Summary

Villin is an F-actin nucleating, crosslinking, severing, and capping protein within the gelsolin superfamily. We have used electron tomography of 2D arrays of villin-crosslinked F-actin to generate the first 3D images revealing villin’s crosslinking structure. In these polar arrays, neighboring filaments are spaced 125.9 ± 7.1 Å apart, offset axially by 17 Å, with one villin crosslink per actin crossover. More than 6,500 sub-volumes containing a single villin crosslink and the neighboring actin filaments were aligned and classified to produce 3D sub-volume averages. Placement of a complete villin homology model into the average density reveals that full-length villin binds to different sites on F-actin than those used by other actin-binding proteins and villin’s close homolog gelsolin.

Introduction

Villin, a ~95 kD actin crosslinking protein, is a member of the gelsolin superfamily (Bretscher and Weber, 1980). Gelsolin family proteins regulate F-actin length by severing filaments and/or capping the barbed ends. Each member has three or six homologous copies of a 120 amino acid (~14 kD) domain, the gelsolin-like domain. Gelsolin and villin each have six such domains, denoted here as G1–G6 and V1–V6 respectively. Villin has 45% amino acid sequence identity with gelsolin over the six domains (Finidori et al., 1992) suggesting that their tertiary structures are very similar. Gelsolin cannot crosslink F-actin while villin can, a property attributed to the presence of a small, 76 amino acid “head piece” domain at villin’s C-terminus (Glenney et al., 1981).

Villin can nucleate actin polymerization, crosslink filaments, sever F-actin at high [Ca2+] or following tyrosine phosphorylation, and cap the barbed ends of filaments. Much of what is inferred about villin function and structure comes from a comparison with gelsolin, its closest homolog. Gelsolin’s function is regulated by calcium binding at up to eight different sites. At submicromolar [Ca2+], gelsolin folds into a compact autoinhibited state which places the tail-helix of the C-terminal G6 domain close to G2 creating a steric block to G2 binding of F-actin (Burtnick et al., 1997). Calcium binding to the Type 2 (intradomain) site within G6 releases this inhibition (Choe et al., 2002). Further calcium effects involve domain rearrangements that release “latch” mechanisms between G1 and G3 to activate the G1 actin-binding site, and between G4 and G6 to allow G4 to participate in actin capping (Choe et al., 2002). Further interaction of G1 and G4 with the filament via Type 1 (interdomain) Ca2+ ion coordination between actin and gelsolin, leads to severing and capping. The severing mechanism requires micromolar [Ca2+] (Yin and Stossel, 1979).

Villin, in contrast, has only three established calcium-binding sites (Hesterberg and Weber, 1983a) and requires [Ca2+] as high as 200 μM to activate severing. Such concentrations are not usually found in live cells, but might occur in apoptotic cells. Tyrosine phosphorylation of villin can reduce or even eliminate the calcium binding requirement for severing, suggesting that phosphorylation may be the primary regulator of villin conformation (Kumar and Khurana, 2004).

The crystal structure of gelsolin’s domain G1 in complex with G-actin (McLaughlin et al., 1993) revealed G1 bound in the hydrophobic pocket between actin subdomains 1 and 3 where it caps the F-actin barbed end. The crystal structure of G1–G3 in combination with calcium and G-actin identified the unique G2–G3 actin side-binding position (Burtnick et al., 2004) that competes with α-actinin for F-actin binding (Way et al., 1992). EM difference mapping of G2–G6 decorated F-actin in the presence of calcium localized the G2 binding site on the side of F-actin, but the rest of the molecule was disordered (McGough et al., 1998). The C-terminal half, G4–G6, has similarly been crystallized with calcium and G-actin and shows that G4 binds to G-actin in a similar fashion as G1 (Choe et al., 2002). The crystal structure of full length gelsolin in the inactive, calcium-free state revealed a compact, autoinhibited form in which G6 and G2 interact to form the above-mentioned “tail-helix latch” that prevents the actin-binding regions from contacting actin (Burtnick et al., 1997). Small angle X-ray scattering of gelsolin revealed global conformational changes with increasing calcium and highly flexible interdomain linkers (Ashish et al., 2007).

Structural data for villin are limited. Hydrodynamic and spectroscopic studies have shown that villin in solution undergoes a large calcium induced conformational shift to become more asymmetric with an overall length increase from 84 to 123 Å (Hesterberg and Weber, 1983b). These data led Hesterberg and Weber to suggest a “hinge-mechanism” where calcium binding creates a localized tightening of the villin structure coupled to an outward shift of another domain (presumably the head piece) into solution. Recently two potential “latch” residues have been identified based on sequence homology to gelsolin, Asp467 and Asp715, that potentially form salt-bridges with a cluster of basic residues in villin domain V2 (Kumar and Khurana, 2004). However, no clear demonstration of villin in a folded, autoinhibited state exists.

The solution NMR structure of V1, a.k.a. villin 14T, revealed an overall fold that is very similar to that of gelsolin G1 as predicted by the high sequence identity (Markus et al., 1997; Markus et al., 1994). Several structures exist for the villin head piece domain (Frank et al., 2004; McKnight et al., 1997; Meng et al., 2005; Vardar et al., 1999; Vermeulen et al., 2004). Cysteine scanning mutagenesis of this domain has provided comprehensive data for the surface distribution of basic residues and their presentation to actin (Doering and Matsudaira, 1996). A recent NMR structure of a V6–headpiece construct demonstrated that the 40 amino acid connecting linker is unfolded and disordered (Smirnov et al., 2007).

Villin and fimbrin, another actin crosslinking protein, are found together in the actin core of finger-like projections known as microvilli in intestinal epithelium and kidney proximal tubules. Each microvillus contains 20+ polar actin filaments (Tilney and Mooseker, 1971). In the normal microvillus, actin filaments are separated laterally by ~125 Å (DeRosier et al., 1977). Microvilli form in villin-deficient mice but they lack the typical discrete F-actin bundles within the core (Ferrary et al., 1999; Pinson et al., 1998), suggesting that while the loss of villin can be partially compensated by fimbrin, the finer structure of the microvillus may be specific to villin’s functions. Moreover, villin’s ability to induce microvillus formation is a function of its crosslinking ability, not its nucleating ability (Friederich et al., 1999). It is not known how both fimbrin and villin cooperate in the microvillus core or in vitro to bundle F-actin. Each crosslinking protein by itself may produce its own preferred F-actin bundle geometry, while in combination, a single compromise bundle geometry may occur.

Two types of 2D arrays are formed when fimbrin crosslinks F-actin on a lipid monolayer which suggests polymorphism among fimbrin crosslinks (Volkmann et al., 2001). In one type, adjacent filaments are in axial register, while in the second, adjacent filaments are displaced axially by 55 Å. This raises the question of whether the addition of villin crosslinks would favor one form of fimbrin crosslink over the other.

Here we employ electron tomography of F-actin:villin 2D arrays to learn in 3D how villin interacts with and crosslinks F-actin in low [Ca2+]. The 2D arrays provide a format to study the actin bound structure of proteins that interact weakly with actin and have a tendency to form bundles either in vitro or in vivo and helps define specific protein-actin interactions as well as any polymorphisms in the crosslinked filaments. Using multivariate data analysis (MDA) of sub-volumes extracted from the tomograms, we show that the villin-actin contacts are homogeneous and different from contacts for other actin-binding proteins. Without calcium to activate it, villin can crosslink F-actin without disrupting the filaments. We find that the filament arrangement in F-actin:villin 2D arrays differs from F-actin:fimbrin 2D arrays suggesting that 3D actin bundles in microvilli involve arriving at a compromise structure or bonding rule. We also explore the novelty of these villin-actin contacts in the context of villin’s homology with gelsolin.

Results

Image Alignment and Volume Classification

In the presence of EGTA, villin forms regularly spaced crosslinks along F-actin in 2D paracrystalline arrays ≥1 μm wide formed on lipid monolayers. We collected six different single-axis tilt series and computed six tomograms. Sub-volumes were combined after initial alignment on the actin filaments. Resolution was truncated to 38 Å consistent with the position of the first node of the CTF. The villin crosslinks, which occur once per actin crossover, appear as long, extended “squiggles” in the raw tomogram (Figure 1A, Supplemental Figure S1A), measuring between 126 and 140 Å in length. The measured volume of 130.2 × 103 Å3 for the villin crosslink indicates that 95 kD villin binds as a monomer. Actin filaments are predominantly separated by 126 Å (Table 1), a separation that is close to the value of ~120 Å found for arrays of actin and fimbrin (Volkmann et al., 2001) and nearly identical to values obtained for microvilli (DeRosier et al., 1977; Matsudaira et al., 1983).

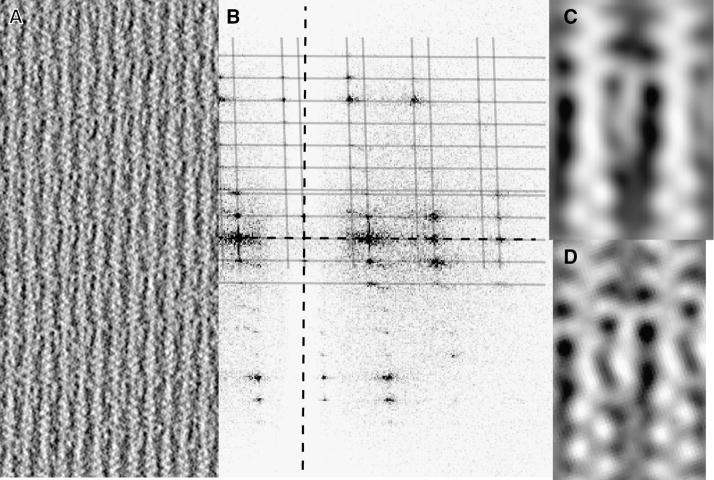

Figure 1.

Electron micrographs of F-actin:villin crosslinks. (A) Electron micrograph of a well ordered segment from Tomogram 1 (Table 1). Protein is white. (B) Fourier transform of the raft shown in (A). The meridional and equatorial axes are shown in black dashed lines, layer lines and row lines are in gray. (C) Projection image of the 3D global average of ~6,500 aligned villin crosslink repeats. (D) Averaged 2D projection image of ice embedded specimens, for comparison.

Table I.

F-actin-villin Raft Parameters

| Tomogram | Actin Symmetry | Interfilament Spacing (Å) | Filament Shift (Å) | σtrans | Filament Rotation | σrot | Ideal Rotation | Filaments/repeat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80/37 | 125.3 | 16.3a | 2.2 | 5.7°c | 1.1 | 5.4° | 5 |

| 2 | 186/86 | 129.5 | 16.9a | 2.4 | 10.0°c | 2.0 | 9.0° | 3 |

| 3 | 80/37 | 125.3 | 16.9a | 1.2 | 5.5°c | 1.2 | 5.4° | 5 |

| 4 | 13/6 | 133.4 | 17.5b | - | 0.0° | - | 0.0° | 1 |

| 5 | 186/86 | 112.5 | 27.0b | - | 0.0° | - | 0.0° | 1 |

| 6 | 54/25 | 129.7 | 17.1b | - | 0.0° | - | 0.0° | 1 |

| Average | 125.9 | 18.6 | ||||||

| σ | 7.1 | 4.1 |

Calculated from Equation (13) of Sukow & DeRosier (1998) using the idealized filament rotation in column 8

Calculated from the reciprocal lattice vectors.

Calculated from Equation (13) of Sukow & DeRosier (1998) using an average filament translation of 17.3 Å (average from tomograms 4 and 6)

Actin filaments in the arrays varied in their helical symmetries and their rotational orientations. Computed Fourier transforms of well ordered regions within each of the six tomograms (e.g. Figure 1B, Supplemental Figure 1B) were analyzed according to Sukow and DeRosier (1998). Predominately, each neighboring filament is axially shifted 16.9 ± 0.4 Å up, from left to right (Table 1). The shift was confirmed from measurements made on two global averages, one in negative stain (Fig. 1C) and one in ice (Fig. 1D). Of the well-ordered arrays analyzed, three showed no rotation between adjacent actin filaments, two showed a rotation of 5.4° and one showed a rotation of 10°. Actin filament symmetries varied from 13/6 (166.15° rotation between actin subunits) to 54/25 (166.67°). One array in Table 1 (#5) showed a 17Å smaller interfilament spacing and a 27Å axial offset, values more than 3σ different from the averages of the other five.

The axial rotational differences between adjacent filaments were also determined by rotational cross correlation in 1° steps. Although less accurate than the raft analysis described above because the missing wedge may affect the alignment, it measures the entire set of crosslinks. Histograms of the rotation angles show predominately three groups centered on 0°, 5° and 10° (Figure S2), consistent with the raft analysis. The most favored rotation by far is 0°, while there is little difference in the frequency of occurrence for 5°–6° and 9°–11°. The average axial shift obtained from this analysis was 13.5 ± 3.7Å, in agreement with that determined from the array analysis. Thus, while the axial shift seemed fixed at 17Å, variations of up to 10° in filament rotation appeared to be tolerated.

The global average of the aligned sub-volumes shows clearly the shape of the villin and its location relative to the actin subunits (Figure 1C). The 17Å axial filament shift brings the right side actin subunit closer to the left side subunit. Thus, the actin subunits that interact with villin are offset axially only 27–17=10Å. Three contacts are seen between villin and actin, two across the top and one on the left side at the bottom. These contacts are also seen in the projection of frozen-hydrated arrays (Figure 1D). The two projections are virtually identical showing that the structures of negatively stained arrays are the same as those in frozen-hydrated arrays.

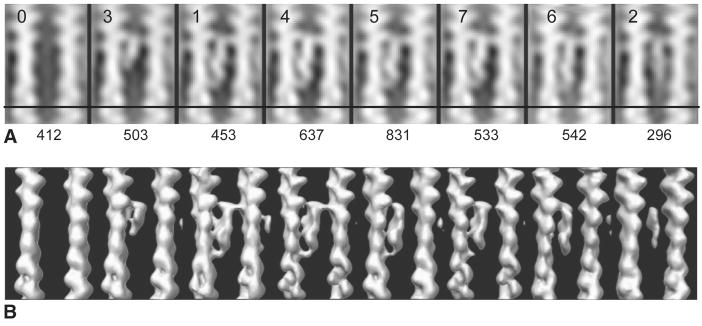

Using MDA (Winkler and Taylor, 1999) we separately characterized the heterogeneity in the actin filaments and the villin crosslinks during our initial rounds of alignment. Once the sub-volumes were sufficiently aligned to the global average, further classification of the villin crosslink was done based on the variance calculated in the region of the villin density. The resulting class averages (Figure 2) show that, in some cases, potential villin crosslinking sites were unoccupied, some sites show partial villin density, while other variations can be explained by villin flexibility. The partial villin density could be attributed either to negative staining effects, or proteolysis since villin, like gelsolin, is susceptible to cleavage of its long inter-domain linkers (Bazari et al., 1988).

Figure 2.

Class averages based on the variance within the villin crosslink. Labels across the top are in order of relatedness from the classification. Numbers at the bottom are the number of class members. (A) Projection images. Class average 1 shows incomplete “half-villin” density. Average 0 has no villin crosslink. Class average 2 illustrates a fraction of crosslinks that are highly variable at one end. (B) Same averages as above, but shown as volumes. All averages in (B) are contoured to the same threshold.

An F-Actin-Villin Crosslink Model

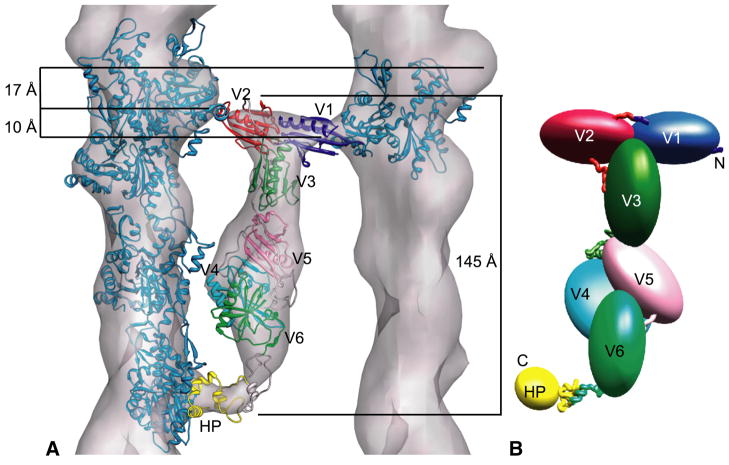

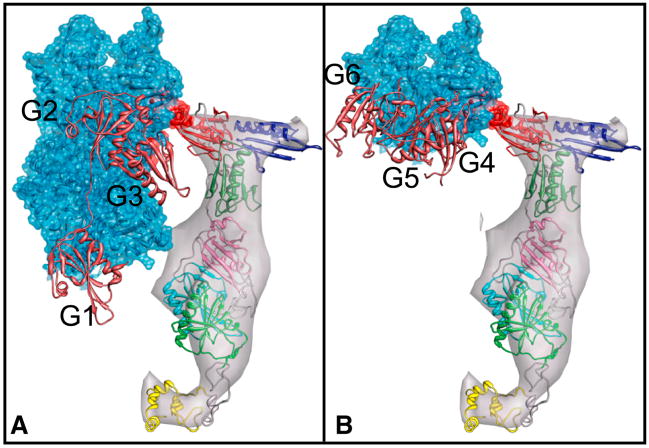

By rigid body fitting, we docked the atomic model for a 13/6 actin filament into our F-actin volume in the tomogram. A quasiatomic model for chicken villin was created (see Experimental Procedures) based on the known structures of villin domains V1 and head piece and homology models from gelsolin for domains V2–V6. We then placed V1, V2, V3, and the headpiece as individual domains into the villin volume, and placed V4–V6 as a group (Figure 3). In the class averages there appear to be at least three contacts of villin with the actin filament, with a fourth possible. The two contacts at the top of the density are far enough apart to accommodate two gelsolin domains (Figures 3A, 4A). These are tentatively labeled V1 and V2, since at this resolution it is impossible to distinguish them. Because of the connecting linker, it is also not possible to determine with certainty the orientation of V1 and V2. The small tail region fits the villin head piece structure, but is too small for a gelsolin-like domain (Figure 4D). Likewise, the head piece is too small for the V1–V2 density (Figure 4C). The head piece crown of positive charge, located on the C-terminal helix, was placed facing the actin filament (Figures 3, 4B) according to the fitting of the dematin headpiece on F-actin (Chen et al., 2003). The 40 amino acid unfolded linker between V6 and the headpiece may explain the thin and variable crook of density we see leading from the villin core to the F-actin interacting site (Smirnov et al., 2007). This same weak density corresponding to the N-terminus of the headpiece was observed by Chen et al. in an EM map of the dematin head piece-decorated F-actin (Chen et al., 2003). The dematin headpiece has ~47% sequence identity with villin headpiece (Rana et al., 1993).

Figure 3.

Model of villin crosslinking F-actin. (A) Placement of the villin homology model atomic coordinates within the averaged villin density. (B) Schematic of villin domain topology with the approximate location of linkers shown

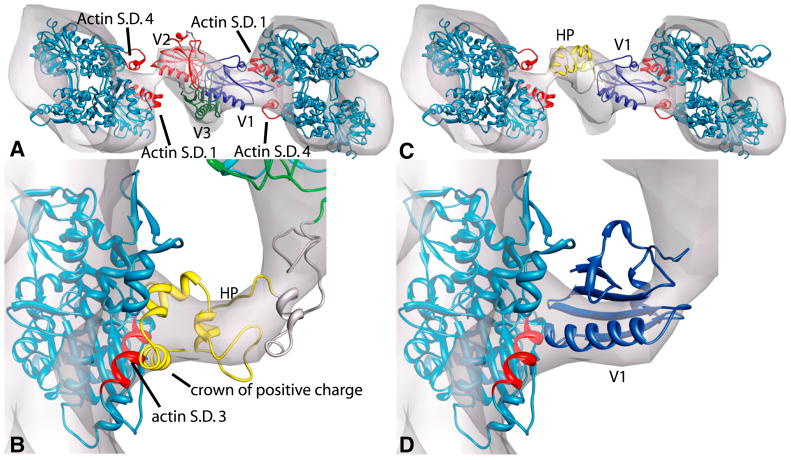

Figure 4.

Close-up of villin-actin interactions. (A) A top-down view of the model in Figure 3. The N-terminus of the long V2 helix, residues 151-158, points between two actin subunits. On the left hand filament, which is interacting with villin domain V2 (red), the actin subdomain 1 (S.D. 1) helices, residues 112-126 and 358-365 of one subunit and on the next subunit up, actin subdomain 4 (S.D. 4) helix residues 222-236, all of which are involved in villin interaction, are shown in red. Likewise, V1 (blue) is positioned between the same regions of actin on the right hand filament. (B) Position of the villin head piece. The head piece helix residues 62-76, which include the “crown of positive charge”, are positioned towards actin and in the vicinity of helix residues 308-320 on actin subdomain 3 (S.D. 3). The disordered linker can be readily accommodated within the linker density. (C) Replacement of V2 by the head piece. The head piece is too small for the V2 density. (D) Replacement of head piece by V1. The gelsolin-like domain is too large for this density. Thus, the head piece placement determines the overall orientation of the villin cross-link model.

Perhaps the most curious aspect of the villin contacts with F-actin is that the location on actin is different from that of other actin-binding proteins. The arrangement of V1 and V2 within the density indicates an interaction with actin subdomains 1 and/or 4 unlike those typical for gelsolin-like domains (Burtnick et al., 2004; Choe et al., 2002). G1 binds in a hydrophobic pocket between actin subdomains 1 and 3 (Figures 4,S3). However, binding of G1 is characteristic of end-capping proteins. The ABD (actin-binding domain) of α-actinin binds to two adjacent actin protomers by contacting subdomain 1 and 2 on one actin protomer and subdomain 1 of the next protomer up the filament. This corresponds to actin residues 86–117 of the lower protomer and residues 350–375 of the upper protomer (Fabbrizio et al., 1993; Lebart et al., 1990; Lebart et al., 1993; McGough et al., 1994; Mimura and Asano, 1987). The gelsolin G2 domain has a similar actin interaction (McGough et al., 1998). Although the loops on the ends of the actin-binding helices in V1 and V2 are in close proximity to actin residues 358–365 (Figure 5), the rest of the protein density is oriented back and away from the α-actinin/G2 binding region.

Figure 5.

Villin and gelsolin binding sites do not overlap. Villin density map and atomic model are shown next to gelsolin crystal structures (colored copper) bound to actin. (A) N-terminus of gelsolin bound to actin as in the crystal structure. G2 binds via its long α-helix, the “actin binding helix”, between actin subdomains 1 and 3; G3 does not make contact with actin. G1 bound in this manner effectively caps the barbed end of the filament (PDB 1RGI). (B) C-terminus of gelsolin bound to actin. G4 makes contact with actin subdomain 3. G5 and G6 are not bound to actin; however, the long α-helix of G6 is in close proximity to helices of actin subdomains 3 and 4 (PDB 1H1V).

Although the exact binding site of villin’s headpiece on F-actin is unknown, competition-binding assays have indicated that the villin head piece can displace the binding of actin depolymerizing factor, which suggests that it binds to actin in the same hydrophobic binding pocket as G1 and other capping proteins (Pope et al., 1994). However, the position of the villin head piece density in our reconstruction is not in this hydrophobic pocket. Instead, it is positioned near two α-helices, one from actin subdomain 3 (residues 308–320) and one from subdomain 4 (residues 222–236). The headpiece localization is invariant among the class averages.

Compatibility with the F-Actin:Fimbrin Crosslink Model

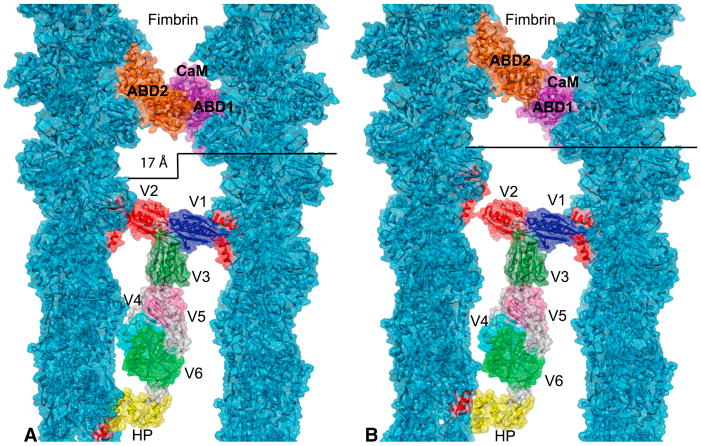

The F-actin:fimbrin 2D arrays and the F-actin:villin 2D arrays have different geometries, the former has either 0 or 55 Å offsets, and the latter have a 17 Å offset, which raises the question of what types of changes would be required to place the villin model into the F-actin:fimbrin crosslink model. We explored this in two ways (Figure 6). For both models, we built a modified F-actin:fimbrin crosslink by combining the coordinates of the F-actin:fimbrin crosslink from Volkmann et al. (2001) with recent data for the interaction of fimbrin’s ABD2 with F-actin from Galkin et al. (2008). The first model (Figure 6A) was built using the 17 Å filament offset with a modified fimbrin crosslink. Despite the offset, the two fimbrin coordinate sets could be placed on actin as determined separately without steric clash. Recent results on the structure of F-actin decorated with fimbrin ABDs indicate that the actin-bound ABD1 is poorly ordered suggesting flexibility or polymorphism in one of its CH domains’ interaction with actin (Galkin et al., 2008).

Figure 6.

Fimbrin and the F-actin:villin crosslink model. To demonstrate compatibility between these two co-crosslinkers we placed the atomic coordinates of fimbrin ABD2 (orange) on the left-hand actin filament and ABD1 and calmodulin-like domain (violet) on the closest right-hand actin monomer. It is not known exactly how these domains interact with one another in a crosslink but all are accommodated within the context of our model without a steric clash. (A) Model built with the two actin filaments offset by 17Å. (B) Model built with the two actin filaments in axial register. In this model, the interaction between V2 and actin must be broken and the head piece linker rebuilt.

For the second model (Figure 6B), we remodeled fimbrin as described above as well as villin and kept the filaments in axial register with no offset. A villin crosslinker must bind both actin filaments and this could be accomplished using no axial offset by eliminating the V2-actin interaction. V2 still remains close to actin, but any residual interaction must involve different surfaces of both V2 and actin. The head piece linkage to V6 also required remodeling but it is known to be flexible.

Discussion

Villin is a compact 84 Å molecule in solution but extends to about 123 Å on the binding of calcium (Hesterberg and Weber, 1983b). Our map is well fit by an extended villin molecule and bears a striking similarity to a recent structure obtained by small angle X-ray scattering of Ca2+-activated gelsolin (Ashish et al., 2007). However, our specimens are formed in low [Ca2+] and with actin. Although we do not know if the villin conformation in the crosslink is the same as that in an actin-free calcium medium, the two forms of these highly similar molecules, one compact, the other extended, reinforce the hypothesis that villin contains a number of flexible hinges.

Villin Forms a Unique F-actin Crosslink

The class averages of F-actin-villin were surprisingly similar (Fig. 4) consistent with constancy of villin-actin contacts. Polymorphism in the arrays is largely due to differences in rotations of adjacent actin filaments around the filament axis. The glancing contacts of villin at the outermost edge of the actin protomers (Figures 3, 4A, 5) suggests that each bond contributes only weakly to the total binding. Multiplicity of weak interaction sites, in fact at least three such sites, cooperatively stabilizes the crosslinking in the presence of the high F-actin concentration in the microvillus. It would also give villin a dynamic interaction with the actin bundle, allowing it to rapidly convert between different bound configurations.

Unlike gelsolin, villin possesses an F-actin crosslinking activity, which was largely thought to reside in its unique headpiece. However, headpiece by itself cannot crosslink filaments, unless villin crosslinks as a dimer, which our data shows is not the case. We suspect that headpiece is essential for holding villin on F-actin and that crosslinking occurs via V1–V2. In the quasiatomic model, end-loops on V1 and V2, both of which contain arginine and lysine residues, are placed on an acidic α-helix of actin subdomains 1 and 4 forming a predominately electrostatic association. The buried surface is small suggesting a weak and dynamic interaction. It is not known whether a V1–V3 villin fragment could crosslink actin filaments on its own, as suggested by one of our class averages, but optimal placement of the actin filaments produced by full length villin crosslinks may be an important factor in the present case.

Comparison with F-actin:Fimbrin Arrays

The organization of filaments in F-actin:fimbrin arrays differs from that found in F-actin:villin arrays. Filament separation in F-actin:fimbrin arrays is ~120Å whereas it is 126Å in F-actin:villin arrays, identical to that found in microvilli. Fimbrin also formed two types of arrays, one with 0Å and the other with 55Å axial offset between neighboring filaments. Both fimbrin arrays, on average, have no relative rotation between actin filaments. F-actin:villin arrays have a consistent 17Å axial shift between neighboring actin filaments but a variable 0° to 10° filament rotation. Our results show that the fimbrin and villin binding sites in the bundles do not overlap so that coexistence in the same bundle is possible. In other respects, some accommodation is necessary for an integrated bundle geometry.

It would appear that for villin and fimbrin to coexist in the same microvillar bundle requires either villin, fimbrin, or both to alter their mode of interaction with actin to accommodate the difference in preferred actin filament offsets with perhaps the linkers between domains performing a key role. It is somewhat surprising that fimbrin, with shorter linkers between its ABDs, demonstrates two different crosslink geometries while villin, possessing long linkers between domains, demonstrates a single geometry.

The model shown in Figure 6A suggests that the 17Å offset seems to be compatible for forming a fimbrin crosslink. At minimum two contacts by villin are required for crosslinking. Our modeling (Figure 6B) suggests that a minimal villin crosslink could adapt to the axially aligned filament geometry dictated by fimbrin by eliminating the V2-actin bond and remodeling the link between the villin head piece and V6 to accommodate the 17Å shift. While plausible, the crosslink would probably be less energetically favorable compared to the 3-bond crosslink seen in the F-actin:villin rafts. Another possibility is that once localized in the densely-packed microvillus, villin could play a passive role in bundle geometry by simply binding to the side of a single actin filament using the V2 and headpiece binding sites. However, side binding would be less effective for targeting to the microvillus than crosslinking which is a function of bundle geometry. Either way, the ability of villin to determine/dictate the physical geometry of the bundle is reduced because one interaction is lost.

Both villin and fimbrin crosslinks produce exceptionally high local actin concentrations negating the need for strong actin affinity for bundling. Cooperativity among multiple binding sites would stabilize the bundle. With weak interactions, the off rates for any one of the villin-actin bonds would be high, promoting the ability to change conformation quickly if conditions change. The high local actin concentration would produce high on rates that keep villin concentrated within the bundle. If fimbrin is the dominant influence on the bundle structure, possibly villin would have only two binding sites making it highly dynamic in vivo. Multiple weak interactions could serve as a positioning/locating mechanism for villin on the filaments, facilitating concentration of villin into the bundle, even if the rate might be slow. In high [Ca2+], both fimbrin and villin would loose their crosslinking capability, so that the bundle would collapse rapidly with no active crosslinkers and an active severing protein embedded within it. We envision a scenario of quick conversion from bundling to severing without large scale diffusion of villin, confining actin filament cleavage to a localized area.

Implications for In Vivo Actin Bundles

Theoretically, one way to form a hexagonal bundle of actin filaments using a single crosslinker is for the actin filaments to all be arranged in axial register (DeRosier and Tilney, 1982). This allows a single quasi-equivalent bonding rule to define all the crosslinks, even for actin filaments with different helical pitch. However, there are published examples of images and diffraction patterns of actin bundles possessing well oriented actin filaments with crossovers having regular offsets (DeRosier et al., 1977; DeRosier and Tilney, 1982; Tilney et al., 1980). Indeed, one report (DeRosier and Tilney, 1982) observed an axial offset of 18Å in the actin bundles in stereocilia, in which fimbrin is the dominant crosslinker. However, these offsets are generally attributed to bending of the actin bundle (Tilney et al., 1983) rather than to a general feature of the bundle organization.

The formation of hexagonal bundles of actin filaments with a regular twist requires that the crosslinkers tolerate 4–5° of azimuthal variation in the orientation of their actin binding sites (DeRosier and Tilney, 1982). Local variations in the F-actin helical twist (Egelman et al., 1982) or even actin protomer flexibility may reduce this amount. Assuming the helix is regular, our results show that villin crosslinks form with azimuthal variations between actin filaments of up to 10°. On this criterion, villin appears to be well suited for a crosslinking role in a hexagonal bundle. In other ways, villin appears to be poorly suited to hexagonal bundle formation.

At a minimum, two actin contacts are required for villin to crosslink F-actin, one on V1 and the other on the headpiece. However, our reconstructions show three: an additional contact is formed by V2. We think that the rigid selection of a 17Å offset is determined by the V1–V2 arrangement because the density connecting the head piece with V6 is very thin, suggesting flexibility in this location, consistent with the disorder observed in solution (Smirnov et al., 2007). Flexibility between the headpiece and V6 would make the headpiece an effective crosslinker under a variety of conditions, but poor with respect to enforcing a particular geometry. In addition, one class average having the same 17Å offset as the others appeared to contain a villin molecule truncated after V3 and therefore had no villin head piece (#3 in Figure 2) but still retained the V1–V2 arrangement. We suspect that a flexible headpiece would allow villin to accommodate a filament arrangement, specifically a filament alignment between crosslinked actins dictated by the fimbrin crosslinks. Unlike the other gelsolin-like domains, V1 and V2 appear to be relatively inflexibly joined; otherwise, there should be more variation in the actin filament offsets. In the class average used for quasiatomic model building, the density connecting headpiece and V6 is narrow but would accommodate the linker in a folded conformation (although our structure here is entirely hypothetical), suggesting that crosslinking may induce a folded state of this otherwise mobile segment. However, other classes show even less linker density, consistent with high flexibility.

The apparent incompatibility between F-actin:villin bundles and F-actin:fimbrin bundles may be explicable in two ways. Villin is not necessary for formation of microvilli, but its absence leads to poorly ordered bundles (Pinson et al., 1998). Villin appears early in microvilli formation and is followed by fimbrin (Ezzell et al., 1989). If villin appears early, it might favor formation of crosslinks with 17Å offsets. An offset of 17Å is closer to the aligned crosslink produced by fimbrin, rather than the alternative 55Å offset that fimbrin can form. Our modeling suggests that with a 17Å offset, fimbrin can form a crosslink, which we speculate would anneal/adjust to one with no offset as long as the villin bonds are forming and dissociating rapidly, which our structure suggests is indeed the case. Villin would then be the agent favoring an aligned bundle. Its absence would force a disordered bundle as fimbrin by itself would form crosslinks with different offsets. Villin, having multiple weak and variable interactions with actin, would be retained in the aligned bundle where it performs an important role for remodeling and disassembly of the microvilli (Glenney et al., 1980).

Villin’s multiple weak interactions with actin would also be important for the mechanical characteristics of the bundle. Villin and fimbrin occur in approximately equal quantities in the microvillus (Matsudaira and Burgess, 1979) and our results show that their interaction sites do not compete with each other. If villin crosslinked actin as strongly as fimbrin, it would have important consequences for the mechanical characteristics of the bundle. Fimbrin by itself has crosslinking characteristics that are ideal to accommodate bending in the bundle (Claessens et al., 2006). Villin, as a weak actin binder would have dynamic bonds with rapid on and off rates that may have little affect on the mechanical properties of the bundle while permitting villin to occupy the bundle in high concentration.

Modes of F-actin Binding Among Homologous Domains

It is commonly assumed that homologous actin binding proteins interact similarly with actin although this is not always the case as shown for the widely studied ABDs composed of calponin homology domains which include those of fimbrin, α-actinin, utrophin, dystrophin and calponin itself (Galkin et al., 2008; Galkin et al., 2006). Our research identifies a novel interaction between actin and villin that is not predicted by actin-bound structures of villin’s closest homolog gelsolin and bears on the question of similarity of actin interactions by homologous proteins.

Despite the high sequence identity between villin and gelsolin in the six main domains, the F-actin:villin interactions observed here are uncharacteristic when compared to the known interactions of gelsolin with F-actin or G-actin. However, our work pertains to a capability of villin for interacting with actin in low [Ca2+] that gelsolin completely lacks. Villin’s actin crosslinking activity is present in low [Ca2+], under which conditions, its severing and capping activity are minimal. Essentially, villin crosslinks F-actin while in its enzymatically “inactive” state. Gelsolin is also enzymatically inactive in low [Ca2+] and forms a folded conformation that blocks its surfaces that participate in actin binding, severing and capping. Our reconstructions show that the villin “inactive” state bears no resemblance to the gelsolin inactive state. In low [Ca2+], the homologous actin interaction sites of gelsolin are not placed appropriately for F-actin crosslinking as they are in villin. It is therefore not surprising that the F-actin-villin crosslinks in low [Ca2+] cannot be predicted by gelsolin-actin interactions in high [Ca2+]. Interactions with F-actin in high [Ca2+], under which conditions both villin and gelsolin cap and sever F-actin, could be closely parallel, but that remains to be shown. It also remains to be determined whether villin forms a gelsolin-like inactive conformation in the absence of F-actin which would imply that actin induces a conformational change that results in crosslinking. That the more than 6,500 villin crosslinks were so homogeneous in their structure suggests that what we have observed is not an exceptional case for actin interaction in this protein, but rather a legitimate mode of interaction for gelsolin-like domains. This is a further illustration that inferring protein:protein interactions based on homology alone may be misleading unless the functional roles are also homologous.

In summary, we have used electron tomography of 2D F-actin:villin arrays and sub-volume classification to obtain the first 3D image of villin in a crosslinking role. The structure of the villin crosslinks and the interactions of the individual villin domains with actin could not have been predicted from the known gelsolin-actin structures. The specific geometry of the 2D arrays determined by the villin crosslink is different from that found in F-actin:fimbrin arrays. However, villin possesses some rather long inter-domain linkers, which may facilitate accommodation of villin into actin bundles whose structure is determined by fimbrin crosslinks. Our modeling suggests that villin has sufficient flexibility to bind or crosslink F-actin in cooperation with fimbrin in the microvillus thereby stabilizing the structure and at the same time, embedding within it the apparatus for rapid disassembly.

Experimental Procedures

Protein Purification and Array Formation

Villin was purified from chicken intestines (Burgess et al., 1987). Actin was prepared from rabbit muscle acetone powder (Pardee and Spudich, 1982), followed by a Superose-12 column. Fresh G-actin was prepared by dialysis overnight ahgainst Buffer A:2 mM Tris-Cl, 0.2 mM Na2ATP, 0.02% β-mercaptoethanol, 0.2 mM CaCl2, 0.01% NaN3, pH 8.0. The protein was clarified by high-speed centrifugation prior to sample set-up. Arrays were grown on positively charged lipid monolayers (Taylor and Taylor, 1994). A 3:7 volume ratio of DLPC:DDMA lipids (Avanti Polar Lipids) at 1 mg/mL in chloroform was layered over a solution containing 0.35 μM α-actin and 0.14 – 0.17 μM villin in phosphate-buffered polymerizing buffer without CaCl2 and with 1 mM EGTA, pH 6.5. The actin was polymerized in the presence of villin at 4°C.

EM data collection

The 2D arrays were recovered using 200–300 mesh copper grids with a reticulated carbon support film (Kubalek et al., 1991). Samples were stained with 2% uranyl acetate, dried, and stabilized by a thin layer of evaporated carbon. Data were collected on a Philips CM300-FEG. Six tomograms were recorded at 24k magnification with 1.8x post magnification at the CCD camera. The sample was tilted using a 2° Saxton scheme (Saxton and Baumeister, 1982) and recorded on a 2k × 2k CCD camera (TVIPS, GMBH, Gauting, Germany).

Image Processing

Tilt series were aligned using marker-free alignment (Winkler and Taylor, 2006). Repeat coordinates centered on each actin crossover from each tomogram were manually picked using the EMAN Boxer utility (Ludtke et al., 1999). 6,566 raw repeats were extracted as 64 × 144 × 40 voxel boxes. Images were then normalized by subtracting the mean and scaling the standard deviation to 1. Repeats from each tomogram were aligned in 3D to the two crosslinked actin filaments using in-house software. After the best alignments were attained, as judged by classification of the actin filaments, the repeats from each tomogram were compiled into a single data set and aligned once more to the global average.

Classification

Aligned subvolumes were classified using MDA with a 3-D mask derived from the variance map of the global average. Classifications were done using between 8–32 factors, but ones made with the top 16 gave the best results. The number of factors (Eigenimages) used in the classification was determined by inspecting each factor and from a plot of the variance (Eigenvalues) as a function of factor number.

Analysis of 2D Array Structure

Regions of homogeneous crosslinks were boxed from each tomogram, projected and their Fourier transforms calculated after padding into a square array. The layer line and row line spacing was determined from the transforms and the reciprocal lattice drawn. Vertical row lines were placed over the three inner layer lines, 0, 1 and 2 and over the outer layer lines, 5, 6 and 7. When the two sets of row lines intersect, there is no rotation between neighboring filaments and when they do not, there is a rotation about the filament axis, the amount of which can be determined, provided that the axial translation is known. This analysis also determined the helical symmetry.

Modeling

The PDB coordinates of an actin monomer were used to generate an atomic model of F-actin with 13/6 helical symmetry (PDB 1ATN). Homology models for chicken villin (accession P02640) were created using SWISS-MODEL (Schwede et al., 2003) based on the structures for villin 14T (PDB 2VIK), gelsolin domains G2–G3 in an open conformation (PDB 1RGI), the gelsolin G3–G4 linker through G6 in the closed conformation (PDB 1D06), and the villin headpiece (PDB 1YU5). The disordered sequence linking V6 to the headpiece was modeled based on other flexible linkers from the above structures. Manipulation of the pdb files and energy minimization was performed using the MMTSB toolset (Feig et al., 2004). Coordinates were checked with PROCHECK (Laskowski et al., 1993). Models of villin crosslinks were created in Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Hanspeter Winkler for his guidance, Drs. Niels Volkmann and Dorit Hanein for providing their actin:fimbrin crosslink coordinates, Dr. Edward Egelman for the fimbrin ABD2 coordinates, Ms. Greta Ouyang for the preparation of villin protein and the 2D F-actin:villin class average in ice and David Burgess for teaching us how to make villin. This research supported by NIH Grant U54 GM64346 to the Cell Migration Consortium. The tomograms, their metadata, aligned sub-volumes and quasiatomic models are deposited in the European Bioinformatics Institute under accession codes (EMD-1491, 1496, 1497, 1537–1539).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashish Paine MS, Perryman PB, Yang L, Yin HL, Krueger JK. Global structure changes associated with Ca2+ activation of full-length human plasma gelsolin. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25884–25892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702446200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazari WL, Matsudaira P, Wallek M, Smeal T, Jakes R, Ahmed Y. Villin sequence and peptide map identify six homologous domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4986–4990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.4986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bretscher A, Weber K. Villin is a major protein of the microvillus cytoskeleton which binds both G and F actin in a calcium-dependent manner. Cell. 1980;20:839–847. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90330-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess DR, Broschat KO, Hayden JM. Tropomyosin distinguishes between the two actin-binding sites of villin and affects actin-binding properties of other brush border proteins. J Cell Biol. 1987;104:29–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtnick LD, Koepf EK, Grimes J, Jones EY, Stuart DI, McLaughlin PJ, Robinson RC. The crystal structure of plasma gelsolin: implications for actin severing, capping, and nucleation. Cell. 1997;90:661–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80527-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtnick LD, Urosev D, Irobi E, Narayan K, Robinson RC. Structure of the N-terminal half of gelsolin bound to actin: roles in severing, apoptosis and FAF. EMBO J. 2004;23:2713–2722. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JZ, Furst J, Chapman MS, Grigorieff N. Low-resolution structure refinement in electron microscopy. J Struct Biol. 2003;144:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe H, Burtnick LD, Mejillano M, Yin HL, Robinson RC, Choe S. The calcium activation of gelsolin: insights from the 3A structure of the G4-G6/actin complex. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:691–702. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens MM, Bathe M, Frey E, Bausch AR. Actin-binding proteins sensitively mediate F-actin bundle stiffness. Nat Mater. 2006;5:748–753. doi: 10.1038/nmat1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier D, Mandelkow E, Silliman A. Structure of actin-containing filaments from two types of non-muscle cells. J Mol Biol. 1977;113:679–695. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90230-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRosier DJ, Tilney LG. How actin filaments pack into bundles. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1982;46(Pt 2):525–540. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1982.046.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering DS, Matsudaira P. Cysteine scanning mutagenesis at 40 of 76 positions in villin headpiece maps the F-actin binding site and structural features of the domain. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12677–12685. doi: 10.1021/bi9615699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egelman EH, Francis N, DeRosier DJ. F-actin is a helix with a random variable twist. Nature. 1982;298:131–135. doi: 10.1038/298131a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezzell RM, Chafel MM, Matsudaira PT. Differential localization of villin and fimbrin during development of the mouse visceral endoderm and intestinal epithelium. Development. 1989;106:407–419. doi: 10.1242/dev.106.2.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbrizio E, Bonet-Kerrache A, Leger JJ, Mornet D. Actin-dystrophin interface. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10457–10463. doi: 10.1021/bi00090a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feig M, Karanicolas J, Brooks CL., 3rd MMTSB Tool Set: enhanced sampling and multiscale modeling methods for applications in structural biology. J Mol Graph Model. 2004;22:377–395. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrary E, Cohen-Tannoudji M, Pehau-Arnaudet G, Lapillonne A, Athman R, Ruiz T, Boulouha L, El Marjou F, Doye A, Fontaine JJ, et al. In vivo, villin is required for Ca(2+)-dependent F-actin disruption in intestinal brush borders. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:819–830. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.4.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finidori J, Friederich E, Kwiatkowski DJ, Louvard D. In vivo analysis of functional domains from villin and gelsolin. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1145–1155. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.5.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank BS, Vardar D, Chishti AH, McKnight CJ. The NMR structure of dematin headpiece reveals a dynamic loop that is conformationally altered upon phosphorylation at a distal site. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:7909–7916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310524200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friederich E, Vancompernolle K, Louvard D, Vandekerckhove J. Villin function in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton. Correlation of in vivo effects to its biochemical activities in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26751–26760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galkin VE, Orlova A, Cherepanova O, Lebart MC, Egelman EH. High-resolution cryo-EM structure of the F-actin-fimbrin/plastin ABD2 complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1494–1498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708667105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galkin VE, Orlova A, Fattoum A, Walsh MP, Egelman EH. The CH-domain of calponin does not determine the modes of calponin binding to F-actin. J Mol Biol. 2006;359:478–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.03.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenney JR, Jr, Bretscher A, Weber K. Calcium control of the intestinal microvillus cytoskeleton: its implications for the regulation of microfilament organizations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:6458–6462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenney JR, Jr, Geisler N, Kaulfus P, Weber K. Demonstration of at least two different actin-binding sites in villin, a calcium-regulated modulator of F-actin organization. J Biol Chem. 1981;256:8156–8161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesterberg LK, Weber K. Demonstration of three distinct calcium-binding sites in villin, a modulator of actin assembly. J Biol Chem. 1983a;258:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesterberg LK, Weber K. Ligand-induced conformational changes in villin, a calcium-controlled actin-modulating protein. J Biol Chem. 1983b;258:359–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubalek EW, Kornberg RD, Darst SA. Improved transfer of two-dimensional crystals from the air/water interface to specimen support grids for high-resolution analysis by electron microscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 1991;35:295–304. doi: 10.1016/0304-3991(91)90082-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar N, Khurana S. Identification of a functional switch for actin severing by cytoskeletal proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24915–24918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400110200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lebart MC, Mejean C, Boyer M, Roustan C, Benyamin Y. Localization of a new alpha-actinin binding site in the COOH-terminal part of actin sequence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;173:120–126. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebart MC, Mejean C, Roustan C, Benyamin Y. Further characterization of the alpha-actinin-actin interface and comparison with filamin-binding sites on actin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5642–5648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke SJ, Baldwin PR, Chiu W. EMAN: semiautomated software for high-resolution single-particle reconstructions. J Struct Biol. 1999;128:82–97. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1999.4174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus MA, Matsudaira P, Wagner G. Refined structure of villin 14T and a detailed comparison with other actin-severing domains. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1197–1209. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markus MA, Nakayama T, Matsudaira P, Wagner G. Solution structure of villin 14T, a domain conserved among actin-severing proteins. Protein Sci. 1994;3:70–81. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira P, Mandelkow E, Renner W, Hesterberg LK, Weber K. Role of fimbrin and villin in determining the interfilament distances of actin bundles. Nature. 1983;301:209–214. doi: 10.1038/301209a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsudaira PT, Burgess DR. Identification and organization of the components in the isolated microvillus cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol. 1979;83:667–673. doi: 10.1083/jcb.83.3.667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGough A, Chiu W, Way M. Determination of the gelsolin binding site on F-actin: implications for severing and capping. Biophys J. 1998;74:764–772. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)74001-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGough A, Way M, DeRosier D. Determination of the alpha-actinin-binding site on actin filaments by cryoelectron microscopy and image analysis. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:433–443. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.2.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight CJ, Matsudaira PT, Kim PS. NMR structure of the 35-residue villin headpiece subdomain. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:180–184. doi: 10.1038/nsb0397-180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin PJ, Gooch JT, Mannherz HG, Weeds AG. Structure of gelsolin segment 1-actin complex and the mechanism of filament severing. Nature. 1993;364:685–692. doi: 10.1038/364685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng J, Vardar D, Wang Y, Guo HC, Head JF, McKnight CJ. High-resolution crystal structures of villin headpiece and mutants with reduced F-actin binding activity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11963–11973. doi: 10.1021/bi050850x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura N, Asano A. Further characterization of a conserved actin-binding 27-kDa fragment of actinogelin and alpha-actinins and mapping of their binding sites on the actin molecule by chemical cross-linking. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:4717–4723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardee JD, Spudich JA. Purification of muscle actin. Meth Enzymol. 1982;85(Pt B):164–181. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(82)85020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinson KI, Dunbar L, Samuelson L, Gumucio DL. Targeted disruption of the mouse villin gene does not impair the morphogenesis of microvilli. Dev Dyn. 1998;211:109–121. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199801)211:1<109::AID-AJA10>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope B, Way M, Matsudaira PT, Weeds A. Characterisation of the F-actin binding domains of villin: classification of F-actin binding proteins into two groups according to their binding sites on actin. FEBS Lett. 1994;338:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana AP, Ruff P, Maalouf GJ, Speicher DW, Chishti AH. Cloning of human erythroid dematin reveals another member of the villin family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6651–6655. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.14.6651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxton WO, Baumeister W. The correlation averaging of a regularly arranged bacterial cell envelope protein. J Microsc. 1982;127(Pt 2):127–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1982.tb00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T, Kopp J, Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL: An automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3381–3385. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnov SL, Isern NG, Jiang ZG, Hoyt DW, McKnight CJ. The Isolated Sixth Gelsolin Repeat and Headpiece Domain of Villin Bundle F-Actin in the Presence of Calcium and Are Linked by a 40-Residue Unstructured Sequence. Biochemistry. 2007;46:7488–7496. doi: 10.1021/bi700110v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukow C, DeRosier D. How to analyze electron micrographs of rafts of actin filaments crosslinked by actin-binding proteins. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:1039–1050. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KA, Taylor DW. Formation of two-dimensional complexes of F-actin and crosslinking proteins on lipid monolayers: demonstration of unipolar alpha-actinin-F-actin crosslinking. Biophys J. 1994;67:1976–1983. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80680-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney LG, Derosier DJ, Mulroy MJ. The organization of actin filaments in the stereocilia of cochlear hair cells. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:244–259. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.1.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney LG, Egelman EH, DeRosier DJ, Saunder JC. Actin filaments, stereocilia, and hair cells of the bird cochlea. II Packing of actin filaments in the stereocilia and in the cuticular plate and what happens to the organization when the stereocilia are bent. J Cell Biol. 1983;96:822–834. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.3.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney LG, Mooseker M. Actin in the brush-border of epithelial cells of the chicken intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1971;68:2611–2615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.10.2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vardar D, Buckley DA, Frank BS, McKnight CJ. NMR structure of an F-actin-binding “headpiece” motif from villin. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1299–1310. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen W, Vanhaesebrouck P, Van Troys M, Verschueren M, Fant F, Goethals M, Ampe C, Martins JC, Borremans FA. Solution structures of the C-terminal headpiece subdomains of human villin and advillin, evaluation of headpiece F-actin-binding requirements. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1276–1287. doi: 10.1110/ps.03518104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmann N, DeRosier D, Matsudaira P, Hanein D. An atomic model of actin filaments cross-linked by fimbrin and its implications for bundle assembly and function. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:947–956. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way M, Pope B, Weeds AG. Evidence for functional homology in the F-actin binding domains of gelsolin and alpha-actinin: implications for the requirements of severing and capping. J Cell Biol. 1992;119:835–842. doi: 10.1083/jcb.119.4.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler H, Taylor KA. Multivariate statistical analysis of three-dimensional cross-bridge motifs in insect flight muscle. Ultramicroscopy. 1999;77:141–152. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler H, Taylor KA. Accurate marker-free alignment with simultaneous geometry determination and reconstruction of tilt series in electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy. 2006;106:240–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin HL, Stossel TP. Control of cytoplasmic actin gel-sol transformation by gelsolin, a calcium-dependent regulatory protein. Nature. 1979;281:583–586. doi: 10.1038/281583a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.