutation rates of microsatellite loci in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:99–102. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair DP. The distribution of Aedes aegypti in Queensland, 1990 to 30 June 1992. Commun. Dis. Intell. 1992;16:400–403. [Google Scholar]

- Sinkins SP, Gould F. Gene drive systems for insect disease vectors. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:427–435. doi: 10.1038/nrg1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M. A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics. 1995;139:457–462. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slatkin M, Barton NH. A comparison of 3 indirect methods for estimating average levels of gene flow. Evolution. 1989;43:1349–1368. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb02587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slotman MA, Kelly NB, Harrington LC, Kitthawee S, Jones JW, Scott TW, Caccone A, Powell JR. Polymorphic microsatellite markers for studies of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae), the vector of dengue and yellow fever. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2007;7:168–171. [Google Scholar]

- Turelli M, Hoffmann AA. Microbe-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility as a mechanism for introducing transgenes into arthropod populations. Insect Mol. Biol. 1999;8:243–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.820243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waples RS. A generalized approach for estimating effective population size from temporal changes in allele frequency. Genetics. 1989;121:379–391. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.2.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts DM, Burke DS, Harrison BA, Whitmire RE, Nisalak A. Effect of temperature on the vector efficiency of Aedes aegypti for dengue-2 virus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1987;36:143–152. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1987.36.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks AR, McKechnie SW, Hoffmann AA. Dissecting adaptive clinal variation: markers, inversions and size/stress associations in Drosophila melanogaster from a central field population. Ecol. Lett. 2002;5:756–763. [Google Scholar]

- Weir B, Cockerham C. Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution. 1984;38:1358–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1984.tb05657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CR, Long SA, Russell RC, Ritchie SA. Field efficacy of the BG-Sentinel compared with CDC Backpack Aspirators and CO2-baited EVS traps for collection of adult Aedes aegypti in Cairns, Queensland, Australia. J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2006;22:296–300. doi: 10.2987/8756-971X(2006)22[296:FEOTBC]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZY, Khoo CCH, Dobson SL. Science. Vol. 310. Wash., D.C.: 2005. Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population; pp. 326–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZY, Khoo CCH, Dobson SL. Interspecific transfer of Wolbachia into the mosquito disease vector Aedes albopictus. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2006;273:1317–1322. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakob L, Alphey L, Bonsall MB. Aedes aegypti control: the concomitant role of competition, space and transgenic technologies. J. Appl. Ecol. 2008;45:1258–1265. [Google Scholar]