Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To search for a better dietary approach to treat postprandial lipid abnormalities and improve glucose control in type 2 diabetic patients.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

According to a randomized crossover design, 18 type 2 diabetic patients (aged 59 ± 5 years; BMI 27 ± 3 kg/m2) (means ± SD) in satisfactory blood glucose control on diet or diet plus metformin followed a diet relatively rich in carbohydrates (52% total energy), rich in fiber (28g/1,000 kcal), and with a low glycemic index (58%) (high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet) or a diet relatively low in carbohydrate (45%) and rich in monounsaturated fat (23%) (low-carbohydrate/high–monounsaturated fat diet) for 4 weeks. Thereafter, they shifted to the other diet for 4 more weeks. At the end of each period, plasma glucose, insulin, lipids, and lipoprotein fractions (separated by discontinuous density gradient ultracentrifugation) were determined on blood samples taken at fasting and over 6 h after a test meal having a similar composition as the corresponding diet.

RESULTS

In addition to a significant decrease in postprandial plasma glucose, insulin responses, and glycemic variability, the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet also significantly improved the primary end point, since it reduced the postprandial incremental areas under the curve (IAUCs) of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, in particular, chylomicrons (cholesterol IAUC: 0.05 ± 0.01 vs. 0.08 ± 0.02 mmol/l per 6 h; triglycerides IAUC: 0.71 ± 0.35 vs. 1.03 ± 0.58 mmol/l per 6 h, P < 0.05).

CONCLUSIONS

A diet rich in carbohydrate and fiber, essentially based on legumes, vegetables, fruits, and whole cereals, may be particularly useful for treating diabetic patients because of its multiple effects on different cardiovascular risk factors, including postprandial lipids abnormalities.

The clinical and scientific relevance of postprandial lipid abnormalities is based on the evidence of their association with a higher cardiovascular risk as recently shown by the results of two large prospective studies (1,2). Patients with type 2 diabetes have more pronounced postprandial dyslipidemia (3,4), and this may account, at least in part, for their higher rate of cardiovascular diseases, not explained by hyperglycemia and the classic cardiovascular risk factors alone (5).

Despite the clinical relevance of postprandial lipid alterations, there is little scientific evidence on the potential therapeutic interventions able to correct these abnormalities. If we consider that humans spend most of their time in the postprandial condition and that all the lipid alterations in this state greatly outnumber those occurring in fasting conditions, diet is the natural approach to correct postprandial abnormalities. However, while it has been repeatedly demonstrated that dietary treatment in type 2 diabetic patients is able to improve glucose control and blood lipids at fasting (6), there are few data on the effects of various diets on postprandial lipemia (7). The Mediterranean diet is generally recommended as a useful nutritional tool for the prevention of cardiovascular disease because it is able to act positively on the main cardiovascular risk factors, including excess body weight (8). However, the two main components of the Mediterranean diet—olive oil rich in monounsaturated fat and foods rich in carbohydrate and fiber—traditionally found in association in the Mediterranean diet of some decades ago are now often considered in opposition. In particular, a diet rich in carbohydrate is considered less effective on fasting lipid metabolism than one rich in monounsaturated fat (MUFA), as it induces higher plasma triglycerides concentrations (22%) and lower HDL cholesterol levels (4%) (9); these untoward effects, however, can be avoided by selecting carbohydrate rich foods with high fiber content and a low glycemic index (10).

It can be hypothesized that a diet containing these kinds of foods may be more beneficial on postprandial lipid metabolism compared with a MUFA-rich diet, which, given the higher fat content, could induce a postprandial increase in triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, especially of exogenous origin.

On the basis of this working hypothesis, the aim of this intervention study was to evaluate in type 2 diabetic patients the effects on postprandial lipemia and glucose metabolism (both in everyday life conditions and after a standard test meal) of two diets—one moderately rich in carbohydrate, rich in fiber, and with a low glycemic index and the other relatively low in carbohydrate and rich in MUFA.

Because adipose tissue, mainly through its lipolytic activities, is considered as having a pivotal role in the buffering of lipid flux in the postprandial period (11), a further goal of our study was to evaluate the activities of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) after consumption of the two diets as possible mechanisms of different effects on postprandial lipid metabolism.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

A total of 19 type 2 diabetic patients were enrolled in the study, after giving their written informed consent. There was one dropout because of concomitant family problems; therefore, 12 men and 6 women, aged 59 ± 5 years (means ± SD), concluded the study. Patients were slightly overweight (BMI 27 ± 3 kg/m2), in satisfactory blood glucose control (A1C 6.9 ± 0.7%) on diet alone (n = 13) or diet plus metformin (n = 5), and with normal fasting plasma lipid levels. They were all sedentary and did not change their physical activity level throughout the study. The protocol was approved by the Federico II University Ethics Committee.

Sample size

Based on differences in the postprandial responses of triglycerides in the chylomicrons and VLDL fractions between diabetic and control subjects (0.7 mmol/l per 6 h, SD 0.85 mmol/l) (12), we considered as clinically relevant a 30% difference between the two treatments of the primary end point (postprandial incremental area of triglycerides content in chylomicrons and VLDL fraction). To detect this difference with an 80% power at a P value of 5% (two-tailed), 13 patients had to be studied.

Study design

The study was performed according to a randomized crossover design. After a run-in period of 4 weeks, during which patients were stabilized on their own diet, they followed, in alternate order, two isoenergetic diets, each for 4 weeks. One diet was relatively rich in carbohydrate, rich in dietary fiber both of soluble and insoluble type, and with a low glycemic index; the other was rich in MUFA, relatively low in carbohydrate, low in dietary fiber, and with a relatively high glycemic index (Table 1). The glycemic load of the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet was lower than that of the high-MUFA diet (155 vs. 205). The other components of the two diets, in particular, the saturated fat content, were similar (Table 1). Calories and nutrients of the diets were calculated from tables of food composition of the Italian Institute of Nutrition using the MetaDieta software (Meteda s.r.l., Ascoli-Piceno, Italy). The main components of the two diets were as follows: 1) a portion of legumes four times a week, one serving of pasta twice a week, and one serving of parboiled rice once a week; two servings of vegetables and two fruits per day; and whole-grain bread for the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet and 2) white bread, a serving of potatoes, rice, or pasta each twice weekly; a serving of pizza once a week; and use of vegetables and fruits low in fiber for the low-carbohydrate diet (a weekly meal schedule for both dietary treatments is shown in an online appendix, Tables S1 and S2, available at http://care.diabetesjournals.org/cgi/content/full/dc09-0266/DC1).

Table 1.

Composition of the two isoenergetic diets recommended and followed by the patients

| High-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet |

Low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA diet |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended | Followed | Recommended | Followed | |

| Total energy (kcal/day) | 1,918 | 1,874 ± 315 | 1,939 | 1,862 ± 348 |

| Proteins (%) | 18 | 18 ± 1 | 18 | 18 ± 1 |

| Total fat (%) | 30 | 30 ± 1* | 37 | 37 ± 1 |

| Saturated fat (%) | 7 | 7 ± 1 | 7 | 7 ± 1 |

| MUFA (%) | 17 | 17 ± 1* | 23 | 23 ± 1 |

| Polyunsaturated n-6 fat (%) | 3.9 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 4.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 |

| Cholesterol (g/day) | 143 | 133 ± 43 | 158 | 160 ± 32 |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 52 | 51 ± 1* | 45 | 44 ± 1 |

| Starch (%) | 41 | 39 ± 1* | 35 | 34 ± 1 |

| Soluble (%) | 10.5 | 12 ± 1 | 10.1 | 10 ± 1 |

| Fiber (g/1,000 kcal) | 28 | 27 ± 2* | 8 | 8 ± 1 |

| Glycemic index (%) | 58 | 60 ± 4* | 88 | 87 ± 2 |

| Glycemic load | 155 | 154 ± 24* | 205 | 207 ± 37 |

Data are means ± SD.

*P < 0.05 vs. low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA diet.

To improve dietary compliance, patients were seen weekly by an experienced dietitian who, in addition, called them every 2–3 days to ensure that they followed the diet assigned. Adherence to the two dietary treatments was evaluated by a 3-day food record filled in by the patients at the end of the two periods.

Experimental procedures

At the end of each dietary intervention period, patients underwent the following procedures: 1) 12-h fasting blood sampling for the determination of total, LDL, and HDL cholesterol and triglycerides; 2) home self-measurement of triglyceride and glucose levels with samples taken at fasting, immediately before, and 2 and 3 h after lunch and before dinner for 2 days at the end of each dietary treatment; and 3) a test meal with a composition similar to the dietary treatment being followed, with blood samples taken at fasting (at least 12 h) and 2, 4, and 6 h after the meal to evaluate glucose, insulin, cholesterol, and triglycerides in plasma and lipoprotein subfractions. The test meal was performed in 12 patients. The composition of the test meal performed at the end of the high-fiber diet was 52% carbohydrate (41% starch, 11% soluble), 30% fat (7% saturated), and 18% protein and consisted of beans and pasta soup plus an apple. The composition of the test meal performed at the end of the low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA diet was 45% carbohydrate (34% starch, 11% soluble), 37% fat (7% saturated), and 18% protein and consisted of a potato gateau (a pie made of mashed potato, whole milk, eggs, cheese, ham, and butter) plus orange juice. The energy content of the two test meals was 948 kcal. 4) Six hours after the test meal, a needle biopsy of abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue was taken for the determination of LPL and HSL activities.

Laboratory procedures

All laboratory measurements were made blind to the dietary treatments.

Lipoprotein separation.

Samples were kept at 4°C before, during, and after centrifugation. Fasting and postprandial lipoprotein subfractions were isolated by discontinuous density gradient ultracentrifugation, as previously described (5). Briefly, three consecutive runs were performed at 15°C and at 40,000 rpm to float chylomicrons (Svedberg flotation unit [Sf] >400), large VLDL (Sf 60–400), and small VLDL (Sf 20–60). Intermediate-density lipoproteins (Sf 12–20) and LDLs (Sf 0–12) were recovered from the gradient after the Sf 20–60 particles had been collected. HDLs were isolated by a precipitation method.

Adipose tissue lipases activities.

Heparin-releasable LPL, total LPL, and HSL activities were determined as previously described (13).

Other measurements.

Cholesterol and triglyceride concentrations were assayed by enzymatic colorimetric methods; plasma insulin concentrations were acquired by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Home self-measurements of triglyceride levels were performed by a GCT Accutrend instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany), a method already validated (3).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± SD unless otherwise stated. Postprandial incremental areas were calculated by the trapezoidal method as the area under the curve above the baseline value (IAUC). Coefficients of variations of plasma glucose at different points after test meals were evaluated as an index of postprandial glycemic variability (14). Differences between the two diets were evaluated by ANOVA for repeated measures and t test for paired data. Two-tailed tests were used, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Variables not normally distributed were analyzed after logarithmic transformation or by nonparametric tests.

Because there was no carry-over effect, the results of patients starting with either diet were put together. The statistical analysis was performed according to standard methods using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences software (SPSS/PC; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

There were no changes in body weight during the experiment (73.0 kg after both dietary treatments). The compliance to the two diets was optimal, as shown by the average composition of the diet followed by subjects (Table 1). As expected, the two diets followed by patients were significantly different for total fat, MUFA, carbohydrate, fiber, glycemic index, and glycemic load (Table 1). Both diets were well accepted by patients.

Fasting plasma lipoproteins

At the end of the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet, there was a significant reduction of total cholesterol (4.20 ± 0.70 vs. 4.40 ± 0.78 mmol/l, P < 0.05), LDL cholesterol (2.62 ± 0.60 vs. 2.82 ± 0.62 mmol/l, P < 0.05), and HDL cholesterol (0.98 ± 0.25 vs. 1.06 ± 0.26 mmol/l, P < 0.05) and an increase in HDL triglycerides (0.20 ± 0.05 vs. 0.18 ± 0.05 mmol/l, P < 0.05) in comparison with the low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA diet, whereas triglyceride levels in plasma (1.16 ± 0.38 vs. 1.07 ± 0.39 mmol/l) and LDL (0.41 ± 0.11 vs. 0.41 ± 0.09 mmol/l) were similar.

Home self-monitoring

Blood glucose levels measured by patients (average of two daily profiles) were significantly lower during the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet both 2 h (7.2 ± 1.1 vs. 9.2 ± 2.9 mmol/l; P < 0.05) and 3 h (5.9 ± 1.3 vs. 7.3 ± 1.5 mmol/l; P < 0.05) after lunch. Similarly, self-monitored triglyceride levels (average of two daily profiles) were 30% lower 3 h after lunch.

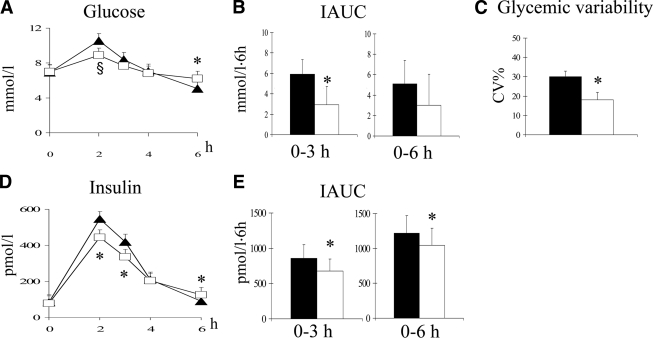

Plasma glucose and insulin responses to test meals

After the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber test meal, performed at the end of the corresponding diet, plasma glucose concentrations were lower in the first part of the postprandial curve, especially after 2 h (P = 0.06) (Fig. 1A). The same pattern was observed for plasma insulin, significantly lower at the second and third hour (P < 0.05 for both) than after the low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA test meal performed at the end of the corresponding diet (Fig. 1D). ANOVA for repeated measures was statistically significant for plasma glucose (P < 0.05) and plasma insulin curves (P < 0.008). The combination of the effects on plasma glucose and insulin led to a reduction of the insulin-to-glucose ratio both at the second (0.44 ± 0.30 vs. 0.52 ± 0.46) and third hour (0.39 ± 0.29 vs. 0.49 ± 0.34; P < 0.05) after the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber test meal. On the contrary, plasma glucose and insulin levels were both significantly higher 6 h after the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber meal than after the other test meal (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1A and D). These patterns in the postprandial curve corresponded to 1) a nearly 50% decrease in plasma glucose IAUC until the third hour (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1B); 2) a significant reduction in insulin IAUC by 14 and 21%, at 3 and 6 h, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1E); and 3) a significant decrease of nearly 50% in postprandial glycemic variability (P < 0.02) (Fig. 1C).

Figure 1.

Plasma glucose and insulin curves (A and D), plasma glucose and IAUC (B and E), and glycemic variability (C) after a high-carbohydrate/high-fiber test meal (white squares and white bars) or a low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA test meal (▴, ■) performed at the end of the corresponding diet (means ± SE, significance for paired t test: *P < 0.05, §P = 0.06; significance for repeated measures ANOVA: P < 0.05 for plasma glucose and P < 0.008 for plasma insulin).

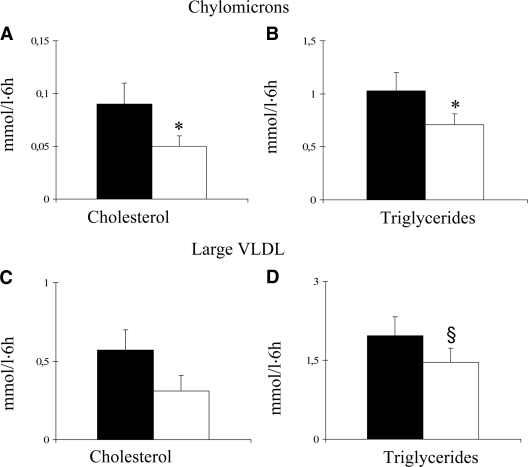

Plasma lipid and lipoprotein responses to test meals

At the end of the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet, postprandial IAUC of plasma triglycerides decreased by 31% compared with the low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA diet (1.87 ± 1.22 vs. 2.70 ± 1.58 mmol/l per 6 h), whereas no significant differences were observed for plasma cholesterol IAUC. In terms of peak postprandial changes, the 4-h increments were 0.4 ± 0.3 mmol/l for the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet and 0.6 ± 0.4 mmol/l for the other diet (P < 0.05).

The postprandial responses of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins are reported in Fig. 2. Both triglycerides and cholesterol in chylomicrons were lower after the test meal performed at the end of the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet, and the IAUC was significantly reduced by 31 and 46%, respectively (P < 0.05 for both) (Fig. 2A and B). Similarly reduced was the triglyceride content of large VLDL (IAUC 1.46 ± 0.94 vs. 1.97 ± 1.22 mmol/l per 6 h, P < 0.06) (Fig. 2D), small VLDL (IAUC −0.21 ± 0.24 vs. −0.15 ± 0.21 mmol/l per 6 h, P = 0.07), and LDL (IAUC −0.05 ± 0.06 vs. 0.17 ± 0.05 mmol/l per 6 h, P < 0.05). No differences were observed in the postprandial response of the other lipoproteins (data not shown).

Figure 2.

IAUC for cholesterol and triglycerides in chylomicrons (A and B) and large VLDL (C and D) after a high-carbohydrate/high-fiber test meal (□) or a low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA test meal (■) performed at the end of the corresponding diet (means ± SE, *P < 0.05, §P = 0.06).

Lipases activities

Both total and heparin-releasable LPL activities in adipose tissue were not significantly different at the end of the two diets (total LPL activity: 2,792 ± 958 vs. 3,375 ± 2,251 nmol fatty acid per gram per hour; heparin releasable LPL activity: 146 ± 70 vs. 184 ± 117 nmol fatty acid per gram per hour). Likewise, no difference was observed in HSL activity (616 ± 237 vs. 676 ± 210 nmol fatty acid per gram per hour).

CONCLUSIONS

This study clearly shows, for the first time, that a diet moderately rich in carbohydrate, rich in dietary fiber, and, consequently, with low glycemic index and glycemic load, essentially based on consumption of legumes, vegetables, fruits, and whole cereals, induces a significant reduction of postprandial lipoproteins, particularly chylomicrons, in type 2 diabetic patients. This effect was observed in experimental conditions, i.e., after a standard test meal, but also in everyday life, where there was a 30% reduction of plasma triglycerides 3 h after lunch, despite the well-known high day-to-day triglyceride variability (20% in our data).

Moreover, our results confirm that this kind of diet is to be preferred to a diet low in carbohydrate and rich in MUFA for its effects on:

1) Postprandial blood glucose control, with lower peaks in the first part of the postprandial period. This blunted postprandial profile implies a reduced variability of blood glucose levels (almost halved in our study), considered so important in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in diabetic patients (15), as well as a lower risk of late postprandial hypoglycemia (16).

2) Postprandial insulin levels, which are significantly reduced concomitantly with the presence of lower blood glucose levels, suggesting an improvement in insulin action.

3) LDL cholesterol levels, significantly reduced also in normocholesterolemic type 2 diabetic patients, reinforcing the data already obtained in patients with higher LDL cholesterol levels (10). This result, which may be considered of small entity (a 9% reduction), is, instead, important from a clinical point of view considering the need to constantly lower LDL cholesterol values, especially in type 2 diabetic patients (6).

The only drawback of the diet rich in carbohydrate and fiber is the lower levels of fasting HDL cholesterol obtained compared with the diet low in carbohydrate and rich in MUFAs. Moreover, it is important to underline that any intervention able to reduce LDL cholesterol levels generally leads also to a reduction in HDL cholesterol. Furthermore, a previous study has shown that the decrease in HDL cholesterol after a low-fat/high-carbohydrate diet is limited to HDL3 (17), which is the HDL subfraction with less antiatherogenic properties.

Our results emphasize the clear importance of the quality of carbohydrate, beside that of their amount (18). Indeed, the few studies that have so far looked at the effects of high-carbohydrate versus high-MUFA diets on postprandial lipid metabolism compared diets rich in MUFA with diets rich in carbohydrate, but not in dietary fiber, and with a low glycemic index (19–21).

How can the two dietary approaches act on the postprandial response of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins? We looked at the possible effects of the two diets on lipolysis in adipose tissue, considering the crucial role of this tissue in partitioning the postprandial lipids (11). However, both LPL and HSL activities were not different at the end of either diet. This suggests that the two diets might act on other sites, particularly on those involved in the absorption of dietary fatty acids and cholesterol and the production of chylomicrons and VLDL, not only through their nutrient composition but also for their different combination of foods and for the presence of other components. On the one hand, since low-carbohydrate/high-MUFA diets are richer in the amount of fat, which is one of the main determinants of postprandial lipid response (22), they may induce a higher absorption of dietary fatty acids, which would result in a higher intestinal production of chylomicrons. On the other hand, since the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet is at the same time rich in carbohydrate and dietary fiber, it may act in different ways, i.e., by slowing down gastric empting; reducing the absorption of glucose, cholesterol, and fatty acids; and, finally, reducing the intestinal production and secretion of chylomicrons, as suggested by studies performed both in vitro and in vivo (23). Moreover, since the high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet also reduces postprandial plasma glucose and insulin, it is likely that both effects may reduce de novo lipogenesis, which is stimulated by glucose and insulin levels (23) and may be particularly relevant in type 2 diabetic patients, where it accounts for 25% of VLDL synthesis (24). Moreover, our high-carbohydrate diet, being rich in fiber, also induced an improvement in insulin resistance, as suggested by the lower insulin-to-glucose ratios, which is relevant given the well-known key role played by insulin resistance in determining postprandial lipoprotein abnormalities (25).

Clinical relevance of our results lies on the fact that postprandial lipemia is, according to recent prospective studies (1,2), an independent cardiovascular risk factor. On the basis of these studies, a difference in postprandial triglycerides of 0.25 mmol/l such as that observed between our two diets could mean a reduction in cardiovascular risk of ∼25%. It has to be underlined that our results have been obtained with a nonpharmacological intervention comparing two diets both recommended and in individuals with quite low lipid levels.

Limitations

Participants in our study were type 2 diabetic patients in relatively good blood glucose control, with quite normal plasma lipid levels, who already used a diet relatively rich in carbohydrate and fiber. Therefore, we cannot extrapolate our results to all type 2 diabetic patients. However, it has to be considered that a similar type of high-carbohydrate/high-fiber diet induced similar, if not better, results on blood glucose control and fasting lipid metabolism in type 2 diabetic patients not in satisfactory blood glucose control and with hyperlipidemia (10,18). Another point to be stressed is the length of the intervention: although 1 month for each diet cannot be considered a long-term experiment, it is certainly sufficiently long enough to induce changes in glucose and lipid metabolism.

In conclusion, a diet relatively high in carbohydrates, rich in dietary fiber, with a relatively low glycemic index and a low glycemic load, essentially based on consumption of legumes, vegetables, fruit, and whole cereals, may be particularly useful for the treatment of type 2 diabetic patients on the basis of its multiple effects on different cardiovascular risk factors, including postprandial lipid abnormalities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from “Regione Campania” (L.R. n.5/2002).

Accutrend instrument and triglycerides strips were supplied by Roche Diagnostics (Mannheim, Germany). No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

The excellent technical laboratory assistance of P. Cipriano is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are grateful to R. Scala for expert linguistic revision.

Footnotes

Clinical trial reg. no. NCT00789295, clinicaltrials.gov.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

References

- 1. Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A: Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA 2007; 298: 299– 308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bansal S, Buring JE, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks FM, Ridker PM: Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA 2007; 298: 309– 316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iovine C, Vaccaro O, Gentile A, Romano G, Pisanti F, Riccardi G, Rivellese AA: Post-prandial triglyceride profile in a population-based sample of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetologia 2004; 47: 19– 22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pastromas S, Terzi AB, Tousoulis D, Koulouris S: Postprandial lipemia: an under-recognized atherogenic factor in patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Cardiol 2008; 126: 3– 12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rivellese AA, De Natale C, Di Marino L, Patti L, Iovine C, Coppola S, Del Prato S, Riccardi G, Annuzzi G: Exogenous and endogenous postprandial lipid abnormalities in type 2 diabetic patients with optimal blood glucose control and optimal fasting triglyceride levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004; 89: 2153– 2159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nutrition Recommendations and Interventions for Diabetes: A position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008; 31: S61– S78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lopez-Miranda J, Williams C, Lairon D: Dietary, physiological, genetic and pathological influences on postprandial lipid metabolism. Br J Nutr 2007; 98: 458– 473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, Golan R, Fraser D, Bolotin A, Vardi H, Tangi-Rozental O, Zuk-Ramot R, Sarusi B, Brickner D, Schwartz Z, Sheiner E, Marko R, Katorza E, Thiery J, Fiedler GM, Blüher M, Stumvoll M, Stampfer MJ: Dietary Intervention Randomized Controlled Trial (DIRECT) Group. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med 2008; 359: 229– 241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Garg A: High-monounsaturated-fat diets for patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 1998; 67: 577S– 582S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Riccardi G, Rivellese AA: Effects of dietary fiber and carbohydrate on glucose and lipoprotein metabolism in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 1991; 14: 1115– 1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Frayn KN: Adipose tissue as a buffer for daily lipid flux. Diabetologia 2002; 45: 1201– 1210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Annuzzi G, Giacco R, Patti L, Di Marino L, De Natale C, Costabile G, Marra M, Santangelo C, Masella R, Rivellese AA: Postprandial chylomicrons and adipose tissue lipoprotein lipase are altered in type 2 diabetes independently of obesity and whole-body insulin resistance. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2008; 18: 531– 538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rivellese AA, Giacco R, Annuzzi G, De Natale C, Patti L, Di Marino L, Minerva V, Costabile G, Santangelo C, Masella R, Riccardi G: Effects of monounsaturated vs. saturated fat on postprandial lipemia and adipose tissue lipases in type 2 diabetes. Clin Nutr 2008; 27: 133– 141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muggeo M, Zoppini G, Bonora E, Brun E, Bonadonna RC, Moghetti P, Verlato G: Fasting plasma glucose variability predicts 10-years survival of type 2 diabetic patients. The Verona Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 45– 50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Keefe JH, Bell DS: Postprandial hyperglycemia/hyperlipidemia (postprandial dysmetabolism) is a cardiovascular risk factor. Am J Cardiol 2007; 100: 899– 904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Giacco R, Parillo M, Rivellese AA, Lasorella G, Giacco A, D'Episcopo L, Riccardi G: Long-term dietary treatment with increased amounts of fiber-rich low-glycemic index natural foods improves blood glucose control and reduces the number of hypoglycemic events in type 1 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2000; 23: 1461– 1466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Desroches S, Paradis ME, Pérusse M, Archer WR, Bergeron J, Couture P, Bergeron N, Lamarche B: Apolipoprotein A-I, A-II, and VLDL-B-100 metabolism in men: comparison of a low-fat diet and a high-monounsaturated fatty acid diet. J Lipid Res 2004; 45: 2331– 2338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Riccardi G, Rivellese AA, Giacco R: Role of glycemic index and glycemic load in the healthy state, in prediabetes, and in diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87: 269S– 274S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berglund L, Lefevre M, Ginsberg HN, Kris-Etherton PM, Elmer PJ, Stewart PW, Ershow A, Pearson TA, Dennis BH, Roheim PS, Ramakrishnan R, Reed R, Stewart K, Phillips KM: DELTA Investigators. Comparison of monounsaturated fat with carbohydrates as a replacement for saturated fat in subjects with a high metabolic risk profile: studies in the fasting and postprandial states. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86: 1611– 1620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paniagua JA, de la Sacristana AG, Sánchez E, Romero I, Vidal-Puig A, Berral FJ, Escribano A, Moyano MJ, Peréz-Martinez P, López-Miranda J, Pérez-Jiménez F: A MUFA-rich diet improves posprandial glucose, lipid and GLP-1 responses in insulin-resistant subjects. J Am Coll Nutr 2007; 26: 434– 444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Lamendola C, Yeni-Komshian H, Reaven G: Carbohydrate-induced hypertriglyceridemia: an insight into the link between plasma insulin and triglyceride concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000; 85: 3085– 3088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dubois C, Beaumier G, Juhel C, Armand M, Portugal H, Pauli AM, Borel P, Latgé C, Lairon D: Effects of graded amounts (0–50 g) of dietary fat on postprandial lipemia and lipoproteins in normolipidemic adults. Am J Clin Nutr 1998; 67: 31– 38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lairon D, Play B, Jourdheuil-Rahmani D: Digestible and indigestible carbohydrates: interactions with postprandial lipid metabolism. J Nutr Biochem 2007; 18: 217– 227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts R, Bickerton AS, Fielding BA, Blaak EE, Wagenmakers AJ, Chong MF, Gilbert M, Karpe F, Frayn KN: Reduced oxidation of dietary fat after a short term high-carbohydrate diet. Am J Clin Nutr 2008; 87: 824– 831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adiels M, Taskinen MR, Borén J: Fatty liver, insulin resistance, and dyslipidemia. Curr Diab Rep 2008; 8: 60– 64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.