Abstract

Biomechanical forces are emerging as critical regulators of embryogenesis, particularly in the developing cardiovascular system1,2. After initiation of the heartbeat in vertebrates, cells lining the ventral aspect of the dorsal aorta, the placental vessels, and the umbilical and vitelline arteries initiate expression of the transcription factor Runx1 (refs 3–5), a master regulator of haematopoiesis, and give rise to haematopoietic cells4. It remains unknown whether the biomechanical forces imposed on the vascular wall at this developmental stage act as a determinant of haematopoietic potential6. Here, using mouse embryonic stem cells differentiated in vitro, we show that fluid shear stress increases the expression of Runx1 in CD41+c-Kit+ haematopoietic progenitor cells7,concomitantly augmenting their haematopoietic colony-forming potential. Moreover, we find that shear stress increases haematopoietic colony-forming potential and expression of haematopoietic markers in the paraaortic splanchnopleura/aorta–gonads–mesonephros of mouse embryos and that abrogation of nitric oxide, a mediator of shear-stress-induced signalling8, compromises haematopoietic potential in vitro and in vivo. Collectively, these data reveal a critical role for biomechanical forces in haematopoietic development.

In the mouse, the first haemogenic areas appear in the yolk sac starting at day 7.5 of development (E7.5)9. After the establishment of circulation and the onset of vascular flow at day 8.5, additional haemogenic sites appear between day 9 and 10.5 as Runx1+ regions within the developing vasculature10. Given the developmental and anatomical relationship of haematopoietic precursors with the mechano-responsive vascular endothelium11,12, together with the temporal correlation between the establishment of circulation and the appearance and expansion of vascular haemogenic sites, we proposed that biomechanical forces might act to promote haematopoiesis.

To explore this hypothesis, we differentiated mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells as embryoid bodies, a system that recapitulates the early stages of embryonic haematopoietic development. In embryoid bodies, cells first commit to mesoderm and then produce Flk1+ cells containing the earliest embryonic haematopoietic precursors13. Embryoid bodies were cultured until the appearance of Flk1+ mesoderm on day 3.25 of differentiation13,14, disaggregated and plated on flat gelatinized surfaces. To define the type of biomechanical stimulation to apply to these cultured cells, we focused on the haemodynamic environment present in the aorta–gonad–mesonephros (AGM) region, the best characterized haemogenic site at the onset of circulation15,16. The pulsatile characteristics of flow in the aorta generate a complex interplay of distinct types of biomechanical forces including circumferential stress, hydrodynamic pressure and shear stress. Of these forces, we focused on fluid shear stress, the frictional force generated by viscous flow acting along cells lining blood vessels, because it has been shown to exert profound effects on the structure and function of vascular endothelial cells12. We therefore chose to stimulate cultured cells using a wall shear stress (WSS) comparable to that acting along the dorsal aorta throughout the cardiac cycle at E10.5. To estimate the time-average of this value, we used previously published ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) data for the time-average velocity over one cardiac cycle (velocity time integral, 4.74 mm, divided by the cycle length, 350 ms, and the earliest available values for dorsal aorta diameter, 0.33 mm (refs 10, 17)). Calculating the circular Poiseuille flow solution for wall shear stress with these values yielded a dorsal aorta WSS at E10.5 of approximately 5 dyn cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). This approach assumed that the UBM velocity data represented mean blood flow and that Poiseuille flow assumptions are valid within the E10.5 dorsal aorta18 (see Methods).

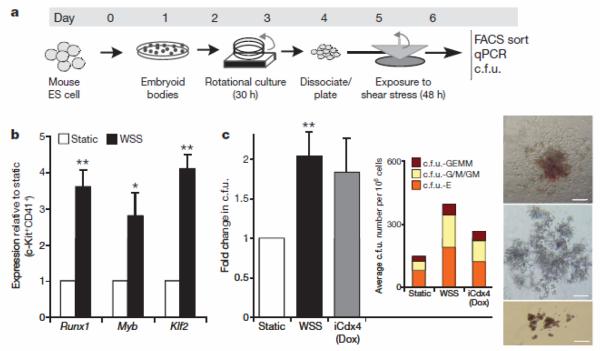

Embryoid-body-derived cells were exposed to this biomechanical stimulus (WSS) or cultured under static conditions for 48 h (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Exposure of embryoid-body-derived cells to shear stress caused an increase in cells positive for CD31 (PECAM1), a marker of endothelial19 and haematopoietic lineages (Supplementary Fig. 1c). CD41+c-Kit+ haematopoietic precursors7 were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Gene expression analysis within this compartment demonstrated a strong shear-stress-mediated upregulation of the transcription factors Runx1 (also called Cbfa2; 4.6-fold) and Myb (2.8-fold), the prototypical markers of haemogenic sites4, and of Klf2 (4.1-fold), a gene previously shown to be a driver of erythropoiesis20 and to be mechano-activated in endothelial cells21 (Fig. 1b). Runx1 upregulation was observed in the unsorted cell population and this effect was specific to the WSS values estimated for the AGM region in the early embryo. Indeed, when the embryoid-body-derived cells were exposed to a shear stress of different magnitude or to a shear stress waveform characteristic of the human aorta the expression of Runx1 was not increased (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

Figure 1. Shear stress induces haematopoietic commitment from ES-derived cells.

a, Experimental protocol used to induce haematopoietic differentiation from ES-derived cells in the presence of wall shear stress (WSS). ES cells are differentiated with the embryoid body method for 3.25 days, disaggregated and plated on gelatinized surfaces. Cell monolayers were exposed to shear stress and then collected on day 6 for further analysis b, Real-time Taqman PCR-based gene expression analysis in FACS-sorted CD41+c-Kit+ embryoid-body-derived haematopoietic precursors. Exposure to WSS induces upregulation of the haematopoietic markers Runx1 (P=0.01), Myb (P=0.03) and Klf2 (P=0.001), n=3. c, Methylcellulose haematopoietic c.f.u. assay. WSS increases the frequency of haematopoietic progenitors in complete M3434 methylcellulose. n=4, analysis of variance (ANOVA) P=0.01. Dox, doxycycline. Inset shows average distribution of haematopoietic colony types. c.f.u.-GEMM, c.f.u. granulocyte-erythroid-myeloid-megakaryocytes; c.f.u.-G/M/GM, c.f.u. granulocytes/macrophages/granulocyte-macrophages; c.f.u.-E, c.f.u. erythroid. Bar graphs represent average±s.e.m. Pictures show representative colonies: c.f.u.-GEMM (top), c.f.u.-G/M/GM (middle), c.f.u.-E (bottom). Scale bar, 200 μmm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01.

Next, we interrogated the functional significance of these gene expression changes using haematopoietic colony-forming assays. As a positive control, we used the iCdx4 ES cell line, which carries a doxycycline-inducible Cdx4 transgene that enhances differentiation to haematopoietic precursors22. Shear stress increased the frequency of haematopoietic colony-forming units (c.f.u.) when compared to static (no shear stress) conditions, with a magnitude comparable to that obtained by induction of Cdx4 with doxycycline (Fig. 1c). Notably, the Cdx4 transgene was not activated in cells exposed to shear stress (Supplementary Fig. 1e). We observed similar results when we analysed Flk1+ cells enriched by magnetic cell sorting, indicating that the shear stress response occurs in the Flk1+ mesoderm (Supplementary Fig. 1f). Importantly, the small number of detached cells in static or shear conditions was very similar (<0.5%) and the haematopoietic potential in this non-adherent fraction was higher in the cells exposed to WSS (Supplementary Fig. 1g). These observations demonstrate that biomechanical forces enhance embryonic stem-cell-derived haematopoiesis.

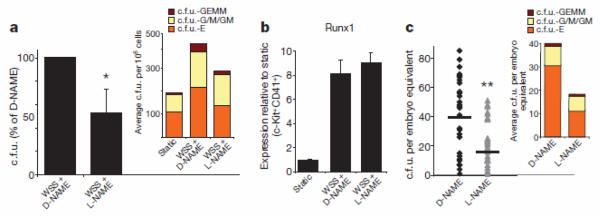

To gain mechanistic insights into this process, we investigated the role of nitric oxide (NO), a well characterized signalling pathway strongly regulated by shear stress8, and a known modulator of haematopoiesis23. Inhibition of NO production via the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)24 resulted in a significant reduction of the shear-stress-induced enrichment in c.f.u. as compared with cells treated with the inactive stereoisomer D-NAME (Fig. 2a). Notably, L-NAME did not affect shear-stress-induced Runx1 upregulation in CD41+c-Kit+ cells, indicating that shear-stress-mediated Runx1 upregulation is upstream of NO production (Fig. 2b). L-NAME and D-NAME had no effect on c.f.u. formation or Runx1 expression in cells grown under static conditions (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b).

Figure 2. Nitric oxide production regulates the expansion of haematopoietic progenitors.

a, Methylcellulose haematopoietic c.f.u. assay. Pharmacological inhibition of nitric oxide synthesis with L-NAME reduces by 50% the WSS-mediated increase in haematopoietic c.f.u.; n=3, P=0.04. Inset shows the average distribution of colony types. b, L-NAME does not affect WSS-mediated Runx1 upregulation; n=3. c, In vivo c.f.u. assay. Exposure of developing embryos to L-NAME from E8.5 to E10.5 leads to a reduction in haematopoietic progenitors in the AGM region. D-NAME, n=30; L-NAME, n=32; P=0.0008. Inset shows average distribution of colonies per AGM. Bar graphs represent average±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.005.

We next sought to determine the role of NO production on intraembryonic haematopoiesis in vivo. We administered L-NAME or D-NAME to pregnant mice for 48 h, starting from the time of establishment of circulation (E8.5), and assessed the number of c.f.u. in the AGM regions of E10.5 embryos. As shown in Fig. 2c, systemic inhibition of NO production led to a marked decrease in the number of c.f.u. per AGM. In this in vivo setting, we cannot distinguish between the direct effect of NO inhibition on haematopoietic precursors and the alterations of embryonic haemodynamics that result from changes in vascular tone triggered by the systemic inhibition of NO synthases24. However, our in vitro data document that NO production is required for the shear-stress-mediated stimulation of haematopoietic progenitors, thereby establishing that the NO pathway is an important mediator of the effect of shear stressin haematopoiesis.

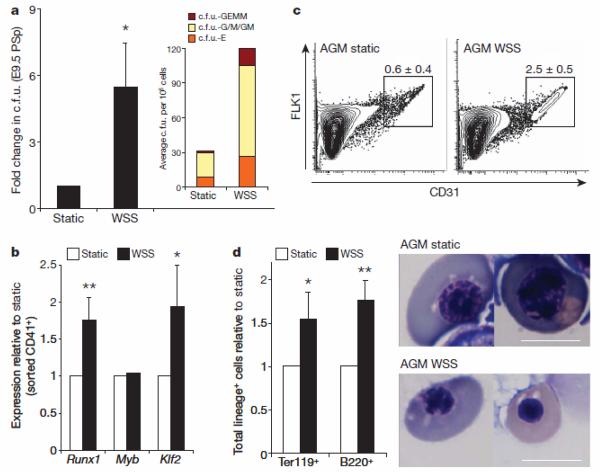

To examine the effect of fluid shear stress on the haematopoietic forming potential of embryonic haematopoietic sites, we established two-dimensional primary cultures of para-aortic splanchnopleura (PSp, the precursor of the AGM in E9–E9.5 embryos) or AGM-derived cells. When PSp regions from E9.5 murine embryos were disaggregated, plated and exposed to shear stress, we observed an increase in c.f.u. when compared to static controls (Fig. 3a). Likewise, when we exposed cells isolated from the AGM regions of E10.5 murine embryos to shear stress, we observed enhanced expression of Runx1 and Klf2, but for unclear reasons not Myb, in CD41+ haematopoietic progenitors enriched by FACS (Fig. 3b)25. Shear stress also induced upregulation of CD31+ cells (Fig. 3c). We then examined the effect of shear stress on specific haematopoietic lineages by flow cytometry, and documented an increase in cells positive for the B lymphocyte marker B220, and Ter119, a marker of erythroblasts (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Furthermore, the erythroblasts present in the shear-stress-treated cultures displayed morphological features consistent with later stages of erythroid maturation (that is, pycnotic erythroblasts and a haemoglobinized red pellet versus earlier polychromatic erythro-blasts present in the static control; Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 3b), suggesting accelerated erythroid differentiation in response to shear stress. This was associated with strong upregulation of Klf2, a known driver of erythropoiesis. Taken together, these observations show that shear stress increases both the prevalence of haematopoietic progenitors and the expression of haematopoietic markers in primary cultures of cells taken from the PSp/AGM, indicating that shear stress acts to enhance embryonic haematopoiesis.

Figure 3. Shear stress induces haematopoiesis in PSp/AGM-embryo-derived cells.

a, Methylcellulose haematopoietic c.f.u. assay. WSS increases the frequency of haematopoietic progenitors in two-dimensional primary PSp cultures from E9.5 embryos; n = 4(P = 0.038); bar graphs represent average ± s.e.m. Inset shows average distribution of haematopoietic colony types. b, WSS induces upregulation of the haematopoietic markers Runx1 (P = 0.01) and Klf2 (P = 0.05) in FACS-sorted AGM-derived CD41+ haematopoietic progenitors as documented by real-time PCR; n = 3, bar graphs represent average ± s.e.m. c, FACS analysis. WSS induces an increase in CD31+ cells in two-dimensional primary AGM cultures; P = 0.005, n = 3, average ± s.d. d, WSS modulates the differentiation of AGM-derived haematopoietic progenitors as shown by an increase in absolute number of cells positive for the erythroid marker Ter119 (P = 0.02) and for the lymphoid marker B220 (P = 0.01); n = 3, bar graphs represent average ± s.e.m. Shear stress induces maturation of erythroid precursors as documented by cell morphology in cytospins, which show pycnotic erythroblasts in WSS-treated samples, and polychromatic erythroblasts in static cultures. Scale bar, 10 μm. *P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

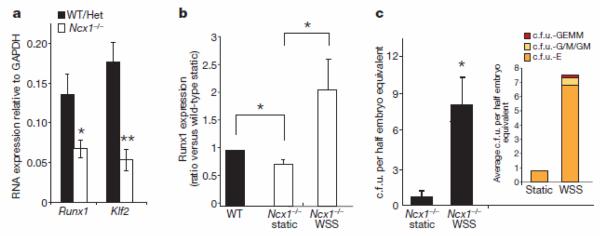

To evaluate further the relevance of shear stress in the maturation of embryonic haemogenic sites in vivo, we assessed the effect of fluid shear stress in mouse embryos carrying a homozygous mutation in the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger Ncx1 (also called Slc8a1). These embryos fail to initiate the heartbeat and therefore lack circulation26. Ncx1−/− embryos are deficient in haematopoietic c.f.u. in the PSp, possibly due to a failure of redistribution from the yolk sac27, and have a 6-fold reduction in CD41+ haematopoietic progenitors in the placental vasculature5. The data presented here suggest that the haematopoietic deficiencies observed in Ncx1−/− embryos may be due, at least in part, to a lack of biomechanical stimulation at haemogenic vascular sites. To evaluate this possibility, we determined the levels of Runx1 and Klf2 expression in the PSp/AGM region of E9.25 Ncx1−/− embryos and wild-type littermates. As shown in Fig. 4a, both Runx1 and Klf2 were expressed in Ncx1−/− PSp/AGM region at significantly lower levels than in controls, whereas expression of the endothelial-specific marker VE-cadherin was similar in the two groups, suggesting that the content of vascular endothelial tissue was similar in both samples (data not shown). Importantly, at this developmental stage, Runx1 is exclusively expressed in haemogenic sites within the embryo trunk28,29. We then examined if exposure to biomechanical stimulation per se could restore expression of Runx1 and haematopoietic colony-forming potential in Ncx1−/− embryo-derived cells. We isolated cells from the PSp/AGM region of Ncx1−/− embryos, and either maintained them under static conditions or exposed them to shear stress. As shown in Fig. 4, shear stress induced Runx1 expression (Fig. 4b) and c.f.u. activity (Fig. 4c) in cells from Ncx1−/− embryos. These data demonstrate that shear stress is capable of upregulating expression of the haematopoietic master regulator Runx1 and promoting haematopoietic colony-forming activity in cells derived from the PSp region of Ncx1−/− embryos, and indicates that the haematopoietic deficiency of Ncx1−/− embryos is not a cell-autonomous defect but rather a consequence of alterations in haemodynamics affecting vascular haemogenic sites.

Figure 4. Runx1 expression and c.f.u. activity are shear-stress-dependent.

a, PSp isolated from E9.25 Ncx1−/− embryos show reduced gene expression levels of the haematopoietic markers Runx1 (P = 0.02) and Klf2 (P = 0.003) when compared to matched wild-type (WT) or heterozygous (Het) littermate controls; n = 13 Ncx1−/−, n = 15 controls. b, Shear stress increases the expression of Runx1 in E9.25 Ncx1−/− PSp cultures to levels comparable to the one observed in littermate controls; real-time quantitative PCR, n = 4, ANOVA, P = 0.03. Post-hoc multiple comparisons are two-tailed t-test with P < 0.02. c, Shear stress induces c.f.u. activity in Ncx1−/− PSp-derived cells. Average ± s.e.m.; P = 0.01. Inset shows average distribution of haematopoietic colony types at day 14 after replating; n = 6. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.005.

Our results demonstrate that biomechanical forces stimulate embryonic haematopoiesis both in ES cell cultures and within murine embryos. These data establish a link between the initiation of the heartbeat, vascular flow and embryonic haematopoietic development, and provide new perspectives for the manipulation and production of haematopoietic progenitors from pluripotent stem cells in vitro, a key process for the implementation of stem-cell-based therapy of haematological diseases.

METHODS SUMMARY

Haemodynamic shear stress in the embryonic aorta was estimated using previously published fluid dynamic data from the developing mouse embryo10,17,30 and assuming circular Poiseuille flow. Ainv15 CDX4-inducible mouse embryonic stem cells (iCDX4 ES) were cultured as described22 and differentiated via the hanging-drop embryoid body method. Differentiated ES cells were plated at 100,000 per cm2 on 95 cm2 plates, and exposed to shear stress in the presence or absence of 2 mM N(G)-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) or 2 mM N(G)-nitro-D-arginine methyl ester (D-NAME). Pregnant Swiss–Webster mice were purchased from Taconic farms. Noon on the day the copulation plug was found was designated 0.5 days of gestation (E0.5). PSp/AGM regions were dissected with a conservative approach, preserving the somites. Two-dimensional primary PSp/AGM cultures were optimized in the absence or presence of growth factors (ECGS, heparin, SCF, VEGF, TPO and Flt3 ligand).

METHODS

Mouse ES cell culture and differentiation

Ainv15 CDX4-inducible mouse embryonic stem cells (iCDX4 ES) were cultured on mitomycin-treated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Chemicon, strain CF-1) and passaged every 2–3 days with 0.25% trypsin/EDTA as previously described22. To induce differentiation, ES cells were trypsinized, gently dispersed by repetitive pipetting and replated for 45 min at 37 °C for MEF depletion. Floating and loosely adherent cells were gathered, checked for viability with trypan blue, and diluted in embryoid body differentiation media (IMDM, 10% FCS Stem Cell technologies catalogue number 06952, 10 units ml−1 penicillin, 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 1 mM l-glutamine, 3.8 nl ml−1 monothioglycerol, 0.2 mg ml−1 Fe-saturated transfer-rin, 0.5 mg ml−1 ascorbic acid) to a final concentration of 6.7 × 103 cell ml−1. Embryoid bodies were cultured via the hanging-drop method in 15-μl drops on 15 cm bacterial dishes. Typically 100 15-cm plates of embryoid bodies were used per experiment. After 48 h, embryoid bodies were pooled into calcium- and magnesium-containing warm PBS and collected by sedimentation in 50-ml Falcon tubes. Pooled embryoid bodies were transferred to 10-cm tissue culture dishes containing 10 ml of embryoid body differentiation media each, placed on an orbital shaker moving at 75 r.p.m., and incubated for an additional 30 h. After this second culture phase, day 3.25 embryoid bodies were collected by precipitation, washed two times in 30-ml calcium-free PBS and trypsinized for 1 min in a 1:1 dilution of calcium-free PBS and 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA. Trypsinization was blocked by addition of 10 ml embryoid body differentiation media.

Haemodynamic shear-stress estimation

Wall shear stress acting along the dorsal aorta transiently increases during embryonic development once the heart begins beating. This increase in shear stress may be attributed to both an increase in blood flow velocity, a result of increasing cardiac output31,32, and an increase in viscosity, an effect of increasing haematocrit33. However, during the first two embryonic days after the initiation of a beating heart (E8–E10), the haematocrit rises, but remains below 20%. This change has an insignificant contribution to blood viscosity34 and, therefore, at these early time points blood viscosity can be assumed constant and equal to 0.015 dyn s−1 cm−2. Using ultrasound biomicroscopy (UBM) data, one study32 has previously determined blood flow in the developing embryo dorsal aorta to be laminar throughout the cardiac cycle with minimal skewing of the spatial velocity profile, as determined by calculation of non-dimensional fluid dynamic parameters at E11.5, including the Reynolds number (157), Womersley parameter (0.63) and Dean number (39), respectively. Assuming such fluid dynamic parameters remain valid for earlier time points during development, as well as that the instantaneous blood velocity profile is parabolic, we estimated the dorsal aorta wall shear stress based on circular Poiseuille flow in which the wall shear stress, τ, is calculated by τ = 8μV/D, where μ is the apparent viscosity (dyn s−1 cm−2), V (mm s−1) is the time-average mean blood flow velocity, and D (mm) is the vessel diameter. A similar strategy33 has been used to estimate embryonic shear stress levels in the developing embryo (E8.5–10.5).

Mouse ES cell exposure to shear stress

Differentiated ES cells were plated at 100,000 per cm2 on horizontal 95-cm2 plates, compatible with a Dynamic Flow System35. The plates were coated with a thick layer of 1% gelatin (DIFCO 214340, Becton Dickinson). After 12 h, cells were washed three times with 10 ml of warm PBS with calcium and incubated for 45 min with embryoid body differentiation media with or without 2 mM N(G)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) or 2 mM N(G)-nitro-d-arginine methyl ester (D-NAME) (Sigma-Aldrich). Following 45 min of incubation time, cells were either moved to the Dynamic Flow System and exposed to shear stress or maintained in a standard cell culture incubator. The shear stress ramped in a step-wise fashion from 0 to 5 dyn cm−2 over a period of 10 h. Following the 10-h ramping period, the cells were then exposed to a constant 5 dyn cm−2 shear stress for 38 h. In cells exposed to shear stress, culture media with or without D-NAME or L-NAME was automatically exchanged and stored at 37 °C and 5% CO2. In static controls, culture media was replaced after 24 h and stored in 75-cm2 flasks in a cell culture incubator. After 48 h exposure to shear stress or growth under static conditions, cells were detached by 10 min incubation with a 1:1 dilution of Trypsin–Versene mixture (Cambrex, number 17-161E) and Hank's Balanced Salt Solution.

Primary AGM/PSp culture

E9.25/9.5 or E10.5 murine embryos were collected in PBS, and a conservative dissection of the AGM/PSp region preserving the somites was performed. Typically, 32 embryos were used per condition on either the full Dynamic Flow System cell growth surface area (95 cm2, E10.5 embryos) or about one-third of the Dynamic Flow System cell growth surface area (38 cm2, E9.5). For the Ncx1−/− rescue experiment, single E9.25 PSp were disaggregated independently, divided in two and plated at a density of half embryo equivalent per 0.3 cm2 either in the Dynamic Flow System or in a 96-well format system. E9.5/E9.25 embryos were dissected within a maximum of 2.5 h and exposed to dispase (see below for details) without any delay. PSp-derived cells were plated in M5300 Myelocult medium (Stem Cell technologies) in the absence of hydrocortisone on surfaces coated for 1 h with a 1:20 matrigel dilution (Beckton Dickinson), cells adhered for 6.5 h and were then moved to the shear stress culture system for 36 h in either static condition or exposed to shear stress. When culturing cells in 96-well format, Myelocult was enriched with 25 ml l−1 of 1 M HEPES (Invitrogen). The shear stress ramped in a step-wise fashion from 0 to 5 dyn cm−2 over a period of 10 h. After the 10-h ramping period, as described in Supplementary Fig. 1a, the cells were exposed to a constant 5 dyn cm−2 shear stress for 26 h. Cells were harvested by dissociation with 0.1% dispase for 20 min. E10.5 AGM regions were dissociated in dispase in the same manner. E10.5 AGM-derived cells were plated overnight on 1% gelatin-coated surfaces in IMDM 10% FCS, 1× NEAA (Gibco), 1× β-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), 1 mM l-glutamine, 10 units ml−1 penicillin, 10 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 50 μg ml−1 ECGS, 100 μg ml−1 heparin, 100 ng ml−1 SCF, 40 ng ml−1 VEGF, 40 ng ml−1 TPO and 100 ng ml−1 Flt3 ligand overnight. IMDM media supplementation was then reduced to 25 μg ml−1 ECGS, 50 μg ml−1 heparin, 25 ng ml−1 SCF, 20 ng ml−1 VEGF, 10 ng ml−1 TPO and 25 ng ml−1 Flt3 ligand when cells were moved to the Dynamic Flow System and kept for 48 h in either static condition or exposed to shear stress. The shear stress ramped in a step-wise fashion from 0 to 5 dyn cm−2 over a period of 10 h. After the 10-h ramping period, the cells were then exposed to a constant 5 dyn cm−2 shear stress for 38 h. Cells were harvested as described herein for mouse ES-derived cells. Non-adherent cells were gathered by centrifugation. Embryos derived from Ncx1+/− mothers were identified as mutant (Ncx1−/−) or heterozygous/wild type by visual inspection of the yolk sac vasculature. Genotype was further confirmed by automated genotyping (Transnetyx) on embryonic biopsies collected at the time of dissection. Dispase stock solution was prepared diluting the commercially available powder form (GIBCO) into PBS without calcium or magnesium to a final concentration of 2.5 g per 100 ml. The solution was filtered in 0.22 μM tissue culture filters and stored at −20 °C. The stock was diluted 1:20 in PBS with calcium and magnesium to make working solutions. Embryonic tissue was disaggregated by incubating it in dispase working solution for 40 min in a thermal mixer rotating a 1,100 r.p.m. at 37 °C. After the first 20 min of incubation, dispase solution was pipetted up and down about 15 times to break larger tissue pieces. To detach cells plated on matrigel, cells were covered in dispase working solution, incubated 20 min in a 37 °C incubator and then collected by pipetting. Before removing dispase, cells were incubated for another 20 min in a 37 °C water bath.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted with the QIAGEN RNAeasy Micro Kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions. For RNA extraction from CD41+ c-Kit+ cells, approximately 7,000 cells were sorted directly into 300 μl of lysis buffer. Reverse transcription of RNA was performed using Applied Biosystems Multiscribe DNA polymerase, according to the manufacturer's instructions. When processing FACS-sorted cells, RNA was eluted in 20 μl and all collected RNA was used in 50 μl reverse transcription reactions. Real-time Taqman PCR (Applied Biosystems) was performed in 20 μl reactions with primers provided by Applied Biosystems, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

FACS sorting and analysis

Cells were incubated with Fc Block antibody (BD 553141, dilution 1:100) and then stained with anti-CD41 antibody (BD 553848, 1:150 dilution), anti-c-Kit antibody (BD 553356, 1:150 dilution), anti-Flk1 antibody (BD 555308, 1:150 dilution), anti-CD31 antibody (BD 553372, 1:150 dilution) and 7AAD (BD 559925, 1:75 dilution) and sorted with a FACS-Aria system (BD Biosciences).

Methylcellulose c.f.u. assay

Methylcellulose assay was performed as previously described36 in M3434 complete methylcellulose (Stem Cell Technologies) and scored on day 8–10 after plating. When assessing c.f.u. activity on cells exposed to shear stress in 96-well format (Ncx1−/− PSp-derived cells), at the end of the experiment shear stress media was exchanged with 100 μl of M3434 complete methylcellulose medium. Cells were allowed to grow in M3434 in the 96-well plate for 4 days and then replated in 2 ml of complete M3434 media in optical quality 35-mm dishes. To replate, 100 ml of IMDM 15% FCS was added to the wells and cells were collected by repeated pipetting before washing the well with additional 100 μl of IMDM 15% FCS. Plates were scored on day 14 after replating.

Blockade of NO production in vivo

Day 7 post coitum timed-pregnant Swiss–Webster mice were purchased from Taconic Farms. Noon on the day the copulation plug was found was designated 0.5 days. On day E8.5 (day 9 post coitum) mice were intraperitoneally injected with 300 mg kg−1 of L-NAME or D-NAME (Sigma) dissolved in sterile, apyrogenic saline solution using a dose volume of 10 ml kg−1 (ref. 37). The injection was repeated after 24 h. Exactly 24 h after the second injection, mice were killed with CO2, embryos were harvested, and a conservative dissection of the AGM was performed. Embryo trunks were dissociated with 0.1% dispase and analysed with the methylcellulose assay. Experiments were carried out with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval from Harvard Medical School or Children's Hospital, Boston.

Statistical analysis

All the statistical analyses were performed using un-paired two-tailed Student's t-test assuming experimental samples of equal variance, unless otherwise specified.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Losyev for assistance with flow cytometry, S. Schmitt for critical help in optimizing AGM culture conditions, C. Lengerke and Y. Mukouyama for critical discussions. L.A. was partially funded by the Giovanni Armenise-Harvard Foundation. O.N. was partially funded by the Barrie de la Maza Foundation. G.G.-C. was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and G.Q.D was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Director's Pioneer Award of the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. G.Q.D. is a recipient of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research and is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Hove JR, et al. Intracardiac fluid forces are an essential epigenetic factor for embryonic cardiogenesis. Nature. 2003;421:172–177. doi: 10.1038/nature01282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lucitti JL, et al. Vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac requires hemodynamic force. Development. 2007;134:3317–3326. doi: 10.1242/dev.02883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Porrero JA, Godin IE, Dieterlen-Lievre F. Potential intraembryonic hemogenic sites at pre-liver stages in the mouse. Anat. Embryol. 1995;192:425–435. doi: 10.1007/BF00240375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.North TE, et al. Runx1 expression marks long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells in the midgestation mouse embryo. Immunity. 2002;16:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00296-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhodes KE, et al. The emergence of hematopoietic stem cells is initiated in the placental vasculature in the absence of circulation. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:252–263. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lensch MW, Daley GQ. Origins of mammalian hematopoiesis: in vivo paradigms and in vitro models. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 2004;60:127–196. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)60005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mikkola HK, Fujiwara Y, Schlaeger TM, Traver D, Orkin SH. Expression of CD41 marks the initiation of definitive hematopoiesis in the mouse embryo. Blood. 2003;101:508–516. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garcia-Cardena G, et al. Dynamic activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase by Hsp90. Nature. 1998;392:821–824. doi: 10.1038/33934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haar JL, Ackerman GA. A phase and electron microscopic study of vasculogenesis and erythropoiesis in the yolk sac of the mouse. Anat. Rec. 1971;170:199–223. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ji RP, et al. Onset of cardiac function during early mouse embryogenesis coincides with entry of primitive erythroblasts into the embryo proper. Circ. Res. 2003;92:133–135. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000056532.18710.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tavian M, et al. The vascular wall as a source of stem cells. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2005;1044:41–50. doi: 10.1196/annals.1349.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garin G, Berk BC. Flow-mediated signaling modulates endothelial cell phenotype. Endothelium. 2006;13:375–384. doi: 10.1080/10623320601061599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kabrun N, et al. Flk-1 expression defines a population of early embryonic hematopoietic precursors. Development. 1997;124:2039–2048. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.10.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lengerke C, et al. BMP and WNT specify hematopoietic fate by activation of the CDX-Hox pathway. Cell Stem Cell. 2008;2:72–82. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Medvinsky A, Dzierzak E. Definitive hematopoiesis is autonomously initiated by the AGM region. Cell. 1996;86:897–906. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cumano A, Dieterlen-Lievre F, Godin I. Lymphoid potential, probed before circulation in mouse, is restricted to caudal intraembryonic splanchnopleura. Cell. 1996;86:907–916. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phoon CK, Aristizabal O, Turnbull DH. Spatial velocity profile in mouse embryonic aorta and Doppler-derived volumetric flow: a preliminary model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283:H908–H916. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00869.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ku D. Blood flow in arteries. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 1997;29:399–434. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamamoto K, et al. Fluid shear stress induces differentiation of Flk-1-positive embryonic stem cells into vascular endothelial cells in vitro. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2005;288:H1915–H1924. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00956.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basu P, et al. KLF2 is essential for primitive erythropoiesis and regulates the human and murine embryonic beta-like globin genes in vivo. Blood. 2005;106:2566–2571. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parmar KM, et al. Integration of flow-dependent endothelial phenotypes by Kruppel-like factor 2. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:49–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI24787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Y, Yates F, Naveiras O, Ernst P, Daley GQ. Embryonic stem cell-derived hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:19081–19086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506127102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aicher A, et al. Essential role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase for mobilization of stem and progenitor cells. Nature Med. 2003;9:1370–1376. doi: 10.1038/nm948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rees DD, Palmer RM, Moncada S. Role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in the regulation of blood pressure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1989;86:3375–3378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.9.3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferkowicz MJ, et al. CD41 expression defines the onset of primitive and definitive hematopoiesis in the murine embryo. Development. 2003;130:4393–4403. doi: 10.1242/dev.00632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koushik SV, et al. Targeted inactivation of the sodium-calcium exchanger (Ncx1) results in the lack of a heartbeat and abnormal myofibrillar organization. FASEB J. 2001;15:1209–1211. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0696fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lux CT, et al. All primitive and definitive hematopoietic progenitor cells emerging prior to E10 in the mouse embryo are products of the yolk sac. Blood. 2007;111:3435–3438. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-107086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simeone A, Daga A, Calabi F. Expression of runt in the mouse embryo. Dev. Dyn. 1995;203:61–70. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.North T, et al. Cbfa2 is required for the formation of intra-aortic hematopoietic clusters. Development. 1999;126:2563–2575. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jones EA, Baron MH, Fraser SE, Dickinson ME. Measuring hemodynamic changes during mammalian development. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H1561–H1569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00081.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ji RP, et al. Onset of cardiac function during early mouse embryogenesis coincides with entry of primitive erythroblasts into the embryo proper. Circ. Res. 2003;92:133–135. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000056532.18710.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phoon CK, Aristizabal O, Turnbull DH. Spatial velocity profile in mouse embryonic aorta and Doppler-derived volumetric flow: a preliminary model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2002;283:H908–H916. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00869.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones EA, Baron MH, Fraser SE, Dickinson ME. Measuring hemodynamic changes during mammalian development. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H1561–H1569. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00081.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nosek TM. Essentials of Human physiology — Cardiac and Circulatory Physiology. Gold Standard Multimedia; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackman BR, Garcia-Cardena G, Gimbrone MA., Jr A new in vitro model to evaluate differential responses of endothelial cells to simulated arterial shear stress waveforms. J. Biomech. Eng. 2002;124:397–407. doi: 10.1115/1.1486468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Y, Yates F, Naveiras O, Ernst P, Daley GQ. Embryonic stemcell-derived hematopoietic stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:19081–19086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506127102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tiboni GM, Marotta F, Barbacane L. Production of axial skeletalmalformations with the nitric oxide synthesis inhibitorNG-nitro-l-argininemethyl ester (L-NAME) in the mouse. Birth Defects Res. B Dev. Reprod. Toxicol. 2007;80:28–33. doi: 10.1002/bdrb.20100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.