Abstract

Background: Global DNA hypomethylation may result in chromosomal instability and oncogene activation, and as a surrogate of systemic methylation activity, may be associated with breast cancer risk. Methods: Samples and data were obtained from women with incident early-stage breast cancer (I–IIIa) and women who were cancer free, frequency matched on age and race. In preliminary analyses, genomic methylation of leukocyte DNA was determined by measuring 5-methyldeoxycytosine (5-mdC), as well as methylation analysis of the LINE-1-repetitive DNA element. Further analyses used only 5-mdC levels. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for risk of breast cancer in relation to amounts of methylation. Results: In a subset of samples tested (n = 37), 5-mdC level was not correlated with LINE-1 methylation. 5-mdC level in leukocyte DNA was significantly lower in breast cancer cases than healthy controls (P = 0.001), but no significant case–control differences were observed with LINE-1 methylation (P = 0.176). In the entire data set, we noted significant differences in 5-mdC levels in leukocytes between cases (n = 176) and controls (n = 173); P value < 0.001. Compared with women in the highest 5-mdC tertile (T3), women in the second (T2; OR = 1.49, 95% CI = 0.84–2.65) and lowest tertile (T1; OR = 2.86, 95% CI = 1.65–4.94) had higher risk of breast cancer (P for trend ≤0.001). Among controls only and cases and controls combined, only alcohol intake was found to be inversely associated with methylation levels. Conclusion: These findings suggest that leukocyte DNA hypomethylation is independently associated with development of breast cancer.

Introduction

Alterations of DNA methylation, which influence gene expression and genome integrity, are an important component of cancer development (1). Although localized hypomethylation and hypermethylation of specific genes has been studied more extensively, global DNA hypomethylation is a hallmark of most cancer genomes (2–6), including breast cancer (7–11). Hypomethylation has been proposed to contribute to malignancy by activating oncogenes (12,13), inducing genomic instability (14) and causing chromosome instability (4,15–17).

To date, the majority of methylation studies have used DNA obtained from tumor tissues (2,18), with assessment of differences in methylation levels between tumor and histologically normal tissue, for identification of methylation markers (18–20). However, the invasiveness of obtaining tumor tissue and the probable existence of tissue heterogeneity limits the utility of this approach for epidemiologic studies. Recently, global hypomethylation in peripheral blood DNA was noted as an independent risk factor of colorectal, bladder and head and neck cancer (21–24), presumably causing genomic instability among systemic cells for tumor development (25). Thus, leukocyte DNA may be a potential surrogate biomarker for systemic genome methylation status.

Genome-wide DNA hypomethylation derives from the overall level of 5-methyldeoxycytosine (5-mdC) in dinucleotide CpG sites in the genome. Since most 5-mdC sites are located in repetitive sequences that constitute about half of the human genome, and those repetitive DNA sequences are heavily methylated in normal tissue (4,26,27), methylation of LINE-1, one of the most prevalent repetitive sequences, has been used as a surrogate marker for genomic methylation levels (28).

In the present study, we first used both 5-mdC and LINE-1 methodologies to measure methylation levels of blood DNA in a subset of 19 breast cancer cases and 18 controls. Based upon results from the pilot study, the 5-mdC method was subsequently used in 179 breast cancer cases and 180 controls to investigate whether genomic methylation in leukocyte DNA, as a surrogate of systemic methylation activity, was associated with breast cancer risk. Demographic and lifestyle factors were considered as potential determinants of methylation levels and as potential effect modifiers of putative associations between methylation levels and breast cancer risk.

Materials and methods

Study population

Data and samples were obtained from the Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) Databank and Biorepository (DBBR), a shared Core resource (29). In the DBBR, patients newly diagnosed with cancer consent to provide a blood sample and to complete an in-depth epidemiologic questionnaire that includes a food frequency questionnaire, information on reproductive history, family history of cancer, supplement use, comorbidities, prescription and non-prescription medication use, smoking, alcohol consumption, lifetime physical activity, height and weight from young adulthood to present and demographic factors. Permission is granted for linkage of data and samples with medical record information and for use by investigators with protocols approved by the RPCI Institutional Review Board. Visitors and family members of patients are consented as healthy controls, who can be matched by sex, age, residence and race for patients with other types of cancers. Relationships with patients are noted so that they are not included in the same population, avoiding overmatching. Blood samples are drawn prior to surgery or chemotherapy and processed and frozen within 1 h of phlebotomy. This study of hypomethylation and breast cancer risk was approved by the RPCI Institutional Review Board.

Study participants

For these analyses, we obtained DNA and data from the DBBR from patients with early stage (I, II and IIIa) histologically confirmed breast cancer, ages 35–75. Controls were free of malignant diseases, with the exception of non-melanoma skin cancer, and were frequency matched to cases on age and race. DNA was extracted from whole blood using Flexigene kits and was stored at −70°C until analysis. For these analyses, we requested data and samples from 179 cases, who met the above eligibility criteria, and 180 matched controls.

Global genomic DNA methylation analysis

5-mdC levels were determined by liquid chromatography–electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry after hydrolysis of DNA (1 μg) as described previously (30). Briefly, global DNA methylation was expressed as the ratio of 5-mdC to guanine and was determined directly using guanine as the internal standard based on the assumption that (guanine) = (5-mdC) + (cytosine). Methylated and unmethylated DNA from colorectal cancer cell line HCT116 and DKO, which lacks both DNA methyltransferases DNMT1 and DNMT3b in HCT116, was run in every batch as quality control to standardize between batches by adjusting the difference of methylation level of quality control. All analyses were done on duplicate samples. Mean coefficient of variation within 37 subjects was 4.9%.

Quantitative bisulfite pyrosequencing

The methylation status of LINE-1-repetitive DNA element was analyzed using quantitative pyrosequencing of sodium bisulfite-converted DNA (31). Primers, polymerase chain reaction cycling conditions and materials were described previously (32). Non-CpG cytosines served as internal controls to verify efficient sodium bisulfite DNA conversion, and methylated and unmethylated DNAs were also run as controls. Pyrosequencing was done on duplicate samples and pyrosequencing assays were performed a minimum of two times.

Statistical analysis

Global methylation levels measured by 5-mdC and LINE-1, which were normally distributed, were compared using general linear model in 37 samples (19 cases and 18 controls). In the full study population, after standardization between batches and exclusion of 1% outliers of 5-mdC distribution, 5-mdC levels were normally distributed in both cases (n = 176) and controls (n = 173) assessed by skew and kurtosis test. Continuous variables and amounts of global methylation were categorized into dichotomous or tertiled variables based on the distribution among controls. Chi-square test for categorical variables was used to compare characteristics between cases and controls. To identify potential predictors of methylation levels and/or factors that may modify the association between methylation levels and breast cancer risk, univariate associations between DNA methylation and each lifestyle or demographic factor were assessed among controls and among all participants after adjustment for case–control status. Age, body mass index, pack-years of tobacco use, frequency of alcohol intake and parity were assessed as both continuous and categorical variables. Relationships between methylation levels and demographic and lifestyle variables were assessed using standardized β-coefficients. For body mass index, pack-years of tobacco use, frequency of alcohol intake and parity, categorical variables were entered as continuous variables 0, 1, 2 to determine standardized β-coefficients. Logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between genomic methylation levels and breast cancer risk. For potential confounding, we examined known risk factors for breast cancer, i.e. age (categorical variable, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69 and 70+), race (Caucasian and African-American), family history of breast cancer (yes and no), menopausal status (premenopausal and postmenopausal), body mass index (<25, 25–29.9 and 30+), smoking habit (never and ever), pack-years (never smoker, below median and at or above median), alcohol consumption (never and ever), alcohol consumption frequency (never drinking, below median and at or above median), age at menarche (<13 and 13+), age at first birth (<25, 25+ and nulliparous), parity (1–2 children, 3+ and nulliparous) and multivitamin use (never or occasionally and regularly) (shown in Table I), variables reported to affect methylation in the literature (age and race) (22,33–36), variables associated with methylation in the data set (frequency of alcohol consumption) and laboratory variability (batches). While none of the variables assessed changed OR estimates by at least 10%, age, race and batch were kept in all final models. Unordered polychotomous logistic regression models were used to compare different subtype of breast cancer cases. Linear trends for categorical variables were assessed by a two-sided likelihood ratio test. Potential interactions were evaluated using cross-product terms and likelihood ratio test statistics comparing models with and without the cross-product term.

Table I.

Characteristics of breast cancer cases and controls, RPCI, DBBR, 2004–2007 (Controls matched on age and races)

| Cases, N = 179 | Controls, N = 180 | P valuea | OR (95% CI)b | |

| Age | ||||

| 30–39 | 6 (3.4) | 8 (4.4) | ||

| 40–49 | 43 (24.0) | 42 (23.3) | ||

| 50–59 | 55 (30.7) | 65 (36.1) | ||

| 60–69 | 54 (30.2) | 47 (26.1) | ||

| 70+ | 21 (11.7) | 18 (10.0) | P = 0.764 | |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 168 (93.9) | 170 (94.4) | 1.00 | |

| African-American | 11 (6.2) | 10 (5.6) | P = 0.812 | 0.91 (0.91–2.21) |

| Family history of BRCA | ||||

| No | 122 (68.2) | 142 (78.9) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 29 (16.2) | 37 (20.6) | P = 0.740 | 0.89 (0.51–1.54) |

| Missing | 28 (15.6) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | 59 (33.0) | 73 (40.6) | 1.00 | |

| Postmenopausal | 90 (50.3) | 102 (56.7) | P = 0.699 | 1.00 (0.51–1.98) |

| Missing | 30 (16.8) | 5 (2.8) | ||

| Education | ||||

| Below or at high school | 41 (22.9) | 36 (20.0) | 1.00 | |

| Above high school | 107 (59.8) | 143 (79.4) | P = 0.107 | 0.66 (0.39–1.12) |

| Missing | 31 (17.3) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| BMI | ||||

| <25 | 47 (26.3) | 52 (28.9) | 1.00 | |

| 25–29.9 | 43 (24.0) | 63 (35.0) | 0.74 (0.43–1.30) | |

| 30+ | 55 (30.7) | 49 (27.2) | P = 0.200 | 1.27 (0.73–2.24) |

| Missing | 34 (19.0) | 16 (8.9) | ||

| Smoking habit | ||||

| Never | 75 (41.9) | 85 (47.2) | 1.00 | |

| Ever | 74 (41.3) | 87 (58.3) | P = 0.870 | 0.94 (0.61–1.47) |

| Missing | 30 (16.8) | 8 (4.4) | ||

| Pack-years | ||||

| Never smoker | 75 (41.9) | 85 (47.2) | 1.00 | |

| Below medianc | 18 (10.1) | 37 (20.6) | 0.55 (0.29–1.05) | |

| At or above median | 44 (24.6) | 39 (21.7) | P = 0.061 | 1.26 (0.74–2.16) |

| Missing | 42 (23.5) | 19 (10.6) | ||

| Alcohol consumption habit | ||||

| Never | 36 (20.1) | 32 (17.8) | 1.00 | |

| Ever | 115 (64.3) | 147 (82.7) | P = 0.182 | 0.67 (0.39–1.16) |

| Missing | 28 (15.6) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Alcohol consumption frequency | ||||

| Never | 36 (20.1) | 32 (17.8) | 1.00 | |

| Below mediand | 50 (27.9) | 70 (38.9) | 0.62 (0.34–1.15) | |

| At or above median | 65 (36.3) | 77 (42.8) | P = 0.329 | 0.72 (0.40–1.29) |

| Missing | 28 (15.6) | 1 (0.6) | ||

| Age at menarche | ||||

| <13 | 71 (39.7) | 89 (49.4) | 1.00 | |

| 13+ | 77 (43.0) | 78 (43.3) | P = 0.346 | 1.22 (0.78–1.91) |

| Missing | 31 (17.3) | 13 (7.2) | ||

| Age at first birth | ||||

| <25 | 76 (42.5) | 76 (42.2) | 1.00 | |

| 25+ | 43 (24.0) | 60 (33.3) | 0.69 (0.41–1.16) | |

| Nulliparous | 28 (15.6) | 38 (21.1) | P = 0.356 | 0.74 (0.41–1.34) |

| Missing | 32 (17.9) | 6 (3.3) | ||

| Parity | ||||

| 1–2 children | 69 (38.6) | 74 (41.1) | 1.00 | |

| 3+ | 52 (29.0) | 64 (35.6) | 1.25 (0.69–2.26) | |

| Nulliparous | 28 (15.6) | 38 (21.1) | P = 0.707 | 1.06 (0.57–1.97) |

| Missing | 30 (16.8) | 4 (2.2) | ||

| Age at menopausee | ||||

| <50 | 37 (41.1) | 54 (52.9) | 1.00 | |

| 50+ | 45 (50.0) | 45 (44.1) | P = 0.207 | 1.41 (0.78–2.54) |

| Missing | 8 (8.9) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| HRTe | ||||

| Never | 44 (48.9) | 43 (42.1) | 1.00 | |

| Ever | 44 (48.9) | 58 (56.7) | P = 0.307 | 0.73 (0.41–1.30) |

| Missing | 2 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) | ||

| Multivitamin use | ||||

| Never or occasionally | 67 (37.3) | 60 (33.3) | 1.00 | |

| Regularly | 84 (46.9) | 118 (65.6) | P = 0.048 | 0.63 (0.40–0.98) |

| Missing | 28 (15.6) | 2 (1.1) | ||

| Histological grade | ||||

| I | 18 (10.1) | |||

| II | 51 (28.5) | |||

| III | 108 (60.3) | |||

| AJCC stage | ||||

| I | 115 (64.3) | |||

| II | 57 (31.8) | |||

| III | 7 (3.9) | |||

| Hormone status | ||||

| ER+/PR+ | 111 (62.0) | |||

| ER+/PR− or ER−/PR+ | 23 (12.9) | |||

| ER−/PR− | 41 (22.9) | |||

| Tumor size | ||||

| <1 cm | 138 (77.1) | |||

| 1–2 cm | 38 (21.2) | |||

| 2 cm+ | 3 (1.7) | |||

| Lymph node involvement | ||||

| No | 135 (75.4) | |||

| Yes | 44 (24.6) | |||

| Metastasis | ||||

| No | 179 (100.0) |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; BMI, body mass index; BRCA, breast cancer; HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

P value by Chi-square test.

OR adjusting for age and race.

Median pack-year = 9.7 pack-year.

Median total alcohol consumption frequency = 1.7 per week for alcohol consumption.

Among postmenopausal women.

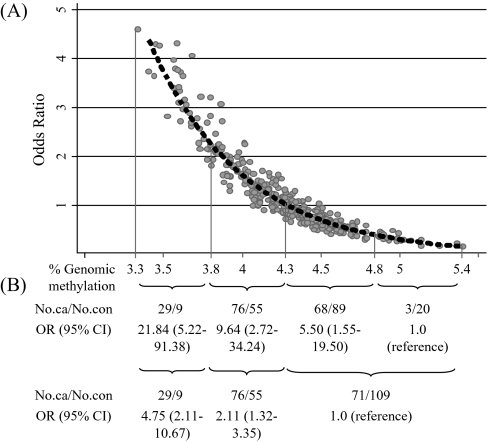

To assess the dose-response relationship of genomic methylation with breast cancer risk, a smoothing spline of the predicted ORs as methylation level increase continuously in the final logistic regression model was drawn using STATA graph. Additionally, global methylation levels were categorized into four groups using cut off values based on the curve; after stratifying by % genomic methylation 4.286 that met OR = 1.0 in the smoothing spline, we cut off midpoint of methylation range in each strata. Midpoint was 3.809 in the lower range of 3.332–4.286 below 4.286 of methylation level and 4.843 in the upper range of 4.286–5.399 above 4.286 of methylation level, respectively. Thus, the range of each category was 3.332–3.809, 3.809–4.286, 4.286–4.843 and 4.843–5.399, respectively.

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 9.0 (Stata corporation, College Station, TX).

Results

Characteristics of cases and age- and race-matched controls are shown in Table I. Missing values for demographic and lifestyle variables were more prevalent in cases compared with controls, but methylation levels were not significantly different between cases with and without missing data for each variable examined (data not shown). Excluding missing values, cases and controls did not significantly differ on any characteristics except multivitamin use, although controls tended to have higher family history of breast cancer, higher education and more frequent use of hormone replacement therapy than cases.

Global methylation levels were analyzed using both 5-mdC and LINE-1 among 37 samples randomly selected from the entire group of study participants as a pilot study. The two markers of global methylation levels in leukocyte DNA were not significantly correlated (r = –0.204, P = 0.232 among all participants). 5-mdC levels in leukocyte DNA were significantly lower in 19 breast cancer cases compared with 18 healthy controls (P = 0.001). In contrast, LINE-1 methylation levels were not significantly different between cases and controls (P = 0.176) (Table II). Based on this preliminary finding, we chose the 5-mdC assay for ascertaining global methylation in the expanded data set.

Table II.

Comparison of global methylation levels in leukocyte DNA measured by two methods (N = 37)

| Median | Cases, n = 19 | Controls, n = 18 | P valuea |

| 5-mdC | 0.001 | ||

| Mean | 3.98 | 4.33 | |

| Median | 3.98 | 4.33 | |

| Interquartile range | 0.45 | 0.27 | |

| LINE-1 | 0.176 | ||

| Mean | 74.70 | 73.90 | |

| Median | 74.50 | 73.50 | |

| Interquartile range | 1.00 | 1.70 |

Assessed by general linear model adjusting for age and race.

As shown in Table III, global methylation levels were not associated with any of the demographic or lifestyle variables examined, except for an inverse association with frequency of alcohol consumption (never, ≤median, >median) in controls (β-coefficient =−0.078, P = 0.031) and in cases and controls combined (β-coefficient = –0.053, P = 0.036), with higher alcohol consumption associated with lower methylation levels. However, frequency of alcohol consumption did not affect the association between global methylation and breast cancer risk.

Table III.

Predictors of global methylation assessed by univariate general linear model (cases = 176 and controls = 173)

| Variables | Among controls |

Among all participants (cases + controls) |

||||

| Mean ± SE of 5-mdC | β | P value | Mean ± SE of 5-mdCa | βb | P valueb | |

| Total | 4.38 ± 0.03 | 4.28 ± 0.02 | ||||

| Age (continuous) | 0.001 | 0.730 | <0.001 | 0.996 | ||

| <Median (55) | 4.41 ± 0.04 | 4.30 ± 0.03 | ||||

| +Median (55) | 4.34 ± 0.04 | −0.068 | 0.208 | 4.26 ± 0.03 | −0.043 | 0.263 |

| Race | ||||||

| Caucasian | 4.38 ± 0.03 | 4.27 ± 0.02 | ||||

| African-American | 4.41 ± 0.08 | −0.032 | 0.781 | 4.31 ± 0.06 | −0.036 | 0.646 |

| Batch (category on date) | −0.001 | 0.776 | 0.004 | 0.248 | ||

| Family history of BRCA | ||||||

| Yes | 4.36 ± 0.03 | 4.27 ± 0.02 | ||||

| No | 4.43 ± 0.06 | 0.069 | 0.300 | 4.29 ± 0.05 | 0.030 | 0.532 |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤high school | 4.35 ± 0.07 | 4.25 ± 0.04 | ||||

| >high school | 4.38 ± 0.03 | 0.033 | 0.624 | 4.28 ± 0.02 | 0.036 | 0.429 |

| BMI (continuous) | 0.001 | 0.790 | 0.002 | 0.496 | ||

| <25 | 4.37 ± 0.04 | 4.26 ± 0.03 | ||||

| 25–29.9 | 4.34 ± 0.04 | 4.26 ± 0.03 | ||||

| 30+ | 4.39 ± 0.06 | 0.012 | 0.730 | 4.28 ± 0.04 | 0.009 | 0.717 |

| Smoking habit | ||||||

| Never | 4.38 ± 0.04 | 4.25 ± 0.03 | ||||

| Ever | 4.37 ± 0.04 | −0.007 | 0.904 | 4.30 ± 0.03 | 0.043 | 0.272 |

| Pack-year (continuous) | 0.001 | 0.534 | <0.001 | 0.766 | ||

| Never smoker | 4.38 ± 0.04 | 4.25 ± 0.03 | ||||

| Below median | 4.37 ± 0.06 | 4.30 ± 0.05 | ||||

| At or above median | 4.37 ± 0.06 | −0.005 | 0.891 | 4.27 ± 0.04 | 0.009 | 0.716 |

| Alcohol consumption habit | ||||||

| Never | 4.45 ± 0.07 | 4.33 ± 0.05 | ||||

| Ever | 4.36 ± 0.03 | −0.087 | 0.209 | 4.26 ± 0.02 | −0.076 | 0.109 |

| Alcohol drinking frequency (continuous) | −0.004 | 0.334 | Less than –0.001 | 0.929 | ||

| Never | 4.45 ± 0.07 | 4.33 ± 0.05 | ||||

| <median | 4.42 ± 0.04 | 4.29 ± 0.03 | ||||

| +median | 4.30 ± 0.04 | −0.078 | 0.031 | 4.23 ± 0.03 | −0.053 | 0.036 |

| Age at menarche | ||||||

| <13 | 4.41 ± 0.04 | 4.30 ± 0.03 | ||||

| +13 | 4.35 ± 0.04 | −0.055 | 0.334 | 4.26 ± 0.03 | −0.036 | 0.375 |

| Age at first birth | ||||||

| <25 | 4.34 ± 0.04 | 4.28 ± 0.03 | ||||

| +25 | 4.36 ± 0.05 | 4.25 ± 0.03 | ||||

| Nulliparous | 4.47 ± 0.06 | 0.062 | 0.080 | 4.31 ± 0.04 | 0.013 | 0.596 |

| Parity (continuous) | −0.004 | 0.884 | −0.002 | 0.916 | ||

| Nulliparous | 4.47 ± 0.06 | 4.27 ± 0.04 | ||||

| 1–2 | 4.36 ± 0.04 | 4.26 ± 0.03 | ||||

| 3+ | 4.34 ± 0.04 | −0.062 | 0.086 | 4.31 ± 0.03 | −0.021 | 0.424 |

| Menopausal status | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 4.38 ± 0.04 | 4.28 ± 0.03 | ||||

| Postmenopausal | 4.37 ± 0.04 | −0.001 | 0.982 | 4.27 ± 0.03 | −0.013 | 0.736 |

| Age at menopause | ||||||

| Premenopausal | 4.38 ± 0.04 | 4.28 ± 0.03 | ||||

| <50 | 4.46 ± 0.05 | 4.31 ± 0.04 | ||||

| +50 | 4.27 ± 0.06 | −0.042 | 0.220 | 4.22 ± 0.04 | −0.026 | 0.271 |

| HRTc | ||||||

| Never | 4.37 ± 0.03 | 4.28 ± 0.02 | ||||

| Ever | 4.38 ± 0.05 | 0.015 | 0.824 | 4.27 ± 0.04 | −0.012 | 0.793 |

| Multivitamin use | ||||||

| Never or occasionally | 4.39 ± 0.05 | 4.31 ± 0.03 | ||||

| Regularly | 4.37 ± 0.03 | −0.004 | 0.892 | 4.25 ± 0.03 | −0.023 | 0.303 |

BMI, body mass index; BRCA, breast cancer; HRT, hormone replacement therapy.

Least square means adjusted for group (case and control) status.

Adjusting for group (case and control) status.

Adjusting for menopausal status.

Global methylation levels in leukocyte DNA were significantly lower in breast cancer cases (4.18 ± 0.34) compared with controls (4.38 ± 0.36; P = 0.001) (Table IV). Compared with women in the highest tertile of methylation, women in the second (OR = 1.49, 95% CI = 0.84–2.65) and lowest tertile (OR = 2.86, 95% CI = 1.65–4.94) had higher risk of breast cancer (P for trend < 0.001). Figure 1A shows the dose-response relationship between global leukocyte DNA methylation levels and breast cancer risk. When groups were recategorized into those above and below methylation level 4.286%, corresponding to an OR = 1 in the smoothing spline, and above and below midpoints of methylation within these two groups, breast cancer risk among those with methylation levels ≤3.809% had an OR = 21.84 (95% CI = 5.22–91.38) compared with those with <4.843% methylation (Figure 1B).

Table IV.

Association between global DNA methylation level classified by the tertiles of the distribution of controls and breast cancer (cases = 176 and controls = 173)

| 5-mdC | Cases, n (%) | Controls, n (%) | OR (95% CI)a | |

| Allb | Mean ± SD | 4.18 ± 0.34 | 4.38 ± 0.36 | <0.001 |

| T3 | 33 (18.8) | 58 (33.5) | 1.0 (reference) | |

| T2 | 49 (27.8) | 58 (33.5) | 1.49 (0.84–2.65) | |

| T1 | 94 (53.4) | 57 (33.0) | 2.86 (1.65–4.94) | |

| P for trend | <0.001 | |||

| Menopausal status | ||||

| Premenopausal | T3 | 11 (19.0) | 21 (30.0) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 18 (31.0) | 26 (36.6) | 1.27 (0.48–3.35) | |

| T1 | 29 (50.0) | 24 (33.8) | 2.21 (0.88–5.57) | |

| P for trend | 0.074 | |||

| Postmenopausal | T3 | 14 (15.9) | 34 (35.1) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 24 (27.3) | 31 (32.0) | 1.88 (0.82–4.31) | |

| T1 | 50 (56.8) | 32 (33.0) | 3.76 (1.73–8.19) | |

| P for trend | 0.001 | |||

| P for interaction | 0.410 | |||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| <55 | T3 | 16 (22.2) | 31 (33.7) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 18 (25.0) | 33 (35.9) | 0.96 (0.40–2.26) | |

| T1 | 38 (52.8) | 28 (30.4) | 2.50 (1.13–5.50) | |

| P for trend | 0.013 | |||

| 55+ | T3 | 17 (16.4) | 27 (33.3) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 31 (29.8) | 25 (30.9) | 1.89 (0.84–4.26) | |

| T1 | 56 (53.9) | 29 (35.8) | 2.81 (1.29–6.11) | |

| P for trend | 0.010 | |||

| P for interaction | 0.947 | |||

| Family history of breast cancer | ||||

| No | T3 | 21 (17.7) | 42 (30.9) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 35 (29.4) | 47 (34.6) | 1.50 (0.75–2.99) | |

| T1 | 63 (52.9) | 47 (34.6) | 2.60 (1.35–4.98) | |

| P for trend | 0.003 | |||

| Yes | T3 | 5 (17.2) | 15 (41.7) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 7 (24.1) | 11 (30.6) | 2.08 (0.50–8.66) | |

| T1 | 17 (58.6) | 10 (27.8) | 5.73 (1.49–21.97) | |

| P for trend | 0.009 | |||

| P for interaction | 0.345 | |||

| BMI (by median) | ||||

| Below 26.5 | T3 | 9 (15.3) | 18 (25.4) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 14 (23.7) | 26 (36.6) | 1.08 (0.36–3.29) | |

| T1 | 36 (61.0) | 27 (38.0) | 2.36 (0.88–6.28) | |

| P for trend | 0.044 | |||

| At or higher 26.5 | T3 | 15 (17.9) | 32 (37.2) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 25 (29.8) | 28 (32.6) | 2.05 (0.88–4.77) | |

| T1 | 44 (52.4) | 26 (30.2) | 3.98 (1.77–8.95) | |

| P for trend | 0.001 | |||

| P for interaction | 0.820 | |||

| Smoking habit | ||||

| Never smoker | T3 | 7 (9.5) | 27 (32.9) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 22 (29.7) | 27 (32.9) | 3.02 (1.09–8.37) | |

| T1 | 45 (60.8) | 28 (34.2) | 6.02 (2.29–15.78) | |

| P for trend | <0.001 | |||

| Ever smoker | T3 | 18 (25.0) | 29 (34.9) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 20 (27.8) | 27 (32.5) | 1.17 (0.50–2.72) | |

| T1 | 34 (47.2) | 27 (32.5) | 1.97 (0.89–4.39) | |

| P for trend | 0.086 | |||

| P for interaction | 0.084 | |||

| Alcohol consumption habit | ||||

| Never drinking alcohol | T3 | 9 (25.0) | 13 (40.6) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 10 (27.8) | 12 (37.5) | 1.35 (0.39–4.63) | |

| T1 | 17 (47.2) | 7 (21.9) | 3.98 (1.11–14.23) | |

| P for trend | 0.033 | |||

| Ever drinking alcohol | T3 | 17 (15.2) | 44 (31.4) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 32 (28.6) | 46 (32.9) | 1.80 (0.87–3.74) | |

| T1 | 63 (56.3) | 50 (35.7) | 3.06 (1.55–6.05) | |

| P for trend | 0.001 | |||

| P for interaction | 0.826 | |||

| Multivitamin use | ||||

| Never or occasional use | T3 | 12 (17.9) | 26 (43.3) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 26 (38.8) | 14 (23.3) | 4.68 (1.75–12.58) | |

| T1 | 29 (43.3) | 20 (33.3) | 4.04 (1.54–10.57) | |

| P for trend | 0.007 | |||

| Regular use | T3 | 14 (17.3) | 31 (27.9) | 1.0 (reference) |

| T2 | 16 (19.8) | 43 (38.7) | 0.76 (0.31–1.83) | |

| T1 | 51 (63.0) | 37 (33.3) | 2.94 (1.34–6.42) | |

| P for trend | 0.001 | |||

| P for interaction | 0.684 |

T1, first tertile; T2, second tertile; T3, third tertile.

Logistic regression model adjusting for age (continuous variable), race (Caucasian, African-American) and batches.

T1 methylation level < 4.25; T2 4.25 ≤ methylation level < 4.50; T3 ≥ 4.50.

Fig. 1.

(A) Predictive risk of breast cancer for genomic methylation of leukocyte after excluding 1% outliers adjusting age, race and batch. (B) Association between categorical methylation level based on the smoothing spline as shown (A) and breast cancer.

When stratified by demographic and lifestyle factors, associations between hypomethylation and increased breast cancer risk were strongest among women with a family history of breast cancer (OR = 5.73, 95% CI = 1.49–21.97 for first tertile versus third tertile, P-interaction = 0.345) and those who never smoked (OR = 6.02, 95% CI = 2.29–15.78 for first tertile versus third tertile, P-interaction = 0.084) (Table IV). Associations did not differ by race, age at diagnosis (median) or alcohol consumption.

Associations with genomic methylation levels did not vary by tumor characteristics, including histological grade, American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM stage, hormone status, tumor size and lymph node involvement in polychotomous model (Table V).

Table V.

Association between global DNA methylation level, classified by tertiles of the distribution of controls and breast cancer stratified by clinicopathologic features

| Groupa | T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

|||

| n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | n | OR (95% CI) | |

| Controls | 58 | 58 | 57 | |||

| Histological grade | ||||||

| I/II | 15 | 1.0 (reference) | 18 | 1.20 (0.55–2.64) | 35 | 2.31 (1.13–4.75) |

| III | 18 | 1.0 (reference) | 30 | 1.67 (0.83–3.34) | 58 | 3.25 (1.69–6.24) |

| AJCC stage | ||||||

| I | 20 | 1.0 (reference) | 28 | 1.43 (0.72–2.85) | 64 | 3.27 (1.73–6.18) |

| II/III | 13 | 1.0 (reference) | 21 | 1.58 (0.72–3.49) | 30 | 2.29 (1.08–4.88) |

| Hormone status | ||||||

| ER+ and PR+ | 21 | 1.0 (reference) | 29 | 1.40 (0.71–2.75) | 59 | 2.84 (1.52–5.32) |

| ER− or PR− | 11 | 1.0 (reference) | 20 | 1.79 (0.78–4.08) | 32 | 2.86 (1.31–6.27) |

| Tumor size | ||||||

| <1 cm | 25 | 1.0 (reference) | 34 | 1.38 (0.73–2.62) | 76 | 3.11 (1.72–5.61) |

| 1 cm+ | 8 | 1.0 (reference) | 15 | 1.81 (0.71–4.65) | 18 | 2.19 (0.87–5.49) |

| Lymph node involvement | ||||||

| No | 24 | 1.0 (reference) | 36 | 1.52 (0.80–2.88) | 72 | 3.01 (1.65–4.50) |

| Yes | 9 | 1.0 (reference) | 13 | 1.42 (0.56–3.62) | 22 | 2.49 (1.04–5.95) |

AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; T1, first tertile; T2, second tertile; T3, third tertile.

ORs by polychotomous logistic regression model adjusting for age (continuous variable), race (Caucasian, African-American) and batches.

T1 methylation level < 4.25; T2 4.25 ≤ methylation level < 4.50; T3 ≥ 4.50.

Discussion

In the pilot study, two measures of global methylation in peripheral blood samples 5-mdC and LINE-1 were not correlated. In the entire study, mean levels of global methylation, measured as the percentage of 5-mdC in leukocyte DNA, were significantly lower in breast cancer cases than in controls and were independently associated with increased breast cancer risk in a dose-dependent manner. Except for frequency of alcohol intake, lifestyle and demographic factors did not predict methylation levels. However, hypomethylation was suggested as a stronger risk factor for breast cancer among women with a family history of breast cancer and among never smokers. Methylation levels were not associated with clinicopathological characteristics of the breast tumors.

As reviewed by Laird (20), there is no consensus, to date, on the best technique for assessing methylation profiles. Repetitive DNA sequences (e.g. LINE-1, Alu, SATα and SAT2) are all comparatively rich in CpG dinucleotides and contain a large portion of total methylcytosine levels in the genome (4,26). Thus, genome-wide changes in DNA methylation are postulated to affect methylation levels in repetitive DNA sequences. A previous study reported that methylation levels in repetitive sequences assessed by methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction techniques using MethylLight were correlated with 5-mdC levels (37); however, there were no associations between methylation levels in LINE-1 measured by pyrosequencing and 5-mdC level in our study. A possible reason for this could be differential sensitivity to detect subtle changes of methylation patterns between the distinct assays used to measure 5-mdC and LINE-1. In addition, LINE-1 methylation status is probably not always predictive of total 5-mdC levels, as the latter measurement reflects the overall contribution of a diverse set of DNA sequence elements including both CpG island and non-CpG island regions.

Consistent with findings from this study, genomic DNA hypomethylation status in leukocyte DNA has recently been associated with risk of colorectal, head and neck and bladder cancer (21–24). Lim et al. (21) reported a dose-dependent inverse association between global 5-mdC levels and risk of asymptomatic colorectal adenoma (OR = 5.8, 95% CI = 2.0–16.6 for lowest tertile versus highest tertile, P for trend = 0.002). In the Spanish Bladder Cancer Study, global methylation levels measured by 5-mdC were also lower among bladder cancer patients than among controls (OR = 2.67, 95% CI = 1.77–4.03). When further stratified by smoking status, current smokers in the lowest methylation quartile had the highest risk of bladder cancer compared with never smokers in the highest methylation quartile (OR = 25.51, 95% CI = 9.61–67.76, P for interaction = 0.06) (22). In another study, hypomethylation of LINE-1 was associated with increased risk of squamous cell cancer of the head and neck (OR = 1.6, 95% CI = 1.1–2.4) (24). In contrast, Wischwendter et al. (38) reported that methylation of Alu-repetitive elements in blood DNA, another surrogate marker correlated with 5-mdC (37), did not differ between breast cancer cases and controls. We also did not observe a difference in methylation levels between breast cancer cases and controls when methylation levels were assessed by LINE-1-repetitive DNA sequences, although associations with 5-mdC levels were evident.

Our findings and others (21–24) indicate that global genomic hypomethylation of leukocyte DNA may be an independent risk factor for multiple cancer types, possibly due to resulting genomic instability. Lower DNA repair capacity in lymphocytes has been associated with increased risk of breast cancer (39,40), and genomic instability measured by micronuclei frequency, levels of DNA single-strand breaks and alkali-labile lesions, sister chromatid exchange and/or spontaneous chromosomal aberrations in peripheral blood cells has been shown to be higher among breast cancer cases compared with healthy controls and women with benign breast disease (25,41–43). Global DNA hypomethylation levels in both normal and cancer cells, however, show the same pattern of hypomethylation with low folate status (44), and methylation patterns appear to vary between different cell types (8). Methylation levels are also probably to differ between cancer DNA and leukocyte DNA; therefore, the use of peripheral leukocyte DNA methylation as a surrogate marker of genomic instability in target tumor tissue should be evaluated in further studies.

There are reports that environmental exposure to nutritional, chemical and physical factors can alter methylation status and produce different phenotypes (45–47). Except for an inverse association between methylation levels and frequency of alcohol consumption, we did not find any demographic or lifestyle predictors of methylation. Association between methylation levels and breast cancer risk, however, did not vary by alcohol consumption in our data set, which is consistent with associations observed in bladder cancer and colorectal adenoma (21,22). Some studies have shown genomic content of 5-mdC to decline with age (45,48,49), although others show global methylation levels in human leukocytes or tumor DNA to be independent of age (22,33,34), consistent with our findings. Because the vast majority of participants in this study were Caucasian, we were unable to analyze associations between DNA methylation and race. Cigarette smoking was not associated with global methylation of leukocyte DNA in agreement with previous studies (22,35,50); however, hypomethylation was suggested as a stronger risk factor for breast cancer risk among non-smokers, which is consistent with findings from Moore et al.‘s study (22). Our finding that associations between methylation levels and breast cancer risk were more profound among women with a family history of breast cancer are also consistent with studies that have noted that genetic factors can affect patterns of methylation. A recent study investigating longitudinal changes in global methylation in healthy individuals found familial clustering of methylation changes (51), suggesting genetic control of maintenance methylation. However, further large studies are needed to confirm the subgroup analysis.

We did not find any associations between global methylation levels and tumor characteristics, consistent with findings in colorectal and bladder cancer patients (21,22). Using breast tissue DNA from breast cancer cases, however, a number of studies (7,8,10,52) have found significant correlations between global hypomethylation and disease stage, tumor size and histological grade. The inconsistencies between the results in normal and tumor tissue probably arise from use of different sources of DNA and/or from differential distributions of clinical characteristics. In our study, most participants had early-stage breast cancer (3.9% of American Joint Committee on Cancer stage III, 1.7% of tumor size ≥2 cm, 24.6% of node involvement and no metastasis as shown in Table I), therefore it may lack the power to assess associations between global methylation levels and clinical features, given the small number of advanced breast cancer cases.

Limitations of our study include unexpected distributions of known breast cancer risk factors among cases and controls, which include higher family history of breast cancer, higher education and more frequent use of hormone replacement therapy among controls. One possible explanation for these observations is differential missing information among cases, which can affect the association with breast cancer as a confounder though we did not find any significant predictor of global methylation level. Another explanation is that DBBR participants were all recruited from within a comprehensive cancer center. Thus, controls within this series included community volunteers (50%), employees of RPCI (33%) and family members or friends of patients (28%). Compared with cases, employee controls were younger and more highly educated but were not significantly different for family history of breast cancer or for reproductive factors. Individuals with a family history of cancer might also be more probably to participate in a ‘cancer study’, which might explain why controls within the DBBR population were more probably to report a family history of breast cancer. The association between methylation levels with breast cancer risk, however, did not differ according to the source of the control (data not shown), and methylation levels did not vary between the different groups of controls (data not shown). Although we assessed potential effect modification, this study had a relatively small sample size for the subgroup analysis and had lack of power to find significant interactions on the association between global methylation and breast cancer risk. We did not assess dietary or genetic factors involved in 1-carbon metabolism as effect modifiers in this study, although inconsistent associations have been reported in human studies (21,22,53,54).

This study showed genomic hypomethylation of leukocyte DNA, as a surrogate of systemic methylation activity, to be associated with increased breast cancer risk, with associations being particularly strong among non-smokers and women with a family history of breast cancer. These findings provide greater understanding of factors that may modify breast cancer risk and could lead to development of a simple non-invasive blood measure of DNA hypomethylation to identify women at high risk for breast cancer.

Funding

Mae Stone Goode Foundation (C.A.); National Cancer Institute (RO1CA11674 to A.R.K.).

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest Statements: None declared.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- DBBR

Databank and Biorepository

- 5-mdC

5-methyldeoxycytosine

- OR

odds ratio

- RPCI

Roswell Park Cancer Institute

References

- 1.Jones PA, et al. The fundamental role of epigenetic events in cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrg816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson AS, et al. DNA hypomethylation and human diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1775:138–162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn BK. Hypomethylation: one side of a larger picture. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2003;983:28–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05960.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrlich M. DNA methylation in cancer: too much, but also too little. Oncogene. 2002;21:5400–5413. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feinberg AP, et al. The epigenetic progenitor origin of human cancer. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2006;7:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrg1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feinberg AP, et al. The history of cancer epigenetics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004;4:143–153. doi: 10.1038/nrc1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soares J, et al. Global DNA hypomethylation in breast carcinoma: correlation with prognostic factors and tumor progression. Cancer. 1999;85:112–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernardino J, et al. DNA hypomethylation in breast cancer: an independent parameter of tumor progression? Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 1997;97:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(96)00385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gama-Sosa MA, et al. The 5-methylcytosine content of DNA from human tumors. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:6883–6894. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.19.6883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson K, et al. DNA hypomethylation is prevalent even in low-grade breast cancers. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2004;3:1225–1231. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.12.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esteller M, et al. DNA methylation patterns in hereditary human cancers mimic sporadic tumorigenesis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001;10:3001–3007. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.26.3001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feinberg AP, et al. Hypomethylation distinguishes genes of some human cancers from their normal counterparts. Nature. 1983;301:89–92. doi: 10.1038/301089a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holliday R, et al. DNA modification mechanisms and gene activity during development. Science. 1975;187:226–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaudet F, et al. Induction of tumors in mice by genomic hypomethylation. Science. 2003;300:489–492. doi: 10.1126/science.1083558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robertson KD. DNA methylation, methyltransferases, and cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:3139–3155. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark SJ, et al. DNA methylation and gene silencing in cancer: which is the guilty party? Oncogene. 2002;21:5380–5387. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karpf AR, et al. Genetic disruption of cytosine DNA methyltransferase enzymes induces chromosomal instability in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8635–8639. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Szyf M, et al. DNA methylation and breast cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;68:1187–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silva JM, et al. Presence of tumor DNA in plasma of breast cancer patients: clinicopathological correlations. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3251–3256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laird PW. The power and the promise of DNA methylation markers. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:253–266. doi: 10.1038/nrc1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim U, et al. Genomic methylation of leukocyte DNA in relation to colorectal adenoma among asymptomatic women. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:47–55. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore LE, et al. Genomic DNA hypomethylation as a biomarker for bladder cancer susceptibility in the Spanish Bladder Cancer Study: a case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:359–366. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pufulete M, et al. Folate status, genomic DNA hypomethylation, and risk of colorectal adenoma and cancer: a case control study. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1240–1248. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00279-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsiung DT, et al. Global DNA methylation level in whole blood as a biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:108–114. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iarmarcovai G, et al. Micronuclei frequency in peripheral blood lymphocytes of cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Mutat. Res. 2008;659:274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoffmann MJ, et al. Causes and consequences of DNA hypomethylation in human cancer. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;83:296–321. doi: 10.1139/o05-036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prak ET, et al. Mobile elements and the human genome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2000;1:134–144. doi: 10.1038/35038572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang AS, et al. A simple method for estimating global DNA methylation using bisulfite PCR of repetitive DNA elements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32 doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambrosone CB, et al. Establishing a cancer center data bank and biorepository for multidisciplinary research. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1575–1577. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Song L, et al. Specific method for the determination of genomic DNA methylation by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:504–510. doi: 10.1021/ac0489420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Colella S, et al. Sensitive and quantitative universal Pyrosequencing methylation analysis of CpG sites. Biotechniques. 2003;35:146–150. doi: 10.2144/03351md01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Woloszynska-Read A, et al. Intertumor and intratumor NY-ESO-1 expression heterogeneity is associated with promoter-specific and global DNA methylation status in ovarian cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:3283–3290. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-5279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ogino S, et al. LINE-1 hypomethylation is inversely associated with microsatellite instability and CpG island methylator phenotype in colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2008;122:2767–2773. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalitchagorn K, et al. Distinctive pattern of LINE-1 methylation level in normal tissues and the association with carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2004;23:8841–8846. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Terry MB, et al. Genomic DNA methylation among women in a multiethnic New York City birth cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2306–2310. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piyathilake CJ, et al. Race- and age-dependent alterations in global methylation of DNA in squamous cell carcinoma of the lung (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:37–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1022573630082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weisenberger DJ, et al. Analysis of repetitive element DNA methylation by MethyLight. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:6823–6836. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Widschwendter M, et al. Epigenotyping in peripheral blood cell DNA and breast cancer risk: a proof of principle study. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2656. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Machella N, et al. Double-strand breaks repair in lymphoblastoid cell lines from sisters discordant for breast cancer from the New York site of the BCFR. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1367–1372. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Someya M, et al. Association of DNA-PK activity and radiation-induced NBS1 foci formation in lymphocytes with clinical malignancy in breast cancer patients. Oncol. Rep. 2007;18:873–878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hussien MMI, et al. Investigation of systemic folate status, impact of alcohol intake and levels of DNA damage in mononuclear cells of breast cancer patients. Br. J. Cancer. 2005;92:1524–1530. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang X, et al. A comparison of folic acid deficiency-induced genomic instability in lymphocytes of breast cancer patients and normal non-cancer controls from a Chinese population in Yunnan. Mutagenesis. 2006;21:41–47. doi: 10.1093/mutage/gei069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roy SK, et al. Spontaneous chromosomal instability in breast cancer families. Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 2000;118:52–56. doi: 10.1016/s0165-4608(99)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pufulete M, et al. Effect of folic acid supplementation on genomic DNA methylation in patients with colorectal adenoma. Gut. 2005;54:648–653. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.054718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fraga M, et al. Epigenetic differences arise during the lifetime of monozygotic twins. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:10604–10609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500398102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dolinoy DC, et al. Maternal genistein alters coat color and protects Avy mouse offspring from obesity by modifying the fetal epigenome. Environ. Health Perspect. 2006;114:567–572. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vucic EA, et al. Epigenetics of cancer progression. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9:215–234. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thaler R, et al. Epigenetic regulation of human buccal mucosa mitochondrial superoxide dismutase gene expression by diet. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;101:743–749. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508047685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Suzuki K, et al. Global DNA demethylation in gastrointestinal cancer is age dependent and precedes genomic damage. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:199–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith IM, et al. DNA global hypomethylation in squamous cell head and neck cancer associated with smoking, alcohol consumption and stage. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;121:1724–1728. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bjornsson HT, et al. Intra-individual change over time in DNA methylation with familial clustering. JAMA. 2008;299:2877–2883. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.24.2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsuda H, et al. Correlation of DNA hypomethylation at pericentromeric heterochromatin regions of chromosomes 16 and 1 with histological features and chromosomal abnormalities of human breast carcinomas. Am. J. Pathol. 2002;161:859–866. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Narayanan S, et al. Associations between two common variants C677T and A1298C in the methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene and measures of folate metabolism and DNA stability (strand breaks, misincorporated uracil, and DNA methylation status) in human lymphocytes in vivo. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13:1436–1443. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rampersaud GC, et al. Genomic DNA methylation decreases in response to moderate folate depletion in elderly women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000;72:998–1003. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.4.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]